Abstract

The Arabidopsis var2 variegation mutant defines a nuclear gene for a chloroplast FtsH metalloprotease. Leaf variegation is expressed only in homozygous recessive plants. The cells in the green leaf sectors of this mutant contain morphologically normal chloroplasts, whereas cells in the white sectors contain abnormal plastids lacking organized lamellar structures. var2 mutants are hypersusceptible to photoinhibition, and VAR2 degrades unassembled polypeptides and is involved in the D1 repair cycle of photosystem II, likely by affecting turnover of the photodamaged D1 polypeptide. A second-site suppressor screen of var2 yielded a normal-appearing, nonvariegated line. Map-based cloning revealed that the suppression of variegation in this line is due to a splice site mutation in ClpC2, a chloroplast Hsp100 chaperone, that results in sharply reduced ClpC2 protein accumulation. Isolation of clpC2 single mutants showed that clpC2 is epistatic to var2, and that a lack of ClpC2 does not markedly alter the composition of the thylakoid membrane. Suppression by clpC2 is not allele-specific. Our results suggest that clpC2 is a suppressor of thylakoid biogenesis and maintenance and that ClpC2 might act by accelerating photooxidative stress. Arabidopsis has two ClpC genes (ClpC1 and ClpC2), and mutants with down-regulated expression of both genes have a phenotype different from clpC2, suggesting that ClpC1 and ClpC2 act synergistically and/or that they are only partially redundant. The isolation of a clpC2 mutant represents an important advance in the generation of tools to understand Hsp100 function and insight into the mechanisms of protein quality control in plants.

Protein concentrations within all compartments of the eukaryotic cell are regulated by various mechanisms of protein quality control (1, 2). Chaperones and ATP-dependent proteases are important components of these surveillance systems. In chloroplasts, protein quality control is mediated, in part, by three classes of ATP-dependent proteases that also have chaperone activities: Clp, Lon, and FtsH (3-5). The regulatory (ATPase) and proteolytic domains are located on separate subunits in Clp, whereas in FtsH and Lon they reside on the same polypeptide. These three proteases are evolutionarily derived from the prokaryotic-like ancestors of chloroplasts. A major unanswered question is how the various proteases and chaperones interact to provide an integrated network of protein quality control in the plastid.

Photosynthetic organs of the Arabidopsis var2 variegation mutant have green sectors with cells that contain normal-appearing chloroplasts and white sectors with cells that have abnormal plastids lacking organized lamellar structures (6, 7). This mutant defines a nuclear recessive gene for a plastid-localized FtsH homolog (designated AtFtsH2) (8, 9). FtsH genes comprise small multigene families in plants, and the products of these genes are targeted to both plastids and mitochondria (10-12). Arabidopsis contains 12 AtFtsH genes, including three pairs of closely related proteins that are targeted to the plastid and are functionally redundant, at least in part (11). These functions are not well characterized but include degradation of unassembled Rieske FeS proteins in the thylakoid membrane (13) and involvement in the D1 repair cycle, during which photodamaged D1 proteins of photosystem II are replaced with new copies (4, 12, 14-16). One of the fascinating questions about var2 concerns the mechanism underlying its peculiar, chaotic pattern of variegation: How do normally appearing green sectors arise in a uniform (mutant) genetic background?

To gain insight into FtsH function and the mechanisms of var2 variegation, we embarked on a mutagenesis screen to isolate second-site suppressors that modulate the variegation phenotype of var2. A number of mutants were isolated in which the pattern of variegation was much reduced. Here, we report on the map-based cloning of a suppressor that had a wild-type-looking phenotype and show that it defines the gene for ClpC2, a Hsp100 chaperone. Because reductions in ClpC2 suppress the requirement for FtsH in thylakoid membrane biogenesis, our data suggest that clpC2 is a negative regulator of this process. We present a model consistent with the hypothesis that ClpC2 accelerates the effects of photoinhibition caused by mutations in FtsH.

Methods

Plant Material and Map-Based Cloning. The Arabidopsis variegation mutants used in this study and procedures for their growth and maintenance have been described in refs. 7 and 17. For the suppressor analyses, var2-5 seeds were mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate and ≈50,000 M2 seeds were screened for nonparental phenotypes. One of the strains (termed ems2544) was selected for further study, and the suppressor gene in this strain was mapped by bulk-segregation analysis (18) by using a pool of ≈100 F2 seedlings from a cross of ems2544 with Landsberg erecta. The gene was mapped by using sets of codominant simple sequence-length polymorphism (SSLP) markers (19), as well as cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS), and derived CAPS markers that were designed by using the Cereon Genomics Indel or single-nucleotide polymorphism databases (20). Molecular markers used for mapping are listed as supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site. Other procedures for map-based cloning have been described in ref. 8.

