Abstract

Owing to the lack of absolutely dated oceanographic information before the modern instrumental period, there is currently significant debate as to the role played by North Atlantic Ocean dynamics in previous climate transitions (for example, Medieval Climate Anomaly-Little Ice Age, MCA-LIA). Here we present analyses of a millennial-length, annually resolved and absolutely dated marine δ18O archive. We interpret our record of oxygen isotope ratios from the shells of the long-lived marine bivalve Arctica islandica (δ18O-shell), from the North Icelandic shelf, in relation to seawater density variability and demonstrate that solar and volcanic forcing coupled with ocean circulation dynamics are key drivers of climate variability over the last millennium. During the pre-industrial period (AD 1000–1800) variability in the sub-polar North Atlantic leads changes in Northern Hemisphere surface air temperatures at multi-decadal timescales, indicating that North Atlantic Ocean dynamics played an active role in modulating the response of the atmosphere to solar and volcanic forcing.

A lack of annually resolved climate records from the marine archive limits our understanding of oceanic processes. Here, the authors present a millennial-length, annually-resolved and absolutely-dated marine δ18O record from the shells of marine bivalves and offer insight into North Atlantic climate dynamics.

The climate of the last 1,000 years is characterized by the gradual pre-industrial cooling of the Northern Hemisphere associated with the Medieval Climate Anomaly-Little Ice Age (MCA-LIA) transition1 and the onset of modern warming2. Over these timescales, natural temperature variability has been linked to interactions between fluctuations in total solar irradiance (TSI)2,3, volcanic aerosols2,4 and internal climate system mechanisms (for example, ocean heat storage and transport5). With climate model simulations suggesting a significant slowdown in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, in response to anthropogenic forcing over the twenty-first century6, there is a pressing need to provide a more robust quantitative assessment of the role changes in the North Atlantic Ocean dynamics have played in the evolution of the climate system during the recent past.

Our current understanding of past climate fluctuations is largely derived from instrumental time series7,8, numerical climate models (for example, see ref. 9) and robustly dated well-calibrated proxy archives (for example, dendrochronologies10,11, ice cores12,13, corals14 and speleothems15) at high frequencies (inter-annual) and ocean sediment archives at lower resolutions (multi-decadal to centennial)16,17. These records have highlighted the inherent complexities in the ocean–atmosphere system with TSI3 and volcanic aerosols2,4,18 acting as top–down forcings driving ocean and atmosphere variability, coupled with internal variability and feedback mechanisms within the ocean acting as bottom-up drivers modulating the atmospheric climate response19. However, the interaction between ocean dynamics (such as sea surface temperature (SST), seawater density, surface circulation and overturning circulation strength) and atmospheric variability remain poorly characterized. The difficulty in constraining the role of coupled ocean–atmosphere mechanisms in climate variability to a large extent results from the limited length of oceanographic instrumental time series7,8 and the low temporal resolution and dating uncertainties associated with marine sediment archives. These issues hinder the identification of causal relationships through for example lead–lag analysis. Despite these challenges, evidence derived from marine proxy records has indicated that there were broad scale changes in the North Atlantic dynamics over the last millennium. For example, during the MCA-LIA transition, analyses of foraminifera from the Straits of Florida indicate the strength of the Gulf Stream and associated heat transport reduced by ca. 10% (ref. 20). Similarly, regional marine radiocarbon reservoir (ΔR) determinations from long-lived bivalves suggest an increase in the proportion of Arctic water entrained onto the North Icelandic shelf21 at this time and reconstructions derived from coralline algae22 and sedimentary biomarker records23 suggest a synchronous increase in Arctic and Icelandic sea-ice extent. Finally, radiocarbon determinations from deep sea benthic foraminifera also indicate changes in the deep-water composition of the Atlantic24, coincident with these upper ocean shifts. These studies demonstrate that variability across the North Atlantic marine environment was synchronous, within the temporal uncertainties, with the gradual reduction in Northern Hemisphere surface air temperature (NHSAT) over the MCA-LIA. However, the resolution and lack of absolute dating of all of these proxy records preclude the assessment of whether variability in the marine environment was playing an active role in driving the changes in NHSAT over the MCA-LIA transition, because they are not suitable for detailed lead–lag analysis. These constraints present a clear challenge to understanding the role ocean dynamics play in the wider climate system.

