Abstract

Estrogen receptor α (ERα) signaling is paramount for normal mammary gland development and function and the repression of breast cancer. ERα function in gene regulation is mediated by a number of coactivators and corepressors, most of which are known to modify chromatin structure and/or influence the assembly of the regulatory complexes at the level of transcription initiation. Here we describe a novel mechanism of attenuating the ERα activity. We show that cofactor of BRCA1 (COBRA1), an integral subunit of the human negative elongation factor (NELF), directly binds to ERα and represses ERα-mediated transcription. Reduction of the endogenous NELF proteins in breast cancer cells using small interfering RNA results in elevated ERα-mediated transcription and enhanced cell proliferation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation reveals that recruitment of COBRA1 and the other NELF subunits to endogenous ERα-responsive promoters is greatly stimulated upon estrogen treatment. Interestingly, COBRA1 does not affect the estrogen-dependent assembly of transcription regulatory complexes at the ERα-regulated promoters. Rather, it causes RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) to pause at the promoter-proximal region, which is consistent with its in vitro biochemical activity. Therefore, our in vivo work defines the first corepressor of nuclear receptors that modulates ERα-dependent gene expression by stalling RNAPII. We suggest that this new level of regulation may be important to control the duration and magnitude of a rapid and reversible hormonal response.

Keywords: Nuclear receptor, transcriptional repression, COBRA1, NELF, RNAPII, estrogen

Estrogen receptor α (ERα) belongs to the nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily that can regulate gene expression in a ligand-dependent and/or -independent manner (Nilsson et al. 2001). Upon binding to ligand such as 17β-estradiol (E2), ERα undergoes conformational changes and dissociates from chaperone proteins. An “activated” ERα dimerizes, binds to the estrogen response elements (EREs), and stimulates transcription of a variety of E2-responsive genes. An alternative mode of ERα action involves indirect association of ERα with DNA through binding to other site-specific transcription factors (e.g., AP1 and Sp1; Kushner et al. 2000). In addition to the ligand-dependent activation process, ERα can also be activated by multiple growth factor-mediated signaling pathways (Weigel and Zhang 1998). Ultimately, ERα enhances the rate of transcription initiation by nucleating the assembly of transcription regulatory complexes at the promoter regions of responsive genes (Glass and Rosenfeld 2000; McKenna and O'Malley 2002). Recent studies also indicate that recruitment of multiple coregulators and the basal transcription machinery occurs in a sequential and cyclic fashion, which is believed to be important for continuously sensing and responding to the ligand signaling (Shang et al. 2000; Metivier et al. 2003). Thus, the recurring mechanistic themes in regulating ERα-mediated transcription involve chromatin modification and communications between hormone receptors and the basal transcription machinery at the level of transcription initiation (Glass and Rosenfeld 2000; McKenna and O'Malley 2002).

A wealth of evidence strongly supports the paramount importance of the ERα–estrogen signaling pathway to breast cancer development (Persson 2000; Foster et al. 2001; Ali and Coombes 2002). The recent findings that breast cancer susceptibility gene product BRCA1 is a corepressor of ERα provide a potential molecular explanation for the tissue-specific nature of BRCA1-associated cancer (Fan et al. 1999, 2001; Zheng et al. 2001). However, cancer-causing mutations of BRCA1 are predominantly associated with the familial form of breast cancer, which only accounts for 5%–10% of breast cancer. Therefore, it is conceivable that additional factors with a similar corepressor activity may participate in the same regulatory process, defects of which may contribute to the etiology of the sporadic form of breast cancer. Cofactor of BRCA1 (COBRA1) was isolated as a BRCA1-interacting protein that exhibits a similar chromatin reorganizing activity as BRCA1 (Ye et al. 2001). It was subsequently found through an independent study to be identical to NELF-B, an integral subunit of the human negative transcription elongation factor (NELF) complex (Narita et al. 2003). NELF is a four-subunit complex (A, B, C/D, and E) that is biochemically purified based upon its role in repressing RNA polymerase II (RNAPII)-dependent transcription elongation in vitro (Yamaguchi et al. 1999). NELF-A and NELF-E bind to RNAPII and RNA, respectively, and both interactions are critical for NELF function in transcriptional pausing in vitro (Yamaguchi et al. 2002; Narita et al. 2003). Although COBRA1 (NELF-B) and NELF-C/D are both required for the assembly of a functional NELF complex, their biochemical functions in the context of the NELF complex remain to be elucidated.

Emerging evidence indicates that in addition to transcription initiation, the RNAPII-mediated transcription elongation is another important step in gene expression that is subject to regulation by multiple positive and negative regulatory protein complexes in response to various exogenous stimuli (Orphanides and Reinberg 2000; Winston 2001; Zorio and Bentley 2001). In vitro biochemical work shows that NELF acts in conjunction with another negative elongation factor DSIF/hSpt4-Spt5 to stall RNAPII at the early stages of transcription elongation. The repressive effect of NELF and DSIF can be relieved by the actions of several positive elongation factors, including RNAPII CTD kinase P-TEFb and chromatin-specific transcription elongation factor FACT (Yamaguchi et al. 1999; Wada et al. 2000). Genetic and cytological studies in several model systems, including yeast, fruit fly, and zebrafish, implicate these transcriptional elongation factors in various physiological processes such as development and heat shock response (Hartzog et al. 1998; Andrulis et al. 2000; Guo et al. 2000; Kaplan et al. 2000, 2003; Saunders et al. 2003). Nevertheless, the in vivo physiological roles of these transcription elongation factors in human cells are poorly understood.

In the current study, we demonstrate that COBRA1 (NELF-B) directly interacts with ERα and represses ERα-mediated gene activation. COBRA1 and the rest of the NELF complex are recruited to a number of endogenous ERα-responsive promoters in an estrogen-stimulated fashion. The promoter-bound NELF complex acts to stall RNAPII movement and attenuate ERα-dependent transcription. Thus, our work provides the first evidence for a physiological function of the human NELF complex. Furthermore, the estrogen-dependent regulation of the RNAPII movement represents a novel mechanism of hormonal gene regulation.

Results

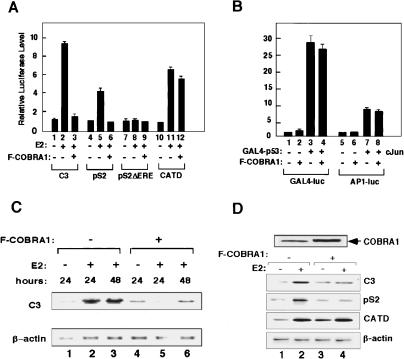

COBRA1 modulates estrogen-dependent transcriptional activation by ERα

In light of the multiple NR-binding motifs in COBRA1 (Ye et al. 2001), we used the luciferase reporter assay to assess the effect of COBRA1 on the estrogen-dependent activation of several ERα-responsive promoters, that is, complementation 3 (C3), pS2, and cathepsin D (CATD; Berry et al. 1989; Augereau et al. 1994; Norris et al. 1996). As shown in Figure 1A, ligand-dependent activation of the C3 and pS2 promoters by ERα was significantly repressed by the ectopically expressed COBRA1 (Fig. 1A, cf. lanes 2 and 3 for C3, cf. lanes 5 and 6 for pS2). Mutations of the EREs at the pS2 promoter abolished both the ligand-dependent gene activation and COBRA1-mediated repression (Fig. 1A, lanes 7–9). A similar repressive effect of COBRA1 on ERα-mediated transcription was also observed in HEK293T, MCF7, and COS7 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1; data not shown). COBRA1 did not inhibit transcriptional activation by other transcription factors such as GAL4-p53 and c-Jun (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the COBRA1-mediated transcriptional repression was not due to promoter squelching. Furthermore, COBRA1 did not inhibit ligand-dependent transcription from the ERα-responsive CATD promoter (Fig. 1A, lanes 10–12) or a synthetic ERE-tk promoter (Supplementary Fig. S1B). We infer from these data that additional cis- and trans-acting elements are required for the COBRA1-mediated repression.

