Abstract

White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) have emerged as reservoirs of bovine tuberculosis in northern America. For tuberculosis surveillance of deer, antibody-based assays are particularly attractive because deer are handled only once and immediate processing of the sample is not required. Sera collected sequentially from 25 Mycobacterium bovis-infected and 7 noninfected deer were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), immunoblotting, and multiantigen print immunoassay (MAPIA) for immunoglobulin specific to M. bovis antigens. Various routes of experimental M. bovis infection, such as intratonsillar inoculation (n = 11), aerosol (n = 6), and exposure to infected deer (in contact, n = 8), were studied. Upon infection, specific bands of reactivity at ∼24 to 26 kDa, ∼33 kDa, ∼42 kDa, and ∼75 kDa to M. bovis whole-cell sonicate were detected by immunoblot. Lipoarabinomannan-specific immunoglobulin was detected as early as 36 days postchallenge, and responses were detected for 94% of intratonsillarly and “in-contact”-infected deer. In MAPIA, sera were tested with 12 native and recombinant antigens coated on nitrocellulose. All in-contact-infected (8 of 8) and 10 of 11 intratonsillarly infected deer produced antibody reactive with one or more of the recombinant/native antigens. Responses were boosted by injection of tuberculin for intradermal tuberculin skin testing. Additionally, three of six deer receiving a very low dose of M. bovis via aerosol exposure produced antibody specific to one or more recombinant proteins. M. bovis was isolated from one of three nonresponding aerosol-challenged deer. Of the 12 antigens tested, the most immunodominant protein was MPB83; however, a highly sensitive serodiagnostic test will likely require use of multiple antigens.

White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) are wildlife reservoirs of Mycobacterium bovis infection of cattle (24). An accurate assay for the antemortem detection of M. bovis-infected captive or free-ranging (i.e., after capture) deer would be beneficial for the bovine tuberculosis eradication program within the United States. Traditional tests of M. bovis infection of live cattle rely on cellular immune responsiveness to crude M. bovis antigens. As with cattle, tests of cellular immune reactivity have also proven reliable for detecting tuberculous white-tailed deer (21, 23). One of these tests, the tuberculin skin test, requires handling deer twice, once at the time of antigen administration and again 72 h later for evaluation of the response. Tests requiring a single handling event (e.g., blood-based assays) would minimize risks associated with capture, such as lacerations, fracture, and capture myopathy (to which white-tailed deer are particularly prone). While in vitro cellular based assays appear promising, they require processing of the blood sample within 24 h and are subject to complications associated with overnight delivery (e.g., temperature fluctuations and delays). For these reasons, serological tests of M. bovis infection of white-tailed deer are particularly appealing. However, few studies examining humoral responses of white-tailed deer to M. bovis infection, especially to M. bovis-specific proteins, have been performed (18, 31).

Detection of antibody specific for lipoarabinomannan (LAM)-enriched antigens or highly purified LAM or arabinomannan antigen are useful for diagnosis of mycobacterial infections of cattle and white-tailed deer (5, 9, 10, 17, 25-28, 31, 32). Inclusion of polysaccharide antigens (e.g., LAM or arabinomannan) with protein antigens in multiantigen assays may enhance the overall sensitivity of the test by allowing detection of antibodies directed at both nonproteinaceous as well as proteinaceous epitopes of the mycobacterium (27, 28). Thus, a LAM-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was included in the present study for comparison of responses to specific proteins.

Serologic studies in cattle have shown that the humoral immune response in bovine tuberculosis is generally characterized by recognition of variable patterns of multiple M. bovis antigens of M. bovis (1, 14). In particular, the MPB70 and MPB83 proteins are serodominant antigens in cattle (4, 7, 16). Other specific proteins, such as ESAT-6 and CFP10, can also be recognized by sera from experimentally infected cattle (12, 14). Identification of seroreactive antigens that are specific for M. bovis infection in deer is needed to develop a specific serodiagnostic test.

In the present study, we characterized the kinetics of humoral immunity in white-tailed deer experimentally infected with M. bovis by three different routes. Three immunoassays and a variety of crude and recombinant antigens were used to analyze the antibody responses. The results demonstrated animal-to-animal variation of antigen recognition patterns in infected deer, revealed the immunodominance of MPB83 protein, and suggested that a cocktail of multiple antigens is required for a new serodiagnostic test for tuberculosis in deer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

White-tailed deer, challenge inoculum, bacteriology, and necropsy.

