Abstract

Background

Extant studies demonstrate that macro (hierarchical) and micro (relational) governance initiatives in health‐care settings continue to be developed in isolation rather than interactively. Government‐driven hierarchical governance endeavours that guide health‐care reforms and medical practice are disconnected from micro‐level physician–patient interactions being unable to account for patient preferences in the macro‐level policymaking.

Method/Objective

We undertake a review of the recent literature to couch our argument for a unified governance framework for bridging the macro–micro divide in medical contexts. Adopting an interdisciplinary approach to health‐care delivery, we maintain that the (strong) structuration theory provides a fruitful opportunity for narrowing the gap between hierarchical and relational governance.

Discussion

Emphasizing the coexistence of institutional structures and human agency, the (strong) structuration theory elucidates how macro and micro governance devices shape each other's structure via mutually reinforcing cycles of influence. Micro‐level encounters between patients and physicians give rise to social structures that constitute the constraining and enabling forces through which macro‐level health‐care infrastructures are altered and reproduced over time. Permitting to illustrate how patients' agency can effectively emerge from complex networks of clinical trajectories, the advanced structuration framework for macro–micro governance integration avoids the extremes of paternalism and autonomy through a balanced consideration of professional judgement and patient preferences.

Conclusion/Implications

The macro–micro integration of governance efforts is a critical issue in both high‐income states, where medical institutions attempt to deploy substantial realignment efforts, and developing nations, which are lagging behind due to leadership weaknesses and lower levels of governmental investment. A key priority for regulators is the identification of relevant systems to support this holistic governance by providing clinicians with needed resources for focusing on patient advocacy and installing enabling mechanisms for incorporating patients' inputs in health‐care reforms and policymaking.

Keywords: Hierarchical governance, macro–micro integration, patient involvement, relational governance, structuration and strong structuration theories

Introduction

The soaring health‐care costs and their meagre association with clinical outcomes have long been an issue of concern for professionals, scholars and policymakers.1, 2 As medical spending rises at unsustainable rates while patients' levels of satisfaction decline, the pressure to revise the health‐care system became more stringent, leading to additional policy interventions and an intensified scholarly discourse on governance initiatives in health‐care settings.3 Governments are traditionally responsible for designing propitious hierarchical governance infrastructures for drafting nationwide policies, enhancing resource‐allocation efficiency, containing costs, and improving patients' experience with medical services.4 Yet, recent evidence demonstrates that heavily relying on hierarchical governance constitutes a time‐consuming and expensive undertaking, which rarely translates into higher service effectiveness and quality of care.5 In their analysis of ten partnerships in Wales, Entwistle et al.6 found that an overemphasis on hierarchical governance at the expense of efforts that may enhance doctor–patient interactions represents a source of dysfunctionalities in clinical networks. To secure a positive impact on the national health‐care system, governance endeavours require a multifaceted strategy of development along with partnerships among managers, medical personnel and patients.7, 8, 9

According to Bodolica and Spraggon,10 a key challenge of hierarchical governance constitutes its detachment from the micro‐level realities surrounding the physician–patient relationship. While hierarchical governance infrastructures seek to improve the functioning and efficiency of medical institutions, they do not account for patient preferences and other devices for monitoring the encounters between caregivers and receivers. Hierarchical governance refers to macro‐level policy framing and coordination efforts, which occur through administrative top‐down decision making, resource allocation, and controlled planning and implementation.4, 6 Relational governance is associated with micro‐level mechanisms aiming at facilitating interactions via reciprocity, trust, altruism, solidarity, and shared norms that are embedded in patient–physician relationships.11, 12

Although the practice of informed consent represents a step forward allowing patients to express their views during consultations with doctors, extant levels of patient participation in hierarchical governance initiatives remain limited.13 Moreover, despite the current recognition of the importance of patient‐centredness for health system effectiveness, recent literature indicates that this notion is disconnected from policy and regulation, suggesting that enablers should exist at both micro‐ and macro‐levels.9 A stronger involvement of service users in the process of health‐care planning represents an opportunity for enhancing their experience and satisfaction with received care and promoting a culture of openness and mutual learning.14, 15 Observing that hierarchical and relational governance developed in isolation, Bodolica and Spraggon10 advance the need to integrate these macro and micro initiatives into a holistic framework of health‐care governance.

Other researchers15, 16, 17, 18, 19 also concede that effective decision making requires active participation of both professionals and laypeople and that the responsibility for boosting clinical outcomes should be shared among system participants. As patient and community engagement is a critical element in the establishment of an integrated governance of care between the primary and secondary sectors,18 every opportunity should be sought to encourage patients to voice their preferences and get the general public involved in the policy development.20 Ruger16 proposes an integrative agenda of shared health governance which relies on public moral norm (that promotes collective responsibility for building a fair and accessible health‐care system) and ethical commitment of governments, institutions and people to pursue common and individual goods simultaneously rather than advance the interests of powerful stakeholders.

In this article, we undertake a review of the recent literature to continue scholars' journey towards a unified governance framework for bridging the macro–micro divide in medical contexts.10 When promoting higher rates of patient involvement, it is crucial to avoid the narrowly defined consumerist notion of the patient and advocate the moral duty to exert a governance role which stems from broader citizenship values.21, 22 Patients are not mere users–consumers of medical services, they are also citizens of the state, and their collective well‐being may be enhanced if their voices are considered in the system design for the benefit of all parties involved in service exchange.15 Taking an interdisciplinary approach to health‐care delivery, we argue that the theory of (strong) structuration23, 24 provides an opportunity for narrowing the gap between hierarchical and relational governance. Emphasizing the non‐hierarchical duality of institutional structures and human agency, the structuration theory permits accounting for power dynamics in patient–doctor interactions, which are shaped by medical institutions where they take place.25, 26 These interactions give rise to social structures, which constitute the constraining and enabling forces through which hierarchical governance arrangements are altered and reproduced over time (see Box 1).

