Abstract

Sub-gingival anaerobic pathogens can colonize an implant surface to compromise osseointegration of dental implants once the soft tissue seal around the neck of an implant is broken. In vitro evaluations of implant materials are usually done in monoculture studies involving either tissue integration or bacterial colonization. Co-culture models, in which tissue cells and bacteria battle simultaneously for estate on an implant surface, have been demonstrated to provide a better in vitro mimic of the clinical situation. Here we aim to compare the surface coverage by U2OS osteoblasts cells prior to and after challenge by two anaerobic sub-gingival pathogens in a co-culture model on differently modified titanium (Ti), titanium-zirconium (TiZr) alloys and zirconia surfaces. Monoculture studies with either U2OS osteoblasts or bacteria were also carried out and indicated significant differences in biofilm formation between the implant materials, but interactions with U2OS osteoblasts were favourable on all materials. Adhering U2OS osteoblasts cells, however, were significantly more displaced from differently modified Ti surfaces by challenging sub-gingival pathogens than from TiZr alloys and zirconia variants. Combined with previous work employing a co-culture model consisting of human gingival fibroblasts and supra-gingival oral bacteria, results point to a different material selection to stimulate the formation of a soft tissue seal as compared to preservation of osseointegration under the unsterile conditions of the oral cavity.

Keywords: biofilm, co-culture, dental implant, osteoblasts, sub-gingival pathogens, titanium-zirconium alloy

Introduction

Biomaterial implants are indispensable in modern medicine for the restoration of function, but roughly 5% fail due to infection.1 Biomaterial-associated infection is hard to cure, as the biofilm mode of growth protects adhering bacteria against the host immune system and antibiotic treatment. Bacteria can gain access to an implant surface at different points in time after implantation and through different routes.2 A common route of infection is through peri-operative contamination,3,4 which can give rise to clinical signs of infection years after implantation.3,5 Alternatively, implants are at risk of becoming colonized by haematogenous spreading of bacteria from infection elsewhere in the body.6 Depending on local antibiotic guidelines, implant patients receive antibiotics prior to dental treatment7 in order to prevent haematogenous spreading of oral bacteria to an implant site. The oral pathway along which implants throughout the body can become infected raises the question of how dental implants can survive in an unsterile environment with infection rates that are roughly equal to the 5% seen in environments that are sterile by nature.8,9

The first line of defense of dental implants is the soft tissue seal surrounding the implants neck.10 The soft tissue seal has to form immediately after implantation against the challenge of the oral microflora in a combat named ‘the race for the surface'.3 If bacterial colonization prevails over tissue integration, the implant is lost, while tissue integration offers the best protection of an implant against invading pathogens. Although an appealing concept, it has taken over 20 years before co-culture studies emerged enabling to study the simultaneous behaviour of tissue cells and bacteria on biomaterial surfaces. Co-culture studies have been performed under static conditions,11 in macroscopic12 or microfluidic13 flow chambers and have superseded monoculture studies with either tissue cells or bacteria.14,15 In a peri-operative contamination model, tissue cells have to integrate a bacterially contaminated implant surface,16 while in a post-operative model cells covering an implant surface are challenged by bacteria.17 Supra-gingival oral bacteria can easily contaminate the neck of an implant during implantation and have the ability to form biofilms on different implant materials including titanium (Ti), titanium-zirconium (TiZr) alloys and zirconium-oxides (ZrO2; ‘zirconia'), regardless of their roughness or hydrophobicity.11 Also, all implant materials could be covered by human gingival fibroblasts for 80%–90% of their surface areas within 48 h of growth. Yet, human gingival fibroblasts lost the race for the surface against different supra-gingival bacterial strains on nearly all bacterially contaminated implant materials in a peri-operative contamination model, except on the smoothest Ti variants. Co-culture studies therewith demonstrate that smooth Ti surfaces provide the best opportunities for a soft tissue seal to form on bacterially contaminated implant surfaces, in line with results from the few clinical human studies carried out to this end.18

In peri-implantitis19 the soft tissue seal is broken, which is accompanied by a compositional change in the local microflora, and anaerobic periodontopathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia, have been identified as late colonizers from dental implants showing clinical signs of infection.18,20 Although peri-implantitis initially involves the soft tissue seal, in more progressed states, it also involves an attack on the bone cells adhering to the osseointegratable part of an implant leading to bone loss and possibly loss of an entire implant. Osseointegration of dental implants is assured by a tight fit21 and choosing materials with good osseointegrative surface properties. Ti has long been the material of choice,22 but is unsuitable as an implant material in narrow interdental spaces or in case of severe maxillary resorption.23,24,25 Ti alloys, especially TiZr alloys, possess improved mechanical strength, making them suitable for use as small-diameter implants.26 ZrO2 ceramics are also used as an alternative for Ti due to their high mechanical strength, chemical stability and resistance to corrosion, in addition to their aesthetic advantage of better matching the natural tooth colour.27 Ti alloys and ZrO2 have all been compared with Ti for their osseointegrative properties, either in miniature pigs26,28,29 or rabbits30 for periods of time up to 2 months. In general,31 these studies are low-powered. A systematic review concluded that ‘ZrO2 may have the potential to be a successful implant material',32 while osseointegration of Ti alloys may be called similar to Ti depending in part on the surface modification applied and resulting surface morphology and hydrophobicity.28,33,34

None of these studies have been geared towards comparing osseointegration of different implant materials upon challenging the interface between their osseointegratable part and bone with periodontal pathogens. While animal or clinical studies may well be impossible due to the necessary duration of such studies and statistical limitations, in vitro evaluation of these materials has only been done on the basis of monoculture studies with either bacteria35,36 or cells15,37,38 but never in a post-operative, co-culture model.17 A post-operative, co-culture model distinguishes itself from a peri-operative model: in a post-operative model, an implant surface is fully covered by tissue cells after which tissue integration is challenged by bacteria, while in a peri-operative model tissue cells have to try to cover a bacterially contaminated implant surface.