White-tailed deer (1 to 3 years of age) were either raised within a tuberculosis-free herd at the National Animal Disease Center, Ames, Iowa, or obtained from farmed white-tailed deer herds with no history of tuberculosis. Groups consisted of noninfected deer (n = 7) and deer receiving 2 × 108 CFU of M. bovis intratonsillarly (n = 4), 300 CFU of M. bovis intratonsillarly (n = 7), 6 × 102 CFU of M. bovis by aerosol (n = 6) or exposed (in contact) to already infected deer (n = 8). The challenge inoculum (i.e., strain 95-1315, a white-tailed deer isolate) (24) consisted of mid-log-phase M. bovis grown in Middlebrook's 7H9 medium supplemented with 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose complex (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) plus 0.05% Tween 80 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). To harvest tubercle bacilli from the culture media, cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 750 × g, washed twice with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS; 0.01 M, pH 7.2), and diluted to the appropriate cell density. Enumeration of bacilli was by serial dilution plate counting on Middlebrook's 7H11 selective media (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.). Infected deer were housed in pens (two to four deer per pen) inside a biosecurity level 3 building. Intratonsillar, “in-contact,” and aerosol challenge procedures were as described previously (19, 20, 22). For in-contact exposure, noninoculated (i.e., in-contact) deer were moved into the facility housing intratonsillarly challenged deer (i.e., with the deer receiving 2 × 108 CFU of M. bovis 21 days prior). Two in-contact deer were housed with two inoculated deer (120-day cohabitation period) in a pen of approximately 150 ft2. In each pen, deer shared a common source of water and feed. Intratonsillarly inoculated deer were euthanized at 4 (i.e., deer receiving 2 × 108 CFU) or 11 (i.e., deer receiving 300 CFU) months after instillation of M. bovis into their tonsillar crypts. In-contact deer were euthanized 6 months after cohabitation with intratonsillarly inoculated deer. Aerosol-challenged deer were euthanized 5 months after challenge. All deer were euthanized by intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital (Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, Iowa). Various tissues were collected for bacteriologic culture and microscopic examination. Detailed descriptions of cellular immune responses, bacteriologic culture, histopathology, and gross necropsy results are presented elsewhere (18, 20, 22, 29, 30). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols detailing procedures and animal care prior to initiation of the experiments.

CCT.

Prior to the experiment and at 3 and 8 months after inoculation, intratonsillarly inoculated (group receiving 300 CFU) and control deer were tested for in vivo cellular immune reactivity to M. avium purified protein derivative (PPD) and M. bovis PPD (PPDb) by the comparative cervical test (CCT) as described previously (21). In-contact deer were skin tested prior to and 2 months after exposure to intratonsillarly inoculated deer.

ELISA for antibody to LAM-enriched mycobacterial antigen preparations.

Antigens were prepared from M. bovis strain 95-1315, M. avium strain 3988, and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain K10 as described previously (31, 32). Briefly, bacilli harvested from 4-week cultures were sonicated in PBS, further disrupted with 0.1- to 0.15-mm-diameter glass beads (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.) in a bead beater (Biospec Products), centrifuged, filtered (0.22-μm-pore size), and digested in a 1-mg/ml proteinase K (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) solution (50 mM Tris, 1 mM CaCl2 buffer, pH 8.0) for 1 h at 50°C. Protein concentrations were determined (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and antigens were stored at −20°C. The antigen concentrations used for ELISA were 40 μg/ml for M. bovis strain 95-1315 and M. avium strain 3988 and 80 μg/ml for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain K10.

Immulon II 96-well microtiter plates (Dynatech, Chantilly, Va.) were coated with 100-μl/well antigen diluted in carbonate/bicarbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6). Antigen-coated plates, including control wells containing coating buffer alone, were incubated for 15 h at 4°C. Plates were washed three times with 200-μl/well PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (i.e., PBST; Sigma), and blocked with 200-μl/well commercial milk diluent/blocking solution (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.). After incubation for 1 h at 37°C in the blocking solution, wells were washed nine times with 200-μl/well PBST and test sera added to wells (100 μl/well). Test and control sera were diluted 1:100 in PBS containing 0.1% gelatin. Optimal dilutions of test sera were determined by evaluation of the reactivity of twofold serial dilutions ranging from 1:6 to 1:800 (volume of sera/volume of diluent ratio) with each of the antigens (31). After incubation for 20 h at 4°C with diluted test sera, wells were washed nine times with 200-μl/well PBST and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 100-μl/well horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anticervine immunoglobulin G (IgG) heavy and light chains (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories) diluted 1:500 in PBS plus 0.1% gelatin. Wells were washed nine times with 200-μl/well PBST and incubated for 4.5 min at room temperature with 100-μl/well 3,3′ 5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (i.e., substrate; Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories). The reaction was stopped by addition of 100-μl/well 0.18 M sulfuric acid, and the A450 of individual wells was measured with an automated ELISA plate reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, Calif.). The changes in optical density readings (ΔOD) were calculated by subtracting the mean OD readings for wells receiving coating buffer alone (two replicates) from the mean OD readings for antigen-coated wells (two replicates) receiving the same serum sample. The sample/positive (S/P) ratios of test samples were calculated from absorbance values by the formula (sample ΔOD − negative control ΔOD)/(positive sample ΔOD − negative control ΔOD).