To generate sense or antisense ClpC2 constructs, a cDNA that contained the entire 2.8-kbp ClpC2 coding sequence was isolated by RT-PCR by using the primers AGCCTCTAGAATTGCATCATGGCTTGGTCG and ACCTCTAGATTCCTTCTACAATATTGGAATAG (XbaI sites in italic). The sequences were then cloned in the forward and reverse orientations behind the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter into the XbaI site of pBI121 to generate sense and antisense ClpC2 transgenes. Transgenic plants were obtained by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation by using the procedures described in ref. 11.

Nucleic Acid and Protein Manipulations. Procedures for purification of genomic DNA and total RNA and for Northern blotting and RT-PCR analyses have been described in ref. 11. Molecular markers used in the RT-PCR experiments are listed as supporting information.

Intact chloroplasts were isolated by using a two-step Percoll gradient (40% and 80%), as described in ref. 21. The band that appeared between the phases was collected, washed, and resuspended in a buffer containing 0.33 M sorbitol and 50 mM Hepes (pH 8.0); chlorophyll concentrations were measured on the resuspended plastids (22). Western immunoblot analyses were conducted by using either total chloroplasts or membrane fractions, and the proteins were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (11).

To generate polyclonal antibodies, nucleotide fragments corresponding to P711-L952, P196-G353, A51-S229, and G367-V507 of ClpC2, D1, PetC, and ATPA, respectively, were sub-cloned into the pET15b vector (Novagen), and the resulting constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) (Novagen). All of the expressed peptides formed inclusion bodies, which were purified and solubilized and then injected into rabbits. After three injections, cleared sera were used as antibodies against each antigen. Specific ClpC1 and ClpC2 antisera were raised against synthetic peptides, GGSGTPTTSLEEQ and GTTGRVGGFAAEEAM, respectively (ProSci, Poway, CA). In some experiments a VAR2 polyclonal was used (8). This antibody was raised against the C-terminal third (232 aa) of VAR2.

Results

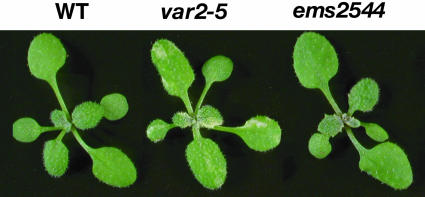

Isolation and Map-Based Cloning of a var2 Second-Site Suppressor. var2-5 is one of the weakest var2 alleles and has a missense mutation (P320L) in Walker ATP binding site B (8). To identify second-site suppressors, var2-5 seeds were mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate, and 54 M2 progeny lines were identified that had modified variegation phenotypes. One plant with all-green leaves was selected for further analysis (designated ems2544) (Fig. 1). Whereas the leaves in this line are not variegated, they are darker green than normal and aberrantly shaped.

Fig. 1.

Wild type (Columbia), var2-5, and ems2544. The plants were germinated at the same time and maintained under continuous light [100 microeinsteins (1 einstein = 1 mol of light) per m2·sec-1] for 12 days.

