Abstract

Incessant atrial premature beats as a potential cause for tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy was suspected in a patient presenting with dilated non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and severely altered left ventricular ejection fraction. The elimination of a left atrial focus by percutaneous RF ablation led to normalization of the clinical status, of atrial and ventricular dimensions and left ventricular systolic function.

Introduction

A 40 years old man was referred to our institution for the recent occurrence of congestive heart failure. He presented with dyspnea (NYHA class II) together with palpitations since a few months, culminating with a recent episode of acute pulmonary oedema. The patient had no significant personal or familial medical history and was previously not under any medical treatment. The echocardiography revealed dilated left atrium (32 cm2) and left ventricle (end-diastolic volume 300 cc, end-diastolic diameter 71 mm) with altered left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF 28%) without hypertrophy (12 mm septum and 10 mm posterior wall thickness) and without any specific etiology after complete investigations including MRI and coronary angiography.

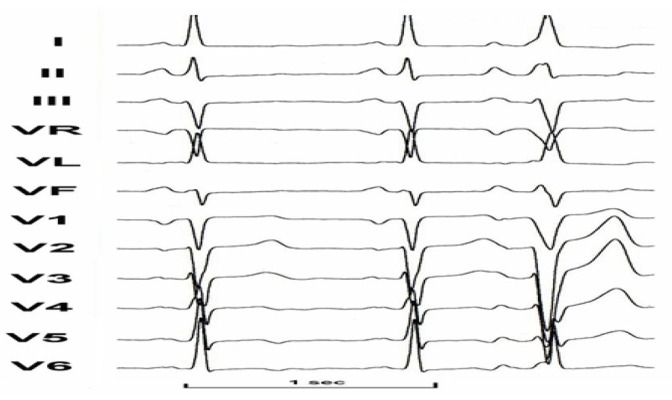

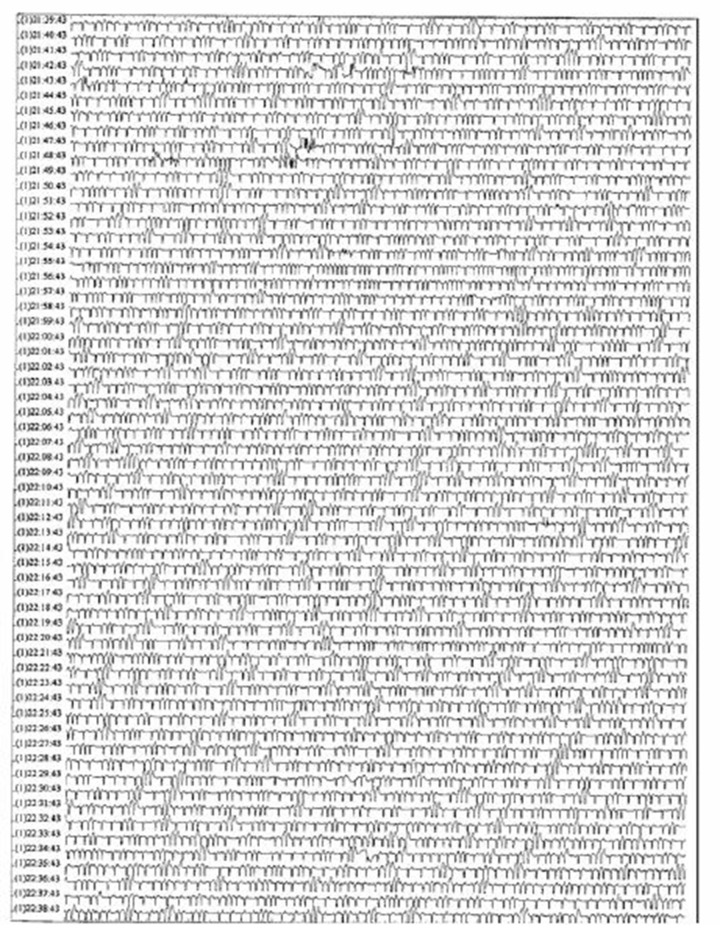

Baseline ECG revealed incessant isolated or short salvos of monomorphic atrial premature beats, with or without aberrant intraventricular conduction. P wave morphology of the premature beats was indicative of a right superior pulmonary vein origin (fig 1).[1] Aberrant conduction was essentially of the left bundle branch block pattern. Both 24 hours ambulatory recordings realized before admission found around 35000 to 40000 premature beats (around 35-40 % of the daily cardiac beats). Around 15000 daily atrial premature beats (15% of the cardiac beats) were still present at our institution while on beta-blockers and amiodarone, with a large part of them (around 10000) being conducted to the ventricles with various degrees of aberrancy. Atrial premature beats were isolated (around 3500) or groups in doublets (around 4500 doublets) or short salvos (around 400 salvos, the longer lasted 5 seconds at 151 bpm) (fig 2). Most of the time, bigeminy or trigeminy was present, and there was no evidence of interpolated beats or of non-conducted premature beats. Mean ventricular heart rate was 70-73 bpm.

