Abstract

PAR2 antagonists have potential for treating inflammatory, respiratory, gastrointestinal, neurological, and metabolic disorders, but few antagonists are known. Derivatives of GB88 (3) suggest that all four of its components bind at distinct PAR2 sites with the isoxazole, cyclohexylalanine, and isoleucine determining affinity and selectivity, while the C-terminal substituent determines agonist/antagonist function. Here we report structurally similar PAR2 ligands with opposing functions (agonist vs antagonist) upon binding to PAR2. A biased ligand AY117 (65) was found to antagonize calcium release induced by PAR2 agonists trypsin and hexapeptide 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (IC50 2.2 and 0.7 μM, HT29 cells), but it was a selective PAR2 agonist in inhibiting cAMP stimulation and activating ERK1/2 phosphorylation. It showed anti-inflammatory properties both in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2), antagonist, agonist, structure−activity relationship (SAR), inflammation

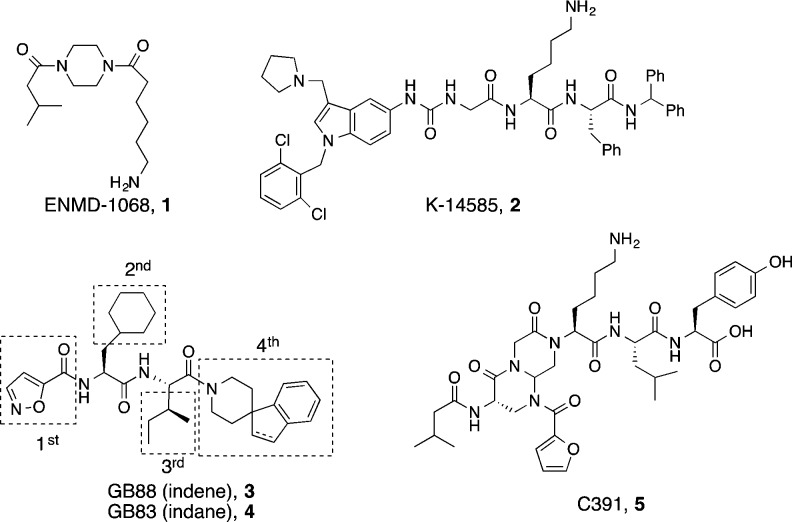

Protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2) is a G protein coupled receptor activated by endogenous proteases.1,2 PAR2 is activated in various inflammatory, respiratory, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, neurological, and metabolic diseases, as well as skin conditions and pain.1,3−10 Inhibiting the functions of PAR2 could have potential therapeutic applications in treating these diseases. Of the few PAR2 antagonists known, ENMD1068 (1) is a weak antagonist at millimolar concentrations.11 K-14585 (2) is a weak antagonist at low micromolar concentrations of peptide agonists according to a NF-κB-luciferase reporter gene assay,12 but not of endogenous proteases like trypsin.13 C391 (5, Figure 1) inhibited PAR2 mediated Ca2+ and MAPK signaling pathways at micromolar concentrations.14 There are some other small molecule antagonists reported in patents (not shown).15 Our group previously identified the first micromolar–nanomolar antagonists GB88 (3) and GB83 (4)16,17 that inhibited PAR2 activation of intracellular calcium (iCa2+) release induced by all known PAR2 agonists, including proteases (e.g., trypsin) or synthetic peptide agonists (e.g., SLIGRL-NH2, 2fLIGRLO-NH2) or nonpeptide agonists (e.g., GB110) in multiple human cell lines.17 Their potential therapeutic applications were demonstrated for 3in vivo in both acute and chronic inflammatory rat models.17−20

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of PAR2 antagonists (1–5) and modular optimization (boxed) in this study.

This study reports structure–activity relationships (SARs) in which each component (isoxazole, cyclohexylalanine, isoleucine, spiro[indene-1,4′-piperidine]) of 3 (Figure 1) is altered to gain more understanding of their contributions to PAR2 modulation (Figure 2). We propose that each motif (isoxazole, Cha, Ile, C-terminus) binds to different regions of PAR2 to modulate downstream signaling pathways, leading to discovery of selective pathway-controlled biased ligands.

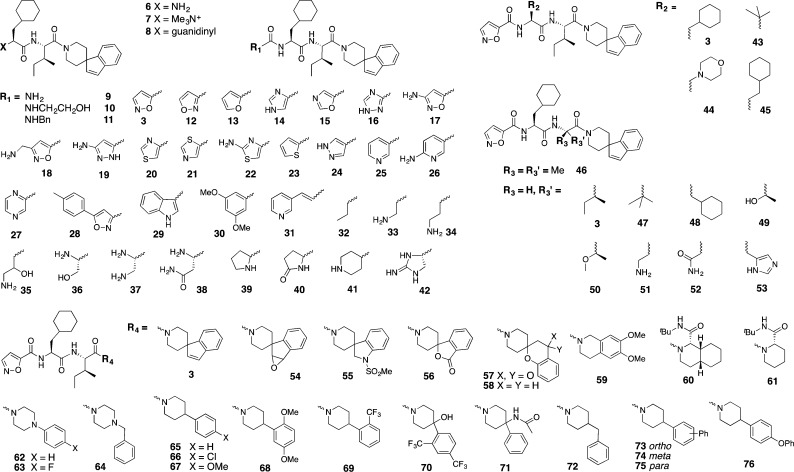

Figure 2.