Immunoblot assay.

Antibody responses of calves were evaluated over time by immunoblot analysis. Electrophoresis and immunoblot assays were performed by procedures described previously (2) with the following modifications. The antigen for immunoblot was a whole-cell sonicate (WCS) of M. bovis strain 95-1315. Following standard culture, mycobacteria were pelleted (10,000 × g for 20 min) and washed twice with cold PBS. Pellets were resuspended in PBS and sonicated on ice with a probe sonicator. Sonication consisted of three 10-min bursts at 18 W on ice with 10-min chilling periods between sonications. Debris was removed by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 5 min), and supernatants were harvested and stored at −20°C. The protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). Comparisons of the reactivity of serial serum samples against WCS antigen were conducted with a slot-blotting device (Bio-Rad). Antigen was electrophoresed through preparative 12% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. These filters were placed in a blocking solution consisting of PBST and 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (PBST-BSA). After blocking, the filters were placed into the slot blot device and individual sera, diluted 1:200 in PBST-BSA, were added to independent slots. After a 2-h incubation with gentle rocking, blots were washed three with PBST and incubated with HRP-conjugated antigoat IgG heavy and light chains (rabbit origin; Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:20,000 in PBST-BSA for 1.5 h. Blots were again washed three times with PBST and developed for chemiluminescence in SuperSignal detection reagent (Pierce Chemical Co.).

MAPIA.

The following recombinant antigens of M. bovis were purified to near-homogeneity as polyhistidine-tagged proteins (Rv numbers according to the classification of Cole et al. [3] in parentheses): ESAT-6 (Rv3875) and CFP10 (Rv3874) produced at the Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark; MPB59 (Rv1886c), MPB64 (Rv1980c), MPB70 (Rv2875), and MPB83 (Rv2873) produced at the Veterinary Sciences Division, Stormont, Belfast (11); α-crystallin (Acr1 and Rv3391) and the 38-kDa protein (PstS1 and Rv0934) were purchased from Standard Diagnostics, Seoul, South Korea. Polyprotein fusions CFP10/ESAT-6 and Acr1/MPB83 were constructed by overlapping PCR with gene-specific oligonucleotides to amplify the genes from M. tuberculosis H37Rv chromosomal DNA. The fused poly-gene PCR products were cloned into the pMCT6 E. coli expression vector, using SmaI/BamHI restriction enzymes. The polyproteins were purified to near-homogeneity by exploiting the polyhistidine tag encoded by the vector. M. bovis culture filtrate (MBCF) was obtained from a field strain of M. bovis (T/91/1378; Veterinary Sciences Division, Belfast, United Kingdom) cultured in synthetic Sauton's medium. Multiantigen print immunoassay (MAPIA) was performed as described previously (15). Briefly, antigens were immobilized on nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) at a protein concentration of 0.05 mg/ml with a semiautomated airbrush-printing device (Linomat IV; Camag Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, Del.). The membrane was cut perpendicular to the antigen bands into 4-mm-wide strips. Strips were blocked for 1 h with 1% nonfat skimmed milk in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 and then incubated for 1 h with serum samples diluted 1:50 in blocking solution. After washing, strips were incubated overnight with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antideer IgG antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) diluted 1:500, followed by another washing step. Deer antibodies bound to printed antigens were visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP/NTB) (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories).

Statistics.

Data were analyzed by either repeated measures, one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparisons test, or Student's t test with a commercially available statistics program (InStat 2.00; GraphPAD Software, San Diego, Calif.).

RESULTS

Serologic responses to LAM-enriched antigens and WCS.

