Abstract

Newborn infants have a higher susceptibility to various pathogens due to developmental defects in their host defense system, including deficient natural killer (NK) cell function. In this study, the effects of interleukin-15 (IL-15) on neonatal NK cells was examined for up to 12 weeks in culture. The cytotoxicity of fresh neonatal mononuclear cells (MNC) as assayed by K562 cell killing is initially much less than that of adult MNC but increases more than eightfold after 2 weeks of culture with IL-15 to a level equivalent to that of adult cells. This high level of cytotoxicity was maintained for up to 12 weeks. In antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) assays using CEM cells coated with human immunodeficiency virus gp120 antigen, IL-15 greatly increased ADCC lysis by MNC from cord blood. IL-15 increased expression of the CD16+ CD56+ NK markers of cord MNC fivefold after 5 weeks of incubation. Cultures of neonatal MNC with IL-15 for up to 10 weeks resulted in a unique population of CD3− CD8+ CD56+ cells (more than 60%), which are not present in fresh cord MNC. These results show that IL-15 can stimulate neonatal NK cells and sustain their function for several weeks, which has implications for the clinical use of IL-15.

Natural killer (NK) cells are large granular lymphocytes capable of lysing certain tumor and virus-infected cells without major histocompatibility restriction (5, 6, 12-14, 33, 48). NK cells are defined as membrane CD3−, CD56+ lymphoid cells (3, 4) that also express the FcRIII receptor (CD16) responsible for killing antibody-coated target cells (24, 25). Several defects have been identified in NK cells of newborn infants that may make them more susceptible to viral infection than adults. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), mediated by NK cells, is lower in newborn mononuclear cells (MNC) than in adults (27, 28, 30). MNC from newborn infants have reduced capacity to produce cytokines, particularly interleukin-2 (IL-2) and gamma interferon (12, 14, 30, 31), both of which are important in upregulating NK cytotoxicity, which further contributes to the newborn's susceptibility to infection (32, 34, 35).

Cytokines, such as IL-2, increase the cytotoxicity of neonatal NK cells against K562 targets (36, 37, 41) and virus-infected cells (42). IL-12, a 75-kDa heterodimeric cytokine secreted by monocytes and neutrophils, has been shown to enhance cytotoxicity against K562 and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected cells by both healthy adult and neonatal NK cells, although it is less effective in neonatal cells (7, 23, 44, 45). IL-12 acts synergistically with IL-2 to induce lymphokine-activated cytotoxicity in fresh NK cells from healthy adult controls (10).

A recently cloned cytokine, IL-15, distinct from IL-2 and IL-12, has been found to play an important role in enhancing various lymphocyte functions, including NK and T-cell cytotoxicity (7, 10, 19, 53). IL-15 is a 14- to 15-kDa cytokine first identified in the culture supernatants from two simian cell lines and produced primarily by monocytes or macrophages in humans (11, 17). Transfection studies demonstrate that IL-15 interacts with the β and γc subunits of the IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) complex necessary for binding and signal transduction (20). IL-15 requires the IL-2R β chain, but not the α chain, to induce lymphocyte activity, making it the only cytokine other than IL-2 that employs the β subunit (10, 23). IL-15R uses a unique α chain and has a broader tissue distribution than IL-2R, as the expression of IL-15 mRNA has been detected in the placenta, skeletal muscle, kidney, and activated monocytes/macrophages (2, 21, 23). IL-2 and IL-15 are members of the four-α-helix bundle cytokine family and, thus, share biological functions, which include stimulating T-cell proliferation, inducing activation of NK cells, and stimulating immunoglobulin production by B cells (7). IL-15 stimulates the production of other cytokines by NK cells, including gamma interferon, granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (10). IL-15 is similar to IL-2 in its ability to act synergistically with IL-12 to enhance NK activity (10). IL-15, as well as IL-2, increases the ability of NK cells to mediate ADCC (10), stimulates the expansion of AIDS virus-specific cytotoxic T-cell lymphocytes in HIV-infected patients (29), activates NK cell adhesion to the vascular endothelium, and activates the migratory response (1). IL-15 differs from IL-2 in its ability to stimulate mast cell proliferation and skeletal muscle hypertrophy in cultured myoblasts (47, 50).

We previously reported that IL-15 enhances NK and ADCC activity of adult and neonatal MNC in cultures for up to 7 days (43). In this study, we present data to show that IL-15 enhances NK cytotoxicity and ADCC of neonatal cells and also increases the percentage and absolute number of NK cells in culture for 6 weeks or more. Prolonged stimulation of MNC from cord blood with IL-15 also results in a subpopulation of NK cells with unique phenotypic markers and high cytotoxic activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

MNC were obtained from healthy adult volunteers and from the umbilical cord of term newborn infants after normal vaginal delivery according to the guidelines established by the UCLA Human Subjects Protection Committee. Cord blood was collected into sterile heparinized tubes and processed within 24 h of birth. Cord blood was used to obtain neonatal lymphocyte populations, as there would be ethical concerns in obtaining peripheral blood from healthy newborns for a study such as this one in which there are no direct benefits for the infant.

Effector cells.

MNC were separated from heparinized blood using Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. The isolated cells were resuspended at a density of 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, Calif.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS). MNC were then placed in a 15-ml culture tube (Falcon 2095; Becton Dickinson, Oxnard, Calif.) or a 25-cm2 tissue culture flask (Sarstedt, Inc., Newton, N.C.) with no cytokines or with recombinant IL-12 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) and/or IL-15 (Immunex Corp., Seattle, Wash.) and/or IL-2 (Cetus, Emeryville, Calif.). The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 without cytokines or with various cytokine combinations and concentrations for periods of times ranging from 18 h to 12 weeks. Interleukin dosages for optimal in vitro NK activity were used as previously described (5, 6). The cytokines were added at the same dosages every 3 to 4 days to the cultures to maintain optimal concentrations in the longer experiments. The concentrations selected for this study allowed us to examine the effects of combining the cytokines and also to approximate levels that might be achieved pharmacologically. After incubation, the MNC were washed and resuspended to a density of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml for cytotoxicity assays.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Healthy adult and umbilical cord MNC were washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% FCS and 0.1% sodium azide and then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate- or phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies. Ten microliters of the appropriate fluorescent reagent was incubated with 5 × 106 cells for 20 to 30 min at 4°C in the dark. The antibodies used were Leu-11a (anti-CD16), Leu-19 (anti-CD56), and Leu-2a (anti-CD8) from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, Calif.). The cells were then washed twice with 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C.