Box 1. Glossary of structuration theory terms.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Human agency | Human beings' capacity to act freely, behave in an unconstrained way and make independent choices. |

| Structure | Socially induced and created arrangements that limit the availability of choices to make and actions to deploy. |

| Duality | Simultaneous existence of two entities or systems which mutually constitute each other and have no priority over each other. |

| Decoupling | When two units or systems evolve in different directions or separate from each other with no remaining linkage between them. |

| Dialectical relationship | Relating, through opposing forces, two or more systems which cannot exist independently from each other. |

We seek to make a contribution by promoting the macro–micro governance integration in health‐care settings, a critical issue as medical institutions in high‐income and developing countries attempt to deploy substantial realignment efforts, such as lean programmes.7, 27 These programmes empower agents to initiate a system‐related change by providing innovative solutions to problems they face to eliminate inefficient processes and improve their experience. As the structuration theory has been successfully deployed in a variety of disciplines for modelling the incremental readjustment of various spheres of activity,26 it may be applied to medical organizations for bridging the macro–micro governance divide. The advanced structuration framework connects human agency with health‐care institutions, which are composed by individuals' agentic actions that cannot be understood outside the institutional context in which they are embedded. As the framework also permits illustrating how patients' preferences and autonomy can effectively emerge from complex networks of clinical trajectories, regulators are encouraged to install enabling mechanisms for incorporating patients' inputs in health‐care reforms and policymaking.

Literature review

Macro–micro decoupling in health‐care governance

According to Bodolica and Spraggon,10 a persistent decoupling exists between macro and micro governance arrangements in health‐care settings. On the one side, there are hierarchical governance initiatives which include boards of directors, clinical audit and risk management, professional education, peer reviews, and cost–control mechanisms such as pay‐for‐performance, budget and price setting, and evidence‐based practice guidelines.2, 28 These initiatives are enforced by parties which possess legal power and authority, typically the government and medical institutions. Inspired by the principles ensuing from the field of economics, macro‐level governance devices pursue the economic rationality through the application of top‐down business logics to the functioning of health service organizations. The dominant modes of operation and control are directed towards the enforcement of accountability for scarce resource utilization and reduction of costs for boosting clinical performance and securing efficiency of health‐care institutions.

On the other side, there are relational governance attributes for monitoring the relationship between patients and physicians. Grounded in fundamental assumptions of medical ethics, these attributes espouse a patient‐centred approach for safeguarding the quality of interactional micro‐level processes (e.g. consultations). Scholars cluster the mechanisms for overseeing the doctor–patient encounter into trust‐ and distrust‐based governance devices.29, 30, 31 While the former are associated with patients' trust in doctors' standards of morality, domain‐related knowledge, ethical conduct and clinical expertise, the latter are related to patients' autonomy, information empowerment, medical literacy, self‐determination and involvement in decisions affecting personal health. Acknowledging that trust and distrust are bipolar constructs that oscillate between their low and high extremes, Bodolica29 developed a two‐factor theory of relational governance in medical contexts. A ‘high trust–high distrust’ combination is required for an optimal governance of doctor–patient interactions because it permits a simultaneous consideration of physicians' expert authority and patients' decisional autonomy.

The observed macro–micro gap thwarts the incorporation of patients' views into hierarchical governance systems. Although the intention of hierarchical governance is to increase the quality of care, the priority is still given to reducing costs and enhancing operational efficiency. Jha and Epstein5 observe that American hospital boards spend significantly less time on addressing quality‐related issues than their British peers. Several obstacles, including inadequate board experience, prohibitive legal requirements, dearth of resources and deficient performance‐related information, prevent Australian boards from getting more involved in the governance of quality of care.1 According to Walsh,32 the only way for medical institutions to override the ever ballooning costs related to the implementation of governance efforts is by switching the focus from mere cost containment and economic efficiency rationales to the improvement of quality of provided care. Narrowing extant disconnects between hierarchical and relational governance with a proper consideration of power dynamics among actors are required for the enhancement of the health system performance.10, 33

Extant literature indicates that health‐care organizations, which put an extreme emphasis on either hierarchical or relational governance, tend to be inefficient.12 While the macro‐level governance initiatives related to hierarchal coordination mechanisms permit to achieve performance objectives, they do not address the problems of the micro‐level practices which are linked to relational attributes governing the doctor–patient interaction.10 When institutional environments draw heavily on either type of governance, it becomes difficult to secure an effective coordination of efforts deployed at macro‐ and micro‐levels.17 According to Willem and Gemmel,12 situations of predominance of hierarchical governance along with low levels of relational governance are associated with less effective health‐care networks. The integration of hierarchical and relational governance in medical settings may assist in overcoming the potential inadequacies or dysfunctionalities associated with the adoption of pure forms of coordination.6

Many researchers argue that hierarchical and relational governance mechanisms should be seen as complementary rather than substitutes in the establishment of successful health‐care organizations.10, 30, 31 Analysing multiple exchanges in a Belgian medical institute, Berbée et al.34 discovered that governance efforts deployed simultaneously at macro‐ and micro‐levels are mutually strengthening rather than incompatible. Willem and Gemmel12 also found that hierarchical and relational governance complemented rather than substituted each other in a joint attempt to enhance the effectiveness of 19 health‐care networks. As a balanced combination of hierarchy and relational governance is conducive to optimal outcomes, the involvement of all stakeholders in the policymaking represents the critical ingredient for securing the sustainability of medical institutions.17, 35

