This study evaluated the feasibility of conducting a randomized sham-controlled trial and collected preliminary data on safety and efficacy of acupuncture. The study supports the finding that a sham-controlled randomized trial evaluating acupuncture in dysphagia-related quality of life in head and neck cancer is feasible and safe. Further investigation is required to evaluate efficacy.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Chemoradiation, Head and neck cancers, Dysphagia, Quality of life

Abstract

Introduction.

Dysphagia is common in head and neck cancer patients after concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CRT). This study evaluated the feasibility of conducting a randomized sham-controlled trial and collected preliminary data on safety and efficacy of acupuncture.

Patients and Methods.

Head and neck cancer (HNC) patients with stage III–IV squamous cell carcinoma were randomized to 12 sessions of either active acupuncture (AA) or sham acupuncture (SA) during and following CRT. Patients were blinded to treatment assignment. Swallowing-related quality of life (QOL) was assessed using the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) total and subscale scores.

Results.

Multiple aspects of trial feasibility were confirmed. Forty-two of 196 patients screened (21%) were enrolled and randomized to receive AA (n = 21) or SA (n = 21); 79% completed at least 10 of 12 planned acupuncture sessions; 81% completed the study follow-ups. The majority of patients reported uncertainty regarding their treatment assignment, with no difference between the AA and SA groups. Audits confirmed both AA and SA treatments were delivered with high fidelity. No serious acupuncture-related side effects were observed. MDADI total scores significantly improved from baseline to 12 months post-CRT in both groups (AA: +7.9; SA +13.9; p = .044, p < .001). Similar patterns were observed for the MDADI global subscale (AA: +25.0; SA +22.7; p = .001, p = .002). Intent-to-treat analyses suggested no difference between the treatment groups (p = .17, p = .76 for MDADI total and global scores, respectively).

Conclusion.

A sham-controlled randomized trial evaluating acupuncture in dysphagia-related QOL in HNC found the procedure to be feasible and safe. Further investigation is required to evaluate efficacy.

Implications for Practice:

Dysphagia or swallowing difficulty is an important and common condition after concurrent chemoradiation therapy in head and neck cancer patients. In addition to current available supportive care, acupuncture may offer potential for treating dysphagia. This study demonstrated that both active acupuncture and sham acupuncture are safe and were associated with improved dysphagia-related quality of life from baseline to 12 months after concurrent chemoradiation therapy. This study was not designed to inform underlying specific versus nonspecific effects. Future larger-scale pragmatic clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of acupuncture versus standard of care are warranted, and further mechanistic research is needed to understand how active versus purportedly sham acupuncture procedures affect dysphagia-related symptoms.

Abstract

摘要

引言. 吞咽困难在接受同步化放疗 (CRT) 的头颈癌患者中很常见。本研究评价了随机假对照临床试验的可行性, 并且收集了针刺治疗安全性和有效性的初步数据。

患者与方法. 对III∼IV期头颈鳞癌 (SCCHN) 患者在CRT期间和之后随机给予12个疗程的针刺治疗 (AA) 或假针刺治疗 (SA) 。患者对治疗分配不知情。使用MD安德森吞咽困难量表 (MDADI) 评估吞咽相关生活质量 (QoL) 总评分和分量表评分。

结果. 我们确认了临床试验的多方面可行性。共筛查196例患者, 42例 (21%) 入选, 随机给予AA (n=21) 或SA (n=21) 治疗。79%的患者至少完成了计划12个针刺疗程中的10个疗程, 81%完成了所有研究随访。大多数患者报告不清楚自己的治疗分组, AA和SA组间无差异。经审查确认AA和SA治疗的实施均具有很高的逼真度。研究未观察到严重针刺相关性不良事件。两组患者基线至CRT后12个月的MDADI总分均显著改善 (AA组: +7.9, SA: +13.9 ; P=0.044, P<0.001) 。MDADI分量表整体评分显示出类似的改善 (AA组: +25.0, SA: +22.7 ; P=0.001, P=0.002) 。意向性治疗分析提示治疗组间无差异 (MDADI总分和整体评分分别为P=0.17和P=0.76) 。

结论. 采用假对照随机临床试验来评价针刺治疗用于头颈癌患者吞咽困难相关性QoL是可行和安全的。需要开展进一步调查以评价有效性。The Oncologist 2016;21:1522–1529

对临床实践的提示: 对于头颈癌患者, 吞咽困难是同步化放疗后的重要和常见问题。除了目前可用的支持治疗外, 针刺在治疗吞咽困难中可能也具有潜力。本研究证实真针刺治疗和假针刺治疗均安全, 且可改善基线至同步化放疗后12个月的吞咽困难相关性生活质量。本研究的设计的目的不包括提供潜在特异性和非特异性作用信息。未来需要开展大型实用性临床试验以评价针刺治疗和标准治疗的有效性, 还需要开展进一步的机制研究以明确真实的针刺以及据信的假针刺操作对吞咽困难相关症状的影响。

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) refers to a group of cancers that arise in the oral and nasal cavities, sinus, salivary glands, pharynx, and larynx. The current standard of care for advanced HNC is concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CRT), which has led to increased survival rates, but with significant acute and long-term toxicities. Dysphagia, or difficulty with swallowing, is a common and expected side effect during and following CRT. Dysphagia occurs in up to 50% of patients and significantly impairs the quality of life (QOL) of patients during delivery of and recovery from CRT [1]. HNC patients can be feeding tube dependent (e.g., percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG] tube) for many months after CRT. Swallowing-related QOL often fails to improve in the period of 12 months after CRT [2]. Even with prophylactic swallowing exercises and nutritional support, dysphagia is prominent. Moreover, few prospective clinical trials specifically evaluating therapies for swallowing-related QOL have been reported. Thus, clinical trials evaluating promising and innovative adjunctive approaches that could increase the rate and magnitude of recovery from dysphagia in HNC patients are needed.