The aim of this study was to compare the surface coverage of osteoblasts cells on different dental implant materials after growth in absence and presence of a challenge with two anaerobic sub-gingival periodontopathogens (P. intermedia ATCC 49046 or P. gingivalis ATCC 33277) in a post-operative, co-culture model. The implant materials include differently modified Ti surfaces, as well as TiZr alloys and ZrO2, as previously compared in a peri-operative, co-culture model involving human gingival fibroblasts and a variety of different supra-gingival strains.11

Materials and methods

Implant materials

All implant materials have been evaluated before in a peri-operative, co-culture model11 and were received under a Materials Transfer Agreement from Institut Straumann AG (Basel, Switzerland) as 5 mm diameter discs with a thickness of 1 mm. Implant materials comprise Ti (cold-worked, grade 4), TiZr alloy (15% (m/m) Zr) and ZrO2 (ZrO2 with Y-TZP), modified according to different procedures, indicated as:

P: mirror-polished with finally a 0.04 μm SiO2 suspension and cleaned with a Deconex (a commercial detergent for metal cleaning obtained from Borer Advanced Cleaning Solutions, Zuchwil, Switserland) solution, followed by concentrated nitric acid and water.

M: ground to mimic the machined part of the implant and washed with Deconex solution, followed by concentrated nitric acid and water.

MA: ground and then acid-etched with a boiling mixture of concentrated HCl and H2SO4 (or hot hydrofluoric acid in case of ZrO2) and rinsed with concentrated nitric acid and water.

modMA: ground and acid-etched with HCl/H2SO4, as described above, but rinsed with water only under N2 protection and directly stored individually in glass containers, filled with an isotonic NaCl solution, protected by N2 filling.

M, MA, modMA and P modifications were all applied to Ti, whereas TiZr alloy and ZrO2 were only modified according to M and modMA (TiZr alloy) or MA (ZrO2). M, MA and P modified discs were individually packed in aluminum foil and sealed in plastic. All discs were sterilized in their respective packaging by γ-irradiation at 25–42 kGy. Surface properties of the different implant materials are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Physical-chemical properties of differently modified Ti, TiZr alloys and ZrO2 implant surfaces involved in this study.

| Physical properties | Chemical composition/% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Ra/µm | θw/° | C | Ti | Zr | Oin oxide | Oother |

| Ti-P | 0.01 | 55 | 52 | 11 | – | 28 | 9 |

| Ti-M | 0.07 | 92 | 52 | 11 | – | 25 | 11 |

| Ti-MA | 0.66 | 81 | 44 | 14 | – | 31 | 10 |

| Ti-modMAa,b,c | 0.73 | 2 | 42 | 11 | – | 27 | 9 |

| TiZr alloy-M | 0.13 | 72 | 51 | 10 | 2 | 27 | 10 |

| TiZr alloy-modMAa,b | 0.24 | 23 | 41 | 9 | 2 | 26 | 10 |

| ZrO2-M | 0.09 | 53 | 50 | – | 12 | 21 | 13 |

| ZrO2-MA | 0.77 | 82 | 45 | – | 16 | 28 | 11 |

Ra, surface roughness; θw, water contact angle.Data taken from Zhao et al.11.

Contains about 5% Na and Cl.

Contains 2%–4% N.

Contains 2% Ca.

Bacterial strains and culturing

Two anaerobic, sub-gingival pathogens known to be involved in periodontitis, P. intermedia ATCC 49046 and P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 were used in this study. Strains were streaked onto blood agar plates and incubated for 48 h anaerobically (85% N2, 10% H2 and 5% CO2) at 37 °C. One colony was inoculated into 5 mL brain heart infusion broth (BHI; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) medium (with 5 g·L–1 yeast, 5 mg·L–1 hemin and 10 mg·L–1 menadion) and grown for 24 h under anaerobic conditions. Bacteria were counted in a Bürker-Türk counting chamber and the bacterial culture was diluted with sterile adhesion buffer (50 mmol·L−1 potassium chloride, 2 mmol·L−1 potassium phosphate, 1 mmol·L−1 calcium chloride, pH 6.8) to a suspension with a concentration of 104 or 106 bacteria per mL.

Bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation in monoculture studies

Discs of each implant material were placed in 48-well plates and 10 µL droplets of a bacterial suspension (106 bacteria per mL) were placed on each disc under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, the bacterial suspensions were removed by dipping the discs three times in sterile adhesion buffer after which discs with adhering bacteria were inserted into modified culture medium (for details see section below on ‘Osteoblast cells culturing and harvesting') and biofilm formation was allowed for 96 h under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. Growth medium was exchanged after 48 h.

After 96 h of growth, the discs were dipped three times in sterile adhesion buffer and biofilms were stained with a vitality staining solution, containing 3.34 mmol·L−1 SYTO 9 and 20 mmol·L−1 propidium iodide (live/dead stain, BacLight; Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands) in sterile ultrapure water. Staining was done in the 48-well plates for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. Next, biofilms were examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Leica DMRXE with a confocal TCS SP2 unit) equipped with a water objective (HCX APO L 40.0 × 0.80 W) using 488 nm excitation and emission filters of 500–550 nm and 605–720 nm to reveal live or dead bacteria, respectively. Images were taken over the depth of a biofilm in sequential steps of 0.8 μm. Subsequently, the stacks of images acquired were analysed for the total biofilm volume per unit area with the program ‘COMSTAT'.39 In short, the expression ‘total biovolume' refers to the volume occupied per unit substratum area by dead and live bacteria in a biofilm. Accordingly, its unit is µm3 per µm2. Biovolume is calculated from the number of green (live bacteria) and red (dead bacteria) in an image stack multiplied by the voxel size (cubic pixel size).

Osteoblast cells culturing and harvesting

U2OS osteosarcoma cells (ATCC HTB-94) were routinely grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/low glucose (DMEM/LG) supplemented with 10% (V/V) fetal bovine serum, 0.2 mmol·L−1 ascorbic acid-2-phosphate (DMEM/LG-complete) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. At 70%–80% confluence the U2OS cells were passaged using a trypsin-elhylene diaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution (Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands). Thus, grown cells were used in all mono- and co-culture studies. Importantly, in co-culture studies, U2OS osteosarcoma cells were initially grown in DMEM/LG-complete in 5% CO2, pursuing survival of U2OS osteoblasts and simultaneous growth with oral sub-gingival anaerobes in a modified culture medium under anaerobic conditions.

To develop such a modified culture medium suitable for bacterial growth and survival of U2OS osteoblasts under anaerobic conditions, bacterial (BHI+) and cellular growth media (DMEM/LG-complete) were combined in different ratios and the growth of P. intermedia ATCC 49046, P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 or U2OS osteoblasts were monitored over time in monocultures.