The fluorescence staining was analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometer. Electronic gates were set to enable analysis of the fluorescence of the lymphocytes or monocytes in each preparation. The percentage of cells staining with each monoclonal antibody was determined by comparing each histogram with one from control cells stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate- or phycoerythrin-labeled anti-gamma-1 monoclonal antibodies.

Target cells.

Cytotoxicity was examined by measuring the release of 51Cr from target cells. The tumor cell line K562 was used as the target cells and prepared as previously described (49).

CEM.NKR cells (a NK-resistant human T lymphoblast tumor cell line) were maintained in long-term culture in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS (46). On the day of the assay, 2 × 106 to 5 × 106 CEM.NKR cells were pelleted in a 5-ml centrifuge tube, resuspended, and then incubated with 1 μg of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) gp120 recombinant protein strain MN (MicroGeneSys, Meriden, Conn.) per 2 × 106 targets and 100 μCi of 51Cr in a 37°C water bath for 2 h with mixing every 15 to 20 min. After incubation, the chromate-labeled cells were washed three times with 5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium, resuspended at a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml, and added to the wells.

NK assays and ADCC assays.

When K562 cells were used as targets, 104 cells in 100 μl were added to each well (final concentration, 5 × 104/ml) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS. To achieve a 25:1 effector-to-target cell ratio, 2.5 × 105 MNC were added to each well; 1.0 × 105 MNC were added for a 10:1 ratio. The final volume was 0.2 ml for all wells.

When CEM cells coated with HIV-1 gp120 protein were used as targets, HIV hyperimmune intravenous immunoglobulin (HIVIG; North American Biologicals, Miami, Fla.) at a dilution of 1:5,000 was used to assess ADCC. HIVIG is a 5% solution of 99% immunoglobulin G from pooled plasma samples from HIV-1 seropositive asymptomatic donors with CD4 counts of >400/mm3 and a high antibody titer to p24 HIV antigen (15).

The plates containing target cells and effector cells were centrifuged at 100 × g for 3 to 5 min and then incubated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator at various effector-to-target cell ratios as described above. All assays included additional wells with effector and target cells in the absence of antibody; the resulting cytotoxicity is referred to as “natural killing” or “NK activity.” We refer to the cells that have been stimulated with cytokines for several days as “activated NK” cells rather than “lymphokine activated,” as IL-15 is not a lymphokine. The incubation times for assays using K562 and CEM cells as targets are 3 and 4 h, respectively.

After incubation, plates were centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min. Culture supernatants (40% of total volume) were harvested, and cells were counted to assess 51Cr release. Specific lysis was determined by using the following formula: percent specific lysis = {[experimental counts per minute (cpm) − spontaneous cpm]/[total cpm − spontaneous cpm]} × 100. The mean total release and mean spontaneous release (in counts per minute) in this series of experiments were 5,422 ± 336 and 971 ± 119, respectively, for K562 cells and 7,245 ± 318 and 1,256 ± 87, respectively, for CEM cells. Due to the limited number of cells available for many of the assays, we could not include a third (higher) effector-to-target cell ratio, as required for generating lytic unit data to measure cytotoxicity.

Expansion.

Cell yield was determined in cultures incubated with or without cytokines with a beginning cell concentration of 106 cells/ml. Weekly cell counts were taken to monitor and tabulate changes in cell concentration. Cell cultures exceeding 1.2 × 106 cells/ml had additional volumes of RPMI 1640 medium added to achieve the original concentration (1 × 106 cells/ml). In computing the change in cell concentration, calculations were relative to the original cell concentration (106 cells/ml). Cell expansion was determined by the following formula: cell expansion = {[cell count × (original volume + added volume)]/[original volume]}.

Data analysis.

Student's t test (two-tailed) was used to compare the reported means with the standard errors for the different variables. The data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEMs); n refers to the number of experiments performed. The group means being compared were considered significantly different if P was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of IL-15 on CD16 and CD56 expression.

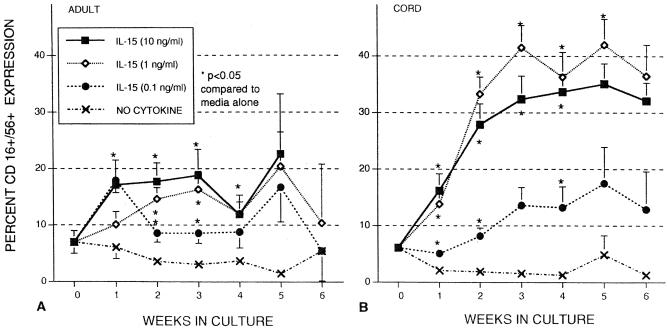

The percentages of adult and cord blood MNC expressing both NK markers (CD16 and CD56) were examined weekly during a 6-week incubation (Fig. 1). Expression of CD16+ CD56+ markers in freshly isolated cord MNC was 7.0% ± 2.4% (n = 6), decreasing to 1.3% ± 0.9% (n = 5) after 6 weeks of culture when no cytokines were present. The percentage of CD16+ CD56+ cells also declined in adult cells after incubation for 6 weeks in a manner similar to that of cord cells. When IL-15 (10 ng/ml) was added for 1 week, there was a significant increase in CD16+ CD56+ expression in both adult MNC (17.1% ± 4.4%) and cord MNC (16.2% ± 3.0%). Prolonged incubation with IL-15 (10 ng/ml) resulted in increased receptor expression in cord MNC, reaching 35.1% ± 3.6% by week 5. By contrast, CD16+ CD56+ expression on adult MNC was not that significantly increased after the first week of incubation, reaching 22.6% ± 3.9% by week 5. The effects of IL-15 (1 ng/ml) were similar to those of IL-15 (10 ng/ml), with approximately twice as many cord MNC expressing CD16+ CD56+ after 5 weeks compared to adult MNC. IL-15 (0.1 ng/ml) was less effective than the higher concentrations of IL-15 in inducing CD16+ CD56+ expansion but still higher than that of no cytokines. Thus, cord MNC were much more effective than adult MNC in generating CD16+ CD56+ cells after stimulation with IL-15 in these long-term cultures.

FIG. 1.

Effects of IL-15 on CD16+ CD56+ receptor expression of MNC from healthy adult controls (A) and umbilical cord blood (B). MNC were incubated without cytokines (no cytokine) or various concentrations of IL-15 (0.1, 1, and 10 ng/ml). Flow cytometry assays were conducted at weekly intervals to determine receptor expression. The data shown were compiled from samples from 44 cords and 15 adults and are expressed as means ± SEMs (error bars). The P value compares percent expression without cytokines to that of samples with cytokines.

