Abstract

Picornaviruses constitute a medically important family of RNA viruses in which genome replication critically depends on a small RNA element, the cis-acting replication element (cre), that templates 3Dpol polymerase-catalyzed uridylylation of the protein primer for RNA synthesis, VPg. We report the solution structure of the 33-nt cre of human rhinovirus 14 under solution conditions optimal for uridylylation in vitro. The cre adopts a stem-loop conformation with an extended duplex stem supporting a novel 14-nt loop that derives stability from base-stacking interactions. Base-pair interactions are absent within the loop, and base substitutions within the loop that favor such interactions are detrimental to viral RNA replication. Conserved adenosines in the 5′ loop sequence that participate in a slide-back mechanism of VPg-pUpU synthesis are oriented to the inside of the loop but are available for base templating during uridylation. The structure explains why substitutions of the 3′ loop nucleotides have little impact on conformation of the critical 5′ loop bases and accounts for wide variation in the sequences of cres from different enteroviruses and rhinoviruses.

Keywords: stem-loop, uridylylation

The Picornaviridae comprise a large and diverse group of animal viruses possessing a monopartite RNA genome of positive polarity. They share a similar genome organization, with relatively lengthy 5′ and 3′ nontranslated regions (NTRs) flanking a single ORF. Whereas conserved RNA structures at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the genome contribute to recognition of the RNA by the viral replicase and thus specific amplification of viral and not cellular RNAs, an internally located, cis-acting replication element (cre) is also present within the ORF of human rhinovirus 14 (HRV-14) (Fig. 1a Upper) (1, 2). Similar cres are also present in the genomic RNAs of poliovirus and other viruses representing the other major picornaviral genera (3-7). These cres possess different nucleotide sequences and are positioned in different regions of the viral genome (1, 3-7), but all presumably serve identical functions in viral RNA replication. Studies with poliovirus indicate that the cre serves to template the uridylylation of VPg, a small viral protein that primes the initiation of RNA synthesis, in a reaction catalyzed by 3Dpol, the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (7-11).

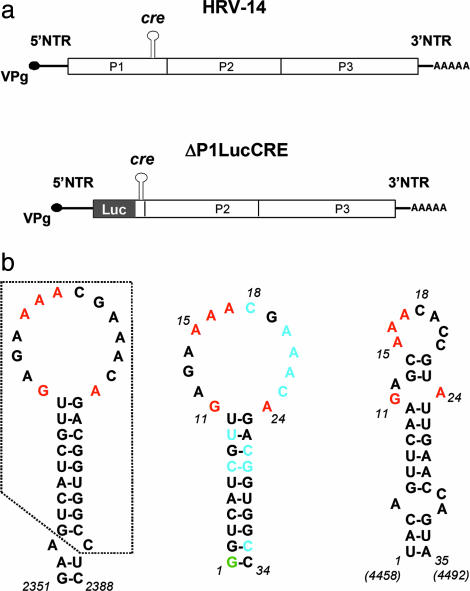

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the HRV-14 genome and replicon and predicted cre structures. (a) (Upper) Organization of the HRV-14 genome showing the position of the critical internally located cre that is required for RNA replication. The polyprotein-coding region is indicated by the open box, with its three major segments P1 (capsid proteins), P2, and P3 (replicase proteins) identified. (Lower) Schematic of the subgenomic HRV-14 ΔP1LucCRE replicon (2) used for replication studies. Most of the capsid protein sequence is replaced with the luciferase (Luc) coding sequence, and replication is monitored by assaying for luciferase after transfection of HeLa cells. (b) Nucleotide sequences and mfold-predicted secondary structures of the HRV-14 and poliovirus cres. (Left) Predicted secondary RNA structure in the region spanning nucleotides 2351-2388 within the P1 segment of the HRV-14 genome (2). The minimal functional cre (10) comprises the boxed sequence. Nucleotides within the cre loop that have been shown by mutational analysis to be critical for VPg uridylylation and RNA replication are shown in red (10). (Center) Predicted secondary structure of RNA transcripts subjected to NMR analysis (Δg = -8.8 kcal/mol). A 5′ terminal G (green) was added to the minimal cre sequence to facilitate RNA synthesis by the T7 polymerase; the two G:C base pairs at the end of the stem also reduce the possibility of end-fraying. Residues shown in blue are those that adopt C2-endo sugar puckering in the structural model. (Right) Predicted secondary structure of the functionally related cre located between nucleotides 4458 and 4492 within the P2 segment of the poliovirus genome (Δg = -5.0 kcal/mol). Conserved purine residues are highlighted in red.

