After downstaging of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in patients with initially unresectable HCC, long-term outcomes of salvage surgery as additional therapy were evaluated. Treatment method and response to TACE were independent prognostic factors for survival. Salvage surgery after downstaging of unresectable HCC had a survival benefit only for patients with macroscopic vascular invasion or a partial response to TACE.

Keywords: Transarterial chemoembolization, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Downstaging, Salvage surgery, Overall survival

Abstract

Introduction.

This study evaluated long-term outcomes of salvage surgery as additional therapy following downstaging of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in patients with initially unresectable HCC.

Methods.

A retrospective analysis was performed of 831 consecutive patients with unresectable HCC who underwent TACE as initial treatment between June 2004 and December 2014. Of these, 82 patients with downstaged resectable HCC were enrolled in this study: 43 received salvage surgery (S group) and the remaining 39, who refused salvage resection, were the control group (T group). The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS).

Results.

The median OS in the S and T groups was 49 and 31 months, respectively (p = .027). The 2-, 4-, and 5-year survival rates were 93%, 47%, and 26% in the S group and 74%, 18%, and 10% in the T group, respectively (p = .019). Treatment modality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.337; 95% confidential interval [CI], 0.184–0.616; p < .001) and response to TACE (complete vs. partial; HR, 3.154; 95% CI, 1.709–5.822; p < .001) were independent prognostic factors for survival. The median OS for patients in the complete response and partial response (PR) subgroups was 50 and 49 months, respectively, in the S group and 54 and 24 months, respectively, in the T group (p = .699 and p < .001, respectively). The median OS for HCC patients with macroscopic vascular invasion (MVI) was 58 and 30 months in the S and T groups, respectively (p = .024).

Conclusion.

Salvage surgery after downstaging of unresectable HCC had a survival benefit only for patients with MVI or a PR to TACE.

Implications for Practice:

The results of this study suggest that salvage liver resection after downstaging of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with a complete response to transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) has a comparable long-term outcome in this good-prognosis group. Salvage liver resection may provide a better long-term outcome compared with TACE alone, but only in patients with macroscopic vascular invasion or those with a partial response to TACE.

Abstract

摘要

引言. 本研究评价了挽救性手术作为最初不可手术的肝细胞癌 (HCC) 患者在经动脉化疗栓塞 (TACE) 治疗降期后的额外治疗的远期转归。

方法. 对2004年6月至2014年12月间, 831例接受TACE作为初始治疗的不可手术HCC患者进行了回顾性分析。其中82例降期为可手术HCC的患者纳入本研究: 43例接受了挽救性手术 (S组) , 其余39例拒绝挽救性手术的患者作为对照组 (T组) 。主要终点为总生存 (OS) 。

结果. S组和T组的中位OS分别为49个月和31个月 (P=0.027) 。S组的2年、4年和5年生存率分别为93%、47%和26%, 而T组分别为74%、18%和10% (P=0.019) 。治疗形式[风险比 (HR) : 0.337, 95%置信区间 (CI) : 0.184∼0.616, P<0.001]和TACE治疗反应 (完全缓解 (CR) vs部分缓解 (PR) HR: 3.154, 95%CI: 1.709∼5.822, P<0.001) 是生存的独立预后因素。S组的CR和PR亚组患者的中位OS分别为50和49个月, T组分别为54和24个月 (P=0.699和P<0.001) 。S组和T组有肉眼血管浸润 (MVI) 的HCC患者的中位OS分别为58和30个月 (P=0.024) 。

结论. 不可手术HCC患者在降期后进行挽救性手术的生存获益仅见于MVI或TACE后达到PR者。The Oncologist 2016;21:1442–1449

对临床实践的提示: 本研究结果提示, 对于不可手术切除的肝细胞癌患者, 在经动脉化疗栓塞 (TACE) 治疗后达到完全缓解这一预后良好的患者组中, 降期后行挽救性手术的长期转归与仅行TACE相似。与仅行TACE相比, 再行挽救性肝切除术可能有更好的长期转归, 但仅限于肉眼血管浸润或TACE治疗达到部分缓解的患者。

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the world [1]. Complete tumor resection is the generally accepted potential curative modality for HCC. However, only 30%–40% of early-stage patients are amenable to such curative therapy, because greater than 50% of all HCCs are diagnosed at an unresectable tumor stage and have a poor prognosis. These patients, therefore, must rely on palliative therapy to prolong their survival [2–4]. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a valuable and commonly applied palliative treatment for most patients with unresectable HCC [2–7]. TACE procedures can sometimes result in downstaging of HCC, allowing some unresectable lesions to become resectable because tumors shrink, satellite lesions disappear, and nontumorous tissue appears in the liver hypertrophy [7–13].

There have been numerous reports indicating that salvage liver resection or liver transplantation for unresectable tumors downstaged by TACE or other therapeutic modalities achieve excellent long-term outcomes [8–13]. However, the majority of these studies were single-arm trials and did not compare between therapeutic modalities nor did they identify the most appropriate candidates for their particular procedure. For example, patients who responded better to the treatment may have had tumors that are biologically less aggressive. Hence, results may not have reflected the true benefit of treatment. Similarly, there were some reports showing that patients who responded well to initial treatment and refused surgery had a comparable outcome to those treated with surgery [14, 15].

Multidisciplinary treatment of liver cancer was established at our institution in 2005. The team consists of surgeons, radiologists, and oncologists. Every case is discussed to decide the optimal treatment. TACE is the first-line treatment for unresectable HCC, and when downstaged, resectable HCC is observed, salvage surgery is recommended if the patient’s general condition permits. However, in our clinical practice, some patients with unresectable HCC downstaged by TACE, who refused to receive salvage resection because of unease with surgery or other reasons, underwent TACE alone. Interestingly, we found that some of these TACE-only patients also had good long-term outcomes.