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese medical technique that has been found to reduce symptoms and side effects associated with primary cancer therapy [3–5]. More recently, research has begun to evaluate the efficacy and underlying mechanisms through which acupuncture may reduce dysphagia, including in HNC patients [6, 7]. In addition, we have previously reported a case series (n = 10) of HNC patients using acupuncture for dysphagia that demonstrated acupuncture is well tolerated and associated with a shorter PEG tube duration compared with historical controls [8].

This pilot study was designed with three related goals to help inform a future, more definitive trial of acupuncture for swallowing-related QOL in HNC patients receiving CRT: (1) to evaluate trial feasibility; (2) to evaluate the safety of the acupuncture protocols; and (3) to collect preliminary data on the efficacy of acupuncture for dysphagia-related QOL and to estimate person-to-person variation in dysphagia-related QOL in this population to estimate the sample size needed for an adequately powered future randomized trial.

Materials and Methods

Details of the study design have been reported elsewhere and are briefly summarized here [9].

Patients

Participants were recruited through the HNC program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI). Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, stage II, III, and IV, without distant metastases; were receiving curative-intent concurrent CRT, with or without neck dissection; and were already undergoing swallowing therapy and nutritional support. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was used in the study population. Exclusion criteria included patients with a history of neurologic dysphagia including stroke, neurodegenerative disease and advanced dementia; uncontrolled seizure disorder; unstable cardiac disease or myocardial infarction within 6 months before study entry; wearing a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; and prior use of acupuncture for dysphagia. All acupuncture (active and sham) was administered at the Leonard P. Zakim Center for Integrative Therapies, DFCI. All participants signed an informed consent before randomization. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Harvard Medical School and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, registered at clinical trials.gov (identifier: NCT00797732), and conducted between January 2009 and January 2013.

Acupuncture Interventions

This pilot study was a two-arm sham-controlled randomized trial. Treatment assignments (active or sham acupuncture) were generated by the study statistician using a permuted block design with randomly varying block size. All study patients and research personnel (except the treating acupuncturists) were blinded to the randomized treatment assignments. Both active and sham acupuncture were administered by 5 experienced staff acupuncturists employing a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) style, once every 2 weeks for 24 weeks, starting 2 weeks into CRT and ending at 20 weeks after CRT.