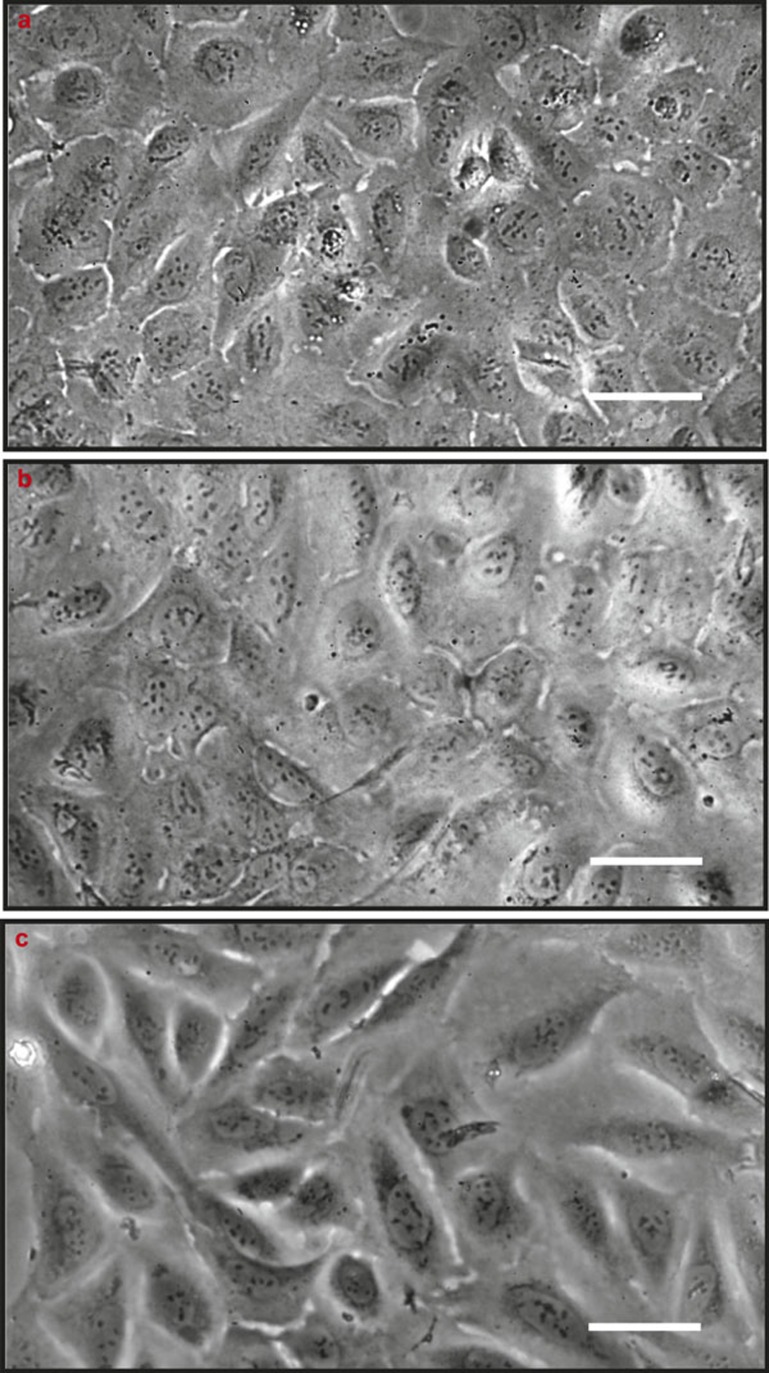

With respect to U2OS osteoblast growth, suspensions of cells (3 × 104 mL–1 in DMEM/LG-complete) were added in 48-well plates made of tissue culture polystyrene. After growth for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, survival of the U2OS osteoblasts was determined under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C after replacing DMEM/LG-complete by modified culture media with different ratios of DMEM/LG-complete and BHI+. After 24 or 48 h, the morphology of the U2OS cells was assessed using phase-contrast microscopy, yielding the conclusion that cells survived anaerobic conditions in modified culture medium with maximally 10% BHI+ added for at least 48 h (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phase contrast micrographs of U2OS osteoblasts initially grown aerobically with pursued further growth under anaerobic conditions. (a) U2OS osteoblasts initially grown in 100% DMEM/LG-complete at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h in tissue culture polystyrene wells; (b, c) pursued further growth for 24 or 48 h in modified culture medium with 10% BHI+ added under anaerobic conditions. Bar markers indicate 50 μm. BHI, brain heart infusion; DMEM/LG, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium low glucose.

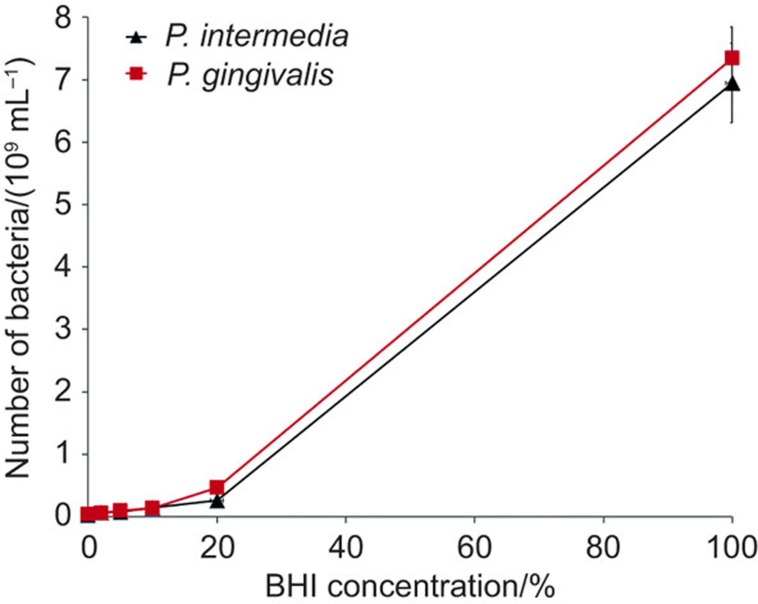

With respect to the growth of the sub-gingival anaerobes in modified culture medium, bacteria of each strain were first grown in 5 mL BHI+ for 24 h, after which 0.5 mL of these cultures was used to inoculate 4.5 mL of modified culture media with different ratios of DMEM/LG-complete and BHI+ for 24 or 48 h under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. After 48 h, numbers of bacteria per mL (see Figure 2) of the different cultures were compared. Both sub-gingival anaerobes showed limited growth in DMEM/LG-complete, while bacterial growth increased with increasing percentage of BHI+. Since U2OS osteoblasts could not survive in media with higher percentages of BHI+ than 10%, a modified culture medium was chosen that consisted of DMEM/LG-complete with 10% BHI+ added. In the remainder of this study, therefore, DMEM/LG-complete with 10% BHI+ will be denoted as ‘modified culture medium'.

