Abstract

Heterogeneity in outcome reporting limits identification of gold-standard treatments for Hirschsprung’s Disease(HD) and gastroschisis. This review aimed to identify which outcomes are currently investigated in HD and gastroschisis research so as to counter this heterogeneity through informing development of a core outcome set(COS). Two systematic reviews were conducted. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they compared surgical interventions for primary treatment of HD in review one, and gastroschisis in review two. Studies available only as abstracts were excluded from analysis of reporting transparency. Thirty-five HD studies were eligible for inclusion in the review, and 74 unique outcomes were investigated. The most commonly investigated was faecal incontinence (32 studies, 91%). Seven of the 28 assessed studies (25%) met all criteria for transparent outcome reporting. Thirty gastroschisis studies were eligible for inclusion in the review, and 62 unique outcomes were investigated. The most commonly investigated was length of stay (24 studies, 80%). None of the assessed studies met all criteria for transparent outcome reporting. This review demonstrates that heterogeneity in outcome reporting and a significant risk of reporting bias exist in HD and gastroschisis research. Development of a COS could counter these problems, and the outcome lists developed from this review could be used in that process.

Systematic reviews comparing key treatments for both Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis have failed to identify gold standard treatments for either condition1,2,3,4. This is likely to be due to a combination of reasons including the small size and retrospective nature of many of the primary studies, but also inadequate data reporting, heterogeneity in outcome definition, and use of surrogate markers of success instead of clinically relevant outcomes1. In a recent study reviewing 283 randomly selected Cochrane systematic reviews covering a range of conditions and interventions, Kirkham et al. demonstrated that over 30% of the randomised controlled trials included in these systematic reviews either did not publish at all, or did not fully publish the results for their identified primary outcomes5. This suggests that the potential for reporting bias is widespread within the medical literature.

Potential reporting bias and potential lack of patient relevance, combined with the fact that chance and confounding are likely to be impacting the results of many Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis studies6 limits the ability of the existing evidence base to help guide clinical management. It has been proposed that the development of core outcome sets for key conditions, combined with increased collaboration can help address these problems1,7,8.

Core outcome sets are groups of outcomes that have been identified through a systematic review and Delphi process, and ratified by key stakeholders as the outcomes that should at a minimum be reported in every study of that condition8. They are a tool that has been championed by the COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative as a method for reducing reporting bias, increasing patient relevance of research, and improving meta-analysis. Their use in other conditions has been shown to significantly improve the quality of research being conducted9, thereby enabling more evidence-based clinical practice.

Prior to developing a core outcome set it is essential to know which outcomes are currently reported in the published literature, and the quality of their reporting. The aims of this work were therefore to conduct two systematic reviews, in order to identify which outcomes are currently reported in studies comparing surgical interventions for Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis, determine the completeness of data reporting, and make an empirical assessment of the likelihood of reporting bias in included studies.

Methods

Two systematic reviews were conducted according to pre-specified protocols that were prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42015024996 and CRD42015025026). Multiple search strategies were used to identify relevant articles from Medline and EMBASE. Search terms were identified from database thesauri and free text relating to either Hirschsprung’s Disease and operative interventions for Hirschsprung’s Disease, or gastroschisis and interventions for gastroschisis, and combined using Boolean operators. Searches were limited to papers published in or after 2010 in order to ensure that identified outcomes were contemporaneous. Full search strategies are provided in supplementary files one and two.

Study selection and data extraction

Identified titles were assessed for inclusion by three investigators acting independently (BA and AI for Hirschsprung’s Disease, and BA and NP for gastroschisis). Any conflicts were resolved by discussion, with recourse to a fourth investigator (MK) where necessary. Data from included articles were extracted independently for each review by the same two investigators, with conflicts resolved in the same manner. The following data were extracted from all studies: study design, year of study, interventions investigated, population investigated, size of study population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, outcomes reported, whether outcomes were primary or secondary, time-points at which outcomes were measured, which of the criteria for complete reporting the study met, and the ORBIT grade5 for each investigated outcome. ORBIT grades range from A-I and are used to denote the completeness of reporting for a particular outcome.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All study designs except case studies and expert opinion were considered for inclusion in the review. Studies where only the abstract was available (e.g. conference proceedings) were not included in the assessment of completeness of data reporting, as this could only be analysed from the full study report. The search was limited to papers published after 2010 in order to ensure that the outcomes identified by the review remained contemporaneous. Only studies including more than 10 infants were eligible for inclusion.

Additionally, Hirschsprung’s Disease studies were eligible for inclusion if they:

Compared two or more interventions for infants with biopsy confirmed Hirschsprung’s Disease and

Reported outcomes following the primary definitive procedure.

Additionally, Hirschsprung’s Disease studies were excluded if:

They only reported outcomes from one intervention without a comparator.

They only reported outcomes for infants undergoing a re-do procedure or

They only reported outcomes from the non-definitive procedure e.g. stoma formation in infants planned for a staged procedure.

Additionally, gastroschisis studies were eligible for inclusion if they compared two or more methods of visceral reduction and defect closure in infants with gastroschisis, and were excluded if they only reported outcomes from one intervention without a comparator.

Both searches were undertaken in August 2015.

Outcome description

The primary aim of this study was to generate a list of all outcomes investigated by eligible studies. The median number of outcomes reported per study was calculated as a secondary outcome measure. Similar outcomes were merged to one common term prior to analysis.

Outcome terms were then assigned to one of the five core areas from the OMERACT filter 2.0. The OMERACT filter 2.0 represents five core areas that should be covered by outcomes in order to ensure a full breadth of reporting10. These areas are (1) adverse events, (2) life impact, (3) resource use, (4) pathophysiological manifestations, and (5) death.

Completeness of reporting

A secondary aim of this review was to determine the completeness of outcome reporting in Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis studies. Harman et al. proposed five core questions that could be used to assess how transparently researchers had identified and reported their choice of outcomes11, whilst the ORBIT criteria are used to determine whether it is likely that data is missing from the studies report5. The percentage of studies meeting all five of Harman et al.’s core criteria for complete, transparent outcome reporting, and the percentage of studies reporting full data, as described by the ORBIT criteria were calculated for all outcomes investigated. Harman et al.’s five core criteria are:

Is the primary outcome clearly stated?