Therefore, the survival benefit of salvage surgery after TACE-induced downstaging of HCC compared with TACE treatment alone for patients with unresectable HCC is unclear and controversial. The criteria for selecting patients in whom salvage surgery would most likely be of benefit are also unknown. We conducted a retrospective analysis of 82 initially unresectable HCC patients who were treated with TACE during a 10-year period to determine whether salvage surgery offers an additional overall survival (OS) benefit. We also sought to define the critical factors influencing treatment outcomes.

Patients and Methods

Patient Selection

The protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Between June 2004 and December 2014, 1,820 consecutive patients with newly diagnostic HCC managed at our center were retrospectively reviewed. The diagnosis of HCC was based on the diagnostic criteria used by the European Association for the Study of the Liver [3]. Of these patients, 679 (37%) were assessed as having early stage or resectable disease and were treated by liver surgery or local ablation; 1,141 (73%) were initially considered as unresectable. We also excluded patients exhibiting any of the following: extrahepatic metastasis and main portal vein tumor thrombosis, Child-Pugh class C or massive ascites, secondary malignancy, and unavailability of data. These unresectable HCC patients were treated by TACE as a first-line treatment and were prospectively reviewed after every course of TACE by the same multidisciplinary team. Resectability of the tumor was assessed by the same liver surgeon (L.L., who has more than 20 years of experience) and radiologist (J.L., who has more than 15 years of experience). Liver surgery was reconsidered every time a documented response to TACE was observed.

Downstaged, resectable HCC was defined as disease of any stage in which all gross tumors were deemed potentially resectable with a clear margin, as observed radiologically [8, 10]. Among the 831 local, unresectable HCC patients, 85 were significantly downstaged by TACE; 2 of these had insufficient liver function reserve and 1 received a liver transplant. The remaining 82 patients formed the population of the study. Patients were divided into 2 groups according to the pursued therapeutic strategy: 43 patients who underwent salvage surgery after downstaging of HCC (S group) and 39 patients who refused salvage liver resection and underwent only TACE treatment (T group).

Methods

TACE Procedure

TACE was performed using techniques previously described [16, 17]. Briefly, 10–20 mL of lipiodol (Guerbet, Paris, France, http://www.guerbet.com) was mixed with 20–40 mg of epirubicin (Pfizer, New York, NY, http://www.pfizer.com/) to create an emulsion. Depending on the tumor size and liver function, 2–20 mL of the emulsion was then infused into the liver tumor through a catheter. Subsequently, embolization using Gelfoam (Pfizer, Hangzhou, China, http://www.pfizer.com.cn) was performed. When blood flow slowed or a vascular cast was observed, the injection was stopped. We preferentially targeted the lobar, segmental, or subsegmental tumor-feeding artery, depending on the tumor distribution. Repeated TACE was performed at a 4- to 6-week interval on an “on-demand” basis without deterioration of liver function.

Hepatic Resection Procedure

Hepatic resection [18] was performed at 4–6 weeks after successful downstaging TACE. Anatomic resection of the liver was based on the Couinaud segments, and aimed at a gross resection margin of 1 cm from the edge of the lesions. Nonanatomic resection was performed when the tumor was at the edge of the liver. If the residual lesion was considered not resectable during surgery because of the discovery of additional lesions that were not visible on preoperative imaging, a debulking surgery was performed. The aim of the debulking surgery was to remove all macroscopic tumors while leaving behind microsatellite lesions to be treated later by locoregional therapy.

Follow-Up and Additional Treatment

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning of the chest and abdomen, liver function tests, and α-fetoprotein (AFP) measurements were performed 1 month after TACE to evaluate its effect and check for lung metastases. Additional TACE was performed for patients who did not achieve a downstaging of HCC. If downstaging of the tumor was observed, salvage surgery was recommended to every patient by the attending physician and was performed in patients who accepted. Additional treatment was performed in patients who did not accept the surgery recommendation if they still had residual viable tumors.

Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and abdomen, as well as liver function and AFP tests, were performed 1 month after liver salvage surgery to evaluate the outcome. In patients who achieved a complete response (CR) or who were tumor free, follow-up was performed every 2 months for the first 2 years. The follow-up interval was extended to every 6 months between the 2nd to 4th years after treatment, and to every 12 months after 5 years. At each follow-up session, contrast-enhanced CT scanning of the abdomen and chest, as well as liver function and AFP tests, were performed. Patients in whom recurrence or metastasis was detected were recommended for local ablation, TACE, systemic therapy, or conservative treatment was recommended, depending on the Barcelona clinic liver cancer (BCLC) staging system.

Assessments

Tumor response was assessed based on radiological evaluation according to the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors guideline [19]. AFP response was classified as either CR (normalization) or partial response (PR; a decrease by >50% of the baseline value) [17]. In HCC patients positive for AFP (a baseline AFP level >20 ng/mL), CR was assessed based on radiological evaluation and AFP normalization. Treatment complications that occurred within 4 weeks were recorded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0 [20]. OS was defined as the time from the start of treatment until death or the last follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 16.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, https://www.ibm.com). For baseline characteristics, continuous variables are described as median ± SD, and categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. The t test was used to compare continuous variables between the two groups. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables between the two groups. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate the OS between groups. Univariate analyses were performed with the log-rank test. Variables with p < .1 on univariate analysis were subjected to a multivariate analysis. The multivariate Cox model was used to identify risk factors that affected OS. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

