Significance

Recent studies show that cultivation of wild and domesticated plants was a protracted process that developed across southwest Asia. However, there have not been sufficient data to evaluate whether cereal cultivation and domestication developed in parallel in all the regions or at different times. Our findings indicate that cultivation of wild cereal forms during Pre-Pottery Neolithic A was common only in specific regions such as the southern-central Levant. Domesticated-type cereal chaff (>10%) is found in southern Syria around 10.7–10.2 ka Cal BP but appears around 400–1,000 y later in the other regions. Regionally diverse plant-based subsistence during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic could have contributed to (if not caused) chronological dissimilarities in the development of cereal cultivation and domestication in southwest Asia.

Keywords: plant domestication, agriculture, southwest Asia, Pre-Pottery Neolithic, archaeobotany

Abstract

Recent studies have broadened our knowledge regarding the origins of agriculture in southwest Asia by highlighting the multiregional and protracted nature of plant domestication. However, there have been few archaeobotanical data to examine whether the early adoption of wild cereal cultivation and the subsequent appearance of domesticated-type cereals occurred in parallel across southwest Asia, or if chronological differences existed between regions. The evaluation of the available archaeobotanical evidence indicates that during Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) cultivation of wild cereal species was common in regions such as the southern-central Levant and the Upper Euphrates area, but the plant-based subsistence in the eastern Fertile Crescent (southeast Turkey, Iran, and Iraq) focused on the exploitation of plants such as legumes, goatgrass, fruits, and nuts. Around 10.7–10.2 ka Cal BP (early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B), the predominant exploitation of cereals continued in the southern-central Levant and is correlated with the appearance of significant proportions (∼30%) of domesticated-type cereal chaff in the archaeobotanical record. In the eastern Fertile Crescent exploitation of legumes, fruits, nuts, and grasses continued, and in the Euphrates legumes predominated. In these two regions domesticated-type cereal chaff (>10%) is not identified until the middle and late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (10.2–8.3 ka Cal BP). We propose that the cultivation of wild and domesticated cereals developed at different times across southwest Asia and was conditioned by the regionally diverse plant-based subsistence strategies adopted by Pre-Pottery Neolithic groups.

Plant domestication is defined as an evolutionary process that resulted from the systematic cultivation of morphologically wild plants and eventually led to the appearance of agriculture (1, 2). In southwest Asia, the archaeobotanical evidence indicates that during the Epipaleolithic (c. 23–11.6 ka Cal BP), the plant-based subsistence focused primarily on the collection of wild plant species, including several species that are the ancestors of modern-day domesticated cereals and legumes (3–6). Around 11.5 ka Cal BP, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) in the Levant (11.6–10.7 ka Cal BP), there is evidence for the development of plant food production with the cultivation of various wild cereals such as wheat (Triticum) and barley (Hordeum) (7–10). Morphologically domesticated cereal species first appeared in the early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (EPPNB, c. 10.5 ka Cal BP) (11, 12). However, agriculture, defined as a system based on the production and consumption of and high reliance on domesticated plants (1), did not developed in southwest Asia until around 9.8 ka Cal BP, during the middle and late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (M/LPPNB) (1, 2, 13, 14).

In the last 25 y several hypotheses have been put forward to explain when and where plant cultivation and domestication started in southwest Asia. The “core-area” hypothesis, which was developed during the 1990s and early in the following decade (15–17), suggested that eight plant species, collectively referred to as the “founder crops” (18), had been selected and domesticated once in a single region or core area located in southeast Turkey. According to modern experimental work, the process of plant domestication was a rapid event that occurred as a result of human selection for morphologically domesticated species (19, 20). However, recent archaeobotanical data have demonstrated that before the establishment of domesticated plants in southwest Asia there was a period of cultivation of morphologically wild plants (7–10, 21). The new evidence indicates that predomestication cultivation occurred broadly at the same time in different regions (22, 23). Genetic evidence indicates that cultivation practices involved multiple wild progenitor populations located across different regions, and therefore it is not possible to pinpoint the exact origins of domesticated plants (24–29). Domesticated cereals first emerged during the EPPNB (c. 10.5 ka Cal BP), but they did not become dominant until 1,000 y later (11, 12), indicating that domesticated species evolved slowly (21) and that the rates of evolution during domestication were similar to those observed in wild species subject to natural selection (30, 31). In light of the data compiled in the last 30 y, plant domestication now is regarded as a protracted evolutionary process that occurred in multiple regions (32).

Archaeological evidence indicates that marked social, technological, and economic differences existed between the Epipaleolithic and Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) groups that inhabited southwest Asia (33–36). Several scholars argue that, given the lack of consistency in the archaeological record, terms such as “PPNA” and “PPNB” cannot be used to define all the aceramic groups that inhabited southwest Asia, especially those located in the eastern Fertile Crescent (modern-day Turkey, Iran, and Iraq) (33, 36–41). Recent excavations in the eastern Fertile Crescent have revealed significant differences in terms of architecture (42–45), lithic industries (39, 41, 46), burial customs (36), and animal (47–50) and plant exploitation (51–53) in comparison with sites in the Levant. Because of these differences, the aceramic Neolithic groups of the eastern Fertile Crescent are often referred to as “sedentary hunter/herder-gatherer groups” as opposed to the farming societies of the Levantine area (36, 54).

We hypothesize that these socio-cultural and economic differences between PPN sites in southwest Asia are reflected in the plant-based subsistence, as already shown by some authors (14, 32, 51–53), and could have influenced the development of plant cultivation and domestication in southwest Asia. Because thus far cereals have provided the most reliable data for characterizing the process of plant domestication, the aim of this paper is to explore the regional timing for the cultivation of wild and domesticated cereals across southwest Asia. To do so, the available archaeobotanical evidence from PPNA (11.7–10.7 ka Cal BP) and PPNB (10.7–8.2 ka Cal BP) sites is considered. In addition, we provide data for cereal domestication in the southern-central Levant area. This paper contributes to the understanding of the origins of agriculture, exploring the regional timing for the two main developments that occurred before the emergence of agriculture: the cultivation of morphologically wild cereal species and their subsequent domestication.

Cereal Cultivation vs. Wild Plant Gathering During the PPNA

One precondition for the emergence of morphologically domesticated plants is the adoption of cultivation practices involving wild plant species. Wild cereal cultivation was identified in archaeological sites during the 1980s and 1990s (7, 55, 56) and since then has been demonstrated at several PPN sites (the available evidence is summarized in ref. 57). The identification of wild plant cultivation is based on (i) the presence of cultivated-type grains (distinguished by their morphology and size; SI Text) and the gradual increase in grain size over time (58), both of which are associated with husbandry activities such as tillage (21, 59, 60), and (ii) the presence in archaeological sites of weeds characteristic of cultivated fields (56, 61) (see refs. 9 and 10 for additional criteria for identifying the early cultivation of wild cereals). Despite the limitations of any archaeobotanical record (see ref. 62), we consider that the types of plants represented in archaeological sites (e.g., cereals, legumes, fruits and nuts, other wild plants) and their proportions provide insights into the plants on which prehistoric groups relied for their subsistence and therefore should be considered, along with the abovementioned characteristics, when evaluating the presence and importance of practices such as cereal cultivation.