Figure 1.

Ectopically expressed COBRA1 represses ligand-dependent transcriptional activation by ERα. (A) COBRA1 represses transcription from the luciferase-linked C3 and pS2 promoters, but not the CATD promoter. T47D cells were transfected with 0.5 μg COBRA1 and 0.5 μg of various luciferase reporter plasmids in the presence or absence of 10 nM E2. (B) COBRA1 does not affect transcription from ERα-unresponsive promoters. GAL4-p53 and c-Jun were cotransfected with a GAL4- or AP1-responsive luciferase reporter construct, respectively, in the presence or absence of Flag-COBRA1. (C) Northern hybridization indicates the impact of ectopic COBRA1 on the transcription of the endogenous C3 gene in T47D cells. Stably transfected T47D clones harboring either the pcDNA3 empty vector or Flag-COBRA1-expressing plasmid were treated with either ethanol or E2 for the indicated periods of time and harvested for RNA extraction. (D) RT–PCR analysis of the COBRA1 effect on the transcription of various ER-responsive genes. Pools of T47D cells stably transfected with either empty or COBRA1-expressing retroviral vectors were treated with ethanol or E2 (10 nM) for 24 h. RT–PCR was conducted on the total RNA to assess the transcription level of three ERα-responsive genes. In both C and D, β-Actin was used as an internal control. Also shown on the top of the panel is an anti-COBRA1 immunoblot indicating the total level of COBRA1 in the control and Flag-COBRA1-expressing cells.

To corroborate the finding of the luciferase reporter assay, we examined the effect of COBRA1 on the expression of endogenous ERα-responsive genes. Northern analysis showed that ligand-dependent activation of the C3 gene was obliterated by the ectopic COBRA1 (Fig. 1C, top, cf. lanes 1–3 and 4–6). We also used RT–PCR method to compare the effect of COBRA1 on three endogenous ERα-responsive genes (C3, pS2, and CATD). T47D cells were infected with retroviruses that expressed moderate levels of ectopic COBRA1 (Fig. 1D, top). As expected, transcription of all three ERα-responsive genes examined in the control cells was stimulated following the E2 treatment (Fig. 1D, cf. lanes 1 and 2). Consistent with the findings from the reporter assay, COBRA1 abolished ligand-dependent transcription of the C3 and pS2 genes, but not that of CATD (Fig. 1D, cf. lanes 2 and 4).

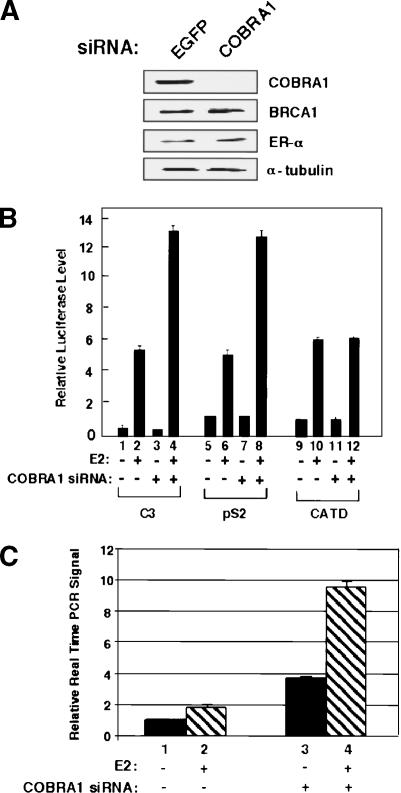

To investigate the role of endogenous COBRA1 in ERα-mediated gene activation, we established T47D derivatives with stably integrated small interfering RNA (siRNA)-expressing retroviruses. As shown in Figure 2A, expression of the COBRA1-specific siRNA resulted in a substantial reduction of the endogenous COBRA1 protein. Compared with the control cells, COBRA1 knockdown cells supported a significantly higher level of ligand-dependent transcription from the C3 and pS2, but not CATD promoters (Fig. 2B). In addition, real-time PCR analysis of the native pS2 and C3 gene expression shows that COBRA1 knockdown results in a significant increase in transcription from these ERα-responsive genes (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Fig. S6). Taken together, the functional study clearly indicates that COBRA1 acts as a corepressor to modulate ERα function at a subset of ERα-responsive genes.

Figure 2.

Reduction of endogenous COBRA1 in T47D cells enhances gene activation at a subset of ERα-responsive promoters. (A) Immunoblots with various antibodies indicating the specific knockdown effect of the COBRA1 siRNA on the endogenous COBRA1 protein level. Quantitative immunoblotting indicates ∼90% reduction of the COBRA1 protein in the knockdown cells. (B) Luciferase reporter assays in the control (EGFP siRNA) and COBRA1 siRNA-expressing cells, using three ERα-responsive promoters. (C) Real-time PCR determining the pS2 transcript levels in the control and COBRA1 knockdown cells. Results are averages of triplicates that are normalized against the transcript levels of β-actin.

Given the physical interaction between COBRA1 and BRCA1 and the reported corepressor function of BRCA1 in ERα-responsive transcription (Fan et al. 1999, 2001; Zheng et al. 2001), we also tested the dependence of COBRA1 on BRCA1 for transcriptional repression. As shown in Supplementary Figure S2A, COBRA1 effectively repressed the ligand-dependent transcriptional activation in a BRCA1-deficient cell line (HCC1937), indicating that wild-type BRCA1 was not required for the repressive effect of COBRA1. To explore any functional relationship of the two endogenous proteins in hormonal gene regulation, we established stable siRNA knockdown cells that had reduced levels of endogenous BRCA1, COBRA1, or both. In comparison with the COBRA1 knockdown, BRCA1 knockdown alone did not result in any substantial elevation in the ligand-dependent luciferase expression of the C3 promoter (Supplementary Fig. S2B, cf. lanes 2 and 4 and 6). In the COBRA1 knockdown background, additional knockdown of BRCA1 modestly enhanced the expression of the reporter gene (Supplementary Fig. S2B, cf. lanes 6 and 8) from the C3 promoter, the molecular basis for which awaits further investigation.

COBRA1 acts as part of the NELF complex to repress ligand-dependent transcription

During the course of our functional characterization of COBRA1, an independent biochemical study showed that COBRA1 is an integral component of the four-subunit NELF complex, which is involved in inhibiting RNAPII-dependent transcription elongation (Narita et al. 2003). We were able to confirm the in vivo interaction between COBRA1 and another subunit of NELF (NELF-E) in T47D cells (Supplementary Fig. S3). To examine the requirement of the NELF subunits for the COBRA1-mediated repression, we used the siRNA approach to knock down the endogenous NELF-E in T47D cells (Fig. 3A). Reduction of the endogenous NELF-E enhanced ligand-dependent transcription from the C3 (Fig. 3A, lanes 1–4) and pS2 (Fig. 3A, lanes 5–8), but not CATD promoter (Fig. 3A, lanes 9–12), thus mirroring the finding with the COBRA1 knockdown cells (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the NELF-E knockdown also resulted in increased ligand-dependent transcription of the endogenous pS2 gene (Fig. 3C, cf. lanes 2 and 4). The fact that siRNA knockdown targeted at two different NELF subunits leads to the same outcome in ERα-responsive transcription strongly suggests that NELF acts as a functional entity to modulate hormonal gene expression.

Figure 3.

COBRA1-mediated transcriptional repression requires the other NELF subunits. (A) Immunoblots of the endogenous NELF-E, β-actin, and α-tubulin in the control and NELF-E knockdown cells. (B) Luciferase reporter assay using three ERα-responsive promoters in the control and NELF-E knockdown cells. (C) Real-time PCR determining the pS2 transcript levels in the control and NELF-E knockdown cells. Results are normalized against the transcript levels of β-actin. (D) The effect of ectopic COBRA1 on the C3-luciferase activity in the control (lanes 1–6) and NELF-E knockdown cells (lanes 7–12). Also shown on the right is an anti-Flag immunoblot, indicating the levels of ectopic COBRA1 in the + and ++ samples.