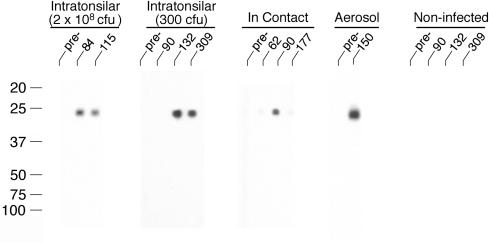

Positive responses (i.e., >0.25 S/P ratio) to M. bovis-derived LAM were detected as early as 36 days postinfection (Fig. 1). Responses to LAM by M. bovis-infected deer were boosted by injection of PPDs for the CCT. Mean (± standard error) ELISA responses by intratonsillarly infected deer increased from 0.55 ± 0.15 (immediately prior to CCT at 3 months postinfection) to 1.027 ± 0.10 1 month after CCT. Injection of PPDs (i.e., 2 months postinfection) also boosted the response by in-contact-infected deer (i.e., from 0.53 ± 0.14 [pre-CCT] to 1.12 ± 0.15 [post-CCT]). Effects of CCT on responses by aerosol-inoculated deer were not evaluated. LAM-enriched antigens derived from M. avium and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis were also recognized by sera from M. bovis-infected deer (Table 1). Twenty-two percent of deer receiving M. bovis either by intratonsillar inoculation or by in-contact exposure had positive responses (i.e., >0.25 S/P ratio) to M. bovis-derived LAM prior to infection, likely indicative of prior exposure to environmental nontuberculous mycobacteria. Upon infection, responses by 94% of these deer (including the four deer with preexisting responses) increased threefold or greater. One control deer had responses ranging from 0.20 to 0.71 to M. bovis-derived LAM over the 309-day period and even greater responses to M. avium- and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis-derived LAM. Another control deer had positive responses (i.e., >0.25 S/P ratio) to each of the three LAM preparations on 3 of the 11 sampling dates. By immunoblot to M. bovis WCS, specific bands of reactivity at ∼24 to 26, ∼33, ∼42, and ∼75 kDa were detected (Fig. 2). Bands were also detected at <20 kDa and ∼100 kDa for in-contact-infected deer.

FIG. 1.

Response kinetics of serum antibody specific for LAM-enriched antigen. Sera from M. bovis-infected deer (i.e., in contact-exposed [*] or intratonsillarly inoculated [□]) and noninfected deer (▪) was analyzed for reactivity to M. bovis-derived LAM by ELISA. The S/P ratios of test samples were calculated from absorbance values by using the formula (sample − negative control)/(positive sample − negative control). Responses >0.25 were considered positive (dashed line). Data are presented as means ± standard error.

TABLE 1.

LAM-enriched antigen derived from various mycobacteria is recognized by sera from M. bovis-infected deer

| Species of origin for antigen preparation | Mean ± SE serum ELISA response (S/P ratio)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noninfected | Intratonsillar

|

In-contact infected | ||

| 300 CFU | 2 × 108 CFU | |||

| M. bovis | 0.18 ± 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.10* | 0.54 ± 0.22 | 0.53 ± 0.14* |

| M. avium | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.84 ± 0.13* | 0.97 ± 0.18* | 0.71 ± 0.17* |

| M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis | 0.19 ± 0.12 | 1.28 ± 0.29* | 0.58 ± 0.50 | 0.79 ± 0.25* |

Shown are mean (± standard error) serum ELISA responses (S/P ratio) from noninfected and M. bovis-infected deer 8 to 9 weeks postchallenge. Asterisks indicate responses by infected deer exceeded (P < 0.05) responses by noninfected deer (horizontal comparisons). Responses to different antigen preparations did not differ (P > 0.05, vertical comparisons).

FIG. 2.

Preparative immunoblots of M. bovis strain 95-1315 WCS antigen probed with sera from white-tailed deer experimentally infected with M. bovis. Molecular mass markers are indicated in the left margin, and days postinfection and treatment groups are indicated in the upper margin. The data presented are representative responses of individual deer from each treatment group.

Serologic responses to specific proteins.

In MAPIA experiments, eight single recombinant antigens, two fusion polyproteins, and two native crude preparations of M. bovis printed on each membrane strip were used. The results of IgG antibody detection are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 2. It was found that 80% of all infected deer (20 of 25) developed humoral responses against MBCF and PPDb. The majority of the responders also produced antibodies to recombinant proteins. The MPB83 antigen was most frequently recognized (64%), followed by MPB70 (48%) and ESAT-6 (40%). Only a few reactors against Acr1, CFP10, MPB59, and MPB64 were found, whereas the 38-kDa protein elicited no antibody response. Fusion Acr1/MPB83 was recognized in serum samples of 72% infected deer. This molecule provided a very strong signal in MAPIA and was reactive as early as 4 weeks postinfection (Fig. 3A). Responses to MPB83 (Fig. 4) and MPB70 (data not shown) were also detected by immunoblot using recombinant antigens. Fusion CFP10/ESAT-6 was positive only in 32% of the infected deer, perhaps due to a relatively lower rate of serological recognition of ESAT-6 and CFP10. There was no antibody against recombinant antigens found by MAPIA in the control group of seven uninfected deer.

FIG. 3.

Antibody responses to recombinant antigens detected by MAPIA in white-tailed deer experimentally infected with M. bovis. (A) animal 348 infected intratonsillarly, (B) animal 280 infected intratonsillarly, (C) animal 294 infected by in-contact exposure, (D) animal 297 infected by in-contact exposure, and (E) animal 548 infected by aerosol. CCT-1 (week 14) and CCT-2 (week 33) show times postinfection when skin tests were performed. The antigens printed are shown on the right. Strips represent different time points during infection when serum samples were collected (shown in weeks in the bottom margin).