Figure 1. 12-Lead ECG Showing the Atrial Premature Beat with P/T Phenomenon, with Positive P Wave in the Inferior Leads (Amplitude in Lead II > Lead III), +/- in Lead V1 and Negative P Wave in VL Evocative of a Right Pulmonary Vein Origin.

Figure 2. One Lead Tracing from Initial Ambulatory Recording (One Hour Duration) Showing the Incessant Nature of Premature Atrial Beats, With or Without Aberrancy, Mostly Grouped in Doublets-Triplets.

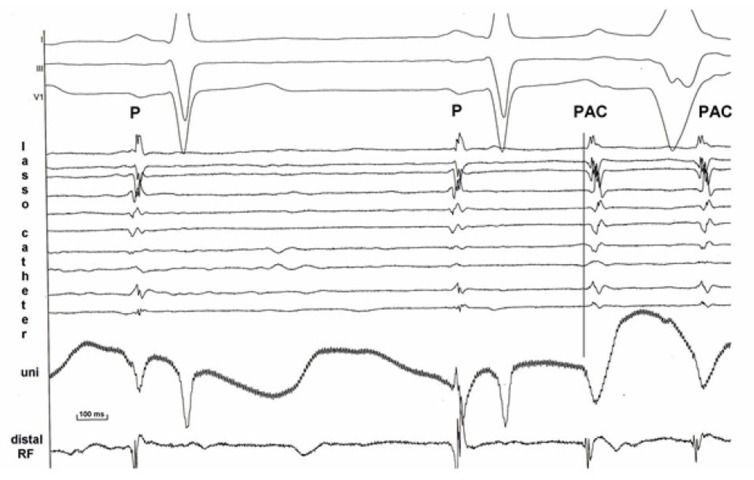

A tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy related to the numerous atrial premature beats was suspected, although a primitive dilated cardiomyopathy complicated by atrial arrhythmias was initially not excluded. For discriminating between both hypothesis, we decided to perform a percutaneous radio-frequency (RF) ablation. Because of the P wave morphologies indicative of an origin from the superior pulmonary veins, both superior left and right veins were disconnected using segmental ostial RF ablation with a circular multipolar catheter under fluoroscopy. Both veins were highly electrically connected with extended pulmonary veins potentials, most of the atrial premature beats during this procedure coming from the right superior one (fig 3). Only exceptional premature beats were still observed after complete disconnection of both veins. Hence, both inferior pulmonary veins and the superior vena cava were not checked. Post-procedural ambulatory recording however still found around 13000 atrial premature beats (12 % of the cardiac beats) (5000 isolated, 3000 doublets, 650 short salvos). Post-procedural LVEF was found unchanged (23 % at MRI). The patient was discharged under beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE).

Figure 3. Intracardiac Recording Showing the Premature Atrial Beat Arising from the Right Superior Pulmonary Vein : Earliest Activation was Recorded on the Multipolar Lasso Catheter or Distal RF Catheter (*) Positioned at the Right Superior Pulmonary Vein 20 msec before Ectopic P Wave onset, while Recorded 60 msec after P Wave onset and Preceded By Far-Field Atrial potentials (Arrow) During Sinus Rhythm. P= Sinus Node P Wave. PAC= Premature Atrial Contraction.