Modular changes to each component of 3.

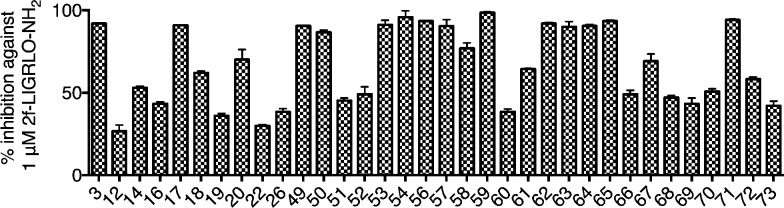

Each motif was replaced with different moieties, and the PAR2 antagonist/agonist activities were assessed initially by intracellular calcium (iCa2+) release in human colorectal carcinoma (HT29) cells. All ligands were first screened for antagonist activity at two concentrations (10 and 100 μM, Figure 3), and those showing significant inhibition (>30% at 10 μM) were further screened for agonist activity (at 10 μM) to establish that the observed inhibition was not caused by agonist-induced receptor desensitization.16 Promising antagonists were further assessed over full-concentration ranges to determine half-maximum inhibition (IC50) of iCa2+ release and profiled in other functional assays such as cAMP stimulation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Properties of PAR2 antagonists were then briefly examined in vitro and in vivo in models of inflammation.

Figure 3.

Initial screening of representative compounds at 10 μM (>30% inhibition) for reducing calcium efflux in HT29 cells elicited by 1 μM 2-f-LIGRLO-NH2. Data are means ± SEM (n ≥ 2). Compounds 12, 19, 49, 50, 52–57, 59, 62–64, and 71 were agonists, which falsely read as antagonists due to agonist-induced receptor desensitization16 (Supporting Information Figure S1).

The role of backbone amides of 3 was first investigated through N-methylation. Neither of the two mono N-methylated derivatives of 3 showed any activity. This indicated the importance of both backbone amides, possibly due to maintaining a preferred trans-amide conformation for presenting side-chains or for hydrogen bonding to the receptor.

SAR around the isoxazole motif of 3 was investigated using cyclic or acyclic moieties differing in hydrophobicity, size, saturation, and polarity (Figure 2). Only 5-membered aromatic heterocycles were generally tolerated (14, 17–18, and 20 with 53, 91, 62, and 70% inhibition at 10 μM). Other ligands with positive charged amine or guanidine groups (6–8), urea (9), hydroxyethyl or benzyl ureas (10–11), bulky aromatics (28–31), alkyl and aminoalkyl groups (32–34), serine mimics (35–38), or nonaromatic heterocycles (39–42) were less potent (Figure 3).