Active Acupuncture

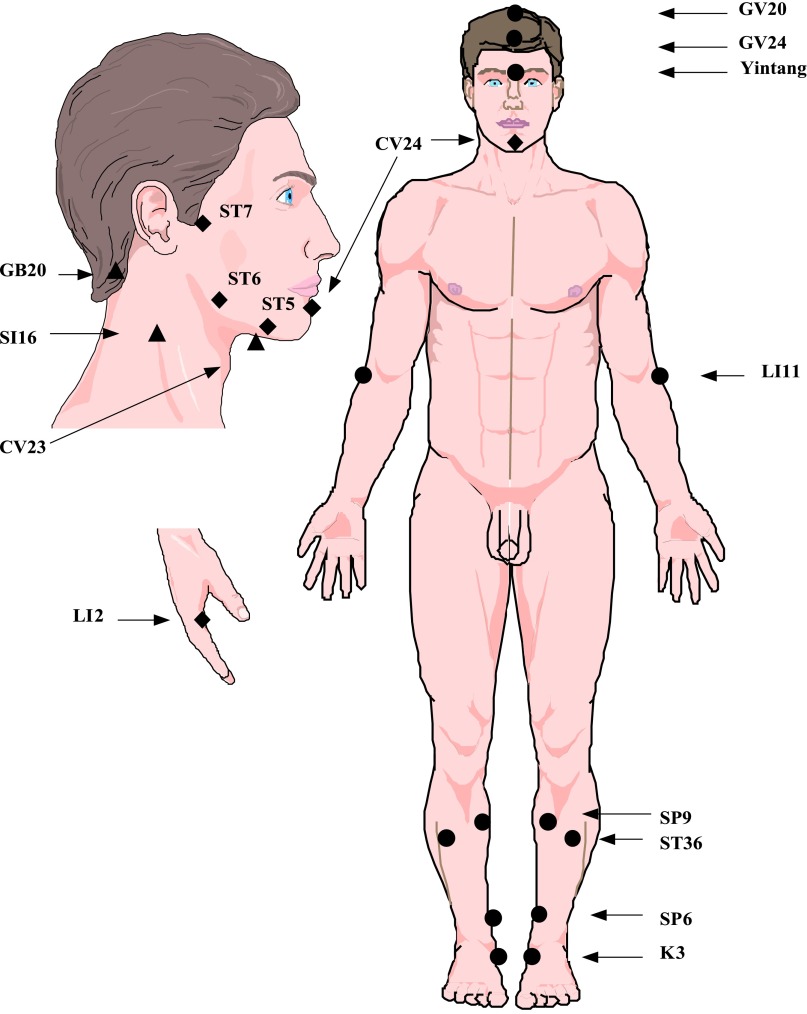

As described in detail previously, the active intervention used a three-phase step-up protocol to gradually increase the body areas treated and needling intensity [9]. The choice of acupuncture points was determined based on a systematic literature review [9] following the STRICTA guideline [10]. Acupuncture needles (Vinco, 0.20 × 25 mm; Helio USA Inc., San Jose, CA, http://www.heliomed.com) were inserted into predefined acupuncture points (ST36, SP9, K3, LI11, GV20, GV24, Yintang, LI2, ST7, ST5, CV24, SI16, GB20, CV23) (Fig. 1), with a depth of 5–10 mm, and needles were stimulated to obtain the de qi sensation. An electroacupuncture (EA) device (AWQ-104L; Lhasa OMS, Inc., Weymouth, MA, USA, http://www.lhasaoms.com) was connected at two acupoints (GV20 and Yintang; continuous 4 Hz, 350 µs pulse-width). All needles remained in place for 30 minutes.

Figure 1.

Acupuncture points used for chemoradiation-related dysphagia in head and neck cancer. To avoid the radiation field, acupuncture points needled before week 4 after CRT (phase 1, solid round circles) were selected to avoid the chin and neck area. Additional points were added at week 4 after CRT visit (phase 2, solid diamonds) and at the week 12 after CRT (phase 3, solid triangles). Electrostimulation was added starting with the third visit.

Abbreviation: CRT, chemoradiation therapy.

Sham Acupuncture

The sham intervention was designed to be maximally inert and minimally invasive, while simulating most aspects of the active protocol. Very thin acupuncture needles (no. 02; 0.12 mm × 30 mm; Seirin, Weymouth, MA, USA, http://www.seirinamerica.com) were used as sham needles. Needle insertion was limited to a depth between 0.2 mm and 0.5 mm, with no manipulation. Sham needles were inserted at 14 locations paralleling the same body regions needled in the active group; however, all sham point locations were off the pathways of traditional Chinese medicine acupuncture meridians and points [9]. An identical but deactivated EA device was used following sham protocols previously used [11].

Assessment of Trial Feasibility and Safety

The feasibility of conducting a randomized sham-controlled acupuncture trial for HNC patients was evaluated by assessing the following: (1) the proportion of screened patients who were eligible and willing to be enrolled in, and completed, the study; (2) treatment compliance recorded by clinicians as attendance at acupuncture sessions; (3) outcome protocol compliance assessed by study staff as attendance and completion of assessments; (4) blinding and expectancy assessed through self-administered questionnaires; and (5) fidelity of treatment delivery both through an analysis of protocol checklists completed by acupuncturists following the delivery of each treatment, and through patient reported stimulation intensities assessed using an acupuncture sensation scale developed for this study [9]. Our predefined criteria for feasibility were (1) at least 75% of participants completing at least 80% of interventions, and (2) at least 80% of participants in each group completing all study evaluations [9].

The success of patient blinding was assessed after the second and final acupuncture treatments with a self-administered instrument used in prior acupuncture trials [11]. Patients’ expectancy regarding the efficacy of acupuncture for treating dysphagia was assessed using self-administered treatment credibility scale (3–15, 15 = highest expectancy) [11]. Safety of the acupuncture intervention was evaluated using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE 3.0) at each visit.

Outcome Measures

All outcome measures were assessed by a clinical research coordinator blinded to treatment assignment. The primary clinical outcomes were changes in QOL as measured by the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) from baseline to 12 months after CRT (6 months after acupuncture treatment). Additional clinical outcome measures included changes in MDADI scores at 20 weeks after CRT.

The MDADI is a validated, self-administered questionnaire, and it is considered the best measure of QOL in HNC patients with high reliability and sensitivity (Cronbach α = 0.85–0.93). It has been used in a number of prior studies [12–14] and characterizes how patients view their swallowing ability as a result of treatment and how the swallowing dysfunction affects their QOL. The MDADI has been used to track the longitudinal course of individual patient’s outcomes [14, 15]. The MDADI has four subscales––global, emotional, physical, and functional––to characterize the effects of dysphagia on different aspects of QOL. There are 5 possible responses to each of the MDADI questions (strongly agree, agree, no opinion, disagree, and strongly disagree) and answers are scored on a scale of 1–5. The global score is a single-item overall assessment of how QOL has been impacted by swallowing difficulty, and it is scored separately from the other three subscales. The emotional, functional, and physical subscales include multiple items that are averaged to form a composite MDADI total score. Subscales are then multiplied by 20, and a composite total score ranges from 20–100, with 20 being low-functioning and 100 being high functioning. Scoring of two questions (E7 and F2) are reversed accordingly to the methodology of Carlsson [13].

Statistical Analysis and Sample Size Calculation

Sample size calculations were based on the MDADI, assuming a difference of 20 points as clinically significant, a standard deviation of change of 17.1 points in MDADI [16] and allowing for a 20% loss to follow-up. We originally estimated that a sample size of 18 per treatment group would provide 85% power to detect a 20-point difference between the AA and the SA. After six participants had been enrolled, a protocol modification was made to address recruitment challenges. A revised protocol targeted patients much earlier in their course of treatment (i.e., 2 weeks into CRT vs. 12 weeks after CRT) and decreased the frequency of acupuncture treatments (i.e., from once per week to once every 2 weeks). Both protocols ended at 20 weeks after CRT. After these protocol modifications, an additional 36 patients using the new protocol were enrolled, for a final sample size of 42.