Effects of IL-15 on CD3 and CD8 expression.

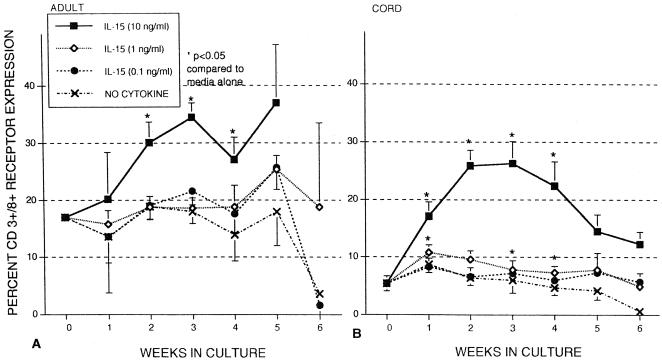

Adult control and cord blood MNC expression of both CD3 and CD8 (cytotoxic T cells) was also examined in the presence and absence of IL-15 (Fig. 2). Expression of CD3+ CD8+ markers in freshly isolated cord cells was 5.4% ± 1.3%, decreasing to 0.6 ± 0.6% after 6 weeks when incubated in medium only. The percentage of CD3+ CD8+ cells present in freshly isolated adult MNC was 17.0 ± 0.2 and also declined in the absence of cytokines. When IL-15 was added (10 ng/ml), CD3+ CD8+ expression increased in both cord and adult MNC, although there was a relatively greater response with the cord MNC. Cord MNC CD3+ CD8+ expression peaked at weeks 2 and 3 and then steadily declined. CD3+ CD8+ expression on adult cells also continued to increase after 2- and 3-week incubation with IL-15 (10 ng/ml), but a decline as seen with cord MNC was not as apparent. Lower concentrations of IL-15 did not have a significant effect on CD3 or CD8 expression in cord or adult MNC.

FIG. 2.

Effects of IL-15 on CD3+ CD8+ receptor expression of MNC from healthy adult controls (A) and umbilical cord blood (B). MNC were left untreated (no cytokine) or incubated with various concentrations of IL-15 (0.1, 1, and 10 ng/ml) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Flow cytometry assays were conducted at weekly intervals to determine receptor expression. The data shown were compiled from samples from 22 cords and 13 adults and are expressed as means ± SEMs (error bars). The P value compares percent expression without cytokines to that of samples with cytokines.

Emergence of CD8+ CD56+ population.

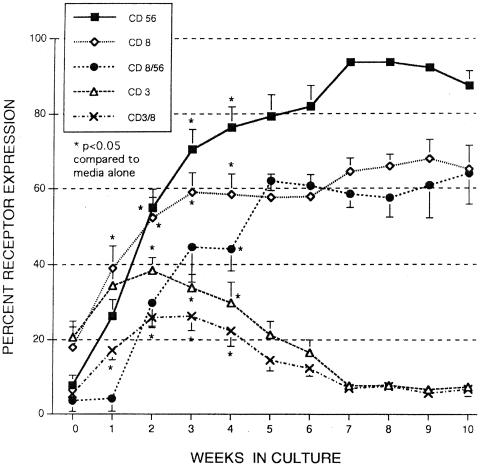

The data presented in Fig. 1B indicate that approximately 40% of cord MNC express both CD16 and CD56 after 6 weeks of incubation with IL-15 (10 ng/ml), but further analysis revealed that the total number of MNC expressing CD56+ was more than 80% by week 6, indicating there was approximately 40% of MNC that were CD16− CD56+. In Fig. 3, the incubation period of cord MNC has been extended to 10 weeks, and the total number of cells expressing CD56+ now exceeds 90%.

FIG. 3.

Effects of IL-15 (10 ng/ml) on receptor expression of MNC from umbilical cord blood. MNC were incubated in the presence of IL-15 (10 ng/ml), and flow cytometry assays were conducted weekly to determine receptor expression. The data shown was compiled from 14 cords (although data were not available for every time point) and are expressed as means ± SEMs (error bars). The P value compares percent expression without cytokines to that of samples with cytokines. The total percentages of cells staining for a single receptor (CD3, CD8, or CD56) and cells staining for two receptors (CD3+ CD8+ or CD8+ CD56+) are shown.

Further analysis of data presented in Fig. 2B also showed that the total number of cord MNC expressing CD8 far exceeded those staining for both CD3 and CD8. This discrepancy is magnified when cells were cultured for 10 weeks; the number of CD3+ CD8+ cells greatly declined, whereas the total number of CD8+ cells exceeded 60% (Fig. 3). Note also that the total number of CD3+ cells also greatly declined, indicating there were no CD3+ CD8− cells or <10% CD3+ CD8+ cells remaining.

When the MNC were stained for both CD8 and CD56, we find that almost all CD8 cells (approximately 60% of MNC) were also stained for CD56 (Fig. 3). This CD8+ CD56+ population is not present in fresh cord blood and, thus, is unique in its phenotypic expression. Incubation of cord MNC with IL-15 at 1 ng/ml also resulted in the majority of cells (59.7% ± 5.9%) staining for both CD8 and CD56 after 6 weeks of culture. CD8+ CD56+ cells are not normally found in the peripheral blood of adults, but they may be generated after culture with IL-15, although not to the extent seen with cord cells (up to 30% after 9 weeks with adult cells).

Triple staining for CD8, CD16, and CD56 were done on selected cord MNC cultures grown for 3 to 6 weeks. Approximately 50% of the CD8+ CD56+ cells were also positive for CD16 (CD8+ CD16+ CD56+), making an equivalent number of CD8+ CD16− CD56+ cells. There was a smaller percentage (about 20% of the total CD16+ CD56+ population) that was CD8− (CD8− CD16+ CD56+). No CD8+ CD16+ CD56− cells were found in any of the assays.

Thus, most cells with the typical NK phenotype (CD16+ CD56+) were also CD8+ after culture with IL-15, although an equivalent population of CD8+ CD16− CD56+ cells also developed. After 6 weeks of culture, there are very few CD3+ cells (T cells) remaining (Fig. 3), which may indicate that two subpopulations of NK cells have emerged in these long-term cultures, a CD8+ CD16+ CD56+ subpopulation and a CD8+ CD16− CD56+ subpopulation.