TABLE 2.

Rates of antibody responses to protein antigens detected by MAPIA in deer infected with M. bovis by various routes

| Antigen | No. with antigen recognitiona

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intratonsillar (n = 11) | Aerosol (n = 6) | In contact (n = 8) | Total (n = 25) | Sensitivity (%) | |

| MBCFb | 11 | 1 | 8 | 20 | 80 |

| PPDb | 11 | 1 | 8 | 20 | 80 |

| Acr1/MPB83 | 11 | 1 | 6 | 18 | 72 |

| MPB83 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 16 | 64 |

| MPB70 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 48 |

| ESAT-6 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 40 |

| CFP10/ESAT-6 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 32 |

| Acr1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 20 |

| CFP10 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 16 |

| MPB59 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| MPB64 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 38 kDa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Responses are indicative of rates of antigen recognition for each animal measured at various time points postinfection.

FIG. 4.

Preparative immunoblots of recombinant MPB83 probed with sera from white-tailed deer experimentally infected with M. bovis. Molecular mass markers are indicated in the left margin, and days postinfection and treatment groups are indicated in the upper margin.

Antigen recognition patterns generally varied from animal to animal. Figure 3 shows examples of those found in deer infected intratonsillarly (A and B), by in-contact exposure (C and D), or by low-dose aerosol of M. bovis (E). While the immune recognition profiles were heterogeneous in the same group (Fig. 3C and D), similar patterns could be found between animals infected by different routes (Fig. 3B and C or D and E). Thus, serological antigen recognition during experimental tuberculosis in deer does not appear to depend on the route of infection.

In the intratonsillarly infected deer that were skin tested at weeks 14 and 33, antibody responses were apparently boosted by the tuberculin injections. This effect was observed 4 weeks after CCT and was particularly noticeable after the second skin test (Fig. 3A). As a result, the MAPIA bands representing an ongoing antibody response became significantly stronger (ESAT-6, MPB83, both fusion polyproteins). Moreover, in some deer, additional bands appeared only after CCT, showing tuberculin-induced antibodies to Acr1, MPB59, or MPB64. Antibody specific to M. bovis antigens was not found in uninfected deer before or after CCT by MAPIA.

Association between antibody responses and pathology.

In the group of deer infected with a low dose of M. bovis by aerosol, humoral immune responses were compared with pathology and bacteriology data obtained from the same animals postmortem. The results summarized in Table 3 show that three of six infected deer had no gross or microscopic pathology and no bacteriologic findings that would have indicated development of disease. None of the three animals produced antibodies detectable by ELISA or Western blot, and only one deer showed a weak antibody response to ESAT-6 in MAPIA. The other three animals in this group were positive by culture, and one of them developed pathology consistent with tuberculosis. Serum antibodies were detected in these deer by ELISA (one of three), Western blot (three of three), and MAPIA (two of three). Interestingly, the only culture-confirmed animal with pathology (no. 548) had the strongest humoral immune response involving the greatest number of antigens recognized in MAPIA, and it tested positive by all three serologic assays. Relatively poor antibody responses found in the aerosol-infected deer were associated with fewer antigens recognized in this experimental group by MAPIA (Table 2). All 18 animals infected intratonsillarly or by exposure to M. bovis-infected deer had histopathologic evidence of disease and produced variable levels of antibody responses (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of pathology and serology from deer receiving a suboptimal dose of M. bovis by aerosol

| Animal | Pathologya | Antibody assay resultb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAM (ΔS/P ratio) | Immunoblot (kDa) | MAPIA (antigens recognized) | ||

| 536 | —c | −0.17 | — | — |

| 540 | — | −0.09 | — | ESAT-6 |

| 542 | — | −0.03 | — | — |

| 548 | g+, m+, b+ | 0.77 | ∼24-26, ∼33, ∼42, ∼75 | ESAT-6, rMPB83, CFP10/ESAT-6, 16 kDa:MPB83, PPDb, M. bovis CF |

| 550 | b+ | 0.08 | ∼75 | ESAT-6 |

| 568 | b+ | −0.01 | ∼33, ∼75 | — |

Gross (g), microscopic (m), and bacteriologic (b) findings from deer receiving 6 × 102 CFU of M. bovis via aerosol delivery. Serum was collected prior to infection and immediately before euthanasia/necropsy (i.e., 5 months postchallenge).

ELISA responses to LAM are presented as responses at 5 months postchallenge − the response prior to infection (ΔS/P ratio). The response to LAM by deer 548 was considered positive, and responses by other deer were considered negative. Immunoblot data are presented as specific bands of reactivity detected upon infection (i.e., present in postchallenge sera but not in prechallenge sera).