All analyses were conducted using the intention-to-treat principle. QOL data were analyzed by repeated-measures mixed models adjusting for baseline differences and the versions of the study protocol. Individual missing items in multi-item scales were handled as recommended by the scale developers. Categorical data were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. Participants who attended at least 10 sessions (80%) of the target of 12 treatments were a priori defined as protocol compliant. A post hoc exploratory analysis limited to fully compliant patients evaluated outcomes following all 12 prescribed treatments. A 2-sided p value of .05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS, Cary, NC, USA, http://www.sas.com).

Results

Participant Flow and Baseline Characteristics

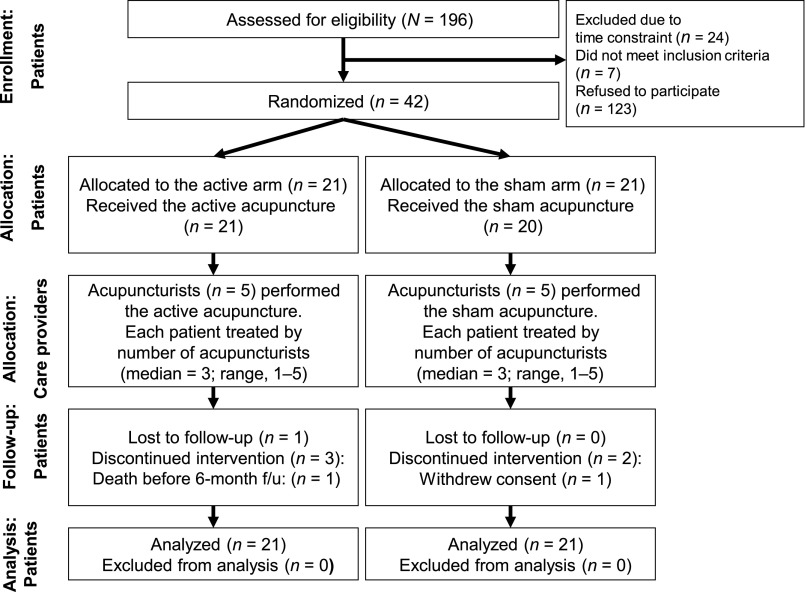

Participants were enrolled from January 2009 through December 2011. Figure 2 shows the flow of participants through the trial. Of the 196 potentially eligible patients approached, 42 (21%) were eligible and agreed to participate. The most common reason for exclusion was refusal to participate, primarily due to time constraints. Of the 42 patients randomized, 1 patient in the SA arm withdrew consent right after being randomized and before acupuncture began. In addition, five patients withdrew during the study due to time constraints. Withdrawals were evenly distributed in the AA arm (n = 3) and the SA arm (n = 3). Among the remaining 36 patients, 1 patient died during the follow-up period (AA arm) and 1 patient did not provide last assessment data (AA arm). Therefore, 34 completed the study and provided end-of-treatment QOL data (16 patients in the AA, 18 in the SA). Thirty-three (79%) patients completed at least 10 acupuncture sessions including 16 (77%) patients in the AA arm and 17 (81%) in the SA arm. Overall, the number of patients who completed assessments at baseline, 20 weeks after CRT, and 12 months after CRT were 36 (86%), 35 (83%), and 34 (81%), respectively.

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram of acupuncture trial for chemoradiation-related dysphagia in head and neck cancer.

Abbreviation: CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; f/u, follow-up.