To ascertain the physiological relevance of the finding using ectopically expressed COBRA1 as shown in Figure 1, we repeated the luciferase reporter assay in the control and NELF-E knockdown cells. As expected, Flag-COBRA1 repressed ligand-dependent transcription in the control cells (Fig. 3D, lanes 1–6). In contrast, when the endogenous NELF-E was reduced, comparable levels of the ectopically expressed COBRA1 no longer repressed ERα-mediated transcription (Fig. 3D, lanes 7–12). This result further substantiates the notion that COBRA1-mediated repression depends on the presence of other NELF subunits, thus providing the first in vivo evidence for a role of human NELF in gene-specific transcription regulation.

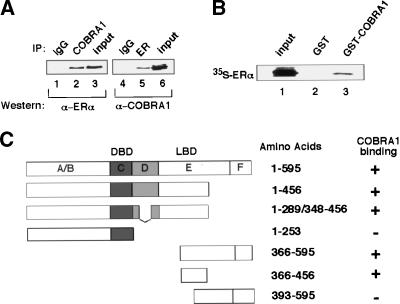

COBRA1 interacts with ERα in vivo and in vitro

To explore the molecular basis for the gene-specific effect of COBRA1, we examined a possible physical interaction between COBRA1 and ERα by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) of lysates from the ERα-positive MCF7 breast cancer cells. As shown in Figure 4A, endogenous ERα was present in the anti-COBRA1 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 4A, lanes 1–3). Likewise, endogenous COBRA1 was also detected in the reciprocal anti-ERα IP (Fig. 4A, lanes 4–6), thus demonstrating an in vivo association between the two proteins. To evaluate the COBRA1/ERα interaction in a more direct manner, a glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay was carried out. As shown in Figure 4B, GST-COBRA1 was able to pull down the 35S-labeled in vitro translated ERα. Further domain-mapping analysis of the ERα–COBRA1 interaction indicated that COBRA1 interacted with the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of ERα (Fig. 4C), a common region targeted by other coregulators of ERα (Glass and Rosenfeld 2000; McKenna and O'Malley 2002).

Figure 4.

COBRA1 interacts with ERα in vivo and in vitro. (A) Interaction between the endogenous COBRA1 and ERα. Nuclear lysates of breast cancer cells (MCF7) were immunoprecipitated with an anti-ERα or anti-COBRA1 antibody. The immunoprecipitates were subsequently probed with anti-COBRA1 or anti-ERα antibody. (Lanes 1,4) Purified rabbit or mouse IgG was used as a negative control. (B) GST pull-down assay for detecting the in vitro interaction between GST-COBRA1 and in vitro translated ERα. (C) Diagram indicating the affinity of various ERα constructs for COBRA1. Results were obtained from both co-IP and GST pulldown assays.

Ligand-stimulated recruitment of the NELF complex to native ERα-responsive promoters

The physical association between ERα and COBRA1 suggests a potential role of ERα in recruiting the NELF complex via COBRA1 to the ERα-responsive promoters. To directly test this possibility, we first conducted a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiment in ERα-deficient HEK293T cells that were cotransfected with ERα and Flag-COBRA1 expression vectors. As shown in Supplementary Figure S4A, Flag-COBRA1 was present at the native C3 and pS2 promoters only when ERα was ectopically expressed (Supplementary Fig. S4A, cf. the Flag signals in lanes 4 and 8). Interestingly, although a low level of Flag-COBRA1 was associated with the promoter prior to the E2 addition, recruitment of the tagged protein was greatly stimulated upon the ligand treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4A, cf. lanes 7 and 8). Moreover, loading of COBRA1 does not seem to affect ERα association with the same promoters (Supplementary Fig. S4A, cf. the ERα signals in lanes 6 and 8). This is consistent with the in vitro observation that recombinant COBRA1 protein does not prevent ERα from binding to its cognate DNA-binding site (data not shown).

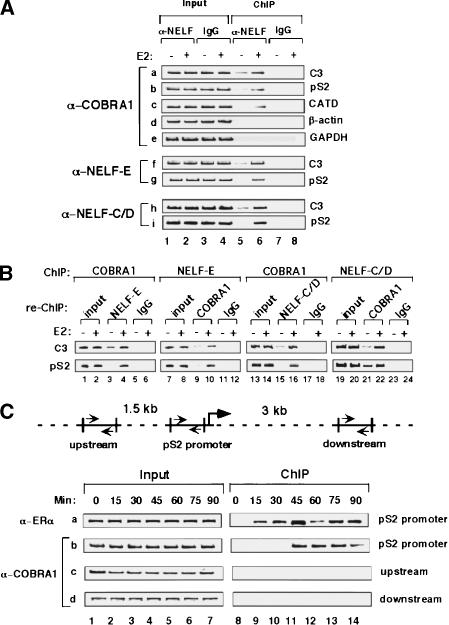

To investigate the in vivo association of the endogenous NELF complex with native promoters, we conducted ChIP in T47D cells by using antibodies raised against various NELF subunits (Fig. 5). The results showed that the endogenous COBRA1 was recruited in a ligand-stimulated fashion to the ERα-responsive promoters C3, pS2, and CATD (Fig. 5A, rows a–c), but not the promoters of two housekeeping genes (β-actin and GAPDH; Fig. 5A, rows d,e). Importantly, significant amounts of NELF-C/D and NELF-E were also associated with the C3 and pS2 promoters upon estrogen treatment (Fig. 5A, rows f–i), consistent with a joint action of the NELF subunits in modulating hormonal gene expression. To verify that COBRA1 and the other NELF subunits were concomitantly present at the same promoters, we also carried out ChIP and re-ChIP with various combinations of the anti-COBRA1, NELF-E, and NELF-C/D antibodies (Fig. 5B). The experiment unequivocally demonstrates that different NELF subunits are simultaneously associated with the same C3 and pS2 promoter-containing genomic fragments.

Figure 5.

Loading of endogenous NELF subunits at ERα-responsive promoters in a ligand-stimulated manner. (A) Ligand-stimulated recruitment of COBRA1, NELF-C/D, and NELF-E. T47D cells were treated with either ethanol or 10 nM E2 and subsequently cross-linked with formaldehyde. The cell lysates were used for the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay with anti-COBRA1 (rows a–e), anti-NELF-E (rows f,g), or anti-NELF-C/D (rows h,i) antibody. DNA fragments corresponding to various promoter regions (indicated on right) were amplified by PCR from input (lanes 1–4) and ChIP samples (lanes 5–8). (B) Simultaneous recruitment of COBRA1, NELF-E, and NELF-C/D to the C3 and pS2 promoters. Cross-linked T47D cell lysates were precipitated with the indicated antibody. The immunoprecipitates were re-ChIPed with either IgG or the antibody against one of the other NELF subunits. (C) Time course study of the in vivo association of endogenous ERα or COBRA1 with the pS2 promoter region. T47D cells were harvested at various periods of time after the ligand treatment. ChIP analysis was conducted by using anti-ERα and COBRA1 antibodies. Also shown is a diagram of the pS2 gene that indicates the relative positions of the primers used in the ChIP assay in this study.

To gain more insight into the ligand-stimulated recruitment of COBRA1, a time course ChIP analysis was performed to compare the kinetics of the ligand-stimulated loading of endogenous ERα and COBRA1 at the pS2 promoter (Fig. 5C). Although a significant amount of ERα was present at the promoter shortly after the addition of E2 (15 min; Fig. 5C, row a), no major amount of COBRA1 was detected at the same locus until 45 min after the ligand treatment (Fig. 5C, row b). Distinct from the cyclic pattern of ERα loading as previously reported (Fig. 5C, row a; Shao et al. 2002), the signal of COBRA1 at the promoter was relatively constant until later time points (Fig. 5C, row b). Of note, no COBRA1 was detected at regions several kilobases upstream or downstream of the promoter (Fig. 5C, rows c,d), suggesting that chromosomal association of COBRA1 was restricted to the promoter proximal region. A similar pattern of COBRA1 recruitment was observed at the C3 promoter (data not shown).