The minimal functional HRV-14 cre resides within a 33-nt RNA segment that is predicted to form a simple stem-loop structure with a 14-nt loop and 9-bp stem (12) (Fig. 1b Left). Two consecutive adenosine residues within the 5′ half of the loop, and two residues, guanosine and adenosine, at the bottom of the loop, have been shown to be critically important for both VPg uridylylation and viral RNA replication (12). These residues appear to be conserved within the loop of the cre in other enteroviruses and rhinoviruses (12), despite the absence of significant sequence homology elsewhere in the cre. The two adenosine residues template the uridylyation of VPg in a two-step, slide-back mechanism for VPg-pUpU synthesis (10), but the basis of the requirement for the guanosine and adenosine residues at the base of the loop is unknown. Despite limited sequence identity, the HRV-14 and poliovirus RNA elements demonstrate a limited degree of functional exchangeability in both RNA replication and VPg uridylylation reactions (7, 13, 14). The ability of the poliovirus cre to substitute for the HRV-14 replication element in supporting viral RNA replication is enhanced by specific mutations within the nonstructural viral proteins, 3Dpol or 3Cpro (or possibly their precursor molecule, 3CD) (13). These cres are thus likely to share common, higher-ordered structural features that are important for their recognition by viral proteins involved in VPg uridylylation (5, 7, 13, 14).

Here, we report the use of NMR spectroscopy to determine the solution structure of the HRV-14 cre. We present the high-resolution structure of a functional picornaviral cre and provide a framework for understanding the natural variation that exists in cre sequences, as well as the ability of various HRV-14 cre mutants to direct VPg uridylylation and thus support viral RNA synthesis.

Materials and Methods

NMR Spectroscopy. Unlabeled and fully 13C/15N double-labeled RNA molecules as well as specifically labeled (A or C residue) samples were prepared by in vitro, run-off transcription of DNA templates by using phage T7 RNA polymerase. 2D NOESY, total correlation spectroscopy, and double quantum filtered spectroscopy spectra were collected on purified RNA samples at concentrations of 0.8-2.0 mM, at 10°C or 25°C, in either 100% D2O or 10%D2O/90% H2O, by using Varian UnityPlus 750 and 600-MHz instruments equipped with pulse field gradients. Further details are provided in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Structure Determination. Interproton distance restraints, obtained from 2D NOESY, and 3D 13C- or 15N-edited NOESY spectra, were used to define the cre structure. Most heteronuclear experiments were carried out with the Varian pulse sequence package, rnapack (15), optimized for RNA structure determination. Structures were calculated and refined by using protocols provided within the x-plor software package (16) (see Supporting Text). Coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (ID code 1T28), and chemical shifts were submitted to the BioMagResBank (accession code BMRB-6115).

RNA Folding Algorithm. Computer-based predictions of RNA structure used the mfold program of Zuker with default folding parameters (17).

HRV-14 RNA Replication Assay. The replication of HRV-14 RNA was monitored by measurement of luciferase expression in HeLa cells transfected with RNA transcribed from pΔP1LucCRE (2), a subgenomic replicon in which most of the HRV-14 P1 sequence has been replaced by the firefly luciferase coding sequence (Fig. 1a Lower). Further details of this and mutagenesis of the pΔP1LucCRE plasmid are provided in Supporting Text.

Results

NMR Spectroscopy of the HRV-14 cre. We analyzed the NMR spectra of synthetic RNA transcripts that were 34 nt in length and correspond to the sequence between nucleotides 2354 and 2386 of the HRV-14 genome (Fig. 1b Center). This sequence comprises the minimal functional HRV-14 cre, and it is capable of templating the uridylylation of VPg in vitro in reactions catalyzed by a picornaviral 3Dpol RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (12). An additional guanylate residue was added to the 5′ end of this sequence to facilitate transcription of both unlabeled and 15N/13C double-labeled RNAs for the NMR experiments. Spectral assignments and the extraction of structural constraints were achieved by using a combination of heteronuclear and homonuclear 2D and 3D NMR experiments (see Supporting Text).