Effects of other cytokines on CD16 and CD56 expression.

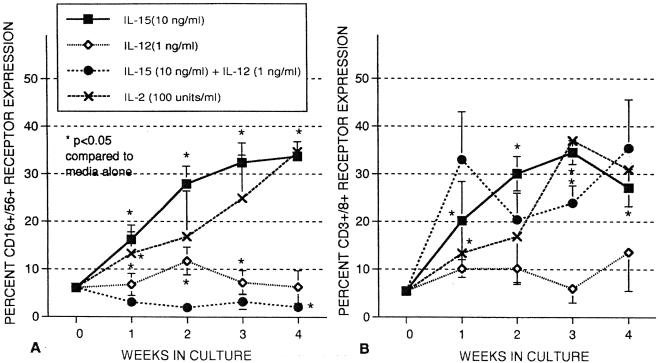

We have previously shown that incubation of cord MNC with IL-12 (1 ng/ml) alone will increase the percentage of CD16+ CD56+ cells after 1 week, although the percentage of CD16+ CD56+ greatly declines if IL-12 is combined with IL-15. Likewise, IL-12 will enhance cytotoxicity of cord MNC after 1 week, but it inhibits the cytotoxicity of IL-15 when given with IL-15. In Fig. 4, we have extended these studies and found that IL-12, alone and particularly in combination with IL-15, greatly diminishes the percentage of CD16+ CD56+ cells by week 4. IL-12 also greatly decreases the total number of cells recovered (not shown), making studies longer than 4 weeks with IL-12 very difficult due to lack of cells remaining in culture. IL-12 has a similar inhibitory effect on NK cell cytotoxicity as discussed below.

FIG. 4.

Effect of cytokines on CD3 CD8 (A) and CD16 CD56 (B) receptor expression of MNC from umbilical cord blood. MNC were incubated in the presence of IL-15 (10 ng/ml), IL-12 (1 ng/ml), and IL-15 plus IL-12. Flow cytometry assays were conducted at weekly intervals to determine receptor expression. The data shown were compiled from samples from 18 cords and 12 adults and are expressed as means ± SEMs (error bars). The P value compares percent expression without cytokines to that of samples with cytokines.

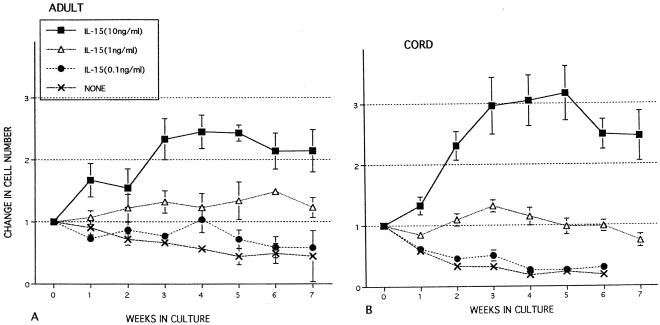

Effects of IL-15 on expansion of cord and adult MNC.

Expansion of adult and cord MNC was monitored over an 8-week period in as shown in Fig. 5. In medium alone, a gradual reduction in adult MNC was observed over the incubation period. However, there was a more profound decrease in the cord MNC without cytokines, with the loss of almost all cells after 6 weeks of culture (Fig. 5B). Incubation with IL-15 at 1 ng/ml maintained levels of cord and adult MNC at approximately 106 cells/ml with no net change. IL-15 at 10 ng/ml resulted in expansion of both cord and adult MNC, with cord cells expanding more than threefold by week 5. Cord and adult MNC incubated in 0.1 ng of IL-15 per ml declined in cell number, similar to cultures with no cytokines. Incubation of cord MNC in IL-2 (100 U/ml) also expanded at a rate similar to that of IL-15 at 10 ng/ml (not shown). Cord and adult MNC incubated in IL-12 (1 ng/ml) also declined in number after 2 weeks of culture and continued to decrease in subsequent weeks.

FIG. 5.

Long-term effects of cytokines on MNC expansion from healthy adult controls (A) and umbilical cord blood (B). MNC were left untreated (no cytokine) or incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 with various concentrations of IL-15 (ng/ml) for up to 8 weeks. Cells were subsequently maintained at a cell concentration of 106 cells/ml by adding additional medium at weekly intervals. The data shown were compiled from samples from 19 cords and 7 adults and are expressed as means ± SEMs (error bars).

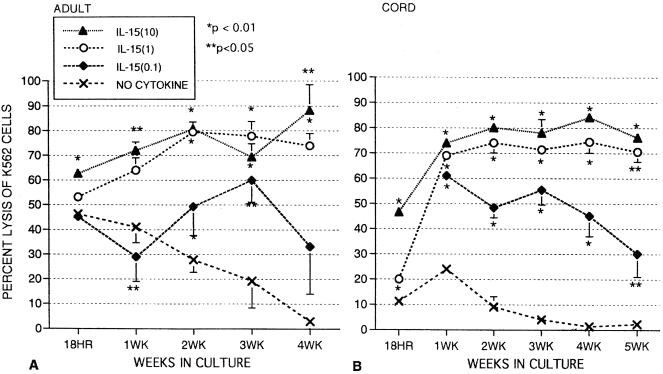

Effects of IL-15 on natural killer activity against K562 cells.

In the absence of cytokines, cord NK activity was much lower than that of adults, although NK activity for both adult and cord cells dropped to zero by week 4 without IL-15. Overnight (18-h) incubation with IL-15 at 1.0 and 10 ng/ml enhanced NK activity of cord MNC, and K562 lysis reached approximately 70% after 1 week as previously reported (43). This high level of cytotoxicity was maintained for 5 weeks (Fig. 6B) and continued to be high in some cords incubated with IL-15 for as long as 12 weeks (not shown). Adult MNC, starting at a much higher baseline NK activity in the absence of cytokines, still significantly increased NK activity after overnight incubation with IL-15 at 10 ng/ml. and NK activity tended to increase over 4 weeks (Fig. 6A). With the lowest concentration of IL-15 (0.1 ng/ml), cord NK activity significantly increased to approximately 60% and then gradually declined over 5 weeks. Adult MNC NK activity was slightly lower after 1 week with IL-15 at 0.1 ng/ml but was higher than the values for medium alone after 2 and 3 weeks of incubation. Note that the dose response of NK activity in Fig. 6 resembles the percentage of cells expressing the CD16+ CD56+ NK phenotype with IL-15 as shown in Fig. 1, particularly with regard to the cord cells.