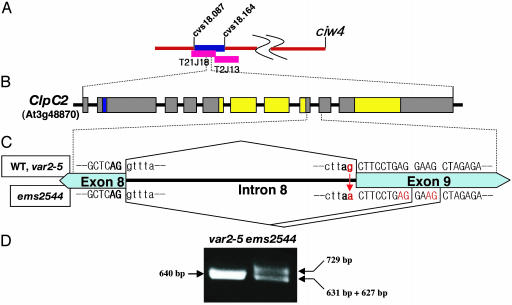

To clone the suppressor gene in ems2544, a F2 mapping population was generated by crossing ems2544 with Landsberg erecta. Bulk-segregation analyses revealed that the suppressor phenotype cosegregated with SSLP marker ciw4 on the lower arm of chromosome 3 (Fig. 2A). To fine-map the gene, 1,868 F2 individual chromosomes were screened by using SSLP, CAPS, and derived CAPS markers, and the suppressor gene was found to reside within an ≈77-kbp region of chromosome 3 that contains 21 annotated ORFs (Fig. 2 A). cDNAs from each ORF were amplified from total cell RNAs of ems2544 and var2-5 by using a series of overlapping, gene-specific primers to each ORF, and the RT-PCR products were sequenced. One ORF (annotated At3g48870) was found that had a PCR product with a G→A transition in the 3′-splice site of the eighth intron of the gene in ems2544 (Fig. 2 B and C). The predicted size of this ORF is 105 kDa (952 aa), and it contains 10 exons and a predicted chloroplast targeting sequence (Fig. 2B). From the annotated Arabidopsis sequence, this ORF is the gene for ClpC2, a HSP100 chaperone. Hsp100 chaperones such as ClpC2 can act alone or as regulatory subunits of the Clp protease (3, 23, 24). There are two nuclear ClpC genes in Arabidopsis (ClpC1 and ClpC2), both of which appear to code for plastid proteins. Like other ClpC proteins, ClpC2 is a class 1 Hsp100, with two distinct but conserved nucleotide-binding domains that contain classic Walker ATP-binding sites A and B (23, 25, 26) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Map-based cloning of the var2 suppressor gene. (A) SSLP markers were used to map the suppressor gene in ems2544 to the ciw4 region of chromosome 3. The gene was fine-mapped to an ≈77-kbp interval between markers cvs18.087 and cvs18.164 (supporting information). This region is covered by two bacterial artificial chromosome clones, T21J18 and T2J13. (B) ClpC2 is composed of 10 exons (boxes), with a predicted chloroplast targeting sequence (blue) and two nucleotide-binding domains (yellow). (C) The splice site mutation is located at the 3′ end of the eighth intron of clpC2: the wild-type and var2 premRNAs are spliced normally (upper), whereas ems2544 has three differentially spliced mRNAs (lower). (D) RT-PCR analyses were conducted on mRNAs from var2-5 and ems2544 plants, and the products were electrophoresed on an 0.8% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

To further define the nature of the lesion in clpC2, the RT-PCR experiments were repeated by using primers to exon 6 and exon 10. In contrast to the normally spliced mRNAs, which are found in the wild type and var2-5 (represented by the 640-bp PCR product) (Fig. 2 C and D), sequencing of RT-PCR products from ems2544 revealed that the splice site mutation generates three different mRNA species: one in which intron 8 is retained (represented by the 729-bp PCR product), one that lacks 9 bp (the 631-bp product), and one that lacks 13 bp (the 627-bp product) (Fig. 2 C and D). The latter two mRNAs likely arise by means of the activation of cryptic splice sites in the immature clpC2 mRNA. Whereas the mRNA lacking 9 bp can, in principle, give rise to a full-length ClpC2 protein, the other two are predicted to contain premature stop codons that, if translated, would generate truncated proteins lacking the C-terminal nucleotide-binding domain.

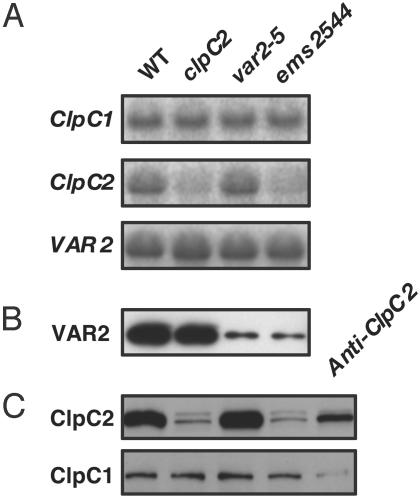

Molecular Analysis of clpC2 Suppression. Perhaps the simplest hypothesis to explain the mechanism of suppression of variegation in ems2544 is a direct interaction between ClpC2 and VAR2, allowing the restoration of near-wild-type VAR2 activities in the double mutants. Experiments described later (see Fig. 4) make this a remote possibility because clpC2 is able to suppress the variegation of null var2 alleles. An alternate hypothesis is that clpC2 exerts its effect in a more indirect manner, perhaps by modifying VAR2 expression or activity. Fig. 3 A and B show that VAR2 mRNA and protein abundances are similar in var2-5 and the double mutants (ems2544), indicating that clpC2 does not impact var2 expression. We have also been unable to detect differences in VAR2 activity in the ems2544 versus var2-5 strains, as monitored by degradation of the 23-kDa cleavage product of the D1 protein after exposure of thylakoids to photoinhibitory illumination conditions (16) (data not shown). This finding suggests that clpC2 does not normalize the activity of the mutant VAR2 protein, at least during the D1 repair cycle. In sum, we conclude that clpC2 does not likely suppress var2-5 variegation by altering VAR2 expression or activity.