Dominance of consumerism rather than citizenship

We maintain that the current exclusion of patient voices from hierarchical governance initiatives may be due to the dominance of consumerist notions of the patient rather than citizen. Consumerism emerged as a consequence of rising costs and competition in health‐care markets through the application of economic tools to make the system more responsive to patient needs, give buyers more control over their service purchases, increase transparency, boost professional accountability and secure customer loyalty.21, 36 Patients influence the provided medical services by acting as consumers who are required to make their own judgements about cost and quality, shop around for the best quality–price ratio, and choose the most convenient caregiver for their needs.22, 37 Patient satisfaction became a critical performance indicator of medical institutions that measure clinical outcomes against patient expectations for gaining a larger customer base. Under the pressure of heightened patient–consumer expectations, physicians ought to better position themselves as care providers of choice via positive word‐of‐mouth practices and improved communication flows with their patients.36

Recently, scholars started to warn about the dangers of applying the ‘consumer’ metaphor to the patient, particularly in developing countries where people are more vulnerable and open to abuse. Rowe and Moodley38 note that the emergence of consumerist models in the health service delivery in South Africa leads to the commodification of health care, generating serious ethical challenges and legal implications for the entire system. The authors suggest that the ‘patient–consumer’ trend encourages departure from professional ethics in favour of the ethics of the marketplace and alters the physician–patient relationship, preventing professionals to exert their fiduciary duty and contributing to higher levels of medical lawsuits. Doctors might be encouraged to relax their standards of moral obligation to society and pursue their financial self‐interests, while information‐empowered patients may request inappropriate services or turn to self‐diagnosis and auto‐medication.

The consumerist trend in health care follows the logic of market rationality and a narrowly defined patient choice rather than broader citizenship values. Yet, patients are not merely consumers of care, they are also taxpayers, and as citizens of the state, they have the right to the provision of health services and a say in the way how these services should be administered and deployed.21, 22 According to Wait and Nolte,39 two different perspectives – the consumerist and democratic – underlie today's increasing discourse for public involvement in health policymaking. The consumerist perspective emphasizes the information asymmetry among market participants suggesting that buyers' choice, preferences and satisfaction should be the drivers of health‐care providers' competitiveness. The democratic view highlights not only the right to use public goods but also the duty of people to fulfil their citizenship obligation by enhancing public accountability and contributing to societal well‐being. While consumerism is about patients pursuing their private interests of obtaining the best medical care, citizenship is about individuals' collective responsibility to participate in the management of health services.

Consistent with the democratic perspective, we advocate the active involvement of citizens whose voices regarding health policy goals should be heard by policymakers. There are ‘citizens–taxpayers’ who ought to oversee how medical services are financed, ‘citizens–collective decision‐makers’ concerned with the choice of services, and ‘citizens–patients’ whose preoccupations refer to securing the provision of optimal services to meet public needs.39 People's input could be gathered on priority‐setting decisions in the light of budgetary constraints and health‐care delivery aspects to assist in shaping clinical guidelines. The incorporation of public opinions into hierarchical governance would require going beyond consumers' agency and conceiving patients more holistically as citizens who have both a moral right to self‐determination and a responsibility to the broader society. If public involvement in health care is clearly delineated by investing citizens with proactive rather than reactive roles, we could depart from the top‐down system that governs medical practice towards a more synergistic approach of monitoring at both macro‐ and micro‐levels.

Macro–micro integration and the theory of structuration

An interdisciplinary approach to health‐care governance

Sociologists have long been concerned with how elements at different levels of analysis interact and influence each other, calling for the need of bridging macro and micro domains to place individuals to the front stage and integrate them with social structures.25 Recognizing that social order is built by a plurality of hierarchically positioned actors competing for power and relying on the concepts of emergence and contextualism, researchers have been elucidating the relationship between more or less inclusive phenomena in a cycle of mutual recreation and reproduction.40 The macro–micro linkage came to the forefront of management studies for capturing real‐life events and producing arguments of practical relevance to managers. As social realities are characterized by a complex interplay between lower and higher order phenomena, an inclusive contextualization is required to make sense of these realities.41

Finding that governance scholars have poorly exploited opportunities for blurring the macro and micro spheres despite the influential nature of individual, group and organizational factors, Dalton and Dalton42 highlight the promise of conducting multilevel analyses to better inform practitioners. In a study of board of directors' effectiveness in Norway and Italy, Minichilli et al.43 respond to recent calls of reducing the macro–micro dissociation in the corporate governance arena. The authors found that micro‐level elements (e.g. effort norms, cognitive conflicts and skills' usage) and macro‐level legal and cultural dimensions affect the board task performance and that the national context determines the strength of the relationship between board micro‐processes and performance outcomes.

Due to the interdisciplinary character of health‐care studies, integrative perspectives from different disciplines (e.g. sociology) might be relevant for creating a framework for mutually reinforcing hierarchical and relational governance structures. Acknowledging the multifaceted nature of medical contexts, which incorporate cultural, ethical, political, economic and environmental dimensions, Bem44 posits that social governance should be seen as an essential pillar of health‐care governance. Relying on human kinship as a guiding ethic, social governance is defined as a system which values social equity and a fair access to medical services, encourages a continuous improvement of the human condition, and promotes mutual responsibility for building a healthy society. Social governance allows bringing social theories to the forefront of current debates on health service delivery permitting to lower the inherent tensions between financial and clinical governance.44 We submit that the structuration approach23 (and its refined strong structuration version)24 represents such a social theory that may contribute to the narrowing of the macro–micro gap in health‐care governance.