FIG. 6.

Long-term effects of IL-15 on NK activity against K562 cells with MNC from healthy adult controls (A) or umbilical cord blood (B) in medium alone or in the presence of IL-15 (0.1, 1, and 10 ng/ml) at an effector-to-target cell ratio of 25:1. The data shown were compiled from samples from 20 cords and 9 adults and are expressed as means ± SEMs (error bars). The P value compares percent expression without cytokines to that of samples with cytokines.

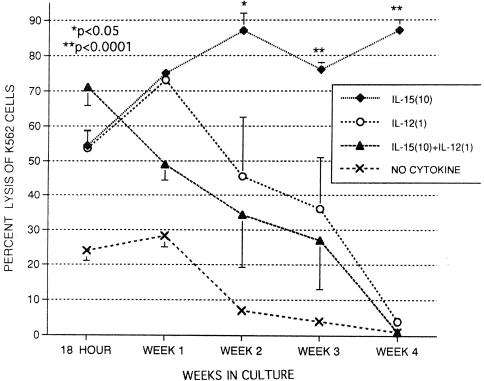

Effects of IL-15 and IL-12 on NK activity.

The effects of IL-15 and IL-12 alone and together on cord NK activity are shown in Fig. 7 at a 25:1 effector-to-target cell ratio. IL-15 at 10 ng/ml markedly enhances NK activity for the 4-week period as shown previously. IL-12 alone greatly increased K562 lysis (54.6% ± 4.3%) compared to medium alone (24.0% ± 2.9%) in 18-h assays. IL-12 alone continued to increase NK activity after 1 week of culture, but NK activity then declined after 2 weeks and was essentially zero after 4 weeks in great contrast to IL-15. The combination of IL-15 and IL-12 resulted in greater cytotoxicity than either cytokine alone after an 18-h incubation but then declined after week 1. NK activity also eventually declined to zero by week 4 with the combination of the cytokines. This observation suggests that IL-12 inhibits IL-15-induced activity and loses its stimulatory properties by week 2. Cord MNC incubated with IL-15 alone for 3 weeks also declined in NK activity within a week after the addition of IL-12, indicating that IL-12 was inhibitory even if not present at the start of culture (not shown). Thus, IL-12 appears to inhibit cytotoxic activity in longer cultures, similar to the effect seen on CD16+ CD56+ expression in Fig. 4.

FIG. 7.

Long-term effects of IL-15 and IL-12 on NK activity against K562 cells with MNC from umbilical cord blood alone (no cytokine) or in the presence of IL-15 (10 ng/ml) and/or IL-12 (1 ng/ml) for periods of time ranging from 18 h to 4 weeks. MNC were tested at an effector-to-target cell ratio of 25:1. The data shown were compiled from samples from 12 cords and are expressed as means ± SEMs (error bars). The P values compare percent expression without cytokines to that of samples with cytokines.

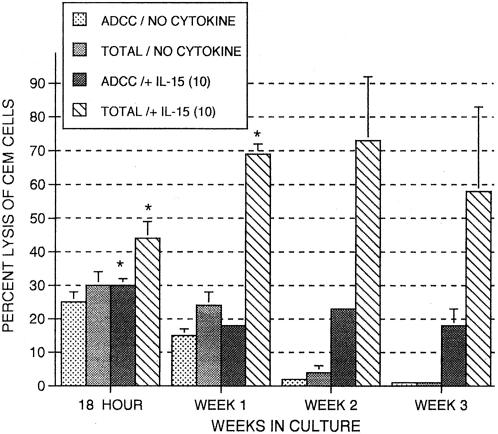

Enhancement of activated NK and ADCC against gp120-coated CEM.NKR cells.

Cord cytotoxicity was also tested using CEM.NKR cells coated with HIV protein gp120 in the absence of antibody (NK activity) or in the presence of antibody (ADCC activity). In Fig. 8, ADCC activity and total cytotoxic activity, which is the sum of ADCC and NK activity, are shown. IL-15 maintained ADCC activity throughout the 3-week period, although ADCC activity dropped to zero by the third week in the absence of IL-15. By contrast, IL-15 had a more positive effect on total cytotoxicity through the 3 weeks, indicating a greater effect on NK activity. Thus, IL-15 does improve or at least maintain ADCC activity in cord MNC as well as enhance activated NK activity.

FIG. 8.

Long-term effects of IL-15 on MNC-mediated ADCC of CEM cells coated with HIV antigen gp120 using MNC from umbilical cord blood as effectors. MNC were incubated for periods of time ranging from 18 h to 3 weeks alone (no cytokine) or in the presence of IL-15 (10 ng/ml) and tested at an effector-to-target cell ratio of 25:1. The term “total” in the figure refers to total cytotoxic activity, that is, NK plus ADCC minus spontaneous release. The data shown were compiled from samples from two cords and are expressed as means ± SEMs (error bars). The P value (P < 0.05) (indicated by an asterisk) compares percent expression without cytokines to that of samples with cytokines.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that IL-15 has many similarities to IL-2 in regard to its ability to stimulate NK proliferation and activation (38, 39, 43). These similarities might have been anticipated, as IL-2 and IL-15 bind to the same β and γ chains of the IL-2R complex, although IL-15 does bind to a novel α chain (IL-15R α).

IL-15 differs from IL-2; IL-15 is produced primarily by monocytes and epithelial cells, whereas IL-2 is generated primarily in activated T lymphocytes. IL-15 appears to be more specific than IL-2 in differentiation of NK cells from bone marrow or fetal stem cells in two recent studies (22, 26). IL-15 is also a potent chemoattractant and activator of NK cells. Studies in mice showed that IL-15 was responsible for preventing bacterial infection by attracting and activating NK cells at the sites where bacteria were inoculated (26, 40). IL-15 was found to be the most potent cytokine for activating intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes in human studies. These intestinal lymphocytes are predominantly CD8+ T cells, and IL-15 was found to be 1,000 times more potent than IL-2 in stimulating blastogenesis and also better than IL-2 in inducing cytotoxicity (18). The fact that IL-15 is produced by epithelial cells, as well as monocytes, increases its distribution throughout the body, particularly in mucosal tissues.

Thus, although IL-2 and IL-15 are similar, there are distinct differences in these two cytokines, and in many studies, IL-15 is superior with regard to stimulating differentiation and activation of specific lymphocyte populations. In the present study, we have focused on the ability of IL-15 to affect differentiation, expansion, and activation of neonatal NK cells in long-term culture.

