Abstract

The meiotically expressed Zip3 protein is found conserved from Saccharomyces cerevisiae to humans. In baker's yeast, Zip3p has been implicated in synaptonemal complex (SC) formation, while little is known about the protein's function in multicellular organisms. We report here the successful targeted gene disruption of zhp-3 (K02B12.8), the ZIP3 homolog in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Homozygous zhp-3 knockout worms show normal homologue pairing and SC formation. Also, the timing of appearance and the nuclear localization of the recombination protein Rad-51 seem normal in these animals, suggesting proper initiation of meiotic recombination by DNA double-strand breaks. However, the occurrence of univalents during diplotene indicates that C. elegans ZHP-3 protein is essential for reciprocal recombination between homologous chromosomes and thus chiasma formation. In the absence of ZHP-3, reciprocal recombination is abolished and double-strand breaks seem to be repaired via alternative pathways, leading to achiasmatic chromosomes and the occurrence of univalents during meiosis I. Green fluorescent protein-tagged C. elegans ZHP-3 forms lines between synapsed chromosomes and requires the SC for its proper localization.

Most meiotic recombination is likely to depend on recombinational repair of programmed meiotic DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are induced by Spo11p (6, 19). In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the fungus Coprinus cinereus, the mouse, and the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana, it was shown that this or an additional function of Spo11p is also required for the formation of the synaptonemal complex (SC), the proteinaceous structure that intimately links homologous chromosomes in meiotic prophase (2, 17, 25, 28, 34). C. elegans and Drosophila melanogaster are different in that Spo11p is dispensable for the initiation of SC formation (12, 26). For the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, it was proposed that synapsis initiates at DSB sites (9), specifically those which are destined to become crossovers (1, 18). The protein Zip3 would mark these sites and recruit Zip2 and Zip1, the latter being the major component of the SC's central region (1, 16).

In S. cerevisiae, a null mutation in ZIP3 leads to a two- to threefold reduction in crossovers (1). Moreover, DSBs accumulate in this mutant, indicating a defect in the normal progression of recombination (7). ZIP3 is a member of the group of ZMM genes, which all confer similar mutant phenotypes. The ZMM genes have been implicated in the progression of meiosis from crossover-destined DSBs to subsequent steps (single-end invasion, double Holliday junction) on the way to crossing over and SC nucleation, possibly by coordinating the biochemical processes with the formation of underlying chromosome structures (7).

A C. elegans protein homologous to Zip3p (Cst9p), K02B12.8p (www.wormbase.org), was assigned a meiotic function by producing a weak Him phenotype in a large-scale RNA interference (RNAi) screen (15). Moreover, its expression was found to be enhanced in the gonad (32). However, the function of this protein must be different from the one proposed for yeast Zip3p in promoting the assembly of the SC at DSBs, since in C. elegans SC formation is independent of DSBs (see above). We thus set out to study the meiotic function of K02B12.8p. To this aim, cosuppression worm lines and a line with a gene disruption were generated, and the effect of the depletion of K02B12.8p on meiosis was studied. The gene disruption was produced by a novel homologous targeting approach (5). We also investigated the subcellular distribution of K02B12.8p in the wild type and several meiotic mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Worm strains and culture conditions.

The wild-type (N2 Bristol), DP38 unc-119(ed3), and AV106 spo-11(ok79) (12) strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minn.). Worms were grown on NGM plates with Escherichia coli OP50 (8).

Protein depletion.

Expression of K02B12.8 was inhibited by transgene-mediated cosuppression (13). In short, a PCR product comprising 1.5 kb of 5′ regulatory sequence and the first two exons was coinjected with the rol-6(su1006) marker. The PCR product was generated with primers MJ581 (5′-TGG ACG AAA TTT ACG AGG AAC AGG CAT-3′) and MJ584 (5′-CTA GCG GTG AGA CCA TAT TAA ATG TTG A-3′). Offspring expressing the roller phenotype were selected, and a line showing a meiotic defect was established.

The HIM-3 and SYP-1 proteins were depleted by double-stranded RNAi. For him-3 RNAi, a PCR fragment was amplified out of cDNA of N2 worms with the primers 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGG CGG CCG CGG CGA CGA AAG AGC AGA TTG-3′ and 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGC GGC CGC TCT TCT TCG TAA TGC CCT GAC-3′, which contain the targeted sequence flanked by the T7 promoter (italic sequence). For syp-1 RNAi an 800-bp fragment was amplified from genomic DNA with the primers 5′-ACC AGT TGA TGA CCA ATC GTC AGG-3′ and 5′-GCG AAC GGC TTG CTT CGA ATT GAA-3′. The double-stranded RNA was prepared with a Promega (Madison, Wis.) in vitro transcription kit. HIM-3 double-stranded RNA was injected (≈200 ng/μl) into the gonads or intestines of young adults as described (14), and SYP-1 double-stranded RNA was delivered by feeding as described (37).

Gene disruption.