Is the primary outcome clearly defined so that another researcher would be able to reproduce its measurement?

Are the secondary outcomes clearly stated?

Are the secondary outcomes clearly defined?

Do the authors explain the use of the outcomes which they have selected?

Data Synthesis

The number of outcomes reported in each eligible study and the number of times each outcome was reported were counted, and the medians and interquartile ranges calculated. The number and percentage of studies answering yes to all five core questions proposed by Harman et al., and the number and percentage with full reporting according to ORBIT criteria for all investigated outcomes were also calculated.

Results

Hirschsprung’s Disease included studies

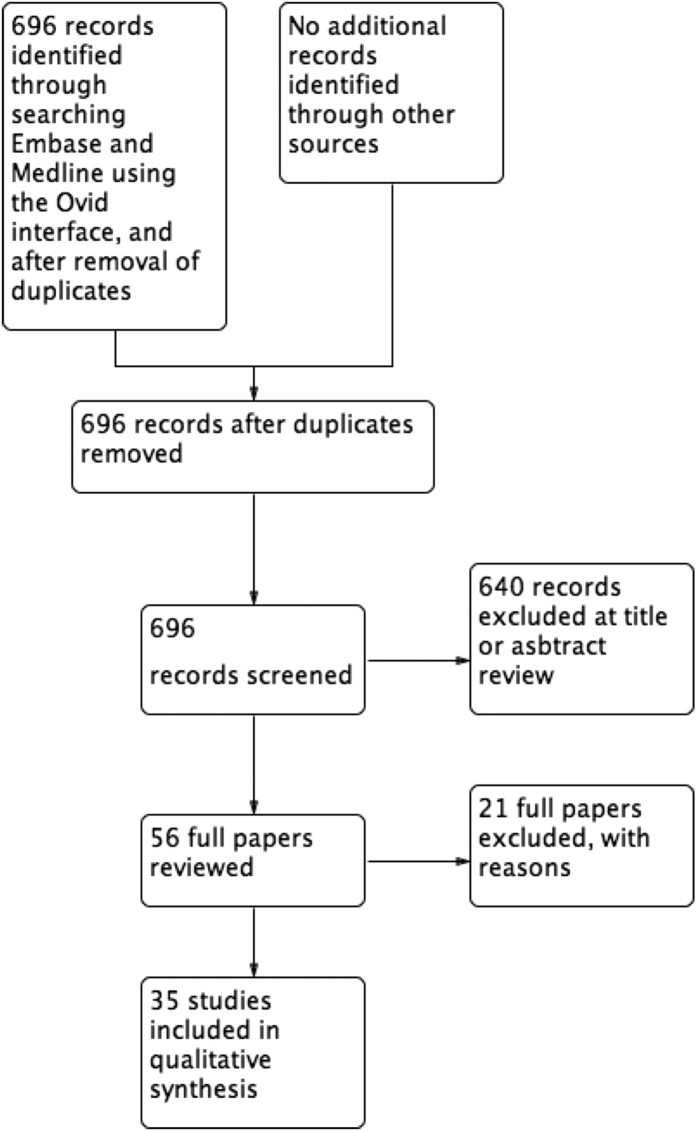

The search retrieved 696 unique titles related to Hirschsprung’s Disease, 640 of which were excluded following title and abstract review. Following full paper review, a further 21 papers were excluded with reasons (Supplementary File 3), leaving 35 studies as eligible for inclusion in the review (Fig. 1). Eighteen manuscripts (51%) were retrospective case series, nine (26%) were prospective cohort studies, three (9%) were case control studies, three (9%) were systematic reviews, one (3%) was a registry based study, and one (3%) was a randomised controlled trial. The median number of study participants was 62 (IQR44-156).

Figure 1. Hirschsprung’s Disease PRISMA flow chart.

Hirschsprung’s Disease reported outcomes

In the 35 included studies, 95 outcomes were investigated a total of 337 times. Thirty-five outcomes were considered to be too similar to at least one other outcome to be meaningfully differentiated, and these outcomes were therefore mapped to one common term (e.g. continence/incontinence, or frequency of stool/bowel movement frequency). Following this exercise, 74 unique outcomes were identified as having been reported (Table 1).

Table 1. Hirschsprung’s Disease outcomes and number of times reported, grouped according to OMERACT filter 2.0.

| Outcome | Number of times reported | Outcome | Number of times reported | Outcome | Number of times reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development-Social | 1 | Medication-laxative | 2 | Narrowing of anastomosis or cuff | 22 |

| Sleep disturbance | 1 | Dilations | 1 | Impotence | 1 |

| Depression | 1 | Continence-urinary | 1 | Abdominal distension | 3 |

| Psychological stress | 1 | Manometry | 1 | Sphincter achalasia | 1 |

| Cosmetic results | 2 | Bowel Movement-first post-op | 3 | Feeding intolerance | 1 |

| Parenteral nutrition use | 1 | Early pelvic inflammation | 1 | Post-operative infection | 9 |

| Time until first feed (post-operatively) | 7 | Bladder Dysfunction | 1 | Fever | 1 |

| Diet tolerated | 1 | Aganglionic bowel remaining | 1 | Abscesses | 5 |

| Assessment of bowel function | 1 | Death | 7 | Anastomotic Leak | 13 |

| Bowel Function Score (BFS) questionnaire | 2 | Intra-operative complication | 4 | Pneumonia | 2 |

| Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) questionnaire | 2 | Intra-operative visceral injury | 2 | Dehiscence | 7 |

| Krickenbeck score | 2 | Colonic torsion | 2 | Enterocolitis | 23 |

| Sensation of need to defecate | 2 | Ischaemia | 1 | Granuloma | 1 |

| Voluntary bowel movements | 2 | Conversion | 6 | Colostomy morbidity | 1 |

| Frequency of bowel movements | 13 | Intra-operative blood loss | 13 | Herniation | 6 |

