Abstract

Two actin-dependent force generators contribute to mitochondrial inheritance: Arp2/3 complex and the myosin V Myo2p (together with its Rab-like binding partner Ypt11p). We found that deletion of YPT11, reduction of the length of the Myo2p lever arm (myo2-Δ6IQ), or deletion of MYO4 (the other yeast myosin V), had no effect on mitochondrial morphology, colocalization of mitochondria with actin cables, or the velocity of bud-directed mitochondrial movement. In contrast, retention of mitochondria in the bud was compromised in YPT11 and MYO2 mutants. Retention of mitochondria in the bud tip of wild-type cells results in a 60% decrease in mitochondrial movement in buds compared with mother cells. In ypt11Δ mutants, however, the level of mitochondrial motility in buds was similar to that observed in mother cells. Moreover, the myo2-66 mutant, which carries a temperature-sensitive mutation in the Myo2p motor domain, exhibited a 55% decrease in accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip, and an increase in accumulation of mitochondria at the retention site in the mother cell after shift to restrictive temperatures. Finally, destabilization of actin cables and the resulting delocalization of Myo2p from the bud tip had no significant effect on the accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip.

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria are essential organelles that are produced only from preexisting mitochondria, making the transfer of mitochondria into developing daughter cells necessary for daughter cell survival and cell proliferation. In budding yeast, mitochondrial inheritance occurs by cell cycle-linked mitochondrial mobilization and immobilization events (Simon et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1999). At G1 phase, after the selection of a bud site, mitochondria align along the mother-bud axis. During S, G2, and M phases, mitochondria display two types of behavior: some mitochondria undergo linear and polarized movement from mother to daughter cells, whereas other mitochondria become immobilized in the bud tip or in the tip of the mother cell distal to the site of bud emergence. Linear, bud-directed mitochondrial movement serves the essential function of transferring the organelle to the daughter cell. Immobilization of newly inherited mitochondria in the bud tip increases the efficiency of mitochondrial inheritance by retaining mitochondria in the bud, whereas equal distribution of the organelle between cells is achieved by immobilization of mitochondria in the tip of the mother cell distal to the bud (Yang et al., 1999). Finally, during mitosis, mitochondria are released from retention zones in the mother cell and bud and are redistributed in the dividing cells.

Linear, bud-directed mitochondrial movement in budding yeast depends on actin tracks. This interpretation is based on findings that 1) the pattern of mitochondrial movement resembles that of known track-dependent processes; 2) mitochondria colocalize with actin cables, bundles of actin filaments that align along the mother-bud axis; and 3) mitochondria require actin cables for movement from mother cells to developing daughter cells during cell division (Simon et al., 1995, 1997). Although mitochondrial movement seems to be track dependent and myosins are well-established as force generators for movement along actin tracks, deletion of the yeast myosin genes does not affect the velocity of mitochondrial movement (Simon et al., 1995). Therefore, early evidence indicated that mitochondria do not use myosin motors for their movement.

Instead, our studies support a role for the Arp2/3 complex as the force generator for movement of yeast mitochondria. The Arp2/3 complex is a conserved complex that stimulates actin polymerization-producing forces for extension of the leading edge of motile cells, movement of endosomes, and movement of pathogens (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes and Shigella flexneri) through the cytoplasm of infected host cells (reviewed in Goldberg, 2001). The interpretation that Arp2/3 complex and actin polymerization generate the forces necessary for mitochondrial movement is based on findings that 1) mitochondrial movement requires actin assembly and disassembly; 2) subunits of the Arp2/3 complex colocalize with mitochondria and are recovered with mitochondria during subcellular fractionation; 3) Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin polymerization occurs on mitochondria in intact yeast cells; and 4) mutations in Arp2/3 complex subunits inhibit mitochondrial movement, yet have no obvious effect on colocalization of mitochondria with actin cables (Boldogh et al., 2001).

Recent studies support a role for a type V myosin and a small Rab-like GTPase in mitochondrial inheritance in budding yeast (Itoh et al., 2002). Myo2p, one of the two type V myosins of yeast, is essential, accumulates in the bud tip, and is required for bud-directed transport of secretory vesicles, vacuoles, peroxisomes, late Golgi elements, and astral microtubules from the emanating spindle apparatus (Strobel et al., 1990; Johnston et al., 1991; Govindan et al., 1995; Beach et al., 2000; Catlett et al., 2000; Reck-Peterson et al., 2000; Yin et al., 2000; Hoepfner et al., 2001; Rossanese et al., 2001; Schott et al., 2002). Itoh et al. (2002) showed that the Rab-like protein Ypt11p has the capacity to bind to the Myo2p tail and interacts genetically with MYO2. Moreover, they found that deletion of YPT11 resulted in a delay in the localization of mitochondria in the bud during early stages of bud emergence, whereas overexpression of YPT11 resulted in an abnormal accumulation of mitochondria in the bud. These observations raised the possibility that Myo2p and Ypt11p may mediate mitochondrial movement during inheritance in budding yeast.

To further characterize the role of Ypt11p and Myo2p in mitochondrial inheritance, we studied the effect of mutations of YPT11 and MYO2 on mitochondrial movement, retention, and inheritance. Direct in vivo observations and measurements of mitochondrial dynamics demonstrate that mutation of either YPT11, MYO2, or MYO4 (the other type V myosin of yeast) has no effect on the velocity or track dependence of mitochondrial movement in the mother cell. Instead, our studies support a role for Ypt11p and Myo2p in the retention of newly inherited mitochondria in the bud. These observations reconcile the findings from Itoh et al. (2002) with existing models of forces that drive movement of yeast mitochondria. In addition, they provide the first steps toward understanding the mechanism underlying the retention of newly inherited mitochondria in the bud that occurs during yeast cell division.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Strains and Tagging of MYO2 Gene

Table 1 lists yeast strains used for this study. Yeast cell growth and manipulation were carried out according to established methods (Sherman, 2002).

