Abstract

The discovery of novel bromodomain inhibitors by fragment screening is complicated by the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), an acetyl-lysine mimetic, that can compromise the detection of low affinity fragments. We demonstrate surface plasmon resonance as a primary fragment screening approach for the discovery of novel bromodomain scaffolds, by describing a protocol to overcome the DMSO interference issue. We describe the discovery of several novel small molecules scaffolds that inhibit the bromodomains PCAF, BRD4, and CREBBP, representing canonical members of three out of the seven subfamilies of bromodomains. High-resolution crystal structures of the complexes of key fragments binding to BRD4(1), CREBBP, and PCAF were determined to provide binding mode data to aid the development of potent and selective inhibitors of PCAF, CREBBP, and BRD4.

Keywords: Bromodomains, surface plasmon resonance, fragment screening, BRD4, CREBBP, PCAF

The discovery of selective inhibitors of bromodomain proteins has accelerated investigations into the medical utility of blocking epigenetic readers.1,2 Currently, relatively selective and potent inhibitors have been identified for 17 of the 46 bromodomain proteins encoded by the human genome. Since the first bromodomain inhibitor was discovered by phenotypic screening,3 a variety of methods have been successfully employed to discover bromodomain inhibitors including phenotypic screening,4 analogue-based design,5 structure-based screening,6 focused-library screening,7 and fragment screening.8

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) has become a primary fragment screening method in recent years. SPR detects direct binding response in real time, allowing determination of binding kinetics, affinity, and stoichiometry. The advantages of label-free SPR assays include low sample quantities and low protein consumption. The high throughput of the current generation of instruments allows fast screening of fragment libraries (approximately 500 fragments per day), which enables fast turnaround from assay development to fragment binding hits that can then serve as starting points for further compound optimization. SPR has been used to characterize individual bromodomain inhibitors;8 however, surprisingly, SPR screening has not yet been routinely applied to the discovery of new bromodomain inhibitors. The challenge of SPR fragment screening of bromodomains lies in the fact that the most common solvent used for solubilization of fragment libraries, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), is itself an inhibitor of bromodomains, at the concentrations commonly used for compound solubilization.9

DMSO mimics the acetylated lysine motif that is the canonical ligand recognized by bromodomains.9,10 Bromodomains are, generally, sensitive to inhibition by DMSO.9 As DMSO is the most suitable solvent for fragment compound solubilization, it is not always possible to easily obtain libraries solubilized in alternative solvents such as methanol or ethanol, without going to the expense of resolubilizing the entire fragment library from solids. Inhibition by DMSO can therefore compromise detection of low affinity fragments binding to bromodomains. Here we describe a protocol for overcoming these issues while retaining use of DMSO solvent in assay buffer and fragment solutions to expand the repertoire of fragment screening methods applicable to the discovery of novel bromodomain compounds. We demonstrate the protocol by the discovery of novel small molecules scaffolds that inhibit the bromodomains of PCAF, BRD4, and CREBBP, representing canonical members of three out of the seven subfamilies of bromodomains.

The p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) forms part of the HAT complex that modifies chromatin.11 The PCAF bromodomain binds the acetyl-lysine promoting a feed-forward mechanism of acetylation to neighboring histones,12 thus reinforcing transcriptional activation of numerous genes, including insulin13 and p21.14 PCAF also acetylates a number of transcription factors including p53,15 c-Myc,16 and FOXO1.17 PCAF may also play an essential role in the replication cycle of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by its interaction with acetylated HIV Tat protein.18 Thus, pharmacological blockade of the PCAF/Tat interaction may disrupt the transcription of genes from integrated HIV provirus.

