Abstract

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent serine/threonine kinase that interacts with β integrins. Here we show that endothelial cell (EC)-specific deletion of ILK in mice confers placental insufficiency with decreased labyrinthine vascularization, yielding no viable offspring. Deletion of ILK in zebra fish using antisense morpholino oligonucleotides results in marked patterning abnormalities of the vasculature and is similarly lethal. To dissect potential mechanisms responsible for these phenotypes, we performed ex vivo deletion of ILK from purified EC of adult mice. We observed downregulation of the active-conformation of β1 integrins with a striking increase in EC apoptosis associated with activation of caspase 9. There was also reduced phosphorylation of the ILK kinase substrate, Akt. However, phenotypic rescue of ILK-deficient EC by wild-type ILK, but not by a constitutively active mutant of Akt, suggests regulation of EC survival by ILK in an Akt-independent manner. Thus, endothelial ILK plays a critical role in vascular development through integrin-matrix interactions and EC survival. These data have important implications for both physiological and pathological angiogenesis.

Endothelial cells form the innermost single-cell-thick lining of the cardiovascular system and are intimately involved in vascular homeostasis and cellular trafficking. Factors that influence the balance between endothelial cell survival and death have a profound impact on a host of biological processes, including angiogenesis and the maintenance of vascular integrity (6, 22, 35). Moreover, endothelial dysfunction without overt cell death may constitute an early step in pathological conditions such as atherosclerosis (18).

Integrins are a family of heterodimeric (αβ) transmembrane cell surface receptors that mediate cell-cell adhesion as well as cell-matrix contacts (4, 5, 14, 24). Integrin-ligand interactions transduce signals that modulate the migration, proliferation, differentiation, and survival of cells. Signals originating from within the cell, in turn, can influence the avidity or affinity of integrins for their extracellular ligands. Recent data from several lines of investigation suggest that integrin-Linked kinase (ILK) is a crucial binding partner of integrins (11, 23, 34). ILK is a highly conserved serine/threonine protein kinase with pleckstrin homology and ankyrin repeat domains. ILK was identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen by virtue of its interaction with the cytoplasmic domain of β1 integrins (23). ILK also interacts with critical actin-binding proteins, such as paxillin, CH-ILKBP, and affixin via its C-terminal kinase domain and with the Lim-domain-only proteins, PINCH1 and -2, via its first ankyrin domain (41). Several in vitro studies have suggested that ILK confers key survival signals via its ability to phosphorylate and activate Akt/protein kinase B (12, 32, 38). ILK also plays a critical structural role in the formation of integrin adhesion complexes. From a functional perspective, overexpression of ILK in epithelial cells confers anchorage-independent cell growth and tumorigenicity in nude mice, and several human tumors, including melanoma, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer, have marked overexpression of ILK (1, 10, 19). ILK has also been implicated in the adhesion of leukocytes (15).

To address more definitively the physiological role of ILK in vivo, investigators have turned to genetic models. Deletion of ILK in Caenorhabditis elegans leads to embryonic demise that resembles the phenotype of β-integrin knockouts (27). Similarly, complete knockout in mice confers peri-implantation lethality, since ILK is critical for epiblast polarization (34). More recent studies have shown that tissue-specific deletion of ILK in chondrocytes leads to abnormalities in bone proliferation and dwarfism (20, 37). For the present studies, we employed both the Cre-lox system with mice to specifically evaluate the role of ILK in endothelial biology and antisense technology with zebra fish to study the effects of global deficiency on vascular development. In vivo and in purified endothelial cells, we found a critical role for ILK in vascular development and in integrin-matrix interactions and cell survival. The effects of ILK in these pathways may have important implications for both endothelial cell homeostasis and vascular pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) with or without Ca2+ and Mg2+, 1 M HEPES, penicillin-streptomycin, nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, l-glutamine, and trypsin were purchased from BioWhittaker, Inc. Fetal bovine serum was obtained from Gibco, and endothelial mitogen was obtained from Biomedical Technologies. Heparin and collagenase type II were purchased from Sigma.

Murine system.

We employed a recently generated mouse strain carrying a LoxP-flanked (floxed) ILK gene (ILKflox/flox) which has been previously described in detail (37, 38). To delete ILK in vivo in endothelial cells, ILKflox/flox mice were bred to transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the direction of the tyrosine kinase Tek (Tie2) promoter/enhancer (Tie2-Cretg/+), which provides expression in endothelial cells during embryogenesis and adulthood (25).

Genotype determination for Tie2-Cre transgene and ILK alleles.

Gene and transgene designations are followed by genotype information in superscript text. Superscript plus and flox indicate wild-type and floxed alleles, respectively. In Tie2-Cre transgenic mice, superscript tg and plus indicate presence and absence (wild type), respectively, of the transgene. DNA was obtained from digested tails of adult mice and from yolk sacs of dissected embryos. Inheritance of the Tie2-Cre transgene was determined by PCR using the following primers: forward, 5′-GGTCGATGCAACGAGTGATGAGGT-3′; reverse, 5′-CAGCATTGCTGTCACTTGGTCGTG-3′. ILK genotype was determined by PCR using two primers, 5′-CCAGGTGGCAGAGGTAAGTA-3′ and 5′-CAAGGAATAAGGTGAGCTTCAGAA-3′, for simultaneous detection of wild-type, floxed, and Cre-recombined alleles. The respective product sizes were 1.9 kb, 2.1 kb, and 230 bp. DNAs were amplified for 35 cycles (94°C for 45s, 55°C for 45s, 72°C for 2 min) in a thermal cycler.

Analysis of embryos.