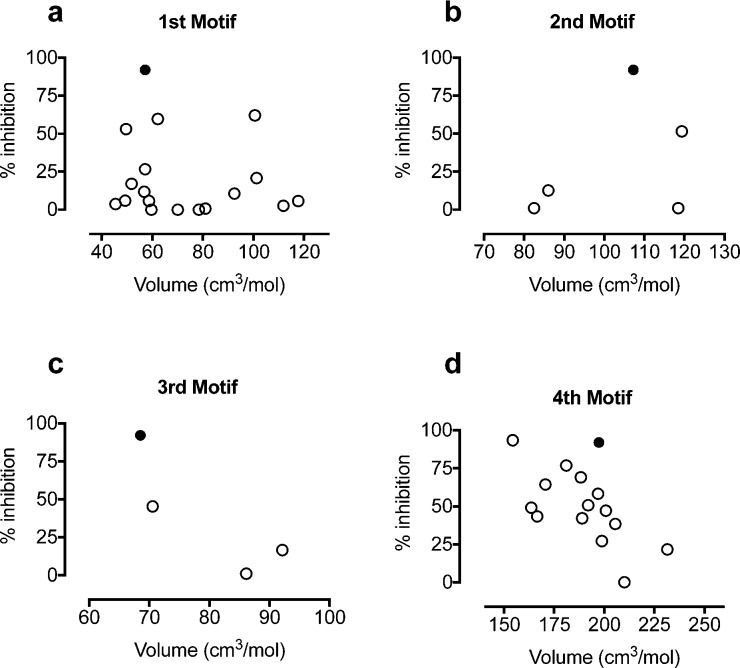

Switching the relative position of the oxygen/nitrogen from 5-isoxazole (3) to 3-isoxazole (12) or 5-oxazole (15) was detrimental for antagonist activity. Isomer 12 showed weak inhibition (27%), likely due to weak agonist activity (21% activation, Supporting Information, Figure S1). In contrast to the observation in peptide agonists, where replacement of the serine of SLIGRL-NH2 with 2-furan produced the most active PAR2 agonist 2f-LIGRLO-NH2,21 replacement of 5-isoxazole in 3 with either 2-furan (13) or serine (36) abolished activity. The results suggest that 3 could share the same or overlapping binding site as peptide agonists (e.g., 2f-LIGRLO-NH2) but bind differently at the site accommodating the first residue (5-isoxazole vs 2-furan or serine). In particular, the H-bond acceptor property at meta and/or ortho positions on 5-isoxazole could play a role in binding and function. Therefore, a series of heteroaromatics with such properties were investigated. Imidazole (14) and triazole (16) retained antagonist activity with reduced potency (53% and 43%, respectively). Position 3 of the 5-isoxazole ring is known to be the primary metabolic site in isoxazole drugs.22,23 Addition of an amino group at this position might improve metabolic stability and form an extra H-bonding interaction with PAR2. However, the resulting 3-amino-5-isoxazole (17) showed comparable antagonist potency to 3 (91% and 92%, respectively, or IC50 1–2 μM, Table 1). Introducing flexibility by extending the distance between amino group and isoxazole using a methylene spacer (18) led to reduced antagonist potency (62%; IC50 8.9 μM). Replacing the ring oxygen of 3-amino-5-isoxazole (17) with a H-bond donor (NH) gave the 3-amino-5-pyrazole (19), which switched to a weak agonist (26% activation, Supporting Information Figure S1). Substituting the isoxazole with 2-amino-4-thiazole (22) reduced antagonist activity (30%) but, surprisingly, the 4-thiazole analogue (20, 70%) showed some antagonist activity while the 5-thiazole compound (21) was inactive at 10 μM. The imidazole 14, pyrazole 19, and triazole 16 can exist in tautomeric forms, causing the meta nitrogen to act as either H-bond donor or acceptor. Removal of H-bond donor/acceptor at the meta position abolished activity, demonstrated by the furan (13) and thiophene (23) analogues, suggesting that a H-bond acceptor at the meta position is important for antagonism and potency. Pyrazole (24), containing a H-bond acceptor at the meta but not ortho position, had >10-fold reduced potency. Replacing five- with six-membered nitrogen-containing heteroaromatics, while maintaining the same type of H-bond acceptor property at the meta-position (e.g., pyridine 25, 6-aminopyridine 26, and pyridazine 27), significantly reduced antagonist potency. This is consistent with enhanced H-bond acceptance of 5- vs 6-membered nitrogen containing heterocycles,24 the former being more electron-rich. In particular, the vicinal oxygen in 5-isoxazole could enhance H-bond acceptor power of the meta nitrogen. Unlike other binding motifs, the size of the substituent at this position does not directly affect activity (Figure 4a). A minimum of two heteroatoms (nitrogen or oxygen, as in 3) acting as H-bond acceptors is required in five-membered heteroaromatics for antagonist potency. PAR2 antagonists were found with alternative heteroaromatics, such as imidazole (14) or 3-substituted 5-isoxazoles analogues (17 and 18, IC50 1–9 μM, Table 1), which may have better metabolic stability and solubility, but potency would need to be obtained by changes elsewhere in the structures.

Table 1. Representative PAR2 Antagonists Inhibit iCa2+ Efflux in HT29 Cells Induced by 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (1 μM)a.

| compd | pIC50 | IC50 (μM) | compd | pIC50 | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 1.7 | 58 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 1.9 |

| 14 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 3.1 | 61 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 8.6 |

| 17 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 1.2 | 65 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 0.7 |

| 18 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 8.9 |

Data are means ± SEM (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Relationship between volume of side chain and % inhibition at 10 μM iCa2+ induced by 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (1 μM). Solid dot (antagonist 3), open dots (PAR2 ligands from Figure 2).

For PAR2 agonist peptides, it has been reported that changes at the second residue in SLIGRL-NH2 from leucine to phenylalanine led to loss of selectivity for PAR2 over PAR1.25 For this reason aromatic rings were excluded at this position. The size of the complementary binding pocket was probed using hydrophobic alkyl groups of slightly varying size, such as tert-butyl glycine (tBuG, 43) homocyclohexylalanine (hCha, 45), and morpholine (44) (Figure 2), but no replacement was successful. Together with knowledge from PAR2 peptide agonists,26 Cha was the best substituent at this site (3, solid dot, Figure 4b), most likely due to optimal hydrophobic space-filling and van der Waals interactions with PAR2.