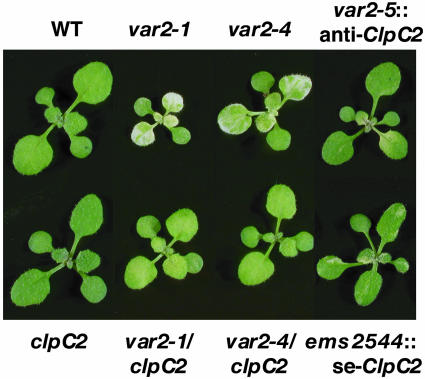

Fig. 4.

Phenotypes of clpC2 single- and double-mutant lines and of overexpression and antisense ClpC2 lines. The clpC2 single mutant was from the F2 of a cross between ems2544 and wild type; it was genotyped by PCR by using derived CAPs markers (supporting information), and the genotype was confirmed by sequencing. Two var2 alleles (var2-1 and var2-4) were crossed with clpC2, and double-mutant progeny (i.e., var2/clpC2) were identified in the F2 by genotyping, as described above for the clpC2 line. Also shown are the antisense ClpC2 transformant in a var2-5 background (var2-5::anti-ClpC2) and a sense ClpC2 transformant in the ems2544 background (ems2544::sense-ClpC2). All of the plants were grown under continuous light (100 microeinsteins per m2·sec-1) for 12 days.

Fig. 3.

Expression of VAR2, ClpC1, and ClpC2. Northern and Western blot analyses with mRNAs or proteins isolated from the wild type (Columbia), the clpC2 line, var2-5, the ems2544 double mutant, or the antisense ClpC2 plants. (A) Northern blot analysis. Equal amounts of total cell RNA (5 μg) from 12-day-old leaves were electrophoresed through 1% Mops-formaldehyde gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The filters were incubated with gene-specific probes for VAR2, ClpC1, and ClpC2. (B and C) Western immunoblot analyses. Intact chloroplasts were prepared from 20-day-old seedlings, and proteins were separated by 12.5% SDS/PAGE. Each lane of the gel contained an amount of protein corresponding to 5 μg of chlorophyll. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and the filters were incubated with antibodies generated to VAR2 (B) or to peptides specific for ClpC1 and ClpC2 (C).

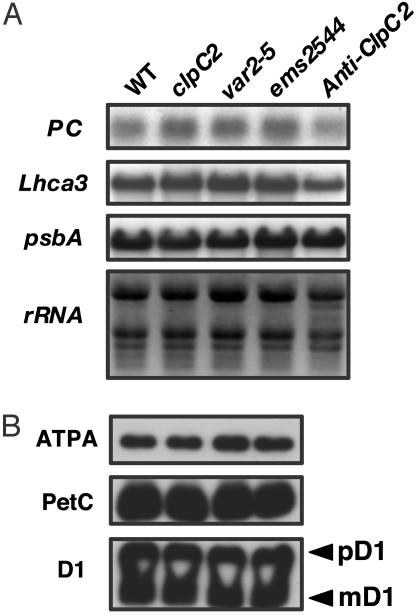

The derived amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis ClpC1 and ClpC2 are very similar (≈82% identity). By using gene-specific probes and antibodies, we found that ClpC2 mRNA and protein levels are markedly reduced in the ems2544 versus var2-5 and wild-type strains (Fig. 3 A and C). It is likely that the ClpC2 proteins arise from the ClpC2 mRNAs that lack 9 bp but in which the reading frame is preserved (Fig. 2C). In contrast to ClpC2, ClpC1 expression is unchanged in the ems2544 plants, which appears to be the case for other photosynthetic proteins as well, inasmuch as the mRNA and protein expression profiles of representative components of the photosynthetic apparatus (plastocyanin, the light harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein of photosystem I, the α-subunit of the ATP synthase, the Rieske FeS protein of the cytochrome b6/f complex, and D1) are similar in the double-mutant, var2-5, and wild-type plants (Fig. 6). The proposal that the composition of the photosynthetic apparatus is not markedly altered by a depletion of ClpC2 has been confirmed by ultrastructural studies showing that the double-mutant plants have wild-type-appearing chloroplasts and by two-dimensional green gel analyses showing that the protein complement of the mutant thylakoid membranes is normal (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Expression of representative photosynthetic proteins. (A) Northern and Western immunoblots were conducted as in Fig. 3. The probes in the Northern blots included the nuclear plastocyanin gene (PC), the nuclear Lhca3 gene (for the light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b binding protein of photosystem I), and the plastid psbA gene (for the D1 protein of photosystem II). rRNA migration is shown as a loading control. (B) The Western blots were incubated with antibodies to the α-subunit of the plastid ATP synthase (ATPA), Rieske FeS protein of the cytochrome b6/f complex (PetC), and D1. The two bands in the D1 lane are the precursor (pD1) and mature (mD1) D1 proteins.