This segment of the HRV-14 genomic RNA is predicted by mfold (17) to form a simple stem-loop structure containing a large 14-nt loop (Fig. 1b Center). The existence of this basic structure was confirmed by analysis of the NMR spectra. Exchangeable amino and imino protons were assigned from the homonuclear 2D NOESY and 15N-heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra, and the imino protons of guanosines and uridines were identified by separation in the 15N dimension in the 15N-HSQC spectra. These results showed seven strong guanosine imino resonances and six uridine imino resonances, all from the stem region (Fig. 6a, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Two weak G imino resonances (Fig. 6a, marked as x and y) were assigned to G1 and G11, but were not observed in the homonuclear 2D NOESY spectra. Sequential, base-paired imino-imino proton cross peaks were observed continuously throughout the stem region in the homonuclear 2D NOESY spectra (Fig. 6b). The cross-peaks pattern confirmed the presence of three predicted G:U base pairs in the stem. These were also apparent in the 15N-HSQC spectra optimized for amino protons (data not shown). Further details concerning the spectral assignments are presented in Materials and Methods.

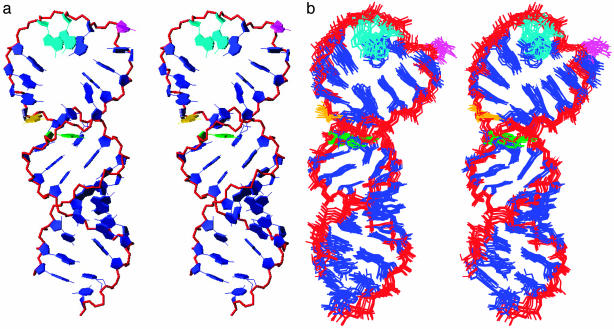

Solution Structure of the HRV-14 cre. A total of 454 inter-proton distance restraints and 142 torsion angle restraints were used to obtain a well defined tertiary fold of the cre at <2.0-Å resolution (Table 1). The final averaged structure (Fig. 2a) shows a knob-like domain comprised of a 10-bp stem connected by a spirally twisted, 14-nt loop, consistent with the input restraints. Despite being well defined by the rms deviation values (Table 1), the loop region is less well defined than the stem, as shown by an overlay of the 10 lowest energy structures (Fig. 2b). This variation is caused in part by the larger number of restraints in the stem region. Nonetheless, the large 14-nt loop exhibits significant structural stability as indicated by sequential inter-residue NOE connectivities and dispersion of the anomeric to aromatic region of NOESY spectra.

Table 1. Structural statistics for NMR solution structure of HRV-14 cre stem-loop.

| No. of restraints used for structure calculations* | |

| NOE-derived distance restraints | 454 |

| Interresidue | 175 |

| Intraresidue | 279 |

| Stem region (1-10, 25-34) | 345 |

| Loop region (11-24) | 109 |

| Dihedral restraints | 142 |

| Hydrogen bond restraints | 52 |

| rms deviations from experimental restraints | |

| Distance restraints, Å | 0.06 ± 0.003 |

| Dihedral restraints, ° | 0.89 ± 0.07 |

| Deviations from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bonds, Å | 0.004 ± 0.0001 |

| Angles, ° | 1.24 ± 0.01 |

| Heavy atom rms deviations (Å) relative to the mean structure | |

| All residues | 1.42 ± 0.31 |

| Loop region (residues 11-24) | 1.97 ± 0.37 |

| Stem region (residues 1-10; 25-34) | 1.15 ± 0.16 |

The final structures contained fewer than three distance restraint violations >0.2 Å and no dihedral angle violations per structure.

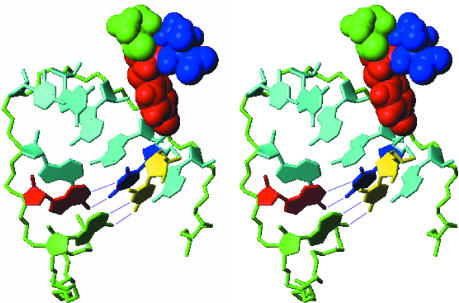

Fig. 2.