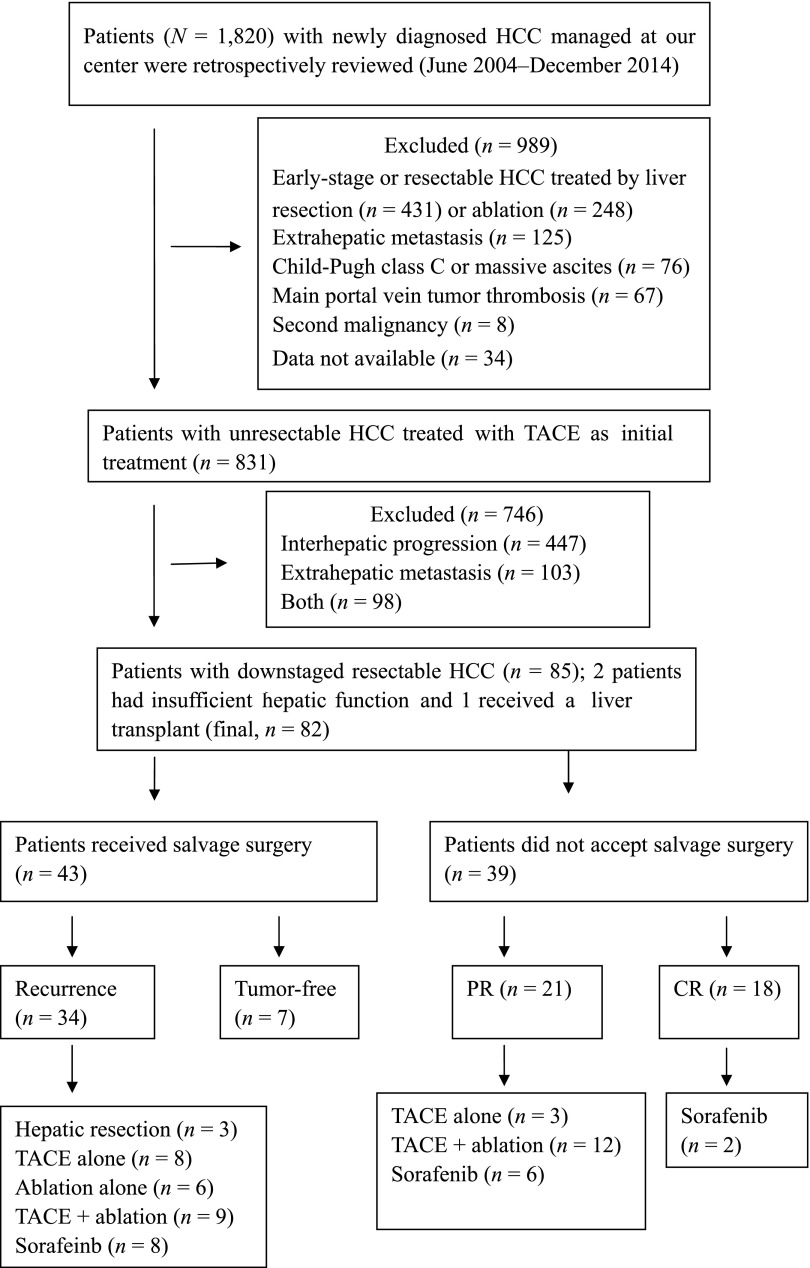

Between June 2004 and December 2014, a total of 1,820 consecutive, naïve HCC patients were retrospectively analyzed, and 1,141 patients were diagnosed as having unresectable tumors. A total of 310 patients were excluded from the first analysis. Then, 831 patients with local, unresectable HCC (intermediate, n = 411; advanced, n = 420) who were initially treated by TACE were analyzed. Of these, 85 patients were significantly downstaged by TACE; 2 of these patients had insufficient liver function reserve and 1 patient received a liver transplant. The remaining 82 patients with downstaged, resectable HCC were enrolled in the study; 43 of these received salvage surgery therapy, and the remaining 39, who refused salvage resection, underwent TACE and ablation treatment (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1. None of the variables, including the reason for initial unresectability, the cause of liver disease, or liver function, differed significantly between the two groups. The main reason for initial unresectability of tumors was bilobar involvement. The majority of the patients were male, and hepatitis B and cirrhosis were the most common underlying diseases.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the patient selection process and treatment allocation. Two patients who received liver resection died during hospitalization.

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PR, partial response; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