COBRA1 prevents RNAPII from leaving the promoter-proximal region

As shown above, a moderate expression of Flag-COBRA1 repressed ligand-dependent transcription from a subset of ER-responsive promoters (Fig. 1). Importantly, the COBRA1-mediated repression depended upon the function of the other NELF subunits (Fig. 3). Furthermore, ectopic expression of COBRA1 resulted in more promoter-bound NELF-E (Supplementary Fig. S4B, cf. lanes 5,6 and 7,8), suggesting that the COBRA1 level may be a rate-limiting factor for NELF function in T47D cells. Therefore, we used the Flag-COBRA1-expressing cells in the ChIP assay to determine the NELF-regulated step during ERα-mediated transcription activation. In particular, we examined the impact of the ectopically expressed COBRA1 on the dynamic association of ERα, coactivator p300, RNAPII with the ERα-responsive promoters (Fig. 6).

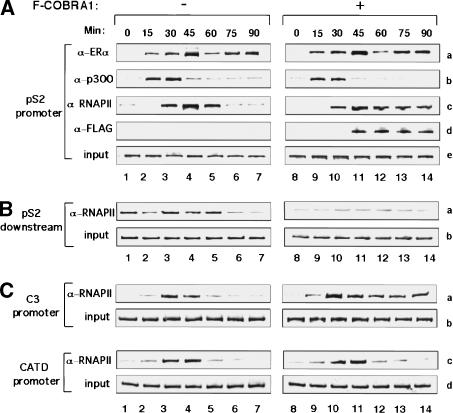

Figure 6.

Ectopic expression of COBRA1 results in stalled RNAPII at the promoter-proximal region of the ERα-responsive promoters. (A) Occupancy by ERα, p300, RNAPII, and Flag-COBRA1 at the pS2 promoter at 15-min time intervals after the addition of E2 in either the empty vector (lanes 1–7) or Flag-COBRA1 (lanes 8–14) retroviral stable cell lines. (B) Time course of RNAP II occupancy ∼3 kb downstream of the pS2 promoter in the control and Flag-COBRA1-expressing cell lines. (C) Time course of RNAP II occupancy at the C3 and CATD promoters in the control and Flag-COBRA1-expressing cell lines.

Consistent with the published results (Shang et al. 2000; Shao et al. 2002; Metivier et al. 2003), ERα and p300 in the control cells were recruited to the pS2 promoter shortly after the ligand treatment (15 min; Fig. 6A, rows a,b), which was followed by recruitment of RNAPII (30-min; Fig. 6A, row c). Similar to the endogenous COBRA1 (Fig. 5C, row b), the ectopically expressed Flag-COBRA1 was recruited to the promoter ∼45 min after the recruitment of ERα (Fig. 6A, row d). Once becoming promoter-bound, both the ectopic and endogenous COBRA1 were retained during the time course analyzed (cf. Figs. 5C and 6A).

When loading of ERα, p300, and RNAPII was compared between the control and COBRA1-overexpressing cells, we found that Flag-COBRA1 did not significantly affect the intensity of the ERα- and p300-dependent signals (Fig. 6A, rows a,b, cf. lanes 1–7 and 8–14). In stark contrast, COBRA1 caused a significant change in the pattern of RNAPII loading (Fig. 6A, row c). In particular, although RNAPII was dissociated from the promoter at the 75- and 90-min time points in the control cells (Fig. 6A, lanes 6,7), a relatively high level of promoter-bound RNAPII was sustained at these later time points in the Flag-COBRA1-expressing cells (Fig. 6A, lanes 13,14). The accumulation of RNAPII at the promoter region could result from recruitment of more polymerase molecules to the promoter. Alternatively, it could be due to pausing of the promoter-bound polymerase at the promoter-proximal region. To distinguish these two possibilities, we examined the association of RNAPII within the pS2 gene that is distal to the transcription initiation site. As shown in Figure 6B, significantly less RNAPII signal was detected at the distal site in the Flag-COBRA1-expressing cells than the control cells (Fig. 6B, row a, cf. lanes 1–7 and 8–14), strongly suggesting that COBRA1 prevented RNAPII from proceeding to the downstream region. A similar effect of COBRA1 on RNAPII was also observed at the promoter-proximal region of the C3 promoter (Fig. 6C, row a, cf. lanes 1–7 and 8–14). In contrast, the dynamics of RNAPII loading at the COBRA1-refractory CATD promoter was not affected (Fig. 6C, row c). Thus, the differential effects of COBRA1 on the RNAPII movement at these promoters correlate well with their responsiveness to NELF-mediated repression.

NELF is involved in inhibition of estrogen-dependent growth of breast cancer cells

The ERα/estrogen action plays a key role in mammary gland morphogenesis and breast cancer development. Given the repressive effect of NELF on ligand-dependent transcriptional activation by ERα, it is conceivable that it may also negatively impact the estrogen-dependent growth of breast cells. Indeed, when cultured in the conventional two-dimensional tissue culture systems, stable T47D cell clones that ectopically expressed COBRA1 displayed reduced rates of proliferation in comparison with the control cells harboring an empty expression vector (Supplementary Fig. S5A). To explore the potential role of the endogenous NELF complex on the ligand-dependent cell growth, we assessed the growth phenotype of COBRA1 and NELF-E siRNA-knockdown T47D cells in a three-dimensional tissue culture system (Bissell and Radisky 2001). Compared to the conventional two-dimensional tissue culture system, the Matrigel-supported three-dimensional system is advantageous in that it mimics the stromal environment that surrounds normal and cancerous breast epithelial cells in vivo (Jacks and Weinberg 2002). In the absence of exogenous estrogen, neither the control nor the NELF knockdown cells displayed robust growth (Fig. 7A, left), suggesting that reduction of the endogenous NELF proteins did not override the dependence on estrogen for T47D proliferation. Interestingly, when estrogen was included in the growth medium, the COBRA1 and NELF-E knockdown cells developed into larger irregular cell clumps than those observed in the control cells (Fig. 7A, right). In addition, when cultured in a two-dimensional culture system and in the presence of E2, the COBRA1 knockdown cells had an accelerated proliferation rate compared with the control cells (Supplementary Fig. S5B). Thus, the available data support a physiological role of NELF in restricting the ligand-dependent growth of breast epithelial cells via its corepressor function in the hormonal gene regulation.

Figure 7.

NELF in breast cancer cell lines and normal breast tissues. (A) Control, COBRA1, and NELF-E siRNA knockdown cells were grown in the Matrigel-containing three-dimensional tissue culture system in the presence or absence of E2 (10 nM). After 3 wk of growth incubation, the images were observed under phase microscopy with a 10× objective. (B) COBRA is preferentially expressed in the luminal epithelial cells of the mammary gland. Immunostaining of normal mammary ducts for COBRA1 (right) and ERα (center). The exclusive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) in myoepithelial cells is shown as a control (left). The brown color indicates the presence of protein. The locations of luminal epithelial (L) and myoepithelial cells (M) are also indicated.

In addition to the tissue culture study, we also examined expression of COBRA1 in normal human mammary ducts by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 7B). The epithelial cells of the mammary gland consist of two layers: luminal epithelial cells and basal myoepithelial cells. In keeping with the long-standing observation (Ronnov-Jessen et al. 1996), ERα is exclusively expressed in a fraction of luminal epithelial cells (Fig. 7B, center), whereas smooth muscle actin (SMA) is only expressed in myoepithelial cells (Fig. 7B, left). Interestingly, COBRA1 was predominantly expressed in the nuclei of luminal epithelial cells, whereas much less COBRA1 was detected in myoepithelial cells (right). The coexpression of COBRA1 and ERα in the same subtype of mammary epithelial cells in which most breast tumors are thought to originate is consistent with a potential functional consequence of the COBRA1–ERα interaction in mammary gland development and tumorigenesis.