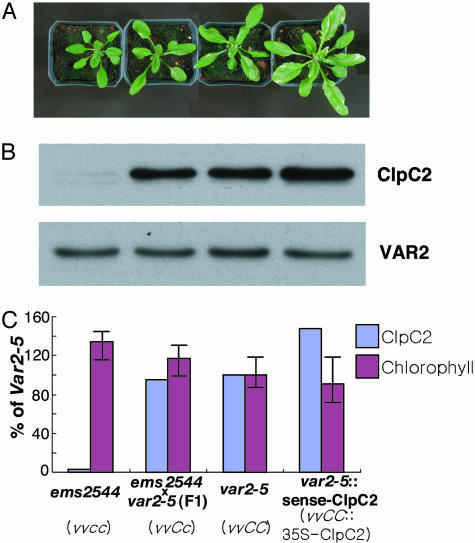

Genetic Interactions Between clpC2 and var2. With respect to wild-type plants, var2-5 plants have accelerated germination and growth rates, and they flower earlier than normal. The ems2544 strain, on the other hand, grows and flowers somewhat more slowly than normal. To examine the phenotype of clpC2 (single mutant) plants, the clpC2 allele was segregated from var2-5 by backcrossing ems2544 with the wild type (Columbia). A clpC2 line was identified in the F2 progeny by using derived CAPS markers (supporting information) to assess the presence or absence of the clpC2 and var2-5 alleles (Fig. 4). These experiments showed that clpc2 is recessive and that the phenotypes of the clpC2 and double-mutant ems2544 plants are the same: These plants are not variegated; they are a darker green than is normal; and they have somewhat lower than normal germination and growth rates. These results indicate that the mutant phenotypes associated with ems2544 are due to a lack of ClpC2 activity, i.e., that clpC2 is epistatic to var2-5.

The Impact of clpC2 Is Not Allele-Specific. To test whether the clpC2-mediated suppression of variegation is specific to the var2-5 allele, the clpC2 line was crossed with other var2 alleles, including var2-1, which contains a nonsense mutation (Q597*), and var2-4, which has a splicing defect (8, 11). Both of these alleles have more severe variegation phenotypes than var2-5. As illustrated in Fig. 4, variegation is suppressed in both of the double mutants, i.e., var2-1/clpC2 and var2-4/clpC2. Growth is also restored to near-normal in the double-mutant strains. Because var2-1 is likely a null allele (11), these data support the earlier hypothesis that suppression of variegation by clpC2 does not occur by means of direct interaction of the VAR2 and ClpC2 proteins

Manipulation of ClpC2 Protein Levels. Titration of ClpC2 in a var2-5 background. To verify that defects in ClpC2 rescue the variegation phenotype of var2-5, a series of transgenic var2-5 plants were generated with variable amounts of the ClpC2 protein (Fig. 5A). All these plants have similar VAR2 protein levels (≈5% of wild type) (Fig. 5B). As discussed earlier (Fig. 3), ClpC2 amounts are sharply reduced in ems2544 (for simplicity, designated vvcc in Fig. 5), but wild-type levels are present in var2-5 (designated vvCC in Fig. 5). Fig. 5B shows that ClpC2 levels are also normal in plants heterozygous for ClpC2 (designated vvCc in Fig. 5), whereas overexpression of ClpC2 in var2-5 by using the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (vvCC::35S-ClpC2) yields plants with higher than normal ClpC2 protein amounts (Fig. 5B). Fig. 5A shows that there is a notable increase in leaf variegation as ClpC2 levels are increased. However, it is difficult to quantify this increase, given that standard deviations of chlorophyll contents tend to be quite high (Fig. 5C) because leaves on a rosette do not display uniform levels of variegation. Fig. 5A further reveals that increases in ClpC2 levels are accompanied by a striking enhancement in plant size. In sum, the data in Fig. 5 are consistent with the proposal that suppression of variegation in ems2544 is due to a mutation in ClpC2 that results in decreased ClpC2 protein accumulation. Further support for this conclusion comes from the observation that overexpression of ClpC2 in the ems2544 strain complements the suppression of variegation in this strain, i.e., the suppressed, nonvariegated plants, which lack ClpC2, become variegated when ClpC2 is added back (Fig. 4). Antisense suppression of ClpC2 in var2-5. Based on the data in Fig. 5, it can be predicted that down-regulation of ClpC2 abundance by expression of ClpC2 antisense RNAs (in a var2-5 background) would give rise to plants (var2-5::anti-ClpC2) that are less variegated than var2-5. In accord with expectations, antisense plants generated to the entire ClpC2 sequence are not variegated (Fig. 4) and they have significantly less ClpC2 protein than var2-5 (Fig. 3C). Yet, in contrast to the suppressed plants in Fig. 5, the young leaves of the antisense plants are initially pale green to yellow, and it is only as development proceeds that the expanding leaves turn green (”yellow-heart” phenotype).