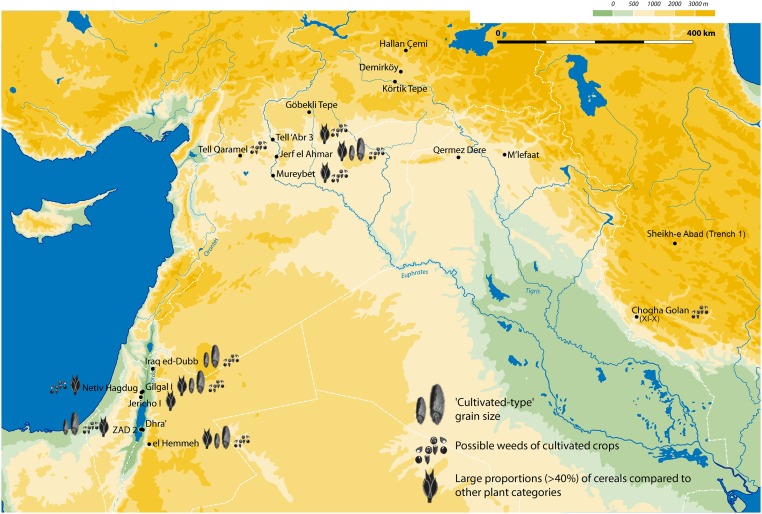

Several studies have shown that predomestication cultivation practices emerged around 11.7–10.7 ka Cal BP (the PPNA period in the Levant) in regions such as the southern-central Levant (7–9, 63–65), the Euphrates area (10, 56, 58), and the Zagros in Iran (23). However, the numbers of sites with evidence of predomestication cultivation (i.e., combined presence of cultivated-type grains and weeds of cultivated crops, along with the predominance of cereals in the archaeobotanical assemblage) varies considerably from one region to another (Fig. 1, based on Tables S1 and S2). The largest number of sites providing evidence for this practice are found in the southern-central Levant. Here cereals (mainly wild barley, Hordeum spontaneum) outnumber all other types of plants (Table S2), indicating they were preferentially exploited over other plant resources (7–9, 63–65). The PPNA sites in the Euphrates also show the prevalent exploitation of cereals, which we believe indicates their importance in the plant-based subsistence economy (10, 56). However, evidence for the cultivation of wild cereals has been identified so far only at Jerf el Ahmar and comprises wild barley and two-grained einkorn/rye (Triticum boeoticum/Secale) (10). In the eastern Fertile Crescent (southeast Turkey, Iran, and Iraq), the archaeobotanical evidence indicates a completely different subsistence strategy based on the exploitation of legumes and other wild plants (Table S2) (23, 51–53, 66, 67). At Chogha Golan (phases X–XI dated to 11.5–10.6 ka Cal BP) small-seeded legumes predominate, and within the large-seeded grasses goatgrass (Aegilops) outnumbers all other species including wild barley and wheat (23). At the neighboring site of Sheikh-e Abad plant exploitation focused on taxa such as club-rush (Scirpus), small-seeded wild grasses, and legumes (67). At sites in northern Iraq such as M’lefaat and Qermez Dere, large-seeded legumes and small-seeded wild grasses were mainly exploited, whereas wild barley and wheat were found in considerably lower proportions (51, 52). Contemporary sites such as Hallan Çemi and Demirköy in southeast Turkey show the prevalence of wild plants of the Cyperaceae, Brassicaceae, Chenopodiaceae, and Polygonaceae family, but few barley and einkorn remains were found (52, 53). At the nearby site of Körtik Tepe, seeds of the wild relatives of domesticated plants account for less than 6% of the plant assemblage (66).

Fig. 1.

Archaeological sites dated to 11.7–10.7 ka Cal BP (PPNA in the Levant) with published archaeobotanical evidence. Sites with combined presence of cultivated-type grains and arable flora, along with predominance of cereals over other plant categories, are considered to indicate wild cereal cultivation practices (based on Tables S1 and S2).

Table S1.

Summary of the PPNA sites in southwest Asia in which wild cereal cultivation has been discussed, along with the archaeobotanical evidence found

| Area | Site | Date, ka Cal BP | Taxa | Main arguments given | Ref(s). |

| Southern Levant | Dhrá | 11.7–11.4 | Barley (based on phytolith evidence) | Storage structure | 92 |

| Gilgal I | 11.5–11.1 | Barley and oat | Cultivated-type seed size, arable flora, seed abundance, storage evidence | 9, 93 | |

| Iraq ed-Dubb | 11.7–10.8 | Barley | Cultivated-type seed size, arable flora | 8 | |

| Netiv Hagdug | 11.3–10.8 | Barley | Arable flora | 9, 63 | |

| ZAD 2 | 11.2–10.8 | Barley | Cultivated-type seed size, arable flora | 64 | |

| el-Hemmeh | 11.1–10.7 | Barley | Cultivated-type seed size, arable flora | 65 | |

| Jericho I | 11.1–10.3 | Barley and emmer | Cultivated-type seed size | 94 | |

| Euphrates area | Mureybet (I-III) | 11.7–10.5 | Rye/2-grained einkorn, barley | Location of the site beyond natural cereal habitat, arable flora | 56, 76, 77 |

| Tell Ábr 3 | 11.5–11.2 | Rye/2-grained einkorn | Location of the site beyond natural cereal habitat | 10 | |

| Jerf el Ahmar | 11.4–10.7 | Barley, rye/2-grained einkorn | Cultivated-type seed size, arable flora, reduction in small gathered seeds of nonfounder plants, location of the site beyond natural cereal habitat, gradual adoption of founder crops | 10, 58, 61 | |

| Iran | Chogha Golan (XI–X) | 11.5–10.7 | Barley | Arable flora | 23, 95 |

At a number of sites cereal cultivation is not conclusive, e.g., Tell Ábr 3, Mureybet, and Netiv Hagdug (10, 63, 76, 77). At others, information regarding grain size is lacking (e.g., Dhrá, emmer grains from Jericho I). At Chogha Golan, increased barley grain size is attested in phase IX (contemporary with the EPPNB in the Levant) (95).

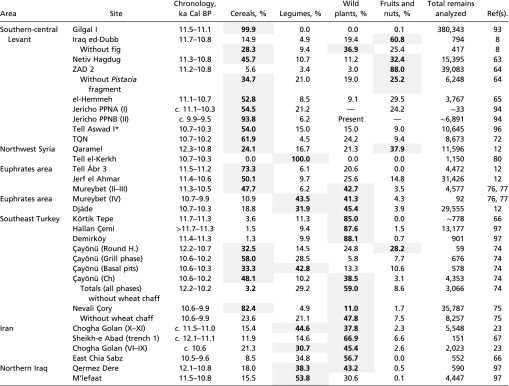

Table S2.

Summary of PPNA and EPPNB sites in southwest Asia and the proportions (%) for different plant categories: cereals (wheat, barley, oat, and rye), legumes, wild plants (including grasses), and fruits and nuts

|

The plant categories that constitute >50% of the plant assemblage are bold. Note that in some sites, unusually high concentrations of particular plant taxa were found in specific samples. In these cases, calculations excluding these plant taxa are also provided.

At Tell Aswad there is information regarding the proportions with which different plant categories are represented at the site (96), but no raw data are yet published. The indeterminate remains and amorphous residues found at this site, which account for the 7% of the assemblage, are not included in the calculations.

In accordance with the differences observed in the archaeological record between sites in the Levant and the eastern Fertile Crescent (33–50), the archaeobotanical evidence also highlights regional diversity in the plant-based subsistence around 11.7–10.7 ka Cal BP (PPNA in the Levant) (51–53). With few exceptions, wild cereals were the preferred type of plant exploited at sites in the southern-central Levant and the Euphrates area, and there is substantial evidence of cultivation at several sites. In the eastern Fertile Crescent, the plant-based subsistence focused instead on the exploitation of legumes and wild plants, with no clear evidence for wild cereal cultivation. The archaeobotanical data compiled in the last 30 y highlight the complexity of the subsistence strategies during this time, with cultivation of wild cereals being carried out only in specific locations (57).

Cultivation of Wild vs. Domesticated-Type Cereals During the PPNB

The domestication syndrome is defined as the set of features that differentiate domesticated crops from their wild ancestors (18, 21, 59). In grain crops, the domestication syndrome includes six major changes (21). Among these changes, the increased grain size and the loss of dispersal appendages (e.g., hairs and awns) represent evidence for semi-domestication, and the elimination or reduction of natural seed-dispersal mechanisms (e.g., nonshattering rachises) is regarded as the most reliable trait for the identification of morphologically domesticated cereals in archaeobotanical assemblages (68), that is, full domestication (21, but see ref. 19 for an alternative definition of plant domestication). Wild cereal species have brittle rachises with smooth scars (here referred to as “wild-type”), which enable the plant to shatter when ripe, thus shedding the grains. Domesticated cereal species, in contrast, are characterized by the presence of nonbrittle rachises with tough abscission scars (here referred to as “domesticated-type”). This trait hampers the natural reproduction of the plant (i.e., the spikelets remain attached to the ear and do not shatter spontaneously when mature), and they therefore require human intervention for their reproduction.

However, the occurrence of domesticated-type nonbrittle rachises in archaeological sites does not directly imply the exploitation of domesticated plant species. Observations in modern wild cereal stands indicate that genetically mutant plants that produce nonbrittle rachises are present in stands of morphologically wild species, at low proportions (one or two of every 2–4 million brittle-rachised plants) (19, 69). Additionally, in wild cereal species such as barley, around 10% of the basal rachises located in the lowest end of the ear produce domesticated-type scars (7). This evidence points out the need for detailed identification (i.e., wild- and domesticated-type, basal or nonbasal chaff) and quantification (i.e., examination of the proportions of wild- and domesticated-type scars) of the rachis remains to evaluate the development of domesticated cereals in archaeological sites.