Discussion

The current work provides the first evidence for a physiological role of the human NELF complex in attenuating ERα-responsive gene activation and estrogen-dependent proliferation of breast cancer cells. First, we show by both ectopic expression and siRNA knockdown approaches that COBRA1 and the other NELF subunits repress ERα-mediated transcription. Second, COBRA1 binds to ERα and is recruited to the endogenous ERα-responsive promoters in a ligand-stimulated manner. Third, the simultaneous recruitment and functional interdependence of different NELF subunits strongly suggest that NELF acts as a functional entity in modulating hormonal gene expression. Fourth, the promoter-specific pausing of RNAPII in vivo is in agreement with the in vitro biochemical properties of the NELF complex. Last but not least, results from the cell growth study point to a possible physiological consequence of NELF-mediated modulation of the ERα-responsive transcription in cancer development.

At surface value, it may seem counter-intuitive that the transcriptionally active, agonist-bound ERα would recruit a corepressor that in turn attenuates gene expression by impeding RNAPII movement. However, it is firmly established that hormone-responsive gene expression is a readily reversible process, the duration and magnitude of which have to be tightly controlled by combinatorial actions of functionally distinct coregulators in response to physiological fluctuations in signaling. Furthermore, emerging evidence indicates that several distinct mechanisms exist to attenuate the ligand-dependent response. For example, ligand-dependent corepressors may recruit histone deacetylases (HDACs) to antagonize the actions of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and thus reduce chromatin accessibility to the transcriptional machinery (Mazumdar et al. 2000; Zheng et al. 2001; Fernandes et al. 2003). In addition, upon hormone withdrawal, the transcriptional regulatory complexes may be dissembled through the actions of molecular chaperones (Freeman and Yamamoto 2002). Recent work also indicates that gene activation by ERα may be coupled to its degradation through the proteasomal pathway (Lonard et al. 2000; Wijayaratne and McDonnell 2001). The COBRA1-mediated stalling of RNAPII may represent a novel mechanism of attenuating hormone-responsive gene expression. In light of the transient and reversible nature of hormonal gene activation, the ligand-stimulated recruitment of NELF may be part of a self-imposed mechanism used by ERα to ensure a temporal and gene-specific modulation of hormonal response. It is also conceivable that NELF, which is recruited to the actively transcribing ERα-responsive promoters, may play an additional role in coordinating transcription with other posttranscriptional processes (Orphanides and Reinberg 2000; Bentley 2002; Maniatis and Reed 2002).

NELF was biochemically identified based upon its ability to stall RNAPII movement on a DNA template (Yamaguchi et al. 1999). Although the resolution of the ChIP assay does not allow us to pinpoint the exact location at which NELF dissociates from the affected genes, neither COBRA1 nor NELF-E-dependent signals were detected at various downstream positions within the C3 and pS2 genes (Fig. 5C; data not shown). Furthermore, quantitation of the unspliced C3 transcripts indicates a similar effect of COBRA1 siRNA knockdown on the abundance of the transcripts at the 5′ and 3′ regions of the ERα-responsive gene, which are >40 kb apart (Supplementary Fig. S6). Therefore, the in vivo work is consistent with the notion that NELF may act in the early phase of transcription elongation. Consistent with our finding, a recent study of the Drosophila NELF homologs indicated that they were also associated with the promoter-proximal region of the hsp70 promoter and were involved in polymerase pausing at the proximal region (Wu et al. 2003). Interestingly, Drosophila NELF is dissociated from the hsp70 promoter following heat shock, which is in contrast to the enhanced recruitment of human NELF concomitant with ligand-dependent gene activation. In the latter case, the presence of a relatively large amount of NELF at the ERα-responsive promoter following estrogen treatment apparently does not obliterate the overall level of ligand-dependent transcription. Thus, although Drosophila NELF may act as a “full brake” to completely halt the RNAPII movement prior to the heat shock signal, the “braking-while-driving” mode of regulation by human NELF may ensure a prompt transcriptional response to changes in hormone levels. Despite the distinct physiological outcomes of NELF actions in the two species, it is worth noting that heat shock and hormonal transcriptional responses are both rapid and reversible processes that may require special built-in mechanisms to constantly sense and respond to changes in temperature or hormone levels. In this regard, NELF may be dedicated to buffering cellular responses to various stress signals and hormone stimuli by modulating the RNAPII movement. Another possible role of NELF in ligand-dependent transcription may be to ensure the quality of mature transcripts by slowing down RNAPII movement and coordinating transcription with posttranscriptional events (Orphanides and Reinberg 2002). In this regard, it is worth noting that a recent biochemical study has indicated functional interactions between the RNA-capping enzyme and transcription elongation factors including NELF (Mandal et al. 2004).

In the real-time PCR analysis, we reproducibly detected a modest increase in the basal transcription of native pS2 gene in the COBRA1 knockdown cells (Fig. 2C). The basal transcription may be due to incomplete depletion of the endogenous E2 in the tissue culture medium, in which case the observed effect of COBRA1 could still be ligand-dependent. Alternatively, this may reflect a genuine COBRA1-mediated repression of ligand-independent transcription from the chromosomally embedded ERα-responsive promoter. Consistent with this possibility, we did detect low levels of NELF association with the ERα-responsive promoter fragments in the absence of exogenously added E2 in some of the ChIP experiments (e.g., Fig. 5A [lane 5], B [lane 21]; Supplementary Fig. S4A, lanes 5,7). Of note, several NR coregulators have been shown to regulate both ligand-dependent and-independent transcription, including ERα corepressor SAFB1 (Townson et al. 2004) and coactivator CoCoA (Kim et al. 2003).

The current work strongly suggests that agonist-bound ERα may have a dual function in ligand-dependent gene expression: it not only nucleates the assembly of an active transcription initiation complex but also recruits modulators such as NELF that act at later steps of the transcription process to curtail gene expression and/or coordinate transcription with other nuclear functions. However, our study also indicates that ERα-mediated recruitment of NELF is not sufficient for polymerase pausing and transcriptional repression. Although COBRA1 is recruited to all three ER-responsive promoters, it attenuates transcription from the C3 and pS2, but not CATD promoter. Furthermore, the promoter-bound NELF does not appear to dissociate from the chromosome in the same cyclic pattern as ERα, suggesting that, once loaded, NELF may not require ERα to maintain its association with the promoter regions. In light of the in vitro biochemical properties of the NELF complex, we postulate that the gene-specific action of the complex may be conferred by additional trans-acting factors and cis-acting regulatory sequences surrounding a specific gene. First of all, the exact ERE sequences and/or the presence of additional transcription factor-binding sites in the promoter region may influence the functional outcome of the NELF recruitment. In fact, a recent study has identified a negative upstream promoter element in the promoter of the A20 gene that mediates the transcriptional repression by DSIF (Ainbinder et al. 2004). Second, other transcription elongation complexes that either antagonize or cooperate with NELF may also modulate the impact of NELF at a given promoter. In this respect, it is of interest to note that several positive transcription elongation factors, including Spt6 and P-TEFb, have been reported to act as coactivators of steroid hormone receptors (Baniahmad et al. 1995; Zheng et al. 2001). Lastly, NELF's associations with RNA via NELF-E (Yamaguchi et al. 2002) and with RNAPII via the NELF-A (Narita et al. 2003) may also contribute to the promoter-specific action of the complex. These additional protein–protein and protein–RNA interactions could also influence the timing of NELF recruitment and aid in the maintenance of its association with the ERα-responsive promoters thereafter.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and plasmids

The following commercially available antibodies were used: αERα (Ab10; NeoMarkers) for IP, αERα (Novo Castra Laboratories), and for immunohistochemistry; α-SMA (BioGenex), αp300 (N-15), and αRNA Pol II (H-244; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and αFlag for IP (Sigma). To generate the rabbit polyclonal antibodies against COBRA1, NELF-C/D, and NELF-E, the full-length genes were cloned into pET19 (Novagen). His-tagged proteins were overexpressed and purified from Escherichia coli and used to immunize rabbits (Covance). The mouse monoclonal antibody for COBRA1 (F7E4) used in some ChIP experiments was also raised against the purified His-tagged full-length protein.

