Abstract

Identifying quantitative trait locus (QTL) genes is a challenging task. Herein, we report using a two-step process to identify Apoa2 as the gene underlying Hdlq5, a QTL for plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) levels on mouse chromosome 1. First, we performed a sequence analysis of the Apoa2 coding region in 46 genetically diverse mouse strains and found five different APOA2 protein variants, which we named APOA2a to APOA2e. Second, we conducted a haplotype analysis of the strains in 21 crosses that have so far detected HDL QTLs; we found that Hdlq5 was detected only in the nine crosses where one parent had the APOA2b protein variant characterized by an Ala61-to-Val61 substitution. We then found that strains with the APOA2b variant had significantly higher (P ≤ 0.002) plasma HDL levels than those with either the APOA2a or the APOA2c variant. These findings support Apoa2 as the underlying Hdlq5 gene and suggest the Apoa2 polymorphisms responsible for the Hdlq5 phenotype. Therefore, haplotype analysis in multiple crosses can be used to support a candidate QTL gene.

Most common human diseases, such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, and obesity, are complex traits determined by many genetic and environmental factors. The genetic factors are usually studied in animal models, most commonly mice, and frequently through a process known as quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis, which has the advantage of finding novel key genes in a metabolic pathway. To date, more than 1800 mouse QTLs have been found (Mouse Genome Informatics, http://www.informatics.jax.org); however, identifying the genes underlying these QTLs has been an extremely challenging task (Nadeau and Frankel 2000; Korstanje and Paigen 2002).

The level of plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), although not a disease, is also a complex trait. It has been intensely studied because, in humans, it is inversely correlated with the risks of coronary artery disease, and therapies that raise HDL levels may significantly reduce these risks (Boden and Pearson 2000). QTL analysis has identified many genomic regions that regulate HDL levels, both in mice and in humans—to date, 37 mouse and 29 human HDL QTLs have been identified (update of review by Wang and Paigen 2002). One of the mouse HDL QTLs, Hdlq5 (Wang et al. 2003), on distal chromosome 1 (cM 92), has been repeatedly identified in nine of those crosses (update of review by Wang and Paigen 2002). An obvious candidate for the Hdlq5 gene was Apoa2 (cM 92.6), because its encoded protein, apolipoprotein A-II (APOA2), helps maintain plasma HDL levels in mice (for review, see Blanco-Vaca et al. 2001).

To determine whether Apoa2 was the Hdlq5 gene, we took the approach of haplotype analysis. Recent single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) maps indicate that the genome of common inbred mouse strains is defined by 1-2 Mb haplotype blocks (Wade et al. 2002; Wiltshire et al. 2003), which can be used to narrow a QTL, because its underlying gene should be in subregions where the parental strains have different haplotypes (Park et al. 2003; Manenti et al. 2004). We extended this haplotype analysis further by using it to identify a QTL gene. In doing so, we performed a sequence analysis of the coding region of Apoa2 in 46 genetically diverse mouse strains, and a haplotype analysis of strains both in the nine crosses that detected Hdlq5 and in the 12 crosses that failed to detect Hdlq5. We found that not only did the haplotype analysis support Apoa2 as the Hdlq5 gene, but it also suggested that the Apoa2 mutation is responsible for the Hdlq5 phenotype. Thus, haplotype analysis in multiple crosses can be used to support a QTL gene.