Tenets of the structuration theory

Giddens23 addresses the debate between two theoretical traditions, which possess competing opinions regarding the supremacy of structure or agency. The structural functionalism approach exhibits a pronounced macro‐level orientation emphasizing the influence of social structure (e.g. norms, institutions) on actors' behaviour. Conversely, the interpretivist perspective draws upon naturalistic methods (e.g. interviews, observations) where meanings are socially constructed by human shared understandings of the reality that surrounds them. Giddens23 integrates key elements from both traditions, positing that structure and agency are not independent but rather symmetrical and mutually constituted in a dialectical relationship where one cannot exist without the other. Structures are produced and reproduced by agents' actions that serve to maintain and modify structures, while these actions are constrained and enabled by those structures.

Human beings are purposive and knowledgeable agents who engage in social activities and unremittingly create and recreate them.23 Agents' actions are seen as a ‘continuous flow of conduct’ rather than isolated behaviours and understood in the context in which they occur. Agency implies power or domination in the allocation of resources and refers to the ‘capacity to make a difference’. Structure is conceived as rules and resources that exist in the mind of agents,45 coerce and support action (i.e. social practices), and are recursively implicated in social reproduction. For Giddens,23 rules are not external formalized prescriptions shaping agents; they occur implicitly in sustained social practices in which agents participate to enact structures. Besides drawing on rules to understand situations or know how to act, agents' actions depend on resources such as allocative ability (i.e. command on objects) or authoritative ability (i.e. command on people).

Strong structuration theory

Refining the work of Giddens,23 Stones24 introduces the strong structuration theory, which allows studying the reciprocal interplay between the micro‐ and macro‐levels while focusing on the centrality of human agency. Stones24 theory draws upon the concept of ‘ontology‐in‐situ’ (i.e. entities and actions exist in their original place of occurrence)46 and considers human agents as linked in dynamic networks of position practices. Position practices refer to the interdependent practices and relations of agents connected within a given context or field.47 The strong structuration theory emphasizes the ‘quadripartite nature of structuration’ which includes the following: ‘external structures’ as conditions of action (i.e. context); ‘internal structures’ which are present in the mind of the agent (i.e. knowledge and schemata to interpret meanings); ‘active agency’ that includes specific practices enacted by agents in a given context; and ‘outcomes’ as the result of human agents' enactments generating variance in external and internal structures. By considering the idiosyncratic combination of events or circumstances, the strong structuration theory seeks to move beyond Giddens23 abstract conceptualizations towards the empirical exploration of the ‘ontology‐in‐situ’ of particular structures and agents.47 Table 1 compares the structuration and strong structuration theories along different dimensions.

Table 1.

Differences between structuration theory and strong structuration theory

| Structuration theory (Giddens23) | Strong structuration theory (Stones24) | |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptualization of structure |

|

|

| Conceptualization of agency |

|

|

| Structure–agency interface |

|

|

| Ontological conceptualization |

|

|

Structuration framework for macro–micro governance integration

Theory of structuration in health‐care settings

As health‐care governance needs to embrace the interrelatedness of hierarchical and relational dimensions, drawing upon the theory of structuration is useful due to the duality and coexistence of institutional structures and human agency. According to Giddens,23 actors' interactions give rise to social structures which constrain and enable human action to reproduce or modify these structures. Relying on the interdependence of micro and macro realms with no a priori sense of hierarchy, primacy and causality, Lawler et al.25 employ the theory of structural social psychology to highlight the importance of micro‐processes for building macro–micro connections. Macro‐level structures provide the venue for individuals to relate to each other giving rise to micro‐level structures that provide the framework for future encounters between individuals, which constitutes the system through which the macro‐structures change over time.

From a structuration point of view, structures are both a medium and outcome of human actions, which they relentlessly organize and modify. The increasing power of patients ensuing from their ability to choose the medical provider and decide their health destiny (i.e. ‘authoritative and allocative abilities’) reinforces their position in physician–patient encounters. This evolving reality results in the creation of micro‐structures of influence, which take the form of new implicit rules of interaction, affecting governance arrangements at the macro‐level. Consistent with the strong structuration theory,47, 48 an important unit of analysis for the macro–micro linkage constitutes the relationship between individuals involved in medical encounters whose actions are shaped by social structures in which they are embedded.

The incorporation of patients' opinions under more constitutive hierarchical governance initiatives should avoid the structure‐relation decoupling and the dominance of one dimension over the other, privileging a continuous alignment and interaction.49 We argue that the attitudes of patients (their ‘internal structures’) are affected by constraining and enabling institutional, organizational and practice‐related forces (‘external structures’), having important implications for the functioning of institutions (‘outcomes’).24 The micro‐level dynamics of doctor–patient relationships influence the activities of health‐care organizations whose features shape the behaviour of actors (their ‘agency’) in medical settings. According to Priem et al.,50 people's understanding of the importance of contextual variables and judgement concerning their causality (agents' ‘internal structures’) can drive the effectiveness of governance endeavours in health‐care institutions. The norms that have been established at the macro‐level for governing social exchange at the micro‐level could be negotiated by participants in an exchange transaction, as doctors and patients are both self‐constructed and constructed by others (e.g. government and professional associations). Patients' interactions with physicians do not only produce meanings and interpretations of each other's roles that are dependent upon social structures in which these interactions occur, but also shape the macro‐level context that surrounds them affecting the dominant norms of the medical profession.47

The strong structuration theory46, 47 allows including in the analysis the human agency related to how people play with power, knowledge and status relations, judgemental processes of individuals, and cognitive determinants of their behaviour. The emergence of alternative governance arrangements that are considerate of patient voices generates more complexity in the professional field, which is mainly ruled by physician discretion and their ‘authoritative and allocative abilities’.23 Drawing upon their ‘internal structures’,47 doctors can make sense of this complexity by reconsidering their roles and adopting, integrating and adjusting these alternatives in the exercise of their clinical practice.51