PAR2 peptide agonist studies reported that position 3 was intolerant of substitution of amino acids smaller than Ile and bulkier than Cha.25 Given this binding pocket is relatively small in our PAR2 homology model,26 only groups of similar size to Ile and Cha were selected. Alkyl groups such as gem-dimethyl (46), t-butyl glycine (47), and Cha (48) (Figure 2) showed reduced potency (10–16% inhibition). Selected polar groups with similar size to Ile were incorporated, such as threonine (49), O-methylated threonine (50, a CH2 to O isostere of Ile), α,γ-diaminobutyric acid (51), asparagine (52), and histidine (53), to investigate polar or H-bond interactions with the receptor. However, all induced PAR2 activation (53–81%, except 11% for 51, Supporting Information Figure S1). The data support a hydrophobic pocket for antagonist potency, with Ile (3, solid dot, Figure 4c) as optimal substituent. Polar groups at this position switched antagonists to agonists.

It has been suggested that PAR2 may have a hydrophobic pocket that can accommodate the fifth and sixth residue of the tethered ligand.25−27 Therefore, the spiro[indene-1,4′-piperidine] of 3 was replaced with different aliphatic or aromatic hydrophobic groups. Spiro or bicyclic moieties commonly found in GPCR ligands were thus incorporated.28 Spiro compounds with H-bond acceptors (54, 56, 57) became potent agonists (EC50 0.7–1.8 μM, or 62–70% activation, Supporting Information Figure S1). Removal of the carbonyl oxygen (57 to 58) completely restored antagonist activity with similar potency as 3 (77% inhibition or IC50 1.9 μM, Table 1). A similar rationale was clear for another antagonist/agonist pair 3 and 54, while the latter containing an epoxide vs double bond (in 3) at this location was an agonist (65% activation). Bicyclic tetrahydroisoquinoline derivative 59 showed an agonist response (65% activation), possibly because one of the two methoxy groups was presented in the same position triggering H-bond acceptor-induced receptor activation. The fully saturated bicycle 60 (cis-decahydroisoquinoline) had moderate antagonist activity (38% inhibition), and removal of one cyclohexane ring (61, also with a tert-butyl amide group at position-2 of piperidine like in 60) improved antagonist potency (64% inhibition; IC50 8.6 μM). The results suggest space available around position-2 of the piperidine ring of 61.

Substituted piperazines and piperidines are other classes of common fragments found in various GPCR ligands.28 Piperazines are readily derivatized at the ring nitrogen at position 4. However, the extra ring nitrogen can change electronic properties and make a polar interaction with receptor to trigger agonist activity. The piperazine candidates (62–64) were indeed all agonists (30–50% activation, Supporting Information Figure S1). Therefore, attention was focused on piperidines. Promisingly, an analogue of 3 created by removing the 5-membered spiro ring, 4-phenylpiperidine (65), showed improved antagonist activity (93% inhibition or IC50 0.7 μM).

Phenylpiperidine 65 was modified by incorporating electron-donating (MeO, 67 and 68) or electron-withdrawing (chloro, 66; trifluoromethyl, 69 and 70) groups, but all showed reduced antagonist activity (43–69% inhibition). Introducing an acetamido group (71) switched the role to agonist (81% activation), supporting earlier observations that a H-bond acceptor at this location led to receptor activation. To probe the size of this C-terminal binding pocket, inserting a methylene spacer between piperidine and phenyl (72) or incorporating a phenyl (73–75) or phenoxy (76) group led to reduced antagonism or inactivation. Our findings indicated that space around the phenyl ring of phenylpiperidine is limited and an unsubstituted phenyl is optimal. Figure 4d suggests that substituents larger than spiroindenepiperidine (3, solid dot) were not tolerated, while smaller groups did not significantly reduce antagonist potency. Importantly, the C-terminal motif also determined agonist/antagonist function primarily by a H-bond accepting property, which was missing in all analogous antagonists but present in agonists, such as the pairs 3 vs 54 (double bond vs epoxide), 58 vs 57 (methylene vs keto carbonyl), and 65 vs 62/71 (CHPh vs NPh/acetamido-CPh).

Selected antagonists identified in the iCa2+ assay were assessed over a full concentration range to determine IC50, which showed comparable potency to 3 (Table 1, Supporting Information Figure S2). The most potent antagonist 65 inhibited iCa2+ release in human colorectal carcinoma (HT29) cells induced by two types of PAR2 agonists, e.g., peptide 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (IC50 0.7 μM) and endogenous protease trypsin (IC50 2.2 μM), and was slightly more potent than 3 (IC50 1.1 and 3.6 μM, respectively). Further, 65 was selective for PAR2 over PAR1. Since HT29 cells do not express PAR1 in our hands (Supporting Information Figure S3), we examined 65 for PAR2 vs PAR1 selectivity in human prostate cancer (PC3) cells, which express both PAR2 and PAR1 (Supporting Information Figure S3). Compound 65 inhibited iCa2+ release induced in PC3 cells by either 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (IC50 4.5 μM) or trypsin (IC50 6.5 μM), but had no effect in inhibiting iCa2+ release stimulated by two PAR1 selective agonists, e.g., protease α-thrombin and peptide TFLLR-NH2 (Figure 5a).