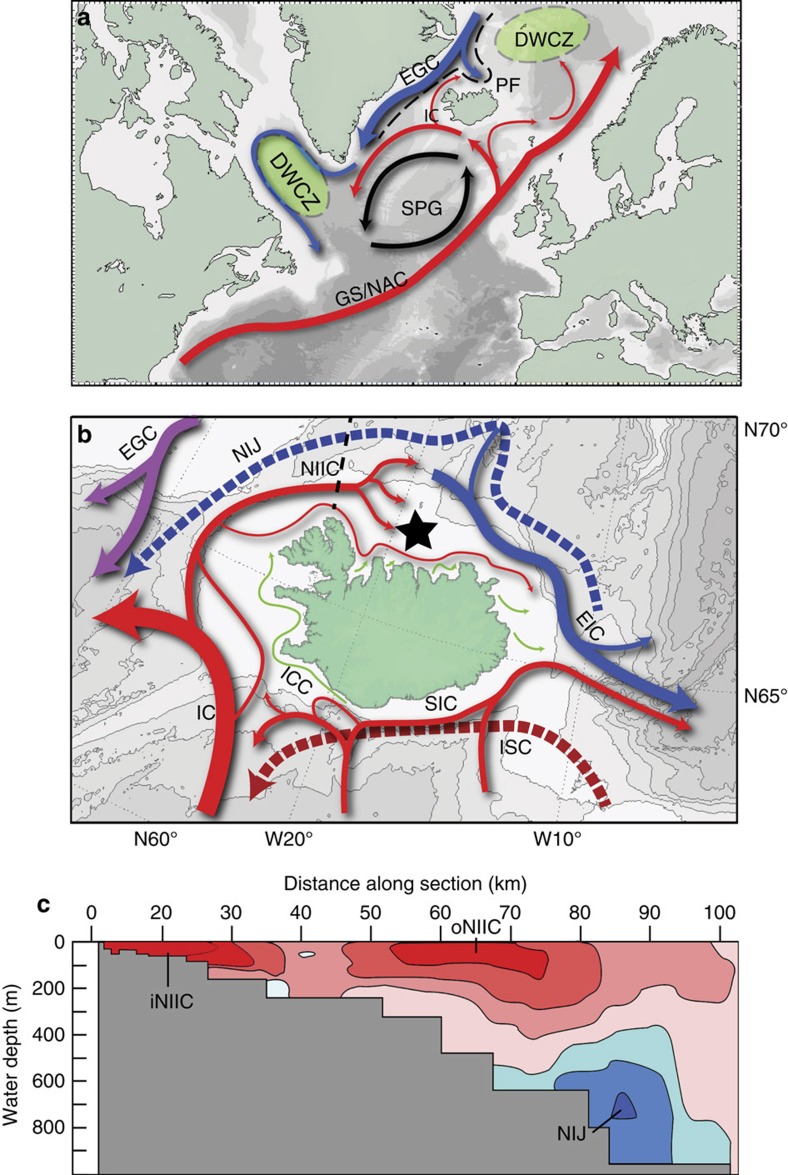

Here we report a new 1,048-year precisely dated, annually resolved marine oxygen isotope record (δ18O-shell) that spans the entirety of the last 1,000 years (AD 953–2000). This high-resolution record facilitates lead–lag analysis of high-frequency climate variability occurring across the ocean and atmosphere beyond the observational era. The δ18O-shell record is derived from the δ18O composition of aragonite sampled from the annually formed growth increments in the shells of the long-lived marine bivalve mollusc Arctica islandica collected from the North Icelandic shelf (66° 31.59′ N, 18° 11.74′ W; shells collected from 80 m water depth25; Fig. 1). This location and water depth situates the shells within the inner North Icelandic Irminger Current (NIIC; Fig. 1). This oceanographic setting is ideally situated for the examination of the role that ocean dynamics play in driving wider climate variability, reflecting the interplay between two distinct water masses: the relatively warm and saline Subpolar Mode Water (SPMW) and the cool and fresh Arctic Intermediate Water (AIW). Approximately 5–10% of the ∼10–19 Sv (1 Sv=106 m3 s−1) of SPMW water and associated heat flux, transported north in the Irminger Current, flowing as part of the sub-polar gyre, separates in the southern Denmark Strait and forms the clockwise flowing NIIC (Fig. 1 and refs 26, 27). As the NIIC flows along the North Icelandic shelf large amounts of polar AIW waters are entrained, increasing the net volume transport of the outermost branch of the NIIC from 1.1 to 2 Sv (55% SPMW/45% AIW)27. However, the somewhat weaker (∼0.3 Sv) inner NIIC retains its SPMW characteristics as it follows the inner North Icelandic shelf eastward at water depths of up to ∼100 m (Fig. 1c)27.

Figure 1. Maps of the modern surface currents of the North Atlantic and Icelandic shelf.

(a) North Atlantic circulation and (b) North Icelandic shelf circulation pattern. Arrows shown in blue correspond to cool and relatively fresh Arctic-sourced waters; arrows shown in red are warm and saline Atlantic-sourced waters; dashed lines correspond to deep currents whilst the solid arrows denote surface currents. The dashed black line in a refers to the approximate position of the North Atlantic Polar Front. The dashed black line in b refers to the depth transect shown in c. The star denotes the location of the shell sampling site (80 m water depth 66° 31.59′ N, 18° 11.74′ W). (c) Depth transect across the North Icelandic shelf indicating the direction of flow of each of three dominant water currents at this locality. Red colours indicate an easterly flow whilst blue indicates a westerly flow. DWCZ, deep water convection zones; EGC, East Greenland Current; EIC, East Icelandic Current; GS/NAC, Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current; IC, Irminger Current; iNIIC, inner NIIC; ISC, Icelandic slope current; NIIC, North Icelandic Irminger Current; NIJ, North Icelandic Jet; oNIIC, outer NIIC; PF, polar front; SIC, South Icelandic Current. (b,c) Adapted from ref. 27 and the base map from ref. 43.

Results

Oxygen isotope time series

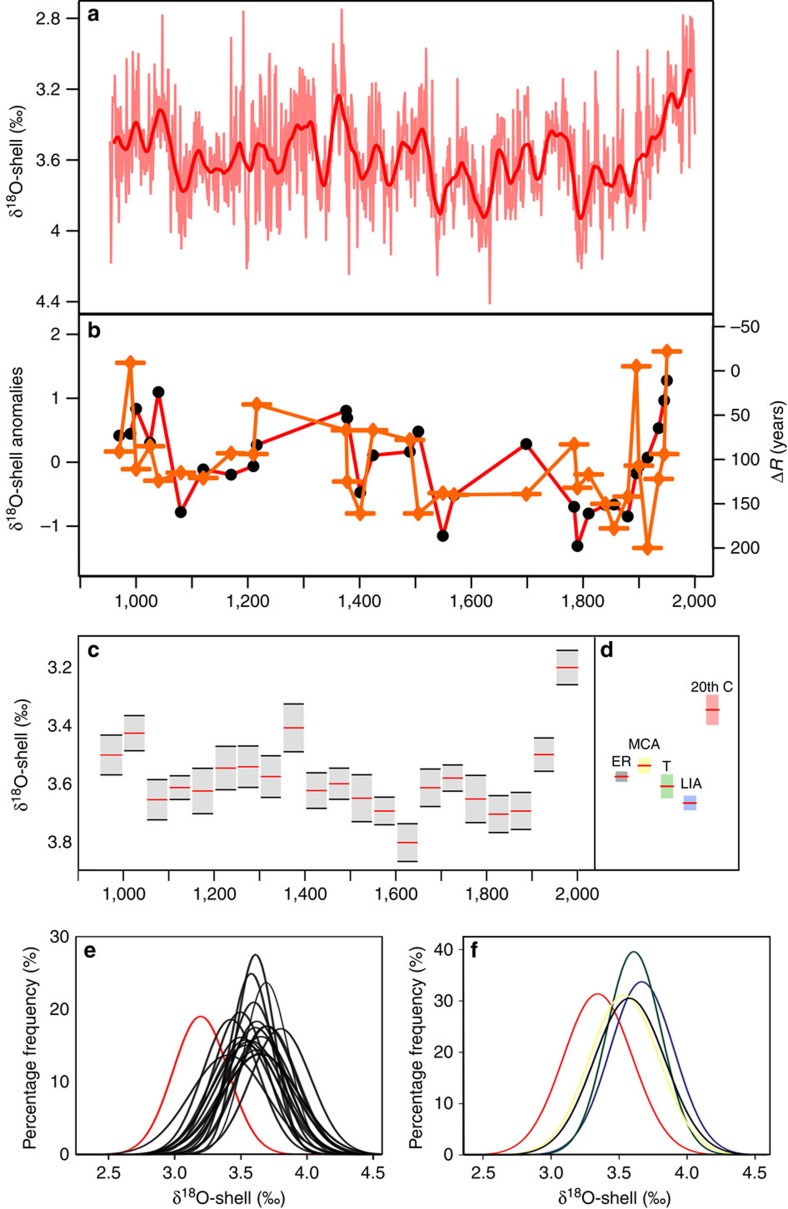

The age of each δ18O sample comprising the 1,048-year δ18O-shell record is derived from an absolutely dated growth increment width master chronology constructed using cross-dating methods derived from dendrochronology21,28. In total, the δ18O-shell series is constructed from the analysis of 1,492 samples reflecting either single δ18O measurements from individual years within the growth increment width master chronology or the arithmetic mean in years represented by replicate sample analyses (Supplementary Fig. 2). The growing season of the A. islandica shells is defined using sub-annually (sub-incremental) resolved δ18O analyses over the period 1960–1976 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Examination of the sub-annually resolved δ18O analyses relative to local instrumental seawater temperature (SWT) observations and the relative sampling position within each increment indicates that 60–80% of the shell growth takes place between June and late September each year, with slower rates of growth occurring during spring (April to June) and autumn (September to October). The annually resolved δ18O-shell series (Fig. 2) contains a gradual increase in δ18O ratios over the period AD 953–1891 (±18 years)29 after which there is a rapid transition to lower values. Examination of the mean and percentage frequency distribution of these data over the key periods of the last 1,000 years (MCA, LIA and the twentieth century) and in non-overlapping 50-year bins (Fig. 2c–f) indicates that both the whole twentieth century and the period from 1951 to 2000 are represented by δ18O-shell values that are significantly lower than any other period over the last 1,000 years (P<0.001; for full T-test results, see Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. The δ18O-shell series and ΔR record.

(a) The annually resolved δ18O-shell series (pink line) plotted with a 30-year loess first-order low-pass filter (thick red line). (b) The North Icelandic marine reservoir age series21 (orange line with diamonds and bar) and the δ18O-shell values for the corresponding years (red line with black dots). The δ18O-shell series was low-pass filtered to match the temporal resolution of the ΔR record. (c) Mean δ18O-shell values plotted with associated 95% confidence intervals calculated over 50-year bins (with zero years overlap) and (d) mean δ18O-shell values calculated over the twentieth century (20th C; red bar), the Little Ice Age (LIA; blue bar), the MCA-LIA transition (T; green Bar), the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA; yellow bar) and the entire isotope record (ER; grey bar). (e,f) Percentage frequency distributions of the δ18O-shell record calculated over (e) 50-year bins (red line corresponds to 1951–2000, whereas the black lines correspond the previous 50-year bins) and (f) the twentieth century (red line), the Little Ice Age (blue line), the MCA-LIA transition (green line), the Medieval Climate Anomaly (yellow line) and the entire isotope record (black line).

