Abstract

We report a 59-year-old patient with malignant acanthosis nigricans associated with metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. The patient presented papillomatosis lesions that appeared to be benign on multiple skins of body folds, particularly on lips. The lesions in lips and axilla had histological characteristic appearances of acanthosis nigricans, while the masses in abdomen and pelvis were metastasis endometrial adenocarcinoma. The article highlights the importance of biopsy and histopathological diagnosis in presumed benign lesions and the role of doctors in screening for body internal tumors.

Keywords: endometrial adenocarcinoma, oral malignant acanthosis nigricans

Case report

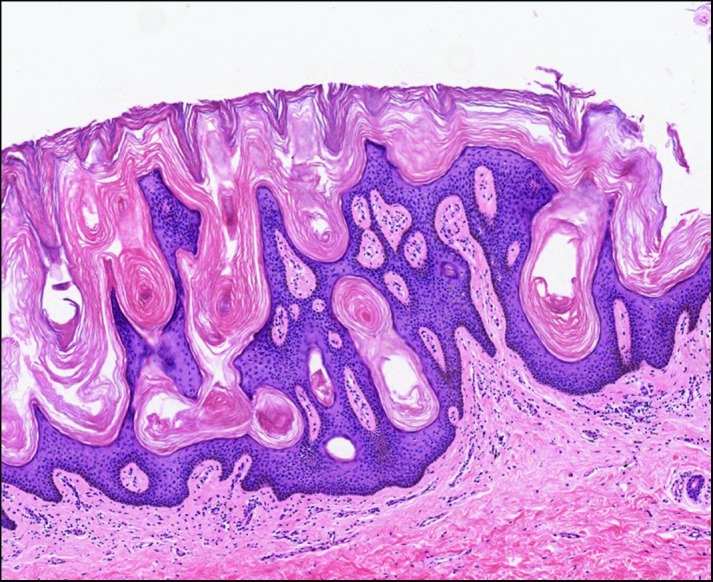

A 59-year-old woman was evaluated due to a 3-month history of oral papillomatosis on the lips. The patient had sialorrhea on account of the eversion of her tumefaction lips. The epichil was easy to bleed with a scab formation (Figure 1). Hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented skin on the face, elbows, pudendum, groins, especially in the axilla area with some warty thickening of nipples, was followed by the appearance of velvety patchy lesions in these areas (Figure 2). In the patient's history, endometrial adenocarcinoma was diagnosed and treated with surgery of hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy nine years prior. The follow-up computed tomography scan of the chest detected an enlargement of the mediastinal lymph nodes. Both the computed tomography scan and ultrasounds of the abdomen and pelvis showed several vesicle and mixed-type masses, with the largest one being 5.0 cm×4.3 cm, which was proven to be metastases carcinoma in pathological biopsy. Biopsy of lips and axilla tissue showed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, increased dermal pigmentation and papillomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis (Figure 3). Human papillomavirus DNA was not detected in the fluorescent quantitation analysis.

Figure 1.

Figure 1 Clinical appearance of lips.

Figure 2.

Figure 2 Hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented skin in the axilla area.

Figure 3.

Figure 3 Histological slide of lips showing hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, increased dermal pigmentation and papillomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis. Hematoxylin and eosin stainning, magnification ×200.

Treatment

Based on the diagnostic results, the patient was diagnosed with malignant acanthosis nigricans related to metastasis of endometrial adenocarcinoma with clinical stage-IVB according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2009).1 Due to the progress of the advanced disease, the patient was discharged home for palliative treatment and died 4 months later due to cancer progression.

Differential diagnosis

Our differential diagnosis included oral squamous cell carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, premalignant lesions, lymphoma, deep fungal infections, chronic traumatic ulcer and benign acanthosis nigricans. Oral squamous cell carcinoma presents with nuclear hyperchromatism, pleomorphism, increased nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, premature keratinzation and formation of keratin pearls. Metastatic carcinoma can be diagnosed when it is inscribed within the properties of the primitive tumor, as shown by the comparative molecular analysis or histopathological evaluation of the primitive tumor and its own metastases. The premalignant lesions and lymphoma can be ruled out histopathologically. Deep fungal infections are characterized by primary involvement of lungs and microscopic examination, which was ruled out in our case. Chronic traumatic ulcer is more frequently seen on tongue and show chronic cell infiltration on histopathological evaluation. The primary pathological manifestations of benign and malignant acanthosis nigricans are identical, characterized by hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, increased dermal pigmentation and papillomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis. The difference between these two types is the cause of the lesion, with the benign related to benign conditions, common in insulin-resistant patients, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome and Donohue syndrome, whereas the malignant are associated with internal carcinoma. Thus, the diagnosis of malignant acanthosis nigricans can be made only when there is pathological manifestation and a definite diagnosis of internal carcinoma.