Structure of the HRV-14 cre. (a) Stereoview of the final averaged structure of the HRV-14 cre, with the loop oriented to the top of the structure. The spirally twisted 14-nt loop is supported by a 10-bp stem containing three G:U base pairs. In nature, this stem is likely to have only nine base pairs because of the absence of G1 (Fig. 1b Center) in the native sequence. The phosphate backbone is shown in red. Residues are shown in blue except for: A15 and A16 (turquoise), which template uridylylation; C18 (magenta), which is looped out, causing a break in the stacking pattern; and G11 (yellow) and A24 (green), the first unpaired residues at the stem-loop junction. (b) Stereoview of the superposition of the final 10 lowest energy structures of the HRV-14 cre. The loop is less well defined than the stem, possibly reflecting greater flexibility of this part of the structure. Colors are as in a.

The loop appears to derive its stability from stacking interactions between bases in both of its halves. C18 is located in the middle of the loop and is not stacked, but rather looped outward (Fig. 2a). This looped-out cytosine residue is crucial for the structure of the loop, because it causes a break in the stacking of bases, allowing the adenosine residues on the 5′ side of the loop (A14-A17) to stack on each other and the residues on the 3′ side of the loop to stack in the opposite direction (Fig. 2a). This cytosine is conserved in many enterovirus and rhinovirus cres. It can be replaced with uracil without significant loss of function, but not adenine or guanine (12). The structure shown in Fig. 2a explains why nucleotide substitutions within the 3′ half of the loop have little impact on cre function (12), as they would have little influence on the structure of the critical 5′ half of the loop. In contrast, residues A15 and A16 on the 5′ side of the loop are absolutely conserved and critical for cre function in both VPg uridylylation and viral RNA replication (12, 18). The residues in the 3′ half of the loop thus play a supporting role through promoting stable base stacking and preventing formation of intraloop base pairs.

The presence of several scalar cross peaks in the double quantum filtered spectroscopy spectra in the H1′-H2′ region suggest that several residues within the loop and stem regions adopt C2-endo sugar puckering, as commonly observed in B-form DNA helices (Fig. 1b Center). These include the U residues in the G:U pairs within the stem. Phosphorus chemical shifts for the phosphates were observed between -3.6 and -4.5 ppm (referenced to trimethylphosphate at 0.0 ppm, data not shown). This narrow, 0.9-ppm range in the 31P NMR spectrum indicates that all of the phosphates are in the normal AI sugar phosphate conformation (19). However, because of heavy overlap of 31P signals, it was not possible to make unambiguous assignments of individual phosphorus resonances.

Effect of Mg2+ Concentration on cre Structure. Metal ions, such as Mg2+, may be important to the folding of RNA molecules (20). The efficiency of poliovirus 3Dpol uridylylation of VPg templated by the poliovirus cre in vitro is also highly influenced by Mg2+ concentration and is optimal at ≈3.6 mM Mg2+ (21). To ascertain whether the Mg2+ concentration influences the cre structure, we collected NMR spectra of RNA transcripts over concentrations of Mg2+ ranging from 0.4 to 3.6 mM. We observed no Mg2+ concentration-dependent perturbations in the NMR spectra, indicating that the variation observed in uridylylation efficiency in vitro at different concentrations of Mg2+ is not related to Mg2+-dependent changes in conformation of the cre. The Mg2+ dependency of uridylylation is thus more likely to reflect a requirement for metal cations by the 3Dpol enzyme that catalyzes this reaction.

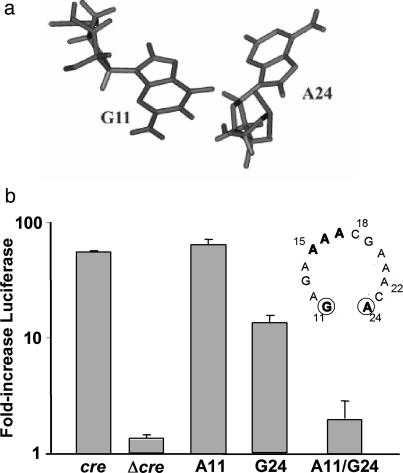

Functional Impact of Base-Pair Interactions at the Stem-Loop Junction. In addition to the A15 and A16 residues, the two bases at the junction of the stem and loop, G11 and A24 (Fig. 1b), are essential for cre function. Pyrimidine substitutions of either of these residues are highly detrimental to uridylylation, whereas substitution of either with the complementary purine is relatively well tolerated (12). Although the final refined structure indicates that G11 and A24 are in close proximity (Fig. 2a), the orientation of the bases does not allow the formation of hydrogen bonds between potential donor-acceptor groups (Fig. 3a). Because conformation of the loop is likely to be critical for proper presentation of A15 and A16 to the uridylylation complex, as discussed above, we considered the possibility that alterations in the conformation of the loop related to hydrogen bonding between bases 11 and 24, at the junction of the loop and stem, might explain the previously observed lack of cre activity in mutants containing C11, or C24 or U24 substitutions (12). A similar situation would be predicted for a mutant in which the WT G11 and A24 residues were reversed (i.e., a cre containing A11 and G24), as this orientation would potentially position the donor-acceptor atoms in an orientation conducive to formation of hydrogen bonds.