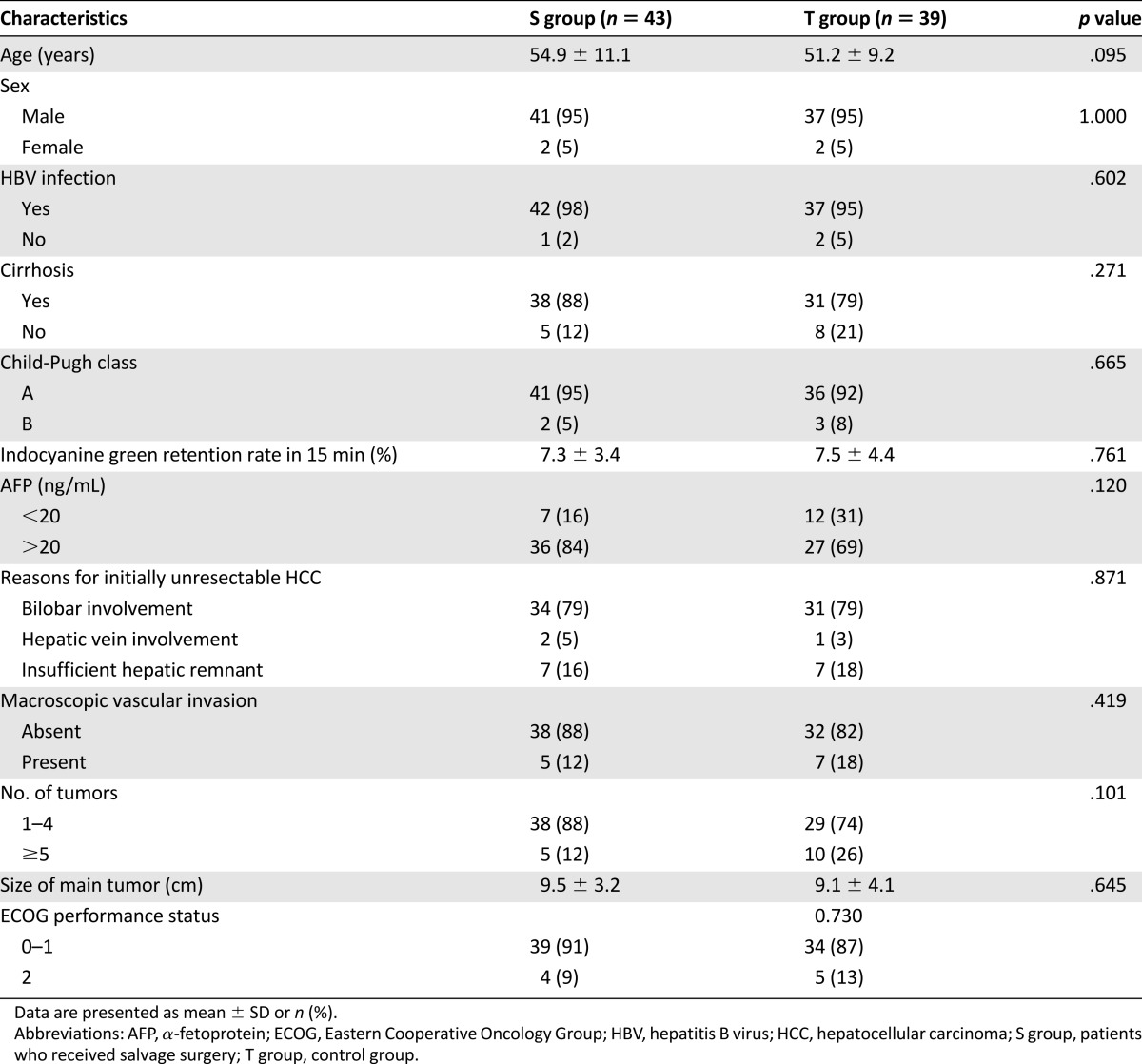

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline patient characteristics