The cAMP response element binding protein-1 binding protein (CREBBP encoded by the gene CREBBP) possesses a single bromodomain (BRD)19 and a lysine acetyltransferase domain.20,21 CREBBP is ubiquitously expressed, and its pleiotropic binding and acetylation plays an important role on multiple transcription factors and coactivators.1 In G1 cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage, the CREBBP bromodomain binds to the acetylated tumor suppressor p53 at K382, thus playing an essential step in the p53 transcriptional activation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21.22 Pharmacological blockade of the CREBBP bromodomain has been shown to modulate p53 in response to DNA damage in cells.23 Thus, the modulation of the activation of p53, directly, and p21, indirectly, may have multiple clinical applications, including the protection healthy tissues during cancer therapy.

Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) is a member of the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) subfamily. BRD4, like other members of the BET subfamily, contains two related tandem bromodomains in the same polypeptide. BRD4 is the most extensively investigated bromodomain protein, facilitated by the availability of relatively selective and potent pharmacological inhibitors.1 Pharmacological blockage of BRD4 bromodomain has been shown to arrest proliferation and induce terminal squamous differentiation.5 Clinically, BRD4 inhibitors are being investigated as potential treatments for multiple myeloma, acute myelogenous leukemia, and a rare midline carcinoma that is genetically characterized by the fusion oncogene BRD4-NUT (nuclear protein in testis).

Here we describe the discovery of several new bromodomain chemotypes that can provide the basis for the development of bromodomains inhibitors of PCAF, BRD4, and CREBBP, using SPR fragment screening. The new fragments have been confirmed and characterized by SPR and the determination of high-resolution X-ray crystal structures of key fragment complexes with BRD4(1), CREBBP, and PCAF.

Proteins were cloned, expressed, and purified as previously described.24 Bromodomains CREBBP and BRD4 were captured via HIS-10 tag on NTA sensor chip in capture buffer consisting of 10 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 50 μM EDTA, 1% DMSO or 1% methanol, and 0.05% Tween 20 obtaining capture levels ∼5000 RU. Biacore T100, T200 and Biacore 4000 were used for all experiments. To increase stability of bromodomains on the surface, all experiments were conducted at 10 °C. Solvent correction was applied to all data during analysis.

To establish whether captured bromodomains were active on the sensor chip surface, the binding of compound 7179a9 was measured. Previously, it has been described bromodomains can bind DMSO with different affinities.9 To determine which concentration of DMSO can be used for screening of fragments, we measured the binding of 7179a to BRD4 and CREBBP in 1% methanol and 0.5%, 1%, and 3% DMSO. Sensorgrams for both bromodomains are shown in Figure 1. Compound 7179a was injected in duplicates at concentrations 1 to 250 μM in 3-fold concentration series. Affinities measured for 0% to 3% DMSO were in range between 37.7 to 310 μM for CREBBP and 17 to 102 μM for BRD4 and are summarized in Table 1. Approximately 10-fold difference in affinities was observed for the 7179a binding to both CREBBP and BRD4 when measured in the presence of 0% and 3% DMSO. To minimize effect of DMSO for further studies 1% DMSO was chosen for fragment screening.

Figure 1.

Binding sensorgrams for compound 7179a, fragment CPD-A to CREBBP and BRD4, and fragments CPD-D and CPD-E to PCAF in the presence of 0%, 0.5%, 1%, and 3% DMSO at concentrations 1 to 250 μM. Bottom graphs show equilibrium fits for each compound against each target. Colors correspond to DMSO concentrations (black = 0% DMSO, blue = 0.5% DMSO, red = 1% DMSO, green = 3% DMSO).

Table 1. Binding Affinities Measured by SPR for Compounds 7179a, A, B, and C to CREBB and BRD4, and D and E to PCAF.