Fig. 3.

Junction of the HRV-14 cre stem and loop. (a) Structure of the first base mismatch at the stem-loop junction, showing G11 and A24. Although these two bases are in close proximity, the formation of hydrogen bonds is not possible because of the orientation of the donor-acceptor groups. (b) Influence of base substitutions at G11 and A24, including reversal of these two bases, within the cre of HRV-14 on RNA replication in the context of the subgenomic replicon, ΔP1LucCRE (see Fig. 1a). Replication was assessed by measuring the increase in luciferase activity (± SEM in triplicate assays) between 3 and 24 h after transfection of RNAs into HeLa cells, normalized to that observed with WT ΔP1LucCRE replicon (cre = 100%) (10). The replicon Δcre does not contain a cre and thus serves as a negative control. (Inset) Shown are the WT loop sequence and the position of the G11 and A24 residues at the bottom of the loop.

To test this hypothesis, we altered the sequence of the cre within the subgenomic HRV-14 RNA replicon, ΔP1LucCRE (Fig. 3b), by constructing two single-base mutants, A11 and G24, and one double-base mutant, A11/G24. This replicon contains a functional cre and is amplified autonomously when transfected into HeLa cells (Fig. 1a Lower) (2). Because it contains the luciferase sequence in lieu of the viral capsid sequences, it directs the expression of luciferase proportional to its replication efficiency. We observed that replicons with combinations of bases at these two positions that do not favor hydrogen-bond formation (i.e., the WT G11/A24 cre, and the single-base mutants A11 and G24) all caused an increase in luciferase expression between 3 and 24 h after transfection (Fig. 3b), although the G24 substitution reduced replication capacity to ≈10% that of the WT. This finding indicates that these cre sequences are functional and can support VPg uridylylation and therefore replication of the RNA (12). In contrast, transfection of the replicon containing both base substitutions, A11/G24, resulted in a negligible increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 3b), indicating that this mutated cre was unable to support RNA replication (12). These results provide support for the hypothesis that base-pairing is poorly tolerated at the bottom of the loop and prevents the cre from properly templating the uridylylation of VPg.

Functional Significance of Base-Pair Interactions Within the cre Loop. The final averaged structure shown in Fig. 2a suggests that base-pairing does not occur within the loop of the HRV-14 cre. In contrast, mfold (17) predictions suggest that the loops of the phylogenetically related poliovirus and HRV-2 cres are considerably smaller than the 14-nt HRV-14 cre loop because of the presence of 2-3 base pairs within the functionally homologous sequences (see Fig. 1b Right) (4, 5, 10, 12). However, because the HRV-14 and poliovirus cres share a considerable degree of functional interchangeability (7, 13, 14), these RNA elements are likely to assume a similar tertiary structure. Thus, if the model shown in Fig. 2a accurately reflects the functional HRV-14 RNA element, the additional base pairs shown in the predicted poliovirus cre structure (Fig. 1b Right) are unlikely to be present in the poliovirus cre. On the other hand, although they are not present in the final averaged structure (Fig. 2a), there is a possibility for two stacked non-Watson-Crick G:A/A:G base pairs to form within the center of the HRV-14 loop (Fig. 4). These G:A/A:G pairings would produce a structure similar to that predicted for the poliovirus cre, albeit with a smaller loop. Thus, an alternative possibility is that the final refined structure does not reflect the biologically active HRV-14 molecule. Significantly, such tandem G:A base pairs are commonly observed in RNAs, although their stability is difficult to predict.