Figure 2.

Growth curve of P. gingivalis and P. intermedia as a function of the percentage BHI+ in modified culture medium. P. gingivalis and P. intermedia were grown anaerobically in a mixture of BHI+ and DMEM/LG-complete, anaerobically. 0% BHI means 100% DMEM/LG-complete. BHI, brain heart infusion; DMEM/LG, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium low glucose.

Adhesion, spreading and growth of U2OS osteoblasts in monoculture studies

Discs of each implant material were placed in 48-well plates and 1 mL of a cell suspension (3 × 104 mL–1) in DMEM/LG-complete was added. Cells were grown 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Then, DMEM/LG-complete was replaced by modified culture medium and put for 48 h under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. Subsequently, discs with adhering cells were prepared for immuno-cytochemical staining to assess U2OS osteoblast spreading and number of adhering cells. For fixation, growth medium was removed and replaced by 3.7% paraformaldehyde in cytoskeleton stabilization buffer (0.1 mol·L−1 Pipes, 1 mmol·L−1 ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 4% (m/m) polyethylene glycol 8000, pH 7.0). Adhering cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mmol·L−1 potassium phosphate, 0.15 mol·L−1 NaCl, pH 7.0) for 3 min, and stained with 2 mg·mL–1 phalloidin- tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) and 4 mg·mL–1 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. After that, the discs were incubated in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin for 5 min. Subsequently, discs were examined with fluorescence microscopy (Leica DM4000; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Images (five images on different locations) were taken and the number of adhering cells per unit area and the average area per spread cell were determined using Scion image software to yield the total coverage of the substratum surface by U2OS osteoblasts. All experiments were performed in triplicate on each implant surface.

Challenging osteoblast layers with anaerobic sub-gingival bacteria in a co-culture model

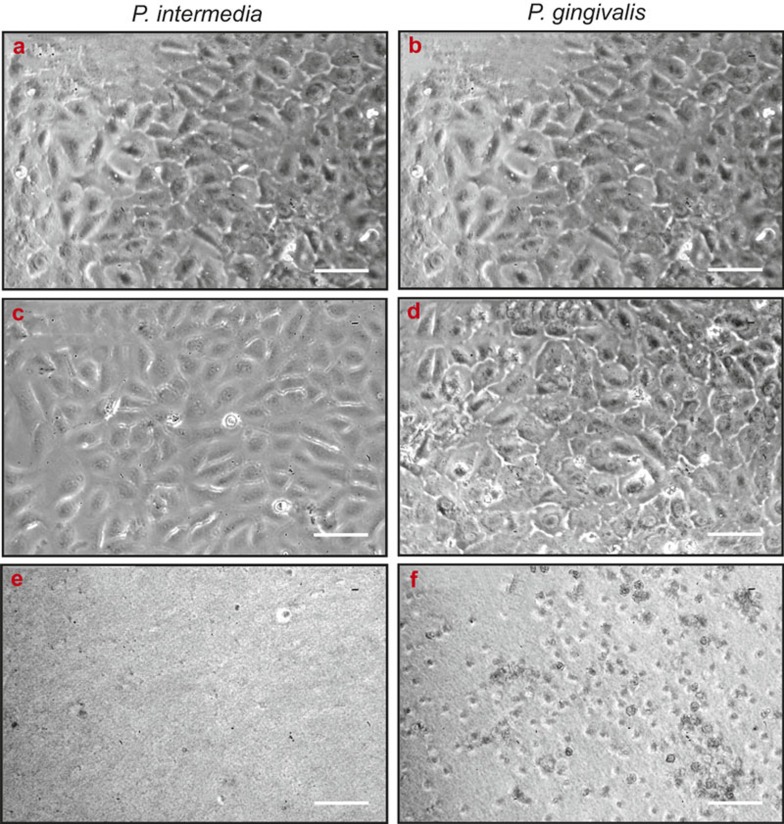

A previous study with a staphylococcal strain challenging U2OS monolayers on poly(methyl methacrylate) has shown that initial coverage by tissue cells needs to be above a threshold coverage of above 40%,17 while furthermore too high a bacterial challenge concentration kills all adhering cells, impeding comparisons of different materials. Therefore, U2OS monolayers were grown for 24 h to a surface coverage of 80%–100% in DMEM/LG-complete at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in tissue culture polystyrene wells, representative of a near-fully osseointegrated implant. DMEM/LG-complete was replaced with modified culture medium and challenged with one of the two oral sub-gingival pathogens in modified culture medium at a bacterial concentration of 104 or 106 bacteria per mL for 48 h, after which the morphologies of the adhering cells were examined by phase-contrast microscopy. U2OS cells did not demonstrate any morphological change in response to a bacterial challenge at 104 mL–1 for either P. intermedia ATCC 49046 or P. gingivalis ATCC 33277, but at 106 mL–1 near complete cellular detachment was observed after challenge with P. intermedia ATCC 49046 (Figure 3). After challenge with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277, adhering U2OS rounded up in response to bacterial challenge (see also Figure 3). Accordingly, a bacterial challenge concentration of 104 mL–1 was chosen for the experiments.

Figure 3.

Phase-contrast micrographs of U2OS osteoblasts challenged with different concentrations of sub-gingival pathogens. U2OS osteoblasts initially grown in 100% DMEM/LG-complete at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h in tissue culture polystyrene wells, and after pursued further anaerobic growth for 48 h in modified culture medium in absence and presence of different concentrations of P. intermedia ATCC 49046 or P. gingivalis ATCC 33277. (a, b) No bacteria; (c, d) ×104 mL−1bacteria; (e, f) ×106 mL−1 bacteria. Bar markers indicate 25 μm. DMEM/LG, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium low glucose.

Next, U2OS cells were grown in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere to a surface coverage of 80%–100% on all material surfaces and growth continued in absence and presence of a challenge with either P. intermedia ATCC 49046 or P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 under anaerobic conditions, as described above. After 48 h, U2OS cells were fixed, stained with phalloidin-TRITC and DAPI and analysed as described above for surface coverage and cell numbers. All experiments were performed in triplicate on each implant materials.