IL-15 was able to dramatically increase the percentage and numbers of NK cells (CD16+ CD56+) in cord blood cell cultures as shown in Fig. 1. These NK cells could be maintained in culture for up to 12 weeks. IL-15 also increased the percentage of NK cells in cultures of adult MNC (Fig. 1A), although the percentage of CD16+ CD56+ cells was about half that of the cord cells. The greater response with the cord cells is likely due to differentiation of stem cells (CD34+) and NK progenitors found in cord blood (9, 38, 51, 52). Similar effects of IL-15 on differentiation are seen when stem cells (CD34+) are collected from the bone marrow of adults or from peripheral blood after granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatment in adult donors (9, 52).

A relatively large increase in the percentage of CD3+ CD8+ cells or cytotoxic or suppressor T cells was also seen in cord MNC with IL-15 (Fig. 2B), but the percentage of CD3+ CD8+ cells began to decline after 4 weeks and dropped to less than 10% in cultures incubated for up to 10 weeks (Fig. 3). Also noted was the finding that only the highest concentration of IL-15 (10 ng/ml) resulted in a substantial increase in the percentage of CD3+ CD8+ cells. IL-15 appeared to have a greater effect on the percentage of CD3+ CD8+ cells in cultures of adult MNC (Fig. 2A), although more CD3+ CD8+ cells were present at the start of culture.

IL-15 had its most profound effects on the CD8+ CD56+ subpopulation of cells as shown in Fig. 3. CD8+ CD56+ cells are very rare in fresh cord blood but constitute more than 60% of the cells in cultures over 6 weeks in age. About 50% of these CD8+ CD56+ cells are also CD16+ (CD8+ CD16+ CD56+), and these cells most likely are a NK cell subpopulation. These cells maintain high NK activity (Fig. 6), whereas the percentage of CD3+ cells greatly diminishes in long-term culture. Other researchers showed that stimulation of purified CD 34+ cord cells with IL-15 also results in a high percentage of CD56+ cells (8). Long-term culture of adult peripheral blood MNC resulted in a smaller percentage of CD8+ CD56+ cells (approximately 30% of total) in 6-week cultures.

IL-15 stimulation also resulted in an expansion of the total number of cord and adult MNC only at the 10 ng/ml concentration. However, as there was also a dramatic increase in the percentage of NK cells (CD16+ CD56+) with IL-15, there is a much greater increase in the total numbers of NK cells resulting from IL-15 stimulation. Patients receiving IL-2 for treatment of cancer also have increased numbers of NK cells in their peripheral blood (16), and this increase might also be anticipated in the potential clinical use of IL-15.

We and others (39) previously reported that IL-15 greatly enhances the NK cytotoxicity of cord cells in short-term culture (1 to 10 days), and now we find this enhancement is sustained in long-term cultures (Fig. 6) even with the 1-ng/ml concentration of IL-15. Cytotoxicity was also enhanced using CEM cells coated with the HIV gp120 antigen (Fig. 8). In these assays, lysis of the CEM cells may occur by an ADCC mechanism when antibody (anti-HIV antisera) is present; it may also occur directly by activated NK cells, which is evident in the absence of antibody. IL-15 had a greater impact on the NK component (noted by greater total lysis) and at least maintained ADCC activity, which was absent after 3 weeks of culture without IL-15.

IL-12 is another cytokine that stimulates NK, but its effects appear to be short lived in the present studies. If IL-12 was present, the number of CD16+ CD56+ cells declined to levels similar to those in cultures with no cytokines present (Fig. 4). When IL-15 was present with IL-12, even greater declines in the percentage of CD16+ CD56+ cells occurred, indicating that IL-12 was actually inhibiting NK cells. IL-12 greatly enhanced killing of K562 cells by cord MNC after 1 week, but the enhancement of cytotoxicity greatly declined and was essentially zero after 4 weeks of culture (Fig. 7). IL-12 also inhibited enhancement of IL-15 on cytotoxicity, corresponding to the decline in CD16+ CD56+ cells seen with the combination of the two cytokines, IL-12 alone or in combination with IL-15.

Thus, IL-15 is able to promote the propagation and activation of NK cells in long-term culture of MNC from cord blood. Although these results were obtained from lymphocytes obtained from cord blood, it seems likely that similar results would be obtained using NK cells from peripheral blood from newborns. Studies using peripheral blood are advised if clinical studies using IL-15 are anticipated. It may play a beneficial role in a number of clinical settings, such as stem cell transplantation, immunotherapy for cancer, and treatment of HIV infection. It should be considered an alternative to present clinical protocols employing IL-2. Although IL-2 and IL-15 share many similarities, IL-15 offers selective properties that may be advantageous in certain clinical situations. The clinical use of IL-15 may be of particular benefit in combating viral infections in newborns and others who have become immunocompromised. Treatment with IL-15 may be of particular usefulness in herpesvirus infections, as patients with decreased NK function are more susceptible to this virus.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation in the form of Student Intern Awards to Sunwoong Choi and Quoc Nguyen and by stipends from the UCLA Academic Senate to Sunwoong Choi, Vaninder Chhabra, and Quoc Nguyen.