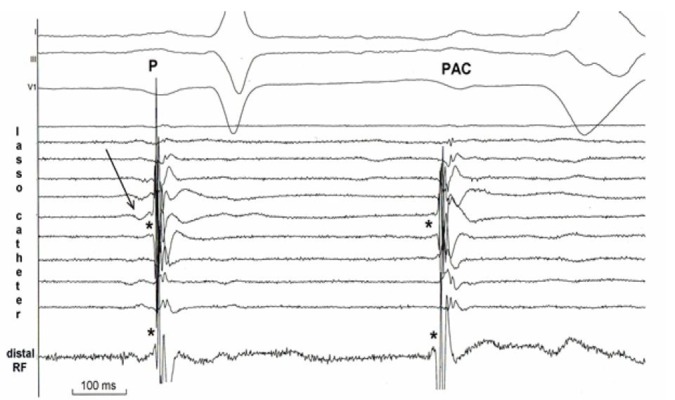

Two months later, the patient worsened (NYHA class III, LVEF 30 %) and there were still around 25 000 atrial premature beats on 24 hours recording despite beta-blockers (25% of the total cardiac beats). Ectopic P waves morphology was unchanged, again indicative of a right superior pulmonary vein origin. Therefore, a new RF ablation was attempted using the same technique. Both superior veins were found reconnected, and a total of five pulmonary veins (two left and three right pulmonary veins) could be completely disconnected. At the beginning of this second procedure, the ectopic beats were shown to mainly arise from the three right veins. However, atrial premature beats with a similar unchanged morphology were still present after complete pulmonary vein disconnection, indicating the existence of an additional non-venous focus. Superior vena cava was not electrically connected to the right atrium. A mapping of the left atrium was performed using fluoroscopy, allowing to locate the ectopic focus on the upper septal part of the left atrial posterior wall, at mid-distance between the antrum of the superior and inferior veins (fig 4). Three minutes RF application at this site definitively eliminated all atrial ectopies. There were only 86 atrial premature beats during the following 24 hours and the patient was discharged under warfarin, beta-blockers, ACE and diuretic.

Figure 4. Intracardiac Recording at the Site of Successful RF Ablation (Left Atrial Posterior Wall, See Text). The Multipolar Lasso Catheter was Positioned on the Posterior Wall Near the Right Pulmonary Veins Antrum. At that Site, During Premature Atrial Beats, a Clear QS Pattern was Ppresent on Unipolar Recording from the Distal Tip of the RF Catheter (« uni ») as well as Earliest Deflection on the Bipolar Distal Dipole of the RF Catheter (« distal RF ») (20 msec Earlier than P Wave onset on ECG). Same Abbreviations as in Figure 3.

Five months later, the patient was completely asymptomatic, and there was only 29 daily atrial premature beats. LVEF was improved (45 %) with almost normal left ventricle dimensions (end-diastolic diameter 58 mm). Finally, two months later, under the same medications except diuretic, the patient is doing very well, with permanent regular sinus rhythm. The LVEF is almost normalized (50%) as were left atrial (12 cm²) and ventricular dimensions (end-diastolic diameter 58 mm or 26 mm/m², end-diastolic volume 120 cc or 56 cc/m²). Surprisingly, a left ventricular hypertrophy (15 mm septal thickness) was present which had not been noted before. This left ventricular hypertrophy was found again two years after the procedure (14 mm septum and 15 mm posterior wall thickness) while the patient was considered cured from arrhythmias and heart failure (LVEF 60%).