| Time to normal bowel habits | 1 | Reoperations | 11 | Colostomy retractions | 1 |

| Long-term bowel dysfunction | 1 | Excoriation | 10 | Late or adhesional obstruction | 7 |

| Faecal Impaction | 1 | Anal lacerations | 1 | Operation length | 17 |

| Constipation | 20 | Fistula | 1 | Time of antibiotic administration | 1 |

| Diarrhoea | 3 | Necrosis of and retraction of colon | 1 | Analgesic use post-operatively | 2 |

| Consistency of stool | 3 | Adhesions | 1 | ICU admission | 1 |

| Urgency period | 3 | Post-operative ‘complications’ | 3 | Hospital stay (length) | 18 |

| Requiring nappy | 1 | Early or persistent obstruction | 8 | Readmission | 2 |

| Faecal incontinence | 32 | Prolapse | 2 | Cost | 2 |

| Encopresis | 1 | Rectal muscularis infection | 1 |

Bold is life impact, Italic is pathophysiological manifestations, Bold italic is mortality, underlined bold is adverse events, and underlined is resource utilisation.

Outcomes were mapped to the OMERACT filter 2.0. Overall, 33 ‘adverse event’ outcomes, 28 ‘life impact’ outcomes, seven ‘resource use’ outcomes, five ‘pathophysiological manifestation’ outcomes, and one ‘death’ outcome were reported. Adverse event outcomes accounted for 171 of the 338 outcomes that studies investigated (51%), whilst life impact outcomes accounted for 109 (32%).

Overall, faecal incontinence was the most commonly reported outcome and, appearing in 32 studies (91%), the only one to be investigated in more than 75% of studies. Outcomes investigated in more than 50% of studies were enterocolitis (23 studies, 66%), constipation (20 studies, 57%) and length of stay (18 studies, 51%). Thirty-three (45%) of the 74 unique outcomes were only investigated in one study. The median number of outcomes investigated per study was 11 (IQR6-13). Due to the retrospective nature of many of the included studies, and the lack of clearly defined end-points within them, it was not possible to make any meaningful assessment of the ages at which key outcomes were measured.

Hirschsprung’s Disease Completeness of reporting

Of the 35 included studies, seven (20%) were available only as abstracts and were therefore excluded from assessment of overall quality and completeness of reporting. Of the remaining 28 studies, only 7 (25%) met all five of the core criteria that Harman et al. describe for achieving complete, high quality reporting of a study’s results. When assessed against the ORBIT criteria, of the 28 full papers, only seven (25%) fully reported each of the outcomes they set out to investigate (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of outcomes reported and completeness of outcome reporting in Hirschsprung’s Disease studies.

| Study | Design | Number of infants | Number of outcomes reported | Meets all core criteria for complete high quality reporting | Complete data reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ademuyiwa, A. O. et al. 201213 | Retrospective case series | 29 | 7 | No | No |

| Aworanti, O. M. et al.14 | Retrospective case series | 51 | 4 | Yes | Yes |

| Chen, Y. et al.15 | Systematic Review | 131 | 6 | No | Yes |

| Dahal, G. R. et al.16 | Retrospective case series | 11 | 15 | Yes | No |

| Duncan, N. D. et al.17 | Retrospective case series | 45 | 8 | No | No |

| Dutta, H. K. et al.18 | Prospective cohort | 62 | 13 | No | No |

| El-Sawaf, M. et al.19 | RCT | 22 | 2 | Yes | Yes |

| Fernandez Ibieta, M. et al.20 | Case-Control | 38 | 4 | Yes | Yes |

| Fernandez Ibieta, M. et al.21 | Retrospective case series | 220 | 11 | No | No |