Statistical analyses

Biovolumes by the different bacterial strains and U2OS cells interaction with the different implant materials in monoculture or co-culture experiments are presented as means with standard deviations. All statistical comparisons between multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey's multiple comparison tests to compare each material variant with the other variants in the same material group. To analyse differences in surface coverage and cell adhesion number in absence and presence of a bacterial challenge, surface coverage and adhesion numbers were compared by two tailed Student's t-test. To analyse the magnitude of these differences on variants within the same material group, one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison tests were carried out. In addition, the average differences in surface coverages and cell numbers grown in absence or presence of a bacterial challenge were compared between the group of four Ti variants and the other groups of materials using Mann–Whitney tests. A P-value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. GraphPad Prism 6 statistical software was used for all analyses.

Results

Biofilm formation on different dental implant materials in monocultures

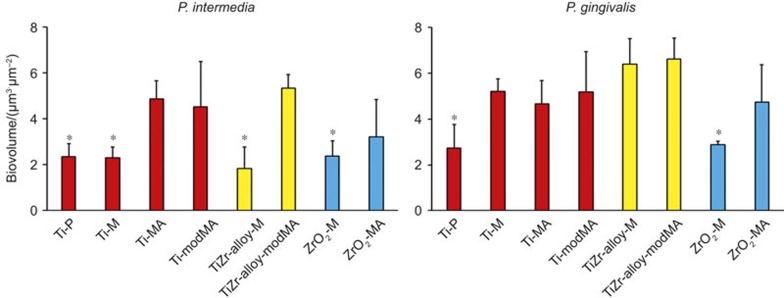

The biovolumes of P. intermedia and P. gingivalis across the different materials are summarized in Figure 4. P. intermedia biofilms were generally of equal thickness or thinner than P. gingivalis biofilms on the same implant material. For P. intermedia, significantly (P < 0.05) less biofilm was found on the smoother surfaces compared to rougher variants from the same material (compare Table 1). For P. gingivalis a less pronounced effect of surface roughness was seen.

Figure 4.

Biovolumes of P. intermedia ATCC 49046 and P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 biofilms after 96 h of growth on different implant surfaces. Error bars represent standard deviations over three experiments with different discs of each material and separately cultured bacteria. *Significantly (P < 0.05) different from all other surfaces in the same group of materials.

Adhesion, spreading and growth of U2OS osteoblasts in monocultures

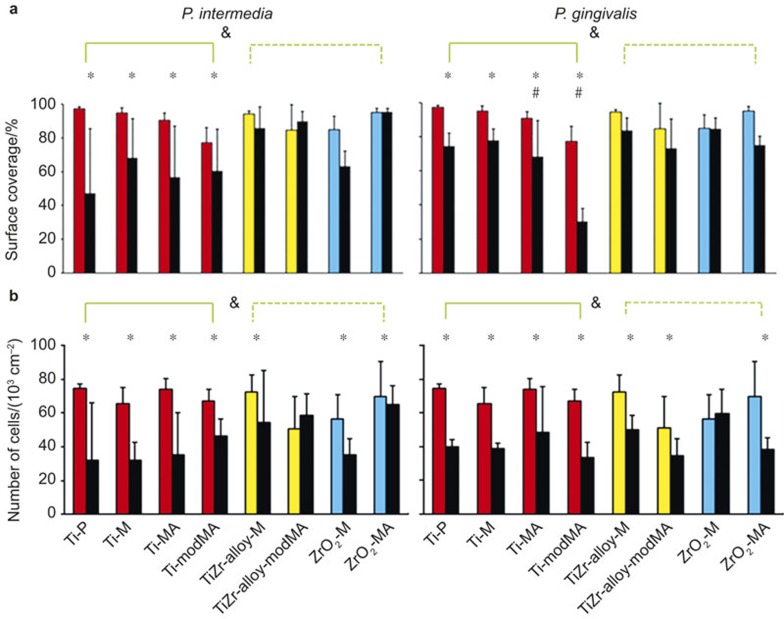

U2OS osteoblasts showed similar surface coverage on all implant surfaces (no significant differences across materials and their variants) with surface coverages of between 80% and 100% after 24 h growth in DMEM/LG-complete in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and 48 h continued growth in modified culture medium under anaerobic conditions (see Figure 5a). Differences existed in the number of cells adhering (see Figure 5b) and the lowest number of cells was found on TiZr alloy-modMA and ZrO2-M, indicating that the spread area per cell was highest on relatively rough (Ra = 0.24 µm) and hydrophilic (θw = 23°) TiZr alloy-modMA (1 667 µm2) and smoother (Ra = 0.09 µm), but more hydrophobic (θw = 53°) ZrO2-M (1 156 µm2).

Figure 5.

U2OS osteoblast surface coverage and cell number on different implant materials grown in absence (coloured columns) or presence (adjacent black columns) of a challenge by sub-gingival oral bacteria. (a) Surface coverage; (b) number of cells. Error bars indicate standard deviations over triplicate experiments with separately grown cells and bacteria. * Significant (P < 0.05) differences in surface coverages and cell numbers in absence versus presence of a bacterial challenge (black and colored columns respectively) on the same material. # Magnitudes of the differences in surface coverages and cell numbers in absence versus presence of a bacterial challenge on the same material are significantly (P < 0.05) higher than on the other Ti variants. & Magnitudes of the differences in surface coverages and cell numbers in absence versus presence of a bacterial challenge on the same material are significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in the other groups of materials, indicated by the green lines.

Co-culture of U2OS osteoblasts with anaerobic sub-gingival bacteria on different dental implant materials