Treatment Outcome

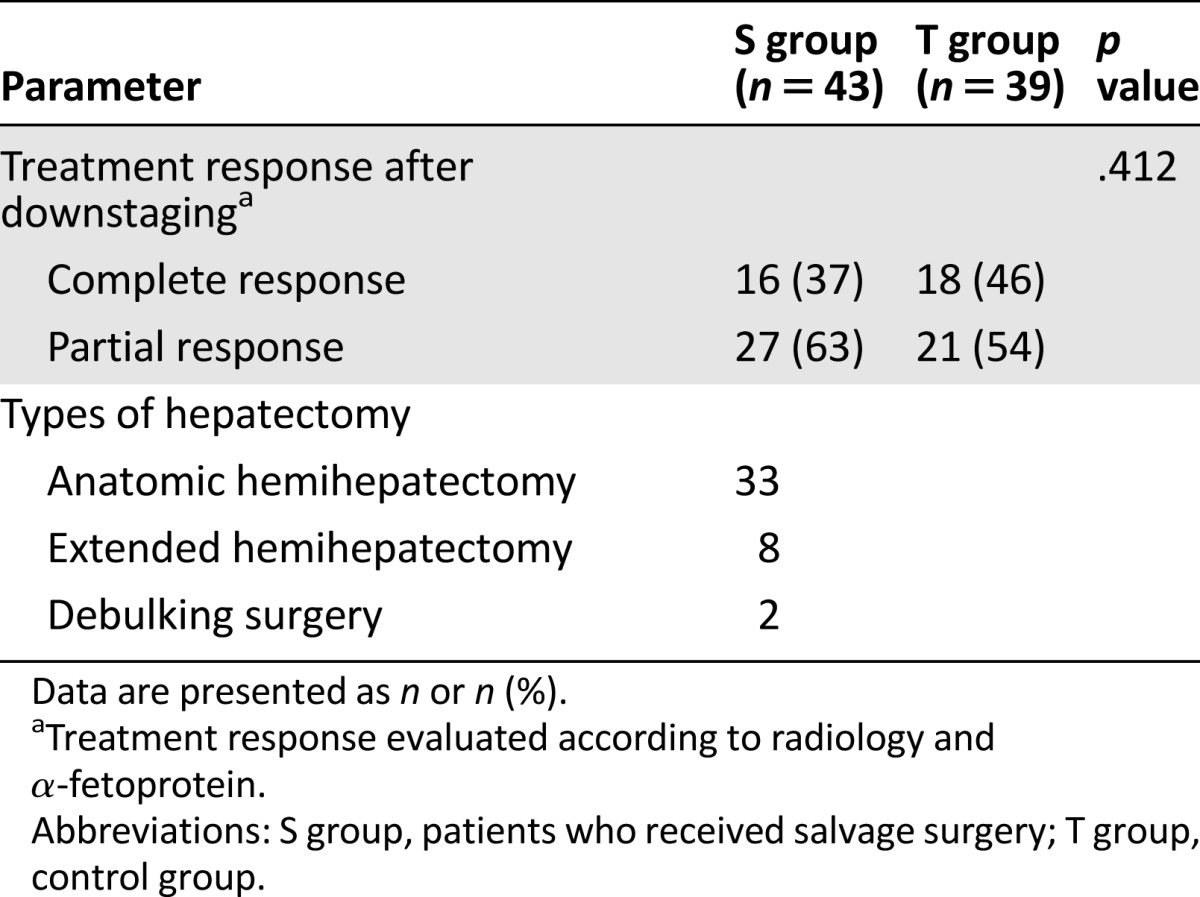

The mean number of TACE procedures per patient before downstaging in the S and T groups was 2.7 (range, 1–4) and 3.0 (range, 1–5), respectively. Based on CT measurements, the median main tumor diameter was 9.5 cm and 9.1 cm in the S and T groups before treatment, respectively. The corresponding main tumor diameters after treatment were reduced to 6.5 cm and 6.2 cm, respectively. Serum AFP levels decreased by varying extents in the 63 patients in whom levels were initially positive Table 1. AFP levels returned to normal in 13 and 14 patients in the S and T groups, respectively. After downstaging, 16 patients achieved a CR and 27 had a PR in the S group. The main reasons that tumors were deemed resectable were disappearance of some lesions, complete tumor necrosis, and shrinkage of large HCCs. The details of the treatment outcomes are shown in Table 2. Among the 39 patients in the T group, 18 patients had a CR, and 21 had a PR and received further treatment (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Treatment outcome in the S and T groups

Correlation Between Treatment and Pathologic Response

Among the 43 patients who underwent salvage liver resection, 16 had a CR with no residual tumor enhancement and achieved AFP normalization before surgery. Seven patients showed complete tumor necrosis pathologically, while the remaining nine patients showed fewer residual, viable tumor cells. The 27 patients with a PR had viable tumors.