The construct for the disruption of the K02B12.8 open reading frame was generated by inserting two genomic regions (fragment 1 and fragment 2 in Fig. 1a) of about 1.25 kb each of the K02B12.8 gene into pPD#MM016 (24), a Bluescript vector containing the unc-119 rescuing locus (of about 5.7 kb) cloned into the XbaI and HindIII sites. Fragment I was amplified with primers 5′-TCC CCG CGG CTC GTT AGG TAA AGG CGA CAA-3′ and 5′-ATA AGA ATG CGG CCG CAT GAA GAA TCC ATC CGG TGG T-3′ and cloned into the SacII and NotI sites. Fragment 2 was amplified with 5′-CCC AAG CTT GAA ATG CGC GAA AGC AGG TAC-3′ and 5′-CGG GGT ACC TGA ACA CGT ATC GCA GAA CCG-3′ and cloned into the KpnI and HindIII sites. Prior to transformation, the disruption construct was digested with SpeI and ScaI (Fig. 1a).

FIG. 1.

(a) Map of the K02B12.8 locus on chromosome I. Fragment 1, encompassing the promoter and part of the first exon, and fragment 2, stretching from exon 1 to exon 7, were cloned into plasmid PD#MM016 containing the unc-119 rescuing locus. After cleavage with ScaI and SpeI, the disruption cassette was used for homologous integration. PP1 and PP2 denote the primer pairs used for diagnostic PCR. (b) Diagnostic PCR. PP2 primes in the unc-119 sequence in the targeting cassette and in the K02B12.8 locus outside the fragment that was cloned into the targeting cassette and amplifies a fragment of about 1.9 kb in the case of homologous integration but not in untransformed worms. PP1 primes in the K02B12.8 locus and amplifies a product of 1.8 kb from the undisrupted locus. In the case of the homologously tagged mutant, the PCR conditions applied did not allow the amplification of the expected 7-kb product. (c) Reverse transcription-PCR on the mutant (jf-61) to prove the absence of the K02B12.8 transcript. PCR on cDNA of jf-61 did not result in a detectable band of the expected size (lanes 1 and 2); even a nested PCR of those samples did not amplify a transcript (lanes 6 and 7). Lanes 3 and 8 prove that the zhp-3 primer pairs do amplify the expected bands of 341 and 276 bp from wild-type cDNA. Primer pairs from a spo-11 cDNA do amplify bands of the expected sizes (501 and 296 bp) from both the wild type cDNA pool (lanes 4 and 9) and the mutant cDNA pool (lanes 5 and 10).

unc-119(ed3) mutant worms were transformed with the above construct by microparticle bombardment (5, 31) with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) biolistic particle gun. In 25 transformation experiments, ≈100 lines carrying the unc-119 gene were obtained, of which 6 segregated dead embryos. These were scored for the zhp-3 mutant phenotype (see Results). Candidate mutant lines were subjected to diagnostic PCR. Worms were lysed in lysis buffer (38); proteinase K was inactivated by incubation at 95°C. An aliquot of 0.5 μl of the lysed material was added to the PCRs. Primer pairs were designed to amplify a segment of wild-type zhp-3 (PP1, 5′-CGT TTT TCC GGC AAA TTC AGC-3′ and 5′-TAC GGT GAC AAT CAC ACG CTA-3′) and to amplify a segment when the disruption cassette was integrated (PP2, 5′-GCC GGA AAT TTT CAG TTC TGG-3′ and 5′-TAC GGT GAC AAT CAC ACG CTA-3′). One mutant line, UV1 zhp3(jf61), was recovered, for which PCR with PP2 produced a product of the expected size and none with PP1 (Fig. 1b). The PCR fragment of PP2 was sequenced, and the expected sequence for a homologous integration, consisting of unc-119 adjacent to K02B12.8, was obtained.

Reverse transcription-PCR.

cDNA was generated from about 100 mutant or wild-type worms, as described (22). For the amplification of the zhp-3 message, the following primer pairs were used: outer primers 5′-CCATCGCGTAATAATATGGGAG-3′ and 5′-AATGAAGCTCCGACCATTGATC-3′; nested (inner) primers 5′-CTACGGCAAATCAGACAATCATG-3′ and 5′-GGTTTCCTTTGTGCGAGGTATC-3′. For the spo-11 message (as a control for the quality of cDNA), the following primer pairs were used: outer primers 5′-GCACTGTCTTCACCAAGTTTATG-3′ and 5′-GATTTCAATACCATGCGGATCAG-3′; nested (inner) primers 5′-GTGAGCTTTTGAATGAAAGTCGG-3′ and 5′-CATTTCGAGTTGCAATATCCGG-3′. Amplification with the outer primer pair resulted in a 501-bp product and with the nested pair in a 296-bp product.

Construction and expression of a GFP-tagged K02B12.8p.

The K02B12.8::green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion construct was made by inserting the cDNA at the N terminus of the GFP open reading frame in a modified pie-1 expression vector (see below) into a BamHI site. The cDNA was amplified with primers 5′-CGG GAT CCG ATT TTG TTC ACT GTA ATA AAT GC-3′ and 5′-CGG GAT CCA TCG GCG GGT CCA ATG AAG CTC CG-3′. Modification of the pie-1 expression vector was performed by the following steps with pJH4.52 (a gift from Geraldine Seydoux, described in reference 31) as a starting vector: Both the his-2B open reading frame (F54E11.4) and the BamHI site at the 3′ end of his-2B were deleted. The unc-119 rescuing fragment (24) was inserted into the unique SacII site.

A low-copy-number transformed line was generated by injection of the K02B12.8::GFP reporter construct along with a large excess of a single-stranded oligonucleotide into unc-119(ed3) mutants (27). Transformed hermaphrodites showing a wild-type phenotype were singled out and scored for stable expression of the K02B12.8::GFP reporter construct.