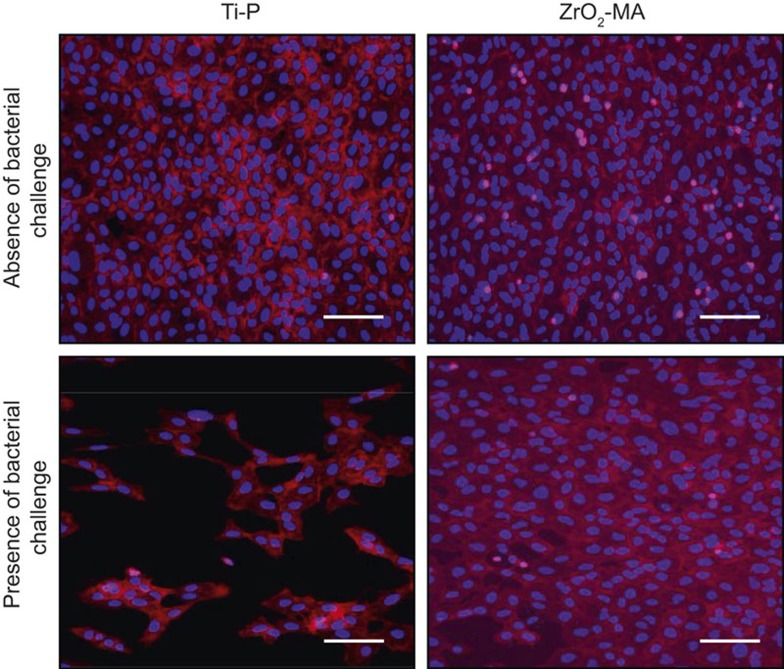

Figure 6 illustrates the effects of a U2OS osteoblast monolayer grown in absence and presence of a challenge with P. intermedia ATCC 49046. As can be seen, high numbers of U2OS osteoblasts adhere in absence of a bacterial challenge both on Ti-P (Ra = 0.01 µm; θw = 55°) and ZrO2-MA (Ra = 0.77 µm; θw = 82°). Despite this similarity between both materials in surface coverage and number of adhering cells in absence of a bacterial challenge, U2OS osteoblasts show a considerably less surface coverage in presence of a bacterial challenge on Ti-P than on ZrO2-MA, where cell surface coverage was almost similar in absence and presence of a bacterial challenge.

Figure 6.

Example of immune-cytostained images of U2OS osteoblasts grown on Ti-P and ZrO2-MA surfaces. U2OS osteoblasts were grown for 24 h in DMEM/LG-complete at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and subsequently grown for 48 h in anaerobic conditions in modified culture medium in absence and presence of a challenge with P. intermedia. Bar markers indicate 100 μm. DMEM/LG, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium low glucose.

Quantitative effects of growing U2OS osteoblast layers on the different materials under bacterial challenge can be seen by comparing the coloured columns in Figure 5 with the black ones. Both the presence of P. intermedia and P. gingivalis, significantly (P < 0.05) decreases U2OS osteoblast surface coverage on the Ti variants, but no reductions due to growth in presence of a bacterial challenge are seen on TiZr alloys and ZrO2 variants (Figure 5a). Note, however, that these decreases were less pronounced but still significant (P < 0.05) for P. gingivalis than for P. intermedia. In line, the numbers of adhering U2OS cells generally decreased most upon a bacterial challenge on the Ti variants (P < 0.05), irrespective of the strain involved (Figure 5b).

Discussion

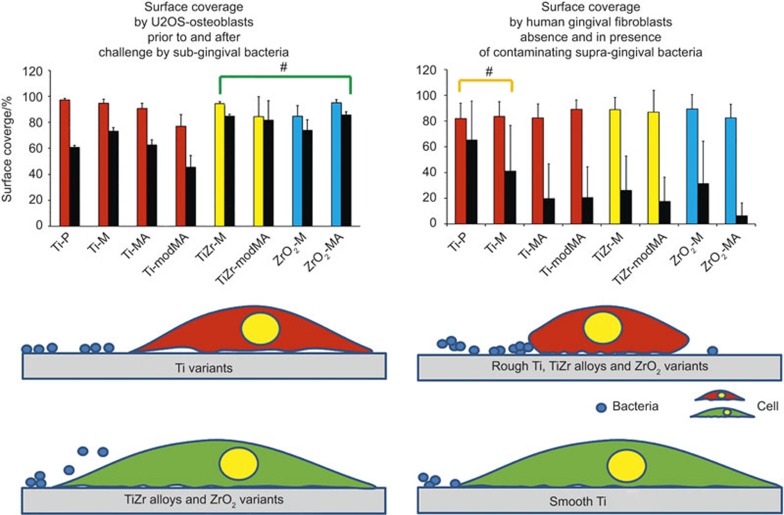

Osseointegration of dental implants is assured by a tight fit and osseointegrative material selection. Material selection for optimal osseointegration, however, also involves the requirement of material surface properties on which bone cells can effectively withstand a pathogenic challenge. Clinical studies to evaluate the infection resistance of different dental implant materials are scarce and not seldom under-powered.31 In this paper, we rely on a post-operative, co-culture model consisting of U2OS osteoblasts and sub-gingival, anaerobic periodontopathogens to demonstrate that adhering U2OS osteoblasts are more readily displaced from differently modified Ti surfaces by challenging sub-gingival pathogens than from TiZr alloys and ZrO2 variants. TiZr alloys and ZrO2 variants are thus to be preferred over Ti for the osseointegratable part of dental implants.

Monocultures on biofilms formation show that P. gingivalis biofilms are thicker than of P. intermedia, with P. intermedia preferring rough surfaces over smooth ones with little or no preferences for a specific surface chemistry or hydrophobicity of the implant material. In a comparative study40 of P. gingivalis and P. intermedia adhesion to smooth Ti surfaces extending over a 22 h time period, P. gingivalis was found to adhere in lower numbers (4.0 × 108 cm–2) than P. intermedia (6.4 × 108 cm–2), which is opposite to what is observed in the current study after growth. However, this difference is less than a factor of two, which makes it extremely small in view of the fact that bacterial doubling times in a biofilm are in the orders of several tens of minutes.41

U2OS osteoblasts grew equally well on all materials when in monoculture. Hydrophobicity and roughness of the different materials did not show any difference in surface coverage of U2OS cells, except for the very hydrophilic Ti-modMA exhibiting the lowest surface coverage. However, surface coverage depends on the number and spread area of adhering cells and the equal surface coverages observed across the different materials comes into existence through different pathways. U2OS osteoblasts spread best on a relatively rough and hydrophilic TiZr alloy variant and relatively smooth and hydrophobic ZrO2 variant. This is in line with results on spreading of human osteoblast-like MG63 cells, for which it was concluded that spreading depended on an interplay between surface roughness and materials chemistry.42 In summary, a materials preference for the osseointegratable part of a dental implant cannot be derived from monoculture studies with neither bacteria nor cells, emphasizing the need for a proper co-culture model.

A co-culture model in which anaerobic bacteria are grown together with tissue cells has never been employed before and could only be realized by first growing a layer of U2OS osteoblasts on a material in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere and then changing the conditions to anaerobic as required for co-culturing with anaerobic bacteria. U2OS osteoblasts remained to look morphologically healthy despite oxygen deprivation (see Figure 6) and in fact oxygen is not a prerequisite for tissue cells to survive.43 Hypoxia is known to reduce osteoblast alkaline phosphatase activity and expression of mRNAs for alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that collagen fibrils deposited by osteoblasts cultured in 2% O2 were less organized and less abundant than in 20% O2 cultures. Importantly, hypoxia did not increase the apoptosis of osteoblasts.43 This is an important property of osteoblasts that allowed us to challenge them in a co-culture model under anaerobic conditions with sub-gingival oral pathogens.