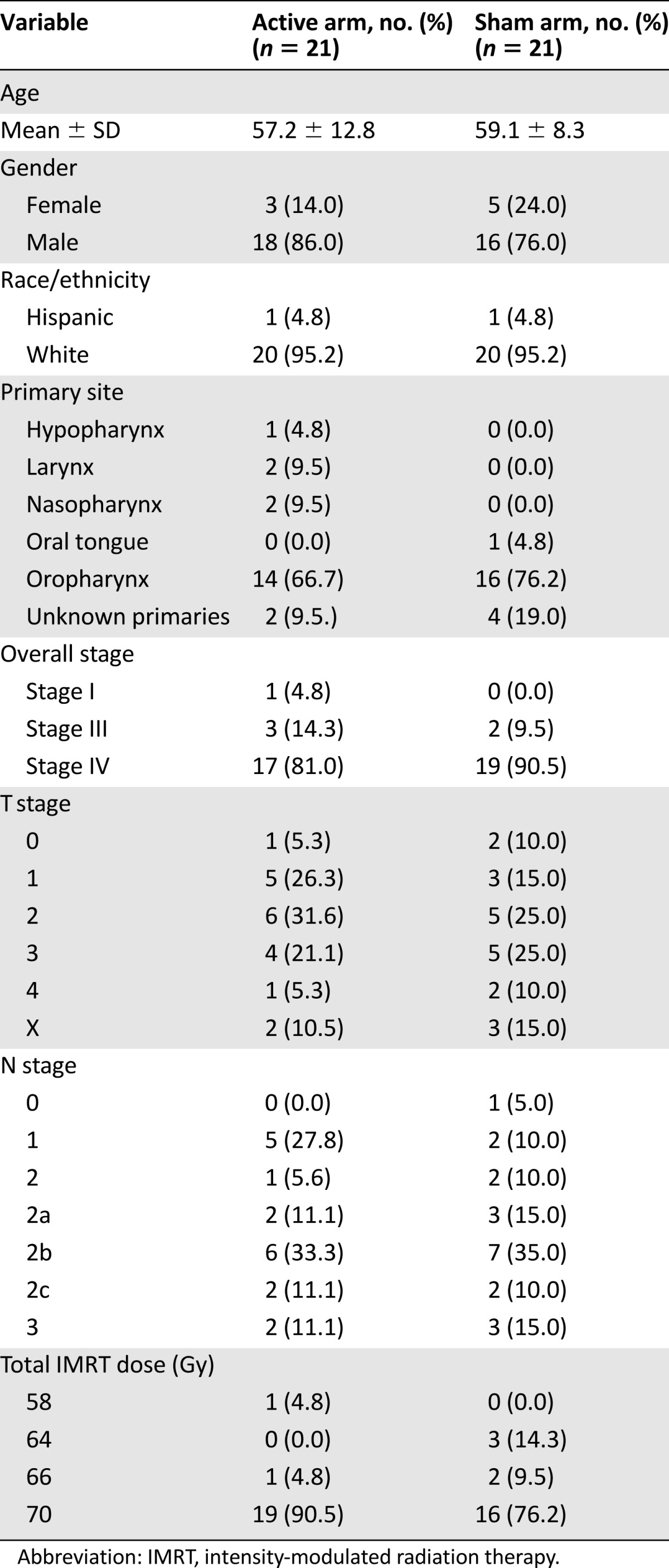

Table 1 presents the demographic and tumor characteristics of the study patients. At baseline, the AA arm and the SA arm shared similar demographic and clinical characteristics. No significant difference was found between groups with regard to patient’s age, gender, race, and tumor sites and stages. However, the proportion of patients who received 70 Gy radiation doses were noticeably higher in the AA arm than that in the SA arm (90% vs. 76%), a potentially important imbalance between the 2 arms.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 42)

Participant Blinding and Expectancy

After 2 acupuncture sessions, 71% of subjects in the AA arm and 68% in the SA arm indicated they were not certain whether they were receiving the AA or the SA. Only 24% in the AA arm and 5% in the SA arm correctly guessed their assignment. Responses to the blinding questionnaire did not differ by actual treatment assignment (p > .99). After completing all treatments, 59% of participants remained unsure of their treatment assignment, but of the 14 participants who guessed a treatment, 79% were correct (6 of 8 in the AA group and 5 of 6 in the SA group). Overall, the responses did not differ by treatment assignment (p = .11). At baseline, all participants indicated high and equal level of expectancy (i.e., all were very optimistic) that acupuncture might be effective in treating dysphagia (median of 12 in the AA and 13 in the SA arm on a 3–15 scale).

Fidelity of Treatment Delivery by Acupuncturists

Among 50 case report forms audited, 48 (96%) followed the protocol for acupuncture point placement. The mean acupuncture sensation intensity scores were significantly greater in the AA arm versus SA arm (3.39 ± 0.21 vs. 0.39 ± 0.22; p < .001, on a 0–10 scale), indicating active acupuncture (AA) treatments were appropriately and reliably delivered.

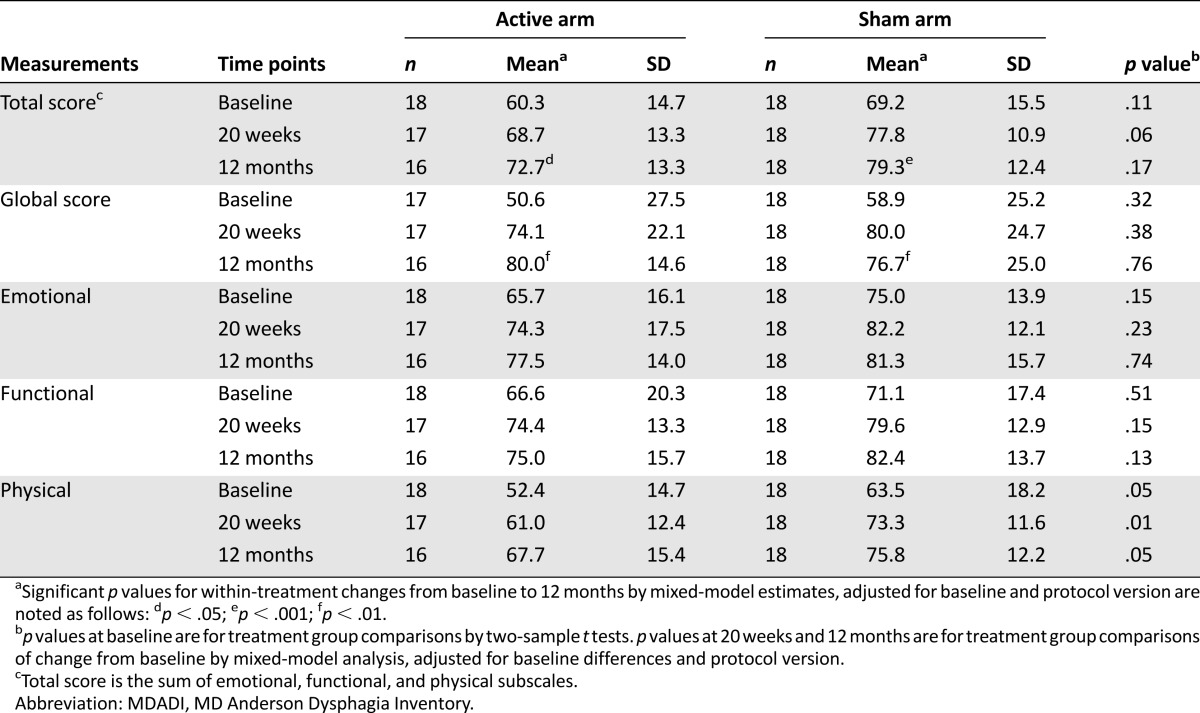

Outcomes of MDADI

Table 2 presents unadjusted summary statistics and p values from adjusted analyses of the total MDADI score and the four MDADI subscales (global, emotional, functional, physical) assessed at baseline and each follow-up time point.