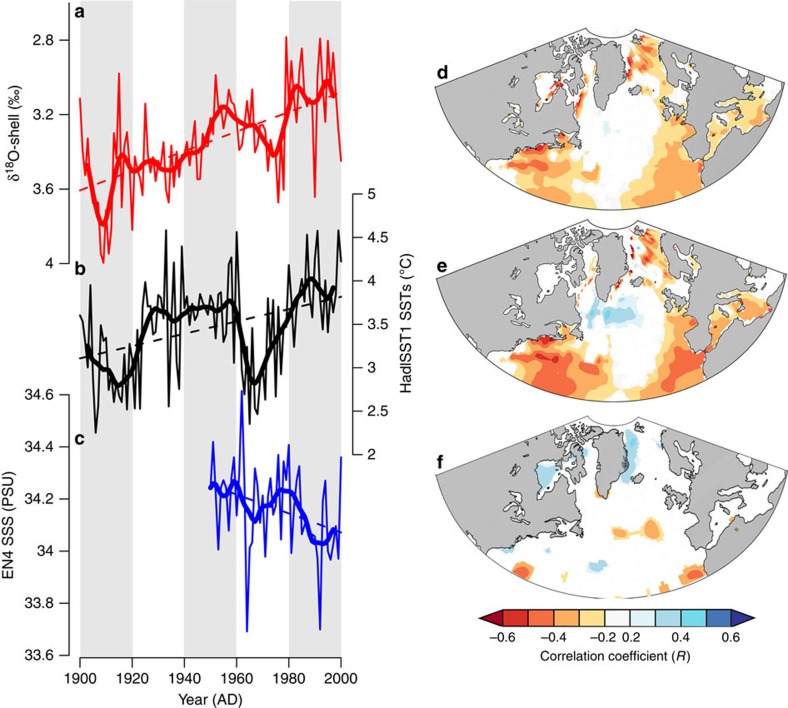

Calibration against instrumental time series

The δ18O-shell data were compared with modern temporal and spatial oceanographic instrumental data, to determine the dominant environmental driver of variability (SWT or salinity) and its geographical extent (Fig. 3). The temporal and spatial correlation analyses identified significant correlations between the δ18O-shell record and SST (annually resolved correlation r=−0.26, P<0.1, calculation period 1900–2000) and sea surface salinity (SSS; annually resolved correlation r=0.43; P<0.1, calculation period 1950–2000). The spatial correlation analyses show that the δ18O-shell record correlates significantly (P<0.01) with mean growing season (April to October) SSTs over much of the Greenland, Iceland and Norwegian Sea, whereas weaker, yet still significant (P<0.1), correlations are also identified over wider regions of the North Atlantic incorporating portions of the Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current trajectory. Analysis of the δ18O-shell record with the preceding winter (December to February) SSTs strengthens the spatial correlation across the wider regions of the North Atlantic. These spatial correlations also indicate a significant positive correlation between sub-polar gyre SST and the δ18O-shell record over the preceding winter months (Fig. 3e). The increased strength of these correlations probably reflects the propagation time for variability in these portions of the North Atlantic to influence the waters transported by the NIIC at the sampling site. In addition, although the spatial correlation analyses indicate a significant correlation between the δ18O-shell record and SSS on the North Icelandic shelf, the absence of a significant spatial correlation between the δ18O-shell data and SST in this region is likely to be associated with differences between SST and bottom (∼80 m water depth) SWTs recorded by A. islandica.

Figure 3. Spatial and temporal examination of the δ18O-shell data with instrumental oceanographic time series.

(a–c) Plots of the annual (thin lines) and 10-year low-pass-filtered (thick lines) (a) δ18O-shell, (b) HadISST1 gridded SST data and (c) EN4 gridded SSS. (d,e) Spatial correlations between the δ18O-shell and HadISST1 SST over (d) the growing season (March to October) and (e) the preceding winter (December to February). The correlations are calculated over the period 1870–2000. (f) Spatial correlations between the δ18O-shell and the EN4 SSS gridded SSS data set. Correlations calculated over the period 1950–2000. All correlations shown are significant with a P<0.1. Instrumental displayed in b,c are derived from a 10° by 20° grid box (65–75°N 10–30°W) north of Iceland. Spatial correlations generated using the KNMI climate explorer (https://climexp.knmi.nl/).

Temporal examination of the correlation coefficients identified using the spatial correlation analyses indicates that SST variability on the North Icelandic shelf contains a weakly significant correlation with the annually resolved δ18O-shell data (r=−0.26, P<0.1). However, the SST data explain 36% of the variance (P<0.05) in the 10-year loess first-order low-pass-filtered δ18O-shell record over the twentieth century and 55% of the variance over the period from 1950 to 2000. Examination of the correlations calculated using linear detrended data indicates that the δ18O-shell data contains reduced skill at reconstructing inter-annual variability (linear detrended annually resolved r=−0.04, P>0.1), but is sensitive to decadal scale SST variability over the twentieth century (linear detrended 10-year low-pass-filtered r=−0.37, P<0.1). Owing to a lack of instrumental data, it is not possible to evaluate whether the reduction in skill is due to a lack of sensitivity to SSTs or due to differences between SST and bottom water temperatures. Linear regression analysis of the δ18O-shell record and North Icelandic shelf SSS data indicates a significant positive correlation with the annually resolved data over the period from 1950 to 2000 (r=0.43, P<0.01), suggesting that salinity variability explains 18% of the annually resolved variability in the δ18O-shell record. Examination of correlations calculated using linear detrended annually resolved and 10-year loess first-order data indicate consistent correlations between the δ18O-shell record and SSS data, suggesting that the δ18O-shell record is likely to be sensitive to both inter-annual and longer-term SSS variability (annually resolved r=0.43, P<0.01; 10-year low-pass-filtered r=0.46, P=0.25; linear detrended annually resolved r=0.38, P<0.05; linear detrended 10-year low-pass-filtered r=0.23, P=0.6; all correlations calculated over the period from 1950 to 2000). Further analyses of the coherence between the δ18O-shell record and combined SST and SSS variability using multiple linear regression indicate that the combined SST and SSS variability can explain 19% of the variance in the annually resolved and 63% of the variance in the decadal δ18O-shell variability over the period 1950–2000 (P<0.01). The level of correlation identified using the multiple regression analyses is stable using the linear detrended SSS and SST data (r=0.40 and 0.78 for annually resolved and decadal smoothed linear detrended data, respectively), indicating the δ18O-shell record is sensitive to both inter-annual and multi-decadal scale variability in combined SSTs and SSSs. We therefore consider our δ18O-shell series to qualitatively represent seawater density on the North Icelandic shelf, which is the combined product of SWT and salinity30.

Discussion

Linear regression indicates a weakly significant correlation between variability in our δ18O-shell record and the North Icelandic shelf regional marine radiocarbon reservoir ages (ΔR)21 (r=−0.39±0.29, P=0.056; Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs 4 and 5). The ΔR data represent the regional difference from the global mean ocean radiocarbon reservoir age, which on the North Icelandic shelf also reflects the degree of entrainment of relatively old (with respect to carbon) polar AIW into the younger SPMW transported by the NIIC21,25. The coherence between the North Icelandic shelf ΔR21 and δ18O-shell series indicates that during periods characterized by relatively older (younger) ΔR values, due to a relative increase (decrease) in the proportion of AIW within the NIIC, the δ18O composition of the shell aragonite increases (decreases), indicative of an increase (decrease) in the density of the ambient seawater bathing the site.