The Evidence of Cereal Domestication at Tell Qarassa North

Tell Qarassa North (TQN) is a site located to the west of the Jebel el Arab region in southern Syria (Fig. 2), and eight radiocarbon dates from excavation area XYZ-67/68/69 indicate it was occupied during the EPPNB (Table S3) (70). Along with Tell Aswad in the Damascus Basin (71), TQN is one of only two sites in the southern-central Levant that provide a substantial archaeobotanical assemblage dated to this time period (72).

Fig. 2.

Archaeological sites dated to 10.7–10.2 ka Cal BP (EPPNB in the Levant) with published archaeobotanical records. Sites where domesticated-type rachis scars comprise >10% of the assemblage are considered to represent evidence of incipient cereal domestication (based on Table S6).

Table S3.

Available 14C dates from TQN (area XYZ-67/68/69)

| Phase | Space | Unit | Phase interpretation | Given sample no. | 14C y uncal | Cal BP | Dated material |

| I | B | 52C | 1st occupation | CNA - 1355 | 9,185 ± 40 | 10,487–10,244 | T. dicoccoides/dicoccum |

| II | A | 57 | 1st destruction | CNA - 1065 | 9,300 ± 45 | 10,651–10,298 | Pistacia sp. (Branch BB48) |

| Beta - 290929 | 9,340 ± 50 | 10,700–10,407 | T. boeoticum/monococcum | ||||

| A | 74 | — | — | — | — | ||

| B | 52B | — | — | — | — | ||

| III | A | 24b; 25 | 2nd occupation | CNA - 1353 | 9,252 ± 38 | 10,555–10,279 | T. boeoticum/monococcum |

| B | 52 | CNA - 1354 | 9,292 ± 48 | 10,648–10,291 | T. boeoticum/monococcum | ||

| IV | A | 24; 36; 37 | 2nd destruction | — | — | — | — |

| B | 14 | — | — | — | — | ||

| V | A | 21 | Abandonment | Beta - 272103 | 9,320 ± 50 | 10,683–10,301 | Wood charcoal |

| A | 34; 18; 5; 6 | Burial | Beta - 262213 | 9,100 ± 60 | 10,480–10,178 | T. dicoccoides/dicoccum | |

| VI | A | 15; 3; 4 | Surface layers | Beta - 277177 | 9,300 ± 50 | 10,653–10,296 | Triticum spp. |

| III–V | C | 47 | Food-processing area | — | — | — | — |

Dated units are in bold. Beta, Beta Analytic; CNA, Centro Nacional de Aceleradores.