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| BY4741 | MATa, his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Research Genetics |

| RG1140 | MATa, his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 ypt11Δ:: kanMX4 | Research Genetics |

| CRY1 | MATa ade2-loc can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | Stevens and Davis, 1998 |

| RSY21 | MATa ade2-loc can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 myo2-Δ61Q | Stevens and Davis, 1998 |

| 22AB | MATa/MATα, lys2-80(am)/lys2-80(am) ura3-52/ura3-52 his3Δ200/his3Δ200 trp1-1(am)/trp1-1(am) leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 | S. Brown (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) |

| MYO4ΔU5 | MATa/MATα lys2-80(am)/lys2-80(am) ura3-52/ura3-52 his3Δ200/his3Δ200 trp1-1(am)/trp1-1(am) leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 myo4:: URA3/myo4:: URA3 | S. Brown |

| VSY21 | MATα leu2-3,112 ura3-52 myo2-66 myo4Δ:: URA3 | This laboratory |

| MYY291 | MATα ura3 leu2 his3 | M. Yaffe (University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA) |

| MYY504 | MATα ura3 leu2 his3 mdm10Δ:: URA3 | M. Yaffe |

| MYY624 | MATα, leu2, his3, ura3, mdm12Δ:: URA3 | M. Yaffe |

| YPH252 | MATα leu2-3,112 his3-11 ade2-loc can1-100 trp1-1 lys2Δ ura3-11 | R. Jensen (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) |

| YPH253 | MATα mmm1-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11 ade2-loc can1-100 trp1-1 lys2Δ ura3-11 | R. Jensen |

| IBY153 | MATa/MATα tpm1-2:: LEU2/tmp1-2:: LEU2 tpm2Δ:: HIS3/tpm2Δ:: HIS3 his3Δ-200/his3Δ-200 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 lys2-80/lys2-801 trp1-1 ura3-52/trp1-1 ura3-52 MYO2/MYO2-GFP:TRP1 [pOLIl:HcRed:URA3] | This work |

| IBY152 | MATa/MAT tpm2Δ:: HIS3/tpm2Δ:: HIS3 his3Δ-200/his3Δ-200 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 lys2-80/lys2-801 trp1-1 ura3-52/trp1-1 ura3-52 MYO2/MYO2-GFP:TRP1 [pOLIl:HcRed:URA3] | This work |

The COOH terminus of Myo2p was tagged with a copy of the green fluorescent protein GFP(S65T), by using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based insertion into the chromosomal copy of the MYO2 gene (Longtine et al., 1998) in ABY973 And ABY971 cells (Pruyne et al., 1998). PCR fragments were first amplified from pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-TRP1 plasmid with the forward primer 5′AGTTGACCTTGTTGCCCAACAAGTCGTTCAAGACGGCCACggagcaggagcaggaCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA-3′, and the reverse primer 5′TTAGCATTCATGTACAATTTTGTTTCTCGCGCCATCAGTTGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC-3′ (underlined sequences correspond to the plasmid sequence, lowercase letters correspond to a GAGAG linker sequence that was introduced between the COOH terminus of Myo2p and NH2-terminal green fluorescent protein [GFP]). Yeast cells were transformed with the PCR product by the lithium acetate method (Gietz et al., 1995). Transformants that were positive for integration were validated by PCR, analyzed for protein expression by using Western blots, and analyzed for expression of fluorescently tagged protein by using fluorescence microscopy (see below). Addition of the GFP tag to Myo2p had no obvious effect on cellular growth, viability, polarity, or actin cytoskeleton organization. Moreover, the localization of Myo2p-GFP was similar to that of untagged Myo2p.

Visualization of Mitochondria and the Actin Cytoskeleton

Mitochondria were visualized in living cells by using a fusion protein consisting of the mitochondrial signal sequence of citrate synthase 1 fused to GFP (CS1-GFP). CS1-GFP was expressed using a centromere-based plasmid under control of the endogenous citrate synthase promoter (Okamoto et al., 2001). In some cases, mitochondria were visualized using a fusion protein consisting of the red-emitting fluorescent protein HcRed fused to the signal sequence of subunit 9 of F0-ATP synthase (OLI1-HcRed). To create this construct, HcRed sequence was amplified by PCR by using the pHcRed1 vector (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) as a template. The forward and reverse primers used for this amplification were 5′GGTCGCCGGATCCATGGTGAGCGGCCTGCTGAAGG3′ and 5′AGTCGCGCTCGAGTCAGTTGGCCTTCTCGGG3′, respectively. The resulting PCR product was cloned into a pRS426-based, high copy-number vector (gift from J. Shaw, University of Utah) directly after a mitochondrial presequence of subunit 9 of the F0-ATP synthase at BamH1 and XhoI sites. OLI1-HcRed was expressed constitutively from an ADH promoter.

Yeast cells were transformed with plasmids bearing CS1-GFP or OLI1-HcRed by using the lithium acetate method (see above). When expressed in living yeast cells, both CS1-GFP and OLI1-HcRed produced a robust signal that localized exclusively to mitochondria and had no detectable effect on mitochondrial morphology or respiration under our experimental conditions. For most experiments, cells expressing CS1-GFP or OLI1-HcRed were grown to mid-log phase in synthetic, glucose-based liquid media at 30°C. Temperature-sensitive mutants were grown at 23°C.

For some experiments, mitochondria were visualized in living cells by using the membrane potential-sensing dye 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The cell density of mid-log phase samples was adjusted to 1 × 107 cells/ml, and the sample was incubated in medium containing 20 ng/ml DiOC6 for 5 min at room temperature (RT). Cells were washed once and resuspended to a final concentration of 2 × 108 cells/ml in medium. Samples were mounted on microscope slides and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. At the concentrations used, DiOC6 is specific for mitochondria and has no detectable effect on cell viability (Simon et al., 1995).

The actin cytoskeleton was visualized using rhodamine-phalloidin (Molecular Probes), a ligand that binds specifically to actin polymers (Cooper, 1987). Rhodamine-phalloidin was added to fixed samples to a final concentration of 2.5 mM in a solution consisting of a 4:1 ratio of NS (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ZnCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.05% [vol/vol] 2-mercaptoethanol) to methanol, and samples stood in the dark for 10 min at RT. Stained cells were mounted on microscope slides and visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Light Microscopy

Images were collected with an Axioskop 2 Plus microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) by using a Plan-Apochromat 100×, 1.4 numerical aperture objective lens, and a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Orca-100; Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). Illumination with a 100-W mercury arc lamp was controlled with a shutter (Uniblitz D122; Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY). Camera control and image enhancement were performed using Open-Lab software (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom).