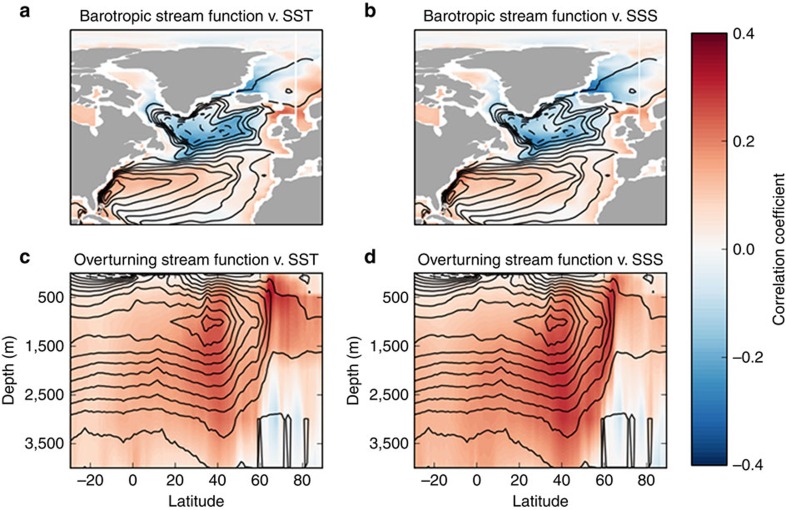

It has previously been proposed that changes in the strength of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation are linked to variability in the degree of AIW entrainment into the NIIC and therefore the SPMW/AIW composition of the waters influencing the North Icelandic shelf21,31,32. Although instrumental oceanographic observations are currently of insufficient length to evaluate this suggestion, evidence derived from an ensemble of 17 Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5 (CMIP5) unforced pre-industrial control simulations suggests that changes in SST and SSS on the North Icelandic shelf correlate significantly with inter-annual and multi-decadal scale variability in North Atlantic barotropic and overturning stream functions (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The stability of these correlations, irrespective of the smoothing function applied, indicates that the SST and SSS (along with the associated seawater density) variability on the North Icelandic shelf are sensitive to changes in Atlantic circulation dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 4. Model analyses of the coherence between North Icelandic SST and SSS variability and North Atlantic circulation.

Correlation between annual North Icelandic SSTs against (a) barotropic stream function and (c) overturning stream function, and SSS against (b) barotropic stream function and (d) overturning stream function, in the North Atlantic derived from an ensemble CMIP5 preindustrial control simulation. The solid black lines show the time-mean stream functions.

To better constrain the uncertainties associated with the role that the ocean system plays within the wider climate system, it is necessary to assess quantitatively the degree to which ocean variability is related to external forcing mechanisms. To do this we compare the new δ18O-shell record to millennial climate forcing time series (volcanics, TSI and modelled combined forcings), NHSAT, derived from a composite dendrochronological record11, and Greenland air temperatures, derived from an ice core stack13.

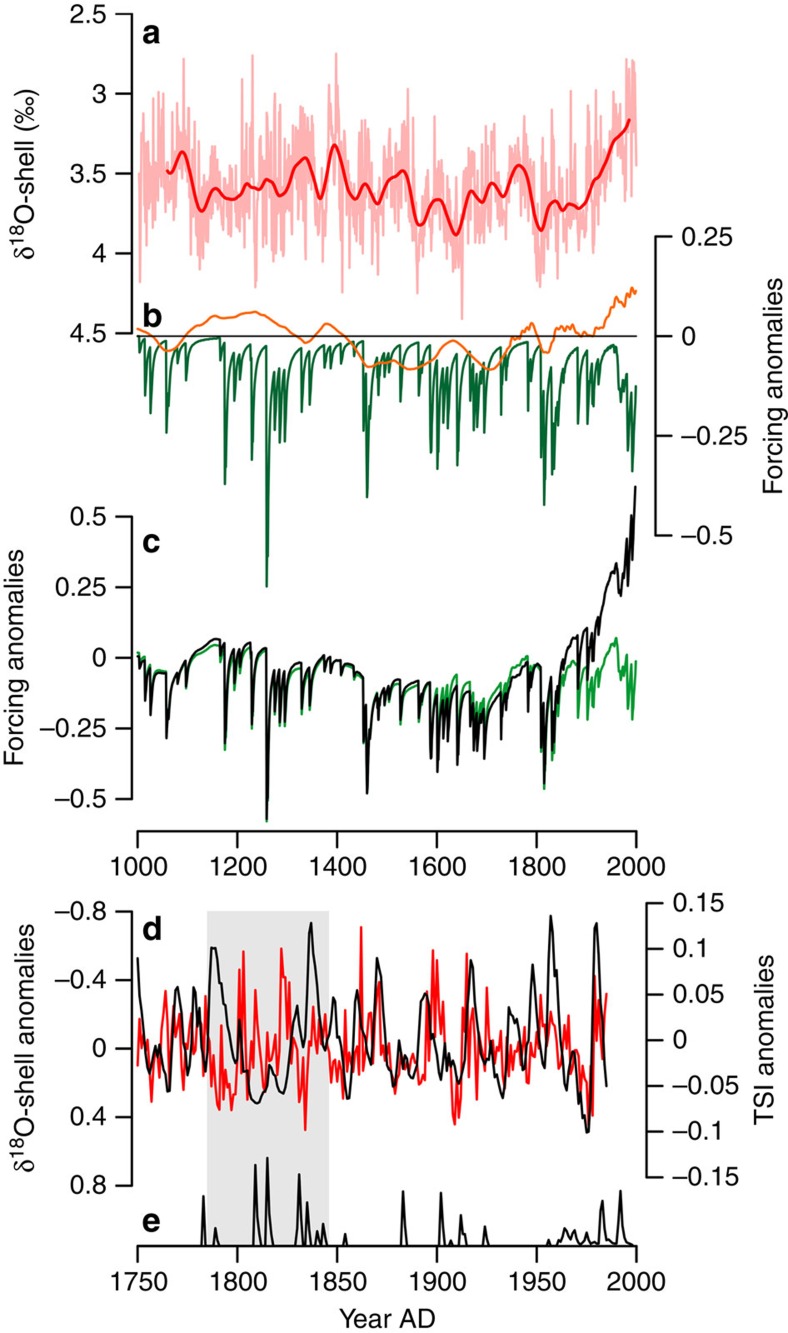

Estimates of past TSI variability can be characterized into two distinct intervals, the observed period (∼AD 1750 to present) and the proxy-generated reconstruction period (years before ∼AD 1750)2,33. The proxy reconstruction of TSI, derived from radiogenic isotopes (10Be and 14C) is typically deficient in the high-frequency component of the solar variability spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 6). The observed TSI period however captures both the longer-term trends, such as the gradual increase in TSI since the end of the Maunder Minimum in the early AD 1700s and high-frequency variability such as the 11-year sunspot cycle2,33. We identify a significant correlation between the δ18O-shell series and TSI over the last 1,000 years (annual resolution r=0.27, P<0.05; decadal resolution r=−0.34, P<0.05). The correlation is significantly stronger over the observed period of AD 1750–1997 (r=−0.68 P<0.05), suggesting that TSI variability may explain up to 47% of the variance in seawater density over this period. The coherence spectra of the correlations show that the increase in correlation over the observed period is not likely to be due to low-frequency variability, as similar levels of coherence were identified across these portions of the spectrum for both the observed period and the entire millennium (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, over the observed period, significant correlations (r=−0.39, P<0.01) were identified within the high-frequency domains (using 50-year loess first-order high-pass-filtered data; Fig. 5d). This high-frequency component of the solar spectrum is unrepresented in the proxy reconstruction derived from radiogenic isotopes (Supplementary Fig. 7). Although these analyses and several previous studies (e.g. refs 16, 17) indicate that solar variability probably plays a role as a natural driver of marine variability, the presence of several large volcanic eruptions over the observed period and the lack of any reliable proxy for high-frequency solar variability over earlier parts of the last millennium complicates the interpretation of the role of solar variability in driving oceanographic variability.