IL-15 was a gift of the Immunex Corporation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allavena, P., G. Giardina, G. Bianchi, and A. Mantovani. 1997. IL-15 is chemotactic for natural killer cells and stimulates their adhesion to vascular endothelium. J. Leukoc. Biol. 61:729-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, D., S. Kumaki, M. Ahdieh, M. Bertles, A. Tometsko, J. Loomis, J. G. Giri, N. G. Copeland, D. J. Gilbert, N. A. Jenkins, V. Valentine, D. N. Shapiro, S. W. Morris, L. S. Park, and D. Cosman. 1995. Functional characterization of the human interleukin-15 receptor α chain and close linkage of IL15RA and IL2RA genes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:29862-29869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansart-Pirenne, H., F. Paillard, D. De Groote, A. Eljaafari, S. Le Gac, P. Blot, P. Franchimont, C. Vaqero, and G. Sterkers. 1994. Defective cytokine expression but adult type T-cell receptor, CD8, and p56lck modulation in CD3- or CD2-activated T-cells from neonates. Pediatr. Res. 37:64-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armant, M., G. Delespesse, and M. Sarfati. 1995. IL-2 and IL-7 but not IL-12 protect natural killer cells from death by apoptosis and up-regulate bcl-2 expression. Immunology 85:331-337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baum, L. L., K. J. Cassutt, K. Knigge, R. Khattri, J. Margolick, C. Rinaldo, C. A. Kleeberger, P. Nishanian, D. R. Henrard, and J. Phair. 1996. HIV-1 gp120-specific antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity correlates with rate of disease progression. J. Immunol. 157:2168-2173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnema, J. D., K. A. Rivlin, A. T. Ting, R. A. Schoon, R. T. Abraham, and P. J. Leibson. 1994. Cytokine-enhanced NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Positive modulatory effects of IL-2 and IL-12 on stimulus-dependent granule exocytosis. J. Immunol. 152:2098-2104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton, J. D., R. N. Bamford, C. Peters, A. J. Grant, G. Kurys, C. K. Goldman, J. Brennan, E. Roessler, and T. A. Waldmann. 1994. A lymphokine, provisionally designated interleukin T and produced by a human adult T-cell leukemia line, stimulates T-cell proliferation and the induction of lymphokine-activated killer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:4935-4939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bykovskaia, S., M. Buffo, H. Zhang, M. Bunker, M. L. Levitt, M. Agha, S. Marks, C. Evans, P. Ellis, M. R. Shurin, and J. Shogan. 1999. The generation of human dendritic and NK cells from hematopoietic progenitors induced by interleukin-15. J. Leukoc. Biol. 66:659-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carayol, G., C. Robin, J. H. Bourhis, A. B. Griscelli, S. Chouaib, L. Coulombel, and A. Caignard. 1998. NK cells differentiated from bone marrow, cord blood and peripheral blood stem cells exhibit similar phenotype and functions. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:1991-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carson, W. E., J. G. Giri, M. J. Lindemann, M. L. Linett, M. Ahdieh, R. Paxton, D. Anderson, J. Eisenman, K. Grabstein, and M. A. Caligiuri. 1994. Interleukin (IL) 15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J. Exp. Med. 180:1395-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson, W. E., M. E. Ross, R. A. Baiocchi, M. J. Marien, N. Boiani, K. Grabstein, and M. A. Caligiuri. 1995. Endogenous production of interleukin 15 by activated human monocytes is critical for optimal production of interferon-γ by natural killer cells in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 96:2578-2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chehimi, J., N. M. Valiante, A. D'Andrea, M. Regaraju, Z. Rosado, M. Kobayashi, B. Perussia, S. F. Wolf, S. E. Starr, and G. Trinchieri. 1993. Enhancing effect of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF/interleukin-12) on cell-mediated cytotoxicity against tumor-derived and virus-infected cells. J. Immunol. 23:1825-1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chehimi, J., S. E. Starr, I. Frank, M. Rengaraju, S. J. Jackson, C. Llanes, M. Kobayashi, B. Perussia, D. Young, E. Nickbarg, S. F. Wolf, and G. Trinchieri. 1992. Natural killer (NK) cell stimulatory factor increases the cytotoxic activity of NK cells from both healthy donors and human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J. Exp. Med. 175:789-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clerici, M., A. Sarin, R. L. Coffman, T. A. Wynn, S. P. Blatt, C. W. Hendrix, S. F. Wolf, G. M. Shearer, and P. A. Henkart. 1994. Type 1/type 2 cytokine modulation of T-cell programmed death as a model for human immunodeficiency virus pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11811-11815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummins, L. M., K. J. Weinhold, T. J. Matthews, A. J. Langlois, C. F. Perno, R. M. Condie, and J. Allain. 1991. Preparation and characterization of an intravenous solution of IgG from human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive donors. Blood 77:1111-1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Jong, J. L. O., N. L. Farber, B. R. Javorsky, M. J. Lindstrom, J. A. Hank, and P. M. Sondel. 1998. Differential quantitative effects of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-15 on cytotoxic activity and proliferation by lymphocytes from patients receiving in vivo IL-2 therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 4:1287-1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doherty, T. M., R. A. Seder, and A. Sher. 1996. Induction and regulation of IL-15 expression in murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 156:735-741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebert, E. C. 1998. Interleukin-15 is a potent stimulant of intraepithelial lymphocytes. Gastroenterology 115:1439-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gamero, A. M., D. Ussery, D. S. Reintgen, C. A. Puleo, and J. Y. Djeu. 1995. Interleukin 15 induction of lymphokine-activated killer cell function against autologous tumor cells in melanoma patient lymphocytes by a CD18-dependent, perforin-related mechanism. Cancer Res. 55:4988-4994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giri, J. G., M. Ahdieh, J. Eisenmann, K. Shanebeck, K. Grabstein, S. Kumaki, A. Namen, L. S. Park, D. Cosman, and D. Anderson. 1994. Utilization of the β and γ chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. EMBO J. 13:2822-2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giri, J. G., S. Kumaki, M. Ahdieh, D. J. Friend, J. Loomis, K. Shanebeck, R. DuBose, D. Cosman, L. S. Park, and D. Anderson. 1995. Identification and cloning of a novel IL-15 binding protein that is structurally related to the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor. EMBO J. 14:3654-3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosselin, J., A. Tomolu, R. C. Gallo, and L. Flamand. 1999. Interleukin-15 as an activator of natural killer cell-mediated antiviral response. Blood 94:4210-4219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grabstein, K. H., J. Eisenman, K. Shanebeck, C. Rauch, S. Srinivasan, V. Fung, C. Beers, J. Richardson, M. A. Schoenborn, M. Ahdieh, L. Johnson, M. R. Alderson, J. D. Watson, D. M. Anderson, and J. G. Giri. 1994. Cloning of a novel T cell growth factor that interacts with the beta chain of interleukin-2 receptor. Science 264:965-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassan, J., and R. J. Reen. 1996. Reduced primary-antigen specific T-cell precursor frequencies in neonates is associated with deficient interleukin-2 production. Immunology 87:604-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henney, C. S., K. Kuribayashi, D. E. Kern, and S. Gillis. 