Fig. 5.

Titration of ClpC2 protein content in a var2-5 background. (A) var2-5 plants with various amounts of ClpC2 protein include ems2544, the F1 from a cross between ems2544 and var2-5, var2-5, and overexpression of ClpC2 in var2-5 by using the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. For clarity, the recessive var2-5 and clpC2 genes are designated v and c, respectively, whereas the dominant alleles are designated V and C. The plants were germinated at the same time and maintained under identical conditions for 3 weeks. (B) Protein samples corresponding to equal amounts of chlorophyll (5 μg) were loaded onto 12.5% SDS polyacrylamide gels, and Western immunoblots were conducted by using antibodies to ClpC2 and VAR2. (C) ClpC2 protein amounts on the representative immunoblot in B were quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. Chlorophyll contents were determined on a per-gram, fresh-weight basis on 12 randomly selected, fully expanded fifth leaves from each type of plant. ClpC2 and chlorophyll amounts are shown relative to var2-5 (100%).

The yellow-heart phenotype appears to be due to an inhibition of expression of ClpC1 and ClpC2 because both genes have highly similar nucleic acid sequences (≈80%). ClpC1 and ClpC2 transcripts are decreased in amount in the antisense versus var2-5 plants (data not shown), as are ClpC1 and ClpC2 protein levels (Fig. 3C). Yet the amounts of mRNAs from representative photosynthetic proteins do not appear to be affected in the antisense plants (Fig. 6A). The fact that the antisense plants have a novel phenotype suggests that ClpC1 and ClpC2 act synergistically or that they might be functionally redundant, but only in part. In this context, it might be relevant that the yellow-heart phenotype is reminiscent of mutants blocked in the import of nuclear-encoded proteins into the chloroplast, e.g., ppi1, chaos, or ffc1 (27-30). Because ClpC-type Hsp100 chaperones are associated with the chloroplast import apparatus (31), we speculate that ClpC1 might be involved in import, whereas ClpC2 is not. Alternatively, a threshold of ClpC1 plus ClpC2 might be required for import competence; below this threshold, import is inhibited, generating yellow plastids.

Discussion

ClpC2 Function.The primary function of Hsp100 chaperones, such as ClpC, is to promote the disassembly of aggregated proteins and higher-order protein complexes (23). When complexed with Clp proteolytic subunits, such as ClpP, they unfold substrates and feed them into the catalytic chamber (32). Little is known about the precise physiological roles of ClpC in plants or green algae, although these proteins might play a role in import (31). The same lack of understanding is true for the Clp protease, which is thought to be a housekeeping enyme (4, 13, 33), although expression studies have recently suggested a role in acclimatory responses to various stress conditions (26).

One reason for the dearth of information about the function of ClpC chaperones and Clp proteases is that relatively few Clp mutants have been characterized in photosynthetic eukaryotes. Interestingly, all of these mutants have lesions in the chloroplast DNA-encoded ClpP (proteolytic) subunit of the Clp protease. Analyses of these mutants have revealed that ClpP is necessary for proper chloroplast biogenesis and shoot development (34-36) and for growth and the proteolytic disposal of cytochrome b6/f in the thylakoid membranes of Chlamydomonas (37, 38). Further support for the necessity of ClpP is found in the observation that ClpP is retained and expressed in the degenerated plastid genome of Epifagus (39). However, ClpP might not be necessary in all cell types, e.g., it is not present in nonphotosynthetic maize cell lines (40). Our isolation of a clpC2 mutant thus represents an important advance in the generation of tools to understand the function of Hsp100 chaperones and of the Clp protease in plants. In this paper we found that one function of clpC2 is to suppress the requirement for VAR2 in thylakoid membrane biogenesis.