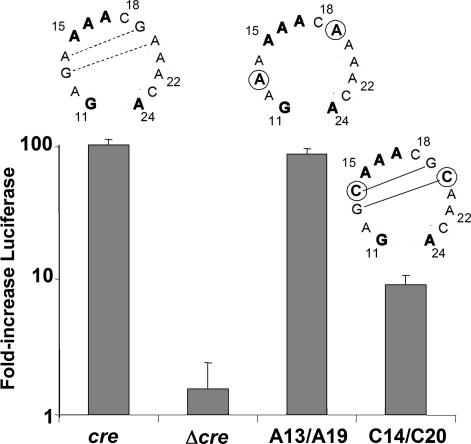

Fig. 4.

Relative replication capacities of subgenomic ΔP1LucCRE RNAs containing the WT cre sequence (cre) or cres with base substitutions that alter the stability of potential base-pairing within the loop sequence. Replication competence was assessed as in Fig. 3b. Above each bar is shown the loop sequence tested. Mutated bases are circled; lines connecting bases indicate potential base-pair interactions. The mfold-predicted free energy of the structure predicted for the C14/C20 cre is -11.6 kcal/mol.

To validate the functional relevance of the structure shown in Fig. 2a and gain insight into the functional significance, if any, of base-pairing within the cre loop, we examined the effect of varying the stability of such intraloop base-pairings on the function of the HRV-14 cre. To accomplish this, we constructed two additional cre mutants in the context of the ΔP1LucCRE replicon, each of which contained two nucleotide substitutions, C14/C20 or A13/A19 (Fig. 4). mfold (17) predictions suggest that the C14/C20 substitutions result in two intraloop G:C base pairs involving residues 13:20 and 14:19 (Fig. 4). In contrast, no intraloop base-pairing is predicted for the A13/A19 substitutions, in which the possible G:A/A:G pairings are disrupted. Importantly, each of these individual base changes has been shown previously to be permissible as a single base substitution in the cre and to be without adverse impact on either uridylylation or RNA replication (12). Significantly, the replicon containing the C14/C20 substitutions within the cre was reduced ≈90% in its replication capacity (Fig. 4). In contrast, the dual A13/A19 substitutions were well tolerated and had no apparent impact on RNA replication. This result supports the proposed structural model, in which the large loop structure is stabilized by stacking interactions, and indicates that substitutions that provide stability to intraloop base-pairing are detrimental to cre function.

Discussion

Viruses in the family Picornaviridae have proven to be extraordinarily useful in dissecting the mechanisms of replication of positive-strand RNA viruses. The cre plays a central role in this process for picornavirusess, as it templates a critical reaction that produces the protein primer for viral RNA synthesis, VPg-pUpU (7, 10, 21). Although every picornavirus appears to contain such an RNA element, its location within the genome and nucleotide sequence vary widely among different picornaviruses, even among picornaviruses belonging to genera that are closely related phylogenetically, such as the enteroviruses and rhinoviruses (1, 3-7). Nonetheless, there is substantial evidence to support the hypothesis that these cres contain a common, higher-ordered structure that is essential to its role in VPg uridylyation (13, 14, 21). We present here the high-resolution structure of a picornaviral cre. Its structural features provide insight into the molecular events occurring during VPg uridylylation, but they are also of interest from a structural perspective. Although the solution structures of many small-loop hairpins have been solved by NMR, little structural information is available concerning hairpins containing loops of nine or more unpaired nucleotides.

A striking feature of the HRV-14 cre is the large open loop with 14 unpaired nucleotides. The mutational analysis shown in Fig. 4 confirms the functional importance of this open loop structure, as mutations that are predicted to result in base-pairing within the loop were very detrimental to viral RNA replication. The functional interchangeability of the HRV-14 and poliovirus cre sequences both in uridylylation and viral RNA replication suggests a common basic structure for these RNA elements, making it likely that the base-pairing predicted within the poliovirus cre does not form under physiologic conditions. In agreement with these results, Goodfellow et al. (22) were unable to detect the mfold-predicted internal base pairs within the poliovirus cre loop by either enzymatic or chemical probing. Furthermore, Paul et al. (21) recently reported that a single base substitution that eliminated such predicted base-pairing did not impair the ability of the poliovirus cre to template VPg uridylylation. In contrast, mutations that made the predicted poliovirus loop smaller were highly detrimental, consistent with the impaired RNA replication we noted with substitutions in the HRV-14 cre that favored base-pair formation within the loop (C14/C20 mutant, Fig. 4).