RESULTS

Inbred Mouse Strains Have Five APOA2 Protein Types

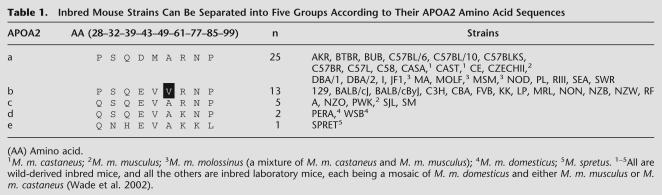

Polymorphisms of mouse Apoa2 coding sequence have been reported before; a total of 15 SNPs cause eight amino acid changes in APOA2 (Doolittle et al. 1990; Higuchi et al. 1991; Purcell-Huynh et al. 1995; Suto et al. 1999; Kitagawa et al. 2003). For our purpose of testing Apoa2 as the candidate gene for Hdlq5, we sequenced all four Apoa2 exons in 46 genetically diverse and widely used inbred mouse strains, including 43 whose plasma HDL concentrations were known (Mouse Phenome Database, http://www.jax.org/phenome) and three that were parents in crosses to map HDL QTLs (CASA, MRL, and NZO). We found that the four exons of Apoa2 had a total of 16 SNPs, resulting in nine amino acid changes and producing five APOA2 protein variants, which we named type “a” (APOA2a) to “e” (APOA2e; see Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1). The “b” strains were distinct with regard to two features: Their APOA2 sequence had an Ala61-to-Val61 substitution, and none of them were wild-derived strains (all were inbred laboratory mice). The other APOA2 types each had at least one wild-derived strain: “a” type contains M. m. castaneus, M. m. musculus, and M. m. molossinus (a mixture of the previous two); “c” type contains M. m. musculus; “d” type contains M. m. domesticus; and “e” type contains M. spretus.

Table 1.

Ala61 Is Conserved in Eight Mammalian Species

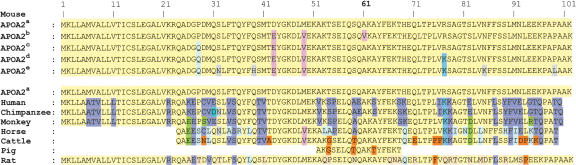

By comparing the APOA2 peptide sequences of eight mammal species, we found that APOA2 Ala61 was conserved in mice (except those having APOA2b), humans, chimpanzees, monkeys, horses, cattle, pigs, and rats (Fig. 1), suggesting that Val61 is a mutation in mice with APOA2b.

Figure 1.

APOA2 protein sequence comparison in eight mammal species. Amino acids that are identical to those in mice having APOA2a, APOA2b, APOA2c, APOA2d, and APOA2e are highlighted yellow, rose, light green, pale blue, and gray, respectively; those that are identical to APOA2 from human (lavender), chimpanzee (sky blue), monkey (green), horse (light turquoise), cattle (orange), and rat (tan) are also highlighted. Sources, with GenBank accession no. or reference: Human (Homo sapiens), NP_037244; Chimpanzee (Pan troglodyte), AAM49808; Cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis), P18656; Horse (Equus caballus), D. Puppione (pers. comm.); Cattle (Bos taurus), P81644; Pig (Sus scrofa), CAD91908; Rat (Rattus norvegicus), NP_037244.

Hdlq5 Was Only Detected in Crosses Whose Parental Strains Differed at APOA2 Amino Acid 61

Of the 21 different mouse crosses used to identify HDL QTLs, Hdlq5 was found only in the nine where one parent carried APOA2b and the second parent carried other APOA2 types (Table 2). Because mice with APOA2b have a unique Val61, our results clearly showed that Hdlq5 was found only when the two parental strains differed at amino acid 61, that is, one should carry Ala61 and the other should carry Val61. Hdlq5 may not be detected even though the two parental strains have different APOA2 types; for example, Hdlq5 was not found when C57BL/6 (having APOA2a) and SPRET (having APOA2e) were crossed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hdlq5 Was Only Detected When the Two Parental Strains in a Cross Differed at AA61 of APOA2

| Cross

|

APOA2 AA

|

Ala61 × Val61

|

Ala61 × Ala61

|

Val61 × Val61

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOA2 type | a × b | b × c | a × a | a × e | c × c | b × b | |

| Hdlq5 detected | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | |

| Examples | B6 × 129,1 B6 × C3H,2 B6 × FVB,3 B6 × KK,4 B6 × NZB,5 CAST × 129,6 RIIIS × 1297 | NZB × SM,8 SJL × 1299 | AKR × DBA/2,10 B6 × CASA,11 B6 × CAST,12 B6 × DBA,13 CAST × DBA,14 MOLF × B615 | B6 × SPRET16 | SJL × NZO,17 SM × A18 | BALB × KK,19KK × RR,20MRL/pr × BALB21 | |