For analysis of mitochondrial morphology, 25 z-sections were obtained at 0.2-μm intervals through the entire cell. z-Sectioning for three-dimensional (3D) imaging was carried out using a piezoelectric focus motor mounted on the objective lens of the microscope (Polytech PI, Auburn, MA). Out-of-focus light was removed by deconvolution, and each series of deconvolved images was projected and rendered with Volocity software (Improvision).

Quantitation of Mitochondrial Movement In Vivo

Mitochondria were defined as motile if they displayed linear movement for three consecutive still frames. Only the tip of the organelle was evaluated for movement. For any given cell, mitochondrial movement was evaluated only in a single optical plane. The velocities of motile mitochondria were determined by measuring the change in position of the tip of each moving mitochondrion as a function of time in time-lapse series recorded at 1-s intervals >1 min of real time. Only velocities of organelles undergoing linear movement for at least three consecutive frames were measured. For all velocity measurements, ImageJ (public domain, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) was used to determine the change in position (x-y coordinates) of mitochondria per unit time, and these were averaged to obtain a mean velocity for all mitochondria in a strain.

RESULTS

Deletion of YPT11 Results in Defects in Mitochondrial Inheritance without Affecting Mitochondrial Morphology, Motility, or Association with Actin Cables

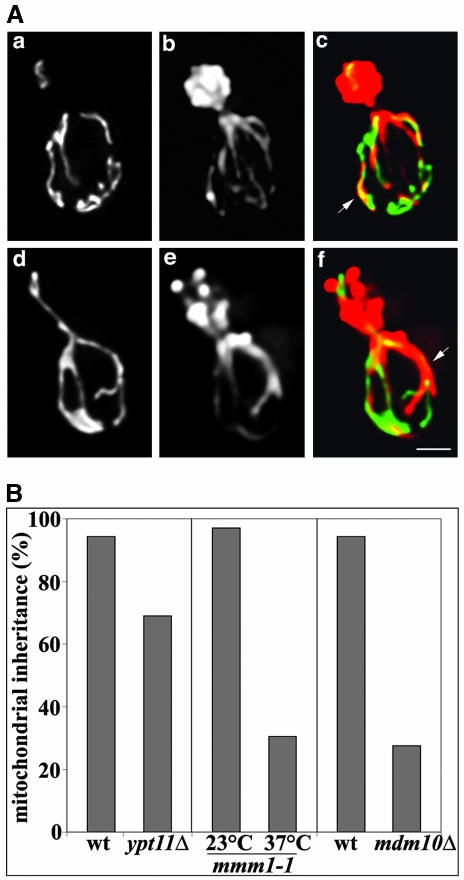

In wild-type cells, mitochondria are long, tubular structures that colocalize with actin cables, bundles of actin filaments that align along the mother-bud axis. We found that mitochondrial morphology and colocalization with actin cables were similar in wild-type cells and ypt11Δ mutants (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Deletion of YPT11 impairs mitochondrial inheritance without affecting mitochondrial morphology or interactions of mitochondria with actin cables. (A) YPT11 wild-type cells (BY4741) (a-c) and deletion mutants (RG1140) (d-f) expressing mitochondria-targeted GFP (CS1-GFP) were grown to mid-log phase. Cells were fixed and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin. z-Sections of cells were collected, deconvolved, and projected to a single image. GFP-labeled mitochondria (a and d), actin organization (b and e), as well as an overlay of mitochondria in green and actin in red (c and f) are shown. Arrows point to examples of colocalization of mitochondria with actin cables. Bar, 1 μm. (B) YPT11 wild-type cells (BY4741) and deletion mutants (RG1140), and MDM10 wild-type cells (MYY291) and deletion mutants (MYY504) were grown to mid-log phase. Temperature-sensitive mmm1-1 mutant (YPH253) cells were grown to mid-log phase at 23°C and then shifted to 37°C for 3 h and 45 min. Mitochondria were visualized in YPT11 wild type and deletion strains by using CS1-GFP. In all other strains mitochondria were visualized using the membrane potential-sensing dye DiOC6. Mitochondrial inheritance was determined by scoring the percentage of yeast bearing small buds that contained mitochondria within the bud.

Because mitochondria enter the bud almost as soon as it emerges, >90% of small buds in wild-type cells contain mitochondria. We analyzed the effect of deletion of YPT11 on the localization of mitochondria in small buds. In confirmation of previous studies (Itoh et al., 2002), we found that deletion of YPT11 resulted in a 23% inhibition of mitochondrial inheritance during this early stage in the yeast cell division cycle (Figure 1B). For comparison, we also evaluated mitochondrial inheritance in yeast bearing mutations in the “mitochore,” a mitochondrial membrane protein complex that links mitochondrial membranes and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) to the actin cytoskeleton for movement and inheritance (Boldogh et al., 2003). The mitochore mutants used carried a deletion in MDM10 (mdm10Δ) or a temperature-sensitive mutation in MMM1 (mmm1-1). mdm10Δ cells and mmm1-1 mutants incubated at restrictive temperatures showed a 70% inhibition of mitochondrial inheritance in small buds. Thus, the defect in mitochondrial inheritance observed in ypt11Δ cells was less severe than that observed in yeast bearing mutations in known mitochondrial inheritance mediators.

Because previous studies on Ypt11p examined mitochondrial distribution in fixed cells, it was not possible to draw conclusions regarding the role of Ypt11p in mitochondrial motility. To address this issue, we used time-lapse fluorescence microscopy to visualize movement of GFP-labeled mitochondria in dividing yeast cells. In wild-type yeast, mitochondria display linear, bud-directed movement with an average velocity of 0.185 μm/s. We found that the velocity of mitochondrial movement in ypt11Δ cells, 0.172 μm/s, did not differ significantly from that observed in wild-type cells. Thus, the defects in mitochondrial inheritance observed in the ypt11Δ cells were not due to defects in mitochondrial morphology, the association of mitochondria with actin cables, or mitochondrial movement.