Table 2.

MDADI scores (unadjusted) by treatment group and tests of treatment difference (adjusted)

Baseline values for the Total MDADI Score were lower in the AA versus the SA arm (p = .11). Total scores significantly increased from baseline to 12 months in both the AA and SA groups (p = .044 and p < .001, respectively), with no significant difference between the AA group (+7.9 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.2–15.6 points, adjusted) versus the SA group (+13.9 points; 95% CI, 6.4–21.4, adjusted); p = .17 for the between-group comparison (95% CI, -14.7–2.7; standard error = 4.3). Similar estimates were obtained from post hoc analyses limited to patients in both groups that completed all 12 treatments (+5.9 vs. +11.5 for AA vs. SA groups; p = .26).

Baseline scores for all MDADI subscales were higher in the SA group as compared with those in the AA group, but only the difference in the physical subscale was statistically significant (p = .05). At 12 months after CRT, the global score significantly increased from baseline in both groups (+25.0; 95% CI, 10.6–39.5; p = .001 in AA group vs. +22.7; 95% CI, 8.6–36.9; p = .002 in the SA group, adjusted). The magnitude of improvement did not differ between groups (95% CI, -12.5–17.1; p = .76). Post hoc analysis of MDADI global scores limited to patients in both groups that completed all 12 treatments suggested no treatment difference (95% CI, -11.5–23.6; p = .49). Between-group differences in 12-month change in emotional, functional, and physical subscales favored participants in the SA group (p = .74, .13, and .053, respectively).

The standard error for the between-group comparison of 12-month change in MDADI total score of 4.3 points implies an effective standard deviation of 13.9 points (= 4.3 × sqrt(1 / (1/21 + 1/21))), incorporating effects of loss to follow-up. Given this estimate, a sample size of n = 42 randomized 1:1 provides 80% power to detect a treatment difference of 12.3 points based on a 2-sided test at α = 0.05.

Adverse Events

Only 1 occurrence of a minor needling site bruise (grade 1) was reported (in the AA group) resulting in an incidence rate of 2.4% (1 of the 41 patients who received either AA or SA treatment).

Discussion

Despite the prevalence and personal and public health burden of HNC, few controlled clinical trials have evaluated therapies that target QOL improvement in this population. Our pilot study represents the first randomized sham-controlled trial to evaluate the benefits of acupuncture for swallowing-related QOL in HNC patients during and after concurrent CRT. Our primary findings are that (1) a sham-controlled acupuncture trial for HNC patients undergoing active CRT is feasible; (2) acupuncture treatment during chemoradiation for HNC patients is safe with few reported adverse effects; and (3) QOL assessed with the MDADI total score and MDADI global subscale improved with exposure to both AA and SA. Collectively, these findings support the value of future larger-scale pragmatic clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of acupuncture versus standard of care dysphagia related QOL in HNC patients. Our findings also highlight the need for further mechanistic research to better understand how active versus purportedly sham acupuncture procedures affect dysphagia related symptoms.

Our pilot study confirmed multiple aspects of trial feasibility. Our 21% recruitment rate and 19% loss to follow-up are comparable with other recently published trials in HNC conducted in other academic medical centers [3]. Recruitment of HNC patients who are receiving concurrent CRT is challenging as they have significantly higher symptom severity and lower QOL than HNC patients who are receiving radiation therapy alone, and these symptoms worsen during treatment [17]. We demonstrated that AA and SA treatments could be delivered in a blinded fashion, although further efforts to enhance treatment concealment would be helpful. Such findings are critical as prior studies have shown that lack of blinding and imbalances in treatment expectation can markedly bias responses to active versus sham treatments [18].

Our results also demonstrated that it was safe to perform acupuncture in patients who were receiving intense concurrent chemoradiation therapy and subsequent follow-up, with only infrequent and mild local bruising reported as an adverse experience.

Our original study design was based on a personal communication with one of the developers of MDADI who suggested a 20-point difference was clinically relevant; however, a validated minimally important difference for MDADI has not yet been determined. Ringash et al. suggest that a 5%–10% in QOL is a benchmark for patient-reported outcomes in laryngeal cancer patients [19]. Similarly, Osoba and King suggest that a 15% change indicates a relatively large change in QOL [20, 21]. With an average baseline MDADI total score in our sample of 64 points, a 10% change would be approximately 6 points. Based on these and other studies published to date, our observed changes in both the MDADI total score (13% in AA) and MDADI global subscale (51% in AA) are in line with reports of equivalent changes in QOL that have been interpreted as clinically relevant.