—, negative findings.

DISCUSSION

We characterized the humoral immune response to M. bovis infection in white-tailed deer with emphasis on antigen recognition. Our results demonstrate that irrespective of the route of experimental infection, variable levels of serum IgG antibodies against multiple antigens are produced. The antibodies could be detected by various immunoassays such as ELISA, Western blot, and MAPIA as early as 4 weeks after inoculation of M. bovis. Animal-to-animal variation of antigen recognition patterns was observed in the experiments, thus consistent with our earlier findings in cattle (1, 14) and human tuberculosis (13, 15). The three serologic assays used in the present study provided consistent results, demonstrating increased responses upon injection of PPDs for skin test and similar response kinetics.

Increases in LAM-specific Ig were detected as early as 36 days postchallenge. Responses to LAM prior to infection or during the study in noninfected deer were indicative of exposure to environmental nontuberculous mycobacteria and induction of cross-reactive responses. In a previous study using deer from the same herd, cellular responses to M. bovis BCG vaccination were suggestive of an anamnestic response (33), further evidence of prior exposure to cross-reactive antigens. As with the LAM-based ELISA, nonspecific responses to M. bovis WCS were detected by immunoblot (data not shown). Together, these findings demonstrate the need for highly specific tests (e.g., MAPIA and immunoblot to specific antigens) for the detection of tuberculous deer as it is likely that many captive and free-ranging deer will have exposure to nontuberculous mycobacteria.

In the MAPIA experiments, we screened the largest number of antigens to date and identified several new serological targets recognized in deer tuberculosis. Using 12 antigens that included eight single recombinant proteins and two polyepitope fusions, each consisting of two proteins, we found that all but one recombinant antigen in the panel could detect antibody responses in the infected deer. The most frequently recognized recombinant proteins were MPB83, MPB70, ESAT-6, and both hybrids, each reacting with sera from 32 to 72% of infected deer. Interestingly, the Acr1/MPB83 protein hybrid provided a stronger specific signal in MAPIA than did corresponding single proteins, thus demonstrating the potential of polyepitope fusions in developing a serodiagnostic test for tuberculosis. This phenomenon was previously reported in human and badger studies (6, 8). Several other antigens, Acr1, CFP10, MPB59, and MPB64, showed moderate individual seroreactivity (8 to 20%). No antibody was found against the 38-kDa protein, although it is known to be the most potent serological antigen in human tuberculosis (13). This appears to be in agreement with observations made in tuberculous cattle and badgers (6, 14) suggesting differential expression of the homologous gene by M. bovis versus M. tuberculosis during infection. The MPB70 antigen has been documented as a serodiagnostic reagent for tuberculosis in deer (5). A potential for the other seroreactive antigens reported here, particularly, MPB83, ESAT-6, and CFP10, was previously unknown and and has been demonstrated in deer experiments for the first time.

In the present study, 80% of the experimentally infected animals reacted with M. bovis culture filtrates in MAPIA. Among the recombinant antigens, the most seroreactive was the Acr1/MPB83 fusion that elicited antibody responses in 72% of deer. However, as the animals did not always recognize the same antigen(s), serum antibodies to at least one recombinant protein were detected in 88% of the deer. All antibody nonreactors in the present study were from the group of aerosol-infected deer that received a very low dose of M. bovis and developed little or no detectable pathology. In contrast, all animals infected intratonsillarly or, most importantly, by exposure to tuberculous deer had variable pathology findings and produced antibody responses to multiple antigens. The animal-to-animal variability of antigen recognition by serum antibodies was not dependent on the route of infection, as differential antibody reactivity profiles could be observed in each group while similar antigen recognition patterns in deer from different groups could be also found.

There are certain similarities between cattle (1, 12, 14) and deer humoral responses to M. bovis infection. First, both cattle and deer produced antibodies to multiple antigens with remarkable animal-to-animal variability in antigen recognition patterns. Second, cattle and deer infected with M. bovis reacted to essentially the same set of immunodominant antigens, including MPB83 and MPB70. Third, the humoral responses were strongly boosted shortly after tuberculin skin testing in both host species. In cattle, it has been shown to be mostly associated with anamnestic IgG1 response (11) and to involve a number of antigens that are presumably present in tuberculin (7, 12). Finally, in both animal species, the magnitude of the antibody responses to tuberculosis appeared to be associated with disease progression.

Differences were also observed between antibody responses in cattle and deer. In particular, while cattle experiments revealed marked shifts in antigen predominance during infection in some animals (14), deer in the present study did not show any significant changes of antigen recognition pattern over the course of experimental infection. Further, the onset of antibody responses in cattle infected by exposure to tuberculosis was several months delayed as compared to that in cattle after intranasal infection (14). In contrast, there was no significant difference noted between seroconversion times in groups of deer infected intratonsillarly and by in-contact exposure.