(AA) Amino acid. The strains with the “b” allele (Val61) are underlined. 1Ishimori et al. 2004; 2Machleder et al. 1997; Mehrabian et al. 1993; 3Dansky et al. 1999; 4Suto et al. 1999; 5Wang et al. 2003; 6Lyons et al. 2004b; 7Lyons et al. 2004a; Korstanje et al. 2004; Mehrabian et al. 1993; Purcell-Huynh et al. 1995; 9Schwarz et al. 2001; 10Schwarz et al.; 11Sehayek et al. 2003; 12Mehrabian et al. 2000; 13Colinayo et al. 2003; 14Lyons et al. 2003; 15Welch et al. 2001; 16Warden et al. 1993; 17Giesen et al. 2003; 18Anunciado et al. 2000; 19Shike et al. 2001; 20Suto and Sekikawa 2003; 21Gu et al. 1999.

Haplotype analysis of the strains carrying APOA2b excluded the possibility that an unknown gene in linkage disequilibrium with Apoa2 was underlying Hdlq5 in these nine crosses: The APOA2b strains do not share a common haplotype block near Apoa2 (Table 3). The nearby SNPs reduced the region the strains shared to one containing only two genes, Apoa2 and Fcer1g (Fc receptor, IgE, high affinity I, γ polypeptide). There is no evidence that Fcer1g is involved in lipoprotein metabolism.

Table 3.

Haplotype Analysis of Apoa2 Region in Mice with APOA2b

|

|

|

|

|

Strains with APOA2b

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker1 | Gene2 | Start (bp)3 | End (bp)3 | 129 | BALB | C3H | CBA | FVB | KK | LP | NON | NZB | NZW | RF |

| Wrn3 | 175048841 | 175048962 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Nr1i3 | 175071723 | 175076568 | ||||||||||||

| Wrn1 | 175081943 | 175082139 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Apoa2 | 175082812 | 175084093 | ||||||||||||

| Fcer1g | 175087300 | 175092009 | ||||||||||||

| Wrs1 | 175092624 | 175092806 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ndufs2 | 175092583 | 175104835 | ||||||||||||

| Wrs31 | 175106847 | 175107095 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

Microsatellite markers that we designed. We used PCR to amplify them. PCR products were scored according their sizes, with 1 < 2 < 3 in size. The sequences of the PCR primers for these markers are: Wrn3: forward: 5′-CCCAAAGGATTTACACATGC-3′, reverse: 5′-TACATACACCTGCCACATGC-3′; Wrn1: forward: 5′-TGCAGCATTTTCTCTGTGTG-3′, reverse: 5′-AAGGAATGGGGGTTATGAAG-3′; Wrs1: forward: 5′-CTAGTTCATGCACAGAAAGCC-3′, reverse: 5′-CCAGGATATTGTGTTCGGAG-3′; Wrs3: forward: 5′-AGTTCCCTCCTCTAACACCC-3′, reverse: 5′-CACCCAGAAGTCATCTCTGC-3′.

Genes that are closest to Apoa2, according to Ensembl Mouse Genome Server (http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/), Build 32.

Positions were retrieved from Ensembl Mouse Genome Server (http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus), Build 32. The distance from the neighboring genes to Apoa2: Nr1i3: 6244 bp; Fcer1g: 3207 bp; Nudfs2: 8490 bp.