Survival

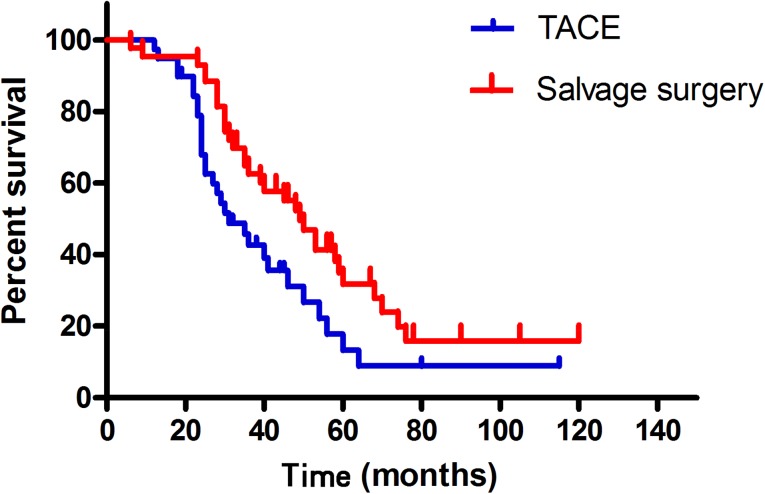

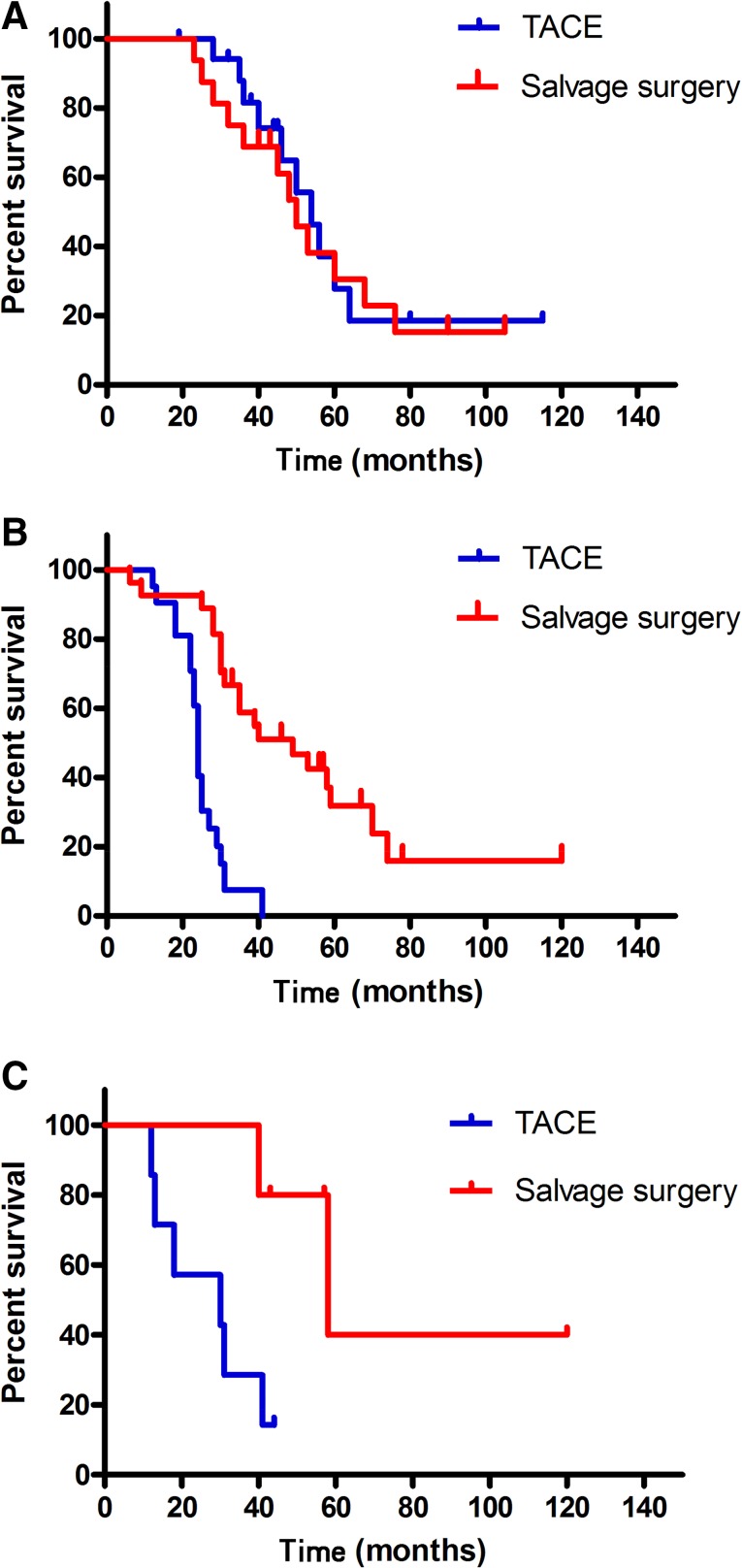

At the end of the follow-up period (August 2015), 31 patients (72%) in the S group and 29 patients (74%) in the T group had died. The mean follow-up time for these patients was 42.2 ± 22.7 months (range, 6–120 months) and the total follow-up time after initial therapy was over 10 years. Of the 43 patients who underwent liver resection, 2 died during their hospitalization. Seven patients had a tumor-free survival and 34 had a tumor recurrence, which included 3 patients with early, 18 with intermediate, 11 with advanced, and 2 with terminal disease, according to the BCLC staging system. Subsequent treatments after recurrence are shown in Figure 1. The median OS was 49 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 40.1–57.9) in the S group and 31 months (95% CI, 22.0–39.9) in the T group (Fig. 2). The difference between the two groups was significant (p = .027). The 2-, 4-, and 5-year survival rates were 93%, 47%, and 26% in the S group and 74%, 18%, and 10% in the T group, respectively (p = .019).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for patients with downstaged unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in the salvage surgery and TACE groups. The median overall survival (OS) for the salvage surgery group (n = 43) was 49 months and the median OS for the TACE group (n = 39) was 31 months (p = .027).

Abbreviation: TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

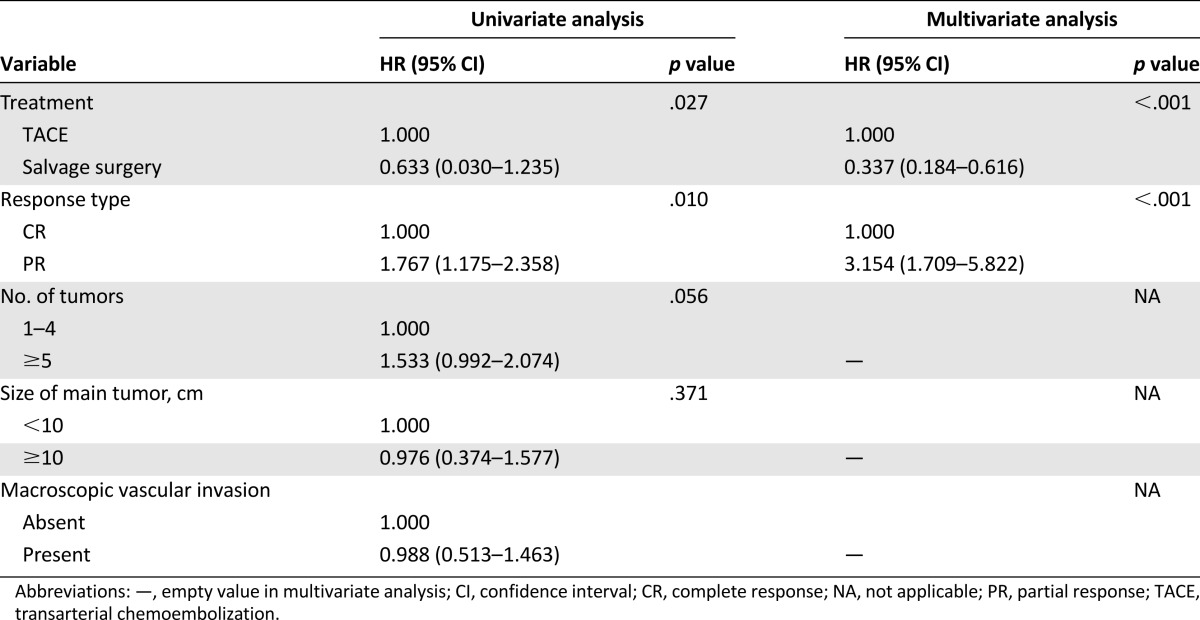

On univariate analysis, only treatment modality and response to TACE (CR or PR) after downstaging were significantly associated with survival. The number of tumors, tumor size, and presence of macroscopic vascular invasion (MVI) were not significantly associated with survival. On multivariate Cox analysis, treatment modality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.337; 95% CI, 0.184–0.616; p < .001) and response type (complete versus partial; HR, 3.154; 95% CI: 1.709–5.822; p < .001) were independent prognostic factors for OS (Table 3). Therefore, we further analyzed the OS rates between the CR and PR patient subgroups. The median OS times for patients in the CR and PR subgroups were 50 months (95% CI, 41.2–58.8) and 49 months (95% CI, 27.8–70.2), respectively, in the S group; and 54 months (95% CI, 44.8–63.2) and 24 months (95% CI, 22.9–25.1), respectively, in the T group (Fig. 3A, 3B).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for patients with downstaged unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in the salvage surgery and TACE groups. (A): Patients with a complete response. The median overall survival (OS) for the salvage surgery group (n = 16) was 50 months and that of the TACE group (n = 18) was 54 months (p = .669). (B): Patients with a partial response. The median OS for the salvage surgery group (n = 27) was 49 months and that of the TACE group (n = 21) was 24 months (p < .001). (C): Patients with macroscopic vascular invasion. The median OS for the salvage surgery group (n = 5) was 58 months and that of the TACE group (n = 7) was 30 months (p = .024).