| CREBB |

BRD4 |

PCAF |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | DMSO | KD (μM) | compd | DMSO | KD (μM) | compd | DMSO | KD (μM) |

| 7179a | 0% | 37.7 (± 0.6) | 7179a | 0% | 17.0 (± 0.1) | D | 0% | 73 (± 1) |

| 0.5% | 50.3 (± 0.9) | 0.5% | 20.4 (± 0.2) | 0.5% | 104 (± 2) | |||

| 1% | 103 (± 0.3) | 1% | 38.9 (± 0.5) | 1% | 166 (± 3) | |||

| 3% | 310 (± 20) | 3% | 102 (± 0.2) | 3% | 459 (± 4) | |||

| A | 0% | 1.53 (± 0.01) | A | 0% | 8.63 (± 0.05) | E | 0% | 250 (± 10) |

| 0.5% | 3.65 (± 0.03) | 0.5% | 17.4 (± 0.1) | 0.5% | 360 (± 20) | |||

| 1% | 7.08 (± 0.09) | 1% | 31.3 (± 0.3) | 1% | 660 (± 10) | |||

| 3% | 26.7 (± 0.4) | 3% | 97 (± 1) | 3% | 1080 (± 30) | |||

| B | 0% | 120.7 (± 0.4) | B | 0% | 84.8 (± 0.3) | |||

| C | 0% | 2100 (± 300) | C | 0% | 109.0 (± 0.4) | |||

All compounds were measured in the presence of 1% methanol (corresponding to 0% DMSO). Compounds 7179a, A, D, and E were measured in the presence of 0.5%, 1%, and 3% DMSO.

For fragment screening, all fragments were diluted into running buffer consisting of 50 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 50 μM EDTA, 1% DMSO, and 0.05% Tween 20 at concentrations 16.6, 50, and 150 μM and screened against both BRD4 and CREBBP in parallel using Biacore 4000. Association was measured for 30 s and dissociation for 30 s at flow rate 30 μL/min. Collected data were referenced for blank surface and blank injections of buffer and analyzed using Scrubber 2 software (BioLogic software). To evaluate screening data, single-point concentration response was read for each of the fragments before the end of injection.

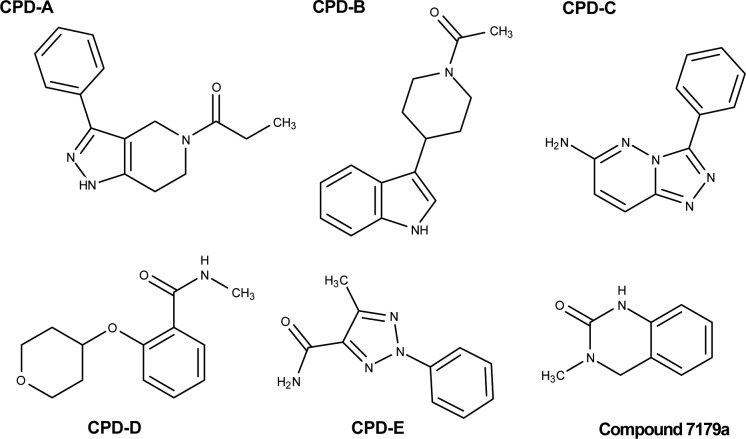

A total of 656 fragments were screened against BRD4 and CREBBP. Hits were selected based on concentration-dependent increased response at RU values corresponding to the control compound that was injected over all surfaces periodically during the screen. Seven potential fragment hits were selected and measured at 3-fold concentration series 1 to 250 μM in the running buffer containing 1% methanol. Three fragment hit compounds, CPD-A (Figure 1), CPD-B , and CPD-C (Supplementary Figure 1) that bound to both BRD4 and CREBBP bromodomains were confirmed by SPR dose–response series. Similar approach was used to screen PCAF bromodomain again resulting in finding two fragments, CPD-D and CPD-E (Figure 1). The structures of the five fragment hits CPD-A, CPD-B, CPD-C, CPD-D, and CPD-E are show in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of compound 7179a and the confirmed bromodomain fragment hits (CPD-[A–E]).