Cytological preparation.

Squash preparations of hermaphrodite gonads were prepared as reported previously (30) and stored in the refrigerator until used for chromosome staining with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or two-color fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

To generate a FISH probe for the right arm of chromosome V, a 132-bp fragment from the coding region of the 5S rDNA repeat was PCR labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP as described previously (30). Pooled cosmids (C53D5, R119, C07F11, and F53G12, provided by A. Coulson, Sanger Center, Hinxton, United Kingdom) as a probe for the left end of the chromosome I were labeled with biotin by nick translation with the BioNick labeling system (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) as recommended by the manufacturer. Labeled probe DNA was denatured and hybridized to denatured target sequences on cytological slides following the protocol described in detail by Pasierbek et al. (30). Hybridized digoxigenin-labeled probes were detected with rhodamine-conjugated antidigoxigenin and biotin-labeled DNA with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated extravidin by red and green emission, respectively, upon excitation in the fluorescence microscope.

For the spreading of synaptonemal complexes (SCs), we followed the protocol of Pasierbek et al. (30). In brief, meiocytes were released from gonads by squashing on a slide and exposed to a detergent (1% Lipsol; L.I.P. Ltd., Shipley, United Kingdom) to cause the lysis of nuclei and the spreading of nuclear contents. Spreading was stopped by the addition of fixative (4% paraformaldehyde and 3.4% sucrose in distilled water), and the slides were dried in air.

Immunohistochemistry.

Standard cytological squash preparations or spread preparations fixed with formaldehyde (30) were postfixed in a series of methanol, methanol-acetone (1:1), and acetone for 5 min each at −20°C and immediately transferred to 1× phosphate-buffered saline and washed three times for 5 min in this buffer. Primary antibodies were applied for ≈12 h at 4°C in a humid chamber. After repeated washes in 1× phosphate-buffered saline, secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature. For details, see reference 30.

RESULTS

K02B12.8, a homolog of budding yeast Zip3p.

A BLAST search of the C. elegans genome performed with budding yeast Zip3p (Cst9p) protein revealed the translation product of open reading frame K02B12.8 as the only C. elegans homolog of yeast Zip3p (see also www.wormbase.org). Related proteins can also be found in Drosophila melanogaster and humans (Fig. 2). The translation product of K02B12.8 is 387 amino acids in length, while Zip3 is a protein of 482 residues. The two proteins are 18.5% identical to each other. Moreover, Zip3p and K02B12.8p have a similar domain structure, with an N-terminal RING finger, followed at a 50-amino-acid distance by a coiled region, and a C-terminal S-rich region. A major difference is that Zip3p has an approximately 50-amino-acid extension at the N terminus which might suggest a different function of the protein. However, given their similarities with respect to meiotic expression (https://www.incyte.com/proteome/databases.jsp) and association with pairing chromosomes (see below), the product of K02B12.8 will be referred to as C. elegans ZHP-3 (Zip3-homologous protein).

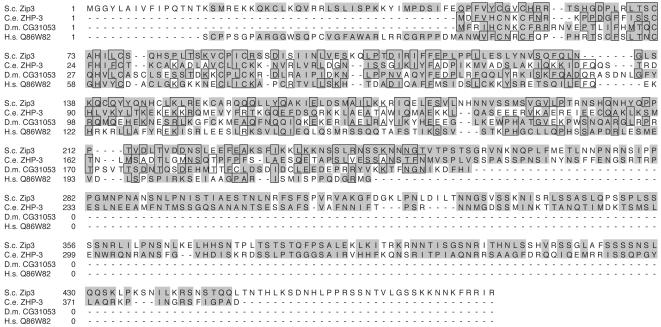

FIG. 2.

Protein sequences of S. cerevisiae (S.c.) Zip3p, C. elegans (C.e.) ZHP-3, D. melanogaster (D.m.) predicted protein CG31053, and the putative translation product of human (H.s.) expressed sequence tag Q86W82 are compared. Identical amino acids are boxed, while similar ones are shaded in grey. Note that both the Drosophila and human sequences might be missing significant parts from their C termini.

Depletion of ZHP-3 protein and disruption of zhp-3.

K02B12.8p (C. elegans ZHP-3) was originally assigned a meiotic function by RNAi producing a Him phenotype (15). RNAi yielded a reproducible but not very penetrant cytological phenotype in our hands. Therefore, the consequences of ZHP-3 depletion were studied by two different approaches. First, K02B12.8p was depleted by transgene-mediated cosuppression (see Materials and Methods). Second, the zhp-3 gene was disrupted by homologous integration of a marker gene with biolistic transformation (5). To this aim, unc-119 worms were transformed with a construct containing the unc-119+ marker gene, inserted into the first exon of the zhp-3 gene, 57 bp downstream of the ATG. The insertion deleted 27 bp of exon 1 (Fig. 1). Reverse transcription-PCR showed the absence of a transcript of K02B12.8 (Fig. 1c). The mutant allele zhp-3(jf61) can therefore be regarded as a null mutation. The mutant displayed the expected meiotic phenotype (see below) and a Mendelian segregation pattern (a ratio of 1:2 homozygous mutants versus heterozygous animals within the non-Unc offspring), indicating full somatic viability.

Since gene disruption and protein depletion by cosuppression resulted in identical phenotypes, the observations made with the two approaches will be treated jointly. The data shown below are from zhp-3(jf61) animals.