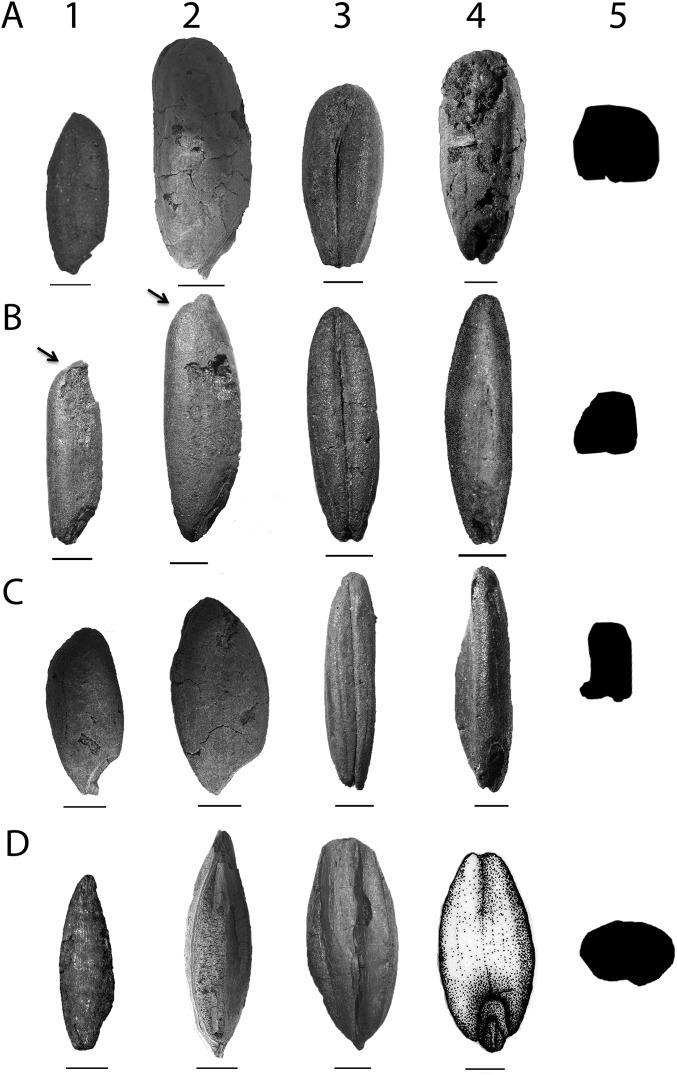

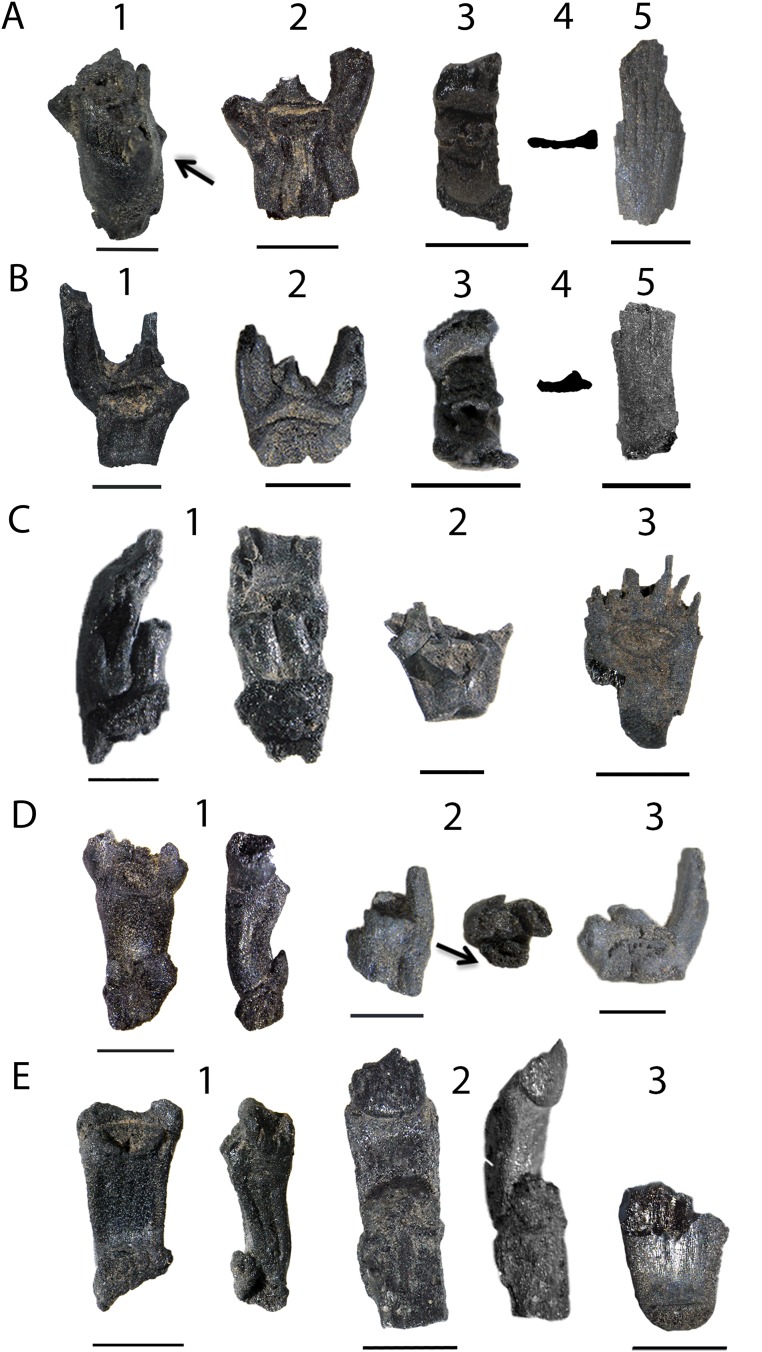

The cereal assemblage from TQN (area XYZ-67/68/69) comprises wild and domesticated-type species of emmer wheat (T. dicoccoides/dicoccum), one- and two-grained einkorn wheat (T. boeoticum/monococcum/urartu), and barley (Hordeum spontaneum/vulgare) (Fig. S1), which account for 56.8% of the assemblage (72). In the case of einkorn, the results indicate the predominance of two-grained forms [61.2% based on minimum number of individuals (MNI)] over one-grained ones (38.8% based on MNI) (72). The size ranges (i.e., breadth and thickness) of the wheat and barley grains are comparable to those observed in modern reference specimens from wild uncultivated and cultivated populations (the latter including wild and domesticated species) (SI Text and Table S4). Emmer, two-grained einkorn, and barley show a majority of cultivated-type specimens (>70.0%), whereas only 12.1% of the one-grained einkorn corresponds to cultivated-type grains. The final analysis of the rachis remains from TQN includes a total of 732 spikelet forks and rachis fragments (basal and nonbasal) from emmer, einkorn, and barley (Fig. S2). Of these, 305 could be identified as either wild-type or domesticated-type, but it was not possible to distinguish this trait on the remaining 427 remains (Table S5). Domesticated-type scars were identified on the emmer, einkorn, and barley chaff, and the proportions (21.1–41.2%) are larger than expected in wild cereal species (which is around 10%, as noted in ref. 7). The analysis on chaff remains identified to genus (i.e., Triticum) also shows large proportions of domesticated-type remains (35.8%).

Fig. S1.

Cereal grains from TQN: emmer (A), two-grained einkorn (B), one-grained einkorn (C), and barley (D). The first two grains in the left represent wild uncultivated-type and cultivated-type grains, respectively, in lateral view (e.g., A, 1–2). The rest of the grains are in ventral (e.g., A, 3), dorsal (e.g., A, 4), and transverse (e.g., A, 5) sections. The main difficulty in identification was the separation of two-grained einkorn and emmer. In the ventral/dorsal view, the caryopses of two-grained einkorn were more slender than those of emmer and commonly showed attenuated apical and embryo ends, unlike the blunt ends found in emmer grains (96). In two-grained einkorn the lateral view of the caryopsis was parallel to slightly curved, whereas in emmer the dorsal surface was convex and humpbacked in some specimens, and the ventral face was flat to slightly convex. A key character of two-grained einkorn was the apical compression or indentation in lateral view (marked with an arrow in B, 1–2) (97). In the transverse section, two-grained einkorn was often asymmetric and was commonly rectangular to square in shape, whereas emmer grains were evenly rounded to somewhat angular and were commonly symmetric.

Table S4.

Summary of the cereal grains from TQN that, based on grain morphology and size, correspond to wild uncultivated-type and cultivated-type (comprising wild and domesticated) forms (SI Text)

| Grain size at TQN | Wild uncultivated, % | Wild/domestic cultivated, % | Total grains |

| Emmer | 18.2 | 81.8 | 220 |

| One-grained einkorn | 87.9 | 12.1 | 91 |

| Two-grained einkorn | 28.9 | 71.1 | 121 |

| Barley | 27.1 | 72.9 | 48 |

Fig. S2.

Wild and domesticated-type cereal chaff from TQN: emmer (A), einkorn (B), barley (C), indeterminate wheat (D), and indeterminate wheat/barley (E). For emmer (A) and einkorn (B), examples of spikelet forks with domesticated-type (A, 1 and B, 1) and wild-type (A, 2 and B, 2) upper or lower scars, transverse view of the spikelet fork (A, 3 and B, 3), transverse view of a glume base (A, 4 and B, 4), and lateral view of a glume base (A, 5 and B, 5) are given. The arrow in A, 1 and D, 2 shows a domesticated-type emmer scar clearly lifted from the internode surface. For barley (C), indeterminate wheat (D), and indeterminate wheat/barley (E) examples include basal spikelet forks/rachis remains with domesticated-type scar (C, 1; D, 1; and E, 1), nonbasal spikelet forks/rachis remains with domesticated-type scar (C, 2; D, 2; and E, 2), and nonbasal spikelet forks/rachis remains with wild-type scar (C, 3; D, 3; and E, 3).

Table S5.

Summary of the proportions of wild- and domesticated-type cereal scars derived from basal and nonbasal chaff at TQN

| Taxa | Status | Nonbasal | Basal | Total remains by taxa and status | |||

| Counts | % fragment counts | Counts | % fragment counts | Counts | % fragment counts | ||

| Triticum spp. | Wild | 56 | 70.9 | 30 | 54.5 | 86 | 64.2 |

| Domestic | 23 | 29.1 | 25 | 45.5 | 48 | 35.8 | |

| T. boeoticum /monococcum (1-/2-grained) | Wild | 10 | 71.4 | — | — | 10 | 71.4 |

| Domestic | 4 | 28.6 | — | — | 4 | 28.6 | |

| T. dicoccoides/dicoccum | Wild | 15 | 78.9 | — | — | 15 | 78.9 |

| Domestic | 4 | 21.1 | — | — | 4 | 21.1 | |

| Hordeum spontaneum/vulgare | Wild | 9 | 69.2 | 1 | 25.0 | 10 | 58.8 |

| Domestic | 4 | 30.8 | 3 | 75.0 | 7 | 41.2 | |

| Triticum/Hordeum indeterminate | Wild | 32 | 65.3 | 20 | 27.8 | 52 | 43.0 |

| Domestic | 17 | 34.7 | 52 | 72.2 | 69 | 57.0 | |

| Total Triticum spp. | Total wild | 85 | 75.9 | 30 | 54.5 | 115 | 68.9 |

| Total domestic | 27 | 24.1 | 25 | 45.5 | 52 | 31.1 | |

| Total cereals | Total wild | 126 | 72.4 | 51 | 38.9 | 177 | 58.0 |

| Total domestic | 48 | 27.6 | 80 | 61.1 | 128 | 42.0 | |

This dataset includes the final analyses of all the samples retrieved from the site. The Triticum/Hordeum category comprises primarily basal chaff and lower scars.

On the basis of these results it can be concluded that by 10.7–10.2 ka Cal BP there are positive signs that barley, emmer, and einkorn were being cultivated at TQN (72) and that at least some of the remains of grains and/or chaff bear the characteristics of fully evolved domesticated specimens. The evidence of einkorn domestication at TQN probably involves two-grained einkorn species (i.e., T. boeoticum thaoudar or T. urartu). In terms of the numbers of grains, two-grained einkorn forms were predominant, and morphometric analyses suggested that, unlike the one-grained forms, they had characteristics similar to cultivated-type forms. The overall proportions of domesticated-type cereal chaff are <50% of the total sample for each of the three cereals and therefore indicate that the site represents an early stage in the process of cereal domestication. The presence of considerable proportions of uncultivated-type cereal grains suggests that at TQN, in addition to cultivation, cereals could have been gathered from wild stands.

The Regional Evidence for Cereal Domestication (Early/Middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B)

The archaeobotanical evidence for the EPPNB period (10.7–10.2 ka Cal BP) indicates regional differences in the proportions of wild and domesticated-type cereals (Fig. 2). In southern Syria, there are clear signs of cultivation of domesticated-type barley at Tell Aswad (12) and of emmer, einkorn, and barley at TQN (i.e., the presence of c. 30% of domesticated-type cereal chaff). However, in the rest of contemporary sites domesticated-type chaff accounts for c. 10% or even less, indicating continued exploitation of morphologically wild species (10, 12, 23, 66, 67, 73–77). The evidence suggests that the pace with which morphologically domesticated cereals appeared during the EPPNB in southwest Asia varied regionally.

The lack of evidence for cereal domestication during the EPPNB on the Upper Euphrates, in southeast Turkey, and the Zagros is not surprising if we consider that the plant-based subsistence focused primarily on the exploitation of plants other than cereals (Table S2). In the Euphrates area, a change in the subsistence is found during this time. The widespread exploitation of cereals during the PPNA is replaced by the exploitation of lentils (Lens), pea/vetch/grass pea (Pisum/Vicia/Lathyrus), and small-seeded legumes as suggested by their predominance in the archaeobotanical assemblages (10, 76, 77). In southeast Turkey, archaeobotanical (73–75) and isotope (78, 79) evidence indicates that legumes such as lentil, bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia), and pea seem to have been consumed preferentially during the EPPNB. The importance of legumes in the subsistence is also shown at other contemporary sites such as Tell el-Kerkh in northwest Syria (80) and Ahihud in Israel (81), where domesticated-type chickpea and faba bean (Vicia faba) have been found. In the Zagros, continued exploitation of wild plants, including goatgrass and small-seeded wild grasses and legumes, is attested (23, 66). The presence of these particular species might be linked to caprine-management activities identified in the area (49), because goatgrass and small-seeded legumes are commonly regarded as fodder plants (82).