Mutations of the Two Type V Myosins of Yeast Have No Effect on Mitochondrial Morphology, Association of Mitochondria with Actin Cables, or the Velocity of Movement of Mitochondria from Mother Cells to Buds

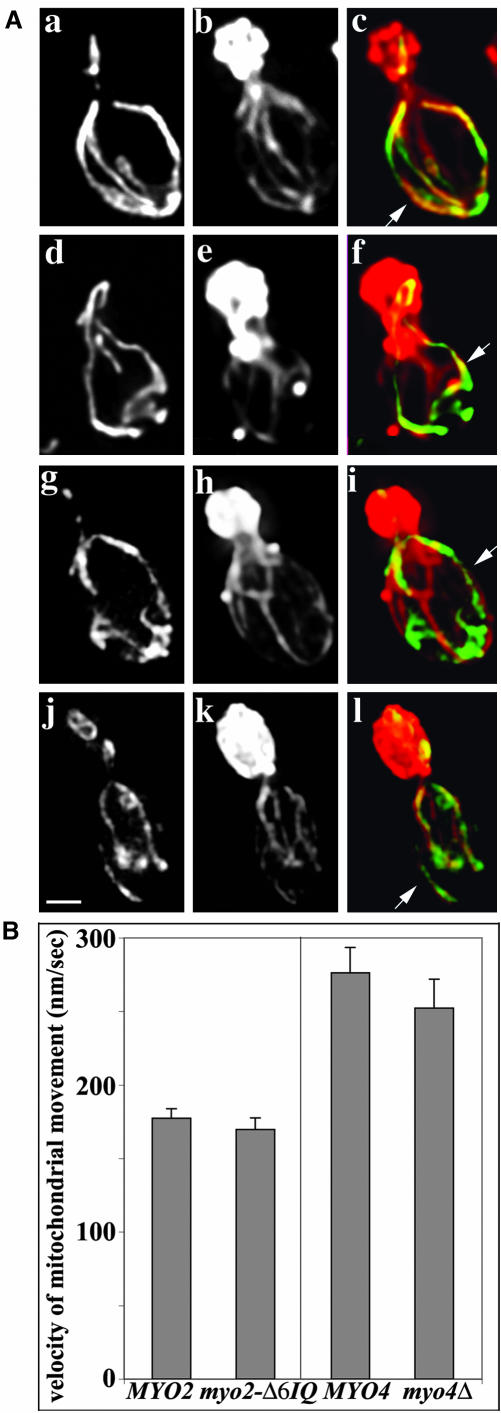

Previously, we showed that mitochondria move with normal velocities in the myo2-66 mutant, a cell that carries a temperature-sensitive mutation in the Myo2p motor domain, and in yeast carrying a deletion in MYO4 (Simon at al., 1995). Here, we took a different approach to study the role of type V myosin in mitochondrial morphology and movement in budding yeast. First, all imaging studies were carried out with greater spatial resolution by using digital deconvolution and 3D reconstruction, and a 15- to 20-fold increase in temporal resolution. Second, we used different mutants to study Myo2p motor activity. The step size of myosin V depends on the lever arm, an α-helical domain containing six IQ motifs (Vale, 2003). Schott et al. (1999) recently showed that deletion of the IQ repeats in the Myo2p lever arm (myo2-Δ6IQ) had no obvious effect on cell viability or polarity. However, expression of myo2-Δ6IQ at wild-type levels in lieu of endogenous Myo2p resulted in a >5-fold decrease in the velocity of vesicle movement.

If mitochondrial movement is driven by Myo2p, then reduction of the length of the Myo2p lever arm should reduce the velocity of mitochondrial movement. To test this hypothesis, we examined mitochondrial motility in a Myo2p mutant that contains no IQ repeats in its lever arm (myo2- Δ6IQ). We found that shortening of the Myo2p lever arm had no significant effect on mitochondrial morphology or association with actin cables (Figure 2A). In addition, shortening of the Myo2p lever arm had no effect on the velocity of mitochondrial movement in the mother cell or in the bud (Figure 2B). Similarly, we found that deletion of the other myosin V gene in yeast, MYO4, had no effect on mitochondrial morphology, colocalization of mitochondria with actin cables, or the velocity of mitochondrial movement (Figure 2). These findings argue against the idea that the type V myosins of yeast, Myo2p, and Myo4p are the motors for mitochondrial movement from mother cells to buds in budding yeast.

Figure 2.

Mutation of either of the type V myosins of yeast has no effect on mitochondrial morphology, association of mitochondria with actin cables, or the rate of movement of mitochondria from mother cells to buds. (A) Wild-type MYO2 (CRY1) (a-c), myo2-Δ6IQ (RSY21) cells (d-f), wild-type MYO4 (22AB) cells (g-i), and myo4Δ (MYO4ΔU5) mutants (j-l) expressing CS1-GFP were grown to midlog phase at 30°C. Cells were fixed and stained with rhodaminephalloidin. z-Sections of cells were collected, deconvolved, and projected to a single image. GFP-labeled mitochondria (a, d, g, and j), actin organization (b, e, h, and k), and the overlay of mitochondria in green and actin in red (c, f, i, and l) are shown. Arrows point to examples of colocalization of mitochondria with actin cables. Bar, 1 μm. (B) Velocities of mitochondrial movement in MYO2 wild-type cells, myo2-Δ6IQ mutant cells, MYO4 wild-type and myo4Δ cells expressing CS1-GFP were measured by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy as described under Materials and Methods.

Mutation of YPT11 Results in Defects in Retention of Mitochondria in the Bud Tip

Here, we studied the possible role of Ypt11p in the retention of newly inherited mitochondria in developing daughter cells. During this process, mitochondria undergo linear, directed movement into the bud tip. Immobilization of these newly inherited organelles in the bud tip results in an accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip and a significant decrease in the extent of mitochondrial movement in the bud.

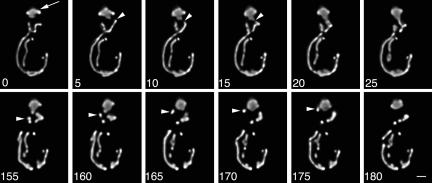

Four-dimensional (4D) optical imaging (time-lapse imaging combined with 3D reconstruction) of GFP-labeled mitochondria in wild-type cells revealed the motility events associated with retention of newly inherited mitochondria in the bud (Figure 3). Mitochondria located in the bud adjacent to the bud neck displayed movements similar to those observed in the mother cell. That is, they underwent linear, bud tip-directed movement. In contrast, at the bud tip, mitochondria accumulate and displayed only random movements. These observations indicate that retention of mitochondria in the bud occurs by anchorage and immobilization of the organelle in the bud tip.

Figure 3.