Mice with APOA2b Had Higher Plasma HDL Concentrations Than Did Those With Either APOA2a or APOA2c

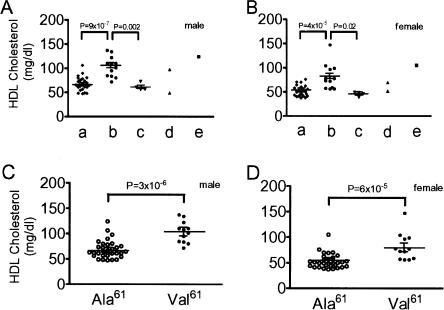

To determine whether any of the APOA2 variants were associated with variant plasma HDL levels, we analyzed the plasma HDL concentrations of the 43 inbred mouse strains from the Mouse Phenome Database. In male mice, HDL levels of strains having APOA2b (103 ± 6 mg/dL, mean ± SEM, 12 strains) were significantly higher than those of strains having either APOA2a (67 ± 3 mg/dL, n = 24) or APOA2c (62 ± 4 mg/dL, n = 4) (P = 9 × 10-7 and P = 0.002, respectively; Fig. 2A). Similar results were found in female mice: HDL levels of strains having APOA2b (81 ± 8 mg/dL, n = 12) were significantly higher than those of strains having either APOA2a (52 ± 2 mg/dL, n = 24) or APOA2c (46 ± 2 mg/dL, n = 4) (P = 4 × 10-5 and P = 0.02, respectively; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

HDL concentrations in inbred mouse strains with five types of APOA2. The 43 strains were separated into five types (24 “a,” 12 “b,” 4 “c,” 2 “d,” and 1 “e”) according to amino acids located at nine different APOA2 positions (see Table 1). Plasma HDL concentrations (mean ± SEM, mg/dL) were obtained from groups of 7- to 10-week-old males (A) and females (B) fasted for 4 h (all the strains in Table 1 except CASA, MRL, and NZO; Mouse Phenome Database). Each group consisted of between 10 and 40 mice (24 ± 7 males and 22 ± 6 females, mean ± SD). Plasma concentrations of HDL in male (C) and female (D) mice with Ala61 (all the strains except APOA2b mice) and those with Val61 (APOA2b mice) were also compared.

The distinguishing feature of the APOA2b is the presence of the amino acid substitution of alanine to valine at position 61. HDL levels of strains having Val61 were significantly higher than those having Ala61 in both male and female mice (103 ± 6 vs. 69 ± 3 mg/dL, P = 3 × 10-6, and 81 ± 8 vs. 53 ± 3 mg/dL, P = 6 × 10-5, respectively; Fig. 2C,D).

DISCUSSION

Identifying the gene underlying a QTL is a challenging task. Whereas considerable success has been achieved in identifying genes responsible for Mendelian traits—more than 1400 genes for them have been found (Page et al. 2003), fewer than 50 have been identified for polygenic or quantitative traits (Glazier et al. 2002; Korstanje and Paigen 2002).

Although there is no “gold standard” for positively identifying a QTL gene, the Complex Trait Consortium recently suggested that an identified gene should meet more than one of the following eight criteria (Biola et al. 2003): (1) polymorphisms in either its coding or regulatory regions have been found; its function has been (2) linked to the quantitative trait being analyzed, (3) tested in vitro, (4) tested in transgenic animals, (5) tested in knock-in animals, (6) assessed in deficiency-complementation tests, or (7) tested by mutational analysis; and (8) it has an homologous QTL for the same phenotype in another species. The most conclusive evidence comes from knock-in studies by replacing one allele with another and testing for function. We herein report using haplotype analysis in multiple crosses as a way of testing polymorphisms (criterion 1) to provide genetic evidence that a gene underlies a QTL.

By using this genetic approach, we provided two strong lines of evidence that Apoa2 underlies Hdlq5. First, haplotypes of Apoa2 were associated with plasma HDL concentrations: Mice with APOA2b had significantly higher plasma HDL levels than those with either APOA2a or APOA2c. Second, among the 21 crosses used to map HDL QTL, Hdlq5 was only detected in the nine where the parental strains had different amino acid at position 61 in APOA2 protein. We excluded the possibility that a gene in linkage disequilibrium with Apoa2 was underlying Hdlq5 because Fcer1g, the only gene that was in linkage disequilibrium with Apoa2, has no known functions in lipoprotein metabolism.