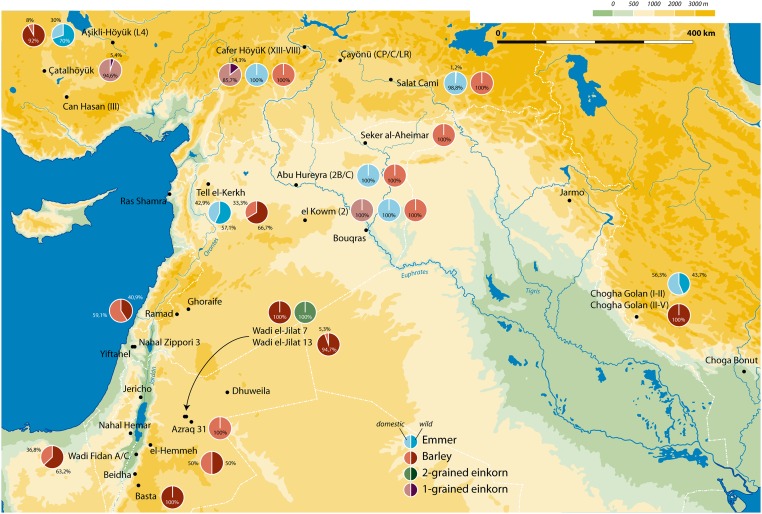

With the onset of the middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (MPPNB) in the Levant (10.2–9.5 ka Cal BP), domesticated-type cereal species (>10%) are identified in most of the regions across southwest Asia (Fig. 3, based on Table S6). In Turkey, the earliest evidence includes domesticated-type emmer, barley, and one-grained einkorn, which are found around 10.3–10.2 ka Cal BP in central Anatolia (83–85) and the southeast area (86). In the Euphrates and northwest Syria domesticated free-threshing wheat (Triticum aestivum/durum) is found c. 9.8–9.3 ka Cal BP (87), although there is no evidence for domesticated-type hulled cereals (barley in this case) until c. 9.3 ka Cal BP (12). In the Zagros, the earliest record for domesticated-type cereals found so far, c. 9.8 ka Cal BP, involves emmer (23). The spread of domesticated-type cereals is correlated with an overall increase in the presence of cereals as opposed to other plants in archaeobotanical assemblages, although exceptions exist (8, and see data in ref. 46). The information compiled so far indicates that cereals constituted 46.2% of the archaeobotanical assemblages at sites dated to 10.2–7.4 ka Cal BP, in comparison with the average of 22.4% found at sites dated to 13.8–10.2 ka Cal BP (based on ref. 46). However, the evidence suggests that there is not a directional change toward increased proportions of domesticated-type chaff, because these proportions are sometimes similar to or even lower than those seen during the EPPNB in southern Syria (c. 30%) (Figs. 2 and 3). That crops may have moved outside their natural area of distribution at different stages (i.e., wild, wild-cultivated, domesticated, or a mixture) and hybridized with local wild genetic lineages (24–27), as well as the continued exploitation of wild cereal stands, should be considered as possible explanations for the protracted establishment of domesticated cereals in southwest Asia.

Fig. 3.

Archaeological sites dated to 10.2–8.3 ka Cal BP (M/LPPNB in the Levant) with published archaeobotanical evidence. Sites where domesticated-type rachis scars comprise >10% of the assemblage are considered to represent evidence of incipient cereal domestication (based on Table S6).

Table S6.

Summary of the proportions of wild- and domesticated-type cereal scars at PPNA and PPNB sites in southwest Asia

| Area | Site | Date, ka Cal BP | Taxa | % wild-type | % domestic-type | Based on n of wild/domestic chaff | Ref(s). |

| Southern and central Levant | Ohalo II | c. 23–21 | Emmer | 64.0 | 36.0 | 148 | 4 |

| Ohalo II | c. 23–21 | Barley | 75.0 | 25.0 | 320 | 4 | |

| Netiv Hagdud | 11.3–10.8 | Barley | 96.0 | 4.0 | 3,277 | 63 | |

| Netiv Hagdud | 11.3–10.8 | Emmer | 100.0 | 0.0 | 123 | 63 | |

| ZAD 2 | 11.2–10.8 | Barley | 71.1 | 28.9 | 38 | 64 | |

| el-Hemmeh (PPNA) | 11.1–10.7 | Barley | 94.3 | 5.7 | 53 | 65 | |

| el-Hemmeh (PPNA) | 11.1–10.7 | Emmer | 100.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 65 | |

| TQN | 10.7–10.2 | 1-/2-grained einkorn | 71.4 | 28.6 | 14 | — | |

| TQN | 10.7–10.2 | Emmer | 78.9 | 21.1 | 19 | — | |

| TQN | 10.7–10.2 | Barley | 58.8 | 41.2 | 17 | — | |

| Aswad I | 10.7–10.3 | Emmer | 95.7 | 4.3 | 231 | 12 | |

| Aswad (van Zeist) | c. 10.5 | Barley | 70.2 | 29.8 | 114 | 12 | |

| Aswad (Willcox) | c. 10.5 | Barley | 64.8 | 35.2 | 54 | 12 | |

| Wadi Jilat 7 | 10.2–9.3 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 66 | 8 | |

| Wadi Jilat 7 | 10.2–9.3 | 2-grained einkorn | 0.0 | 100.0 | 6 | 8 | |

| el-Hemmeh (LPPNB) | 9.8–9.6 | Barley | 50.0 | 50.0 | 44 | 65 | |

| Azraq 31 | 9.5–9.2 | Barley | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2 | 8 | |

| Basta | 9.5–9.0 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 33 | 98 | |

| Wadi Fidan A and C | 9.3–8.7 | Barley | 63.2 | 36.8 | 19 | 8 | |

| Ramad | 9.3–8.6 | Barley | 40.9 | 59.1 | 455 | 12 | |

| Wadi Jilat 13 | 9.0–8.6 | Barley | 94.7 | 5.3 | 19 | 8 | |

| Southeast and central Turkey | Çayönü (R, G, BP, Ch) | 10.6–10.2 | Wheat | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2,264 | 74 |

| Çayönü (R, G, BP, Ch) | 10.6–10.2 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 129 | 74 | |

| Nevali Çory | 10.6–9.9 | 1-grained einkorn | 86.2 | 13.8 | 282 | 12 | |

| Cafer Höyük (XIII-VIII) | 10.3–9.4 | 1-grained einkorn | 14.3 | 85.7 | 7 | 86 | |

| Cafer Höyük (XIII-VIII) | 10.3–9.4 | Emmer | 0.0 | 100.0 | 17 | 86 | |

| Cafer Höyük (XIII-VIII) | 10.3–9.4 | Barley | 0.0 | 100.0 | 10 | 86 | |

| Çayönü (CP/C/LR) | 10.2–8.8 | Wheat | 0.0 | 100.0 | 867 | 76 | |

| Çayönü (CP/C/LR) | 10.2–8.8 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 74 | |

| Aşıklı Höyük (L4) | >9.8–9.5 | Emmer | 70.0 | 30.0 | 30 | 12 | |

| Aşıklı Höyük (L4) | >9.8–9.5 | Barley | 92.0 | 8.0 | 25 | 12 | |

| Çatalhöyük | 9.1–8.4 | 1-grained einkorn | 5.4 | 94.6 | 945 | 99 | |

| Northern Syria | Tell Qaramel | 12.3–10.8 | 1-grained einkorn | 100.0 | 0.0 | 14 | 12 |

| Jerf el Ahmar | 11.4–10.7 | 2-grained einkorn | 100.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 12 | |

| Jerf el Ahmar | 11.4–10.7 | Barley | 99.8 | 0.2 | 3,333 | 12 | |

| Mureybet II | 11.7–11.2 | Emmer | 0.0 | 100.0 | 1 | 100 | |

| Mureybet III | 11.3–10.5 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 6 | 76, 77 | |