Abbreviation: TACE: transarterial chemoembolization.

MVI is a known negative predictor for OS. Therefore, we further compared the OS rates of patients with MVI between the S group and T group. The OS times were 58 months (95% CI, 31.8–84.2) and 30 months (95% CI: 0–60.8) in the S group and T group, respectively (Fig. 3C).

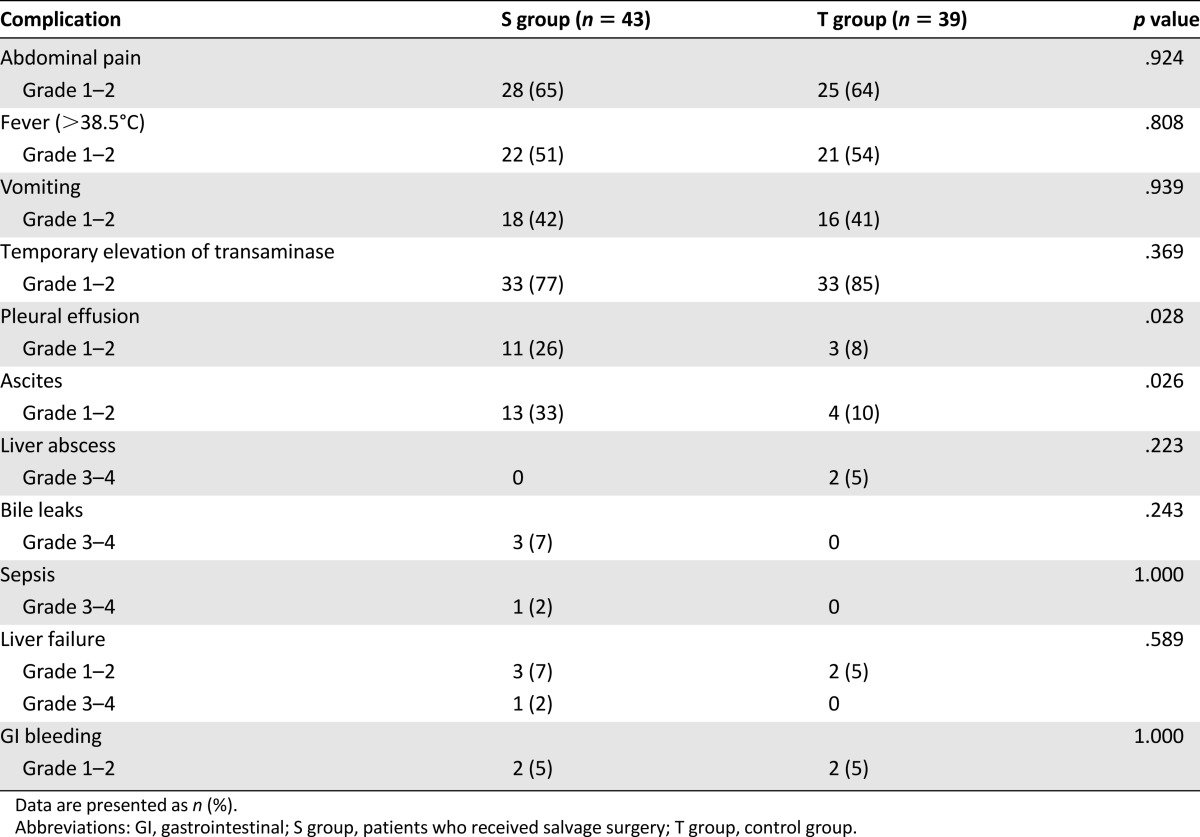

Complications

Two patients in the S group (5%) died within 4 weeks after the surgery (1 each of liver failure and sepsis). There were no deaths related to TACE. The most common adverse events after treatment were postembolization syndrome, pleural effusions, ascites, liver abscesses, bile leaks, and liver failure. Complications observed after treatment are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of complications between the S and T groups

Discussion

We assessed the long-term outcome of post-TACE salvage surgery compared with TACE alone for a specific group of patients with unresectable HCC who were downstaged by TACE. Furthermore, we defined the factors that influenced the treatment outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to date that compares the outcomes of salvage surgery versus TACE alone for patients with initially unresectable HCC that were downstaged by TACE.

We observed that salvage surgery produced a more favorable long-term outcome than TACE alone for our patients. This was likely because of the complete tumor necrosis, which, as shown histopathologically, occurred in only 16% of patients (7 of 43) after downstaging treatment. Most patients have residual viable tumors that will regrow or metastasize if they are not surgically resected. Therefore, salvage surgery may potentially extirpate such residual tumors, resulting in survival benefits. We confirmed results of previous studies that showed that salvage surgery or transplantation for downstaged tumors produces excellent outcomes in HCC [8–13], as well as colorectal liver metastases and hepatoblastoma [21, 22]. In our study, the median OS of 50 months and the 5-year survival rate of 26% are consistent with other reported outcomes (5-year survival rate ranged from 24.9% to 57%) [8].