Three fragments CPD-A, CPD-B, and CPD-C were identified as binders to the bromodomains CREBBP and BRD4. Fragment CPD-A showed high affinity to both CREBBP and BRD4 with affinities KD = 1.5 μM and KD = 8.6 μM, respectively, in 0% DMSO. Fragment CPD-A was further characterized at various DMSO concentrations from 0 to 3% showing approximately 17-fold decrease and 11-fold decrease in affinity at 3% DMSO, for CREBBP and BRD4, respectively, compared to experiments using methanol as solvent. Fragment CPD-B showed similar affinities for both CREBBP (KD = 120 μM) and BRD4 (KD = 85 μM) (Table 1). Fragment CPD-C showed approximately a 20-fold selectivity to BRD4 (KD = 109 μM) compared to CREBBP (KD = 2100 μM). Sensorgrams for fragments CPD-B and CPD-C are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

In a separate experiment the same fragment library was screened against the PCAF bromodomain. As there were no known inhibitors of this bromodomain at the time of screening, the same screening conditions were used that were selected for screening of CREBBP and BRD4. Two fragments, CPD-D and CPD-E, were identified as hits against PCAF. The binding affinities for fragments CPD-D and CPD-E for PCAF were KD = 73 μM and KD = 250 μM, respectively. The affinities of CPD-D and CPD-E for PCAF were measured using methanol as a solvent. The affinities of CPD-D and CPD-E for PCAF decrease approximately 2-fold in the presence of 1% DMSO. Further increasing DMSO concentrations from 0% to 3% reduce the affinities of CPD-D and CPD-E for PCAF by 6-fold and 4-fold, respectively. The decrease in affinities, as measured by SPR, suggests that the compounds are competitive to DMSO binding site on PCAF and therefore consistent with competitive binding activity (Figure 1, Table 1). For all the fragments, increasing the concentrations higher than the concentrations described above resulted in limited solubility and nonspecific interactions.

The structures of three of the fragments hits, complexed with bromodomains, were determined by X-ray crystallography (Figure 3). The binding modes of fragment CPD-A complexed to the bromodomains BRD4(1) and CREBBP, respectively, was determined by X-ray crystallography (Figure 3). The X-ray crystal structure of CPD-C was determined bound to the PCAF bromodomain (Figure 3). CPD-E was also determined by X-ray crystallography in complex with PCAF (Figure 3). Crystals of BRD4(1) complexed with CPD-A and crystals CREBBP complexed with CPD-A of were grown by cocrystallizing each respective protein with the ligand. Crystals CPD-D or CPD-E were obtained by soaking apo PCAF crystals using the mother liquor supplemented with ligand. All crystallizations were carried out using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 4 °C. All crystals were cryo-protected using the well solution supplemented with additional ethylene glycol and were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected in-house on a Rigaku FRE rotating anode system equipped with a RAXIS-IV detector at 1.52 Å (BRD4(1)/CPD-A and CREBBP/CPD-A) or at Diamond, beamline I03 at a wavelength of 0.91997 Å (PCAF/CPD-D and PCAF/CPD-E). Initial phases were calculated by molecular replacement using the known models of BRD4(1), CREBBP, and PCAF (PDB IDs 2OSS, 3DWY, and 3GG3, respectively). Data collection and refinement statistics can be found in Supplemental Table 1. The models and structure factors have been deposited with PDB accession codes (see Supporting Information). Full experiments details of the crystallization and the X-ray crystallographic structure determination procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Complexes of human BRDs with small molecule fragments identified by SPR. Fragments were cocrystallized or soaked into the bromodomain acetyl-lysine cavity where they engaged the protein via hydrogen bonding to the conserved asparagine (N140 in BRD4(1), N1168 in CREBBP, and N803 in PCAF). Key residues and secondary structure elements are annotated in the complexes of (A) CPD-A with the first bromodomain of BRD4 (BRD4(1)); (B) CPD-A complexed with the bromodomain of CREBBP; (C) CPD-D in complex with PCAF; and (D) CPD-E in complex with PCAF. Compounds are shown in stick representation, and proteins are colored as indicated in the inset.