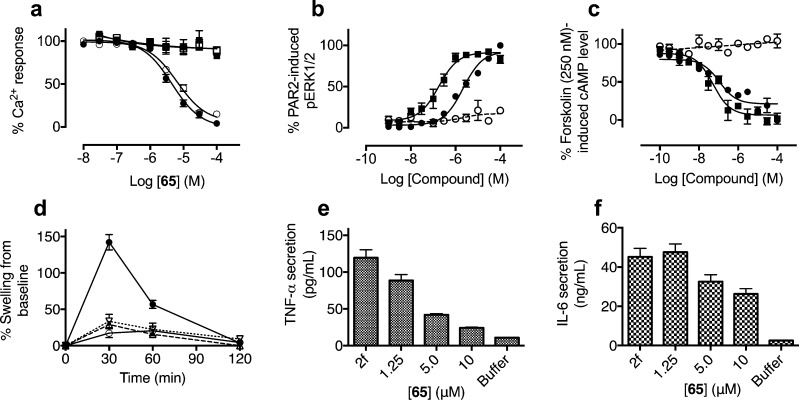

Figure 5.

Profiling signaling and anti-inflammatory properties of compound 65 in PAR2 functional assays. (a) Compound 65 selectively inhibits iCa2+ release induced in PC3 cells by two different PAR2 agonists at their EC80 concentrations: endogenous trypsin (○, pIC50 5.2 ± 0.1) and peptide 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (●, pIC50 5.3 ± 0.1). However, 65 had no effect against two PAR1 agonists: endogenous thrombin (□) at 100 nM and peptide TFLLR-NH2 (■) at 50 μM in PC3 cells. PAR2-selective agonist activities of 65 (● and ○) showing concentration-dependent (b) phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and (c) down-regulation of cAMP versus 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (■) in CHO-PAR2 (solid lines) versus CHO transfected with vector only (dotted lines, corresponding curves for 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 are flat lines reported previously).29 pEC50 for 65 in ERK1/2 is 5.7 ± 0.1 (EC50 2.2 ± 0.6 μM) and pIC50 in cAMP is 7.0 ± 0.3 (IC50 109 ± 50 nM), in comparison to 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 at pEC50 in ERK1/2 6.8 ± 0.2 (0.18 ± 0.07 μM) and pIC50 in cAMP 7.3 ± 0.2 (IC50 = 52 ± 22 nM). (d) Selected PAR2 antagonists are orally active and attenuate PAR2-mediated paw edema in rats at 10 mg/kg p.o. 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 alone (●, 350 μg/paw in 100 μL saline) and also pretreated (2 h) with GB88 (○) or 17 (▽, dotted line) or 65 (△, dashed line). (e,f) Representative PAR2 antagonist 65 dose-dependently inhibited 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (1 μM, abbreviated as 2f in figures) induced stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (e) TNF-α and (f) IL-6 in primary human kidney tubule epithelial cells (HTEC). Each data point represents mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3).

Compound 65 was a competitive and surmountable antagonist against 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 as determined by Schild plot analysis (Supporting Information Figure S4). Similar to 2f-LIGRLO-NH2, 65 was a PAR2-selective agonist in activating ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 5b) and inhibiting cAMP stimulation (Figure 5c). PAR2 selectivity was further supported by agonist activity for 65 in both assays in PAR2- but not vector-transfected CHO cells. Most importantly, the concentration of 65 required to inhibit iCa2+ mobilization induced by 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 in HT29 cells was similar to that needed to activate the ERK1/2 and cAMP responses (0.1–2.2 μM).

Three antagonists (3, 17, 65) were examined for stability in rat plasma and rat liver homogenates over a period of 3 h (Supporting Information, Figure S5) and compared with peptide SLIGRL-NH2. In rat plasma, the antagonists were stable over 3 h (>75% intact), whereas the hexapeptide SLIGRL-NH2 degraded quickly (t1/2 ≈ 20 min). In rat liver homogenates, the elimination half time of these compounds was less than 60 min in the rank order 3 (t1/2 ≈ 60 min) > 65 (∼30 min) > SLIGRL-NH2 and 3-aminoisoxazole 17 (∼15 min). Oral delivery of the antagonists to rats (10 mg/kg in olive oil) indicated that analogue 17 gave an almost identical pharmacokinetic profile to 3(19) (data not shown), whereas phenylpiperidine (65) showed a lower plasma concentration over 6 h (AUC6h 1964 ng·h/mL compared to 3420 ng·h/mL for 3, Supporting Information Figure S5 and Table S1). Similar to 3, compound 65 reached maximum plasma concentration 2–3 h after an oral dose, with maximum plasma concentration reaching ∼2 × IC50 value in vitro.