Events associated with the retention of mitochondria in the bud. Wild-type yeast expressing CS1-GFP (BY4741) were grown to mid-log phase and monitored by 4D imaging (time-lapse microscopy combined with 3D reconstruction). z-Sections through the entire cell were obtained as described above. The interval between each Z-series was 5 s. The still frames shown are two-dimensional projections of deconvolved 3D reconstructions obtained at 0-25 s (top) and 155-180 s (bottom) from a single 4D time-lapse series. Arrow points to mitochondria that are immobilized and accumulated in the tip of the bud. Arrowheads in the top and bottom panels point to mitochondria that undergo linear movement toward the bud tip. Bar, 1 μm. Please refer to Supplemental Information to view a movie of this 4D time-lapse series.

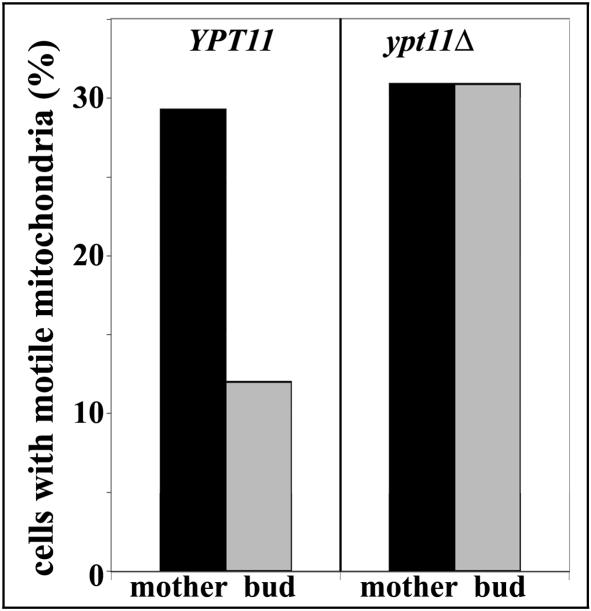

Quantitation of mitochondrial motility revealed that ∼30% of mother cells displayed mitochondrial movement in a single optical plane within the 1-min imaging period. There was 60% less mitochondrial movement in the bud compared with the mother cell (Figure 4). Thus, the majority of newly inherited mitochondria seem to be retained in the bud tip.

Figure 4.

Deletion of YPT11 results in defects in immobilization of newly inherited mitochondria in the bud. YPT11 wild-type cells (BY4741) and deletion mutants (RG1140) expressing mitochondria-targeted GFP (CS1-GFP) were grown to mid-log phase. Time-lapse fluorescence imaging was used to monitor movements of CS1-GFP-labeled mitochondria. Images were acquired at 1 s intervals over a period of 1 min. The percentage of cells displaying mitochondrial movement in mother cells and buds in wild-type and ypt11Δ cells was determined as described under Materials and Methods.

Ypt11p and Myo2p Are Required for Retention of Mitochondria in the Bud Tip

To evaluate the role of Ypt11p in retention of mitochondria in the bud, we studied the effect of deletion of YPT11 on the immobilization of mitochondria in the bud. Because mitochondrial inheritance is delayed in ypt11Δ cells, we carried out this motility analysis in medium-budded cells. At this stage in the cell cycle, ypt11Δ cells do not show any defect in mitochondrial inheritance. However, deletion of YPT11 resulted in defects in the immobilization of mitochondria in the bud tip. Indeed, the level of mitochondrial movement in the bud of ypt11Δ cells was similar to that observed in the mother cells (Figure 4).

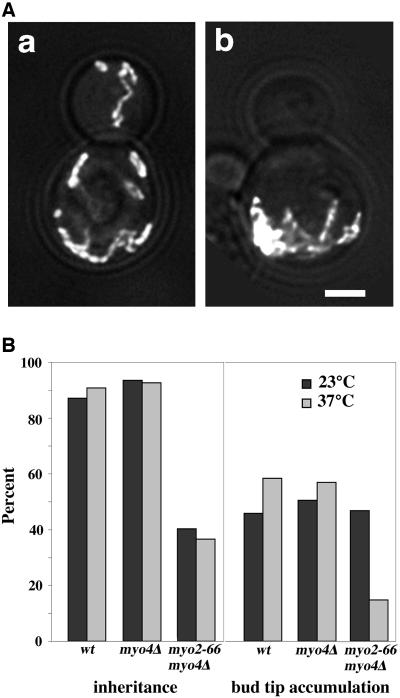

We used myo2-66 mutants, yeast that carry a single amino acid substitution in the Myo2p motor domain that results in loss of motor function after incubation at 37°C for 45 min, to study a role of Myo2p in retention of mitochondria in the bud (Lillie and Brown, 1994). For comparison, we examined mitochondrial retention in the bud of wild-type cells and myo4Δ mutants. Although mitochondria were tubular in the myo2-66 mutant incubated at restrictive temperature, they were aggregated and failed to align along the mother-bud axis (Figure 5). Interestingly, we found that aggregated mitochondria in the myo2-66 mutant were concentrated at the tip of the mother cell distal to the site of bud emergence, the site where some mitochondria are normally immobilized and retained in the mother cell.

Figure 5.

Mutation of the Myo2p motor domain results in defects in mitochondrial inheritance, aggregation of mitochondria in the distal tip of the mother cell, and defects in accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip. (A) Yeast bearing mutations in both type V myosins (myo2-66 and myo4Δ; VSY21) were transformed with pCS1-GFP. The strain was grown to mid-log phase at 23°C and incubated at 23°C (a) or 37°C, the restrictive temperature for myo2-66, (b) for 45 min before fixation. z-Sections of GFP-labeled mitochondria were collected, deconvolved, and projected to a single image as described under Materials and Methods. Phase images of the same cells were overlaid on the fluorescence images. Bar, 1 μm. (B) Mid-log phase myo2-66/myo4Δ mutants (VSY21), myo4Δ mutants (MYO4ΔU5) or wild-type strains (22AB) from the same genetic background that expressed CS1-GFP, were incubated at 23 or 37°C and fixed as for A. Mitochondrial inheritance (left) was assayed as for Figure 1B. Accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip of each cell type (right) was determined by scoring the percentage of cells that displayed a buildup of mitochondria in the tip of the bud. All cells that were analyzed for bud tip accumulation of mitochondria contained mitochondria in their bud tips.