The following luciferase reporters were used: C3-luciferase (Norris et al. 1996), pS2-luciferase (Green and Chambon 1986), pS2ΔERE-luc (Tremblay et al. 1997), CATD-luciferase (Wu et al. 1998), Gal4-luciferase (Salghetti et al. 1999), and AP1-luciferase (Stratagene).

The following expression plasmids were used: Flag-COBRA1 (Ye et al. 2001), GAL4-p53 (Hu et al. 2000), cJun (Hu and Li 2002), pON260 (Li et al. 1991), HEGO-ERα (Green and Chambon 1986), ERα 1–456, and 1–289/348–456 (Ye et al. 2000). Fragments of ERα 1–253, 366–595, 366–456, and 393–595 were fused with an HA tag by cloning the corresponding PCR fragments into the pKH3 vector (Mattingly et al. 1994). GST-COBRA1 was constructed by subcloning COBRA1 into pGEX-KG. A retroviral plasmid that expresses Flag-COBRA1 was constructed by cloning the corresponding cDNA into pSRαNP (Briggs et al. 1997).

The following sequences were chosen to construct the siRNA expression vectors: COBRA1 (NELF-B), 5′-GACCTTCTGGAG AAGAGCT-3′; NELF-E, 5′-GGCATTGCTGGCTCTGAAG-3′; BRCA1, 5′-GGAAACCTGTCTCCACAAAG-3′; and EGFP, 5′-GAACGGCATCAAGGTGAAC-3′.

The oligonucleotides were inserted into the BglII and HindIII sites in pSUPER.retro vector (OligoEngine). The identities of the clones were verified by sequencing.

Cell lines

T47D, MCF7, and HEK293T were purchased from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's modified minimum essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum) and 100 μg/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. HCC1937 was purchased from ATCC and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% FBS, and 100 μg/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. To generate T47D derivatives used in the RT–PCR (Fig. 1D) and ChIP assays (Fig. 6), high-titer retroviral stocks for ectopic expression of COBRA1 were produced and used to infect T47D cells as previously described (Briggs et al. 1997). Following neomycin selection at 800 μg/mL for 2 wk, pooled cells were analyzed for expression of COBRA1. Flag-COBRA1-expressing T47D clones used in the Northern analysis (Fig. 1C) were generated by transfecting T47D cells with either pcDNA3 or its derivative harboring the COBRA1 gene, followed by neomycin selection and screening of individual drug-resistant clones for the ectopic expression of the COBRA1 transgene.

To generate the stable siRNA T47D cell lines, amphotrophic retroviral supernatants were produced by transfection of the pSUPER.retro vectors into Phoenix packaging cells. Viral supernatants were harvested 48–72 h posttransfection, and viral stock was passed through a 0.45-μm filter. For each infection, 3 × 104 T47D cells were plated in six-well tissue culture plates and incubated with viral stocks in a final volume of 5 mL. To enhance the efficiency of infection, cultures were centrifuged at 1500g for 4 h in the presence of 4 μg/mL Polybrene. Immediately following infection, the viral stock was replaced with fresh medium. Forty-eight hours later the medium was changed again into that containing either puromycin (10 μg/mL) or neomycin (800 μg/mL). Infected cells were selected with the corresponding antibiotics for 14 d. The stable siRNA cells lines were analyzed by immunoblotting for the protein expression.

Luciferase reporter assay

For ligand-dependent transcription assays, cells were seeded in NuncΔ 35-mm tissue culture plates and grown for 3 d in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% charcoal/dextrantreated fetal calf serum (HyClone). HEK293T cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), whereas the rest of the cell lines with either FuGene6 (Roche) or Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following day cells were treated with either ethanol or E2 at a final concentration of 10 nM. Typically, 0.5 μg luciferase reporter plasmid, 50 ng ERα, 125–500 ng COBRA1, and 0.5 μg pON260 β-galactosidase reporter plasmids were used. Luciferase values were normalized as described previously (Hu et al. 2000).

GST pull-down assay

The GST-COBRA1 protein was expressed and purified according to the manufacturer's instruction. ERα was produced in vitro in the TnT Reticulocyte Lysate system (Promega). The 35S-labeled ERα was mixed with 10 μg of GST derivatives bound to agarose beads in 0.5 mL of the binding buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40). The binding reaction was carried out overnight at 4°C and subsequently washed four times with the washing buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 8.0, 350 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40), 30 min each round. The proteins were eluted in 10 μL of 2× protein sample buffer and resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE. The gel was then dried and exposed to X-ray film overnight.

Co-IP

MCF7 cells grown in regular serum-containing DMEM medium were harvested, and nuclear extracts were prepared. One microgram extract was subjected to IP with 2 μg antibody as indicated. Samples were rotated for 2 h at 4°C, then 15 μL 50% Protein G-conjugated Sepharose slurry was added and rotated for an additional hour. The Sepharose beads were washed four times with a high-salt buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA). Proteins were eluted, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblotting with either α-ERα (D-12, Santa Cruz Biotech.) or α-COBRA1 polyclonal antibody.

Northern analysis and semiquantitative RT–PCR

For the Northern analysis shown in Figure 1C, mRNA was isolated from T47D derivatives by using the Oligotex mRNA kit (QIAGEN) per manufacturer's instructions. RNA was denatured in formaldehyde for 15 min at 55°C and then size-fractionated by electrophoresis in 1.0% agarose/formaldehyde gels. RNA was transferred to Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) by capillary action overnight. After transfer, the RNA was cross-linked to the membrane in an ultraviolet Stratalinker (Stratagene). The membrane was prehybridized for 4 h at 42°C in a solution of 50% formamide, 5× SSPE, 1× Denhardt's solution, 0.2% SDS, and 100 μg denatured salmon sperm DNA/mL. Hybridization was performed in the same solution overnight at 42°C by adding denatured 32P-labeled probe (∼1.0 × 106 cpm/mL). The membrane was washed in 2× SSC at room temperature and then with 1× SSC/0.1% SDS and 0.5× SSC/0.1% SDS at 42°C. The blots were exposed to the PhosphorImager for 2 d. For the semiquantitative RT–PCR experiment shown in Figure 1D, total RNA was isolated from T47D by using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacture's instructions. RNA was reverse-transcribed by using SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) or ImPrompII (Promega). The exact PCR conditions will be provided upon request.