Figure 5. The δ18O-shell series and climate forcings.

Comparison between (a) the inverted δ18O-shell anomalies (annually resolved and 50-year loess low-pass-filtered data shown by the pink and red lines, respectively) with (b) individual climate forcing indices (TSI and volcanics shown by the orange and green lines, respectively), and (c) combined natural forcings (solar and volcanics; green line) and combined total forcing (solar, volcanics, greenhouse gases, aerosols; black line). (d) Plot of the 50-year loess first-order high-pass-filtered TSI (black line) and inverted δ18O-shell anomalies (red line) over the period AD 1750–1997. (e) Timing of volcanic eruptions over the AD 1750–1997 period. The grey box highlights the 2 consecutive 30 periods following the Laki (1783) and Tambora (1815) volcanic eruptions, which probably dominate the climate signal over this period. Climate forcing data from Crowley2.

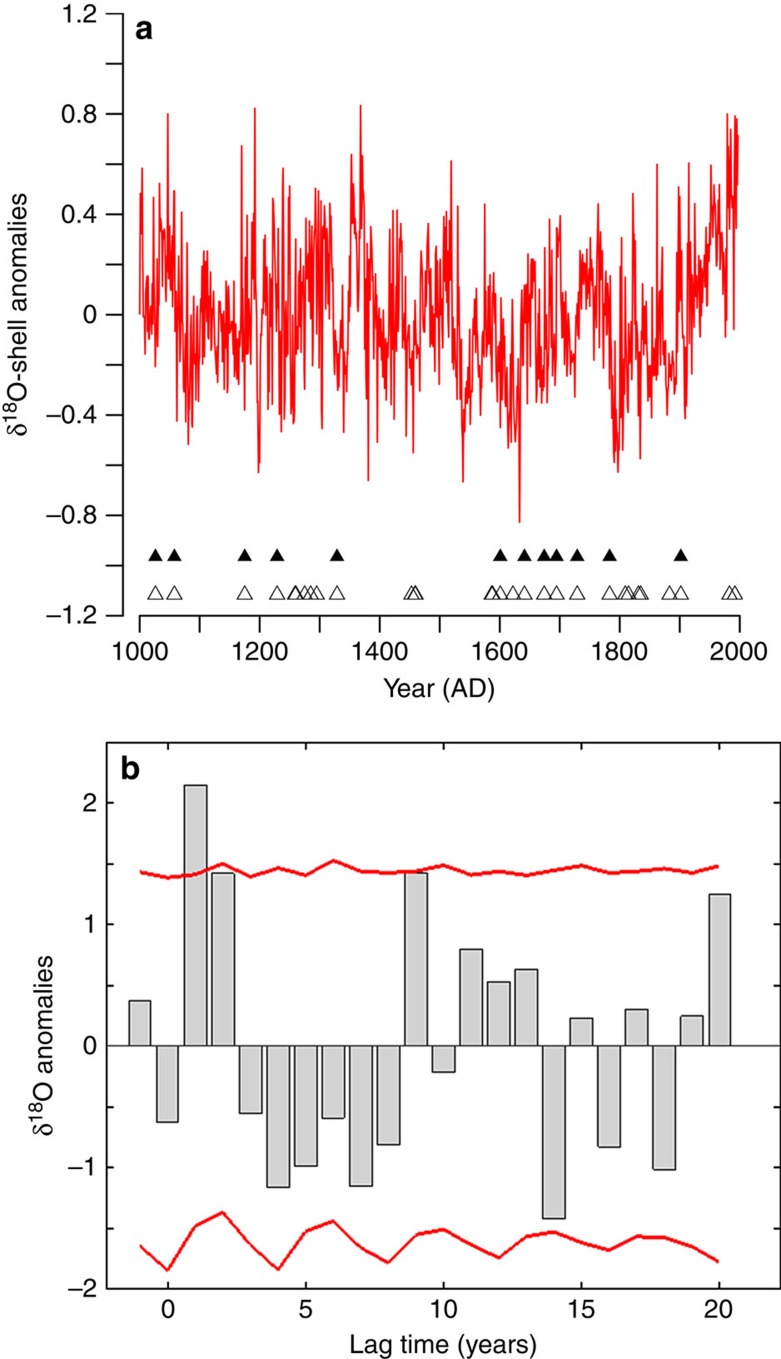

We examined the influence of volcanic aerosols injected into the stratosphere, a consequence of large explosive volcanic eruptions, on the δ18O-shell series by conducting a superposed epoch analysis (SEA34; Fig. 6). We find a significant positive shift in the δ18O-shell anomalies in the first (P<0.05) and second (P<0.1) year following volcanic eruptions. This result is consistent using two approaches to the SEA (see Supplementary Fig. 7). Although evidence from Swingedouw et al.35 suggest that volcanic eruptions can have an influence on the North Atlantic that spans several decades, as part of a bi-decadal oscillation, our analyses only indicates a significant response of the marine system in the two years following the largest eruptions of the last 1,000 years. The bi-decadal oscillation present in the SEA analyses of the δ18O-shell series, although similar in amplitude and timing to the previously suggested North Atlantic circulation variability associated with volcanic forcing, is not statistically significant35. These results indicate that seawater densities north of Iceland show a rapid response to volcanic forcing with an immediate decrease in seawater density over the two years following the eruption. The significant response of the δ18O-shell series to the volcanic forcings probably explains the drop in correlation observed between the δ18O-shell series and TSI over the period from 1783 to 1843. This period is characterized by three large eruptions, Laki in 1783, an unknown eruption in 1809 and Tambora in 1815, which probably drive the climate signal over this interval.

These analyses indicate that both the TSI and volcanic aerosol forcings are playing a major role as natural drivers of high-frequency (inter-annual to multi-decadal) marine variability on the North Icelandic shelf. However, the comparison between the δ18O-shell record and the combined climate forcing index (using TSI, volcanics, stratospheric aerosols and greenhouse gases; Fig. 5c and ref. 2) suggests that, even with the gradual 0.01% increase in TSI since the Maunder Minimum3, natural climate forcings alone cannot account for the significant change in δ18O-shell values over the industrial period.