Because mitochondria are aggregated in myo2-66 mutants, it is difficult to evaluate the extent of mitochondrial movement in these cells. Therefore, we monitored mitochondrial retention in myo2-66 and myo4Δ mutants by analysis of accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip. To ensure that any retention defects observed were not due to failure to transfer mitochondria into the bud, we restricted our analysis to cells that contained mitochondria in the bud. Mitochondrial inheritance was compromised in the myo2-66 mutant, consistent with the reported role of Myo2p in mitochondrial inheritance (Itoh et al., 2002). In the myo2-66 mutant where mitochondria were present in the bud tip, we observed that mitochondria accumulated in the bud tip in 65% of myo2-66 cells incubated at permissive temperature. In contrast, only 18% of myo2-66 mutants incubated at 37°C showed accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip (Figure 5). Moreover, deletion of MYO4 had no obvious effect on accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip (Figure 5). Thus, loss of Myo2p motor function results in defects in retention of mitochondria in the bud tip, and increased accumulation of mitochondria in the retention site in the mother cell.

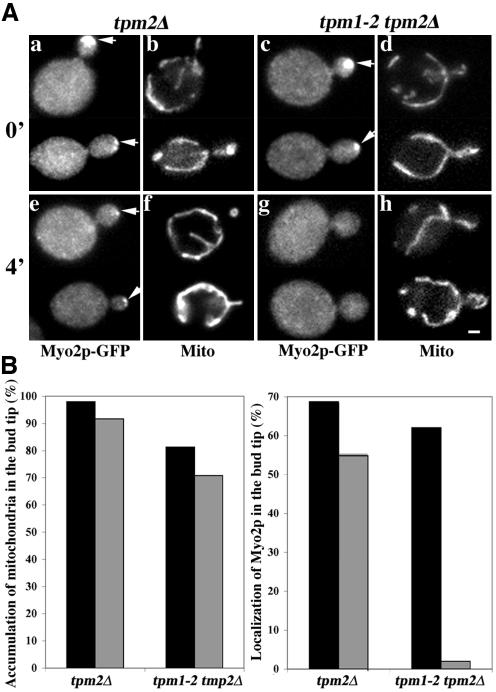

Myo2p localizes to the bud tip, the site where mitochondria are immobilized and retained. Therefore, we studied whether localization of Myo2p to the bud tip is required for retention of mitochondria at that site. Previous studies indicate that tropomyosin-containing actin cables contribute to localization of Myo2p at the bud tip (Pruyne et al., 1998). That is, incubation of yeast bearing a temperature-sensitive mutation in the tropomyosin gene, TPM1, and a deletion in the TPM2 gene (tpm1-2 tpm2Δ) at restrictive temperature results in rapid loss of actin cables and depolarization of Myo2p. We observe some delocalized Myo2p after short-term incubation of the tpm2Δ strain at 35°C, and loss of all detectable Myo2p in the bud tip after incubation of the tpm1-2 tpm2Δ strain at 35°C (Figure 6). Under these conditions where Myo2p is either partially or entirely delocalized, we do not detect any significant effect on accumulation of mitochondria at the bud tip. Thus, localization of Myo2p at the bud tip is not required for retention of mitochondria at that site.

Figure 6.

Mislocalization of Myo2p has no effect on retention of mitochondria in the bud tip. (A) Yeast carrying a deletion in the tropomyosin gene TPM2 (tpm2Δ) and either wild-type tropomyosin gene (TPM1; IBY152) (a and b, e and f) or temperature-sensitive TPM1 mutation (tpm1-2; IBY153) (c and d, g and h) were grown to mid-log phase at permissive temperatures (23°C). Each of these strains expressed Myo2p tagged at its C terminus with GFP (Myo2p-GFP) and mitochondria-targeted HcRed (OLI1-HcRed). Aliquots from this culture were incubated at temperatures restrictive for the tpm1-2 allele (35°C) for 0 min (a-d) or 4 min (e-h). The cells were fixed and OLI1-HcRed-labeled mitochondria (b, d, f, and h) and Myo2p-GFP (a, c, e, and g) were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Arrows point to instances of accumulation of Myo2p in the bud tip. Bar, 1 μm. (B) Aliquots from TPM1 tpm2Δ and tpm1-2 tpm2Δ cells were incubated at temperatures restrictive for the tpm1-2 allele (35°C) for 0 min (black bars) or 4 min (gray bars) and the cells were fixed (see above). OLI1-HcRed-labeled mitochondria (left) and Myo2p-GFP (right) were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip was assessed as for Figure 5. Myo2p-GFP was scored as depolarized if it did not accumulate in the bud tip. Mislocalization of Myo2p had no effect on accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip.

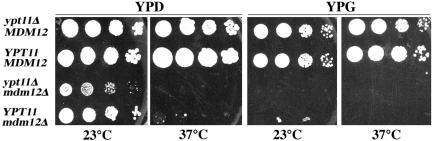

Synthetic Effects in Yeast Carrying Mutations in YPT11 and MDM12

Our studies indicate that two distinct pathways contribute to the segregation of mitochondria in mitotic yeast cells: movement of mitochondria from mother to daughter cells and retention of newly inherited mitochondria in daughter cells. If this is the case, then mutations that affect both pathways should produce defects that are more severe compared with mutations in either pathway. To test this hypothesis, diploid yeast cells bearing deletions in YPT11 and in the mitochore subunit, Mdm12p, were sporulated and the growth rates of the resulting haploid progeny were monitored.

As described above, deletion of mitochore subunits produces defects in mitochondrial motility and defects in inheritance of mitochondria and mtDNA. As a result, mitochore mutants exhibit slow growth on glucose-based media and no growth on media containing a nonfermentable carbon source. In contrast, deletion of YPT11 has no measurable effect on growth rates on media containing fermentable or nonfermentable carbon sources. We find that cells carrying both deletions are viable, but display slower growth on glucose compared with ypt11Δ or mdm12Δ single mutants (Figure 7). The results shown are representative of analyses of five tetrads. In one case, an mdm12Δ cell grew at the same rate as a ypt11Δ/mdm12Δ double mutant. However, growth of that particular mdm12Δ mutant was severely compromised. Overall, our genetic evidence supports the model that Ypt11p and mitochore subunits contribute to different pathways that both affect mitochondrial inheritance.