Discussion

Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy has been described for 25 years .[2–4] The reversal of left ventricular systolic dysfunction is usually observed after elimination of the tachycardia by ablation or drugs. Various arrhythmias may be involved, such as persistent or incessant various kinds of atrial tachycardia, permanent forms of junctional reciprocating tachycardia or incessant ventricular tachycardia. Frequent isolated premature ventricular contractions have been more recently recognized as a potential cause of “arrhythmia-induced” cardiomyopathy.[5–8] whose mechanism is debated.[4]

Despite a lot of publications in this area, no case of “arrhythmia-induced” myocardiopathy related to frequent premature atrial contractions does seem to have been described. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of “atrial premature beats-related” cardiomyopathy. Even though this case may be linked to the more usual tachyFigure cardia-induced cardiomyopathy associated with atrial fibrillation,[9] it is interesting to observe that numerous ectopic atrial premature beats, essentially isolated or grouped in doublets, may create so severe but reversible left ventricle dysfunction. Deleterious consequences of isolated atrial beats are probably very uncommon due to the lack of previously described similar cases.

This case demonstrates again the reversal of arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathies. Indeed the LVEF improves only after the successful ablation, with decreased diameters and volumes due to reverse remodeling of the left ventricle and left atrium. The diagnosis of arrhythmia-induced myocardiopathy remains however only retrospective after the improvement of the LVEF following elimination of the arrhythmia. This is the reason why aggressive care is necessary in each case when a diagnostic of arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy is evoked.

It is difficult to evaluate the minimal number of daily premature beats over which an arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy is likely. Several studies conclude that the risk for arrhyhmia-induced cardiomyopathy was present when premature ventricular beats are over 1000010 to 2000011 premature beats per 24 hours or over 24 % of the cardiac beats,[8] but cases were reported with far less i.e. 7800 5 or even 5500 daily.[12] 15000 to 40000 daily premature beats were present in our patient according to the different steps of his medical history (15 to 40% of the cardiac beats), therefore the minimal number of atrial premature beats inducing cardiomyopathy is probably less, even if still unknown. The minimal number of atrial premature beats required for suspecting an arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy may however not be similar to the minimal number of ventricular premature beats in this situation.

There are a lot of hypothesis about the physio-pathological mechanisms involved in arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy. Cellular mechanisms probably associated myocardial energy depletion, alterations in cellular calcium metabolism, oxida tive stress, ischemia/anoxia or apoptosis .[2–4] Hemodynamic consequences of the culprit arrhythmia may also be involved, including the accelerated heart rate, the reduced left ventricular filling due to the reduced diastolic time, intra or interventricular dyssynchrony induced by ventricular beats or intraventricular conduction disturbances, or the hemodynamic deleterious consequences of an irregular cardiac rate.[2–4] Paradoxically however, some tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathies are not associated with a fast heart rate, for example in some cases of atrial fibrillation with slowed ventricular rate, evoking here the role of the loss of atrial contraction.[9] In the same way, the mean ventricular heart rate was not increased in our patient despite the numerous premature beats, owing to their rather long coupling interval (P/T phenomenon). Finally, individual sensitivity, maybe due to still unknown genetic background, is commonly seen in clinical practice, since only a minority of patients with numerous atrial or ventricular premature beats did present with progressive ventricular remodeling.

Finally, despite LVEF normalization, it is important to know if there was a further underlying structural heart disease in this patient since a persistent left ventricular hypertrophy was noted during the follow-up, which was not initially observed. This could be the marker of an evolutive underlying structural heart disease, but this may also be a consequence of the ventricular remodeling. Indeed few experimental studies with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathies models had shown a left ventricular hypertrophy associated with the left ventricular remodeling after normalization of rhythm disorders. This hypertrophy was associated to histological modifications, in particular to an extracellular increase in collagen .[12,13]

Disclosures

No disclosures relevent to this article were made by the authors.