Timed matings were set up between male Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKwt/flox mice and female mice either homozygous or heterozygous for the ILK-floxed allele. Embryos and placentae were harvested between embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) and E12.5, fixed in paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (2% [vol/vol]) at 4°C for 2 h, and transferred to phosphate-buffered saline. Embryos were photographed, and embryos and placentae were embedded in paraffin, sectioned (6 μm), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Yolk sacs were assessed by whole-mount PECAM immunostaining using a purified anti-CD31 antibody (Pharmingen).

Zebra fish.

All experiments were performed with the Top Longfin zebra fish strain. Embryos obtained from natural spawnings were raised and maintained as described previously (39). Embryos were staged according to morphological criteria (somite number) and by timing in hours postfertilization. Transgenic lines expressing green coral fluorescent protein (GCFP) under the control of the flk-1 promoter [TG (flk1:GCFP)] were used to visualize vasculogenesis and embryonic angiogenesis (9). The cDNA of the zebra fish ortholog of ILK-1 was cloned, and antisense morpholino oligonucleotides were designed against the splice donor sequences of exon 1. Morpholinos (Gene Tools, LLC), received as sterile salt-free lyophilized solids, were resuspended in sterile water to a concentration of 1 mM. For injections, this stock solution was diluted to 120 uM with 1× Daniau's solution [58 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.6 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.5 mM HEPES (pH 7.6)] and injected in a volume of ∼5 nl. The morpholino sequence was 5′-ATGCACTCACCCCTGGTTTAGGTC-3′. Morpholinos were injected into one-cell-stage zebra fish embryos at the yolk/cytoplasm interface, using a Narishige micromanipulator connected to a pressure injector (Eppendorf).

Isolation and culture of primary murine endothelial cells.

Primary endothelial cells were isolated and purified from the lungs of ILKflox/flox mice and wild-type littermates as previously described (16, 17). This protocol employed a two-step magnetic bead (Dynabead M-450, Dynal Corp.) purification with rat anti-mouse ICAM-2 and PECAM-1 antibody (Pharmingen). Cells were typically >92% pure as assessed by flow cytometry for CD31 (data not shown).

Recombinant adenoviruses and endothelial cell transduction.

The adenoviruses carrying wild-type ILK (15), as well as the adenovirus control (AdGFP) (30), constitutively active Akt (Admyr-Akt) (30), and Cre recombinase (AdCre) (2) constructs have all been described previously in detail. Endothelial cells grown to ∼70% confluence on 0.1% gelatin-coated six-well plates were transfected with the indicated adenovirus construct at various concentrations in 500 μl of complete medium for 4 h at 37°C, and the volume was then replaced with 2 ml of fresh complete medium. Transfections were carried out for a total of 96 h. For rescue experiments, endothelial cells were transfected with various adenovirus constructs for 4 h prior to cotransfection with AdGFP or AdCre as described above.

Antibodies.

Studies employed antibodies to ILK (Upstate Biotechnology), Cre (Novagen), phospho-Akt (S473), and total Akt (both from Cell Signaling), phospho-Akt (T308) (Biomol), phospho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (Cell Signaling), phospho-glycogen synthase kinase 3 (phospho-GSK-3) and total GSK-3 (both from Cell Signaling), phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (Erk 1/2) (Cell Signaling), total Erk 1/2 (Santa Cruz), and beta actin (Abcam). For flow cytometry analysis, we used antibodies to CD31 (Pharmingen), active β-1 integrin (clone 9EG7; Pharmingen), total β1 integrin (anti-CD29; Pharmingen), total β3 integrin (anti-CD61; Pharmingen), and the corresponding isotype-matched controls (all from Pharmingen). For immunostaining we employed F-actin phalloidin (Molecular Probes) and antivinculin (Sigma) in conjunction with an Alexa-conjugated secondary antibody.

Western blotting and Akt kinase assay.

Western analysis employing the indicated antibody was performed as previously described in detail (15, 30). Akt kinase activity was assessed using a nonradioactive assay kit (no. 9840; Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody specific for the sites phosphorylated by Akt on the substrate peptide (anti-phospho-GSK-3 S21/S9).

Apoptosis assays.

Endothelial cell apoptosis was assessed by cell death detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measuring cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragmentation (kit no. 1544675; Roche), by Western blot analysis for caspases 3, 8, and 9 (Cell Signaling), and by Hoechst staining (33342; Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Assays were performed in the presence of serum and mitogens as described previously (16, 17).

Flow-cytometric analysis.

Endothelial cells were harvested by gentle scraping in their culture media and washed once with assay buffer (1× DPBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+-1% fetal bovine serum, 400 g, 5 min, room temperature). Cells were resuspended in 100 μl of assay buffer and blocked with serum (1:10) for 5 min at room temperature. For analysis of the β1 integrin activation state, cells were equilibrated with the indicated antibody for 5 min in the incubator (37°C, 5% CO2), followed by a 5-min period with or without manganese stimulation (Mn at 2 mM). Reactions were stopped by addition of 3 ml of ice-cold assay buffer followed by a second wash in the same volume. Cells were then stained with the indicated primary and secondary antibodies in blocking buffer and fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, and flow cytometry was performed using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur set to detect fluorescence, forward scatter, and side scatter.

Confocal microscopy.