The four crystal structures determine that all the fragments bind in an acetyl-lysine mimetic mode, occupying the bromodomain cavity on top of the conserved water molecules. Proteins are engaged via a hydrogen bond from the carbonyl moiety of the ligands to the conserved asparagine (N140 in BRD4(1), N1168 in CREBBP, N803 in PACF). CPD-D was recently reported bound to the bromodomain of BAZ2B.25CPD-D engages PCAF and BAZ2B in a conserved mode (Supplementary Figure 2), CPD-D engaging the conserved asparagine (N803 in PCAF, N1944 in BAZ2B) while packing between the ZA-loop residues (E756, Y760, A757 in PCAF; L1897, Y1901, V1898 in BAZ2B) and a bulky residue from the tip of helix C (Y809 in PCAF; I1950 in BAZ2B).

Surface plasmon resonance assays for the screening of libraries of small molecules and fragments require careful assay preparation and development to ensure maintaining high activity of targets captured on sensor surface as well as controlling accurate sample preparation to avoid mismatch of high refractive index solvents used for compound solubilization. Bromodomain binding affinity to the widely used small molecule solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was studied previously.9 A majority of fragment screening campaigns use DMSO as standard solvent for preparing fragment libraries, however, this practice proves a challenge for bromodomains to screen for small molecule/fragment binders. A majority of fragment screens are usually run at DMSO concentrations ranging from 3% to 5% to increase solubility of compounds at higher concentrations. To establish whether bromodomains remain at least partially active in the presence of DMSO we measured the binding affinity of control compound 7179a to bromodomains BRD4 and CREBBP at DMSO concentrations ranging from 0 to 3%. We found that at 1% DMSO the affinity to the control compound decreased approximately 4-fold. We chose this DMSO concentration as a compromise between compound solubility and bromodomain activity to conduct a fragment screen.

We have shown that novel fragment hits, even in the presence of competing DMSO, can be discovered using the SPR assay protocol we have presented here. Ideally, bespoke fragment screening libraries could be designed including fragments soluble in alternative solvents as methanol that do not compromise binding affinity of analytes. However, the SPR protocol we have described here increases the range of approaches that can be applied to the discovery of bromodomain inhibitors, using conventional compound libraries.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- BRD4

bromodomain-containing protein 4

- PCAF

p300/CBP-associated factor

- CREBBD

cAMP response element binding protein-1 binding protein

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00154.

Methods and figures (PDF)

Accession Codes

PDB accession codes: 5LUU (BRD4(1)/CPD-A), 5TB6 (CREBBP(1)/CPD-A), 5LVQ (PCAF/CPD-D), 5LVR (PCAF/CPD-E).

Author Present Address

# Institute for Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University and Buchmann Institute for Molecular Life Sciences, Max-von-Laue-Strasse 9, D-60438 Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