To gain an appreciation of the poliovirus cre structure, we collected 1D NMR spectra, at different temperatures, of an RNA transcript representing the poliovirus cre. Although this RNA was similar in length to the HRV-14 transcript, spectral resonances were broad and not as well resolved (data not shown). These preliminary results are consistent with the poliovirus molecule not forming a single, well defined structure, possibly because of the internal loop within the stem (Fig. 1b Right).

These results suggest that a large and relatively flexible loop is a requirement for efficient templating of the VPg uridylylation reaction, and that considerable stability derives from the stacking interactions of the bases on the 5′ and 3′ halves of this loop. The mfold-predicted free energy associated with the poliovirus cre structure shown in Fig. 1b Right is -5.0 kcal/mol, whereas that associated with the fully functional cre mutant (21) in which a single base substitution eliminated the predicted internal base-pairing is only -0.8. kcal/mol. This energy difference is likely to be overcome by stacking interactions within these large loops, or possibly through interactions of the cre RNA with the viral polymerase (3Dpol) or the protease-polymerase precursor (3CD) that acts to promote the uridylylation reaction (7, 13, 21).

A GA first base-pair mismatch is commonly observed in tetraand 6-nt loops and contributes to loop stability through hydrogen bonding (23, 24). Interestingly, this GA first mismatch is strongly conserved among the cres of rhinoviruses and enteroviruses, and these bases cannot be substituted with pyrimidines without significant loss of function (12, 14). However, no NOESY cross peaks were detected between the amino protons of A24 and the imino or the amino protons of G11, indicating the absence of imino-hydrogen bonds or sheared type interactions between these two residues despite their close proximity (Fig. 3a). The lack of hydrogen bonding between G11 and A24 imposes no constrains on the phosphate backbone and thus might facilitate any loop conformational changes required for uridylylation. Reversal of these bases (A11/G24, Fig. 3b) is severely detrimental to uridylylation, possibly because of subsequent hydrogen bond formation between these bases.

During the 3Dpol-catalyzed slide-back uridylylation of VPg, A15 (Fig. 1b Left) serves as template for the first UTP to be coupled to the third residue, Tyr, of VPg (7, 10). The resulting VPg-pU complex then slides in a 3′ direction, resulting in the VPg-coupled uridine residue becoming paired with A16. A15 then templates the addition of a second UTP, resulting in VPg-pUpU, the protein primer for viral RNA synthesis (11). The A15 and A16 residues are thus involved in dynamic interactions with 3Dpol, UTP, and both nonuridylylated and uridylylated VPg. It might be expected, therefore, that A15 and A16 would face outward from the loop, with the Watson-Crick interaction edges exposed to the solvent and available for base-pairing with UTP. Surprisingly, however, this is not the case in the final refined structure of the cre (Fig. 2a), in which these adenosine residues are oriented to the inside of the loop. However, the cre loop is twisted in a spiral fashion such that sufficient space is provided for the two uridine residues to base-pair with A15 and A16 without significant disruption of the structure. To visualize this, we constructed a model of the cre base-paired with the two uridine residues present in the fully uridylyated VPg-pUpU molecule (Fig. 5). The rms deviation calculated for the loop of the cre (residues G11-A24) in this model showed a difference from the baseline conformation of only 2.16 Å from the final averaged structure. The twist in the loop that makes this possible places the two base-paired uridine residues in relatively close proximity to A21 and A22, but otherwise outside of the curved plane formed by the base-stacking interactions within the 3′ half of the loop (Fig. 5). Specific interactions between the uridine residues and A21 and A22 seem unlikely, however, because these latter residues are not conserved in the poliovirus cre (Fig. 1b) and can be replaced in the HRV-14 cre without significant loss of function (12). Because the loop appears to be relatively flexible (Fig. 2b), this arrangement would appear to facilitate the dynamic interactions between the first uridine to be covalently bound to VPg, the cre RNA, and 3Dpol that are necessary for slide-back templating of the uridylylation reaction.

Fig. 5.

Stereoview of a model showing potential base-pairing between pUpU and the critical adenosine residues of the cre that template uridylylation. The middle segment of the loop is shown with the A15 (green) and A16 (red) residues forming conventional Watson-Crick base pairs with pUpU (yellow and blue). The polypeptide component of VPg is coupled to the uppermost uridine residue (blue) in this view. The tyrosine residue of VPg (red) is shown, with the flanking residues, Ala (green) and Thr (blue), also shown in the model. The phosphate backbone of the cre loop is green, and residues A17-A22 are cyan.