In this study, the treatment modality and response type were identified as the independent prognostic factors for OS. Therefore, we further compared the OS between the CR and PR patient subgroups. Interestingly, we found that the OS of the S group was comparable to that of the T group in the CR subgroup. This was similar to findings of a previous study that reported the survival rates of patients who underwent initial TACE and subsequent liver resection were comparable to that of patients who responded well to TACE but refused resection [15]. On the other hand, the difference between the 2 treatments among PR patients was significant and the difference persisted for 25 months. The most likely interpretations are that (a) patients in the CR subgroup of the T group may have achieved true complete necrosis (multiple lesions in three patients all disappeared after treatment) or a very low number of residual viable tumors that can be treated further if recurrence is observed radiologically, and this resulted in patients living longer; or (b) for the PR subgroup patients, the residual viable tumors were resected, which, likewise, could have prolonged the survival time. However, MVI was not identified as a predictor of OS in our study, and subgroup survival analysis for patients with MVI demonstrated a significant difference between the S and T group (OS was 58 vs. 30 months, respectively). The most likely interpretations for this observation are (a) the small sample sizes (n = 5 and 7, respectively) did not adequately reflect the OS, and (b) we found that all patients with unresectable HCC and MVI achieved a PR to TACE, and such patients may thus be potentially cured after salvage surgery. This is consistent with the fact that the response type was an independent prognostic factor for OS in our study.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective analysis, and the data were based on patients at a single center. The reason we analyzed data from a single center is that the success of TACE strongly depends on the operator’s experience. Second, the sample size is relatively small; however, salvage surgery following tumor downstaging is possible only in a small proportion of patients with unresectable HCC (reportedly 8%–18% of patients) [8]. Third, the therapeutic options depended on the patients’ individual preferences, which likely led to bias in our population. However, the bias was limited by the fact that patients in both groups had similar baseline characteristics.

In conclusion, in patients with downstaged, resectable HCC, salvage liver resection may prolong the survival of patients with MVI or a PR to TACE. For patients with downstaged, resectable HCC and a complete response to TACE, salvage liver resection may not provide any additional survival benefits. Larger prospective studies are required to confirm this observation.

Acknowledgment

Grant support for this study was provided by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81371653).

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Yingqiang Zhang, Yu Wang, Lijian Liang, Jianyong Yang, Jiaping Li

Provision of study material or patients: Yingqiang Zhang, Guihua Huang, Yu Wang, Lijian Liang, Baogang Peng, Wenzhe Fan, Yonghui Huang

Collection and/or assembly of data: Yingqiang Zhang, Guihua Huang, Wang Yao

Data analysis and interpretation: Yingqiang Zhang, Guihua Huang, Yu Wang, Wenzhe Fan, Jiaping Li

Manuscript writing: Yingqiang Zhang, Yu Wang

Final approval of manuscript: Yingqiang Zhang, Guihua Huang, Yu Wang, Lijian Liang, Baogang Peng, Wenzhe Fan, Jianyong Yang, Yonghui Huang, Wang Yao, Jiaping Li

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forner A, Reig ME, de Lope CR, et al. Current strategy for staging and treatment: The BCLC update and future prospects. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:61–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164–1171. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:439–474. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9165-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau WY, Lai EC. Salvage surgery following downstaging of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma–a strategy to increase respectability. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3301–3309. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan J, Tang ZY, Yu YQ, et al. Improved survival with resection after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Surg. 1998;15:674–678. doi: 10.1159/000018676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau WY, Ho SK, Yu SC, et al. Salvage surgery following downstaging of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240:299–305. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133123.11932.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman WC, Majella Doyle MB, Stuart JE, et al. Outcomes of neoadjuvant transarterial chemoembolization to downstage hepatocellular carcinoma before liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2008;248:617–625. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a07d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao FY, Kerlan RK, Jr, Hirose R, et al. Excellent outcome following down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation: An intention-to-treat analysis. Hepatology. 2008;48:819–827. doi: 10.1002/hep.22412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao FY, Hirose R, LaBerge JM, et al. A prospective study on downstaging of hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1505–1514. doi: 10.1002/lt.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eberhardt WE, Pöttgen C, Gauler TC, et al. Phase III study of surgery versus definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy boost in patients with resectable stage IIIA(N2) and selected IIIB non-small cell lung cancer after induction chemotherapy and concurrent chemoradiotherapy (ESPATUE) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4194–4201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.6812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo J, Peng ZW, Guo RP, et al. Hepatic resection versus transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization as the initial treatment for large, multiple, and resectable hepatocellular carcinomas: a prospective nonrandomized analysis. Radiology. 2011;259:286–295. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Zhang F, Yang J, et al. Combination of individualized local control and target-specific agent to improve unresectable liver cancer managements: A matched case-control study. Target Oncol. 2015;10:287–295. doi: 10.1007/s11523-014-0338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Fan W, Wang Y, et al. Sorafenib with and without transarterial chemoembolization for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with main portal vein tumor thrombosis: A retrospective analysis. The Oncologist. 2015;20:1417–1424. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng B, Liang L, He Q, et al. Surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:415–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 3.0. August 9, 2006. http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf

- 21.Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G, et al. Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: A model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg. 2004;240:644–657; discussion 657–658. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141198.92114.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stringer MD, Hennayake S, Howard ER, et al. Improved outcome for children with hepatoblastoma. Br J Surg. 1995;82:386–391. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]