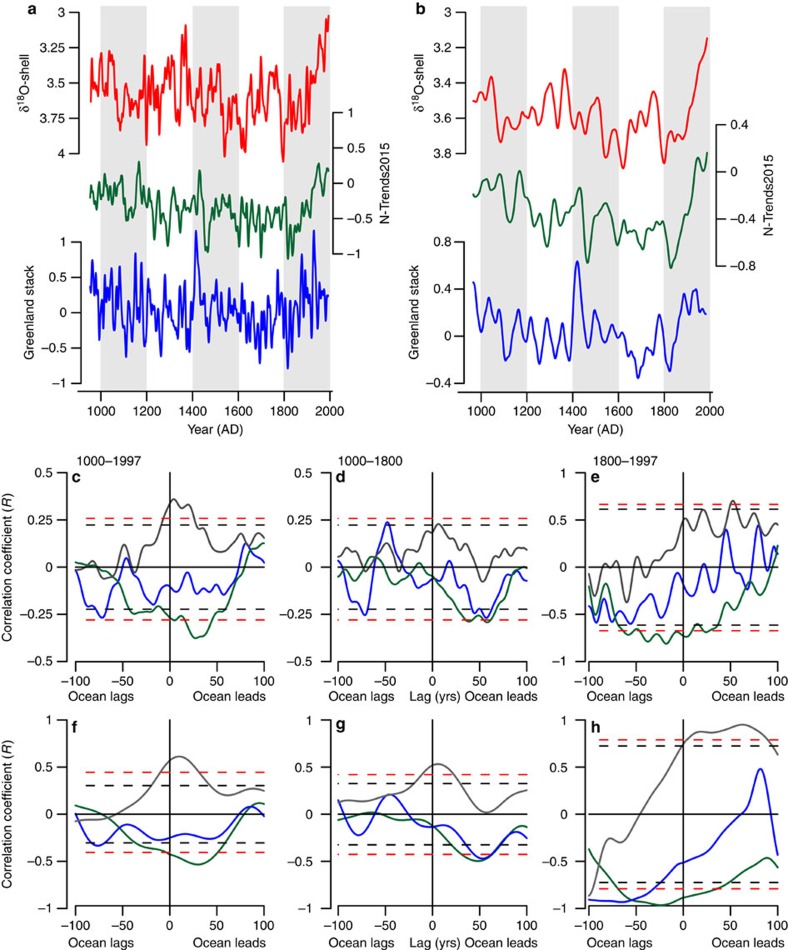

Given the precisely dated nature of the δ18O-shell series and its sensitivity to sub-polar North Atlantic variability, these data present the first opportunity to assess quantitatively the previously untestable hypothesis that ocean circulation dynamics might have played an active role in driving the key climate transitions of the last 1,000 years. We have therefore examined the timing of variability in the absolutely dated δ18O-shell series relative to reconstruction of NHSAT, derived from a composite dendrochronological series11 and individual tree ring series, and Greenland air temperatures, derived from an ice core stack13, over the last 1,000 years (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Figs 9 and 10). Lead–lag correlation analysis, conducted between the normalized δ18O-shell anomalies and NHSAT and Greenland air temperatures, indicates that over the pre-industrial period (AD 953–1800) multi-decadal to centennial frequency atmospheric temperature variability lagged changes in the δ18O-shell seawater density anomalies by 40±30 years (peak correlation r=−0.27 and −0.29, P<0.05 against NHSAT and Greenland air temperatures, respectively). Such a temporal offset is beyond the dating uncertainty of these records. The lead of North Icelandic shelf hydrographic variability over both the NHSAT and Greenland air temperature series strongly indicates that ocean variability played an active role in driving the major pre-industrial climate variability of the past 1,000 years. The coincident variability observed in the Greenland air temperature and wider NHSAT records argues against the possibility that the ocean lead we observe is driven by regional changes in atmospheric circulation patterns.

Figure 7. Lead-lag correlation analysis between the inverted δ18O-shell anomalies and NHSATs.

NHSATs derived from a composite dendrochronological series11 and Greenland air temperatures derived from a stack of Greenland ice cores13. (a) Ten-year and (b) 50-year loess first-order low-pass-filtered δ18O-shell anomalies (red lines), Northern Hemisphere air temperatures (green lines) and Greenland air temperatures (blue lines). (c–h) Lead–lag correlation plots calculated between the δ18O-shell series and Northern Hemisphere air temperatures (green lines), the δ18O-shell series and Greenland air temperatures (blue lines), and Northern Hemisphere air temperatures and Greenland air temperatures (grey lines). The correlations are calculated over three periods. (c,f) Correlations calculated over the entire millennium. (d,g) Correlations calculated over the pre-industrial period (AD 1000–1800). (e,h) Correlations calculated over the industrial period (AD 1800–1997). Data used in the correlations in plots c–e were 10-year loess first-order low-pass filtered, whereas the data used to calculate the correlations in plots f–h were 50-year loess first-order low-pass filtered. The dashed black and red lines in plots (c–h) represent the respective 90 and 95% significance levels calculated using 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations using the Ebisuzaki method37.

The results of the lead–lag analysis of the reconstructions are further validated using the available ensemble of CMIP5 unforced pre-industrial control simulations (Supplementary Fig. 12). The CMIP5 preindustrial control simulations contain no external forcing; thus, all climate variability is internally generated9. Lead–lag analysis of the modelled North Icelandic shelf seawater density and NHSAT show that, consistent with the proxy records, the ocean variability leads the atmosphere by 10±10 years (Supplementary Fig. 12)18,19,35. The offset in the magnitude of ocean–atmosphere lag between model and real-world data are likely to be a result of differences in the detail of the surface and meridional circulations between models, and between the models and reality.

In comparison with the preindustrial interval, the modern trends (AD 1800–2000) in the NHSAT records relative to the δ18O-shell anomalies, coupled with the lead–lag analyses, suggests a reversal of the pre-industrial ocean–atmosphere coupling over the industrial period (AD 1800–2000) with changes in ocean dynamics more closely coupled in time, or lagging, increases in atmospheric surface air temperatures (Fig. 7). The close coupling identified by the proxy records over the industrial period is in agreement with the timing of coupling observed between instrumental NHSAT and sub-polar North Atlantic SSTs over the period AD 1880–2015 (Supplementary Fig. 11). The shift in coupling between the pre-industrial and industrial time periods is likely to be driven by a change in the balance between top-down and bottom-up forcings19.

The lead–lag correlations, coupled with the correlation of the δ18O-shell data with volcanic and high-frequency TSI forcing, suggest that at higher frequencies (<20 years) the ocean–atmosphere systems is closely coupled with periodic volcanic eruptions and high-frequency solar variability (for example, the sun spot cycle) driving a rapid response in both the atmosphere and ocean systems35. The lead–lag analyses suggest that at lower frequency domains (multi-decadal to centennial) marine variability is playing an active role in driving atmospheric variability. Such a divergence in the lagged response of the ocean and atmosphere systems at different frequency domains is detectable in the modern instrumental observations. Examination of a suite of instrumental SST and NHSAT's indicates that over the twentieth century the atmosphere leads the ocean system at lower frequencies (multi-decadal; see Supplementary Fig. 11), probably driven by the faster response of the atmosphere to the warming influence of greenhouse gases. However, examination of the high-frequency variability (20-year high-pass-filtered data; Supplementary Fig. 11) implies a tighter coupling with high-frequency forcings/feedback mechanisms causing synchronous variability across both the ocean and atmosphere systems. These data suggest that during the pre-industrial period internal variability and feedback mechanisms within the North Atlantic substantially mediate the response of the climate system to top–down forcing (TSI, volcanic, atmospheric aerosols and greenhouse gases). Although, over the industrial period these data imply that internal oceanic mediation of top–down forcing has been overcome by the rate and nature of the NHSAT increase forced by increasing greenhouse gas concentrations.

These findings have implications for the interpretation of the modern climate system, as they highlight the problems that can result from using short modern oceanographic instrumental observations as a representative baseline of natural climate variability. Such records, although capturing a component of natural variability, are probably dominated by the anthropogenic signal. Furthermore, our data demonstrate shortcomings in methodologies that attempt to extend the modern instrumental ocean observations using absolutely dated records derived from terrestrial proxy networks (for example, see ref. 36). With the reconstructed reversal in the timing of ocean–atmosphere coupling, these results question the ability of terrestrial archives alone to reconstruct ocean variability and highlight the need to use independent absolutely dated marine archives to characterize the role ocean dynamics play in the global climate system.

The δ18O-shell record presented here provides the first precisely dated annually resolved record of past marine variability that spans the entire last 1,000 years. It provides a long-term baseline for the state of the North Atlantic coupled climate system and demonstrates that the role played by the ocean in naturally forced climate variability should be a key focus if we are to realise the societally crucial step forward in near-term climate prediction.