Patients' information empowerment, autonomy and involvement in decisions concerning their health come to challenge extant norms, authority and power relations in the institutional field. Through repeated interactions with physicians and frequent consultations of health‐related websites, patients are socialized into their new roles and instructed to the medical practice affecting its pre‐established characteristics.52 This modification of patients' role could drive the reconstruction in clinicians' role identity by opening opportunities for shared decision making and joint responsibility for outcomes. From a structuration standpoint, the macro–micro integration may thus occur as the alteration of patient and physician roles at the micro‐level could gradually be diffused at larger organizational and professional levels modifying the dominant macro‐structures governing the clinical profession.

Hasselbladh and Bejerot53 show that health‐care governance in Sweden is steadily moving towards the promotion of the capacity of individual patients and collective patient interest groups to exercise self‐monitoring rather than depend exclusively on clinicians' knowledge and expertise. Considering the new ways of relationship construction in medical markets, Swedish government seeks to motivate the patient to act knowledgeably and responsibly. As participants at different levels engage in newly created avenues for exchange and action upon medical products, they interact and adapt to each other developing new roles and producing new knowledge. The evolving realities with new actors and flows of communication necessitate reframing of medical practice along with the generation of new modes of evaluation and systems of control.54 The transformation of health‐care governance should not emphasize the separate responsibility of institutions, groups or individuals but rather focus on their interrelatedness and shared monitoring responsibility.8, 9, 54

The structuration‐induced interdependence among actors in medical settings determines an increased inclusion of patients' demands and concerns, changing the boundaries of physicians' work and the nature of health‐care system.49 Under the condition of growing interiorization of control by patients–citizens, the overseeing of clinical acting and policymaking ought to evolve from the intraprofessional field to multiple arenas and interlevel coordination.47 According to Hasselbladh and Bejerot,53 the medical profession itself has contributed to the rupture of its monopoly over the ultimate clinical decision making by integrating new priorities and new forms of expertise. As patients assume more ownership of their health problems, their subjective input ought to be taken into consideration in hierarchical governance initiatives to improve and rationalize the system of health service delivery.55 Over time, patients who take control of their health destiny could boost the effectiveness of macro‐level structures by reducing health‐care costs.

Potential tensions from macro–micro integration

The proposed macro–micro governance integration may not be without tensions. Many studies discuss the important role of both doctors' support in achieving successful outcomes in the delivery of care and their resistance to changes that might affect their professional independence.56, 57 Some researchers document how physicians manoeuvre through governmental initiatives, taking advantage of emerging opportunities to fulfil personal interests and failing to act in their patients' best interest.58, 59 James et al.60 found that doctors' private links with pharmacies generate perverse financial incentives to overprescribe or prescribe high‐profit margin products and induce patients to consume in their pharmacies. The provision of care is increasingly subjected to market rationality where the partitioning of resources occurs in the light of economic principles of profit and efficiency rather than physicians' autonomy. The ‘external structures’ represented by professional norms may be perceived by clinicians as containing their behaviour and discretion.61 As governments impose resource limitations to make the health‐care system more effective,3 physicians may reveal their discontent with governmental pressures that reduce their control over medical acting. Ginsburg et al.56 showed that doctors do not simply change their behaviour but actually oppose the new institutional expectations when they are perceived as tools for restraining their freedom and challenging their sense of identity.

The advocated integration of health‐care governance could create similar disturbances in the medical practice, as clinicians might feel threatened in their professional autonomy if patients become too involved.62 Several scholars argue that the policy of patients' choice denies their vulnerability, reasoning limitations and dependence upon clinicians' expertise, inducing patients to develop cognitive illusions, megalomaniac phantasies and power misapprehensions.63, 64 Neglecting the dependency–inadequacy duality, this policy emphasizes the economic thinking which overrides any sense of social obligation and citizenship, damages public trust in health‐care institutions and alters the balance of power in doctor–patient encounters.55, 65

Adopting a psychological approach, Reach66 posits that the exercise of autonomy is put in jeopardy by factors which affect the therapeutic decisions of patients, such as their mental states, emotional predispositions, division of mind, present‐ versus future‐oriented preferences, ignorance and weakness of will. According to Boivin et al.,54 the concealed dynamics that govern the relationships between patients and physicians ought to be considered in the process of critical deconstruction of the policy of patient choice and its effective implementation. Although patient autonomy could be perceived as an attempt to curb professionals' power in diagnosing and prescribing treatment, the multifaceted nature of health‐care issues requires a vigorous participation of all stakeholders for securing superior outcomes.55, 62 Indirect modes of control are more expensive, and patient involvement initiatives are part of making the overseeing of clinical policy and practice more direct.54

Physicians will be brought to adjust their individual reactions to changing circumstances by reconsidering the importance of their exclusive access to medical knowledge and the centrality of autonomy to their professional identity. Consistent with the idea of associating clinical and market discourses,12 doctors' subjectivity needs to be shaped towards new interpretations of evolving realities and patient‐inclusive behaviour.67, 68 There is a growing recognition of the importance of patient participation and family involvement as critical elements of effective medical service delivery that accounts for individuals' needs, values, preferences and family circumstances.35, 69 Person‐ and family‐centred care is gaining prominence among health‐care providers as it constitutes an innovative approach that engages patients and their families and promotes choice and well‐being.49