Homologous pairing and SC formation in zhp-3.

Homozygous zhp-3(jf61) animals showed no apparent defect in homologous chromosome alignment, pairing, and SC formation. Immunostaining of HIM-3 (Fig. 3a) and REC-8 (Fig. 3b), both being components of axial/lateral elements of the SC (11, 30, 39), as well as of SYP-1 (Fig. 3c), a component of the central element (23), revealed linear structures in pachytene, identical to those seen in the wild type. Moreover, SYP-1 was found to localize in the gap between paired chromosomes, as visualized by DAPI (Fig. 4a). Also, the relative size and position of the pachytene zone within the gonad were not notably different between the zhp-3 mutant and the wild type, and pachytene SCs extended all along the DAPI-positive bivalents. This suggests that SC formation is normal in the zhp-3 mutant except for possible ultrastructural anomalies which might escape detection by light microscopy.

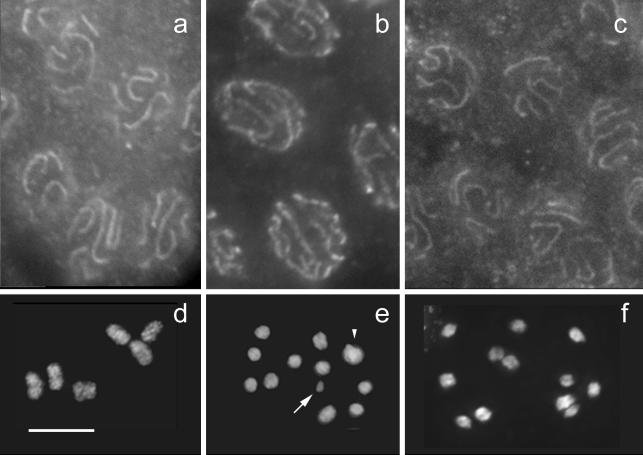

FIG. 3.

Cytological phenotype of the zhp-3 mutant. (a to c) Immunostaining of SC proteins shows the formation of an SC. The SC-associated protein HIM-3 (a), the lateral element component REC-8 (b), and the transverse filament component SYP-1 (c) form lines in pachytene nuclei of the mutant. (d to f) DAPI-stained diakineses. (d) In the wild type, six bivalents are found, whereas in (e) zhp-3(cosuppression) (arrow, transgene concatemer; arrowhead, overlapping univalents) and in (f) zhp-3(jf61) 12 univalents are present. Bar, 5 μm.

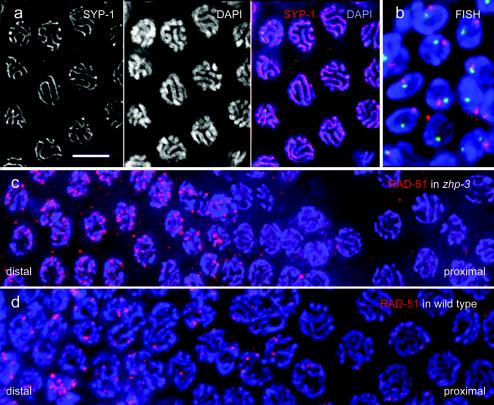

FIG. 4.

Pairing and localization of recombination protein in the mutant. (a) SYP-1 localizes to the gap between paired chromosomes as visualized by DAPI, as can be seen in the merged image. (b) FISH of the 5S rDNA (red) and a locus on chromosome I left arm (green) in pachytene nuclei of the zhp-3 mutant. The presence of a single FISH signal per nucleus for each of the two loci tested is evidence for homologous pairing. Sectors with late pachytene nuclei of gonads of (c) the zhp-3 mutant and (d) the wild type immunostained for the Rad-51 recombination protein (red). Note the larger number of Rad-51 foci and their sudden disappearance before the end of pachytene in the mutant (distal-proximal indicates the orientation of the sector shown within the gonad). Chromatin is stained blue by DAPI. Bar, 5 μm.

To confirm that the SC indeed forms between homologous chromosome regions, two chromosomal loci, one (5S rRNA) near the right end of chromosome V, and the other near the left end of chromosome I, were delineated by FISH, and the nuclear distribution of the homologous FISH signals was scored. In 92 of 93 pachytene nuclei, both pairs of homologous FISH signals were closely associated or fused into one, indicating that synapsis took place between homologous chromosomes (Fig. 4b). While pairing was normal in the mutant, there was no chiasma formation at diplotene and diakinesis. Instead of six bivalents, 12 well-condensed univalents were present (Fig. 3d to f) in a total of 153 diakineses scored.

Localization of RAD-51 in zhp-3.

To determine if meiotic DSBs are induced in the mutant, we performed immunostaining of the recombination protein RAD-51. Rad-51 is believed to be an indicator of the presence of DSBs because it forms foci in wild-type C. elegans meiosis but not in the spo-11 mutant (4), which is unable to initiate DSBs (12). In the zhp-3 mutant and in the wild type, RAD-51 foci appeared in similar regions within the gonad (Fig. 5). Although in the mutant the RAD-51-positive region seemed to be somewhat extended, RAD-51 disappeared well before the end of the pachytene zone. The disappearance of RAD-51 foci was not gradual but sudden and simultaneous (Fig. 4c). The number of foci per nucleus was more than twice as high in the mutant (5.2 ± 3.4 [n = 170], 5.9 ± 3.2 [n = 101], 6.6 ± 3.5 [n = 200]; three individuals) than in wild type (2.2 ± 1.2 [n = 68], 2.6 ± 1.5 [n = 147], 2.7 ± 1.5 [n = 130], 2.9 ± 1.8 [n = 122]; four individuals) (Fig. 4c and d). The disappearance of RAD-51 foci suggests either that, in the mutant, RAD-51 detaches from unrepaired DSBs or that DSBs are repaired by a pathway that does not lead to chiasmata. As the relatively high viability of offspring is not compatible with the persistence of unrepaired DNA (see below and Discussion), it must be assumed that DSBs are repaired at a high rate by noncrossover processes.