References

- 1.Yamane T, Shah D C, Peng J T, Jaïs P, Hocini M, Deisenhofer I, Choi K J, Macle L, Clémenty J, Haïssaguerre M. Morphological characteristics of P waves during selective pulmonary vein pacing. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001 Nov 01;38 (5):1505–10. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaran C J, Gersh B J, Sugrue D D, Hammill S C, Seward J B, Holmes D R. Tachycardia induced myocardial dysfunction. A reversible phenomenon? Br Heart J. 1985 Mar;53 (3):323–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.53.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packer D L, Bardy G H, Worley S J, Smith M S, Cobb F R, Coleman R E, Gallagher J J, German L D. Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy: a reversible form of left ventricular dysfunction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1986 Mar 01;57 (8):563–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simantirakis Emmanuel N, Koutalas Emmanuel P, Vardas Panos E. Arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathies: the riddle of the chicken and the egg still unanswered? Europace. 2012 Apr;14 (4):466–73. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taieb Jerome M, Maury Philippe, Shah Dipen, Duparc Alexandre, Galinier Michel, Delay Marc, Morice Ronan, Alfares Ali, Barnay Claude. Reversal of dilated cardiomyopathy by the elimination of frequent left or right premature ventricular contractions. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2007 Nov;20 (1-2):9–13. doi: 10.1007/s10840-007-9157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimm W, Menz V, Hoffmann J, Maisch B. Reversal of tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy following ablation of repetitive monomorphic right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001 Feb;24 (2):166–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogun Frank, Crawford Thomas, Reich Stephen, Koelling Todd M, Armstrong William, Good Eric, Jongnarangsin Krit, Marine Joseph E, Chugh Aman, Pelosi Frank, Oral Hakan, Morady Fred. Radiofrequency ablation of frequent, idiopathic premature ventricular complexes: comparison with a control group without intervention. Heart Rhythm. 2007 Jul;4 (7):863–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baman Timir S, Lange Dave C, Ilg Karl J, Gupta Sanjaya K, Liu Tzu-Yu, Alguire Craig, Armstrong William, Good Eric, Chugh Aman, Jongnarangsin Krit, Pelosi Frank, Crawford Thomas, Ebinger Matthew, Oral Hakan, Morady Fred, Bogun Frank. Relationship between burden of premature ventricular complexes and left ventricular function. Heart Rhythm. 2010 Jul;7 (7):865–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu Li-Fern, Jaïs Pierre, Sanders Prashanthan, Garrigue Stéphane, Hocini Mélèze, Sacher Fréderic, Takahashi Yoshihide, Rotter Martin, Pasquié Jean-Luc, Scavée Christophe, Bordachar Pierre, Clémenty Jacques, Haïssaguerre Michel. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004 Dec 02;351 (23):2373–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takemoto Masao, Yoshimura Hitoshi, Ohba Yurika, Matsumoto Yasuharu, Yamamoto Umpei, Mohri Masahiro, Yamamoto Hideo, Origuchi Hideki. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of premature ventricular complexes from right ventricular outflow tract improves left ventricular dilation and clinical status in patients without structural heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005 Apr 19;45 (8):1259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sekiguchi Yukio, Aonuma Kazutaka, Yamauchi Yasuteru, Obayashi Tohru, Niwa Akihiro, Hachiya Hitoshi, Takahashi Atsushi, Nitta Junichi, Iesaka Yoshito, Isobe Mitsuaki. Chronic hemodynamic effects after radiofrequency catheter ablation of frequent monomorphic ventricular premature beats. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2005 Oct;16 (10):1057–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.40786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarlagadda Ravi K, Iwai Sei, Stein Kenneth M, Markowitz Steven M, Shah Bindi K, Cheung Jim W, Tan Vivian, Lerman Bruce B, Mittal Suneet. Reversal of cardiomyopathy in patients with repetitive monomorphic ventricular ectopy originating from the right ventricular outflow tract. Circulation. 2005 Aug 23;112 (8):1092–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.546432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomita M, Spinale F G, Crawford F A, Zile M R. Changes in left ventricular volume, mass, and function during the development and regression of supraventricular tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. Disparity between recovery of systolic versus diastolic function. Circulation. 1991 Feb;83 (2):635–44. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spinale F G, Tomita M, Zellner J L, Cook J C, Crawford F A, Zile M R. Collagen remodeling and changes in LV function during development and recovery from supraventricular tachycardia. Am. J. Physiol. 1991 Aug;261 (2 Pt 2):H308–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.2.H308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]