Abstract

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is an important advance for the treatment of end--stage heart failure (HF). About 15–50% of HF is complicated by atrial fibrillation (AF) and associated with worsened outcomes. Meta-analyses from observational studies suggest that patients with AF derive similar benefits to CRT as patients in sinus rhythm (SR). The presence of AF, however, may interfere with optimal delivery of CRT due to competition with biventricular (BiV) capture by conducted beats. Atrioventricular junction (AVJ) ablation with permanent pacing eliminates interference by conducted beats and provides complete BiV capture. Catheter ablation of AF is an alternative to antiarrhythmic drugs to maintain sinus rhythm in patients with AF and HF. Randomized trial comparing catheter ablation, AVJ ablation and pharmacologic therapy are needed.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) frequently coexists with heart failure (HF); the two conditions have been described as the twin epidemic of modern medicine.[1] The prevalence of AF is closely related to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. In approximate terms, the prevalence is 5% for NYHA functional class I, 10% to 25% for class II to III, and as high as 50% for class IV.[2,3] The presence of AF in patients with HF often heralds a much worse prognosis. As seen in the Framingham study, the risk of death approximately doubled in HF patients who experienced AF.[4]

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is an important device-based therapeutic modality for patients with advanced drug-refractory HF.[5,6] Current guidelines recommend CRT therapy for patients with NYHA Class III to IV HF with ejection fraction (EF) ≤ 35% and presence of ventricular dyssynchrony (QRS duration ≥ 120 msec). This is based on several clinical trials that have consistently demonstrated the efficacy of CRT in patients with clinical trials. These trials have essentially exclusively included patients in sinus rhythm. Whereas the prevalence of AF in patients with HF ranges from 25-50%, the percentage of patients with AF in clinical trials is very low (<1%).[7] Thus the data for efficacy of CRT in AF patients has been largely.obtained from nonrandomized studies that have included small number of AF patients.[6,7-9]

Several observational studies have provided data on the efficacy of CRT in this patient cohort. Leon et al. studied 20 patients with HF (EF≤ 35%, NYHA Class III /IV), prior atrioventricular junction (AVJ) ablation and RV pacing performed for permanent AF. There was significant improvement in NYHA class and EF, decrease in the number of hospitalizations and improved quality of life scores.[10] Molhoek et al. evaluated the clinical response and long-term survival of CRT in 60 patients with NYHA Class III/IV HF and decreased EF (< 35%), of whom 30 were in sinus rhythm and 30 had chronic AF.[11] The study showed that improvement in clinical parameters (NYHA class, exercise capacity, and quality of life score) was comparable between patients who had sinus rhythm and those who had AF. Of the 30 patients with AF,17 patients had AVJ ablation.

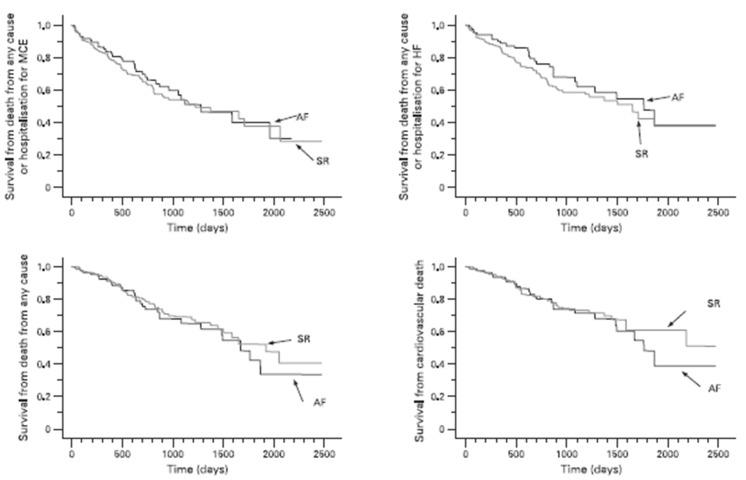

The MUSTIC (MUltisite STimulation in Cardiomyopathies) trial was a randomized cross-over study of 131 patients including 67 who were in sinus rhythm and 64 in AF.[12] The trial demonstrated similar improvement in the 6 minute walk test in Class III HF patients following CRT whether they were in sinus rhythm or in AF. Of the 64 AF patients, only 37 patients completed both crossover phases greatly limiting the impact of the results. An important criterion was that all patients in AF had a slow ventricular rate due to either spontaneous or induced AV block. This likely distinguished a subset of patients with AF that benefited from CRT due to consistent high degree of BiV capture. More recently, Khadjooi et al. presented results from a prospective observational study of 295 patients with HF and AF (permanent and paroxysmal) who were treated with CRT without AVJ ablation.[13] The primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for HF. Patients were followed up for almost 7 years. Overall, patients in AF and sinus rhythm derived similar benefits. There was improvement in NYHA Class, 6-min walk test and quality of life scores in both groups and evidence of echocardiographic remodeling ([Figure 1]).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of the time to the various clinical end-points in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and patients in sinus rhythm (SR). HF, Heart failure; MCE, major cardiovascular events. No significant group differences emerged with respect to any of the end-points.