Our pilot study was not designed to have adequate statistical power to test a 10% difference between verum acupuncture’s efficacy and a sham acupuncture control. Our findings suggest that in HNC patients treated with definitive CRT, dysphagia-related QOL improved after receiving both AA and SA. Similar findings of large effects of sham acupuncture, which are statistically indistinguishable from active acupuncture treatments, have been reported in other cancer studies [4, 5]. The results of our study should be interpreted in relation to our patient population and the cancer therapies they received. Our study population mainly consisted of HNC patients with stage IV diseases (>80%) who went through concurrent CRT with high-dose radiation (70 Gy), thus representing a very advanced HNC population. Recent studies suggest that this population of HNC patients do not exhibit significant improvement in MDADI scores at 12 months after CRT [14, 15, 22, 23]. This contrasts with longer-term observations of less advanced patients, among whom improvements have been reported after 22 months [12]. Dysphagia status is strongly associated with cancer stages, radiotherapy dose prescribed, and chemotherapy used [24]. It appears that, simply by chance, the proportion of study patients who received 70 Gy radiotherapy was markedly higher in the AA arm versus SA arm (90% vs. 76%) (Table 1), which may have influenced the lower improvement rate, as well as the lower baseline MDADI scores observed in the AA arm.

Based on these findings, and in thinking about the design of a future study, the choice of control intervention warrants careful consideration. In this study, we used a relatively conservative sham intervention that allowed for needle penetration into the skin but controlled for needle location and intensity of stimulation. Given the potentially large effect of the patient-practitioner relationship established during either sham or active acupuncture and the potential physiological effect of penetrating needling anywhere on the skin, future studies should consider inclusion of a wait-list, standard-of-care control group (WLC), in addition to a sham acupuncture intervention. Comparison of AA with a wait-list, nontreatment control would better estimate the pragmatic clinical benefits to QOL of adding acupuncture to standard CRT care, whereas comparison of AA with SA would allow for the testing of specific needling effects. With a baseline MDADI total score of 64, a 10% difference in improvement would be approximately 6 points. With our estimated standard error of 4.3 points, a sample size of 172 randomized 1:1 (n = 86 per group) would provide 80% power for a comparison of AA versus SA tested at 2-sided p < .05. A three-arm trial comparing AA versus SA versus WLC would require a sample size of 306 if randomized 1:1:1, assuming two coprimary comparisons (AA vs. SA and AA vs. WLC), each tested at p < .027 to maintain an overall 5% type I error rate by Dunnett’s method.

There are a number of limitations of this study. First, although we achieved good patient retention and compliance with acupuncture treatment, we had difficulty recruiting patients when attempting to enroll patients after they had completed radiation therapy. The primary reasons for patients’ refusal to participant were time constraints and travel distance. Many patients were eager to go home after the completion of radiation therapy. These challenges have been noted in other studies [25, 26]. Recruitment was improved by initiating acupuncture at the very beginning of CRT phase while patients were receiving daily radiation at the institution. As a small pilot study, we must be cautious in interpreting our observed trends. Estimates of treatment efficacy are imprecise. Second, and as discussed earlier, the use of a single sham acupuncture control group may have underestimated possible treatment benefits of active acupuncture. Considerable uncertainty remains regarding the physiological effects of acupuncture needling. It is possible that in the sham acupuncture group, needling was not entirely inert [27]. Future trials should consider a third, nonintervention arm that would allow a more meaningful estimate of the value of adding verum acupuncture to current clinical care. Blinding an acupuncture intervention is challenging as patients are aware of the procedure. Our study achieved a successful blinding rate of 59%, comparable with that of other sham-controlled acupuncture studies [28, 29]. It has been suggested that de qi, the needling sensation elicited by acupuncture, and other nonverbal clues, can unblind participants [29, 30]. In future studies, using devices such as retractable and double blinded sham needles may improve blinding. Finally, it is possible that the current study may have employed an inadequate dose of acupuncture which could also have led to an underestimate of the true benefit from active acupuncture. Compared with other cancer studies, treatment provided once every 2 weeks represents a very low frequency, and other studies have reported that more acupuncture sessions are associated with better outcomes [4, 5, 31]. Given the severity of concurrent CRT toxicity, a higher frequency of acupuncture sessions, for example, three times per week, should be considered in a future trial. This modification would likely require additional protocol changes to offset this increased burden, such as adding additional EA stimulating sites, modifying EA wave patterns, and altering the acupuncture points used.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Conclusion

A blinded, sham-controlled, randomized clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness of verum acupuncture in treating dysphagia-related QOL in patients with advanced stage of HNC undergoing intense CRT found the procedure to be feasible, safe, and well tolerated. Dysphagia-related QOL improved with both active acupuncture and sham acupuncture. A future, more definitive trial, is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant 1K01 AT004415 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Weidong Lu, Peter M. Wayne, Roger B. Davis, Julie E. Buring, Laura A. Goguen, David S. Rosenthal, Roy B. Tishler, Marshall R. Posner, Robert I. Haddad

Provision of study material or patients: Weidong Lu, Jochen H. Lorch, Elaine Burke, Tyler C. Haddad, Laura A. Goguen, Roy B. Tishler, Robert I. Haddad

Collection and/or assembly of data: Weidong Lu, Hailun Li, Elaine Burke, Tyler C. Haddad

Data analysis and interpretation: Weidong Lu, Peter M. Wayne, Julie E. Buring, Hailun Li, Eric A. Macklin

Manuscript writing: Weidong Lu, Peter M. Wayne, Julie E. Buring, Eric A. Macklin, David S. Rosenthal, Roy B. Tishler, Robert I. Haddad