Endothelial cells were washed once with 1× DPBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in DPBS for 10 min at room temperature. Monolayers were permeabilized for 5 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature and blocked for 30 min at 37°C with blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin in DPBS). Following incubation with the indicated primary and secondary antibodies, cells were washed with DPBS and examined with a Nikon TE300 inverted fluorescence microscope fitted with a Bio-Rad 1024 confocal laser.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Statistical comparison of means was performed by using the two-tailed unpaired Student t test. The null hypothesis was considered to be rejected at P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

We first bred recently generated ILKflox/flox mice (37, 38) to transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the direction of the tyrosine kinase Tie2 promoter/enhancer, which provides expression in endothelial cells during embryogenesis and adulthood (25). Matings of Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKflox/+ males to ILKflox/flox females generated 56 Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKflox/+ progeny, 36 Tie2-Cre+/+:ILKflox/flox progeny, and 40 Tie2-Cre+/+:ILKflox/+ progeny. At birth, approximately 25% of these pups were expected to show ILK deleted in an endothelium-specific manner (Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKflox/flox). However, to date we have obtained no such progeny among 132 viable offspring, suggesting that endothelial ILK deficiency results in embryonic lethality (P < 0.0001 by χ2 analysis).

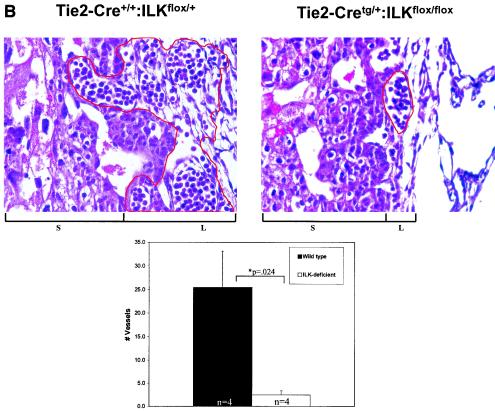

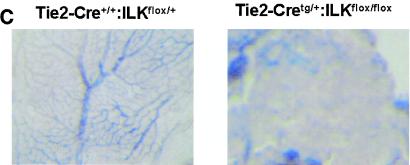

Subsequent analysis revealed that viable Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKflox/flox embryos were present at midgestation but displayed marked overall growth retardation by E9.5 (Fig. 1A), which coincides temporally with expected Tie2 promoter/enhancer-driven Cre expression in the embryo (13). Because vascularization of the placental labyrinth is a critical determinant of continued fetal development at this stage, we postulated that gross retardation resulted from failure of chorioallantoic placental circulation (21, 33). Examination of wild-type E9.5 placentae revealed chorioallantoic apposition, well-formed umbilical vessels, and the presence of major placental tissue layers (decidua, trophoblast giant cells, spongiotrophoblast, and chorionic epithelium). However, placentae of Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKflox/flox mice had much smaller chorioallantoic plates and greatly diminished labyrinthine vasculature, with a more than sevenfold diminution of organized endothelial-cell-lined vascular networks (Fig. 1B). We did not observe the normally robust allantoic vessel extension into the chorion or significant branching morphogenesis of chorionic epithelium in placentae of Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKflox/flox mice. Taken together, these observations indicated that ILK deficiency in fetal endothelium leads to ineffective allantoic vessel-chorion interaction, failed branching morphogenesis of chorionic epithelium, and placental labyrinth insufficiency. Similarly, there was a striking failure of yolk sac vascularization evident by E10.5, in which the fine network of branching capillaries was entirely absent (Fig. 1C), resulting in extreme friability of tissues. Finally, there appeared to be pleiotropic effects of ILK deficiency in the embryos themselves. The major axial vasculature, including the dorsal aortae, cardinal veins, and their branches, was abnormal. Vessels were smaller and fewer in number seen in the context of disorganized surrounding tissue (Fig. 1D). Notable was the incomplete closure of the neural tube in multiple ILK-deficient mutants; however, whether this represents a primary defect in the embryo or occurs as a consequence of the placental/yolk sac abnormalities remains to be defined. Together these abnormalities resulted in embryonic demise and resorption by approximately E11.5 to 12.5.

FIG. 1.

Endothelium-specific deletion of ILK in mice. Embryos, placentae, and yolk sac were harvested at E9.5 to E10.5. (A) Images of whole embryos of Tie2-Cre+/+:ILKflox/+ and Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKflox/flox genotypes. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained section from placentae of Tie2-Cre+/+:ILKflox/+ and Tie2-Cretg/+:ILKflox/flox embryos. Chorionic/labyrinthine vessels (indicated by red outline), filled with nucleated red cells generated in the embryos, were counted from control (15.3 ± 7.6) and mutant (2.5 ± 0.0.87) placentae (n = 4; P = 0.024), below. S, spongiotrophoblast; L, labyrinth. (C) Whole-mount stained yolk sacs, using anti-PECAM antibody. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained embryo sections from head region. Vessels are indicated with asterisks.

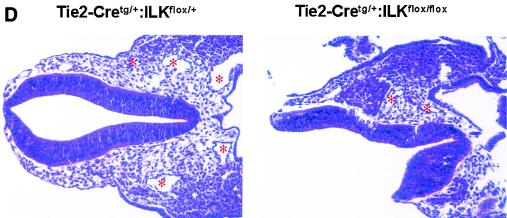

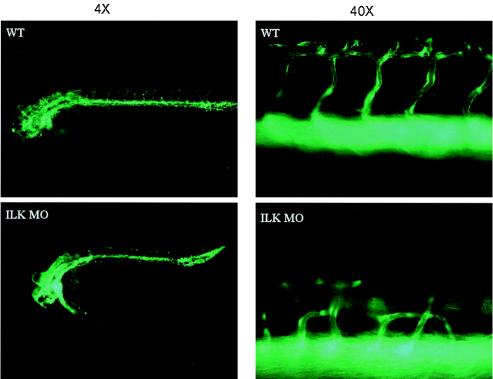

To complement the analysis in the mice and circumvent placental confounders, we turned to parallel studies in the zebra fish model, employing antisense morpholino oligonucleotides. In ILK knockdown fish (>95% decrease in mRNA compared to the wild type; data not shown), we saw striking evidence of disordered patterning of those trunk vessels that are formed by angiogenesis. This patterning was investigated using the morpholino in fish transgenic for GCFP under the direction of the flk-1 promoter (Fig. 2) (9). The normal network of intersegmental vessels was absent for a variable number of thoracic segments, usually extending caudally from the second or third somite. In segments flanking the areas of complete vessel loss there were regions where intersegmental vessels from the dorsal aorta fused with the intersegmental vessels from the adjacent intersomitic boundary, rather than extending to the dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessel. These aberrant vessels consistently joined their neighbors at the next intersomitic boundary at one of two locations: at the level of the parachordal vessels (lateral to the horizontal myoseptum) or at the level of the vertebral arteries (between the notochord and the neural tube).