| Gao, M. T. et al.22 | Prospective cohort | 70 | 2 | No | No |

| Giuliani, S. et al.23 | Retrospective case series | 29 | 13 | No | No |

| Gosemann et al.24 | Systematic Review | 159 | 4 | No | Yes |

| Gunnarsdottir, A. et al.25 | Prospective cohort | 281 | 15 | No | Yes |

| Jarvi, K. et al.26 | Case control | 101 | 14 | Yes | No |

| Kim, A. C. et al.27 | Retrospective case series | 110 | 14 | No | No |

| Li, L. Z. et al.28 | Retrospective case series | 14 | 4 | No | No |

| Mabula, J. B. et al.29 | Prospective cohort | 181 | 13 | No | No |

| Miyano, G. et al.30 | Retrospective case series | 54 | 10 | No | No |

| Nah, S. A. et al.31 | Retrospective case series | 53 | 11 | No | No |

| Nasr, A. et al.32 | Case control | 52 | 13 | Yes | No |

| Romero, P. et al.33 | Retrospective case series | 11 | 14 | No | No |

| Stensrud, K. J. et al.34 | Prospective cohort | 1555 | 14 | No | No |

| Stensrud, K. J. et al.35 | Prospective cohort | 58 | 11 | No | No |

| Sulkowski, J. P. et al.36 | registry | 218 | 12 | No | No |

| Tang, S. et al.37 | Retrospective case series | 72 | 10 | No | No |

| Tang, S. T. et al.38 | Retrospective case series | 20 | 11 | No | No |

| Tang, W. et al.39 | Retrospective case series | 43 | 5 | No | No |

| Thomson, D. et al.2 | Systematic Review | 50 | 15 | Yes | Yes |

| Travassos, D. et al.40 | Retrospective case series | 90 | 10 | No | No |

| Van de Ven, T. J. et al.41 | Retrospective case series | 153 | 11 | No | No |

| Visser, R. et al.42 | Retrospective case series | 54 | 14 | No | No |

| Vorobyov, G. I. et al.43 | Retrospective case series | 84 | 7 | No | No |

| Wang, L. et al.44 | Prospective cohort | 792 | 6 | No | No |

| Yang, L. et al.45 | Prospective cohort | 1412 | 10 | No | No |

| Yang, L. et al.46 | Prospective cohort | 405 | 4 | No | No |

Gastroschisis included Studies

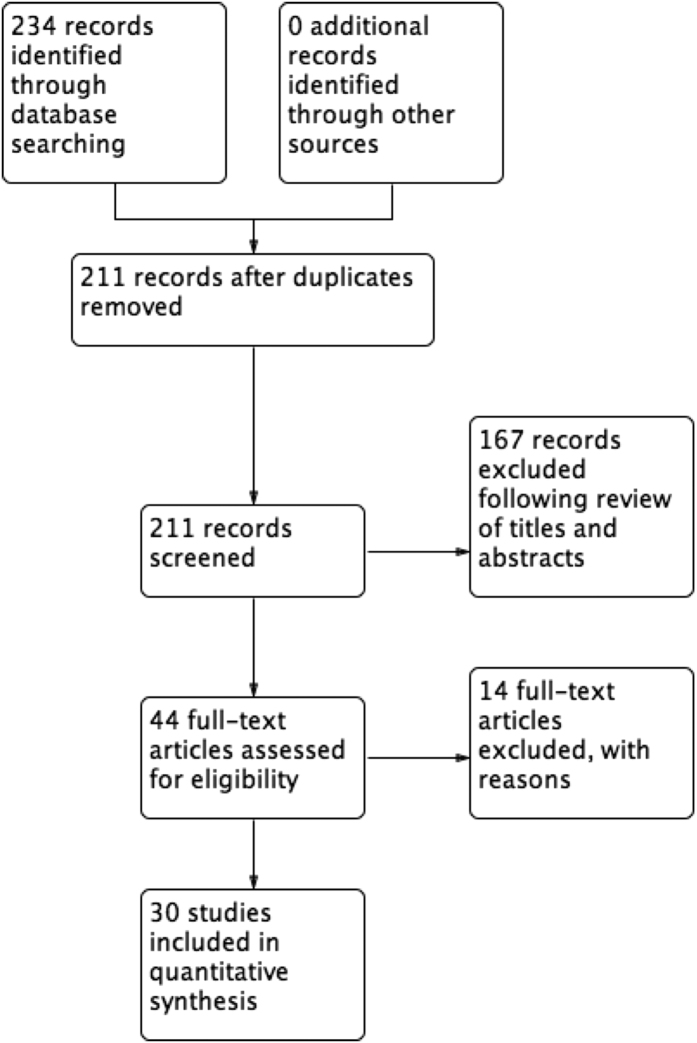

The search strategy returned 234 titles related to gastroschisis, reduced to 211 after exclusion of duplicates. Following review of titles and abstracts, 167 records were excluded. A further fourteen records were then excluded with reasons following full paper analysis (Supplementary File 4), resulting in 30 studies that were deemed eligible for inclusion in the review (Fig. 2). Twenty-two papers (73%) were retrospective case series, four were prospective cohort studies (13%), two were systematic reviews (7%), one was a case-control study (3%), and one was a registry study (3%). There were no eligible randomised controlled trials. The median number of study participants was 122 (IQR 53-285).

Figure 2. Gastroschisis PRISMA flow chart.

Gastroschisis outcomes

Within the included studies, 102 outcomes were investigated a total of 247 times. Within these 102 outcomes there were 63 that were felt to be too similar to at least one other outcome to be meaningfully differentiated, and these were therefore mapped to one common term. Following this mapping process, there remained 62 unique outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3. Gastroschisis outcomes and number of times reported, grouped according to OMERACT filter 2.0.

| Outcome | Number of times reported | Outcome | Number of times reported | Outcome | Number of times reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time ontotal parenteral nutrition | 9 | Bacteraemia | 2 | Infection, unspecified or other | 7 |

| Time on parenteral nutrition | 12 | pH, time acidotic | 1 | Infection, central line related | 6 |

| Parenteral nutrition ever required | 1 | Kidney dysfunction | 1 | Wound infection or breakdown | 12 |

| Parenteral nutrition required post-discharge | 1 | Urine output | 3 | Infection with systemic sequelae | 8 |

| Feeding, initiation of feed in NICU | 1 | Blood pressure, mean arterial | 1 | Infection free survival | 1 |

| Feeding, full feeds at discharge from NICU | 1 | Need for mesh at closure | 1 | Infection, urinary or respiratory | 3 |

| Time to first oral feed | 13 | weight <10th centile | 1 | Number of transfusions | 1 |

| Time to full oral feeds | 13 | weight gain | 1 | Silo Complication | 2 |

| Short Bowel Syndrome | 4 | Hypothyroidism | 1 | Ischaemic bowel | 2 |

| bowel lengthening procedure required | 1 | Length of stay | 24 | Anastomotic stricture | 2 |

| liver transplantation | 1 | NICU length of stay | 4 | Intestinal perforation | 3 |

| Neurodevelopmental delay | 1 | Discharge, NICU to home | 1 | Abdominal compartment syndrome | 7 |

| Total time on mechanical ventilation | 13 | General anaesthesia, number of days, indication | 1 | NEC | 16 |

| Post closure time on mechanical ventilation | 3 | Central-line usage ratio (days with central line/hospital days) | 1 | Stoma complication | 2 |

| Ventilation, peak inspiratory pressure | 1 | Duration of antibiotics | 3 | Adhesional small bowel obstruction | 3 |

| Ventilation, peak concentration inspired oxygen | 1 | Hospital charge | 2 | Intestinal Failure Associated Liver Disease | 6 |

| Post-operative ventilation required | 1 | Days to abdominal wall closure | 1 | Unplanned reoperation | 9 |

| Respiratory compromise | 1 | rehospitalisation | 1 | Reoperation, need for enlargement of gastroschisis defect | 1 |

| Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome | 1 | Mortality | 19 | Reoperation, need for silo replacement | 1 |

| Cholestasis | 2 | GI complication | 1 | Umbilical hernia | 3 |

| Volume of IV fluid required | 1 | Non-GI complication | 1 |

Bold is life impact, Italic is pathophysiological manifestations, Bold italic is mortality, underlined bold is adverse events, and underlined is resource utilisation.