ChIP

T47D cells were plated in 10-cm Nunc plates and grown for 4 d in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% charcoal-treated FBS. Cells were treated with either ethanol (vehicle) or 10 nM E2 for various times. Following treatment, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 8 min, then rinsed with ice-cold PBS, and collected into PBS containing protease inhibitors. Cells were washed in buffer I (0.25% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA at pH 8, 0.5 mM EGTA at pH 7.5, and 10 mM HEPES at pH 7.5). Cells were pelleted and washed again in buffer II (0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA at pH 8, 0.5 mM EGTA at pH 7.5, and 10 mM HEPES). Cells were pelleted and resuspended in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA at pH 8, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% NaDoc, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail). Cells were sonicated, followed by centrifugation to remove insoluble material. Supernatants were precleared for 2 h at 4°C with 2 μg sheared salmon sperm DNA and 20 μL of a 50% slurry of protein G-Sepharose. Approximately 3 × 106 cells were used per IP reaction. Antibodies were added to the precleared lysates, and the reaction was rotated overnight at 4°C. Samples were processed as described (Cheung et al. 2000). The re-ChIP experiments were conducted following the protocol as described by Shang et al. (2000). The sequences of the various primers used in semiquantitative PCR will be provided upon request. The results shown in Figures 5 and 6 are representatives of data from multiple ChIP experiments.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue blocks were obtained from the clinical archives of the Department of Pathology at the University of Virginia Health System, with institutional review board approval (HIC no. 10565). Four-micron histologic sections were cut, placed on charged glass slides (Superfrost Plus, Fisher Scientific), deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in a graded series of ethanol baths. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked in a 10-min incubation with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Antigen retrieval was used for estrogen receptor and COBRA1 immunohistochemistry, which was performed by immersing the sections in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heating in a 1200-W microwave oven at the highest power setting. Evaporated liquid was replenished at 5 min, then heated at high power for an additional 5 min. The slides were left in the buffer for an additional 10 min before being removed. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. The following antibodies were used: a mouse monoclonal antibody against ERα (Novo Castra Laboratories) at 1:80 dilution, a mouse monoclonal antibody to SMA (BioGenex) at 1:1600 dilution, and rabbit polyclonal antisera against COBRA1, 1:50 dilution. After washing in PBS, antibody binding was visualized by using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase technique (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories), followed by incubation with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride. The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (estrogen receptor and SMA) or methyl green (COBRA1). Negative controls consisted of paired histologic sections carried through the procedures, except with the elimination of the incubation with the primary antibodies.

Cell growth assays

For the two-dimensional tissue culture growth assay shown in S5A, cells were plated in regular 10% fetal bovine serum containing DMEM medium at the indicated density. For the two-dimensional growth assay shown in Supplementary Figure S5B, cells were seeded in DMEM with 10% charcoal-treated serum either with or without 10 nM exogenously added E2. Cells were harvested at various time points and subject to cell counting.

For the three-dimensional tissue culture system, the procedure was essentially as described by Debnath et al. (2003). Briefly, T47D cells were suspended in phenol red-free DMEM with 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum and 2% Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences). For some samples 10 nM E2 was included in the medium. Six thousand cells were seeded in each well of an eight-well chamber slide that contained a layer of 40 μL Matrigel. Cells were grown for 3 wk, and the Matrigel-containing medium was changed every 4 d. The images were documented periodically during the entire growth period.

Real-time PCR assay

The real-time PCR assay was conducted following the manufacturer's procedures (Applied Biosystems). Essentially, total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed by using the random primer method (ImPrompII from Promega). Real-time PCR was conducted by using the fluorescent dye SYBR Green and an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). For the analysis of mature RNA of the pS2 and C3 genes, exon-specific primers were designed by using the Primer Express Software program from ABI. The quantitation of unspliced transcripts accumulated at proximal and distal regions of the C3 gene (Supplementary Fig. S6) was conducted following the procedure as described previously (de la Mata et al. 2003). Primers were designed to cover the exon/intron junctions at the end of Exon 1 and beginning of Exon 40, respectively. RNA samples without the reverse transcriptase treatment were also used as a control to ensure that any minute amount of genomic DNA in the RNA preparations did not contribute significantly to the fluorescent signals from the PCR reactions. The sequences of the specific PCR primers will be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ian Macara and Scott Briggs for reagents; Peggy Shupnik, Pieter deHaseth, and Yanfen Hu for critical reading ofthe manuscript; Dr. Yongde Bao for assistance in real-time PCR assays; and members of the Li laboratory for stimulating discussion. S.E.A was supported by an National Institutes of Health postdoctoral training grant (1F32CA99359-01). Research support was from the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1214104.