Haplotype analysis enabled us not only to identify Apoa2 as the gene for Hdlq5 but also to pinpoint the Ala61-to-Val61 substitution as the possible causal change for this QTL. First, mice with Val61 had significantly higher HDL levels than did those with Ala61. Second, Hdlq5 was only found in the crosses in which one parental strain had Val61 and the other had Ala61 in APOA2. Third, in the nine crosses that detected Hdlq5, the strain with Val61 always had the high allele of this QTL. This method may not be limited to finding a QTL gene with amino acid differences among the parental strains; it may also be used to find the key SNPs in the regulatory elements of a candidate gene.

Although Apoa2 is mostly likely the gene underlying Hdlq5, and Ala61-to-Val61 substitution in APOA2 is most probably the causal polymorphism, other possibilities exist. First, polymorphisms in the promoter region of Apoa2 may lead to mRNA difference and thereby difference in plasma HDL levels. The following results, however, suggest that there is no correlation between Apoa2 mRNA and plasma HDL levels and that Apoa2 promoter polymorphisms are unlikely to affect plasma HDL levels. In the B6xNZB cross in which Hdlq5 was found, B6 mice (having APOA2a) have higher levels of Apoa2 mRNA but lower levels of plasma HDL levels, compared with NZB mice (having APOA2b) (P < 0.05) (Wang et al. 2003). In the B6xC3H cross in which Hdlq5 was found, B6 mice had lower levels of both Apoa2 mRNA and HDL levels, compared with C3H mice (having APOA2b; P < 0.05; X. Wang and B. Paigen, unpubl.). On the other hand, B6 mice have similar levels of Apoa2 mRNA but lower levels of plasma HDL levels, compared with BALB/c mice (Doolittle et al. 1990). Second, a polymorphic enhancer in the same haplotype as Apoa2 coding sequence may regulate another gene, and this gene could regulate HDL levels. Although unlikely, we cannot exclude this possibility.

It has been reported that compared with C57BL/6 mice (having APOA2a), BALB/c mice (having APOA2b) have similar liver Apoa2 mRNA levels, but higher APOA2 protein synthesis rate in hepatocytes (Doolittle et al. 1990). This suggests that a change in messenger sequence, presumably the nucleotide change that causes Ala61-to-Val61 substitution, increases the efficiency of Apoa2 messenger translation, leading to more rapid production of APOA2 protein and therefore larger HDL particle and higher plasma HDL concentrations. We found no sequence changes in the 3′- or 5′-UTR regions between C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Our findings are important for future HDL research for two reasons. First, to avoid Hdlq5, whose strength may mask other HDL QTLs (and hence their discovery), future HDL QTL mapping efforts in mice should cross parental strains with the same amino acid 61 in APOA2. Second, a human QTL for plasma HDL levels was identified in the APOA2 region (Elbein and Hasstedt 2002). To determine whether APOA2 regulates human HDL concentrations, APOA2 SNPs should be analyzed in human populations.

Obviously, the analysis we conducted will be more powerful when the same QTL is detected in multiple crosses. Now that about 1500 QTLs, many of which were detected in multiple mouse crosses, have been mapped in the mouse genome (http://informatics.jax.org) and a wide variety of phenotypic data from many commonly used and genetically diverse mouse strains are easily accessible in the Mouse Phenome Database (hppt://www.jax.org/phenome), many QTL genes can be discovered quickly by analyzing their SNPs and haplotypes in multiple crosses, as exemplified in this study.

METHODS

Obtaining and Genotyping Genomic DNA

We obtained genomic DNA from Mouse DNA Resource at the Jackson Laboratory (http://www.jax.org/dnares/index.html). PCR genotyping of the four microsatellite markers (Wrn3, Wrn1, Wrs1, and Wrs3) in the Apoa2 region was carried out for 35 cycles under the following conditions: 94°C, 30 sec; 55°C, 30 sec; 72°C, 1 min. Polymorphisms were detected by electrophoresing the PCR products on 4% Nusieve 3:1 agarose gels in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA running buffer for 2 h at 190 volts. Gels were then stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under ultraviolet light.