Outcomes were mapped to the OMERACT filter 2.0. Overall, 22 ‘adverse event’ outcomes (35%), 18 ‘pathophysiological manifestation’ outcomes (29%), 12 ‘life impact’ outcomes (20%), nine ‘resource use’ outcomes (15%), and one ‘death’ outcome (1%) were reported. ‘Adverse event’ outcomes were reported 97 times (39% of all reported outcomes), whilst ‘life impact’ outcomes were reported 58 times (23% of all reported outcomes).

Eight of the 62 identified outcomes related to feeding (13%), and five related to mechanical ventilation (8%). These two areas therefore appear to be of interest to researchers. However, the greatest number of studies in which any individual outcome from either of these areas was investigated was 13 (43%), suggesting there is little agreement on what the most important outcome in each area is. Overall, the most commonly investigated outcome was total length of stay, appearing in 24 studies (80%). Mortality (19 studies, 63%), and development of necrotising enterocolitis (16 studies, 53%) were the only other outcomes to be reported in more than 50% of studies. The median number of times an outcome was reported was once (IQR1-2). Thirty-one outcomes (50%) were only reported in one study. The median number of outcomes reported per study was 9 (IQR5-11).

Gastroschisis completeness of reporting

Of the 30 included studies, three were only available as abstracts, and therefore excluded from analysis of completeness and quality of reporting. Of the remaining 27 studies, none met all five of the core criteria defined by Harman et al. for complete, high quality outcome reporting. When assessed against the ORBIT criteria, 12 studies (44%) fully reported each of the outcomes they set out to investigate (Table 4).

Table 4. Number of outcomes reported and completeness of outcome reporting in gastroschisis studies.

| Study | Design | Number of infants | Number of outcomes reported | Meets all core criteria for complete high quality reporting11 | Complete data reporting5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alali et al.47 | Retrospective Case Series | 86 | 4 | No | Yes |

| Allin et al.1 | Systematic Review | 804 | 14 | No | Yes |

| Banyard et al.48 | Retrospective Case Series | 235 | 10 | No | Yes |

| Barrett et al.49 | Retrospective Case Series | 70 | 4 | No | No |

| Bradnock et al.50 | Prospective Cohort Study | 301 | 15 | No | No |

| Charlesworth et al.51 | Retrospective Case Series | 156 | 9 | No | Yes |

| Chesley et al.52 | Retrospective Case Series | 202 | 3 | No | No |

| Dariel et al.53 | Retrospective Case Series | 64 | 15 | No | Yes |

| Erdogan et al.54 | Retrospective Case Series | 29 | 12 | No | No |

| Kandasamy et al.55 | Retrospective Case Series | 50 | 13 | No | No |

| Kassa et al.56 | Retrospective Case Series | 79 | 3 | No | No |

| Kunz et al.3 | Systematic Review | 1879 | 8 | No | Yes |

| Lobo et al.57 | Retrospective Case Series | 37 | 10 | No | No |

| Lusk et al.58 | Retrospective Case Series | 168 | 8 | No | No |

| McNamara et al.59 | Retrospective Case Series | 30 | 3 | Abstract Only | Abstract Only |

| Muniz et al.60 | Retrospective Case Series | 61 | 1 | Abstract Only | Abstract Only |

| Murthy et al.61 | Retrospective Case Series | 442 | 11 | No | Yes |

| Niramis et al.62 | Retrospective Case Series | 919 | 4 | No | Yes |

| Orion et al.63 | Retrospective Case Series | 80 | 10 | No | No |

| Owen et al.64 | Prospective Cohort Study | 393 | 9 | No | Yes |

| Payne et al.65 | Case Control Study | 116 | 2 | Abstract Only | Abstract Only |

| Safavi et al.66 | Registry | 402 | 7 | No | Yes |

| Santos Schmidt et al.67 | Retrospective Case Series | 45 | 7 | No | No |

| Schlueter et al.68 | Retrospective Case Series | 129 | 12 | No | No |

| Schmidt et al.69 | Prospective Cohort Study | 45 | 8 | No | No |

| Sirichaipornsak et al.70 | Retrospective Case Series | 15 | 9 | No | No |

| Stanger et al. 201071 | Retrospective Case Series | 679 | 6 | No | Yes |

| Tsai et al.72 | Retrospective Case Series | 44 | 8 | No | No |

| Van Manen et al.73 | Prospective Cohort Study | 167 | 12 | No | Yes |

| Weil et al.74 | Retrospective Case Series | 190 | 10 | No | No |

Discussion

This review shows substantial heterogeneity of outcome reporting in Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis studies. For each condition, over 60 unique outcomes were investigated, only 5% of which were investigated in more than half of the included studies, and over 40% of which were only investigated in one study.

Within Hirschsprung’s Disease research, 32% of investigated outcomes were in the ‘life impact’ core area of the OMERACT filter 2.0, suggesting that there is potential for current research to be investigating outcomes of relevance to patients. The lack of meaningful information on when outcomes are measured however, meant that it was not possible to determine whether these outcomes were investigated at time points where their results would be considered valid (e.g. whether faecal continence was measured in infants who were old enough to be expected to be continent). With 64% of gastroschisis outcomes fitting into either the ‘pathophysiological manifestations’ or ‘adverse events’ core areas, it would suggest that gastroschisis research tends to have a shorter-term focus. With no gastroschisis studies, and only 25% of Hirschsprung’s Disease studies meeting all of the criteria for high quality, complete outcome reporting, and only 25% of Hirschsprung’s Disease and 44% of gastroschisis studies fully reporting all outcome data, there also appears to be a high risk of reporting bias within both research fields.