Methods

Shell collection and age model

Live and dead A. islandica shell material was collected from 80 m water depth, from the North Iceland shelf (Grimsey, 66° 31.59′ N, 18° 11.74′ W); full details of the shell collection are provided in (ref. 25). An absolutely dated master shell chronology was constructed by cross-dating the live and dead collected shell material using techniques derived from dendrochronology. The statistical cross-dated ages were validated using accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon dating. Full details of the construction of the North Iceland shelf growth increment width chronology are available in refs 21, 25, 28. Aragonite calcium carbonate samples were micro-milled from known age A. islandica growth increments using a Merchantek New Wave Micro-mill at annual resolution over the period AD 953–2000 and at sub-annual resolution over periods of the twentieth century. All temporal correlations reported were calculated using the Ebisuzaki Monte Carlo method to take into account auto-correlation37.

Stable isotope analyses

Stable isotope measurements were completed using a Thermo Finnigan MAT 252 and 253 isotope ratio mass spectrometers coupled to a Kiel carbonate preparation device at Cardiff University. The isotopic results are reported as a per mil deviation from the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite scale with an external reproducibility of carbonate standards (NBS 19) better than 0.08‰ for δ18O.

Construction of the δ18O-shell series

The δ18O-shell series was constructed from the analysis of 1492 annually resolved aragonite samples. These samples originate from 21 individual shells that were previously cross-dated. Replicates were taken at each overlap between shells. Further replication was conducted over the twentieth century where replication in the chronology was strongest. The arithmetic mean was calculated in years containing multiple δ18O analyses, to construct a single series with one value per year. Supplementary Fig. 2 highlights all the years with replicated δ18O analyses. Contrary to the development of growth increment width chronologies, the δ18O-shell series requires no application of detrending methodologies as the δ18O-shell series contains no ontogenetic trends.

Sub-annually resolved δ18O analyses

Sub-annually (sub-incremental) resolved δ18O-shell samples were analysed from shells covering the latter half of the twentieth century, to determine the seasonality of growth and therefore to determine the seasonal representation of the annually resolved growth increment samples. The sub-annual δ18O-shell data were converted to SWTs using modified Grossman and Ku38 aragonite palaeotemperature equation39. The ambient water δ18O values (δ18Ow) were derived from seawater salinity timeseries using the North Iceland salinity mixing line equation40. These sub-annually resolved reconstructed δ18O-shell SWT were then compared with seasonal records of local SWT derived from the Grimsey oceanographic instrumental timeseries (Supplementary Fig. 3). Comparison of the observed and reconstructed SWT allowed the determination of the period of growth and the timing of the formation of the growth check. The sub-annually resolved reconstructed δ18O-shell SWT contains a range of temperatures that are coherent with SWT during the period of March through to October (Supplementary Fig. 3). Comparison of the relative drilling position within each growth increment (calculated as the percentage of total annual growth) against the corresponding time of year represented by the corresponding sub-annual δ18O-shell sample provides an estimation of the seasonal growth rate and therefore provides an estimate of the seasonal weighting of the annually resolved δ18O-shell samples (Supplementary Fig. 3C). These analyses suggest that although the majority of growth takes place during the period of June–October, the full growth season extends from March through to October. These results are in agreement with previously published records of A. islandica growth from Iceland41.

Superposed epoch analysis

The SEA approach aligns windows of the δ18O-shell record based on the timing of the selected volcanic eruptions and calculates an average of the time series. The averaging of these windows removes the relative influence of non-aligned climate forcing from the record increasing the signal to noise ratio allowing for the identification of a volcanic induced climate signal if present34. A Monte Carlo approach was used to assess the statistical significance of the identified climate signal. We performed the SEA using two approaches and compared the results. For the first approach we selected the 30 years with the highest volcanic aerosol concentrations, which probably represent the largest 30 volcanic eruptions of the last 1,000 years from the Crowley2 volcanic index. In this approach, all 30 eruptions were used regardless of whether other large eruptions occurred during the analysis interval. In the second approach we initially selected the same 30 volcanic eruptions as in the first approach, but discarded any eruption that was followed by another large eruption within the analysis window (following 20 years) similar to approaches taken by Swingedouw et al.35. This filtering process led to the analysis of 12 volcanic eruptions.

Lead–lag analysis of Northern Hemisphere SAT reconstructions

Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated over the pre-industrial (AD 1000–1800) and industrial (AD 1800–2000) period windows with lead–lags of ±100 years (1 year incremental steps). In total, 13 individual tree-ring width and multi-proxy network derived NHSAT records were used in the analysis. The raw δ18O-shell anomalies and NHSAT records were filtered using a 10-year loess first-order low-pass filter, to equalize the highest frequency variability across the records, and 50-year loess first-order low-pass filter, to examine the low-frequency components of variability. The lead–lag correlations were calculated using the 10-year and 50-year low-pass-filtered data, respectively. Significance levels for the correlations were determined using the Ebisuzaki method37.

Examination of the lead–lag analyses using an increasing smoothing function (running mean smoothing; Supplementary Fig. 10) highlights that over the pre-industrial period there is a significant correlation between the NHSATs and the δ18O-shell data with a lag of ∼50 years. However, the lead–lag correlations of the entire period show little lag. Examination of the running lead–lag correlation analysis indicates that the 50-year lagged correlation is persistent over the period AD 1200–1800 with a switch occurring over the industrial period to a negligible lag over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The running lead–lag correlations calculated between the 10-year low-pass-filtered data indicate that there is some coherence at around zero year lag; however, there is also a strong correlation at 50 years. This suggests that there is a component of variability that is tightly coupled between the ocean and atmosphere systems.

Examination of trends in the instrumental record

The ocean–atmosphere system over the modern instrumental record generally shows close temporal coupling; however, subtle differences are present at specific frequency domains. Supplementary Fig. 11 explores the timing of variability and multi-decadal (20-year low-pass-filtered data) and at high frequencies (20-year high-pass-filtered data). The low-pass-filtered data clearly show that the onset of the early- and mid-twentieth century (∼1910 and ∼1960) warming phases in the atmosphere precede the warming in the ocean by around a decade. However, over the same intervals the ocean and atmosphere system shows a close coupling in the high-frequency domain with the inter-annual temperature anomalies remaining coherent over the entire record (Supplementary Fig. 11). These data therefore support the results from the proxy analyses that the temporal alignment of the ocean–atmosphere coupling can differ across different temporal frequency domains.

CMIP5 pre-industrial control simulation analysis

SST, SSS and surface air temperature data were extracted from the available CMIP5 full pre-industrial control simulations (Supplementary Note 1). The selected model fields were re-gridded onto a 180 × 360° grid using bilinear interpretation. Mean SST and SSS data, calculated within each model across the North Iceland region (25.0°W to 10°W, 65°N to 70°N), were used to calculate North Iceland seawater densities using the UNESCO 1983 algorithm42. These data were compared with the model-derived mean NHSAT data using the same lead–lag methodology that was applied to the δ18O-shell and dendrochronological air temperature proxy series (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Data availability

Data are available through the NOAA climate data centre (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo/study/20448)

Additional information

How to cite this article: Reynolds, D. J. et al. Annually resolved North Atlantic marine climate over the last millennium. Nat. Commun. 7, 13502 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13502 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-12, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References

Figure 6. SEA of the δ18O-shell series.