FIG. 2.

Knockdown of ILK in zebra fish. Morpholinos were injected into one-cell-stage zebra fish embryos as described in Materials and Methods. Patterning was investigated by using the morpholino in fish transgenic for GCFP under the direction of the flk-1 promoter. Fluorescence microscopy reveals loss of the normal regular network of intersegmental and parachordal vessels for a variable number of thoracic segments, usually extending caudally from the second or third somite. Other regions of the intersegmental vasculature exhibited patterning defects as described in the text. WT, wild type.

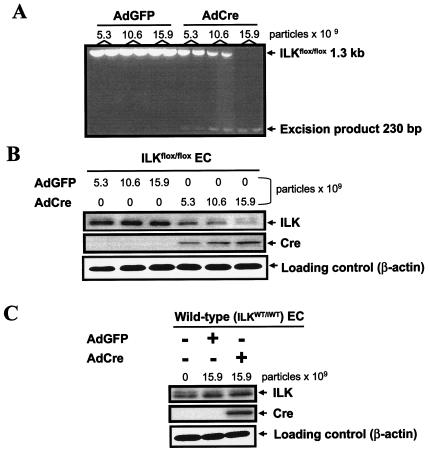

To dissect the mechanisms that might be contributing to lethality in the knockout animals, we isolated primary endothelial cells from homozygous ILKflox/flox mice. We transduced the purified endothelial cells from ILKflox/flox mice with a recombinant adenovirus encoding Cre recombinase (2). As seen in Fig. 3, AdCre transduction conferred a dose-dependent increase in Cre protein expression in this system (Fig. 3B). Consequently, we observed a dose-dependent excision of the ILK gene (Fig. 3A) with marked diminution of ILK protein expression 4 days after transfection (Fig. 3B). As expected, overexpression of Cre recombinase in endothelial cells isolated from wild-type mice did not induce any changes in ILK protein levels (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Effects of Cre recombinase on ILK expression in endothelial cells. (A) Endothelial cells were isolated from ILKflox/flox mice, transfected with adenoviruses encoding either green fluorescent protein (AdGFP) or Cre recombinase (AdCre) at the indicated doses, and cultured for 96 h. PCR for the ILK gene and presence of excision product were assessed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Protein expression of ILK and Cre was assessed by Western blot analysis in the same endothelial cells. (C) Western analysis was performed on transduced endothelial cells from wild-type littermates. Representative data from one of four independent experiments are shown.

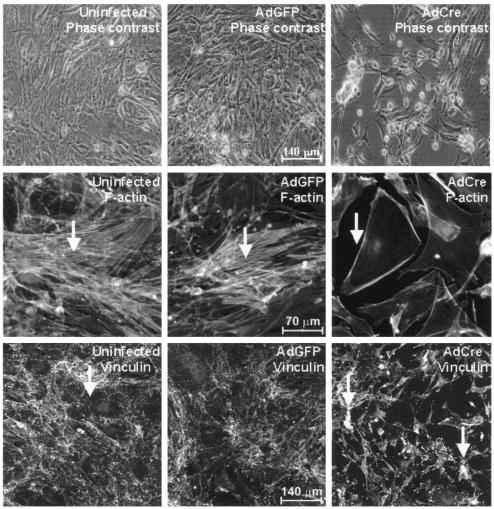

Deletion of ILK induced dramatic changes in purified adult endothelial cells (Fig. 4). Phase-contrast microscopy revealed that many ILK-deficient endothelial cells rounded up and detached from the previously intact endothelial cell monolayer. Since data for other systems suggest a role for ILK in stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton (40, 41), we then analyzed endothelial cells lacking ILK for changes in focal adhesion formation using confocal microscopy. In staining for F-actin (phalloidin), we saw a dramatic reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton with loss of stress fibers in the intracellular cytoplasmic area and marked peripheral accentuation (Fig. 4, middle panel). In staining for the focal adhesion protein vinculin, we also observed redistribution to the cellular periphery and the formation of coarse granules consistent with the disruption of focal adhesions (Fig. 4, lower panel).

FIG. 4.

Microscopic analysis of ILK-deficient endothelial cells. Endothelial cells were purified from ILKflox/flox mice and transduced with either AdGFP or AdCre as described above or left uninfected. Phase-contrast microscopy shows rounded shape and subsequent detachment of ILK-deficient cells. F-actin phalloidin staining (middle panel, arrows) demonstrates typical stress fibers in untransduced and green fluorescent protein-transduced endothelial cells, with marked loss and peripheral accentuation in ILK deletion cells. Antivinculin staining (lower panel, arrows) shows atypical coarse granules, suggestive of disrupted focal adhesions in ILK-deficient endothelial cells. Results shown are representative of one of three independent experiments.