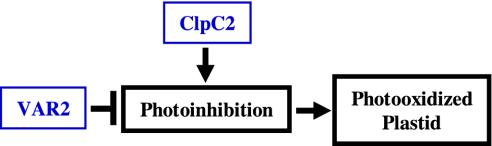

Model of clpC2 Suppression of Defective Chloroplasts. In this study we found that clpC2 is epistatic to var2 and that ClpC2 and VAR2 do not likely interact directly, because suppression of variegation is observed in null alleles of var2. We also found that ClpC2 affects growth in a complex manner (promoting growth of var2-5 and retarding growth of var2-1 and var2-4), perhaps as a secondary consequence of altered thylakoid function. Regardless of the cause, our data are consistent with a working model (Fig. 7) in which ClpC2 acts antagonistically to VAR2, which is involved in photosystem II repair during photoinhibition, likely by degrading the photodamaged D1 protein. We therefore suggest that ClpC2 normally acts to enhance photoinhibition, either directly or indirectly. Consistent with this interpretation, we hypothesize that the chaotic pattern of variegation in var2 plants arises from intrinsic differences in rates of the various reactions, substrate concentrations, and external factors (e.g., light) involved in light capture and use versus the ability of a given plastid to avoid photoinhibition and photodamage. With VAR2 above a threshold, a functional chloroplast would form and turn green; below the threshold, photooxidation would occur and the plastid would turn white. It can further be hypothesized that variegation in var2 is the consequence of the sorting-out of green and white plastid types early in leaf development, when chloroplasts develop from undifferentiated proplastids in the mersistem, then undergo multiple, rapid divisions. This sorting-out process would lead to the generation of mature leaves with green and white sectors containing clones of cells with all-white or all-green plastids.

Fig. 7.

Model of clpC2 suppression of variegation. VAR2 acts to prevent photoinhibition by removing photodamaged D1 proteins. ClpC2 is proposed to promote photoinhibition. When photosystem II repair is not sufficient, photoinhibition can lead to a photodamaged plastid.

According to our working hypothesis, the contribution of ClpC2 to photoinhibition would not be detectable as photodamage in the wild type because endogenous repair/scavenging activities would be sufficient to afford photoprotection. The normal-appearing phenotype of the clpC2 mutant would also be consistent with a lack of the photodamage-promoting activities of ClpC2. Finally, our model predicts that without ClpC2, more plastids would be below the threshold for photooxidation in var2/clpC2 double mutants versus var2 single mutants. If so, the double mutants should be less variegated than the single mutants, which was observed.

We do not know how ClpC2 acts to enhance photodamage, but a number of mechanisms can be envisaged. For instance, ClpC2 could disassemble a thylakoid electron transport complex during the normal maintenance of the photosynthetic apparatus, which might result in enhanced electron pressure upstream in the chain, generating oxygen radicals and photooxidative stress. Alternatively, ClpC2 could act to alter redox poise and the production of oxygen radicals by affecting photosystem stoichiometry, reminiscent of the pmgA mutant of Synechocyctis (41). ClpC2 might exert its effects by acting alone as a chaperone or in concert with ClpP thereby facilitating proteolysis. Although our model is specific for chloroplasts, an expanded role of ClpC2 in other plastid types cannot be ruled out, e.g., as a factor that regulates the assembly of other multimeric complexes in this organelle. Although we do not know the precise mechanism, our working model provides testable hypotheses and an entrance into the poorly understood networks of protein quality control in plastids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to Dr. Lawrence Bogorad, who will be remembered for his infectious enthusiasm, mentoring of numerous students, and seminal contributions to plant science. This research was supported by Energy Biosciences Program Grant DB 230786790 from the Department of Energy (to S.R.R.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: SSLP, simple sequence-length polymorphism; CAPS, cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence.