| Dja´de | 10.7–10.3 | 2-grained einkorn | 100.0 | 0.0 | 16 | 12 | |

| Dja´de | 10.7–10.3 | Barley | 98.7 | 1.3 | 155 | 12 | |

| Seker Aheimar | c. 9.3 | Barley | 0.0 | 100.0 | 54 | 12 | |

| El Kowm (2) | c. 8.7 | 1-grained einkorn | 0.0 | 100.0 | 7 | 101 | |

| El Kowm (2) | c. 8.7 | Barley | 0.0 | 100.0 | 76 | 101 | |

| El Kowm (2) | c. 8.7 | Emmer | 0.0 | 100.0 | 36 | 101 | |

| Northern Syria | Tell el-Kerkh | c. 8.2 | Emmer | 57.1 | 42.9 | 35 | 12 |

| Tell el-Kerkh | c. 8.2 | Barley | 66.7 | 33.3 | 3 | 12 | |

| Abu Hureyra (2B/C) | c. 8.2 | Emmer | 0.0 | 100.0 | 23 | 86 | |

| Abu Hureyra (2B/C) | c. 8.2 | Barley | 0.0 | 100.0 | 19 | 86 | |

| Iran and the Tigris | Chogha Golan (X–XI) | c. 11.5–10.6 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 272 | 23 |

| Chogha Golan (VI–IX) | c. 10.8–9.8 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 141 | 23 | |

| Chogha Golan (IV–V) | c. 10.2–9.8 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 750 | 23 | |

| Chogha Golan (III–II) | c. 10.2–9.7 | Barley | 100.0 | 0.0 | 42 | 23 | |

| Chogha Golan (I–II) | c. 9.8 | Emmer | 0.0 | 100.0 | 25 | 23 | |

| Chogha Golan (I–II) | c. 9.8 | Emmer | 43.8 | 56.3 | 16 | 95 | |

| Salat Cami | c. 8.3 | Emmer | 1.2 | 98.8 | 86 | 12 | |

| Salat Cami | c. 8.3 | Barley | 0.0 | 100.0 | 15 | 12 |

Calculations exclude rachises identified as “possible domestic” in ref. 12, chaff remains identified with uncertainty to species level, e.g., rachis remains identified as Hordeum spontaneum/sativum at Wadi Jilat (8). The evidence of cereal domestication at Çayönü should be regarded with caution until the material has been quantified following recent classifications (12), and therefore it is not present in Fig. 2. At Cafer Höyük remains identified as T. monococcum or T. turgidum ssp. dicoccum may correspond to a different species (i.e., T. macha) (86). Note that records from el Kowm (2) include domestic-type glume bases, and in the case of einkorn, four out of seven are basal spikelet forks (86).

Conclusions

Several studies have shown that strong socio-cultural differences existed among PPN groups in southwest Asia (33–54). This work shows that the plant-based subsistence strategies were regionally diverse during the PPNA and the EPPNB. Cereal exploitation was predominant in regions such as the southern-central Levant and the Euphrates, whereas in the eastern Fertile Crescent the exploitation of other plant resources predominated. Thus we must reconsider the importance that is often uncritically attributed to cereals when evaluating the plant-based subsistence strategies of the PPN and should emphasize the key role that other plant taxa, such as legumes and large-/medium-seeded wild grasses (e.g., goatgrass), played during this time.

The archaeobotanical evidence shows that some domesticated-type crops (e.g., einkorn, emmer, barley, faba bean) appeared in the southern-central Levant, and others (e.g., chickpea) occurred in other regions such as northwest Syria. This diversity indicates that plant domestication (in the broadest sense of the term) is a process that occurred in multiple regions across southwest Asia and cannot be linked with a single core area. For cereals such as wheat and barley, we propose that the domestication process was protracted (21, 30) and was regionally diverse in terms of timing. The results indicate chronological dissimilarities in the adoption of predomestication cultivation practices and in the emergence of domesticated species in various regions. However, we believe that in the regions where cereal exploitation was not common practice during the PPN, similar management processes involving different plant species could have existed. Studies that explore the cultivation and domestication processes of plants other than cereals will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the scale and nature of agriculture in southwest Asia.

Materials and Methods

Nonwoody plant macroremains from TQN were identified using the reference collection housed at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London. The identification of domesticated species was undertaken only in the case of chaff remains and was based on the presence of nonbrittle or tough rachises (Fig. S2) (12). The identification of domesticated emmer chaff (Fig. S2A) was based on ref. 88. The identification of cultivated- and uncultivated-type grains was based on grain size and morphology (SI Text and Fig. S1) (89). The raw data from TQN are presented in SI Text and Tables S4 and S5.

SI Text: Summary of the Archaeobotanical Analyses at TQN

At TQN a total of 58 flotation samples were recovered from excavation area XYZ-67/68/69 and 1,590.5 L were processed (see ref. 72 for further details). Flotation was carried out with a 100-L Siraf-type machine, following standard procedures. The sorting of the flotation samples was conducted in the Department of Geography, Prehistory and Archaeology, University of the Basque Country (UPV-EHU), Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain.

Wild cereal species that have been cultivated are similar to domesticated species in grain size and shape (e.g., note early claims for cereal domestication at PPNA sites on the basis of grain size/shape). We consider that the identification to the species level (i.e., wild/domesticated) of cereal grains is not possible at early Neolithic sites. Therefore we refer to both wild and domesticated species in the identifications of cereal grains from TQN.

To avoid confusion between two completely different, although interrelated, processes (i.e., plant cultivation and plant domestication) (1), terms such as “domesticated-type,” which are commonly used to describe cultivated-type grains but not necessarily domesticated species, have been avoided when describing grain characteristics. Instead of these terms, we decided to refer to “wild uncultivated-type” (i.e., unmanaged) and “cultivated-type” grains, the latter comprising both wild and domesticated species. The criteria used in the distinction of these types rely on morphological characteristics as well as on metrical analyses of both modern and ancient material (Fig. S2) (89). For the ancient material, the breadth (width) and thickness (height) of emmer, einkorn, and barley were considered. Grains were measured using a Nikon binocular SMZ 800 stereomicroscope and NIS Elements Documents 3.0 software (Nikon) at different magnifications. Seeds with obvious swelling or protrusion or those in a poor state of preservation (i.e., with the testa removed) were not included in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Willcox, S. Riehl, E. Weiss, M. Heun, E. Asouti, and T. Richter for helpful comments and discussion on earlier drafts of this paper and the anonymous reviewers who stimulated the discussion of the data and made valuable comments. The research was carried out at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) with financial support of the Basque Government through Pre-Doctoral Grant BFI.09.249 and the UPV/EHU Research Group IT622-13/UFI 11-09. The Qarassa project is funded by the Spanish Institute of Cultural Heritage (Ministry of Culture); Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, R+D Projects HAR2013-47480-P and HAR2016-74999-P; the Shelby White and Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications; and the Palarq and Gerda Henkel Foundations.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1612797113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zeder MA. Core questions in domestication research. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(11):3191–3198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501711112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris DR. Themes and concepts in the study of early agriculture. In: Harris DR, editor. The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia. Univ College of London Press; London: 1996. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss E, Wetterstrom W, Nadel D, Bar-Yosef O. The broad spectrum revisited: Evidence from plant remains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(26):9551–9555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402362101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snir A, et al. The origin of cultivation and proto-weeds, long before Neolithic farming. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0131422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillman GC, Colledge SM, Harris DR. 1989. Plant-food economy during the Epipalaeolithic period at Tell Abu Hureyra, Syria: Dietary diversity, seasonality, and modes of exploitation. Foraging and Farming: The Evolution of Plant Exploitation, One World Archaeology Series 13, eds Harris DR, Hillman GC (Unwin Hyman, London), pp 240–268.

- 6.Hillman GC. The economy of the two settlements at Abu Hureyra. In: Moore AMT, Hillman GC, Legge AJ, editors. Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford, UK: 2000. pp. 327–398. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kislev ME. 1989. Pre-domesticated cereal in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A. People and Culture in Change, British Archaeological Reports International Series 508, ed Hershkovitz I (British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, UK), pp 147–151.