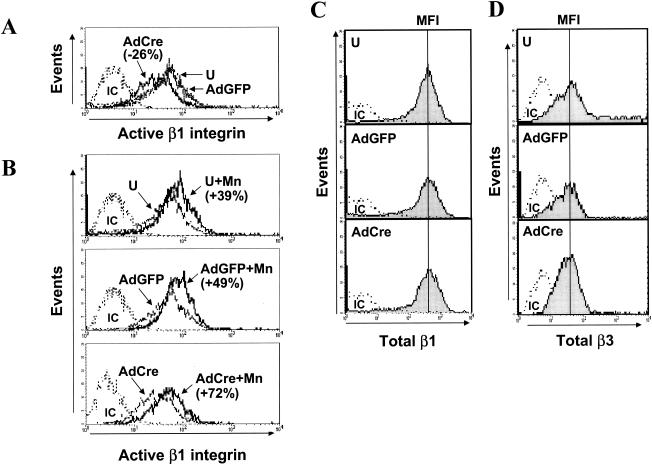

We then explored the mechanisms that might be contributing to abnormal cell-matrix interactions in the ILK-deficient endothelium. Since ILK associates with β integrins, we analyzed β1 integrins using an antibody that reliably detects the ligand-bound conformation of β1 integrins that correlates with integrin activation (3, 26). We consistently found a significant downregulation of the active conformation of β1 integrins in ILK-deficient endothelial cells, compared to uninfected and control AdGFP-transduced cells (Fig. 5A). Treatment of endothelial cells with manganese (Mn), which locks integrins in high-affinity states, triggered significant increases in the β1 integrin activation state in untransduced, AdGFP-transduced, and AdCre-transduced endothelial cells. Thus, the integrins in ILK-deficient cells could still be activated (Fig. 5B). Importantly, our analysis excluded nonviable cells, and total levels of surface β1 and β3 integrins were unchanged after loss of ILK (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG. 5.

Flow-cytometric analysis of β-integrin expression and activity in ILK-deficient endothelial cells. ILKflox/flox endothelial cells were either left uninfected (U) or transduced with AdGFP or AdCre. Flow-cytometric analysis was performed by using an antibody specific for the active conformation of β1 integrins before (A) and after (B) manganese stimulation (Mn, 2 mM, 5 min, 37°C). We observed a 26% decrease in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in AdCre-transduced, as opposed to uninfected or AdGFP-transduced, endothelial cells. Addition of Mn enhanced β1-integrin activation by 39% in uninfected endothelial cells, 49% in AdGFP-transduced endothelial cells, and 72% in AdCre-transduced endothelial cells. Surface expression of total β1 and β3 integrins as determined by flow cytometric analysis was unchanged (C and D, respectively). Analysis was limited to the viable cell population as determined by propidium iodide staining. Representative data from one of five independent experiments are shown.

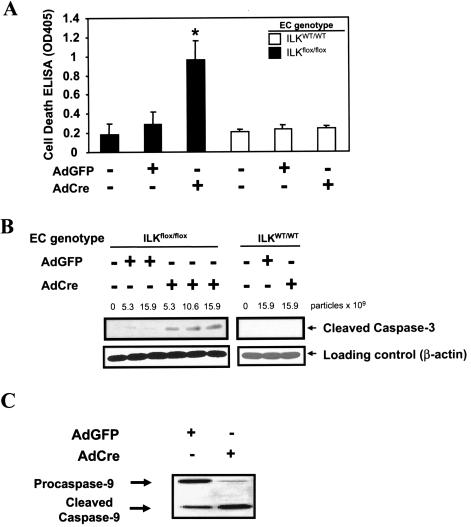

We next analyzed apoptosis of ILK-deficient endothelial cells using multiple independent methods. Using a cell death ELISA assaying for cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragmentation, we found a ∼4-fold increase of DNA fragmentation in endothelial cells lacking ILK, compared to results with uninfected and control AdGFP-transduced cells (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, we saw a dose-dependent increase in the cleavage product of caspase 3 using Western blot analysis (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, analysis upstream of caspase 3 revealed that cell death was associated with activation of caspase 9 (Fig. 6C), the apical caspase in mitochondrial apoptosis, but not caspase 8 (not shown), the proximal caspase in death receptor-mediated apoptosis. Multiple analyses of ILK-deficient cells by using Hoechst, annexin V, and propidium iodide staining reveal that approximately 16 to 25% are apoptotic 96 h after transduction with AdCre. This range is comparable to what we observe following 6 h of cycloheximide treatment (40 μcg/ml, 6 h, 37°C), a commonly used trigger of cell death (data not shown). Importantly, transfection of wild-type endothelial cells with AdCre did not lead to any changes in cell survival (Fig. 6A and B) or to structural changes (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Effects of targeted deletion of ILK on endothelial apoptosis. As described above, endothelial cells were transduced with AdGFP or AdCre or left uninfected. (A) Programmed cell death in endothelial cells was assessed after 96 h by specific cell death detection ELISA (n = 5; *, P < 0.001 versus uninfected and AdGFP-transduced cells). Endothelial cell apoptosis was quantified by Western blot analysis probing for cleaved caspase 3 (B) and caspase 9 (C) (representative data from six independent experiments are shown).

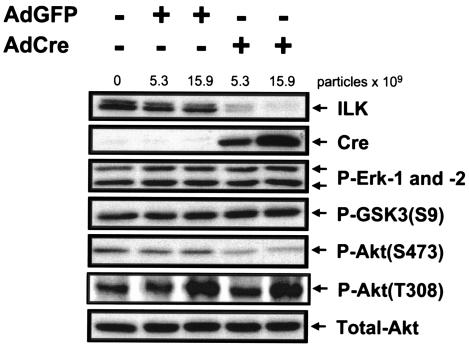

In vitro, ILK can serve as a membrane-proximal upstream modulator of signaling molecules involved in cell survival regulation, such as Akt and GSK-3 (12). Therefore, we examined whether targeted deletion of ILK in endothelial cells impacts downstream signaling pathways implicated in cell survival, as seen in Fig. 7. Using Western blot analysis, we found that the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (as assessed by Erk 1/2 phosphorylation) and GSK-3 signaling [as assessed by GSK-3β(S9) phosphorylation] were unchanged in ILK-deficient endothelial cells. C-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, focal adhesion kinase, and Rac 1 activity were similarly unaffected (data not shown). In contrast, we observed a reproducible decrease in phosphorylation of Akt on the activating phosphorylation site, Ser 473, which has been shown to be phosphorylated by ILK. Phosphorylation of Thr 308 of Akt, a residue which is not a reported target of ILK, was unaltered by ILK excision.