Sequencing Apoa2

To define Apoa2 haplotypes, we sequenced the four exons of mouse Apoa2. We amplified each of the four exons with PCR with the same protocol as shown above except using an annealing temperature of 59°C instead of 55°C, and checked the product sizes on 4% Nusieve 3:1 agarose gels. The PCR products were sequenced using Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Chemistry and the ABI 3700 Sequence Detection System.

Retrieving Data

We retrieved plasma HDL concentrations of the 43 inbred mouse strains from Mouse Phenome Database. Mice had been fed LabDiet 5K52 (6% fat) and were fasted for four hours before their blood was sampled. After precipitating non-HDL cholesterol with polyethylene glycol (20% PEG 8000 in 0.2 M glycine), plasma HDL concentrations were measured with Beckman Coulter Synchron CX5 chemistry analyzer.

APOA2 protein sequences of human, chimpanzee, monkey, cattle, pig, and rat were obtained from GenBank, and D. Puppione (UCLA, Los Angeles, CA) kindly provided horse APOA2 sequence.

Analyzing Statistical Difference

Student's t-test was used to compare the plasma HDL concentrations among the different groups.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Program for Genomic Applications of the Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (HL66611), NIH RO1 (HL074086 to X.W.), and the Scientist Development Grant of American Heart Association (AHA 0430381N to X.W.). We thank Eric Taylor and Christina Petros for their excellent technical assistance, Donald Puppione for sharing his unpublished data, and Ray Lambert for helping to prepare the manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org. The following individuals kindly provided reagents, samples, or unpublished information as indicated in the paper: D. Puppione.]

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.2668204. Article published online ahead of print in August 2004.