An alternative possibility is that a conformational rearrangement of the loop is necessary for the uridylylation reaction to proceed. Protein binding often induces significant RNA conformational changes, and 3Cpro or 3CD is essential for efficient 3Dpol-mediated VPg uridylylation (10, 14, 25). Thus it is possible that an interaction between 3Cpro or 3CD and the cre facilitates a conformational change, reorienting the adenosines outward so they are more readily available to template the uridylylation reaction. Several residues within the upper portion of the stem adopt C2′-endo sugar puckering, as commonly observed in B-form DNA helices (Fig. 1b Center). This feature would make the top part of the major groove of the cre helix relatively wide and shallow and thus more accessible for ligand binding (26). Consistent with this structural information, recent studies suggest that the stem of the cre is involved in its interaction with 3CD and/or 3Dpol (13, 14). Ultimately, a determination of the structure of the cre in complex with 3Dpol or 3CD and VPg will be required to establish whether a conformational change in the cre loop occurs upon binding of these proteins and is necessary for VPg uridylylation. This may be technically difficult, however, as these interactions have proven difficult to characterize by conventional approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI140282 (to S.M.L.) and AI27744 and ES06676 (to D.G.G.) and a grant from The McLaughlin Endowment (to Y.Y.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: cre, cis-acting replication element; HRV-14, human rhinovirus type 14; NTR, nontranslated region.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 1T28), and the NMR chemical shifts have been deposited in the BioMagResBank, www.bmrb.wisc.edu (accession no. BMRB-6115).

References

- 1.McKnight, K. L. & Lemon, S. M. (1996) J. Virol. 70, 1941-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKnight, K. L. & Lemon, S. M. (1998) RNA 4, 1569-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lobert, P. E., Escriou, N., Ruelle, J. & Michiels, T. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 11560-11565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodfellow, I., Chaudhry, Y., Richardson, A., Meredith, J., Almond, J. W., Barclay, W. & Evans, D. J. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 4590-4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerber, K., Wimmer, E. & Paul, A. V. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 10979-10990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason, P. W., Bezborodova, S. V. & Henry, T. M. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 9686-9694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul, A. V., Rieder, E., Kim, D. W., van Boom, J. H. & Wimmer, E. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 10359-10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flanegan, J. B., Petterson, R. F., Ambros, V., Hewlett, N. J. & Baltimore, D. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74, 961-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee, Y. F., Nomoto, A., Detjen, B. M. & Wimmer, E. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74, 59-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul, A. V., Yin, J., Mugavero, J., Rieder, E., Liu, Y. & Wimmer, E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43951-43960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul, A. V., van Boom, J. H., Filippov, D. & Wimmer, E. (1998) Nature 393, 280-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang, Y., Rijnbrand, R., McKnight, K. L., Wimmer, E., Paul, A., Martin, A. & Lemon, S. M. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 7485-7494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang, Y., Rijnbrand, R., Watowich, S. & Lemon, S. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12659-12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin, J., Paul, A. V., Wimmer, E. & Rieder, E. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 5152-5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lukavsky, P. J. & Puglisi, J. D. (2001) Methods 25, 316-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brünger, A. T. (1993) x-plor: A System for X-Ray Crystallography and NMR (Yale Univ., New Haven, CT), Version 3.1.

- 17.Zuker, M. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieder, E., Paul, A. V., Kim, D. W., van Boom, J. H. & Wimmer, E. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 10371-10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorenstein, D. G. (1994) Chem. Rev. 94, 1315-1338. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pyle, A. M. (2002) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 7, 679-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul, A. V., Peters, J., Mugavero, J., Yin, J., van Boom, J. H. & Wimmer, E. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 891-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodfellow, I. G., Kerrigan, D. & Evans, D. J. (2003) RNA 9, 124-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serra, M. J., Axenson, T. J. & Turner, D. H. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 14289-14296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fountain, M. A., Serra, M. J., Krugh, T. R. & Turner, D. H. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 6539-6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pathak, H. B., Ghosh, S. K., Roberts, A. W., Sharma, S. D., Yoder, J. D., Arnold, J. J., Gohara, D. W., Barton, D. J., Paul, A. V. & Cameron, C. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31551-31562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weeks, K. M. & Crothers, D. M. (1993) Science 261, 1574-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.