FIG. 7.

Effects of targeted deletion of ILK in endothelial cells on downstream signaling pathways. Endothelial cells were purified from homozygous ILKflox/flox mice and transduced with AdGFP or AdCre or left uninfected. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting, using the indicated primary antibodies. Representative data from one of seven independent experiments are shown.

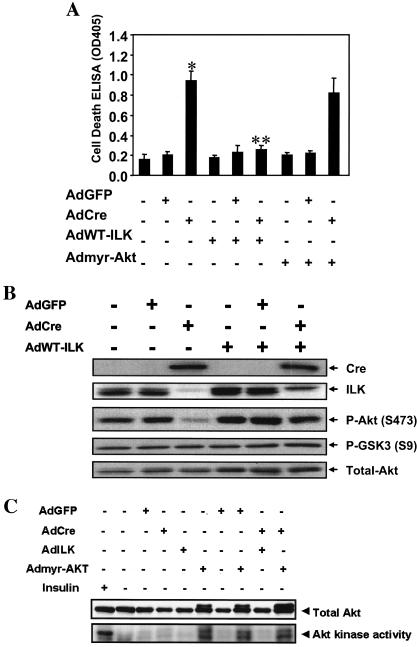

We then examined whether it was possible to rescue ILK-deficient endothelial cells from increased apoptosis by cotransfection with adenovirus constructs encoding the wild-type ILK molecule (AdWT-ILK) (15) and a constitutively active Akt construct (Admyr-Akt) (30). As seen in Fig. 8 (top), cotransfection of AdCre-transduced ILKflox/flox endothelial cells with AdWT-ILK reversed the phenotype and reduced apoptosis back to baseline levels seen in uninfected and control AdGFP-transduced cells. This was accompanied by restoration of phosphorylation on Ser 473 of Akt (Fig. 8, middle). However, cotransfection with an adenovirus encoding a constitutively active Akt molecule (Admyr-Akt) markedly enhanced kinase activity in the endothelial cells (Fig. 8, bottom) but was not sufficient to overcome increased endothelial cell death from lack of ILK. Thus, our data suggest that while there may be alterations in Akt signaling upon deletion of ILK, there are clearly Akt-independent pathways, likely involving ILK interactions with integrins and/or cytoskeletal constituents, that are critical for endothelial cell survival.

FIG. 8.

Rescue of enhanced endothelial cell death after targeted deletion of ILK. ILK-deficient endothelial cells were generated using the ILKflox/flox mice, and cotransfected with a constitutively active form of Akt (Admyr-Akt) or wild-type ILK (AdWT-ILK) as detailed in the Methods. (A) Cell death detection ELISA was used to assess the rate of endothelial cell apoptosis (n = 3; *, P < 0.001 versus uninfected and AdGFP-transduced cells; **, P < 0.001 versus AdCre-transduced cells). (B) Western blot analysis was performed to quantify effects of cotransfecting ILK-deficient endothelial cells with AdWT-ILK on ILK expression and downstream signaling. (C) Western blot analysis and Akt kinase assays were performed to confirm expression of active myristoylated Akt after viral transduction. Representative data from one of five independent experiments are shown.

DISCUSSION

Our in vitro and in vivo genetic studies extend prior investigations of ILK. The integrins αvβ3, αvβ5, and α5β1 are all important regulators of endothelial cell function and survival (4, 5, 14, 24). ILK was originally described for its ability to bind the carboxyl tail of β1 and β3 integrins (23). Our studies, using an available murine integrin activation epitope reagent, show that the activation state of β1 integrins was consistently downregulated in ILK-deficient cells. Our working hypothesis is that loss of endothelial cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix leads to the induction of apoptosis specifically through activation of caspase 9. Recently, investigators have also described a process known as “integrin-mediated death” in which unligated integrins promote apoptosis through membrane recruitment of caspases (7). ILK might play a role in such a process as well, though our findings would suggest involvement of mitochochondrial or stress-induced pathways. Importantly, angiogenesis inhibitors, such as endostatin and tumstatin, have been shown to function by inhibiting integrin function and signaling (28, 29). Assessment of the effects of endothelium-specific ILK deletion in adult mice in vivo, particularly in the context of tumor angiogenesis, will likely be a fruitful avenue for in vestigation. Indeed, recent studies employing a biochemical inhibitor of ILK activity show inhibition of prostate tumor angiogenesis and suppression of tumor growth (36).

As noted above, endothelial cells lacking ILK had marked disruption of stress fibers and accumulated F-actin aggregates at the plasma membrane. Focal adhesions were also perturbed, as evidenced by abnormal vinculin staining. These cytoskeletal abnormalities we observed could have further hindered β1 integrin activation by diminishing integrin clustering and avidity. ILK may play a critical role in actin organization via its interactions with α- and β-parvin, which are members of a new family of actin binding proteins which have been shown to be important in the formation of focal adhesion and stress fibers in in vitro systems (31). ILK can also bind paxillin, which interacts with the focal adhesion protein vinculin. More recently, ILK has been shown to bind the Pinch 1 and 2 proteins (40), which in turn interact with Nck2, a SH2/SH3-containing adapter protein. Nck2 is present at cell adhesion sites and interacts with critical cytoskeleton-related signaling molecules including Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein and Pak (p21-activated serine/threonine kinase). Future studies must determine which of these ILK interactions are functionally relevant in terms of actin stability and focal adhesion formation specifically in endothelial cells.