FIG. 5.

Position and extent of the RAD-51-positive region (black bars) in the gonads (shaded bars) of zhp-3 and wild-type animals. For each, 10 gonads were measured from the distal tip cell (DTC) to the end of continuous cell rows (roughly coinciding with the end of the pachytene zone) and normalized, and the borders of the transition zone and the RAD-51-positive region were entered. This region strikes on visual inspection by the abundance of RAD-51 foci. In quantitative terms it is defined as the zone in which a majority of nuclei have more than two prominent spots by RAD-51 immunostaining. The open and solid arrowheads indicate the distal and proximal borders of the transition zone, respectively (for a classification of meiotic stages in the gonad, see reference 23).

Reduced recombination and fertility of zhp-3 animals.

zhp-3(jf61) hermaphrodites produced a reduced number of viable offspring. Of 522 embryos laid by homozygous zhp-3(jf61) mothers, 22 hatched, but most of them died prematurely. Nine embryos (≈2%) developed beyond the L3 stage; two out of the nine survivors were males. This is a relatively high rate of survival considering that only offspring which received a fairly normal chromosome complement by random segregation of all homologous univalents in both male and female meiosis can survive (see Discussion). However, the ≈2% viable offspring could be explained if zhp-3(jf61) animals produced normal sperm. To test if both female and male meiosis was equally affected by the mutation, surviving mutant hermaphrodites were crossed to wild-type males. The offspring from these crosses showed higher viability (8 out of 168 eggs laid, 4.7%) than by selfing, indicating that viability improved significantly (P < 0.001, χ2 test) by the contribution of wild-type sperm and thus that the sperm of zhp-3(jf61) must also be affected.

Genetic recombination was measured in an interval which is ≈38 centimorgans in the wild type (20). Males of genotype zhp-3(jf61)/+ were crossed to a mixture of dpy-3 unc-3/dpy-3 unc-3; zhp-3(jf61)/zhp-3(jf61), and dpy-3 unc-3/dpy-3 unc-3; zhp-3(jf61)/+ hermaphrodites. Phenotypically non-Dpy non-Unc F1 animals were singled, and the brood was scored at 20°C. zhp-3(jf61) homozygotes were identified by the low viability of the brood. The viable F2 produced by zhp-3(jf61)/zhp-3(jf61); dpy-3 unc-3/++ animals consisted of 67 hermaphrodites and 26 males. Almost all of the progeny displayed the phenotype indicative of the absence of crossing over, Dpy Unc or wild type. Only one of the progeny had a Dpy non-Unc and one an Unc non-Dpy phenotype; the Dpy non-Unc animal arrested in its development, most likely due to aneuploidy. We therefore conclude that the absence of chiasmata in this mutant is due to the absence of crossover recombination rather than instability of chiasmata.

Cytological localization of ZHP-3 protein.

We generated a fully viable transgenic line expressing GFP-tagged ZHP-3. The transgene was confirmed to be functional because transformation of mutant animals with this construct resulted in the rescue of embryonic lethality (data not shown). Immunodetection of ZHP-3::GFP showed a dot-like nuclear distribution in transition zone nuclei (Fig. 6a) (for a classification of meiotic stages in the gonad, see references 23 and 29). Major ZHP-3::GFP spots seemed to colocalize with early SYP-1 structures at this stage (Fig. 6a). In pachytene nuclei, ZHP-3 became organized as lines or linear arrays of dots which occupied the space between synapsed chromosomes (23) (Fig. 6b). Since the absence of the ZHP-3 protein does not affect SC formation, it is evident that ZHP-3, in spite of its localization in the bivalent regions where the SC also resides, is not an essential component of this structure. In diakinesis, ZHP-3 was still present in cells but no longer associated with chromosomes (Fig. 6c).

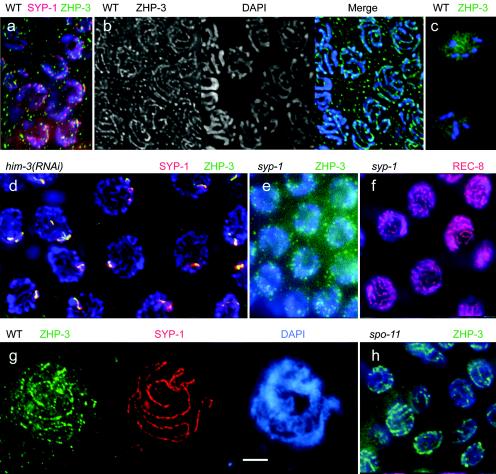

FIG. 6.