Upadhyay et al. performed a meta-analysis of 5 prospective studies of1164 subjects comparing patients in SR and AF treated with CRT.[14] Both AF and SR patients benefited significantly from CRT. Mortality was not significantly different at 1 year. NYHA class improved similarly for both SR and AF patients; however SR patients showed greater relative improvement in the 6-min walk test. In addition, AF patients achieved a statistically significant improvement in EF. Thus patients with AF derived largely similar benefits from CRT as patients in SR.

Importance of AF in Patients Who Undergo CRT

The benefit of CRT is predicated on complete and consistent biventricular (BiV) capture. Several important concerns arise in patients with HF that receive CRT in the setting of AF that may prevent optimum delivery of CRT. There is lack of AV synchrony, and thus the inability to establish coordinated AV pacing; BiV capture is difficult to assure. Even at physiologic normal rates, consistent pacing and capture is difficult to achieve.[15] Fusion and pseudo-fusion beats resulting from an interaction between intrinsically conducted and paced beats may be responsible for ineffective pacing despite apparent delivery of CRT.[16,17] This is further exacerbated when patients with AF have intermittent or consistently accelerated ventricular rates.

CRT: Atrial Pacing Prevention Algorithms

A vicious cycle exists between AF and HF; thus interruption or prevention may be a worthwhile therapeutic strategy. CRT combined with a refined atrial tachyarrhythmia prevention pacing algorithm would appear to be an important addition in the management of AF. However, results from MASCOT (The Management of Atrial fibrillation Suppression in AF-HF COmorbidity Therapy) trial that randomized 394 patients with NYHA Class III/IV HF to the addition of atrial overdrive pacing to CRT did not show any benefit in the incidence of AF. It is likely that the advanced atrial remodeling in the setting of HF and AF may preclude benefit from atrial pacing algorithms.[18]

CRT: Ventricular Capture Pacing Algorithms

Irregular heart rate itself is associated with worsened cardiac function in patients with AF and HF.[16] Ventricular rate control has been considered to be an important component to optimal CRT delivery during rapid ventricular rates. Modern CRT devices employ algorithms designed to maximize ventricular pacing during potentially disruptive events such as rapidly conducted atrial arrhythmias. For Medtronic devices, the Ventricular Sense Response™ feature triggers pacing in one or both ventricles after each RV-sensed event. Medtronic’s Conducted AF Response™ resynchronizes conducted beats in AF up to a minimum R-R interval without increasing ventricular rate. Boston-Scientific’s Ventricular Rate Regularization™ algorithm is intended to restore resynchronization and ventricular regularity by pacing the ventricle during irregular conduction of AF.[19] It is unclear if these interventions provide any benefit.

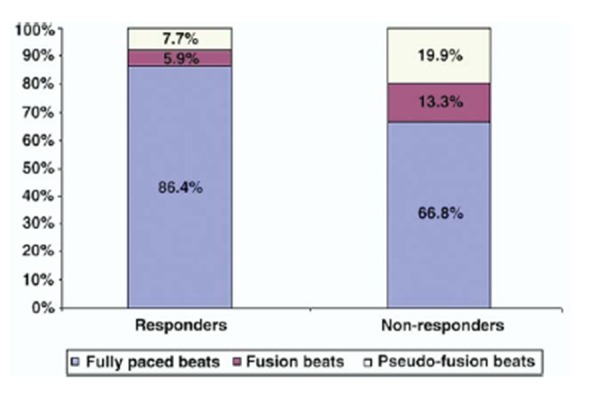

It is important to emphasize that the percentage of BiV pacing alone as recorded by the CRT device may be an ineffective surrogate of complete and consistent BiV capture. The presence of fusion and pseudo-fusion beats may be the cause for non-response to CRT therapy. This is true even if the pacing algorithms described above are deployed. To demonstrate this, we studied 19 patients with permanent AF who underwent CRT.[20] All patients received medical therapy with digoxin, β-blockers, and amiodarone for rate control, and device interrogation showed >90% BiV pacing. At a median of 12 months after device implant, patients were instructed to wear an ambulatory 12-Lead Holter for 24 hours. Effective pacing was defined by the presence of more than 90% fully paced beats with complete ventricular capture as confirmed in all 12 leads. In all CRT devices, device-specific special pacing algorithms were activated.