The search strategy and inclusion criteria for this study were designed to be sensitive whilst maintaining contemporaneity of the identified outcomes. This should provide the most robust basis for development of a core outcome set. Excluding studies conducted prior to 2010 does however introduce the potential for these reviews to miss important outcomes that were fully investigated in high quality studies prior to this point. One example of this is the only randomised controlled trial carried out to date which compares operative primary fascial closure with silo placement for treatment of gastroschisis12. Such exclusions have the potential to alter the data on completeness of reporting. However, we were unable to identify any plausible reasons why the study designs used, or quality of reporting should be significantly different pre and post 2010. We therefore do not believe that these exclusions will have significantly altered the conclusions of this review. By including in the current analysis outcomes investigated by systematic reviews, outcomes reported by significant primary studies prior to 2010 (including that of Pastor et al.) should also have been captured, and will therefore be included in the list of outcomes used for the development of the core outcome sets.

In order to assess the quality and completeness of outcome reporting, we used tools that were initially designed for assessing randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews. However, it is not unreasonable to expect that any study making active comparison of two interventions meets all five of Harman et al.’s core criteria for high quality, transparent reporting, and that they fully report data for all stated a priori outcomes.

It has previously been suggested that variability in outcome definition and reporting is limiting the development of a high quality evidence in Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis1,2,4. Our review reinforces that message, and adds to it by suggesting that there is also a high risk of reporting bias in research into both conditions, thereby further reducing the reliability of conclusions drawn from the current literature. This high risk of reporting bias echoes what was shown in a large selection of randomised controlled trials included in Cochrane systematic reviews5.

The focus of the included studies on pathophysiological manifestations and adverse events, and lack of clarity of time-points for measurement of life impact outcomes raises the possibility that patients and their parents were not involved in determining which outcomes should be investigated by researchers and clinicians. This apparent lack of knowledge as to which outcomes are important to patients and parents in determining the success of gastroschisis and Hirschsprung’s Disease treatment may account in part for the heterogeneity of outcome reporting that our reviews have demonstrated. The difficulties this heterogeneity creates for supporting clinical practice are compounded by the high risk of reporting bias that this review has also demonstrated. Both of these factors suggest that at present, caution should be exercised when using the existing literature to argue in favour of a particular treatment for either condition. There are two concrete steps that can be taken to remedy this situation, firstly, development of core outcome sets for use in gastroschisis and Hirschsprung’s Disease, and secondly, enhanced national and international collaborative research studies and trials. These measures would reduce reporting bias, ease meta-analysis, increase statistical power to answer clinically relevant questions, and improve the patient relevance of research7,8,9.