This holistic approach emphasizes the significant benefits of involving multiple stakeholders for patients, caregivers and service providers.49 Analysing four cases of patients, Laurance et al.69 show that a closer collaboration among patients, families, medical professionals, health‐care systems and policymakers can help nations offer more efficient and population‐suitable care. According to Feinberg,35 person‐ and family‐centred care contributes to the transformation of health care positioning the person and family at the core of the care team and incentivizing clinical and social professionals to act synchronously with shared responsibility for patient care rather than as autonomous providers with sole responsibility. This initiative focuses on both treatment and prevention rather than exclusively on treatment, relies on best practice guidelines as principles that define medical practice rather than standards that constrain doctors' behaviour, and adopts a holistic rather than partial view of patients' and their health issues.70, 71

The accessibility of medical knowledge to lay patients dilutes the traditional medical culture, questioning the physician–patient power relations and altering factors that govern the subjectivity of actors.72 In the pursuit of their daily objectives, clinicians start regulating their activities to gradually align with practices that are considerate of patients' needs for self‐determination.35 By reacting to demands placed on them by patients, doctors act upon their autonomy redefining the frames of their professional roles in the light of their subjectivity. As participants in the newly created realities of empowered patients, physicians open to new meanings and interpretations of their roles, which do not require only technical knowledge but also skills to communicate with patients and take their preferences into account.71

In an empirical study of two drug clinics in Finland, Leppo and Perala73 show that policies of patient choice do not lead to the erosion of doctors' clinical power but rather to the emergence of new forms of expertise and changing modes of professionalism. Yet, from a structuration viewpoint, the evolution of organizational realities and professional identity occurs as part of the broader institutional and social context where new and old tensions are incorporated and coexist.47 As the enactment of patient preference and agency is dependent upon the contextual specificities and complex power relations, our argument for integrative forms of governance is couched by the (strong) structuration theory,23, 24 which sheds light on the micro‐foundations of macro‐level patterns in health‐care settings.

Conclusion

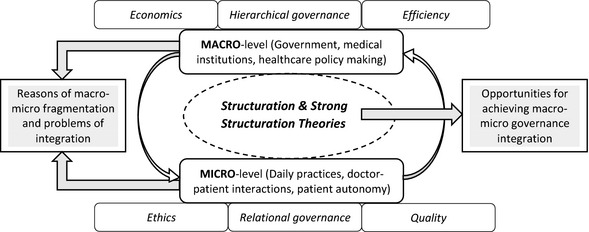

The macro‐level institutional norms that guide clinical practice and micro‐level patterns of behaviour and cognition that shape the reality surrounding the physician–patient encounter have developed separately rather than interactively.10 As the fragmentation of hierarchal and relational governance persists,6 we advocate the integration of these dialectically related domains through the involvement of patients and community in health‐care decisions and priority setting.72 This article discusses the consumerist reasons of the current exclusion of patient voices from hierarchical governance initiatives and elaborates on the moral duty of patients–citizens to get involved in medical policymaking. Relying on the (strong) structuration theory which uncovers how macro‐ and micro‐level devices shape each other's structure via mutually reinforcing cycles of influence, we argue that health‐care organizations would benefit from the incorporation of interactional processes under institutional infrastructures which provide the foundation for these interactions.23, 24 Adopting a structuration approach to pursue the macro–micro integration (see Fig. 1) allows avoiding the extremes of paternalism and autonomy and balancing clinicians' professional judgement and patients' preferences.

Figure 1.

Macro–micro health‐care governance integration through the structuration and strong structuration theories.

It is not sufficient to have in place macro governance systems for controlling clinical effectiveness because the achievement of optimal outcomes hinges upon doctors' understanding of these systems, perception of their roles in implementing them, and patients' increasing tendencies for self‐determination.49 Consistent with Malone's74 recommendations for modern corporations, balancing ‘top‐down control with bottom‐up empowerment’ should be the main emphasis of the advocated linkage between hierarchical and relational governance in health‐care contexts. The patient has to become the centre for organizing the relationship with the physician and for delineating new procedures of internal control and monitoring of the clinical practice.35, 71 The priority for policymakers should be the identification of systems that would support this holistic health‐care governance by providing medical professionals with needed resources for focusing on patient advocacy and participation.

The macro–micro governance integration may induce positive consequences at both macro‐ (e.g. strengthening of the whole health‐care system) and micro‐levels (i.e. heightening of patients' rates of engagement and satisfaction). Patients are users of medical services, and they are more likely to be satisfied with provided care when they get more involved in health‐related decisions, such as resource distribution and service offerings.10, 22 The proposed structuration‐based framework highlights the ability for macro‐level infrastructures to be reproduced in on‐going social actions initiated by clinicians and patients. Despite a rising recognition that clinicians can develop viable strategies for reinforcing the sustainability of medical systems, policymakers still ought to acknowledge that health‐care reforms can be effectively driven by patients and install enabling mechanisms for channelling their contribution towards productive macro‐level outcomes.

The advocated integration of macro and micro governance endeavours is relevant for policymaking in both wealthy nations and low‐income countries. While in the former nations systemic improvements and the consideration of patient preferences in the delivery of care remain at the forefront of legislators' agenda,9 governance initiatives in the latter states are lagging behind due to leadership weaknesses and lower levels of governmental investment.8 Yet, high levels of flexibility and adaptability should be advocated in the deployment of efforts for bridging the macro–micro gap in health‐care governance.18 As medical systems in developed and developing nations face different economic, legal and cultural realities, citizens–patients of these countries may be more or less prepared for enhancing their involvement in health‐related policies and decisions.38 Integration initiatives should be flexible enough to occur at various levels of intensity depending on the particular national context in which they take place.