References

- Anunciado, R.V., Ohno, T., Mori, M., Ishikawa, A., Tanaka, S., Horio, F., Nishimura, M., and Namikawa, T. 2000. Distribution of body weight, blood insulin and lipid levels in the SMXA recombinant inbred strains and the QTL analysis. Exp. Anim. 49: 217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biola, O., Angel, J.M., Avner, P., Bachmanov, A.A., Belknap, J.K., Bennett, B., Blankenhorn, E.P., Blizard, D.A., Bolivar, V., Brockmann, G.A., et al. 2003. The nature and identification of quantitative trait loci: A community's view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4: 911-916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Vaca, F., Escola-Gil, J.C., Martin-Campos, J.M., and Julve, J. 2001. Role of apoA-II in lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis: Advances in the study of an enigmatic protein. J. Lipid Res. 42: 1727-1739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden, W.E. and Pearson, T.A. 2000. Raising low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is an important target of therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 85: 645-650, A610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colinayo, V.V., Qiao, J.H., Wang, X., Krass, K.L., Schadt, E., Lusis, A.J., and Drake, T.A. 2003. Genetic loci for diet-induced atherosclerosis lesions and plasma lipids in mice. Mamm. Genome 14: 464-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dansky, H.M., Charlton, S.A., Sikes, J.L., Heath, S.C., Simantov, R., Levin, L.F., Shu, P., Moore, K.J., Breslow, J.L., and Smith, J.D. 1999. Genetic background determines the extent of atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19: 1960-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, M.H., LeBoeuf, R.C., Warden, C.H., Bee, L.M., and Lusis, A.J. 1990. A polymorphism affecting apolipoprotein A-II translational efficiency determines high-density lipoprotein size and composition. J. Biol Chem. 265: 16380-16388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbein, S.C. and Hasstedt, S.J. 2002. Quantitative trait linkage analysis of lipid-related traits in familial type 2 diabetes: Evidence for linkage of triglyceride levels to chromosome 19q. Diabetes 51: 528-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesen, K., Plum, L., Kluge, R., Ortlepp, J., and Joost, H.G. 2003. Diet-dependent obesity and hypercholesterolemia in the New Zealand obese mouse: Identification of a quantitative trait locus for elevated serum cholesterol on the distal mouse chromosome 5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 304: 812-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazier, A.M., Nadeau, J.H., and Aitman, T.J. 2002. Finding genes that underlie complex traits. Science 298: 2345-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, L., Johnson, M.W., and Lusis, A.J. 1999. Quantitative trait locus analysis of plasma lipoprotein levels in an autoimmune mouse model: Interactions between lipoprotein metabolism, autoimmune disease, and atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19: 442-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, K., Kitagawa, K., Naiki, H., Hanada, K., Hosokawa, M., and Takeda, T. 1991. Polymorphism of apolipoprotein A-II (apoA-II) among inbred strains of mice. Relationship between the molecular type of apoA-II and mouse senile amyloidosis. Biochem. J. 279: 427-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimori, N., Li, R., Kelmenson, P.M., Korstanje, R., Walsh, K.A., Churchill, G.A., Forsman-Semb, K., and Paigen, B. 2004. Quantitative trait loci analysis for plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations and atherosclerosis susceptibility between inbred mouse strains C57BL/6J and 129S1/SvImJ. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 161-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa, K., Wang, J., Mastushita, T., Kogishi, K., Hosokawa, M., Fu, X., Guo, Z., Mori, M., and Higuchi, K. 2003. Polymorphisms of mouse apolipoprotein A-II: Seven alleles found among 41 inbred strains of mice. Amyloid 10: 207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korstanje, R. and Paigen, B. 2002. From QTL to gene: The harvest begins. Nat. Genet. 31: 235-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korstanje, R., Li, R., Howard, T., Kelmenson, P., Marshall, J., Paigen, B., and Churchill, G. 2004. Influence of sex and diet on quantitative trait loci for HDL cholesterol levels in an SM/J by NZB/BlNJ intercross population. J. Lipid Res. 45: 881-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.A., Wittenburg, H., Li, R., Walsh, K.A., Churchill, G.A., Carey, M.C., and Paigen, B. 2003. Quantitative trait loci that determine lipoprotein cholesterol levels in DBA/2J and CAST/Ei inbred mice. J. Lipid Res. 44: 953-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.A., Korstanje, R., Li, R., Walsh, K.A., Churchill, G.A., Carey, M.C., and Paigen, B. 2004a. Genetic contributors to lipoprotein cholesterol levels in an intercross of 129S1/SvImJ and RIIIS/J inbred mice. Physiol. Genomics 17: 114-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.A., Wittenburg, H., Li, R., Walsh, K.A., Korstanje, R., Churchill, G.A., Carey, M.C., and Paigen, B. 2004b. Quantitative trait loci that determine lipoprotein cholesterol levels in an intercross of 129S1/SvImJ and CAST/Ei inbred mice. Physiol Genomics 17: 60-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machleder, D., Ivandic, B., Welch, C., Castellani, L., Reue, K., and Lusis, A.J. 1997. Complex genetic control of HDL levels in mice in response to an atherogenic diet. Coordinate regulation of HDL levels and bile acid metabolism. J. Clin. Invest. 