Immunostaining of GFP-tagged ZHP-3 (green) in the wild type and various mutants. In the wild type in nuclei of the transition zone (a), ZHP-3 forms spots (with major spots colocalizing with SYP-1, shown in red), while in pachytene nuclei (b) it appears as lines. In diakinesis (c) it is dispersed between the chromosomes. (d) Upon RNAi depletion of the SC-associated protein HIM-3, the linear organization of ZHP-3 is lost, and it colocalizes with the synapsis protein SYP-1 to one to several spots (orange, resulting from the mixing of green ZHP-3 and red SYP-1 markers). (e) No ZHP-3 lines are present in nuclei devoid of SYP-1, whereas unsynapsed axial elements in SYP-1-depleted nuclei are delineated by staining of REC-8 (f, red). (g) In spread SC preparations of the wild type, ZHP-3 (green) colocalizes with SYP-1 (red) on SCs, but the ZHP-3 pattern is discontinuous and faint, possibly due to an only weak association of ZHP-3 with SCs. Chromatin is stained blue by DAPI in all pictures. (h) In a spo-11 mutant, the pachytene linear organization of ZHP-3 is not affected. Bars, 5 μm.

We next wanted to determine which structures are required for ZHP-3 localization along pachytene chromosomes. To this aim, we studied the distribution of ZHP-3-GFP in nuclei which were depleted of HIM-3 by RNAi. HIM-3 is a homologue of budding yeast Hop1p. It is associated with the lateral elements of the SC, and in its absence presynaptic alignment and synapsis do not take place (11, 39). In him-3(RNAi) nuclei no linear ZHP-3 structures but one to several spots were detected (Fig. 6d). These spots possibly delineate sites of residual synapsis (caused by the incomplete depletion of HIM-3 by RNAi) or aggregates of unutilized SC material (polycomplexes), since they also contained the central element protein SYP-1 (Fig. 6d).

To confirm that C. elegans ZHP-3 localizes only to bivalents with mature SCs, we depleted gonads of SYP-1 by RNAi. SYP-1 is homologous to the S. cerevisiae transversal filament protein Zip1p, and in its absence the axial elements of the SC are not connected (23). In SYP-1-depleted nuclei of the pachytene zone, ZHP-3 did not form lines (Fig. 6e), whereas REC-8 delineated the unsynapsed chromosome axes (Fig. 6f). This demonstrates that ZHP-3 depends on SYP-1 for wild-type localization and confirms that it fails to associate with unsynapsed axes. To further test the localization of ZHP-3 to the synapsed portions of homologous chromosomes, we prepared nuclei by an SC spreading technique. Immunostaining of ZHP-3 produced dotted arrays along the SYP-1 lines (Fig. 6g). In no case did we observe ZHP-3 signals outside SYP-1-positive lines. This confirms that ZHP-3 occupies only the synapsed portions of bivalents.

To study if the chromosomal localization of ZHP-3 depends on the creation of meiotic DSBs, the C. elegans zhp-3::GFP line was crossed to a spo-11 mutant and selected for homozygous spo-11 individuals expressing ZHP-3::GFP. In C. elegans, spo-11 mutants do synapse their chromosomes but fail to induce DSBs (12). spo-11; zhp-3::GFP individuals exhibited linear ZHP-3 structures (Fig. 6h) indistinguishable from those of the wild type, indicating that ZHP-3 expression and localization to SCs do not depend on DSBs.

DISCUSSION

Disruption of zhp-3 by homologous targeting.

Here we report the first successful application of a novel technique (5) with homologous integration to study the function of a previously uncharacterized gene in C. elegans. While we did not attempt to quantitate the efficiency of the technique, we can state that out of 25 biolistic transformation experiments, ≈100 lines carrying the unc-119 gene were obtained, of which a single line could be verified as carrying the desired gene disruption. In our experiment, the length of homology available for homologous integration (2.5 kb) was notably smaller than the 4 to 6 kb described by Berezikov et al. (5). It thus appears as if knockout lines could be generated with a reasonable effort, representing a good alternative to current gene silencing and RNAi techniques.

C. elegans ZHP-3 localizes along synapsed bivalents but does not function in synapsis.

In the budding yeast (and most other organisms), SC formation depends on the presence of meiotic DSBs. The transversal filaments of the SC connect homologous chromosomes all along their length in pachytene. Starting at a single or a few sites of a prealigned homologous chromosome pair, the transverse filaments establish the connection from which the SC progresses in a zipper-like fashion. In the budding yeast, Zip3p and another protein, Zip2p, were shown to interact and overlap with recombination proteins and hence proposed to localize to sites of meiotic interhomologue recombination (1, 9). Interhomologue recombination occurs by two alternative pathways, conversion and crossing over, upon which is decided soon after the formation of DSBs (3, 7). Since Zip3p foci appear to show interference (as do crossovers) (16) and since the effects of spo-11 mutations correlate better with effects on crossover frequencies than with effects on total DSB levels (18), it seems likely that Zip3p localizes to the crossover-destined subset of recombination intermediates. At these sites, Zip3p and Zip2p would lead to the assembly of Zip1p, the major component of transverse filaments (35) and zipping up of the SC. In the absence of Zip3p, synapsis was found to be substantially delayed and incomplete. Taking all the evidence together, it was proposed that Zip3p is a component of recombination nodules and serves to link synapsis to meiotic recombination (1, 7).