- 8.Colledge S. 2001. Plant Exploitation on Epipalaeolithic and Early Neolithic Sites in the Levant, British Archaeological Reports International Series 986 (British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, UK)

- 9.Weiss E, Kislev ME, Hartmann A. Anthropology. Autonomous cultivation before domestication. Science. 2006;312(5780):1608–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.1127235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willcox G, Fornite S, Herveux L. Early Holocene cultivation before domestication in northern Syria. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2008;17(3):313–325. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanno K, Willcox G. How fast was wild wheat domesticated? Science. 2006;311(5769):1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1124635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanno K, Willcox G. Distinguishing wild and domesticated wheat and barley spikelets from early Holocene sites in the Near East. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2012;21(2):107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nesbitt M. When and where did domesticated cereals first occur in southwest Asia? In: Cappers RTJ, Bottema S, editors. The Dawn of Farming in the Near East, Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence and Environment. Ex-oriente; Berlin: 2002. pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asouti E, Fuller DQ. A contextual approach to the emergence of agriculture in southwest Asia: Reconstructing early Neolithic plant-food production. Curr Anthropol. 2013;54(3):299–345. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lev-Yadun S, Gopher A, Abbo S. Archaeology. The cradle of agriculture. Science. 2000;288(5471):1602–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopher A, Abbo S, Lev-Yadun S. The ‘when’, the ‘where’ and the ‘why’ of the Neolithic Revolution in the Levant. Doc Praehist. 2001;28:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heun M, et al. Site of einkorn wheat domestication identified by DNA fingerprinting. Science. 1997;278(5341):1312–1314. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zohary D, Hopf M, Weiss E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World. 4th Ed Oxford Univ Press; Oxford, UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillman GC, Davies MS. Measured domestication rates in wild wheats and barley under primitive cultivation, and their archaeological implications. J World Prehist. 1990;4(2):157–222. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbo S, Gopher A, Rubin B, Lev-Yadun S. On the origins of Near Eastern founder crops and the ‘dump-heap hypothesis’. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2005;52(5):491–495. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller DQ. Contrasting patterns in crop domestication and domestication rates: Recent insights from Old World archaeobotany. Ann Bot (Lond) 2007;100:903–924. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willcox G. Anthropology. The roots of cultivation in southwestern Asia. Science. 2013;341(6141):39–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1240496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riehl S, Zeidi M, Conard NJ. Emergence of agriculture in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains of Iran. Science. 2013;341(6141):65–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1236743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poets AM, Fang Z, Clegg MT, Morrell PL. Barley landraces are characterized by geographically heterogeneous genomic origins. Genome Biol. 2015;16:173. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0712-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allaby RG. Barley domestication: The end of a central dogma? Genome Biol. 2015;16:176. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0743-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Civáň P, Ivaničová Z, Brown TA. Reticulated origin of domesticated emmer wheat supports a dynamic model for the emergence of agriculture in the fertile crescent. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e81955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pourkheirandish M, et al. Evolution of the grain dispersal system in barley. Cell. 2015;162(3):527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azhaguvel P, Komatsuda T. A phylogenetic analysis based on nucleotide sequence of a marker linked to the brittle rachis locus indicates a diphyletic origin of barley. Ann Bot (Lond) 2007;100(5):1009–1015. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrell PL, Clegg MT. Genetic evidence for a second domestication of barley (Hordeum vulgare) east of the Fertile Crescent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(9):3289–3294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611377104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuller DQ, Asouti E, Purugganan MD. Cultivation as slow evolutionary entanglement: Comparative data on rate and sequence of domestication. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2012;21(2):131–145. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purugganan MD, Fuller DQ. Archaeological data reveal slow rates of evolution during plant domestication. Evolution. 2011;65(1):171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuller DQ, Willcox G, Allaby RG. Cultivation and domestication had multiple origins: Arguments against the core area hypothesis for the origins of agriculture in the Near East. World Archaeol. 2012;43(4):628–652. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bar-Yosef O, Belfer-Cohen A. The Levantine ‘PPNB’ interaction sphere. In: Hershkovitz I, editor. People and Culture in Change. British Archaeological Reports; Oxford, UK: 1989. pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gebel HGK. There was no centre: The polycentric evolution of the Near Eastern Neolithic. Neo-Lithics. 2004;1(04):28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aurenche O, et al. Proto-neolithic and neolithic cultures in the Middle East. The birth of agriculture, livestock rising and ceramics: A calibrated 14C chronology 12,500-5,500 cal BC. Radiocarbon. 2001;43(3):1191–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watkins T. Supra-regional networks in the Neolithic of Southwest Asia. J World Prehist. 2008;21(1):139–171. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aurenche O, Kozłowski S. La Naissance du Néolithique au Proche-Orient. Éditions Errance; Paris: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watkins T. The Neolithic in transition - how to complete a paradigm shift. Levant. 2013;45(2):149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peasnall BL. 2000. The Round House Horizon Along the Taurus-Zagros Arc: A Synthesis of Recent Excavations of Late Epipaleolithic and Early Aceramic Sites in Southeastern Anatolia and Northeastern Iraq. Ph.D. thesis (Univ of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA)

- 40.Özbaşaran M, Buitenhuis H. Proposal for a regional terminology for Central Anatolia. In: Gérard F, Thissen L, editors. The Neolithic of Central Anatolia. Internal Developments and External Relations During the 9th–6th Millennia cal BC. Ege Yayınları; Istanbul: 2002. pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hojjat D. 2015. An Introduction to the Neolithic Revolution of the Central Zagros, Iran, British Archaeological Reports International Series 2746 (British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, UK)

- 42.Peters J, Schmidt K. Animals in the symbolic world of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey: A preliminary assessment. Anthropozoologica. 2004;39(1):179–218. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt K. Göbekli Tepe the stone age sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Documenta Prehistorica. 2010;37:239–256. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hauptmann H. The Urfa region. In: Özdoğan BN, editor. Neolithic in Turkey. The Cradle of Civilization, New Discoveries. Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları; Istanbul: 1999. pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watkins T. The origins of house and home? World Archaeol. 1990;21(3):336–347. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maeda O, Lucas L, Silva F, Tanno KI, Fuller DQ. Narrowing the harvest: Increasing sickle investment and the rise of domesticated cereal agriculture in the Fertile Crescent. Quat Sci Rev. 2016;145:226–237. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Redding RW. Breaking the mold: A consideration of variation in the evolution of animal domestication. In: Vigne JD, Peters J, Helmer D, editors. The First Steps of Animal Domestication: New Archaeobiological Approaches. Oxbow; Oxford, UK: 2005. pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters J, von den Driesch A, Helmer D. The upper Euphrates-Tigris basin: Cradle of agro-pastoralism? In: Vigne JD, Peters J, Helmer D, editors. The First Steps of Animal Domestication: New Archaeobiological Approaches. Oxbow; Oxford, UK: 2005. pp. 96–124. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeder MA. 2008. Animal domestication in the Zagros: An update and directions for future research. Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on the Archaeozoology of Southwestern Asia and Adjacent Areas, Archaeozoology of the Near East VIII, eds Villa E, Gourichon L, Choyke A, Buitenhuis H (Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée, Lyon, France), pp 243–277.

- 50.Zeder MA. The Origins of agriculture in the Near East. Curr Anthropol. 2012;53(4):S221–S235. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Savard M, Nesbitt M, Gale R. Archaeobotanical evidence for early Neolithic diet and subsistence at M’lefaat (Iraq) Paéorient. 2003;29(1):93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savard M, Nesbitt M, Jones MK. The role of wild grasses in subsistence and sedentism: New evidence from the northern Fertile Crescent. World Archaeol. 2006;38(2):179–196. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenberg M, et al. Hallan Çemi Tepesi: Some preliminary observations concerning early Neolithic subsistence behaviors in eastern Anatolia. Anatolica. 1995;21:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matthews R, et al. 2016 Investigating the Early Neolithic of western Iran: The Central Zagros Archaeological Project (CZAP). Antiquity Project Gallery. Available at antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/matthews323/. Accessed June 24, 2016.

- 55.Hillman GC. Late Pleistocene changes in wild plant-foods available to hunter-gatherers of the northern Fertile Crescent: Possible preludes to cereal cultivation. In: Harris DR, editor. The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia. Univ College of London Press; London: 1996. pp. 159–203. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colledge S. 1998. Identifying pre–domestication cultivation using multivariate analysis. The Origins of Agriculture and Crop Domestication, eds Damania AB, Valkoun J, Willcox G, Qualset CO. (International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Area, Aleppo, Syria), pp 121–131.