Antagonists 17 and 65 were studied here in an established acute rat paw inflammation model.11,17 When administered orally at 10 mg/kg (in olive oil) in the rat edema model, both 17 and 65 significantly reduced joint swelling induced by PAR2 agonist 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 (350 μg/paw in 100 μL saline. p < 0.05 repeated measures ANOVA, bonferroni planned comparison), with efficacy comparable to 3 (Figure 5d). Estimated oral bioavailability (AUC6h) of 65 was less than for 3, but comparable in vivo efficacy supported its greater PAR2 antagonist potency determined in vitro. Activation of PAR2 is known to induce release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α).30−32 Given the high abundance of PAR2 in kidney and its pro-inflammatory roles,33 we investigated PAR2 agonists and antagonists in primary human kidney tubule epithelial cells (HTEC). Stimulating HTEC with PAR2 agonist (2f-LIGRLO-NH2) increased TNF-α and IL-6 secretion. Pretreatment with PAR2 antagonist 65 dose-dependently inhibited 2f-LIGRLO-NH2-stimulated cytokine secretion (Figure 5e,f), correlating well with anti-inflammatory activity in rat paws.

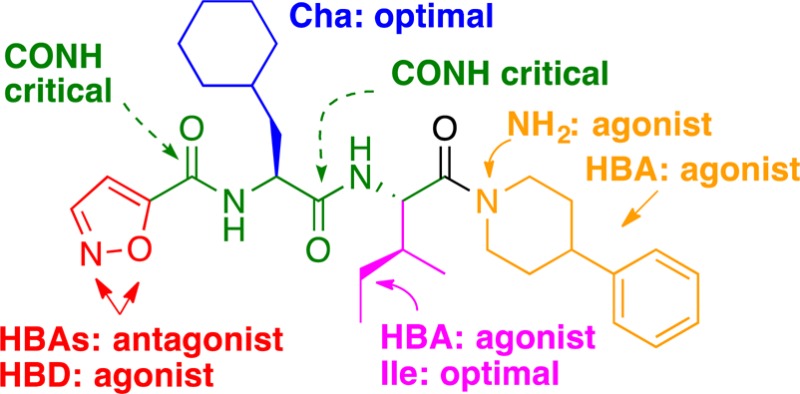

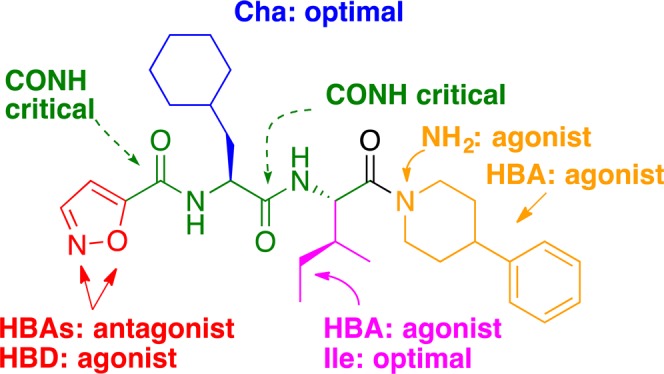

In summary, this SAR study (Figure 6) around our previous antagonist 3 (GB88) led to discovery of several low micro- to submicromolar PAR2 antagonists in an iCa2+ release assay (HT29, PC3, CHO-PAR2 cells). An agonism/antagonism switch was found and harnessed for antagonist design. Optimal sizes were identified for component motifs replacing isoxazole, isoleucine, cyclohexylalanine, and C-terminal moieties. Influences of each component on agonism vs antagonism were attributed to variable fitting of binding pockets in transmembrane regions of PAR2, which might help studies of membrane-dependent (possibly pathway-dependent) signaling mediated by PAR2. Removing a H-bond acceptor at three of the four motifs was critical to maintain antagonist activity. A representative antagonist (65, designated AY117) was slightly better than 3 as a PAR2 antagonist in inhibiting PAR2 activated iCa2+ release induced by native (trypsin) or synthetic peptide (2f-LIGRLO-NH2) agonists. Compound 65 was a competitive and insurmountable antagonist of agonist 2f-LIGRLO-NH2 in iCa2+ regulation. However, like 2f-LIGRLO-NH2, it is a PAR2-selective agonist in inhibiting cAMP stimulation and activating ERK1/2 phosphorylation at similar concentrations (0.1–2.2 μM). The new ligands are stable in rat plasma, orally active, and show comparable in vivo anti-inflammatory activity (3) in a rat paw edema model, consistent with their ability to attenuate PAR2 agonist-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted in vitro. These findings connect PAR2 function in modulating acute inflammation to antagonizing the iCa2+ pathway and demonstrate the potential for pathway-selective modulators in the context of GPCR drug design. These new PAR2 ligands offer new clues for investigating PAR2 functions in signaling pathways and in inflammatory diseases.