This work is funded by the MSD Scottish Life Sciences Fund (to I.N.), in part by grants HL16037. P.F, S.P., A.C., and S.K. are supported by the SGC. The SGC is a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from AbbVie, Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Eshelman Institute for Innovation, Genome Canada, Innovative Medicines Initiative (EU/EFPIA) [ULTRA-DD grant no. 115766], Janssen, Merck & Co., Novartis Pharma AG, Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, Pfizer, São Paulo Research Foundation-FAPESP, Takeda, and Wellcome Trust (092809/Z/10/Z). P.F. and S.P. are supported by a Wellcome Career Development Fellowship (095751/Z/11/Z). A.H. was support in part by SULSA (HR07019).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang C.-Y.; Filippakopoulos P. Beating the Odds: BETs in Disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40 (8), 468–479. 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M.; Measures A. M.; Wilson B. G.; Cortopassi W. A.; Alexander R.; Höss M.; Hewings D. S.; Rooney T. P. C.; Paton R. S.; Conway S. J. Small Molecule Inhibitors of Bromodomain–Acetyl-Lysine Interactions. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10 (1), 22–39. 10.1021/cb500996u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo J.; Hikawa H.; Hamada M.; Ishibuchi S.; Fujie N.; Sugiyama N.; Tanaka M.; Kobayashi H.; Sugahara K.; Oshita K.; Iwata K.; Ooike S.; Murata M.; Sumichika H.; Chiba K.; Adachi K. A Phenotypic Drug Discovery Study on Thienodiazepine Derivatives as Inhibitors of T Cell Proliferation Induced by CD28 Co-Stimulation Leads to the Discovery of a First Bromodomain Inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26 (5), 1365–1370. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodeme E.; Jeffrey K. L.; Schaefer U.; Beinke S.; Dewell S.; Chung C.-W.; Chandwani R.; Marazzi I.; Wilson P.; Coste H.; White J.; Kirilovsky J.; Rice C. M.; Lora J. M.; Prinjha R. K.; Lee K.; Tarakhovsky A. Suppression of Inflammation by a Synthetic Histone Mimic. Nature 2010, 468 (7327), 1119–1123. 10.1038/nature09589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P.; Qi J.; Picaud S.; Shen Y.; Smith W. B.; Fedorov O.; Morse E. M.; Keates T.; Hickman T. T.; Felletar I.; Philpott M.; Munro S.; McKeown M. R.; Wang Y.; Christie A. L.; West N.; Cameron M. J.; Schwartz B.; Heightman T. D.; La Thangue N.; French C. A.; Wiest O.; Kung A. L.; Knapp S.; Bradner J. E. Selective Inhibition of BET Bromodomains. Nature 2010, 468 (7327), 1067–1073. 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M.; Unzue A.; Dong J.; Spiliotopoulos D.; Nevado C.; Caflisch A. Discovery of CREBBP Bromodomain Inhibitors by High-Throughput Docking and Hit Optimization Guided by Molecular Dynamics. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 59, 1340. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J.; Fedorov O.; Tallant C.; Monteiro O.; Meier J.; Gamble V.; Savitsky P.; Nunez-Alonso G. A.; Haendler B.; Rogers C.; Brennan P. E.; Müller S.; Knapp S. Discovery of a Chemical Tool Inhibitor Targeting the Bromodomains of TRIM24 and BRPF. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 59, 1642. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish P. V.; Filippakopoulos P.; Bish G.; Brennan P. E.; Bunnage M. E.; Cook A. S.; Federov O.; Gerstenberger B. S.; Jones H.; Knapp S.; Marsden B.; Nocka K.; Owen D. R.; Philpott M.; Picaud S.; Primiano M. J.; Ralph M. J.; Sciammetta N.; Trzupek J. D. Identification of a Chemical Probe for Bromo and Extra C-Terminal Bromodomain Inhibition Through Optimization of a Fragment-Derived Hit. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55 (22), 9831–9837. 10.1021/jm3010515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott M.; Yang J.; Tumber T.; Fedorov O.; Uttarkar S.; Filippakopoulos P.; Picaud S.; Keates T.; Felletar I.; Ciulli A.; Knapp S.; Heightman T. D. Bromodomain-Peptide Displacement Assays for Interactome Mapping and Inhibitor Discovery. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7 (10), 2899–10. 10.1039/c1mb05099k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lolli G.; Battistutta R. Different Orientations of Low-Molecular-Weight Fragments in the Binding Pocket of a BRD4 Bromodomain. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2013, 69 (10), 2161–2164. 10.1107/S090744491301994X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Wang L.; Zhao K.; Thompson P. R.; Hwang Y.; Marmorstein R.; Cole P. A. The Structural Basis of Protein Acetylation by the P300/CBP Transcriptional Coactivator. Nature 2008, 451 (7180), 846–850. 