Our studies with endothelium have also revealed alterations in phosphorylation of Akt on the activating phosphorylation site, Ser 473, but not in the basal phosphorylation state of GSK-3, Erk 1/2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, or focal adhesion kinase. However, apoptosis was not rescued by a constitutive active Akt construct. It must be noted that other studies have shown abnormal Akt signaling in models of ILK deficiency that lead to direct effects on cell survival (37, 38). Undoubtedly, the conflicting results from these various studies reflect cell-specific ILK function in the face of diverse stimuli. Thus, conditional ILK deletion can now be employed to parse out ILK signaling in specific tissues and in specific physiological contexts. How abnormalities in integrin signaling independent of Akt signaling lead to mitochondrial or stress-induced apoptosis remains a subject for future studies.

Data from several groups, including our own, suggest that ILK may also be important in cell spreading and movement (8, 15, 42). Thus, abnormal endothelial chemotaxis may have also contributed to the vascular abnormalities we noted in intact organisms. The marked apoptosis we noted in vitro may have been abrogated somewhat in vivo by other prosurvival signals, and our data do not preclude multiple roles of ILK in endothelial cell biology. Interestingly, the patterning defects we observed in the developing zebra fish were restricted to specific regions of the vasculature, suggesting that heterogeneous mechanisms may regulate vascular development, perhaps presaging adult vessel heterogeneities. Variability of vessel abnormalities from ILK deletion was also observed in the mice. Such differential effects might reflect heterogeneity in the requirements for and consequences of endothelial integrin signaling in different vascular beds and may be confirmed in adults by temporally regulated, endothelium-restricted gene inactivation.