99: 1406-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manenti, G., Galbiati, F., Gianni-Barrera, R., Pettinicchio, A., Acevedo, A., and Dragani, T.A. 2004. Haplotype sharing suggests that a genomic segment containing six genes accounts for the pulmonary adenoma susceptibility 1 (Pas1) locus activity in mice. Oncogene 23: 4495-4504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, M., Qiao, J.H., Hyman, R., Ruddle, D., Laughton, C., and Lusis, A.J. 1993. Influence of the apoA-II gene locus on HDL levels and fatty streak development in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 13: 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, M., Castellani, L.W., Wen, P.Z., Wong, J., Rithaporn, T., Hama, S.Y., Hough, G.P., Johnson, D., Albers, J.J., Mottino, G.A., et al. 2000. Genetic control of HDL levels and composition in an interspecific mouse cross (CAST/Ei×7BL/6J). J. Lipid Res. 41: 1936-1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau, J.H. and Frankel, W.N. 2000. The roads from phenotypic variation to gene discovery: Mutagenesis versus QTLs. Nat. Genet. 25: 381-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, G.P., George, V., Go, R.C., Page, P.Z., and Allison, D.B. 2003. “Are we there yet?”: Deciding when one has demonstrated specific genetic causation in complex diseases and quantitative traits. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73: 711-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.G., Clifford, R., Buetow, K.H., and Hunter, K.W. 2003. Multiple cross and inbred strain haplotype mapping of complex-trait candidate genes. Genome Res. 13: 118-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell-Huynh, D.A., Weinreb, A., Castellani, L.W., Mehrabian, M., Doolittle, M.H., and Lusis, A.J. 1995. Genetic factors in lipoprotein metabolism. Analysis of a genetic cross between inbred mouse strains NZB/BINJ and SM/J using a complete linkage map approach. J. Clin. Invest. 96: 1845-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, M., Davis, D.L., Vick, B.R., and Russell, D.W. 2001. Genetic analysis of cholesterol accumulation in inbred mice. J. Lipid Res. 42: 1812-1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehayek, E., Duncan, E.M., Yu, H.J., Petukhova, L., and Breslow, J.L. 2003. Loci controlling plasma non-HDL and HDL cholesterol levels in a C57BL /6J×CASA /Rk intercross. J. Lipid Res. 44: 1744-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shike, T., Hirose, S., Kobayashi, M., Funabiki, K., Shirai, T., and Tomino, Y. 2001. Susceptibility and negative epistatic loci contributing to type 2 diabetes and related phenotypes in a KK/Ta mouse model. Diabetes 50: 1943-1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto, J. and Sekikawa, K. 2003. Quantitative trait locus analysis of plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels in KK×RR F2 mice. Biochem. Genet. 41: 325-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto, J., Matsuura, S., Yamanaka, H., and Sekikawa, K. 1999. Quantitative trait loci that regulate plasma lipid concentration in hereditary obese KK and KK-Ay mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1453: 385-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade, C.M., Kulbokas III, E.J., Kirby, A.W., Zody, M.C., Mullikin, J.C., Lander, E.S., Lindblad-Toh, K., and Daly, M.J. 2002. The mosaic structure of variation in the laboratory mouse genome. Nature 420: 574-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. and Paigen, B. 2002. Quantitative trait loci and candidate genes regulating HDL cholesterol: A murine chromosome map. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22: 1390-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Le Roy, I., Nicodeme, E., Li, R., Wagner, R., Petros, C., Churchill, G.A., Harris, S., Darvasi, A., Kirilovsky, J., et al. 2003. Using advanced intercross lines for high-resolution mapping of HDL cholesterol quantitative trait loci. Genome Res. 13: 1654-1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden, C.H., Fisler, J.S., Pace, M.J., Svenson, K.L., and Lusis, A.J. 1993. Coincidence of genetic loci for plasma cholesterol levels and obesity in a multifactorial mouse model. J. Clin. Invest. 92: 773-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch, C.L., Bretschger, S., Latib, N., Bezouevski, M., Guo, Y., Pleskac, N., Liang, C.P., Barlow, C., Dansky, H., Breslow, J.L., et al. 2001. Localization of atherosclerosis susceptibility loci to chromosomes 4 and 6 using the Ldlr knockout mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 7946-7951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire, T., Pletcher, M.T., Batalov, S., Barnes, S.W., Tarantino, L.M., Cooke, M.P., Wu, H., Smylie, K., Santrosyan, A., Copeland, N.G., et al. 2003. Genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis defines haplotype patterns in mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 3380-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEB SITE REFERENCES

- http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus; Mouse Genome Server at the Sanger Institute.

- http://www.jax.org/dnares/index.html; Mouse DNA Resource at the Jackson Laboratory.

- http://informatics.jax.org; Mouse Genome Informatics at the Jackson Laboratory.

- http://www.jax.org/phenome; Mouse Phenome Database at the Jackson Laboratory.