10.1038/nature06546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy Z.; Tora L. Distinct GCN5/PCAF-Containing Complexes Function as Co-Activators and Are Involved in Transcription Factor and Global Histone Acetylation. Oncogene 2007, 26 (37), 5341–5357. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampley M. L.; Özcan S. Regulation of Insulin Gene Transcription by Multiple Histone Acetyltransferases. DNA Cell Biol. 2012, 31 (1), 8–14. 10.1089/dna.2011.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love I. M.; Sekaric P.; Shi D.; Grossman S. R.; Androphy E. J. The Histone Acetyltransferase PCAF Regulates P21 Transcription Through Stress-Induced Acetylation of Histone H3. Cell Cycle 2012, 11 (13), 2458–2466. 10.4161/cc.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Y.; Lee K. S.; Seol J. E.; Yu K.; Chakravarti D.; Seo S. B. Inhibition of P53 Acetylation by INHAT Subunit SET/TAF-I Represses P53 Activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40 (1), 75–87. 10.1093/nar/gkr614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel J. H.; Du Y.; Ard P. G.; Phillips C.; Carella B.; Chen C.-J.; Rakowski C.; Chatterjee C.; Lieberman P. M.; Lane W. S.; Blobel G. A.; McMahon S. B. The C-MYC Oncoprotein Is a Substrate of the Acetyltransferases hGCN5/PCAF and TIP60. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24 (24), 10826–10834. 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10826-10834.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimochi K.; Daitoku H.; Fukamizu A. PCAF Represses Transactivation Function of FOXO1 in an Acetyltransferase-Independent Manner. J. Recept. Signal Transduction Res. 2010, 30 (1), 43–49. 10.3109/10799890903517947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba S.; He Y.; Zeng L.; Farooq A.; Carlson J. E.; Ott M.; Verdin E.; Zhou M.-M. Structural Basis of Lysine-Acetylated HIV-1 Tat Recognition by PCAF Bromodomain. Mol. Cell 2002, 9 (3), 575–586. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen L. J.; Gelly J. C.; Hipskind R. A. Induction-Independent Recruitment of CREB-Binding Protein to the C-Fos Serum Response Element Through Interactions Between the Bromodomain and Elk-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276 (7), 5213–5221. 10.1074/jbc.M007824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogryzko V. V.; Schiltz R. L.; Russanova V.; Howard B. H.; Nakatani Y. The Transcriptional Coactivators P300 and CBP Are Histone Acetyltransferases. Cell 1996, 87 (5), 953–959. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)82001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvecchio M.; Gaucher J.; Aguilar-Gurrieri C.; Ortega E.; Panne D. Structure of the P300 Catalytic Core and Implications for Chromatin Targeting and HAT Regulation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20 (9), 1040–1046. 10.1038/nsmb.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba S.; He Y.; Zeng L.; Yan S.; Plotnikova O.; Sachchidanand; Sanchez R.; Zeleznik-Le N. J.; Ronai Z.; Zhou M.-M. Structural Mechanism of the Bromodomain of the Coactivator CBP in P53 Transcriptional Activation. Mol. Cell 2004, 13 (2), 251–263. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay D. A.; Fedorov O.; Martin S.; Singleton D. C.; Tallant C.; Wells C.; Picaud S.; Philpott M.; Monteiro O. P.; Rogers C. M.; Conway S. J.; Rooney T. P. C.; Tumber A.; Yapp C.; Filippakopoulos P.; Bunnage M. E.; Müller S.; Knapp S.; Schofield C. J.; Brennan P. E. Discovery and Optimization of Small-Molecule Ligands for the CBP/P300 Bromodomains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (26), 9308–9319. 10.1021/ja412434f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P.; Picaud S.; Mangos M.; Keates T.; Lambert J.-P.; Barsyte-Lovejoy D.; Felletar I.; Volkmer R.; Müller S.; Pawson T.; Gingras A.-C.; Arrowsmith C. H.; Knapp S. Histone Recognition and Large-Scale Structural Analysis of the Human Bromodomain Family. Cell 2012, 149 (1), 214–231. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson F. M.; Fedorov O.; Chaikuad A.; Philpott M.; Muniz J. R. C.; Felletar I.; Delft; von F.; Heightman T.; Knapp S.; Abell C.; Ciulli A. Targeting Low-Druggability Bromodomains: Fragment Based Screening and Inhibitor Design Against the BAZ2B Bromodomain. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56 (24), 10183–10187. 10.1021/jm401582c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.