In summary, our genetic studies with two vertebrate organisms demonstrate a role for ILK in integrin-matrix interactions and endothelial cell survival. These pleiotropic effects clearly contribute in critical ways to endothelial cell and vascular development and may have important implications as well for vascular pathology.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the NIH to C.A.M., T.F., D.S.M., A.R., and R.E.G. E.B.F. is a Feodor Lynen Research Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. S.D. is supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute of Canada and Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, N., C. Riley, K. Oliva, E. Stutt, G. E. Rice, and M. A. Quinn. 2003. Integrin-linked kinase expression increases with ovarian tumour grade and is sustained by peritoneal tumour fluid. J. Pathol. 201:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anton, M., and F. L. Graham. 1995. Site-specific recombination mediated by an adenovirus vector expressing the Cre recombinase protein: a molecular switch for control of gene expression. J. Virol. 69:4600-4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazzoni, G., D. T. Shih, C. A. Buck, and M. E. Hemler. 1995. Monoclonal antibody 9EG7 defines a novel beta 1 integrin epitope induced by soluble ligand and manganese, but inhibited by calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 270:25570-25577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks, P. C., R. A. Clark, and D. A. Cheresh. 1994. Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis. Science 264:569-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks, P. C., A. M. Montgomery, M. Rosenfeld, R. A. Reisfeld, T. Hu, G. Klier, and D. A. Cheresh. 1994. Integrin alpha v beta 3 antagonists promote tumor regression by inducing apoptosis of angiogenic blood vessels. Cell 79:1157-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chavakis, E., and S. Dimmeler. 2002. Regulation of endothelial cell survival and apoptosis during angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22:887-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheresh, D. A., and D. G. Stupack. 2002. Integrin-mediated death: an explanation of the integrin-knockout phenotype? Nat. Med. 8:193-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chun, S. J., M. N. Rasband, R. L. Sidman, A. A. Habib, and T. Vartanian. 2003. Integrin-linked kinase is required for laminin-2-induced oligodendrocyte cell spreading and CNS myelination. J. Cell Biol. 163:397-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross, L. M., M. A. Cook, S. Lin, J. N. Chen, and A. L. Rubinstein. 2003. Rapid analysis of angiogenesis drugs in a live fluorescent zebrafish assay. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23:911-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai, D. L., N. Makretsov, E. I. Campos, C. Huang, Y. Zhou, D. Huntsman, M. Martinka, and G. Li. 2003. Increased expression of integrin-linked kinase is correlated with melanoma progression and poor patient survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 9:4409-4414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dedhar, S. 2000. Cell-substrate interactions and signaling through ILK. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delcommenne, M., C. Tan, V. Gray, L. Rue, J. Woodgett, and S. Dedhar. 1998. Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/AKT by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11211-11216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake, C. J., and P. A. Fleming. 2000. Vasculogenesis in the day 6.5 to 9.5 mouse embryo. Blood 95:1671-1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedlander, M., P. C. Brooks, R. W. Shaffer, C. M. Kincaid, J. A. Varner, and D. A. Cheresh. 1995. Definition of two angiogenic pathways by distinct alpha v integrins. Science 270:1500-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedrich, E. B., S. Sinha, L. Li, S. Dedhar, T. Force, A. Rosenzweig, and R. E. Gerszten. 2002. Role of integrin-linked kinase in leukocyte recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 277:16371-16375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerritsen, M. E., C. P. Shen, W. J. Atkinson, R. C. Padgett, M. A. Gimbrone, Jr., and D. S. Milstone. 1996. Microvascular endothelial cells from E-selectin-deficient mice form tubes in vitro. Lab. Investig. 75:175-184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerritsen, M. E., C. P. Shen, M. C. McHugh, W. J. Atkinson, J. M. Kiely, D. S. Milstone, F. W. Luscinskas, and M. A. Gimbrone, Jr. 1995. Activation-dependent isolation and culture of murine pulmonary microvascular endothelium. Microcirculation 2:151-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gimbrone, M. A., Jr. 1999. Endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic forces, and atherosclerosis. Thromb. Haemostasis 82:722-726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graff, J. R., J. A. Deddens, B. W. Konicek, B. M. Colligan, B. M. Hurst, H. W. Carter, and J. H. Carter. 2001. Integrin-linked kinase expression increases with prostate tumor grade. Clin. Cancer Res. 7:1987-1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grashoff, C., A. Aszodi, T. Sakai, E. B. Hunziker, and R. Fassler. 2003. Integrin-linked kinase regulates chondrocyte shape and proliferation. EMBO Rep. 4:432-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurtner, G. C., V. Davis, H. Li, M. J. McCoy, A. Sharpe, and M. I. Cybulsky. 1995. Targeted disruption of the murine VCAM1 gene: essential role of VCAM-1 in chorioallantoic fusion and placentation. Genes Dev. 9:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan, D., and J. Folkman. 1996. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 86:353-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannigan, G. E., C. Leung-Hagesteijn, L. Fitz-Gibbon, M. G. Coppolino, G. Radeva, J. Filmus, J. C. Bell, and S. Dedhar. 1996. Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new beta 1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature 379:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hynes, R. O. 2002. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110:673-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koni, P. A., S. K. Joshi, U. A. Temann, D. Olson, L. Burkly, and R. A. Flavell. 2001. Conditional vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 deletion in mice: impaired lymphocyte migration to bone marrow. J. Exp. Med. 193:741-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenter, M., H. Uhlig, A. Hamann, P. Jeno, B. Imhof, and D. Vestweber. 1993. A monoclonal antibody against an activation epitope on mouse integrin chain beta 1 blocks adhesion of lymphocytes to the endothelial integrin alpha 6 beta 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9051-9055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackinnon, A. C., H. Qadota, K. R. Norman, D. G. Moerman, and B. D. Williams. 2002. C. elegans PAT-4/ILK functions as an adaptor protein within integrin adhesion complexes. Curr. Biol. 12:787-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeshima, Y., M. Manfredi, C. Reimer, K. A. Holthaus, H. Hopfer, B. R. Chandamuri, S. Kharbanda, and R. Kalluri. 2001. Identification of the anti-angiogenic site within vascular basement membrane-derived tumstatin. J. Biol. Chem. 276:15240-15248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeshima, Y., A. Sudhakar, J. C. Lively, K. Ueki, S. Kharbanda, C. R. Kahn, N. Sonenberg, R. O. Hynes, and R. Kalluri. 2002. Tumstatin, an endothelial cell-specific inhibitor of protein synthesis. Science 295:140-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsui, T., L. Li, F. del Monte, Y. Fukui, T. Franke, R. Hajjar, and A. Rosenzweig. 1999. Adenoviral gene transfer of activated PI 3-kinase and Akt inhibits apoptosis of hypoxic cardiomyocytes in vitro. Circulation 100:2373-2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikolopoulos, S. N., and C. E. Turner. 2000. Actopaxin, a new focal adhesion protein that binds paxillin LD motifs and actin and regulates cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 151:1435-1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Persad, S., S. Attwell, V. Gray, M. Delcommenne, A. Troussard, J. Sanghera, and S. Dedhar. 2000. Inhibition of integrin-linked kinase (ILK) suppresses activation of protein kinase B/Akt and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of PTEN-mutant prostate cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3207-3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossant, J., and J. C. Cross. 2001. Placental development: lessons from mouse mutants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2:538-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakai, T., S. Li, D. Docheva, C. Grashoff, K. Sakai, G. Kostka, A. Braun, A. Pfeifer, P. D. Yurchenco, and R. Fassler. 2003. Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is required for polarizing the epiblast, cell adhesion, and controlling actin accumulation. Genes Dev. 17:926-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stupack, D. G., and D. A. Cheresh. 2002. Get a ligand, get a life: integrins, signaling and cell survival. J. Cell Sci. 115:3729-3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan, C., S. Cruet-Hennequart, A. Troussard, L. Fazli, P. Costello, K. Sutton, J. Wheeler, M. Gleave, J. Sanghera, and S. Dedhar. 2004. Regulation of tumour angiogenesis by integrin linked kinase (ILK). Cancer Cell 5:79-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Terpstra, L., J. Prud'homme, A. Arabian, S. Takeda, G. Karsenty, S. Dedhar, and R. St-Arnaud. 2003. Reduced chondrocyte proliferation and chondrodysplasia in mice lacking the integrin-linked kinase in chondrocytes. J. Cell Biol. 162:139-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Troussard, A. A., N. N. Mawji, C. Ong, A. Mui, R. St Arnaud, and S. Dedhar. 2003. Conditional knock-out of integrin-linked kinase demonstrates an essential role in protein kinase B/Akt activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:22374-22378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westerfield, M. 1993. The Zebrafish Book. University of Oregon Press, Eugene.

- 40.Wu, C. 1999. Integrin-linked kinase and PINCH: partners in regulation of cell-extracellular matrix interaction and signal transduction. J. Cell Sci. 112:4485-4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu, C., and S. Dedhar. 2001. Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and its interactors: a new paradigm for the coupling of extracellular matrix to actin cytoskeleton and signaling complexes. J. Cell Biol. 155:505-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, Y., L. Guo, K. Chen, and C. Wu. 2002. A critical role of the PINCH-ILK interaction in the regulation of cell shape change and migration. J. Biol. Chem. 277:318-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]