References

- 1. Bismark MM, Studdert DM. Governance of quality of care: a qualitative study of health service boards in Victoria, Australia. BMJ Quality & Safety, 2014; 23: 474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stabile M, Thomson S, Allin S et al Health care cost containment strategies used in four other high‐income countries hold lessons for the United States. Health Affairs, 2013; 32: 643–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sorensen R, Paull G, Magann L, Davis J. Managing between the agendas: implementing health care reform policy in an acute care hospital. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 2013; 27: 698–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barbazza E, Tello JE. A review of health governance: definitions, dimensions and tools to govern. Health Policy, 2014; 116: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jha AK, Epstein AM. A survey of board chairs of English hospitals shows greater attention to quality of care than among their US counterparts. Health Affairs, 2013; 32: 677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Entwistle T, Bristow G, Hines F, Donaldson S, Martin S. The dysfunctions of markets, hierarchies and networks in the meta‐governance of partnership. Urban Studies, 2007; 44: 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burkoski V, Yoon J. Continuous quality improvement: a shared governance model that maximizes agent‐specific knowledge. Nursing Leadership, 2013; 26: 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abimbola S, Negin J, Jan S, Martiniuk A. Towards people‐centered health systems: a multi‐level framework for analyzing primary health care governance in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Health Policy and Planning, 2014; 29: 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scholl I, Zill JM, Harter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient‐centeredness – a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS ONE, 2014; 9: e107828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bodolica V, Spraggon M. Clinical governance infrastructures and relational mechanisms of control in healthcare organizations. Journal of Health Management, 2014; 16: 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson G. Between Hierarchies and Markets: the Logic and Limits of Network Forms of Organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Willem A, Gemmel P. Do governance choices matter in health care networks? An exploratory configuration study of health care networks. BMC Health Services Research, 2013; 13: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rao AC. Patient involvement in clinical governance. The Nursing Journal of India, 2011; 2011: 225–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaini BK. Healthcare governance for accountability and transparency. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council, 2013; 11: 109–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferrer AP, Brentani AV, Sucupira AC, Navega AC, Cerqueira ES, Grisi SJ. The effects of a people‐centred model on longitudinality of care and utilization pattern of healthcare services—Brazilian evidence. Health Policy and Planning, 2014; 29: 107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ruger JP. Shared health governance. American Journal of Bioethics, 2011; 11: 32–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McInnes E, Middleton S, Gardner G et al A qualitative study of stakeholder views of the conditions for and outcomes of successful clinical networks. BMC Health Service Research, 2012; 12: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nicholson C, Jackson C, Marley J. A governance model for integrated primary/secondary care for the health‐reforming first world – results of a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 2013; 13: 528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shortell SM, McClellann SR, Ramsay PP, Casalino LP, Ryan AM, Copeland KR. Physician practice participation in accountable care organizations: the emergence of the Unicorn. Health Services Research, 2014; 49: 1519–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ovretveit J, Hansson J, Brommels M. An integrated health and social care organization in Sweden: creation and structure of a unique local public health and social care system. Health Policy, 2010; 97: 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mold A. Patient groups and the construction of the patient‐consumer in Britain: an historical overview. Journal of Social Policy, 2010; 39: 505–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tritter JQ. Revolution or evolution: the challenges of conceptualizing patient and public involvement in a consumerist world. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Giddens A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stones R. Structuration Theory. Basingstoke: Palgrave‐Macmillan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lawler EJ, Ridgeway C, Markovsky B. Structural social psychology and the micro‐macro problem. Sociological Theory, 1993; 11: 268–290. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gray B, Purdy J, Ansari S. From interactions to institutions: microprocesses of framing and mechanisms for the structuring of institutional fields. Academy of Management Review, 2015; 40: 115–143. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Al‐Balushi S, Sohal AS, Singh PJ, Al Hajri A, Al Farsi YM, Al Abri R. Readiness factors for lean implementation in healthcare settings – a literature review. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 2014; 28: 135–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Phillips CB, Pearce CM, Hall S et al Can clinical governance deliver quality improvement in Australian general practice and primary care? A systematic review of the evidence. Medical Journal of Australia, 2010; 193: 602–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bodolica V. Extending the two‐factor theory to healthcare contexts: trust‐ and distrust‐based governance configurations in patient‐doctor encounters. Academy of Taiwan Business Management Review, 2013; 9: 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tofan G, Bodolica V, Spraggon M. Governance mechanisms in the physician‐patient relationship: a literature review and conceptual framework. Health Expectations, 2013; 16: 14–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tofan G, Spraggon M, Bodolica V. Agency problems, ethical challenges and governance attributes in different models of physician–patient interaction within the assisted reproduction setting. Public Health, 2013; 127: 597–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walsh K. Clinical governance: costs and benefits. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2014; 2: 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brinkerhoff DW, Bossert TJ. Health governance: principal‐agent linkages and health system strengthening. Health Policy Planning, 2014; 29: 685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berbée R, Gemmel P, Droesbeke B, Casteleyn H, Vandaele D. Evaluation of hospital service level agreements. International Journal of Healthcare Quality Assurance, 2009; 22: 483–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Feinberg LF. Moving toward person‐ and family‐centered care. Public Policy Aging Report, 2014; 24: 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bretton H. The advent of the consumer‐patient. Health Care Strategies Manager, 2006; 24: 12–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thompson M, Cutler CM. Health care consumerism movement takes a step forward. Benefits Quarterly, 2010; 26: 24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rowe K, Moodley K. Patients as consumers of health care in South Africa: the ethical and legal implications. BMC Medical Ethics, 2013; 14: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wait S, Nolte E. Public involvement policies in health: exploring their conceptual basis. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 2006; 1: 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Haynor AL. Micro‐macro integration in sociology: whither progress? Sociological Forum, 1989; 4: 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bamberger P. Beyond contextualization: using context theories to narrow the micro‐macro gap in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 2008; 57: 839–846. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dalton DR, Dalton CM. Integration of micro and macro studies in governance research: CEO duality, board composition and financial performance. Journal of Management, 2011; 37: 404–411. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Minichilli A, Zattoni A, Nielsen S, Huse M. Board task performance: an exploration of micro‐ and macro‐level determinants of board effectiveness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2012; 33: 193–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bem C. Social governance: a necessary third pillar of healthcare governance. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2010; 103: 475–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jones MR, Karsten H. Giddens's structuration theory and information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 2008; 32: 127–157. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jack L, Kholeif A. Introducing strong structuration theory for information qualitative case studies in organization, management and accounting research. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 2007; 2: 208–225. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Greenhalgh T, Stones R. Theorizing big IT programs in healthcare: strong structuration theory meets actor‐network theory. Social Science and Medicine, 2010; 70: 1285–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schwandt DR, Szabla DB. Structuration theories and complex adaptive social systems: inroads to describing human interaction dynamics. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 2013; 15: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barnsteiner J, Disch J, Walton M. Person and Family Centered Care. Indianapolis: Sigma Theta Tau International, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Priem RL, Walters BA, Li S. Decisions, decisions! How judgment policy studies can integrate macro and micro domains in management research. Journal of Management, 2011; 37: 553–580. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chreim S, Williams BE, Hinings CR. Interlevel influences on the reconstruction of professional role identity. Academy of Management Journal, 2007; 50: 1515–1539. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nicolini D. Practice as the site of knowing: insights from the field of telemedicine. Organization Science, 2011; 22: 602–620. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hasselbladh H, Bejerot E. Webs of knowledge and circuits of communication: constructing rationalized agency in Swedish health care. Organization, 2007; 14: 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boivin A, Lehoux P, Burgers J, Grol R. What are the key ingredients for effective public involvement in health care improvement and policy decisions? A randomized trial process evaluation. Milbank Quarterly, 2014; 2014: 319–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fotaki M. Can consumer choice replace trust in the National Health Service in England? Towards developing an affective psychosocial conception of trust in health care. Sociology of Health & Illness, 2014; 36: 1276–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ginsburg S, Bernabeo E, Holmboe E. Doing what might be “wrong”: understanding internists' responses to professional challenges. Academic Medicine, 2014; 89: 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sacks DW. Physician agency, compliance, and patient welfare: evidence from anti‐cholesterol drugs. Job Market Paper, 2014. Available at http://kelley.iu.edu/BEPP/documents/sacks%20paper_2.pdf, accessed 17 January 2015.