Final approval of manuscript: Weidong Lu, Peter M. Wayne, Roger B. Davis, Julie E. Buring, Hailun Li, Eric A. Macklin, Jochen H. Lorch, Elaine Burke, Laura A. Goguen, David S. Rosenthal, Roy B. Tishler, Marshall R. Posner, Robert I. Haddad

Disclosures

Eric A. Macklin: Biotie Therapies, Inc. (RF), Acorda Therapeutics and Shire Human Genetic Therapies (SAB); Jochen H. Lorch: Novartis, Millennium (RF); Roy B. Tishler: EMD Serrono (C/A); Robert I. Haddad: Eisai, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Bayer, Benzyme (C/A). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Nguyen NP, Moltz CC, Frank C, et al. Dysphagia following chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:383–388. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauloski BR, Logemann JA, Rademaker AW, et al. Speech and swallowing function after oral and oropharyngeal resections: One-year follow-up. Head Neck. 1994;16:313–322. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880160404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfister DG, Cassileth BR, Deng GE, et al. Acupuncture for pain and dysfunction after neck dissection: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2565–2570. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao JJ, Xie SX, Farrar JT, et al. A randomised trial of electro-acupuncture for arthralgia related to aromatase inhibitor use. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao T, Cai L, Snyder C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in women with breast cancer enrolled in a dual-center, double-blind, randomized controlled trial assessing the effect of acupuncture in reducing aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms. Cancer. 2014;120:381–389. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou H, Zhang P. Effect of swallowing training combined with acupuncture on dysphagia in nasopharyngeal carcinoma after radiotherapy (in Chinese) Chinese J Rehab Theory Pract. 2006;12:58–59. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Liu ZS, Sun SC, et al. Study on mechanisms of acupuncture treatment for moderate-severe dysphagia at chronic stage of appoplexy. Zhonguo Zhen Jiu. 2002;22:405–407. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu W, Posner MR, Wayne P, et al. Acupuncture for dysphagia after chemoradiation therapy in head and neck cancer: A case series report. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9:284–290. doi: 10.1177/1534735410378856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu W, Wayne PM, Davis RB, et al. Acupuncture for dysphagia after chemoradiation in head and neck cancer: Rationale and design of a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:700–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, et al. STRICTA Revision Group Revised standards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (stricta): Extending the consort statement. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wayne PM, Krebs DE, Macklin EA, et al. Acupuncture for upper-extremity rehabilitation in chronic stroke: a randomized sham-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:2248–2255. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.07.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen AY, Frankowski R, Bishop-Leone J, et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: The MD Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsson S, Rydén A, Rudberg I, et al. Validation of the Swedish MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) in patients with head and neck cancer and neurologic swallowing disturbances. Dysphagia. 2012;27:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s00455-011-9375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson JA, Carding PN, Patterson JM. Dysphagia after nonsurgical head and neck cancer treatment: Patients’ perspectives. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:767–771. doi: 10.1177/0194599811414506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.More YI, Tsue TT, Girod DA, et al. Functional swallowing outcomes following transoral robotic surgery vs primary chemoradiotherapy in patients with advanced-stage oropharynx and supraglottis cancers. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:43–48. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillespie MB, Brodsky MB, Day TA, et al. Laryngeal penetration and aspiration during swallowing after the treatment of advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:615–619. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.7.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Fuller CD, et al. Patterns of symptom burden during radiotherapy or concurrent chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer: A prospective analysis using the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Symptom Inventory-Head and Neck Module. Cancer. 2014;120:1975–1984. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishop FL, Yardley L, Prescott P, et al. Psychological covariates of longitudinal changes in back-related disability in patients undergoing acupuncture. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:254–264. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ringash J, O’Sullivan B, Bezjak A, et al. Interpreting clinically significant changes in patient-reported outcomes. Cancer. 2007;110:196–202. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King MT. The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:555–567. doi: 10.1007/BF00439229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roe JW, Drinnan MJ, Carding PN, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following parotid-sparing intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. How important is dysphagia? Oral Oncol. 2014;50:1182–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson JM, McColl E, Carding PN, et al. Swallowing in the first year after chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer: Clinician- and patient-reported outcomes. Head Neck. 2014;36:352–358. doi: 10.1002/hed.23306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MD Anderson Head and Neck Cancer Symptom Working Group Beyond mean pharyngeal constrictor dose for beam path toxicity in non-target swallowing muscles: Dose-volume correlates of chronic radiation-associated dysphagia (RAD) after oropharyngeal intensity modulated radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118:304–314. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Molen L, van Rossum MA, Rasch CR, et al. Two-year results of a prospective preventive swallowing rehabilitation trial in patients treated with chemoradiation for advanced head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:1257–1270. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotz T, Federman AD, Kao J, et al. Prophylactic swallowing exercises in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiation: A randomized trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138:376–382. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2012.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langevin HM, Wayne PM, Macpherson H, et al. Paradoxes in acupuncture research: Strategies for moving forward. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:180805. doi: 10.1155/2011/180805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Xie SX, et al. Electroacupuncture versus gabapentin for hot flashes among breast cancer survivors: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3615–3620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vase L, Baram S, Takakura N, et al. Can acupuncture treatment be double-blinded? An evaluation of double-blind acupuncture treatment of postoperative pain. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takakura N, Yajima H. A double-blind placebo needle for acupuncture research. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacPherson H, Maschino AC, Lewith G, et al. Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration Characteristics of acupuncture treatment associated with outcome: An individual patient meta-analysis of 17,922 patients with chronic pain in randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]