Figure 7.

Synthetic growth defect of ypt11Δ with mdm12Δ. ypt11Δ/YPT11 mdm12Δ/MDM12 heterozygous diploid cells derived from mating the haploid strains, RG1140 (ypt11Δ) and MYY624 (mdm12Δ), were sporulated, and the tetrads were dissected. Growth characteristics of the haploid spores were tested on glucose-based solid media (YPD) and glycerol-based solid media (YPG). The panel shows a dilution series of a representative set of tetrads after 4 d of incubation at 23 and 37°C.

DISCUSSION

Many proteins are enriched in the bud tip, including the components of the secretion machinery (e.g., the exocyst), bud site selection proteins, and signal transduction proteins required for cytoskeletal organization and/or establishment of cell polarity (Snyder, 1989; Brockerhoff and Davis, 1992; Yamochi et al., 1994; Lillie and Brown, 1994; Amberg et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1997; Guo et al., 2001; Harkins et al., 2001; Ozaki-Kuroda et al., 2001). Indeed, organelles including the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria are immobilized in the bud tip (Fehrenbacher et al., 2002). However, the mechanism underlying targeting and retention of proteins and organelles in the bud tip is not well understood. Our studies reveal the first set of proteins that are required for retention of mitochondria in the bud tip.

We found that the type V myosins Myo2p and Myo4p and Ypt11p, a Rab-like protein that can bind to Myo2p, are not required for movement of mitochondria into the bud. This interpretation is based on findings that neither deletion of YPT11, shortening of the lever arm of Myo2p, nor deletion of MYO4 had any effect on 1) mitochondrial morphology, 2) actin organization, 3) colocalization of mitochondria with actin cables, or 4) the rate of mitochondrial movement from mother cells to developing buds. Instead, YPT11 and MYO2 mutants showed defects in other processes that affect mitochondrial inheritance.

Analysis of mitochondria in living yeast cells revealed 1) a 60% decrease in the amount of mitochondrial motility in wild-type buds compared with mother cells, 2) accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip, and 3) no significant retrograde movement of mitochondria from buds into the mother cell (Figures 1 and 3; Simon et al., 1995). These findings support the model that newly inherited mitochondria are retained in the bud by immobilization in the bud tip.

We found that the level of mitochondrial movement was equal in mother cells and buds in ypt11Δ mutants. Thus, deletion of YPT11 results in defects in immobilization and therefore hinders retention of mitochondria in the bud. Similarly, we found that a yeast strain carrying a temperature-sensitive mutation in MYO2 showed temperature-dependent defects in the accumulation of mitochondria in the bud tip. Together, these findings support a role for Ypt11p and Myo2p in the retention of mitochondria in the bud tip. Itoh et al. (2002) described delayed transmission of mitochondria into buds upon loss of function of Ypt11p or Myo2p and increased accumulation of mitochondria in the bud upon overexpression of Ypt11p. Each of these phenotypes is consistent with a role for Myo2p and Ypt11p in the retention of mitochondria in the bud tip. Thus, our findings reconcile results from Itoh et al. (2002) with existing models for mitochondrial inheritance in budding yeast and provide clues for the molecular mechanism underlying retention of newly inherited mitochondria in the bud.

Yet to be determined, however, is the mechanism of action of Myo2p and Ypt11p in the bud tip retention of mitochondria. Because Myo2p and Ypt11p accumulate in the bud tip, they may serve as capture device(s) for retention of mitochondria at that site. Alternatively, it is possible that Myo2p and Ypt11p drive movement of mitochondrial retention factor(s) from the mother cell to the bud tip. We favor the latter hypothesis for several reasons. First, the motor activity of Myo2p is required for retention of mitochondria in the bud tip and for transport of cargoes including secretory vesicles from mother cells to buds. Second, there is evidence for a role of Rab-like GTPases in vesicular movement. Specifically, Rab-like GTPases have been implicated as adapters for linking vacuoles and vesicles to the tail domain of type V myosins in yeast and other eukaryotes (Wu et al., 2002). Moreover, Ypt11p shows two-hybrid interactions with Rab activators that play a role in ER-to-Golgi transport (YIP4 and YIP5) and with proteins that localize to COP-II-coated vesicles (Uetz et al., 2000; Ito et al., 2001). Third, we find that displacement of Myo2p from the bud tip has no effect on the accumulation of mitochondria at the bud tip. Therefore, results from our laboratories and others support the model that Myo2p and Ypt11p mediate the movement of membrane-bound retention factors from mother cells to the plasma membrane of the bud tip. Indeed, because mitochondria accumulate in the site for retention of mitochondria in the mother cell when Myo2p motor activity is lost, it is possible that Myo2p and Ypt11p mediate movement of immobilization factors from the retention site in the distal tip of the mother cell to the retention site in the bud tip. Future studies will further elucidate the precise role that Myo2p and Ypt11p play in the retention of mitochondria during inheritance in budding yeast.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Pon laboratory for critical evaluation of the manuscript; Drs. A. Bretscher, M. Yaffe, and R. Jensen for yeast strains; Dr. J. Shaw for plasmids; Drs. M. Longtine and J. Pringle for tagging cassette DNA; and L. Pantalena and T. Huckaba for constructing HcRed-containing plasmid and providing primers for chromosomal tagging of MYO2. This work was supported by research grants to L.P. from the National Institutes of Health (GM-45735 and GM-66037).

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E04-01-0053. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-01-0053.

Abbreviations used: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA.

Online version of this article contains supporting material. Online version is available at www.molbiolcell.org.