Figure 6.

Effects of components of 65 on agonist vs antagonist activity measured by iCa2+ release against PAR2 agonist 2f-LIGRLO-NH2. HBA/HBD: hydrogen bond acceptor/donor.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) for a Senior Principal Research Fellowship to D.F. (1027369) and NHMRC (1047759, 1084083, 1083131) and the Australian Research Council (CE140100011) for grant support.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- 2f

2-furoyl

- Cha

L-cyclohexylalanine

- CHO

Chinese Hamster Ovary

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases

- H-bond

hydrogen bond

- hCha

L-homocyclohexylalanine

- HT29

human colon adenocarcinoma cells

- HTEC

human tubule epithelial cells

- iCa2+

intracellular calcium

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PAR1

protease activated receptor 1

- PAR2

protease activated receptor 2

- PC3

human prostate cancer cells

- Ph

phenyl

- tBuG

tert-butyl glycine

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00306.

Experimental procedures, compound characterization (1H NMR, HRMS, HPLC), and assay results of all final compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

‡ These authors contributed equally to this work. All authors contributed to the data and writing of this manuscript.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): University of Queensland owns a patent (AU2010903378) that includes these compounds.

Supplementary Material

References

- Adams M. N.; Ramachandran R.; Yau M. K.; Suen J. Y.; Fairlie D. P.; Hollenberg M. D.; Hooper J. D. Structure, function and pathophysiology of protease activated receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 130, 248–282. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R.; Noorbakhsh F.; Defea K.; Hollenberg M. D. Targeting proteinase-activated receptors: therapeutic potential and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 69–86. 10.1038/nrd3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks T. M.; Moffatt J. D. Protease-activated receptors: sentries for inflammation?. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000, 21, 103–108. 10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell W. R.; Lockhart J. C.; Kelso E. B.; Dunning L.; Plevin R.; Meek S. E.; Smith A. J.; Hunter G. D.; McLean J. S.; McGarry F.; Ramage R.; Jiang L.; Kanke T.; Kawagoe J. Essential role for proteinase-activated receptor-2 in arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 111, 35–41. 10.1172/JCI16913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmoul D.; Gratio V.; Devaud H.; Laburthe M. Protease-activated receptor 2 in colon cancer: trypsin-induced MAPK phosphorylation and cell proliferation are mediated by epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 20927–20934. 10.1074/jbc.M401430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J. J. Proteinase-activated Receptor 2 (PAR2): a challenging new target for treatment of vascular diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 2769–2778. 10.2174/1381612043383656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanke T.; Takizawa T.; Kabeya M.; Kawabata A. Physiology and pathophysiology of proteinase-activated receptors (PARs): PAR-2 as a potential therapeutic target. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2005, 97, 38–42. 10.1254/jphs.FMJ04005X7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishibori M.; Mori S.; Takahashi H. K. Physiology and pathophysiology of proteinase-activated receptors (PARs): PAR-2-mediated proliferation of colon cancer cell. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2005, 97, 25–30. 10.1254/jphs.FMJ04005X5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi F. Development of agonists/antagonists for protease-activated receptors (PARs) and the possible therapeutic application to gastrointestinal diseases. Yakugaku Zasshi 2005, 125, 491–498. 10.1248/yakushi.125.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu T.; Savage E.; Zhao P.; Edgington-Mitchell L.; Barlow N.; Bron R.; Poole D. P.; McLean P.; Lohman R. J.; Fairlie D. P.; Bunnett N. W. Antagonism of the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of canonical and biased agonists of protease activated receptor-2. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 2752–2765. 10.1111/bph.13554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso E. B.; Lockhart J. C.; Hembrough T.; Dunning L.; Plevin R.; Hollenberg M. D.; Sommerhoff C. P.; McLean J. S.; Ferrell W. R. Therapeutic promise of proteinase-activated receptor-2 antagonism in joint inflammation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 316, 1017–1024. 10.1124/jpet.105.093807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanke T.; Kabeya M.; Kubo S.; Kondo S.; Yasuoka K.; Tagashira J.; Ishiwata H.; Saka M.; Furuyama T.; Nishiyama T.; Doi T.; Hattori Y.; Kawabata A.; Cunningham M. R.; Plevin R. Novel antagonists for proteinase-activated receptor 2: inhibition of cellular and vascular responses in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 361–371. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh F. G.; Ng P. Y.; Nilsson M.; Kanke T.; Plevin R. Dual effect of the novel peptide antagonist K-14585 on proteinase-activated receptor-2-mediated signalling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 1695–1704. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitano S.; Hoffman J.; Flynn A. N.; Asiedu M. N.; Tillu D. V.; Zhang Z.; Sherwood C. L.; Rivas C. M.; DeFea K. A.; Vagner J.; Price T. J. The novel PAR2 ligand C391 blocks multiple PAR2 signalling pathways in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 4535–4545. 