In spite of its sequence homology, C. elegans ZHP-3 cannot share the role proposed for budding yeast Zip3p because initiation of recombination is not required for SC formation in C. elegans (12). A homologue of yeast Zip2p, one of Zip3p's putative partners, has not been detected in the worm genome, which supports the idea that C. elegans ZHP-3 works in a different context. Furthermore, as we show here, the localization of the SC components HIM-3, REC-8, and SYP-1 is normal in zhp-3(jf61) nuclei, which indicates that wild-type SC formation does not require ZHP-3. Finally, the distribution of C. elegans ZHP-3 all along synapsed chromosome axes suggests that its localization to chromosomes requires rather than allows synapsis.

C. elegans ZHP-3 has the interesting property of being either part of the SC structure or associated with it without being essential for its formation. C. elegans ZHP-3 has no function in homology recognition either, since we showed that in the mutant the SC was formed between homologous chromosomes. It is noteworthy, however, that proper localization of ZHP-3 is dependent on the formation of a mature SC with incorporated central elements, therefore allowing ZHP-3 to reside at the SC. Recently, it was shown that the central element of the SC is essential for proper completion of recombination in C. elegans (10). ZHP-3, by depending on the presence of the central element, might thereby play an essential role in this process.

ZHP-3 is essential for crossing over and chiasma formation.

The recombination protein RAD-51 is believed to serve as a marker for DSBs. It transiently localizes as spots to chromatin in wild-type meiotic prophase nuclei but fails to do so in spo-11 meiocytes, where no DSBs are generated. In strains where DSB repair is impaired, RAD-51 foci show extended persistence (4, 10). In the zhp-3 mutant, the dynamics of formation and disappearance of RAD-51 foci was not dramatically different from that of the wild type, but DSBs were not repaired in a way that produced chiasmata.

It might be argued that RAD-51 disappeared from chromatin, while DSBs remained unrepaired. This possibility is invalidated by the relatively high viability of offspring (≈2%) by zhp-3 compared to rad-51 null mutants (which produce zero viable offspring due to inefficient repair of DSBs [4]). It suggests that no additional factor contributes to lethality other than the disturbed segregation of univalents and that DSBs are efficiently repaired in the mutant.

Since in a total of 93 progeny only one putative recombinant was found (see Results), we can rule out the possibility that crossovers were formed but not maintained. Therefore, it can be assumed that DSBs were repaired by a noncrossover mechanism (gene conversion, sister chromatid recombination, or nonhomologous end joining). The experimental system does not allow us to distinguish among these possibilities. It is, however, tempting to speculate that C. elegans ZHP-3 may have a function in the SC-dependent processing of DSBs and their conversion into chiasmata. It might well play a role analogous to budding yeast Red1 and Hop1 by preventing sister chromatid recombination (21, 33, 36), which was recently also proposed for C. elegans HIM-3 (11, 33, 36). Thus, the function of ZHP-3 and its yeast paralogue, although working within very different settings, could be similar, namely, communication between recombination sites (DSBs) and SC components. While in budding yeast Zip3 seems to recruit SC initiation factors to the sites of DSBs (1), the flow of information could be in the opposite direction in C. elegans. Here ZHP-3 could sense the presence of the SC and direct DSB repair toward an SC-dependent (crossover) pathway.