Despite advanced pacing algorithms and CRT device counters showing >90% pacing, in reality, only 47 % patients had effective pacing (>90% fully paced beats/24hrs). More than half of the remaining patients (56%) met criteria for ineffective pacing; in these patients, nearly 40% of pacing was accounted by fusion and pseudo-fusion ([Figure 2]). Only patients with effective pacing demonstrated response to CRT (≥ 1 NYHA improvement) and had evidence of reverse remodeling. These results indicate that despite the fact that CRT counters show a high degree of BiV pacing, complete BiV capture may still be less than optimal. Home Monitoring TM (Biotronik, Berlin, Germany) is a long distance telemetry system that provides automatic transmission of data stored in the pacemaker memory on daily basis. A study of 161 patients by Santini et al., employing this technology in patients with implanted devices, allowed early detection of AF in paced patients and allowed early intervention and optimization of medical treatment.[21] Thus in all patients with AF who receive CRT, close follow-up is essential to identify any episodes of atrial tachyarrhythmia that may elicit less that complete CRT delivery.

Figure 2. Responders had a higher percentage of fully paced beats than nonresponders (p = 0.03). Nonresponders had a significantly higher percentage of ineffective pacing because of a combination of fusion (p = 0.04) and pseudo-fusion (p = 0.02) beats [Adapted from Kamath et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53: 1050-1055].

Atrioventricular Junction Ablation

Destruction of the AVJ and placement of permanent pacemaker has been used in patients with AF with uncontrolled ventricular rates. However, in patients with AF who undergo CRT therapy, AVJ ablation is increasingly being viewed as a necessary adjunct to ensure adequate CRT delivery. The OPSITE trial compared 44 patients with right ventricle (RV) versus LV pacing after AVJ ablation in patients with permanent AF. Compared with RV pacing, LV pacing had greater improvement in EF and mitral regurgitation scores.[22] The Post AV Nodal Ablation evaluation (PAVE) study randomized 184 patients with chronic AF undergoing AV node ablation to BiV (n = 103) or a RV pacing system (n = 81). At 6 months post-ablation, patients treated with BiV pacing had significant improvement in 6-minute walk distance in comparison to patients receiving right ventricular pacing. There was decrease in EF in the RV paced group while EF remained stable in the BiV group.[23]

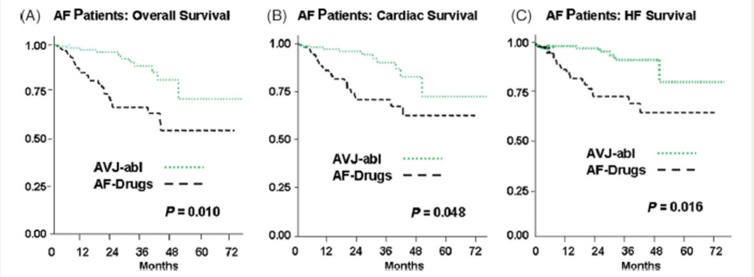

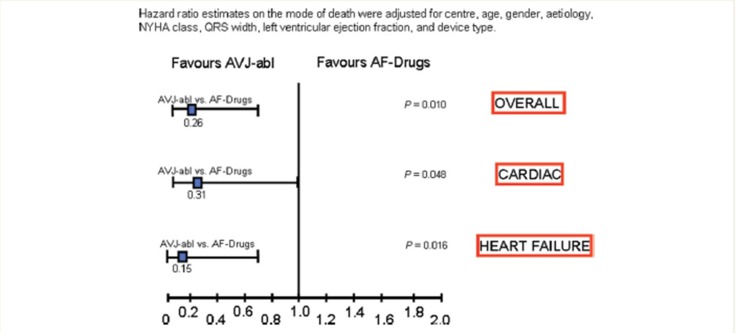

Gasparini et al. presented long-term data on 1285 consecutive patients with HF who underwent CRT device therapy. Of these, 1042 patients were in sinus rhythm and 243 patients had AF. All patients had close clinical follow-up. All-cause mortality and cardiac mortality was similar between the 2 groups.[24] When the cohort of patients with AF that underwent CRT was examined separately, it was the group that underwent AVJ-ablation that achieved maximum benefit ([Figures 3 and 4]). The group that underwent AVJ ablation had a 74% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality and 85% for HF mortality when compared to the group treated with AAD therapy. Ferreira et al. also conducted a retrospective analysis of 131 consecutive HF patients who underwent CRT implantation.[25] The patients in three groups were considered: sinus rhythm (n = 78), AF with AVJ ablation (n= 26), and AF without AVJ ablation (n = 27).