References

- Ainbinder E., Amir-Zilberstein, L., Yamaguchi, Y., Handa, H., and Dikstein, R. 2004. Elongation inhibition by DRB sensitivity-inducing factor is regulated by the A20 promoter via a novel negative element and NF-κB. Mol. Biol. Cell. 24: 2444-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S. and Coombes, R.C. 2002. Endocrine-responsive breast cancer and strategies for combating resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2: 101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis E.D., Guzman, E., Doring, P., Werner, J., and Lis, J.T. 2000. High-resolution localization of Drosophila Spt5 and Spt6 at heat shock genes in vivo: Roles in promoter proximal pausing and transcription elongation. Genes & Dev. 14: 2635-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augereau P., Miralles, F., Cavailles, V., Gaudelet, C., Parker, M., and Rochefort, H. 1994. Characterization of the proximal estrogen-responsive element of human cathepsin D gene. Mol. Endocrinol. 8: 693-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baniahmad C., Nawaz, Z., Baniahmad, A., Gleeson, M.A., Tsai, M.J., and O'Malley, B.W. 1995. Enhancement of human estrogen receptor activity by SPT6: A potential coactivator. Mol. Endocrinol. 9: 34-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley D. 2002. The mRNA assembly line: Transcription and processing machines in the same factory. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14: 336-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M., Nunez, A.-M., and Chambon, P. 1989. Estrogen-responsive element of the human pS2 gene is an imperfectly palindromic sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 86: 1218-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell M.J. and Radisky, D. 2001. Putting tumors in context. Nat. Rev. Cancer 1: 46-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs S.D., Sharkey, M., Stevenson, M., and Smithgall, T.E. 1997. SH3-meidated HckTyrosine kinase activation and fibroblast transformation by the Nef protein of HIV-1. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 17899-17902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P., Tanner, K.G., Cheung, W.L., Sassone-Corsi, P., Denu, J.M., and Allis, C.D. 2000. Synergistic coupling of histone H3 phosphorylation and acetylation in response to epidermal growth factor stimulation. Mol. Cell 5: 905-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mata M., Alonso, C.R., Kadener, S., Fededa, J.P., Blaustein, M., Pelisch, F., Cramer, P., Bentley, D., and Kornblihtt, A.R. 2003. A slow RNA polymerase II affects alternative splicing in vivo. Mol. Cell 12: 525-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath J., Muthuswamy, S.K., and Brugge, J.S. 2003. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods 30: 256-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S., Wang, J., Yuan, R., Ma, Y., Meng, Q., Erdos, M.R., Pestell, R.G., Yuan, F., Auborn, K.J., Goldberg, I.D., et al. 1999. BRCA1 inhibition of estrogen receptor signaling in transfected cells. Science 284: 1354-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S., Ma, Y.X., Wang, C., Yuan, R.Q., Meng, Q., Wang, J.A., Erdos, M., Goldberg, I.D., Webb, P., Kushner, P.J., et al. 2001. Role of direct interaction in BRCA1 inhibition of estrogen receptor activity. Oncogene 20: 77-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes I., Bastien, Y., Wai, T., Nygard, K., Lin, R., Cormier, O., Lee, H.S., Eng, F., Bertos, N.R., Pelletier, N., et al. 2003. Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor corepressor LCoR functions by histone deacetylase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol. Cell 11: 139-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J.S., Henley, D.C., Ahamed, S., and Wimalasena, J. 2001. Estrogens and cell-cycle regulation in breast cancer. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 12: 320-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman B.C. and Yamamoto, K.G. 2002. Disassembly of transcriptional regulatory complexes by molecular chaperones. Science 296: 2232-2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass C.K. and Rosenfeld, M.G. 2000. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes & Dev. 14: 121-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S. and Chambon, P. 1986. A superfamily of potentially oncogenic hormone receptors. Nature 324: 615-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S., Yamaguchi, Y., Schilbach, S., Wada, T., Lee, J., Goddard, A., French, D., Handa, H., and Rosenthal, A. 2000. A regulator of transcriptional elongation controls vertebrate neuronal development. Nature 408: 366-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzog G.A., Wada, T., Handa, H., and Winston, F. 1998. Evidence that Spt4, Spt5, and Spt6 control transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes & Dev. 12: 357-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.-H. and Li., R 2002. JunB Potentiates function of BRCA1 activation domain 1(AD1) through a coiled-coil-mediated interaction. Genes & Dev. 16: 1509-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.-F., Miyake, T., Ye, Q., and Li, R. 2000. Characterization of a novel trans-activation domain of BRCA1 that functions in concert with the BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) domain. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 40910-40915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T. and Weinberg, R.A. 2002. Taking the study of cancer cell survival to a new dimension. Cell 111: 923-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan C.D., Morris, J.R., Wu, C.T., and Winston, F. 2000. Spt5 and Spt6 are associated with active transcription and have characteristics of general elongation factors in D. melanogaster. Genes & Dev. 14: 2623-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan C.D., Laprade, L., and Winston, F. 2003. Transcription elongation factors repress transcription initiation from cryptic sites. Science 301: 1096-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Li, H., and Stallcup, M.R. 2003. CoCoA, a nuclear receptor coactivator which acts through an N-terminal activation domain of p160 coactivators. Mol. Cell 12: 1537-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner P.J., Agard, D.A., Greene, G.L., Scanlan, T.S., Shiau, A.K., Uht, R.M., and Webb, P. 2000. Estrogen receptor pathways to AP-1. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 74: 311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Knight, J.D., Jackson, S.P., Tjian, R., and Botchan, M.R. 1991. Direct interaction between Sp1 and the BPV enhancer E2 protein mediates synergistic activation of transcription. Cell 65: 493-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard D.M., Nawaz, Z., Smith, C.L., and O'Malley, B.W. 2000. The 26S proteasome is required for estrogen receptor-α and coactivator turnover and for efficient estrogen receptor-α transactivation. Mol. Cell 5: 939-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S.S., Chu, C., Wada, T., Handa, H., Shatkin, A.J., and Reinberg, D. 2004. Functional interactions of RNA-capping enzyme with factors that positively and negatively regulate promoter escape by RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 7572-7577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T. and Reed, R. 2002. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature 416: 499-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly R.R., Sorisky, A., Brann, M.R., and Macara, I.G. 1994. Muscarinic receptors transform NIH 3T3 cells through a Ras-dependent signalling pathway inhibited by the Ras-GTPase-activating protein SH3 domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 7943-7952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar A., Wang, R.A., Mishra, S.K., Adam, L., Bagheri-Yarmand, R., Mandal, M., Vadlamudi, R.K., and Kumar, R. 2000. Transcriptional repression of oestrogen receptor by metastasis-associated protein 1 corepressor. Nat. Cell. Biol. 3: 30-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna N.J. and O'Malley, B.W. 2002. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell 108: 465-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R., Penot, G., Hubner, M.R., Reid, G., Brand, H., Kos, M., and Gannon, F. 2003. Estrogen receptor-a directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell 115: 751-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita T., Yamaguchi, Y., Yano, K., Sugimoto, S., Chanarat, S., Wada, T., Kim, D.K., Hasegawa, J., Omori, M., Inukai, N., et al. 2003. Human transcription elongation factor NELF: Identification of novel subunits and reconstitution of the functionally active complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 1863-1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S., Makela, S., Treuter, E., Tujague, M., Thomsen, J., Andersson, G., Enmark, E., Pattersson, K., Warner, M., and Gustafsson, J.A. 2001. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol. Rev. 81: 1535-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J.D., Fan, D., Wagner, B.L., and McDonnell, D.P. 1996. Identification of the sequences within the human complement 3 promoter required for estrogen responsiveness provides insight into the mechanism of tamoxifen mixed agonist activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 10: 1605-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphanides G. and Reinberg, D. 2000. RNA polymerase II elongation through chromatin. Nature 407: 471-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 2002. A unified theory of gene expression. Cell 108: 439-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson I. 2000. Estrogens in the causation of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers: Evidence and hypotheses from epidemiological findings. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 74: 357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnov-Jessen L., Petersen, O.W., and Bissell, M.J. 1996. Cellular changes involved in conversion of normal to malignant breast: Importance of the stromal reaction. Physiol. Rev. 76: 69-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salghetti S.E., Kim, S.Y., and Tansey, W.P. 1999. Destruction of Myc by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis: Cancer-associated and transforming mutations stabilize Myc. EMBO J. 18: 717-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders A., Werner, J., Andrulis, E.D., Nakayama, T., Hirose, S., Reinberg, D., and Lis, J.T. 2003. Tracking FACT and the RNA polymerase II elongation complex through chromatin in vivo. Science 301: 1094-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y., Hu, X., DiRenzo, J., Lazar, M.A., and Brown, M. 2000. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell 103: 843-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao W., Halachmi, S., and Brown, M. 2002. ERAP140, a conserved tissue-specific nuclear receptor coactivator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 3358-3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townson S.M., Kang, K., Lee, A.V., and Oesterreich, S. 2004. Structure-function analysis of the estrogen receptor α corepressor scaffold attachment factor-B1: Identification of a potent transcriptional repression domain. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 26074-26081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay G.B., Tremblay, A., Copeland, N.G., Gilbert, D.J., Jenkins, N.A., Labrie, F., and Giguere, V. 1997. Cloning, chromosomal localization, and functional analysis of the murine estrogen receptor β. Mol. Endocrinol. 11: 353-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T., Orphanides, G., Hasegawa, J., Kim, D.K., Shima, D., Yamaguchi, Y., Fukuda, A., Hisatake, K., and Handa, H. 2000. FACT relieves DSIF/NELF-mediated inhibition of transcriptional elongation and reveals functional differences between P-TEFb and TFIIH. Mol. Cell 5: 1067-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel N.L. and Zhang, Y. 1998. Ligand-independent activation of steroid hormone receptors. J. Mol. Med. 76: 469-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijayaratne A.L. and McDonnell, D.P. 2001. The human estrogen receptor α is a ubiquitinated protein whose stability is affected differentially by agonists, antagonists, and selective estrogen receptor modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 35684-35692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston F. 2001. Control of eukaryotic transcription elongation. Genome Biol. 2: 1006.1-1006.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.S., Saftig, P., Peters, C., and El-Deiry, W.S. 1998. Potential role for cathepsin D in p53-dependent tumor suppression and chemosensitivity. Oncogene 16: 2177-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-H., Yamaguchi, Y., Benjamin, L.R., Horvat-Gordon, M., Washinsky, J., Enerly, E., Larsson, J., Lambertsson, A., Handa, H., and Gilmour, D. 2003. NELF and DSIF cause promoter proximal pausing on the hsp70 promoter in Drosophila. Genes & Dev. 17: 1402-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Takagi, T., Wada, T., Yano, K., Furuya, A., Sugimoto, S., Hasegawa, J., and Handa, H. 1999. NELF, a multisubunit complex containing RD, cooperates with DSIF to repress RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell 97: 41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Inukai, N., Narita, T., Wada, T., and Handa, H. 2002. Evidence that negative elongation factor represses transcription elongation through binding to a DRB sensitivity-inducing factor/RNA polymerase II complex and RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 2918-2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q., Chung, L.W., Cinar, B., Li, S., and Zhau, H.E. 2000. Identification and characterization of estrogen receptor variants in prostate cancer cell lines. J. Steriod Biochem. Mol. Biol. 75: 21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q., Hu, Y.F., Zhong, H., Nye, A.C., Belmont, A.S., and Li, R. 2001. BRCA1-induced large-scale chromatin unfolding and allele-specific effects of cancer-predisposing mutations. J. Cell Biol. 155: 911-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Annab, L.A., Afshari, C.A., Lee, W.H., and Boyer, T.G. 2001. BRCA1 mediates ligand-independent transcriptional repression of the estrogen receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 9587-9592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorio D.A.R. and Bentley, D.L. 2001. Transcription elongation: The `Foggy' is lifting. Curr. Biol. 11: R114-R146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]