10.1111/bph.13238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau M. K.; Liu L.; Fairlie D. P. Towards drugs for protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7477–7479. 10.1021/jm400638v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry G. D.; Suen J. Y.; Le G. T.; Cotterell A.; Reid R. C.; Fairlie D. P. Novel agonists and antagonists for human protease activated receptor 2. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 7428–7440. 10.1021/jm100984y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen J. Y.; Barry G. D.; Lohman R. J.; Halili M. A.; Cotterell A. J.; Le G. T.; Fairlie D. P. Modulating human proteinase activated receptor 2 with a novel antagonist (GB88) and agonist (GB110). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 1413–1423. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J.; Iyer A.; Liu L.; Suen J. Y.; Lohman R. J.; Seow V.; Yau M. K.; Brown L.; Fairlie D. P. Diet-induced obesity, adipose inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction correlating with PAR2 expression are attenuated by PAR2 antagonism. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 4757–4767. 10.1096/fj.13-232702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman R. J.; Cotterell A. J.; Barry G. D.; Liu L.; Suen J. Y.; Vesey D. A.; Fairlie D. P. An antagonist of human protease activated receptor-2 attenuates PAR2 signaling, macrophage activation, mast cell degranulation, and collagen-induced arthritis in rats. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 2877–2887. 10.1096/fj.11-201004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman R. J.; Cotterell A. J.; Suen J.; Liu L.; Do A. T.; Vesey D. A.; Fairlie D. P. Antagonism of protease-activated receptor 2 protects against experimental colitis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 340, 256–265. 10.1124/jpet.111.187062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J. J.; Saifeddine M.; Triggle C. R.; Sun K.; Hollenberg M. D. 2-furoyl-LIGRLO-amide: a potent and selective proteinase-activated receptor 2 agonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 309, 1124–1131. 10.1124/jpet.103.064584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunanger P.; Vita-Finzi P. Heterocyclic Compounds - Isoxazoles 1999, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Kalgutkar A. S.; Nguyen H. T.; Vaz A. D.; Doan A.; Dalvie D. K.; McLeod D. G.; Murray J. C. In vitro metabolism studies on the isoxazole ring scission in the anti-inflammatory agent lefluonomide to its active alpha-cyanoenol metabolite A771726: mechanistic similarities with the cytochrome P450-catalyzed dehydration of aldoximes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 1240–1250. 10.1124/dmd.31.10.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobeli I.; Price S. L.; Lommerse J. P. M.; Taylor R. Hydrogen bonding properties of oxygen and nitrogen acceptors in aromatic heterocycles. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 2060–2074. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maryanoff B. E.; Santulli R. J.; McComsey D. F.; Hoekstra W. J.; Hoey K.; Smith C. E.; Addo M.; Darrow A. L.; Andrade-Gordon P. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2): structure-function study of receptor activation by diverse peptides related to tethered-ligand epitopes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 386, 195–204. 10.1006/abbi.2000.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry S. R.; Xu W.; Wirija A.; Lim J.; Yau M. K.; Stoermer M. J.; Lucke A. J.; Fairlie D. P. Three Homology Models of PAR2 Derived from Different Templates: Application to Antagonist Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 1181–1191. 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry G. D.; Suen J. Y.; Low H. B.; Pfeiffer B.; Flanagan B.; Halili M.; Le G. T.; Fairlie D. P. A refined agonist pharmacophore for protease activated receptor 2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5552–5557. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeney J. S.; Reid R. C.; Le G. T.; Fairlie D. P. Nonpeptidic ligands for peptide-activated G protein-coupled receptors. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2960–3041. 10.1021/cr050984g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen J. Y.; Cotterell A.; Lohman R. J.; Lim J.; Han A.; Yau M. K.; Liu L.; Cooper M. A.; Vesey D. A.; Fairlie D. P. Pathway-selective antagonism of proteinase activated receptor 2. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 4112–4124. 10.1111/bph.12757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asokananthan N.; Graham P. T.; Fink J.; Knight D. A.; Bakker A. J.; McWilliam A. S.; Thompson P. J.; Stewart G. A. Activation of protease-activated receptor (PAR)-1, PAR-2, and PAR-4 stimulates IL-6, IL-8, and prostaglandin E2 release from human respiratory epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 3577–3585. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N. The inflammatory response. Drug Dev. Res. 2003, 59, 375–381. 10.1002/ddr.10306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R.; Morice A. H.; Compton S. J. Proteinase-activated receptor2 agonists upregulate granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, IL-8, and VCAM-1 expression in human bronchial fibroblasts. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2006, 35, 133–141. 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0362OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesey D. A.; Kruger W. A.; Poronnik P.; Gobe G. C.; Johnson D. W. Proinflammatory and proliferative responses of human proximal tubule cells to PAR-2 activation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2007, 293, F1441–1449. 10.1152/ajprenal.00088.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.