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall (A), cardiac (B), and heart failure (C) survival between AF pts who underwent atrio-ventricular junction ablation (AVJ-abl) and AF patients treated only with negative dromotropic drugs (AF-Drugs) [Adapted from Gasparini et al. Eur Heart J 2008: 29; 1644–1652]with respect to any of the end-points.

Figure 4. Hazard ratio estimates stratified according to cause of death between atrial fibrillation patients who underwent atrio-ventricular junction ablation (AVJ-abl) and patients treated with negative dromotropicdrugs (AF-Drugs) [Adapted from Gasparini et al. Eur Heart J 2008: 29; 1644–1652].

The primary outcomes were occurrence of cardiac death, hospitalization for HF, and improvement in NYHA class. There was a significant improvement in the NYHA class in all 3 groups. However, the proportion of responders was significantly lower in AF patients without AVJ ablation (52 vs. 79% in SR and 85% in AF with AVJ ablation). AF without AVJ ablation was independently associated with five-fold increase in mortality and six-fold risk of hospitalization for HF during the first 12 months. The outcomes of AF with AVJ ablation patients were similar to the outcomes of patients in sinus rhythm. The authors concluded that AF patients display similar survival as sinus rhythm patients provided that AVJ ablation is performed.

Although these data suggest that patients with AF and HF may do better with the ‛ablate and pace’ strategy, the concern of making patients pacemaker dependent is ever present. In addition, our recent data suggests that in patients with permanent AF and CRT, there may be spontaneous conversion to sinus rhythm during follow-up .[26] Gasparini et al. studied 330 HF patients with permanent AF that underwent CRT and were followed for up to 8 years.[27] A total of 10.3% of patients experienced spontaneous resumption of sinus rhythm (SRR) at median 4 months after CRT. End-diastolic diameter <65 mm [hazard ratios (HR) 4.03, p=0.008], post-CRT QRS <150 ms (HR 2.63, p=0.05), left atrial (LA) diameter <50 mm (HR 4.76, p=0.002), and AVJ ablation (HR 4.27, p=0.02) were independent predictors of SRR. Data from larger and randomized clinical trials will be needed before utilizing AVJ ablation as a standard practice since this would create a large number of pacemaker-dependent HF patients.

Catheter Ablation of AF

In patients with permanent AF who undergo CRT comwithout AVJ ablation, a few studies have suggested that cardioversion and aggressive rhythm control result in better clinical outcomes.[28,29] However, currently available antiarrhythmic drugs (AAD) are only partially effective in maintaining sinus rhythm and this is achieved at the cost of potential risk. In the AFFIRM trial, the use of AAD was associated with an almost 50% increase in mortality which offset the potential benefit of maintaining sinus rhythm.[30] Catheter ablation may offer another approach for achieving sinus rhythm in these patients.[31,32] Several clinical trials have demonstrated catheter ablation as a promising alternative. Chen et al. studied 94 patients with decreased ejection fraction (LVEF=36%) who underwent catheter ablation.[33] The control group was 283 patients who had normal EF. At 14 months of follow-up, there was a 5% improvement in EF and 73% of patients were free from AF recurrence in the decreased EF group. Hsu et al. studied 58 consecutive patients with HF and LVEF<45% who underwent catheter ablation for AF and com pared their outcomes to a matched control group without HF.[34] Sinus rhythm was achieved in 78% of patients with HF and in 84% of controls. In addition, patients with HF had significant improvements in EF, LV dimensions, exercise capacity and quality of life. Tondo et al. evaluated 40 patients with LV dysfunction with EF <40% and compared them to the 65 patients with normal ventricular function.[35] After a mean follow-up of 14 months, 87% of patients with impaired LV function and 92% of patients with normal ventricular function were in sinus rhythm, with or without AAD therapy. A significant improvement in LVEF was seen in patients with HF (33% to 47%).