The present study may have several important serodiagnostic implications. First, the development of a serologic immunoassay for deer tuberculosis will require a cocktail of carefully selected antigens to cover a broad spectrum of antibody reactivity. Second, the use of multiepitope hybrids is likely to result in development of improved serologic tests due to superior reactivity of such molecules, especially in membrane-based formats, as compared to single proteins. This approach may lead to a higher signal/noise ratio and thus provide more accurate antibody detection assays. Third, the anamnestic response induced by tuberculin skin tests may be used to further increase the sensitivity of serological assays in detecting infected animals. Additional studies are in progress to determine whether the boosting effect is specific for tuberculosis.

In conclusion, the findings presented above indicate that the antibody production in experimentally infected deer represent a complex part of the immune response to tuberculosis involving variable sets of multiple antigens recognized. The humoral immunity in deer tuberculosis appears to reflect disease-related pathology and may be temporarily affected by the intradermal tuberculin tests. The most prominent serological target identified in the present study is the MPB83 protein, which is also known to be the immunodominant antigen in cattle and badgers (6, 12, 16). However, a highly sensitive serodiagnostic test will require the use of additional seroreactive antigens, particularly polyepitope fusion proteins. Introduction of advanced immunoassay technologies, such as thin-layer immunochromatography, may further improve serologic tests for deer tuberculosis. Such rapid immunoassays that can use whole-blood samples and provide immediate results on site would be an ideal tool for detecting infected animals, especially wildlife and zoo species.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shelly Zimmerman, Peter Lasley, and Janis Hansen for technical support and D. Ewing, J. Kent, J. Lees, K. Lies, A. Lemkuehl, J. Steffen, W. Varland, L. Wright, and T. Wolfe for animal care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amadori, M., K. P. Lyashchenko, M. L. Gennaro, J. M. Pollock, and I. Zerbini. 2002. Use of recombinant proteins in antibody tests for bovine tuberculosis. Vet. Microbiol. 85:379-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannantine, J., and J. R. Stabel. 2000. HspX is present within Mycobacterium paratuberculosis-infected macrophages and is recognized by sera from some infected cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 76:343-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fifis, T., C. Costopoulos, L. A. Corner, and P. R. Wood. 1992. Serological reactivity to Mycobacterium bovis protein antigens in cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 30:343-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaborick, C., M. D. Salman, R. P. Ellis, and J. Triantis. 1996. Evaluation of a five-antigen ELISA for diagnosis of tuberculosis in cattle and Cervidae. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 209:962-966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwald, R., J. Esfandiari, S. Lesellier, R. Houghton, J. Pollock, C. Aagaard, P. Andersen, R. G. Hewinson, M. Chambers, and K. Lyashchenko. 2003. Improved serodetection of Mycobacterium bovis infection in badgers (Meles meles) using multiantigen test formats. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 46:197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harboe, M., H. G. Wiker, J. R. Duncan, M. M. Garcia, T. W. Dukes, B. W. Brooks, C. Turcotte, and S. Nagai. 1990. Protein G-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for anti-MPB70 antibodies in bovine tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:913-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houghton, R. L., M. J. Lodes, D. C. Dillon, L. D. Reynolds, C. H. Day, P. D. McNeill, R. C. Henrickson, Y. A. Skeiky, D. P. Sampaio, R. Badaro, K. P. Lyashchenko, and S. G. Reed. 2002. Use of polyepitope polyproteins in serodiagnosis of active tuberculosis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:883-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jark, U., I. Ringena, B. Franz, G. F. Gerlach, M. Beyerbach, and B. Franz. 1997. Development of an ELISA technique for serodiagnosis of bovine paratuberculosis. Vet. Microbiol. 51:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koets, A. P., V. P. Rutten, M. de Boer, D. Bakker, P. Valentin-Weigand, and W. van Eden. 2001. Differential changes in heat shock protein-, lipoarabinomannan-, and purified protein derivative-specific immunoglobulin G1 and G2 isotype responses during bovine Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 69:1492-1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lightbody, K. A., R. A. Skuce, S. D. Neill, and J. M. Pollock. 1998. Mycobacterial antigen-specific antibody responses in bovine tuberculosis: an ELISA with potential to confirm disease status. Vet. Rec. 142:295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyashchenko, K., A. O. Whelan, R. Greenwald, J. M. Pollock, P. Andersen, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2004. Association of tuberculin-boosted antibody responses with pathology and cell-mediated immunity in cattle vaccinated with Mycobacterium bovis BCG and infected with M. bovis. Infect. Immun. 72:2462-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyashchenko, K. P., R. Colangeli, M. Houde, H. Al Jahdali, D. Menzies, and M. L. Gennaro. 1998. Heterogeneous antibody responses in tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 66:3936-3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyashchenko, K. P., J. M. Pollock, R. Colangeli, and M. L. Gennaro. 