These systematic reviews provide the evidence that development and implementation of core outcome sets are required for Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis. The outcomes identified by these reviews could be used as the starting point for a robust Delphi processes involving patients, parents and multi-disciplinary clinical groups to develop such core outcome sets. These will be the first core outcome sets to be developed for any paediatric surgical condition, and we do not wish them to be developed simply as an academic exercise. Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis were specifically chosen as the first conditions in which to develop paediatric surgical core outcome sets in order to limit the possibility of this occurring. We believe they limit this risk for two reasons. Firstly, both conditions are actively studied at present, and therefore, have a community of researchers who are anticipating the use of the developed core outcome sets. Secondly, there have been contemporaneous, UK-wide cohorts of infants established for both conditions, in whom long-term follow-up studies could be conducted utilising the developed core outcome sets. We have elected to present the results of both systematic reviews as one manuscript, as there are several common themes which lend themselves to being demonstrated best through reporting in a single article. Doing this illustrates to the paediatric surgical community the need for development and implementation of core outcome sets in both of these conditions, and potentially, in others as well.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Allin, B. S. R. et al. Variability of outcome reporting in Hirschsprung’s Disease and gastroschisis: a systematic review. Sci. Rep. 6, 38969; doi: 10.1038/srep38969 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Marian Knight is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Professorship. This paper presents independent research partially funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. Benjamin Allin is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Research Fellowship. This paper presents independent research partially funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions B.A. conceived the idea for the study. B.A. and M.K. were responsible for design, analysis and interpretation of the work. B.A., A.I. and N.P. were responsible for acquisition and analysis of data for the work. B.A. was responsible for drafting the manuscript, all other authors contributed to revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors give final approval of the version to be published and give an agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. B.A. and M.K. act as guarantors for the work. The lead author affirms that he had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- Allin B. S., Tse W. H., Marven S., Johnson P. R. & Knight M. Challenges of improving the evidence base in smaller surgical specialties, as highlighted by a systematic review of gastroschisis management. PloS one 10, e0116908, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116908 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson D. et al. Laparoscopic assistance for primary transanal pull-through in Hirschsprung’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open 5, e006063, doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006063 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S. N., Tieder J. S., Whitlock K., Jackson J. C. & Avansino J. R. Primary fascial closure versus staged closure with silo in patients with gastroschisis: a meta-analysis. Journal of pediatric surgery 48, 845–857, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.01.020 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. Transanal endorectal pull-through versus transabdominal approach for Hirschsprung’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of pediatric surgery 48, 642–651, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.12.036 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham J. J. et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 340, c365, doi: 10.1136/bmj.c365 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allin B. et al. What Evidence Underlies Clinical Practice in Paediatric Surgery? A Systematic Review Assessing Choice of Study Design. PloS one 11, e0150864, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150864 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson P., Altman D., Blazeby J., Clarke M. & Gargon E. Driving up the quality and relevance of research through the use of agreed core outcomes. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 17, 1–2, doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011131 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson P., Altman D., Blazeby J., Clarke M. & Gargon E. The COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) Initiative. Trials 12, A70, doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-S1-A70 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Molano W. et al. How well are the ASAS/OMERACT Core Outcome Sets for Ankylosing Spondylitis implemented in randomized clinical trials? A systematic literature review. Clin Rheumatol 33, 1313–1322, doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2728-6 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boers M. et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. Journal of clinical epidemiology 67, 745–753, doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.013 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman N. et al. MOMENT-Management of Otitis Media with Effusion in Cleft Palate: protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. Trials 14, 70 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor A. C. et al. Routine use of a SILASTIC spring-loaded silo for infants with gastroschisis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Journal of pediatric surgery 43, 1807–1812 (2008). http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/691/CN-00666691/frame. html http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0022346808003679/1-s2.0-S0022346808003679-main.pdf?_tid=93d087f6-42b0-11e2-bcb8-00000aacb360&acdnat=1355133873_7d4b16422f86336a02e6fd2f00d56831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ademuyiwa A. O., Bode C. O., Lawal O. A. & Seyi-Olajide J. Swenson’s pull-through in older children and adults: Peculiar peri-operative challenges of surgery. International Journal of Surgery 9, 652–654 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aworanti O. M., McDowell D. T., Martin I. M., Hung J. & Quinn F. Comparative review of functional outcomes post surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease utilizing the paediatric incontinence and constipation scoring system. Pediatric Surgery International 28, 1071–1078, doi: 10.1007/s00383-012-3170-y. (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. Transanal endorectal pull-through versus transabdominal approach for Hirschsprung’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 48, 642–651, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.12.036. (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahal G. R., Wang J. X. & Guo L. H. Long-term outcome of children after single-stage transanal endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease. World Journal of Pediatrics 7, 65–69, doi: 10.1007/s12519-011-0247-y. (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan N. D., Plummer J., Dundas S. E., Martin A. & McDonald A. H. Adult Hirschsprung’s disease in Jamaica: Operative treatment and outcome. Colorectal Disease 13, 454–458, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02174.x. (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta H. K. Clinical experience with a new modified transanal endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease. Pediatric Surgery International 26, 747–751, doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2629-y (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sawaf M., Siddiqui S., Mahmoud M., Drongowski R. & Teitelbaum D. H. Probiotic prophylaxis after pullthrough for Hirschsprung disease to reduce incidence of enterocolitis: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 48, 111–117, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.10.028 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Ibieta M. et al. Quality of life and long term results in Hirschsprung’s disease. Cirugia Pediatrica 27, 117–124 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Ibieta M. et al. Functional results of Hirschsprung’s disease patients after Duhamel and De la Torre procedures. [Spanish]. Cirugia pediatrica: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Cirugia Pediatrica 26, 183–188 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M. T. et al. Evaluation of long-term bowel function in patients with Hirschsprung’s disease after different radical operations. [Chinese]. World Chinese Journal of Digestology 18, 2491–2495 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani S. et al. Outcome comparison among laparoscopic duhamel, laparotomic duhamel, and transanal endorectal pull-through: A single-center, 18-year experience. Journal of Laparoendoscopic and Advanced Surgical Techniques 21, 859–863, doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0107. (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosemann J. H., Friedmacher F., Ure B. & Lacher M. Open versus transanal pull-through for hirschsprung disease: A systematic review of long-term outcome. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 23, 94–102, doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343085. (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsdottir A., Larsson L. T. & Arnbjornsson E. Transanal endorectal vs. duhamel pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 20, 242–246, doi: 0.1055/s-0030-1252006. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvi K., Laitakari E. M., Koivusalo A., Rintala R. J. & Pakarinen M. P. Bowel function and gastrointestinal quality of life among adults operated for hirschsprung disease during childhood: A population-based study. Annals of Surgery 252, 977–981, doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182018542. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A. C. et al. Endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease-a multicenter, long-term comparison of results: transanal vs transabdominal approach. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 45, 1213–1220, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.087. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. Z. et al. Analysis of prognosis of surgical treatment to patients with Hirschsprung disease. [Chinese]. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Medical Science) 35, 86–90 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Mabula J. B. et al. Hirschsprung’s disease in children: a five year experience at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania. BMC research notes 7, 410, doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-410. (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyano G., Ochi T., Lane G. J., Okazaki T. & Yamataka A. Factors affected by surgical technique when treating total colonic aganglionosis: Laparoscopy-assisted versus open surgery. Pediatric Surgery International 29, 349–352, doi: 10.1007/s00383-012-3247-7. (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nah S. A. et al. Duhamel pull-through for Hirschsprung disease: A comparison of open and laparoscopic techniques. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 47, 308–312, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.11.025. (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr A., Haricharan R. N., Gamarnik J. & Langer J. C. Transanal pullthrough for Hirschsprung disease: Matched case-control comparison of Soave and Swenson techniques. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49, 774–776, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.02.073. (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero P. et al. Outcome of transanal endorectal vs. transabdominal pull-through in patients with Hirschsprung’s disease. Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery 396, 1027–1033, doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0804-9 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensrud K. J., Emblem R. & Bjornland K. Functional outcome after operation for Hirschsprung disease-transanal vs transabdominal approach. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 45, 1640–1644, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.065. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensrud K. J., Emblem R. & Bjornland K. Late diagnosis of Hirschsprung disease-Patient characteristics and results. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 47, 1874–1879, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.04.022. (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski J. P. et al. Single-stage versus multi-stage pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease: Practice trends and outcomes in infants. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49, 1619–1625, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.06.002. (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S. T. et al. Single-incision laparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung’s Disease: A comparison of short-term surgical results. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 48, 1919–1923, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.11.044. (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S. T., Yang Y. & Wang G. B. Laparoscopic-assisted endorectal soave pull-through procedure for hirschsprung’s disease: A 10-year experience from a single institution in China. Journal of Laparoendoscopic and Advanced Surgical Techniques 21(4), A3, doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0081. (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. et al. Fast track surgery combined with laparoscopy in the treatment of infant Hirschsprung disease. [Chinese]. Zhonghua wei chang wai ke za zhi = Chinese journal of gastrointestinal surgery 17, 805–808 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travassos D., Van Herwaarden-Lindeboom M. & Van Der Zee D. C. Hirschsprung’s disease in children with down syndrome: A comparative study. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 21, 220–223, doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271735. (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Ven T. J. et al. Transanal endorectal pull-through for classic segment Hirschsprung’s disease: with or without laparoscopic mobilization of the rectosigmoid? Journal of Pediatric Surgery 48, 1914–1918, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.04.025. (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser R., van de Ven T. J., van Rooij I. A., Wijnen R. M. & de Blaauw I. Is the Rehbein procedure obsolete in the treatment of Hirschsprung’s disease? Pediatric Surgery International 26, 1117–1120, doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2696-0. (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorobyov G. I., Achkasov S. I. & Biryukov O. M. Clinical features’ diagnostics and treatment of Hirschsprung’s disease in adults. Colorectal Disease 12, 1242–1248, doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02031.x. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. et al. Application of partial internal sphincter myomectomy in patients with Hirschsprung disease undergoing transanal one-stage pull-through operation. [Chinese]. Zhonghua wei chang wai ke za zhi = Chinese journal of gastrointestinal surgery 16, 651–653 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. & Tang S. T. A prosective study of laparoscopic transanal endorectal pull-through for subtotal colectomy in hirschsprung’s disease: Anastomosis using long cuff or short cuff? Journal of Laparoendoscopic and Advanced Surgical Techniques 23(12), A-20, doi: 0.1089/lap.2013.0299. (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Wang G. B., Cao G. Q., Tang S. T. & Huang X. A comparison of the effectiveness of the laparoscopic-assisted soave and duhamel procedures for children with long aganglionic segment. Journal of Laparoendoscopic and Advanced Surgical Techniques 23(12), A-21, doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0184 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alali J. S., Tander B., Malleis J. & Klein M. D. Factors affecting the outcome in patients with gastroschisis: How important is immediate repair? European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 21, 99–102, doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267977 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard D. et al. Method to our madness: an 18-year retrospective analysis on gastroschisis closure. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 45, 579–584, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.08.004. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett M. J. et al. The national incidence and outcomes of gastroschisis repairs. Irish Medical Journal 107, 83–85 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradnock T. J. & Walker G. M. Evolution in the management of Hirschsprung’s disease in the UK and Ireland: a national survey of practice revisited. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 93, 34–38, doi: 10.1308/003588410x12771863936846 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth P. et al. Preformed silos versus traditional abdominal wall closure in gastroschisis: 163 infants at a single institution. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 24, 88–93, doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1357755. (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesley P. M., Ledbetter D. J., Meehan J. J., Oron A. P. & Javid P. J. Contemporary trends in the use of primary repair for gastroschisis in surgical infants. American Journal of Surgery 209, 901–906, doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.01.012. (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dariel A., Poocharoen W., De Silva N., Pleasants H. & Gerstle J. T. Secondary plastic closure of gastroschisis is associated with a lower incidence of mechanical ventilation. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 25, 34–40, doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1395487 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan D. et al. 11-year experience with gastroschisis: Factors affecting mortality and morbidity. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics 22, 339–343 (2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy Y., Whitehall J., Gill A. & Stalewski H. Surgical management of gastroschisis in North Queensland from 1988 to 2007. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 46, 40–44, doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2009.01615.x. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassa A. M. & Lilja H. E. Predictors of postnatal outcome in neonates with gastroschisis. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 46, 2108–2114, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.07.012. (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo J. D. et al. No free ride? The hidden costs of delayed operative management using a spring-loaded silo for gastroschisis. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 45, 1426–1432, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.047. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk L. A. et al. Multi-institutional practice patterns and outcomes in uncomplicated gastroschisis: A report from the University of California Fetal Consortium (UCfC). Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49, 1782–1786, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.09.018 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara W. F., Hartin C. W., Escobar M. A. & Lee Y. Outcome differences between gastroschisis repair methods. Journal of Surgical Research 158(2), 366, doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.05.054 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniz V., Zandonade E. & Lima Netto A. Outcomes in outborn babys with gastroschisis in a pediatric brazilian hospital. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 1, 148, doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000449381.95708.a3 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy K. et al. The association of type of surgical closure on length of stay among infants with gastroschisis born >34 weeks gestation. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49, 1220–1225, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.12.020 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niramis R. et al. Clinical outcome of patients with gastroschisis: what are the differences from the past? Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet 94 Suppl 3, S49–56 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orion K. C. et al. Outcomes of plastic closure in gastroschisis. Surgery 150, 177–185, doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.05.001 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen A. et al. Gastroschisis: A national cohort study to describe contemporary surgical strategies and outcomes. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 45, 1808–1816, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.01.036. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne N. R. et al. A cross-sectional, case-control follow-up of infants with gastroschisis. Journal of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine 3, 207–215, doi: 10.3233/NPM-2010-0117 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi A., Skarsgard E. & Butterworth S. Bowel-defect disproportion in gastroschisis: Does the need to extend the fascial defect predict outcome? Pediatric Surgery International 28, 495–500, doi: 10.1007/s00383-012-3055-0 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos Schmidt A. F. et al. Monitoring intravesical pressure during gastroschisis closure. Does it help to decide between delayed primary or staged closure? Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 25, 1438–1441, doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.640366 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter R. K. et al. Identifying strategies to decrease infectious complications of gastroschisis repair. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50, 98–101, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.10.001 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A. F. et al. Does staged closure have a worse prognosis in gastroschisis? Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 66, 563–566 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirichaipornsak S., Jirapradittha J., Kiatchoosakun P. & Suphakunpinyo C. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with gastroschisis at university hospital in northeast Thailand. Asian Biomedicine 5, 861–866 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Stanger J., Mohajerani N. & Skarsgard E. D. Practice variation in gastroschisis: Factors influencing closure technique. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49, 720–723, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.02.066. (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M. H., Huang H. R., Chu S. M., Yang P. H. & Lien R. Clinical features of newborns with gastroschisis and outcomes of different initial interventions: Primary closure versus staged repair. Pediatrics and Neonatology 51, 320–325, doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60062-9. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen M., Bratu I., Narvey M. & Rosychuk R. J. Use of paralysis in silo-assisted closure of gastroschisis. Journal of Pediatrics 161, 125–128.e121, doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.043 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil B. R., Leys C. M. & Rescorla F. J. The jury is still out: Changes in gastroschisis management over the last decade are associated with both benefits and shortcomings. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 47, 119–124, doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.029. (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.