More recently, we evaluated 15 pts with AF and symptomatic LV dysfunction (EF <= 45%) referred for ablation.[36] These pts were compared to a matched cohort treated medically for AF with LV dysfunction. Baseline EF in the study group was 37% and for the controls was 34%. The groups were similar in all respects. During 16 months following ablation, EF improved to 50%±13% along with significant improvement in the NYHA class. In the medically treated group, no improvement in EF (36 ± 12%) or NYHA class was seen. Thus, compared to pharmacologic therapy, ablation significantly improved LV function and NYHA class in pts with AF and symptomatic LV dysfunction.

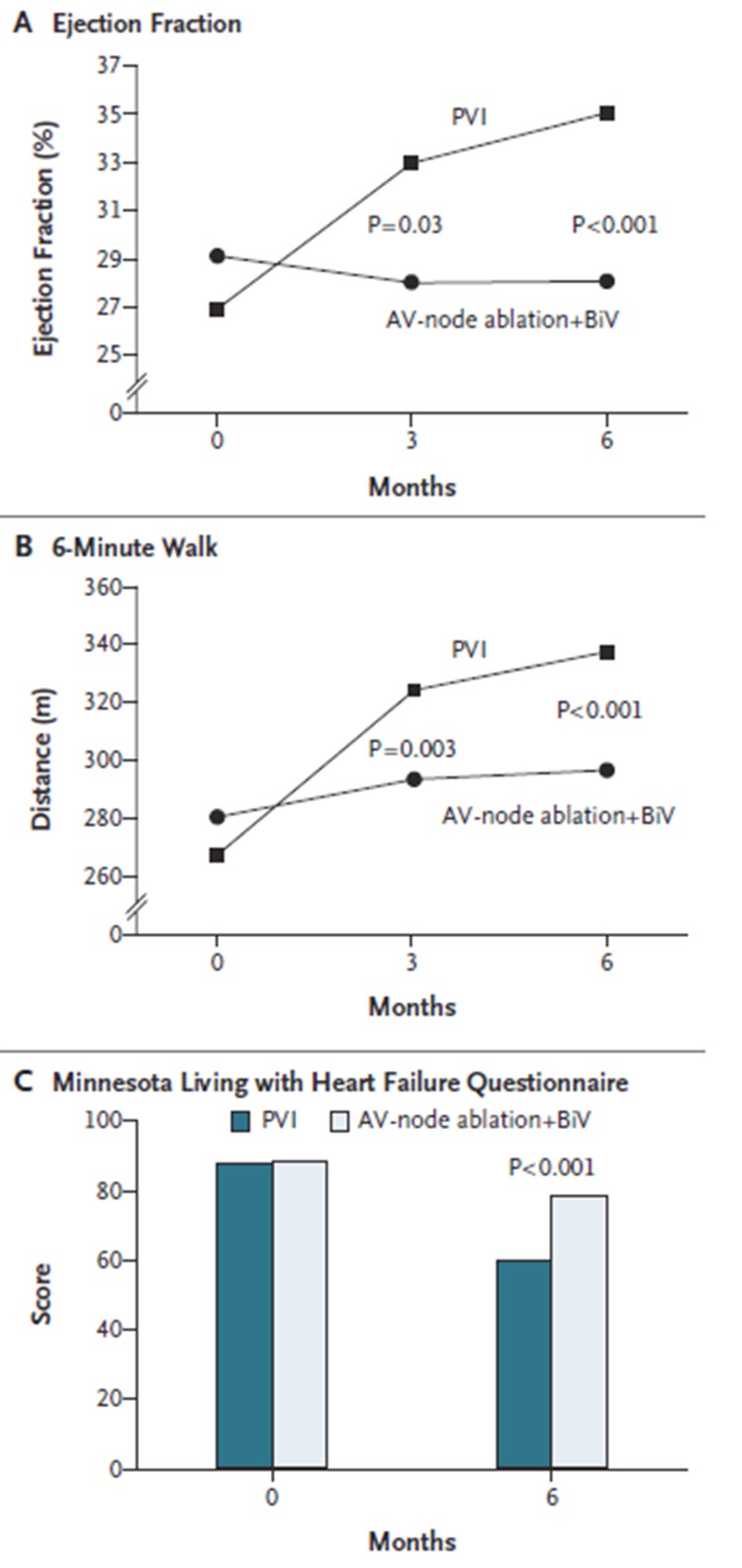

The PABA-CHF study was a prospective, multicenter clinical trial in which investigators randomly assigned 81 patients with symptomatic AF, LVEF <40% and NYHA Class II or III HF to either PVI or AVJ ablation.[37] At 6 months of follow-up, the composite end-point favored PVI. There was an improvement in Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire scores, 6 min hall walk test and EF ([Figure 5]). As an added benefit, nearly 70% of patients were free of AF off antiarrhythmic drugs at 6 months. Although a small study, the results suggest that PVI may offer another option in patients without making them pacemaker dependent.