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful to Ronald Plasterk and Eugene Berezikov (Netherlands Cancer Institute) for a detailed instruction on targeted knockout in C. elegans prior to publication. We thank Anton Gartner and Adriana La Volpe for Rad-51 antibodies and Anne Villeneuve, Monique Zetka, and Geraldine Seydoux for the SYP-1 and HIM-3 antibodies and for strains and plasmid pJH 4.52, respectively. We also wish to thank Maria Novatchkova (IMP, Vienna) for help with computer-based database searches, Martin Melcher for RNAi data, and Bonnie Wohlrab for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants P14642 and P16458 from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal, S., and G. S. Roeder. 2000. Zip3 provides a link between recombination enzymes and synaptonemal complex proteins. Cell 102:245-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alani, E., R. Padmore, and N. Kleckner. 1990. Analysis of wild-type and rad50 mutants of yeast suggests an intimate relationship between meiotic chromosome synapsis and recombination. Cell 61:419-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allers, T., and M. Lichten. 2001. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell 106:47-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alpi, A., P. Pasierbek, A. Gartner, and J. Loidl. 2003. Genetic and cytological characterization of the recombination protein Rad-51 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chromosoma 112:6-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berezikov, E., C. I. Bargmann, and R. H. A. Plasterk. 2004. Homologous gene targeting in Caenorhabditis elegans by biolistic transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:e40. [Online.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergerat, A., B. de Massy, D. Gadelle, P.-C. Varoutas, A. Nicolas, and P. Forterre. 1997. An atypical topoisomerase II from archaea with implications for meiotic recombination. Nature 386:414-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Börner, G. V., N. Kleckner, and N. Hunter. 2004. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell 117:29-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner, S. 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77:71-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua, P. R., and G. S. Roeder. 1998. Zip2, a meiosis-specific protein required for the initiation of chromosome synapsis. Cell 93:349-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colaiácovo, M. P., A. J. MacQueen, E. Martinez-Perez, K. McDonald, A. Adamo, A. La Volpe, and A. M. Villeneuve. 2003. Synaptonemal complex assembly in C. elegans is dispensable for loading strand-exchange proteins but critical for proper completion of recombination. Dev. Cell 5:463-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couteau, F., K. Nabeshima, A. Villeneuve, and M. Zetka. 2004. A component of C. elegans meiotic chromosome axes at the interface of homolog alignment, synapsis, nuclear reorganization, and recombination. Curr. Biol. 14:585-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dernburg, A. F., K. McDonald, G. Moulder, R. Barstead, M. Dresser, and A. M. Villeneuve. 1998. Meiotic recombination in C. elegans initiates by a conserved mechanism and is dispensable for homologous chromosome synapsis. Cell 94:387-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dernburg, A. F., J. Zalevsky, M. P. Colaiácovo, and A. M. Villeneuve. 2000. Transgene-mediated cosuppression in the C. elegans germ line. Genes Dev. 14:1578-1583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fire, A., S. Xu, M. K. Montgomery, S. A. Kostas, S. E. Driver, and C. C. Mello. 1998. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391:806-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser, A. G., R. S. Kamath, P. Zipperlein, M. Martinez-Campos, M. Sohrmann, and J. Ahringer. 2000. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature 408:325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung, J. C., B. Rockmill, M. Odell, and G. S. Roeder. 2004. Imposition of crossover interference through the nonrandom distribution of synapsis initiation complexes. Cell 116:795-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grelon, M., D. Vezon, G. Gendrot, and G. Pelletier. 2001. AtSPO11-1 is necessary for efficient meiotic recombination in plants. EMBO J. 20:589-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson, K. A., and S. Keeney. 2004. Tying synaptonemal complex initiation to the formation and programmed repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4519-4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keeney, S., C. N. Giroux, and N. Kleckner. 1997. Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell 88:375-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly, K. O., A. F. Dernburg, G. M. Stanfield, and A. M. Villeneuve. 2000. Caenorhabditis elegans msh-5 is required for both normal and radiation-induced meiotic crossing over but not for completion of meiosis. Genetics 156:617-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleckner, N. 1996. Meiosis: how could it work? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:8167-8174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krause, M. 1995. Transcription and translation, p. 483-512. In H. F. Epstein and D. C. Shakes (ed.), Caenorhabditis elegans: modern biological analysis of an organism, vol. 48. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacQueen, A. J., M. P. Colaiácovo, K. McDonald, and A. M. Villeneuve. 2002. Synapsis-dependent and -independent mechanisms stabilize homolog pairing during meiotic prophase in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 16:2428-2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maduro, M., and D. Pilgrim. 1995. Identification and cloning of unc-119, a gene expressed in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. Genetics 141:977-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahadevaiah, S. K., J. M. A. Turner, F. Baudat, E. P. Rogakou, P. De Boer, J. Blanco-Rodríguez, M. Jasin, S. Keeney, W. M. Bonner, and P. S. Burgoyne. 2001. Recombinational DNA double-strand breaks in mice precede synapsis. Nat. Genet. 27:271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKim, K. S., and A. Hayashi-Hagihara. 1998. mei-W68 in Drosophila melanogaster encodes a Spo11 homolog: evidence that the mechanism for initiating meiotic recombination is conserved. Genes Dev. 12:2932-2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mello, C., and A. Fire. 1995. DNA transformation, p. 451-482. In H. F. Epstein and D. C. Shakes (ed.), Caenorhabditis elegans: modern biological analysis of an organism, vol. 48. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merino, S. T., W. J. Cummings, S. N. Acharya, and M. E. Zolan. 2000. Replication-dependent early meiotic requirement for spo11 and rad50. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10477-10482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasierbek, P., M. Födermayr, V. Jantsch, M. Jantsch, D. Schweizer, and J. Loidl. 2003. The C. elegans SCC-3 homologue is required for meiotic synapsis and for proper chromosome disjunction in mitosis and meiosis. Exp. Cell Res. 289:245-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasierbek, P., M. Jantsch, M. Melcher, A. Schleiffer, D. Schweizer, and J. Loidl. 2001. A Caenorhabditis elegans cohesion protein with functions in meiotic chromosome pairing and disjunction. Genes Dev. 15:1349-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Praitis, V., E. Casey, D. Collar, and J. Austin. 2001. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 157:1217-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinke, V., H. E. Smith, J. Nance, J. Wang, C. Van Doren, R. Begley, S. J. M. Jones, E. B. Davis, S. Scherer, S. Ward, and S. K. Kim. 2000. A global profile of germline gene expression in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 6:605-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roeder, G. S. 1997. Meiotic chromosomes: it takes two to tango. Genes Dev. 11:2600-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romanienko, P. J., and R. D. Camerini-Otero. 2000. The mouse Spo11 gene is required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Mol. Cell 6:975-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sym, M., J. Engebrecht, and G. S. Roeder. 1993. ZIP1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 72:365-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson, D. A., and F. W. Stahl. 1999. Genetic control of recombination partner preference in yeast meiosis: Isolation and characterization of mutants elevated for meiotic unequal sister-chromatid recombination. Genetics 153:621-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timmons, L., and A. Fire. 1998. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature 395:854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams, B. D. 1995. Genetic mapping with polymorphic sequence-tagged sites, p. 81-96. In H. F. Epstein and D. C. Shakes (ed.), Caenorhabditis elegans: modern biological analysis of an organism, vol. 48. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zetka, M. C., I. Kawasaki, S. Strome, and F. Muller. 1999. Synapsis and chiasma formation in Caenorhabditis elegans require HIM-3, a meiotic chromosome core component that functions in chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 13:2258-2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]