References

- 1.Baumeister, W., Walz, J., Zühl, F. & Seemüller, E. (1998) Cell 92, 367-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wickner, S. & Maurizi, M. R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8318-8320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam, Z., Adamska, I., Nakabayashi, K., Ostersetzer, O., Haussuhl, K., Manuell, A., Zheng, B., Vallon, O., Rodermel, S. R., Shinozaki, K. & Clarke, A. K. (2001) Plant Physiol. 125, 1912-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adam, Z. & Clarke, A. K. (2002) Trends Plant Sci. 7, 451-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sokolenko, A., Pojidaeva, E., Zinchenko, V., Panichkin, V., Glaser, V. M., Herrmann, R. G. & Shestakov, S. V. (2002) Curr. Genet. 41, 291-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martínez-Zapater, J. M. (1993) J. Hered. 84, 138-140. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, M., Jensen, M. & Rodermel, S. R. (1999) J. Hered. 90, 207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, M., Choi, Y., Voytas, D. F. & Rodermel, S. R. (2000) Plant J. 22, 303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takechi, K., Sodmergen, Murata, M., Motoyoshi, F. & Sakamoto, W. (2000) Plant Cell Physiol. 41, 1334-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakamoto, W., Tamura, T., Hanba-Tomita, Y., Sodmergen & Murata, M. (2002) Genes Cells 7, 769-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu, F., Park, S. & Rodermel, S. R. (2004) Plant J. 37, 864-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakamoto, W., Zaltsman, A., Adam, Z. & Takahashi, Y. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 2843-2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostersetzer, O. & Adam, Z. (1997) Plant Cell 9, 957-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey, S., Thompson, E., Nixon, P. J., Horton, P., Mullineaux, C. W., Robinson, C. & Mann, N. H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2006-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva, P., Thompson, E., Bailey, S., Kruse, O., Mullineaux, C. W., Robinson, C., Mann, N. H. & Nixon, P. J. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 2152-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindahl, M., Spetea, C., Hundal, T., Oppenheim, A. B., Adam, Z. & Andersson, B. (2000) Plant Cell 12, 419-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu, D., Wright, D. A., Wetzel, C., Voytas, D. F. & Rodermel, S. R. (1999) Plant Cell 11, 43-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukowitz, W., Gillmor, C. S. & Scheible, W. R. (2000) Plant Physiol. 123, 795-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell, C. J. & Ecker, J. R. (1994) Genomics 19, 137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jander, G., Norris, S. R., Rounsley, S. D., Bush, D. F., Levin, I. M. & Last, R. L. (2002) Plant Physiol. 129, 440-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aronsson, H. & Jarvis, P. (2002) FEBS Lett. 529, 215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtenthaler, H. K. (1987) Methods Enzymol. 148, 350-382. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schirmer, E. C., Glover, J. R., Singer, M. A. & Lindquist, S. (1996) Trends Biochem. Sci. 21, 289-296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peltier, J. B., Ytterberg, J., Liberles, D. A., Roepstorff, P. & van Wijk, K. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16318-16327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakabayashi, K., Ito, M., Kiosue, T., Shinozaki, K. & Watanabe, A. (1999) Plant Cell Physiol. 40, 504-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng, B., Halperin, T., Hruskova-Heidingsfeldova, O., Adam, Z. & Clarke, A. K. (2002) Physiol. Plantarum 114, 92-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jarvis, P., Chen, L. J., Li, H., Peto, C. A., Fankhauser, C. & Chory, J. (1998) Science 282, 100-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amin, P., Sy, D. A., Pilgrim, M. L., Parry, D. H., Nussaume, L. & Hoffman, N. E. (1999) Plant Physiol. 121, 61-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klimyuk, V. I., Persello-Cartieaux, F., Havaux, M., Contard-David, P., Schuenemann, D., Meiherhoff, K., Gouet, P., Jones, J. D., Hoffman, N. E. & Nussaume, L. (1999) Plant Cell 11, 87-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutensohn, M., Schulz, B., Nicolay, P. & Flugge, U. I. (2000) Plant J. 23, 771-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen, E., Akita, M., Davila-Aponte, J. & Keegstra, K. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 935-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishikawa, T., Beuron, F., Kessel, M., Wickner, S., Maurizi, M. R. & Steven, A. C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 4328-4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shanklin, J., DeWitt, N. D. & Flanagan, J. M. (1995) Plant Cell 7, 1713-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuroda, H. & Maliga, P. (2002) Plant Physiol. 129, 1600-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shikanai, T., Shimizu, K., Ueda, K., Nishimura, Y., Kuroiwa, T. & Hashimoto, T. (2001) Plant Cell Physiol. 42, 264-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuroda, H. & Maliga, P. (2003) Nature 425, 86-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang, C., Wang, S., Chen, L., Lemioux, C., Otis, C., Turmel, M. & Liu, X. Q. (1994) Mol. Gen. Genet. 244, 151-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Majeran, W., Wollman, F.-A. & Vallon, O. (2000) Plant Cell 12, 137-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ems, S. C., Morden, C. W., Dixon, C. K., Wolfe, K. H., de Pamphilis, C. W. & Palmer, J. D. (1995) Plant Mol. Biol. 29, 721-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cahoon, A. B., Cunningham, K. A. & Stern, D. B. (2003) Plant Cell Physiol. 44, 93-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hihara, Y., Sonoike, K. & Ikeuchi, M. (1998) Plant Physiol. 117, 1205-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.