Figure 5. Improvement in left ventricular (LV) function and dimensions after ablation in patients with congestive heart failure [Adapted from Khan et al. N Engl J Med 2004; 359: 1778-1785].

The results of these published series provide a potent rationale for a randomized clinical trial comparing the 3 modalities: ablation versus AVJ ablation versus pharmacologic therapy

Conclusions

CRT offers substantial symptomatic and mortality benefit in patients with severe HF. Evolving data suggest that patients with AF derive similar benefits as patients in sinus rhythm. However, response to CRT depends upon achieving complete BiV capture. In patients with AF and HF, it is imperative to assure that this is consistently and completely achieved to confer benefits to these patients. AVJ ablation and catheter ablation of AF offer promising approaches towards achieving this goal.

References

- 1.Steinberg Jonathan S. Desperately seeking a randomized clinical trial of resynchronization therapy for patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006 Aug 15;48 (4):744–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maisel William H, Stevenson Lynne Warner. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003 Mar 20;91 (6A):2D–8D. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calkins Hugh, Brugada Josep, Packer Douglas L, Cappato Riccardo, Chen Shih-Ann, Crijns Harry J G, Damiano Ralph J, Davies D Wyn, Haines David E, Haissaguerre Michel, Iesaka Yoshito, Jackman Warren, Jais Pierre, Kottkamp Hans, Kuck Karl Heinz, Lindsay Bruce D, Marchlinski Francis E, McCarthy Patrick M, Mont J Lluis, Morady Fred, Nademanee Koonlawee, Natale Andrea, Pappone Carlo, Prystowsky Eric, Raviele Antonio, Ruskin Jeremy N, Shemin Richard J. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for personnel, policy, procedures and follow-up. A report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed and approved by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2007 Jun;9 (6):335–79. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Thomas J, Larson Martin G, Levy Daniel, Vasan Ramachandran S, Leip Eric P, Wolf Philip A, D'Agostino Ralph B, Murabito Joanne M, Kannel William B, Benjamin Emelia J. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003 Jun 17;107 (23):2920–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cazeau S, Leclercq C, Lavergne T, Walker S, Varma C, Linde C, Garrigue S, Kappenberger L, Haywood G A, Santini M, Bailleul C, Daubert J C. Effects of multisite biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure and intraventricular conduction delay. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001 Mar 22;344 (12):873–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleland John G F, Daubert Jean-Claude, Erdmann Erland, Freemantle Nick, Gras Daniel, Kappenberger Lukas, Tavazzi Luigi. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005 Apr 14;352 (15):1539–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vardas Panos E, Auricchio Angelo, Blanc Jean-Jacques, Daubert Jean-Claude, Drexler Helmut, Ector Hugo, Gasparini Maurizio, Linde Cecilia, Morgado Francisco Bello, Oto Ali, Sutton Richard, Trusz-Gluza Maria. Guidelines for cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: The Task Force for Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur. Heart J. 2007 Sep;28 (18):2256–95. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bristow Michael R, Saxon Leslie A, Boehmer John, Krueger Steven, Kass David A, De Marco Teresa, Carson Peter, DiCarlo Lorenzo, DeMets David, White Bill G, DeVries Dale W, Feldman Arthur M. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004 May 20;350 (21):2140–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young James B, Abraham William T, Smith Andrew L, Leon Angel R, Lieberman Randy, Wilkoff Bruce, Canby Robert C, Schroeder John S, Liem L Bing, Hall Shelley, Wheelan Kevin. Combined cardiac resynchronization and implantable cardioversion defibrillation in advanced chronic heart failure: the MIRACLE ICD Trial. JAMA. 2003 May 28;289 (20):2685–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leon Angel R, Greenberg Jeffrey M, Kanuru Narendra, Baker Cindy M, Mera Fernando V, Smith Andrew L, Langberg Jonathan J, DeLurgio David B. Cardiac resynchronization in patients with congestive heart failure and chronic atrial fibrillation: effect of upgrading to biventricular pacing after chronic right ventricular pacing. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002 Apr 17;39 (8):1258–63. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01779-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molhoek Sander G, Bax Jeroen J, Bleeker Gabe B, Boersma Eric, van Erven L, Steendijk Paul, van der Wall Ernst E, Schalij Martin J. Comparison of response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with sinus rhythm versus chronic atrial fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004 Dec 15;94 (12):1506–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linde Cecilia, Leclercq Christophe, Rex Steve, Garrigue Stephane, Lavergne Thomas, Cazeau Serge, McKenna William, Fitzgerald Melissa, Deharo Jean-Claude, Alonso Christine, Walker Stuart, Braunschweig Frieder, Bailleul Christophe, Daubert Jean-Claude. Long-term benefits of biventricular pacing in congestive heart failure: results from the MUltisite STimulation in cardiomyopathy (MUSTIC) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002 Jul 03;40 (1):111–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khadjooi K, Foley P W, Chalil S, Anthony J, Smith R E A, Frenneaux M P, Leyva F. Long-term effects of cardiac resynchronisation therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2008 Jul;94 (7):879–83. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.129429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upadhyay Gaurav A, Choudhry Niteesh K, Auricchio Angelo, Ruskin Jeremy, Singh Jagmeet P. Cardiac resynchronization in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008 Oct 07;52 (15):1239–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gasparini Maurizio, Regoli François, Galimberti Paola, Ceriotti Carlo, Cappelleri Alessio. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2009 Nov;11 Suppl 5 ():v82–6. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koneru Jayanthi N, Steinberg Jonathan S. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in the setting of permanent atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2008 Jan;23 (1):9–15. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3282f303ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melenovsky Vojtech, Hay Ilan, Fetics Barry J, Borlaug Barry A, Kramer Andrew, Pastore Joseph M, Berger Ronald, Kass David A. Functional impact of rate irregularity in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur. Heart J. 2005 Apr;26 (7):705–11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Late-Breaking Basic Science Abstracts. From the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2007 Orlando, Florida November 4 - 7, 2007. Circ. Res. 2007 Nov 02; () [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swerdlow Charles D, Friedman Paul A. Advanced ICD troubleshooting: Part II. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006 Jan;29 (1):70–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamath Ganesh S, Cotiga Delia, Koneru Jayanthi N, Arshad Aysha, Pierce Walter, Aziz Emad F, Mandava Anisha, Mittal Suneet, Steinberg Jonathan S. The utility of 12-lead Holter monitoring in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation for the identification of nonresponders after cardiac resynchronization therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009 Mar 24;53 (12):1050–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricci Renato Pietro, Morichelli Loredana, Santini Massimo. Remote control of implanted devices through Home Monitoring technology improves detection and clinical management of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2009 Jan;11 (1):54–61. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brignole M, Gammage M, Puggioni E, Alboni P, Raviele A, Sutton R, Vardas P, Bongiorni M G, Bergfeldt L, Menozzi C, Musso G. Comparative assessment of right, left, and biventricular pacing in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2005 Apr;26 (7):712–22. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doshi Rahul N, Daoud Emile G, Fellows Christopher, Turk Kyong, Duran Aurelio, Hamdan Mohamed H, Pires Luis A. Left ventricular-based cardiac stimulation post AV nodal ablation evaluation (the PAVE study). J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2005 Nov;16 (11):1160–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.50062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasparini Maurizio, Auricchio Angelo, Metra Marco, Regoli François, Fantoni Cecilia, Lamp Barbara, Curnis Antonio, Vogt Juergen, Klersy Catherine. Long-term survival in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy: the importance of performing atrio-ventricular junction ablation in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2008 Jul;29 (13):1644–52. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira António M, Adragão Pedro, Cavaco Diogo M, Candeias Rui, Morgado Francisco B, Santos Katya R, Santos Emília, Silva José A. Benefit of cardiac resynchronization therapy in atrial fibrillation patients vs. patients in sinus rhythm: the role of atrioventricular junction ablation. Europace. 2008 Jul;10 (7):809–15. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Indik Julia H. Spontaneous conversion of atrial fibrillation in the setting of biventricular pacing. Cardiol Rev. 2003 Dec 12;12 (1):1–2. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000099620.26844.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gasparini Maurizio, Steinberg Jonathan S, Arshad Aysha, Regoli François, Galimberti Paola, Rosier Arnaud, Daubert Jean Claude, Klersy Catherine, Kamath Ganesh, Leclercq Christophe. Resumption of sinus rhythm in patients with heart failure and permanent atrial fibrillation undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy: a longitudinal observational study. Eur. Heart J. 2010 Apr;31 (8):976–83. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azpitarte J, Baún O, Moreno E, García-Orta R, Sánchez-Ramos J, Tercedor L. In patients with chronic atrial fibrillation and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, restoration of sinus rhythm confers substantial benefit. Chest. 2001 Jul;120 (1):132–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WG Butter C , M Schlegl . et al. Management of atrial fibrillation in cardiac resynchronization therapy Clinical practice of CRT: how to improve the success rate. Eur Heart J. 2004;0:0–0. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corley Scott D, Epstein Andrew E, DiMarco John P, Domanski Michael J, Geller Nancy, Greene H Leon, Josephson Richard A, Kellen Joyce C, Klein Richard C, Krahn Andrew D, Mickel Mary, Mitchell L Brent, Nelson Joy Dalquist, Rosenberg Yves, Schron Eleanor, Shemanski Lynn, Waldo Albert L, Wyse D George. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study. Circulation. 2004 Mar 30;109 (12):1509–13. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121736.16643.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy Denis, Talajic Mario, Nattel Stanley, Wyse D George, Dorian Paul, Lee Kerry L, Bourassa Martial G, Arnold J Malcolm O, Buxton Alfred E, Camm A John, Connolly Stuart J, Dubuc Marc, Ducharme Anique, Guerra Peter G, Hohnloser Stefan H, Lambert Jean, Le Heuzey Jean-Yves, O'Hara Gilles, Pedersen Ole Dyg, Rouleau Jean-Lucien, Singh Bramah N, Stevenson Lynne Warner, Stevenson William G, Thibault Bernard, Waldo Albert L. Rhythm control versus rate control for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008 Jun 19;358 (25):2667–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Earley M J, Abrams D J R, Staniforth A D, Sporton S C, Schilling R J. Catheter ablation of permanent atrial fibrillation: medium term results. Heart. 2006 Feb;92 (2):233–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.066969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Michael S, Marrouche Nassir F, Khaykin Yaariv, Gillinov A Marc, Wazni Oussama, Martin David O, Rossillo Antonio, Verma Atul, Cummings Jennifer, Erciyes Demet, Saad Eduardo, Bhargava Mandeep, Bash Dianna, Schweikert Robert, Burkhardt David, Williams-Andrews Michelle, Perez-Lugones Alejandro, Abdul-Karim Ahmad, Saliba Walid, Natale Andrea. Pulmonary vein isolation for the treatment of atrial fibrillation in patients with impaired systolic function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004 Mar 17;43 (6):1004–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu Li-Fern, Jaïs Pierre, Sanders Prashanthan, Garrigue Stéphane, Hocini Mélèze, Sacher Fréderic, Takahashi Yoshihide, Rotter Martin, Pasquié Jean-Luc, Scavée Christophe, Bordachar Pierre, Clémenty Jacques, Haïssaguerre Michel. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004 Dec 02;351 (23):2373–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tondo Claudio, Mantica Massimo, Russo Giovanni, Avella Andrea, De Luca Lucia, Pappalardo Augusto, Fagundes Rafael Lopes, Picchio Edo, Laurenzi Francesco, Piazza Vito, Bisceglia Irma. Pulmonary vein vestibule ablation for the control of atrial fibrillation in patients with impaired left ventricular function. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006 Sep;29 (9):962–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi Andrew D, Hematpour Khashayar, Kukin Marrick, Mittal Suneet, Steinberg Jonathan S. Ablation vs medical therapy in the setting of symptomatic atrial fibrillation and left ventricular dysfunction. Congest Heart Fail. 2010 Jan 19;16 (1):10–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2009.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan Mohammed N, Jaïs Pierre, Cummings Jennifer, Di Biase Luigi, Sanders Prashanthan, Martin David O, Kautzner Josef, Hao Steven, Themistoclakis Sakis, Fanelli Raffaele, Potenza Domenico, Massaro Raimondo, Wazni Oussama, Schweikert Robert, Saliba Walid, Wang Paul, Al-Ahmad Amin, Beheiry Salwa, Santarelli Pietro, Starling Randall C, Dello Russo Antonio, Pelargonio Gemma, Brachmann Johannes, Schibgilla Volker, Bonso Aldo, Casella Michela, Raviele Antonio, Haïssaguerre Michel, Natale Andrea. Pulmonary-vein isolation for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008 Oct 23;359 (17):1778–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]