In our anaerobic co-culture model, adhering U2OS osteoblasts as on the osseointegratable parts of an implant, on average withstand a challenge by sub-gingival pathogens better on TiZr alloys and ZrO2 variants than on Ti variants (see Figure 7, left panels) regardless of roughness indicating an overriding effect of materials chemistry.42 Challenges with either of the two periodontopathogens have about the same negative impact on the coverage of the implant surfaces by osteoblasts, despite the fact that in monoculture studies P. gingivalis forms more extensive biofilms than P. intermedia. Hypothetically, we propose that U2OS osteoblasts adhere more strongly to TiZr alloys and ZrO2 than to pure Ti. Osteoblasts-like cell adhesion in monoculture has been found to be enhanced on ZrO2 compared to pure Ti and also the gene expression of integrin β1, ERK1/2 and c-fos was higher on ZrO2 than on Ti,44 although other monoculture studies showed no difference in initial cell response to Ti and ZrO2.45,46 Previous work11 employing an aerobic, peri-operative, co-culture model consisting of human gingival fibroblasts and supra-gingival oral bacteria, pointed out that a soft tissue seal as needed on the neck part of an implant, develops more readily on bacterially contaminated, smooth Ti surfaces (see also Figure 7, right panels). Therewith our previous11 and present co-culture studies on dental implant materials indicate that different requirements should be set to the materials properties for the neck versus the osseointegratable part of a dental implant.

Figure 7.

Battles occurring on the osseointegratable part of a dental implant between an existing layer of adhering U2OS osteoblasts and challenging periodontopathogens (left panel) and on the neck of an implant between gingival fibroblasts and contaminating oral bacteria adhering to the implant surface (right panel). Left panel: a comparison of the surface coverage by U2OS cells on dental implant materials grown prior to (coloured bars) and after (black bars) of a challenge by sub-gingival, oral bacterial strains. Data represent averages over P. intermedia ATCC 49046 and P. gingivalis ATCC 33277. On TiZr alloys and ZrO2 variants, adhering osteoblasts withstand a challenge by sub-gingival bacteria more effectively than on Ti variants, regardless of surface roughness (green coloured, well-spread cell versus red cell), making TiZr alloys and ZrO2 variants most suitable for the osseointegratable part of an implant. Right panel: a comparison of the surface coverage by human gingival fibroblasts on dental implant materials grown in absence (coloured bars) and presence (black bars) of contamination by adhering supra-gingival, oral bacteria (Streptococcus oralis J22, Streptococcus mitis BMS, Streptococcus salivarius HB and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923). Data represent averages over the four strains indicated (data taken with permission from Zhao et al.11). Displacement of contaminating supra-gingival bacteria from smooth Ti variants (green coloured, well-spread cell versus red, rounded-up cell) is easier than from the other implant materials included in this study, making smooth Ti variants most suitable for the neck of an implant. #These materials on average perform better than the other materials with respect to a bacterial challenge of an existing cellular layer or integration of a material in the presence of contaminating bacteria.

Whereas we previously argued that our conclusion on material selection for the implant neck on basis of infection-resistance coincided with the few, low-powered clinical human study results available,18 this remains to be demonstrated for the conclusion drawn from our co-culture study on the osseointegratable part. Favourable conclusions on all implant materials evaluated in this study can be found in the literature. A systematic review32 concluded that there were no differences in the rate of osseointegration between the different implant materials in animal experiments, while scientific clinical data for ceramic implants in general and for ZrO2 implants in particular were considered insufficient to recommend ceramic implants for routine clinical use. In vivo studies in miniature pigs28 and New Zealand rabbits30 concluded that TiZr alloy (sandblasted and acid-etched) implant surfaces had a similar potential for clinical applications as clinically proven Ti surfaces (sandblasted and acid-etched).28 Another study in miniature pigs26 concluded that TiZr alloy with a hydrophilic, sandblasted and acid-etched surface showed similar or even stronger bone tissue responses than the Ti control, while another study in miniature pigs suggested that unloaded, sandblasted ZrO2 and sandblasted and acid-etched Ti implants osseointegrated comparably within a healing period of four weeks.29 Unfortunately, no studies on these different materials have been found geared towards a comparison of the infection-resistance of osseointegration.

In summary, this in vitro co-culture study suggests that for the osseointegratable parts of dental implants, TiZr alloys and ZrO2 variants are the preferred materials with respect to maintaining osseointegration under conditions of pathogen challenge. Previously, we demonstrated that for the implant neck, smooth Ti was the material of choice with respect to rapid formation of an effective soft tissue seal in the presence of bacterial contamination. Differential requirements for the different parts of a dental implants have never been proposed from the perspective of infection control but may lead to a new generation of dental implants with reduced clinical infection rates.

Acknowledgments

The authors are greatly indebted to Edward Rochford, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands, for his help in preparing the schematics in Figure 7. The materials used in this study were provided free of charge by Institut Straumann AG, Basel, Switzerland, under a Materials Transfer Agreement. H.J.B. is director-owner of SASA BV. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to authorship and/or publication of this article. Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not construed as necessarily representing views of the funding organization or their employer(s).