1998. Diversity of antigen recognition by serum antibodies in experimental bovine tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 66:5344-5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyashchenko, K. P., M. Singh, R. Colangeli, and M. L. Gennaro. 2000. A multi-antigen print immunoassay for the development of serological diagnosis of infectious diseases. J. Immunol. Methods 242:91-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNair, J., D. M. Corbett, R. M. Girvin, D. P. Mackie, and J. M. Pollock. 2001. Characterization of the early antibody response in bovine tuberculosis: MPB83 is an early target with diagnostic potential. Scand. J. Immunol. 53:365-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, R. A., S. Dissanayake, and T. M. Buchanan. 1983. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using arabinomannan from Mycobacterium smegmatis: a potentially useful screening test for the diagnosis of incubating leprosy. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 32:555-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer, M. V., D. L. Whipple., S. C. Olsen, and R. H. Jacobson. 1999. Cell mediated and humoral immune responses of white-tailed deer experimentally infected with Mycobacterium bovis. Res. Vet. Sci. 68:95-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer, M. V., D. L. Whipple, and S. C. Olsen. 1999. Development of a model of natural infection with Mycobacterium bovis in white-tailed deer. J. Wildl. Dis. 35:450-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer, M. V., D. L. Whipple, and W. R. Waters. 2001. Experimental deer-to-deer transmission of Mycobacterium bovis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62:692-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer, M. V., D. L. Whipple, and W. R. Waters. 2001. Tuberculin skin testing in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 13:530-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer, M. V., W. R. Waters, and D. L. Whipple. 2003. Aerosol exposure of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) to Mycobacterium bovis. J. Wildl. Dis. 39:817-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmer, M. V., W. R. Waters, D. L. Whipple, R. E. Slaughter, and S. L. Jones. 2004. Analysis of interferon-γ production by Mycobacterium bovis infected white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) using an in-vitro based assay. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 16:16-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt, S. M., S. D. Fitzgerald, T. M. Cooley, C. S. Bruning-Fann, L. Sullivan, D. Berry, T. Carlson, R. B. Minnis, J. B. Payeur, and J. Sikarskie. 1997. Bovine tuberculosis in free-ranging white-tailed deer from Michigan. J. Wildl. Dis. 33:749-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugden, E. A., B. S. Samagh, D. R. Bundle, and J. R. Duncan. 1987. Lipoarabinomannan and lipid-free arabinomannan antigens of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 55:762-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugden, E. A., A. H. Corner, B. S. Samagh, B. W. Brooks, C. Turcotte, K. H. Nielsen, R. B. Stewart, and J. R. Duncan. 1989. Serodiagnosis of ovine paratuberculosis, using lipoarabinomannan in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Am. J. Vet. Res. 6:850-854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugden, E. A., K. Stilwell, E. B. Rohonczy, and P. Martineau. 1997. Competitive and indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for Mycobacterium bovis infections based on MPB70 and lipoarabinomannan antigens. Can. J. Vet. Res. 61:8-14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugden, E. A., K. Stilwell, and A. Michaelides. 1997. A comparison of lipoarabinomannan with other antigens used in the absorbed enzyme immunoassays for the serological detection of cattle infected with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 9:413-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waters, W. R., M. V. Palmer, B. A. Pesch, S. C. Olsen, M. J. Wannemuehler, and D. L. Whipple. 2000. MHC class II-restricted, CD4+ T cell proliferative responses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from Mycobacterium bovis-infected white-tailed deer. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 76:215-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waters, W. R., M. V. Palmer, R. E. Sacco, and D. L. Whipple. 2002. Nitric oxide production as an indication of Mycobacterium bovis infection of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J. Wildl. Dis. 38:338-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waters, W. R., M. V. Palmer, and D. L. Whipple. 2002. Mycobacterium bovis-infected white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus): detection of immunoglobulin specific to crude mycobacterial antigens by ELISA. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 14:470-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waters, W. R., J. M. Miller, M. V. Palmer, J. R. Stabel, D. E. Jones, K. A. Koistinen, E. M. Steadham, M. J. Hamilton, W. C. Davis, and J. P. Bannantine. 2003. Early induction of humoral and cellular immune responses during experimental Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection of calves. Infect. Immun. 71:5130-5138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waters, W. R., M. V. Palmer, D. L. Whipple, R. E. Slaughter, and S. L. Jones. 2004. Immune responses of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) to Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination. J. Wildl. Dis. 40:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]