- 57.Arranz-Otaegui A, Ibañez JJ, Zapata L. Hunter-gatherer plant use in southwest Asia: The path to agriculture. In: Hardy K, Kubiak-Martens L, editors. Wild Harvest: Plants in the Hominin and Pre-Agrarian Human Worlds. Oxbow Books; Oxford, UK: 2016. pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willcox G. Measuring grain size and identifying Near Eastern cereal domestication: Evidence from the Euphrates valley. J Archaeol Sci. 2004;31(2):145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harlan JR, de Wet JMJ, Price EG. Comparative evolution of cereals. Evolution. 1973;27(2):311–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1973.tb00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zohary D. Unconscious selection and the evolution of domesticated plants. Econ Bot. 2004;58(1):5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Willcox G. Searching for the origins of arable weeds in the Near East. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2012;21(2):163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colledge S, Conolly J, Shennan S. Archaeobotanical evidence for the spread of farming in the eastern Mediterranean. Curr Anthropol. 2004;45:S35–S58. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kislev ME. Early agriculture and palaeoecology of Netiv Hagdud. In: Bar-Yosef O, Gopher A, editors. An Early Neolithic Village in the Jordan Valley. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA: 1997. pp. 209–236. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edwards PC, et al. From the PPNA to the PPNB: New views from the southern Levant after excavations at Zahrat adh-Dhra’ 2 in Jordan. Paéorient. 2004;30(2):21–60. [Google Scholar]

- 65.White CE, Makarewicz CA. Harvesting practices and early Neolithic barley cultivation at el–Hemmeh, Jordan. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2012;21(2):85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riehl S, et al. Plant use in three Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites of the northern and eastern Fertile Crescent: A preliminary report. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2012;21(2):95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Whitlam J, et al. The Plant macrofossil evidence from Sheikh-e Abad: First impressions. In: Matthews R, Matthews W, Mohammadifar Y, editors. The Earliest Neolithic of Iran: 2008 Excavations at Sheikh-E Abad and Jani. Oxbow Books and The British Institute for Persian Studies; Oxford, UK: 2013. pp. 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hammer K. Das Domestikationssyndrom. Kultupfl. 1984;32(1):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharma HC, Waines JG. Inheritance of tough rachis in crosses of Tritieum monococcum and T. boeoticum. J Hered. 1980;71(3):214–216. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ibañez JJ, et al. The early PPNB levels of Tell Qarassa North (Sweida, southern Syria) Antiquity Project Gallery 2010 . Available at antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/ibanez325/. Accessed November 14, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stordeur D, et al. 2010. Le PPNB de Syrie du Sud à travers les découvertes récentes à tell Aswad. Hauran V La Syrie Du Sud Du Néolithique À L'antiquité Tardive Recherches Récentes Actes Du Colloque De Damas 2007, eds Al-Maqdissi M, Braemer F, Dentzer JM (Beyrouth) Vol 1, pp 41–68.

- 72.Arranz-Otaegui A, et al. Crop husbandry activities and wild plant gathering, use and consumption at the EPPNB Tell Qarassa North (south Syria) Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2016;25(6):629–645. [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Zeist W, de Roller GJ. The plant husbandry of aceramic Çayönü, SE Turkey. Palaeohistoria. 1991/1992;33/34:65–96. [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Zeist W, de Roller GJ. The Çayönü archaeobotanical record. In: van Zeist W, editor. Reports on Archaeobotanical Studies in the Old World. The Groningen Institute of Archaeology, University of Groningen, Groningen; The Netherlands: 2003. pp. 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pasternak R. Investigation of botanical remains from Nevalı Çori, PPNB, Turkey: S short interim report. In: Damania AB, Valkoun J, Willcox G, Qualset CO, editors. The Origins of Agriculture and Crop Domestication. International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas; Aleppo, Syria: 1998. pp. 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Zeist W. The Oriental Institute Excavations at Mureybet, Syria: Preliminary report on the 1965 campaign Part III: The palaeobotany. J Near East Stud. 1970;29:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Willcox G. 2008. Nouvelles données archéobotaniques de Mureybet et la néolithisation du moyen Euphrate. Le site néolithique de Tell Mureybet (Syrie du Nord), en Hommage à Jacques Cauvin, British Archaeological Reports International Series 1843(1), ed Ibañez JJ (British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, UK), pp 103–114.

- 78.Lösch S, Grupe G, Peters J. Stable isotopes and dietary adaptations in humans and animals at pre-pottery Neolithic Nevalli Cori, southeast Anatolia. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2006;131(2):181–193. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pearson J, Grove M, Ozbek M, Hongo H. Food and social complexity at Çayönü Tepesi, southeastern Anatolia: Stable isotope evidence of differentiation in diet according to burial practice and sex in the early Neolithic. J Anthropol Archaeol. 2013;32(2):180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tanno K, Willcox G. The origins of cultivation of Cicer arietinum L. and Vicia faba L.: Early finds from north west Syria (Tell el-Kerkh, late 10th millennium BP) Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2006;15:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Caracuta V, et al. The onset of faba bean farming in the Southern Levant. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14370. doi: 10.1038/srep14370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Butler A. The small-seeded legumes: An enigmatic prehistoric resource. Acta Palaeobotanica. 1995;35(1):105–115. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stiner MC, et al. A forager-herder trade-off, from broad-spectrum hunting to sheep management at Aşıklı Höyük, Turkey. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(23):8404–8409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322723111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van Zeist W, de Roller GJ. Plant remains from Aşıklı Höyük, a pre–pottery Neolithic site in central Anatolia. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 1995;4(3):179–185. [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Zeist W. Some notes on the plant husbandry of Aşıklı Höyük. In: van Zeist W, editor. Reports on Archaeobotanical Studies in the Old World. The Groningen Institute of Archaeology, University of Groningen, Groningen; The Netherlands: 2003. pp. 115–142. [Google Scholar]

- 86.de Moulins D. 1997. Agricultural Changes at Euphrates and Steppe Sites in the Mid–8th to the 6th millennium BC, British Archaeological Reports International Series 683 (British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, UK)

- 87.Willcox G. Evidence for plant exploitation and vegetation history from three Early Neolithic pre-pottery sites on the Euphrates (Syria) Veg Hist Archaeobot. 1996;5:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weide A, et al. Using new morphological criteria to identify domesticated emmer wheat at the aceramic Neolithic site of Chogha Golan (Iran) J Archaeol Sci. 2015;57:109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arranz A, Colledge S, Ibañez JJ, Zapata L. 2013. Measuring grain size and assessing plant management during the EPPNB, results from Tell Qarassa North (South Syria). 16th Conference of the International Work Group for Palaeoethnobotany, June 17–22. 2013, Thessaloniki, Greece.

- 90.van Zeist W, Bakker-Heeres JH. Archaeobotanical studies in the Levant 1. Neolithic sites in the Damascus Basin: Aswad, Ghoraife, Ramad. Palaeohistoria. 1985;24:165–256. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kreuz A, Boenke N. The presence of two-grained einkorn at the time of the Bandkeramik culture. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2002;11(3):233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuijt I, Finlayson B. Evidence for food storage and predomestication granaries 11,000 years ago in the Jordan Valley. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(27):10966–10970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812764106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kislev ME, Hartmann A, Noy T. The plant subsistence of hunter-gatherers at Neolithic Gilgal I, Jordan Valley, Israel. In: Bar-Yosef O, Goring-Morris AN, Gopher A, editors. Gilgal: Early Neolithic Occupation in the Lower Jordan Valley, the Excavations of Tamar Noy. Oxbow Books; Oxford, UK: 2010. pp. 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hopf M. 1983. Appendix B: Jericho plant remains. Excavations at Jericho, eds Kenyon KM, Holland TA (British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, London) Vol 5, The Pottery Phases of the Tell and Other Finds, pp 576–621.

- 95.Riehl S, et al. Resilience at the transition to agriculture: The long-term landscape and resource development at the aceramic Neolithic Tell site of Chogha Golan (Iran) BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:532481. doi: 10.1155/2015/532481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Douché C, Tengberg M, Willcox G. 2013. Preliminary archaeobotanical results from Tell Aswad: An early Neolithic site in southern Syria. Excavations 2001-2007. 16th Conference of the International Work Group for Palaeoethnobotany, June 17–22, 2013, Thessaloniki, Greece.

- 97.Savard M. 2005. Epipalaeolithic to early Neolithic subsistence strategies in the northern Fertile Crescent: The archaeobotanical remains from Hallan Çemi, Demirköy, M'lefaat and Qermez Dere. PhD thesis (Univ of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK)

- 98.Neef R. Vegetation and plant husbandry. In: Nissen HJ, Muheisen M, Gebel HGK, editors. Basta 1. The Human Ecology. Ex Oriente; Berlin: 2004. pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fairbairn A, Asouti E, Near J, Martinoli D. Macro-botanical evidence for plant use at Neolithic Çatalhöyük South-central Anatolia, Turkey. Veg Hist Archaeobot. 2002;11(1-2):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 100.van Zeist W, Bakker-Heeres JAH. [1986]) Archaeobotanical studies in the Levant 3. Late-Palaeolithic Mureybet. Palaeohistoria. 1984;26:171–199. [Google Scholar]

- 101.de Moulins D. Les restes de plantes carbonisées d’El Kowm 2. In: Stordeur D, editor. El Kowm 2, une Île dans le Désert. CNRS Editions; Paris: 2000. pp. 281–300. [Google Scholar]