References

- Grainger DW, Van der Mei HC, Jutte PC et al. Critical factors in the translation of improved antimicrobial strategies for medical implants and devices. Biomaterials 2013; 34(37): 9237–9243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busscher HJ, Van der Mei HC, Subbiahdoss G et al. Biomaterial-associated infection: locating the finish line in the race for the surface. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4(153): 153rv10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gristina AG. Biomaterial-centered infection: microbial adhesion versus tissue integration. Science 1987; 237(4822): 1588–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher N, Sofianos D, Berkes MB et al. Prevention of perioperative infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89(7): 1605–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabe M, Botto H, Cek M et al. Preoperative assessment of the patient and risk factors for infectious complications and tentative classification of surgical field contamination of urological procedures. World J Urol 2012; 30(1): 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: prosthetic-joint-associated infections. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006; 20(6): 1045–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf B, Jandali-Rifai M, Susarla S et al. Do perioperative antibiotics decrease implant failure? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 69: 2345–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gynther GW, Kondell PA, Moberg LE et al. Dental implant installation without antibiotic prophylaxis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1998; 85: 509–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C, Zhao B, Ren Y et al. The implant infection paradox: why do some succeed when others fail? Eur Cell Mater 2015; 29: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brakel R, Meijer GJ, Verhoeven JW et al. Soft tissue response to zirconia and titanium implant abutments: an in vivo within-subject comparison. J Clin Periodontol 2012; 39(10): 995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Van der Mei HC, Subbiahdoss G et al. Soft tissue integration versus early biofilm formation on different dental implant materials. Dent Mater 2014; 30(7): 716–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiahdoss G, Grijpma DW, Van der Mei HC et al. Microbial biofilm growth versus tissue integration on biomaterials with different wettabilities and a polymer-brush coating. J Biomed Mater Res A 2010; 94(2): 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Wang H, Kaplan JB et al. Microfluidic approach to create three-dimensional tissue models for biofilm-related infection of orthopaedic implants. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2010; 17(8): 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CH, Chang YY, Huang HL et al. Characterization and antibacterial performance of ZrCN/amorphous carbon coatings deposited on titanium implants. Thin Solid Films 2011; 520(4): 1525–1531. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zitelli JP, TenHuisen KS et al. Differential response of staphylococci and osteoblasts to varying titanium surface roughness. Biomaterials 2011; 32(4): 951–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiahdoss G, Kuijer R, Grijpma DW et al. Microbial biofilm growth vs. tissue integration: “the race for the surface” experimentally studied. Acta Biomater 2009; 5(5): 1399–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiahdoss G, Kuijer R, Busscher HJ et al. Mammalian cell growth versus biofilm formation on biomaterial surfaces in an in vitro post-operative contamination model. Microbiology 2010; 156(10): 3073–3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalampakis G, Leonhardt A, Rabe P et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of peri-implantitis cases: a retrospective multicentre study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012; 23(9): 1045–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglundh T, Persson L, Klinge B. A systematic review of the incidence of biological and technical complications in implant dentistry reported in prospective longitudinal studies of at least 5 years. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29(Suppl 3): 197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson GR, Samuelsson E, Lindahl C et al. Mechanical non-surgical treatment of peri-implantitis: a single-blinded randomized longitudinal clinical study. II. Microbiological results. J Clin Periodontol 2010; 37(6): 563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrektsson T, Branemark PI, Hansson HA et al. Osseointegrated titanium implants. Requirements for ensuring a long-lasting, direct bone-to-implant anchorage in man. Acta Orthop Scand 1981; 52(2): 155–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geetha M, Singh A, Asokamani R et al. Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants–a review. Prog Mater Sci 2009; 54(3): 397–425. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Kim HM, Kim CS et al. Long-term retrospective study of narrow implants for fixed dental prostheses. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013; 24(8): 847–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallman M. A prospective study of treatment of severely resorbed maxillae with narrow nonsubmerged implants: results after 1 year of loading. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2001; 16(5): 731–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourauel C, Aitlahrach M, Heinemann F et al. Biomechanical finite element analysis of small diameter and short dental implants: extensive study of commercial implants. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2012; 57(1): 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlow J, Dard M, Kjellson F et al. Evaluation of a new titanium-zirconium dental implant: a biomechanical and histological comparative study in the mini pig. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2012; 14(4): 538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn DB. The use of a zirconia custom implant-supported fixed partial denture prosthesis to treat implant failure in the anterior maxilla: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2008; 100(6): 415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulacic N, Bosshardt DD, Bornstein MM et al. Bone apposition to a titanium-zirconium alloy implant, as compared to two other titanium-containing implants. Eur Cell Mater 2012; 23(1): 273–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadlinger B, Hennig M, Eckelt U et al. Comparison of zirconia and titanium implants after a short healing period. A pilot study in minipigs. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 39(6): 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen B, Zhu F, Li Z et al. The osseointegration behavior of titanium-zirconium implants in ovariectomized rabbits. Clin Oral Implants Res 2014; 25(7): 819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompen E. The impact of the type and configuration of abutments and their (repeated) removal on the attachment level and marginal bone. Eur J Oral Implantol 2012; 5(Suppl): S83–S90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreiotelli M, Wenz HJ, Kohal RJ. Are ceramic implants a viable alternative to titanium implants? A systematic literature review. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009; 20(Suppl 4): 32–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares A, Domken O, Dard M et al. Peri-implant soft tissues around implants with a modified neck surface. Part 1. Clinical and histometric outcomes: a pilot study in minipigs. J Clin Periodontol 2013; 40(4): 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz F, Mihatovic I, Golubovic V et al. Experimental peri-implant mucositis at different implant surfaces. J Clin Periodontol 2014; 41(5): 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidlin PR, Muller P, Attin T et al. Polyspecies biofilm formation on implant surfaces with different surface characteristics. J Appl Oral Sci 2013; 21(1): 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MC, Llama-Palacios A, Fernandez E et al. An in vitro biofilm model associated to dental implants: structural and quantitative analysis of in vitro biofilm formation on different dental implant surfaces. Dent Mater 2014; 30(10): 1161–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisarek M, Roguska A, Andrzejczuk M et al. Effect of two-step functionalization of Ti by chemical processes on protein adsorption. Appl Surf Sci 2011; 257(19): 8196–8204. [Google Scholar]

- Polyakov AV, Semenova IP, Valiev RZ. High fatigue strength and enhanced biocompatibility of UFG CP Ti for medical innovative applications. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2014; 63(1): 012113. [Google Scholar]

- Heydorn A, Nielsen AT, Hentzer M et al. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 2000; 146(Pt 10): 2395–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuula H, Kononen E, Lounatmaa K et al. Attachment of oral gram-negative anaerobic rods to a smooth titanium surface: an electron microscopy study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2004; 19(6): 803–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottenbos B, Van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Initial adhesion and surface growth of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa on biomedical polymers. J Biomed Mater Res 2000; 50(2): 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrovcova M, Hanus J, Drabik M et al. Effect of different surface nanoroughness of titanium dioxide films on the growth of human osteoblast-like MG63 cells. J Biomed Mater Res A 2012; 100(4): 1016–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utting JC, Robins SP, Brandao-Burch A et al. Hypoxia inhibits the growth, differentiation and bone-forming capacity of rat osteoblasts. Exp Cell Res 2006; 312(10): 1693–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Sun J, Xu Y et al. Biological behavior of osteoblast-like cells on titania and zirconia films deposited by cathodic arc deposition. Biointerphases 2012; 7(1): 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita D, Machigashira M, Miyamoto M et al. Effect of surface roughness on initial responses of osteoblast-like cells on two types of zirconia. Dent Mater J 2009; 28(4): 461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong SH, Lee H, Pae A et al. Gene expression of MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells on titanium and zirconia surface. J Adv Prosthodont 2013; 5(4): 416–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]