References

- Amberg, D.C., Zahner, J.E., Mulholland, J.W., Pringle, J.R., and Botstein, D. (1997). Aip3p/Bud6p, a yeast actin-interacting protein that is involved in morphogenesis and the selection of bipolar budding sites. Mol. Biol. Cell. 8, 729-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach, D.L., Thibodeaux, J., Maddox, P., Yeh, E., and Bloom, K. (2000). The role of the proteins Kar9 and Myo2 in orienting the mitotic spindle of budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 10, 1497-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldogh, I.R., Nowakowski, D.W., Yang, H-C., Chung, H., Karmon, S., Royes, P., and Pon, L.A. (2003). A protein complex containing Mdm10p, Mdm12p and Mmm1p links mitochondrial membranes and DNA to the cytoskeleton-based segregation machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14, 4618-4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldogh, I.R., Yang, H.-C., Nowakowski, W.D., Karmon, S.L., Hays, L.G., Yates, J.R., III, and Pon, L.A. (2001). Arp2/3 complex and actin dynamics are required for actin-based mitochondrial motility in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3162-3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockerhoff, S.E., and Davis, T.N. (1992). Calmodulin concentrates at regions of cell growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 118, 619-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlett, N.L., Deux, J.E., Tang, F., and Weisman, L.S. (2000). Two distinct regions in a yeast myosin-V tail domain are required for the movement of different cargoes. J. Cell Biol. 150, 513-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.C., Kim, Y.J., and Chan, C.S. (1997). The Cdc42 GTPase-associated proteins Gic1 and Gic2 are required for polarized cell growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 11, 2958-2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J.A. (1987). Effects of cytochalasin and phalloidin on actin. J. Cell Biol. 105, 1473-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacher, K.L., Davis, D., Boldogh, I., Wu, M., and Pon, L.A.,. (2002). ER dynamics, inheritance and cytoskeletal interactions in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13, 854-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz, R.D., Schiestl, R.H., Willems, A.R., and Woods, R.A. (1995). Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast 11, 355-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, M.B. (2001). Actin-based motility of intracellular microbial pathogens. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 595-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, B., Bowser, R., and Novick, P. (1995). The role of Myo2, a yeast class V myosin, in vesicular transport. J. Cell Biol. 128, 1055-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W., Tamanoi, F., and Novick, P. (2001). Spatial regulation of the exocyst complex by Rho1 GTPase. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 353-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkins, H.A., Page, N., Schenkman, L.R., De Virgilio, C., Shaw, S., Bussey, H., and Pringle, J.R. (2001). Bud8p and Bud9p, proteins that may mark the sites for bipolar budding in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12, 2497-2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoepfner, D., van den Berg, M., Philippsen, P., Tabak, H.F., and Hettema, E.H. (2001). A role for Vps1p, actin, and the Myo2p motor in peroxisome abundance and inheritance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 155, 979-990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T., Chiba, T., Ozawa, R., Yoshida, M., Hattori, M., and Sakaki, Y. (2001). A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 4569-4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, T., Watabe, A., Toh-E.A., and Matsui, Y. (2002). Complex formation with Ypt11p, a rab-type small GTPase, is essential to facilitate the function of Myo2p, a class V myosin, in mitochondrial distribution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7744-7757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, G.C., Prendergast, J.A., and Singer, R.A. (1991). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MYO2 gene encodes an essential myosin for vectorial transport of vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 113, 539-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie, S.H., and Brown, S.S. (1994). Immunofluorescence localization of the unconventional myosin, Myo2p, and the putative kinesin-related protein, Smy1p, to the same regions of polarized growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 125, 825-842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M.S., McKenzie, A., III, Demarini, D.J., Shah, N.G., Wach, A., Brachat, A., Philippsen, P., and Pringle, J.R. (1998). Additional modules for versatile and economical P.C.R-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, K., Perlman, P.S., and Butow, R.A. (2001). Targeting of green fluorescent protein to mitochondria. Methods Cell Biol. 65, 277-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki-Kuroda, K., Yamamoto, Y., Nohara, H., Kinoshita, M., Fujiwara, T., Irie, K., and Takai, Y. (2001). Dynamic localization and function of Bni1p at the sites of directed growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 827-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne, D.W., Schott, D.H., and Bretscher, A. (1998). Tropomyosin-containing actin cables direct the Myo2p-dependent polarized delivery of secretory vesicles in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1931-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck-Peterson, S.L., Provance, D.W., Jr., Mooseker, M.S., and Mercer, J.A. (2000). Class V myosins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1496, 36-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossanese, O.W., Reinke, C.A., Bevis, B.J., Hammond, A.T., Sears, I.B., O'Connor, J., and Glick, B.S. (2001). A role for actin, Cdc1p, and Myo2p in the inheritance of late Golgi elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 153, 47-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott, D., Ho, J., Pruyne, D., and Bretscher, A. (1999). The COOH-terminal domain of Myo2p, a yeast myosin V, has a direct role in secretory vesicle targeting. J. Cell Biol. 147, 791-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott, D., Huffaker, T., and Bretscher, A. (2002). Microfilaments and microtubules: the news from yeast. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5, 564-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F. (2002). Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 350, 3-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, V.R., Karmon, S.L., and Pon, L.A. (1997). Mitochondrial inheritance: cell cycle and actin cable dependence of polarized mitochondrial movements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 37, 199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, V.R., Swayne, T.C., and Pon, L.A. (1995). Actin-dependent mitochondrial motility in mitotic yeast and cell-free systems: identification of a motor activity on the mitochondrial surface. J. Cell Biol. 130, 345-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, M. (1989). The SPA2 protein of yeast localizes to sites of cell growth. J. Cell Biol. 108, 1419-1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, R.C., and Davis, T.N. (1998). Mlc1p is a light chain for the unconventional myosin Myo2p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 142, 711-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, M.C., Seperack, P.K., Copeland, N.G., and Jenkins, N.A. (1990). Molecular analysis of two mouse dilute locus deletion mutations: spontaneous dilute lethal20J and radiation-induced dilute prenatal lethal Aa2 alleles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 501-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz, P., et al. (2000). A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403, 623-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale, R. (2003). Myosin V motor proteins: marching stepwise towards a mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 163, 445-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.S., Rao, K., Zhang, H., Wang, F., Sellers, J.R., Matesic, L.E., Copeland, N.G., Jenkins, N.A., and Hammer, J.A., III. (2002). Identification of an organelle receptor for myosin-Va. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamochi, W., Tanaka, K., Nonaka, H., Maeda, A., Musha, T., and Takai, Y. (1994). Growth site localization of Rho1 small GTP-binding protein and its involvement in bud formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 125, 1077-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.C., Palazzo, A., Swayne, T.C., and Pon, L.A. (1999). A retention mechanism for distribution of mitochondria during cell division in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 9, 1111-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H., Pruyne, D., Huffaker, T.C., and Bretscher, A. (2000). Myosin V orientates the mitotic spindle in yeast. Nature 406, 1013-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.