The SEA was conducted between the 12 largest volcanic eruptions of the last 1,000 years and the annually resolved δ18O-shell series. (a) The annually resolved δ18O-shell series (red line); the triangles indicate the timing of the 12 (black filled triangles) and 30 (open triangles) largest volcanic eruptions, respectively. (b) SEA analysis of the δ18O-shell series using the 12 largest eruptions. The grey bars indicate the mean δ18O-shell series anomalies in over the 12 analysis windows. The red lines indicate the 95% significance level derived using a bootstrapping methodology.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the RV Bjarni Sæmundsson (Cruise No. B05-2006). This work was supported by the NERC-funded ULTRA project (Grant Number NE/H023356/1), NERC-funded CLAM project; (Project No. NE/N001176/1) and EU Millennium Project (Project number 017008). This study is a contribution to the Climate Change Consortium for Wales (C3W). We thank Brian Long (Bangor University) and Dr Julia Becker (Cardiff University) for their technical support, and Dr Manfred Mudelsee for his assistance with the trend analysis. We thank Dr Jessica Tierney and an anonymous reviewer for providing the constructive comments in the reviewing process.

Footnotes

Author contributions J.D.S., C.A.R. and I.R.H. conceived the study. D.J.R. led the development of the stable isotope series, conducted the data analysis and led the writing of the manuscript. I.R.H. and A.N. contributed to the generation of the stable isotope series. P.H. assisted in the model analyses. A.D.W. and P.G.B. contributed expertise on the north Iceland sclerochronology and climate dynamics. J.H., J.E. and K.L.K. contributed expertise on the radiocarbon record and oceanography. All authors contributed towards the data interpretation and generation of the manuscript.

References

- Mann M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly. Science 326, 1256–1260 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley T. J. Causes of climate change over the past 1000 years. Science 289, 270–277 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilber F., Beer J. & Fröhlich C. Total solar irradiance during the Holocene. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, doi:; DOI: 10.1029/2009gl040142 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robock A. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 38, 191–219 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Rahmstorf S. Ocean circulation and climate during the past 120,000 years. Nature 419, 207–214 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittner A., Latif M. & Schneider B. Model projections of the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation for the 21st century assessed by observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, doi:; DOI: 10.1029/2005gl024368 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. M. & Reynolds R. W. Improved extended reconstruction of SST (1854–1997). J. Climate 17, 2466–2477 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell J. W. & Trenberth K. E. Global sea surface temperature and analyses: multiple problems and their implications for climate analysis, modeling, and reanalysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 80, 2661–2678 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. E., Stouffer R. J. & Meehl G. A. An overview of cmip5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Moberg A., Sonechkin D. M., Holmgren K., Datsenko N. M. & Karlen W. Highly variable Northern Hemisphere temperatures reconstructed from low- and high-resolution proxy data. Nature 433, 613–617 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. et al. Last millennium northern hemisphere summer temperatures from tree rings: Part I: the long term context. Quat. Sci. Rev. 134, 1–18 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Grootes P. M., Stuiver M., White J. W. C., Johnsen S. & Jouzel J. Comparison of oxygen-isotope records from the GISP2 and GRIP greenland ice cores. Nature 366, 552–554 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Weissbach S. et al. Spatial and temporal oxygen isotope variability in northern Greenland - implications for a new climate record over the past millennium. Clim. Past 12, 171–188 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Cobb K. M., Charles C. D., Cheng H. & Edwards R. L. El Nino/Southern Oscillation and tropical Pacific climate during the last millennium. Nature 424, 271–276 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott F., Mattey D. P. & Hawkesworth C. Centennial-scale Holocene climate variability revealed by a high-resolution speleothem delta 18O record from SW Ireland. Science 294, 1328–1331 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffa-Sánchez P., Born A., Hall I. R., Thornalley D. J. R. & Barker S. Solar forcing of North Atlantic surface temperature and salinity over the past millennium. Nat. Geosci. 7, 275–278 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Sejrup H. P. et al. Response of Norwegian Sea temperature to solar forcing since 1000A.D. J. Geophys. Res. 115, doi:; DOI: 10.1029/2010jc006264 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor H. V. et al. Robust global ocean cooling trend for the pre-industrial Common Era. Nat. Geosci. 8, 671–67 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Tandon N. F. & Kushner P. J. Does external forcing interfere with the AMOC's influence on North Atlantic sea surface temperature? J. Clim. 28, 6309–6323 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Lund D. C., Lynch-Stieglitz J. & Curry W. B. Gulf Stream density structure and transport during the past millennium. Nature 444, 601–604 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanamaker A. D. Jr et al. Surface changes in the North Atlantic meridional overturning circulation during the last millennium. Nat. Commun. 3, 899 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfar J. et al. Coralline algal growth-increment widths archive North Atlantic climate variability. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 302, 71–80 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Masse G. et al. Abrupt climate changes for Iceland during the last millennium: evidence from high resolution sea ice reconstructions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 269, 565–569 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Denton G. H. & Broecker W. S. Wobbly ocean conveyor circulation during the Holocene? Quater. Sci. Rev. 27, 1939–1950 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Wanamaker A. D. Jr et al. Very long-lived mollusks confirm 17th century ad tephra-based radiocarbon reservoir ages for North Icelandic shelf waters. Radiocarbon 50, 399–412 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Vage K. et al. The Irminger Gyre: Circulation, convection, and interannual variability. Deep Sea Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Papers 58, 590–614 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Logemann K., Olafsson J., Snorrason A., Valdimarsson H. & Marteinsdottir G. The circulation of Icelandic waters - a modelling study. Ocean Sci. 9, 931–955 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Butler P. G., Wanamaker A. D., Scourse J. D., Richardson C. A. & Reynolds D. J. Variability of marine climate on the North Icelandic Shelf in a 1357-year proxy archive based on growth increments in the bivalve Arctica islandica. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 373, 141–151 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Mudelsee M. Break function regression. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 174, 49–63 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- IOC, SCOR and IAPSO. The International Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater–2010: Calculation and Use of Thermodynamic Properties. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Manuals and Guides No. 56, (UNESCO, 2010).

- Eiriksson J. et al. Coupling of palaeoceanographic shifts and changes in marine reservoir ages off North Iceland through the last millennium. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 302, 95–108 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ran L., Jiang H., Knudsen K. L. & Eiriksson J. Diatom-based reconstruction of palaeoceanographic changes on the North Icelandic shelf during the last millennium. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 302, 109–119 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Lean J., Beer J. & Bradley R. Reconstruction of solar irradiance since 1610 - implications for climate-change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 3195–3198 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Adams J. B., Mann M. E. & Ammann C. M. Proxy evidence for an El Nino-like response to volcanic forcing. Nature 426, 274–278 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swingedouw D. et al. Bidecadal North Atlantic ocean circulation variability controlled by timing of volcanic eruptions. Nat. Commun. 6, 12 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmstorf S. et al. Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 475–480 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Ebisuzaki W. A method to estimate the statistical significance of a correlation when the data are serially correlated. J. Clim. 10, 2147–2153 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Grossman E. & Ku T. Oxygen and carbon isotope fractionation in biogenic aragonite: temperature effects. Chem. Geol. 59, 59–74 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Dettman D. L., Reische A. K. & Clohmann K. Controls on the stable isotope composition of seasonal growth bands in aragonitic fresh-water bivalves (unionidae). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 1049–1057 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. M. et al. Temperature reconstructions for SW and N Iceland waters over the last 10calka based on δ18O records from planktic and benthic Foraminifera. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1723–1740 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Schöne B. R. et al. Climate records from a bivalved Methuselah (Arctica islandica, Mollusca; Iceland). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 228, 130–148 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Folonoff N. P. & Millard R. C. Jr Algorithms for computation of fundamental propertiers of seawater. UNESCO Tech. Papers Marine Sci. 44, (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Ryan W. B. F. et al. Global multi-resolution topography synthesis. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10, Q03014 (2009). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-12, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References

Data Availability Statement

Data are available through the NOAA climate data centre (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo/study/20448)