1981. Interleukin-2 augments natural killer activity. Nature 291:335-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirose, K., H. Nishimura, T. Matsuguchi, and Y. Yoshikai. 1999. Endogeneous IL-15 might be responsible for early protection by natural killer cells against infection with an avirulent strain of Salmonella choleraesuis in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 66:382-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins, M., J. Mills, and S. Kohl. 1993. Natural killer cytotoxicity and antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity of human immunodeficiency virus-infected cells by leukocytes from human neonates and adults. Pediatr. Res. 33:469-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jewett, A., and B. Bonavida. 1994. Activation of human immature natural killer cell subset by IL-12 and its regulation by endogenous TNF-α and IFN-γ secretion. Cell. Immunol. 154:273-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanai, T., E. K. Thomas, Y. Yasutomi, and N. L. Letvin. 1996. IL-15 stimulates the expansion of AIDS virus-specific CTL. J. Immunol. 157:3681-3687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohl, S., M. Sigaroudinia, E. D. Charlebois, and M. A. Jacobson. 1996. Interleukin-12 administered in vivo decreases human NK cell cytotoxicity and antibody dependent cytotoxicity to human immunodeficiency virus-infected cells. J. Infect. Dis. 174:1105-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohl, S., M. S. West, and L. S. Loo. 1988. Defects in interleukin-2 stimulation of neonatal natural killer cytotoxicity to herpes simplex virus-infected cells. J. Pediatr. 112:976-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landers, D. V., J. P. Smith, C. K. Walker, T. Milam, L. Sanchez-Pescador, and S. Kohl. 1994. Human fetal antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity to herpes simplex virus-infected cells. Pediatr. Res. 35:289-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanier, L. L., J. H. Phillips, J. Hackett, M. Tutt, and V. Kumar. 1986. Natural killer cells: definition of a cell type rather than a function. J. Immunol. 137:2735-2739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lau, A. S., M. Sigaroudinia, M. C. Yeung, and S. Kohl. 1995. Interleukin-12 induces interferon-γ expression and natural killer cytotoxicity in cord blood mononuclear cells. Pediatr. Res. 39:150-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, S. M., Y. Suen, L. Chang, V. Bruner, J. Quian, J. Indes, E. Knoppel, C. van de Ven, and M. S. Cairo. 1996. Decreased interleukin-12 (IL-12) from activated cord versus adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells and upregulation of interferon-γ, natural killer, and lymphokine-activated killer activity by IL-12 in cord blood mononuclear cells. Blood 88:945-954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leibson, P. J., M. H. Laszlo, G. S. Douvas, and A. R. Hayward. 1986. Impaired neonatal natural killer-cell activity to herpes simplex virus: decreased inhibition of viral replication and altered response to lymphokines. J. Clin. Immunol. 6:216-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis, D. B., C. C. Yu, J. Meyer, B. K. English, S. J. Kahn, and C. B. Wilson. 1991. Cellular and molecular mechanisms for reduced interleukin-4 and interferon-γ production by neonatal T-cells. J. Clin. Investig. 87:194-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin, S. J., H. C. Chao, and D. C. Yan. 2001. Phenotypic changes of T-lymphocyte subsets induced by interleukin-12 and interleukin-15 in umbilical cord vs peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 12:21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin, S. J., M. H. Yang, H. C. Chao, M. L. Kuo, and L. Huang. 2000. Effect of interleukin-15 and Flt3-ligand on natural killer cell expansion and activation: umbilical vs adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 11:168-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitani, A., H. Nishimura, K. Hirose, J. Washizu, Y. Kimura, S. Tanaka, and G. Yamamoto. 1999. Interleukin-15 production at the early stage after oral infection with Listeria monocytogenes in mice. Immunology 97:92-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naume, B., M. Gately, and T. Espevik. 1992. A comparative study of IL-12 (cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor)-, IL-2- and IL-7-induced effects on immunomagnetically purified CD56+ NK cells. J. Immunol. 148:2429-2436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson, D. L., C. C. Kurman, M. E. Fritz, B. Boutin, and L. A. Rubin. 1986. The production of soluble and cellular interleukin-2 receptors by cord blood mononuclear cells following in vitro activation. Pediatr. Res. 20:136-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen, Q. H., R. L. Roberts, B. J. Ank, S. J. Lin, E. K. Thomas, and E. R. Stiehm. 1998. Interleukin (IL)-15 enhances antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and natural killer activity in neonatal cells. Cell. Immunol. 185:83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogata, K., H. Tamua, N. Yokose, E. An, K. Dan, H. Hamaguchi, H. Sakamaki, Y. Onozawa, S. C. Clark, and T. Nomura. 1995. Effects of interleukin-12 on natural killer cell cytotoxicity and the production of interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Br. J. Haematol. 90:15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osugi, Y., J. Hara, H. Kurahashi, N. Sakata, M. Inoue, K. Yumura-Yagi, K. Kawa-Ha, S. Okada, and A. Tawa. 1995. Age-related changes in surface antigens on peripheral lymphocytes of healthy children. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 100:543-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips, J. H., and L. L. Lanier. 1986. Dissection of the lymphokine-activated killer phenomenon: relative contribution of peripheral blood natural killer cells and T-lymphocyte cytolysis. J. Exp. Med. 164:814-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinn, L. S., K. L. Haugk, and K. H. Grabstein. 1995. Interleukin-15: a novel anabolic cytokine for skeletal muscle. Endocrinology 136:3669-3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robertson, M. J., and J. Ritz. 1990. Biology and clinical relevance of human natural killer cells. Blood 76:2421-2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stiehm, E. R., R. L. Roberts, B. J. Ank, S. Plaeger-Marshall, S. Salman, L. Shen, and M. Fanger. 1994. Comparison of cytotoxic properties of neonatal and adult neutrophils and monocytes and enhancement by cytokines. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1:342-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tagaya, Y., R. N. Bamford, A. P. DeFilippis, and T. A. Waldmann. 1996. IL-15: a pleiotropic cytokine with diverse receptor/signaling pathways whose expression is controlled at multiple levels. Immunity 4:329-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams, N. S., J. Klem, I. J. Puzanov, P. V. Sivakumar, M. Bennet, and V. Kumar. 1999. Differentiation of NK1.1+, Ly49+ NK cells from flt3+ multipotent marrow progenitor cells. J. Immunol. 163:2648-2656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu, H., T. A. Fehniger, P. Fuchshuber, K. S. Thiel, E. Vivier, W. E. Carson, and M. A. Caligiuri. 1998. Flt3 ligand promotes the generation of a distinct CD34+ human natural killer cell progenitor that responds to interleukin-15. Blood 92:3647-3657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zambello, R., M. Facco, L. Trentin, R. Sancetta, C. Tassinari, A. Perin, A. Milani, G. Pizzolo, F. Rodeghiero, C. Agostini, R. Meazza, S. Ferrini, and G. Semenzato. 1997. Interleukin-15 triggers the proliferation and cytotoxicity of granular lymphocytes in patients with lymphoproliferative disease of granular lymphocytes. Blood 89:201-211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]