Comment

Acanthosis nigricans is a brown to black, poorly defined, velvety hyperpigmentation of the skin. It is usually found in body folds, such as the posterior and lateral folds of the axilla, the neck, groin, umbilicus, forehead and other areas. As in this case, acanthosis can also be seen in lips where the condition was unusually severe.

The definitive cause for acanthosis nigricans has not yet been ascertained, although several possibilities have been suggested. Acanthosis nigricans may onset at any age. Benign acanthosis nigricans may be genetically inherited, and is associated with obesity or endocrinopathies, such as hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, acromegaly, polycystic ovary disease, insulin-resistant diabetes or Cushing's disease.2,3 The most common cause of benign acanthosis nigricans is insulin resistance, which leads to increased level of circulating insulin. Insulin spillover into the skin results in its benign abnormal increase in growth (hyperplasia of the skin). Benign acanthosis nigricans may also be seen with certain medications that lead to elevated insulin levels (e.g., glucocorticoids, niacin, insulin, oral contraceptives and protease inhibitors).2,4 Malignant acanthosis nigricans is associated with a tumor, most commonly of the stomach or gut.5 The percentage of paraneoplastic syndrome occurrence simultaneous with the intra-abdominal cancers is about 61.3%, while the rates before and after the detection of intra-abdominal cancers are 17.6% and 21%, respectively.6 The etiology and pathogenesis of malignant acanthosis nigricans remains unclear. Many pathogenic studies reveal malignant acanthosis nigricans results from carcinoma cells or its products, including transforming growth factor alpha, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor and melanocyte-stimulating hormone alpha. Tissues far from tumor could be affected by these factors via endocrine, autocrine and paracrine.7,8

Malignant acanthosis nigricans has been reported to appear abruptly and exuberantly and may be associated with a higher rate of pruritus.9 Additionally, acanthosis nigricans has similar visual characteristics (neck discoloration) with Casal collar, which is a symptom of pellagra (a nutrient deficiency disease, easily remedied with supplementation). In early stages of discoloration, it is hard for a non-trained eye to distinguish one from the other.

There is no specific treatment for acanthosis nigricans. It is important, however, to treat any underlying medical problem that may be causing these skin changes. When acanthosis nigricans is related to obesity, losing weight often improves the condition. People with acanthosis nigricans should be screened for metabolic syndrome, especially in diabetes, and internal carcinoma. Medications used to improve the appearance include Retin-A, 20% urea, alpha-hydroxyacids and lactic or salicylic acid preparations. Dermabrasion or laser therapy may help reduce the thickness of certain affected areas. Malignant acanthosis nigricans may resolve whether the causative tumor is successfully removed.2,9,10

The short survival time of this patient was largely due to delayed diagnosis and treatment. The early signs were ignored because of the nonspecificity, thus leading to the loss of a timely diagnosis and treatment. Health-care professionals who routinely diagnose more common complaints of the oral cavity may overlook the risk of a possible malignancy. Nearly 80% of malignant acanthosis nigricans cases are detected simultaneously with or before the diagnosis of the primary cancer manifestation.6 Typically florid papillomatosis lesions on oral mucosa occurred in 40% of the more than 200 malignant acanthosis nigricans cases researched.11 Above all, it is very important for health-care providers to pay attention to the oral mucous membrane lesions, which might be an indication of an internal malignancy. Physicians can usually diagnose acanthosis nigricans by simply looking at a patient's skin. A skin biopsy may be needed in unusual cases. If acanthosis nigricans occurs without obvious cause, it would be better to search for one. Blood tests, an endoscopy or X-rays may be employed to eliminate the possibility of diabetes or cancer as the cause.

References

- Creasman W. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009; 105(2): 109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J 2008; 14(9): 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafalson L, Eysaman J, Quattrin T. Screening obese students for acanthosis nigricans and other diabetes risk factors in the urban school-based health center. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011; 50(8): 747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo L, Biscozzi AM, Mastrandrea Vet al. Acanthosis nigricans vulgaris. A marker of hyperinsulinemia. Eur J Pediat Dermatol 2003; 13(5): 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Brinca A, Cardoso JC, Brites MM et al. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans maligna revealing gastric adenocarcinoma. An Bras Dermatol 2011; 86 (3): 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Pagano M et al. Oral acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and sign of Leser–Trélat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43(7): 530–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzner U, Ramsauer J, Petzoldt W et al. [Acanthosis nigricans maligna. Case report and review of the literature]. Hautarzt 1998; 49 (1): 41–47. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M. Transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF alpha)-producing gastric carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of TGF alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol 1997; 32(1): 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Schwartz RA. Juvenile acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57(3): 502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor S. Diagnosis and treatment of acanthosis nigricans. Skinmed 2010; 8(3): 161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedano HO, Gorlin RJ. Acanthosis nigricans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987; 63(4): 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]