- 58. Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. Do physicians' financial incentives affect medical treatment and patient health? American Economic Review, 2014; 104: 1320–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Engelberg J, Parsons C, Tefft N. First, do no harm: financial conflicts in medicine. 2013. Working Paper Available at: http://www.usc.edu/schools/business/FBE/seminars/papers/F_11-14-13_ENGELBERG.pdf, accessed 14 December 2014.

- 60. James CD, Peabody J, Solon O, Quimbo S, Hanson K. An unhealthy public‐private tension: pharmacy ownership, prescribing, and spending in the Philippines. Health Affairs, 2009; 28: 1022–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kesternich I, Schumacher H, Winter J. Professional norms and physician behavior: homo oeconomicus or homo hippocraticus? Discussion Paper, 2014; SFB/TR 15, No. 456. Available at http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-epub-18991-8, accessed 5 February 2015.

- 62. Williamson L. Patient and citizen participation in health: the need for improved ethical support. American Journal of Bioethics, 2014; 14: 4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fotaki M. Choice is yours: a psychodynamic exploration of health policymaking and its consequences for the English National Health Service. Human Relations, 2006; 59: 1711–1744. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Trout JD. Forced to be right. Journal of Medical Ethics, 2014; 40: 303–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tritter JQ, Lutfey K, McKinlay J. What are tests for? The implications of stuttering steps along the US patient pathway. Social Science & Medicine, 2014; 107: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Reach G. Patient autonomy in chronic care: solving a paradox. Patient Preference and Adherence, 2014; 8: 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, Burgers J, Grol R. Involving patients in setting priorities for healthcare improvement: a cluster randomized trial. Implementation Science, 2014; 9: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Nguyen F, Moumjid N, Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T, Carrère MO. Treatment decision‐making in the medical encounter: comparing the attitudes of French surgeons and their patients in breast cancer care. Patient Education and Counseling, 2014; 94: 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Laurance J, Henderson S, Howitt PJ et al Patient engagement: four case studies that highlight the potential for improved health outcomes and reduced costs. Health Affairs, 2014; 33: 1627–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jones JE, Kessler‐Jones A, Thompson MK, Young K, Anderson AJ, Strand DM. Zoning in on parents' needs: understanding parents' perspectives in order to provide person‐centered care. Epilepsy & Behavior, 2014; 37: 191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lindberg J, Kreuter M, Persson LO, Taft C. Family members' perspectives on patient participation in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. International Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 2014; 2: 223. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Baathe F, Ahlborg JG, Lagström A, Edgren L, Nilsson K. Physician experiences of patient‐centered and team‐based ward rounding – an interview based case‐study. Journal of Hospital Administration, 2014; 3: 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Leppo A, Perala R. User involvement in Finland: the hybrid of control and emancipation. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 2009; 23: 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Malone TW. Is empowerment just a fad? Control, decision‐making, and IT. Sloan Management Review, 1997; 38: 23–35. [Google Scholar]