Abstract

Objective

To compare two summary indicators for monitoring universal coverage of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health care.

Methods

Using our experience of the Countdown to 2015 initiative, we describe the characteristics of the composite coverage index (a weighted average of eight preventive and curative interventions along the continuum of care) and co-coverage index (a cumulative count of eight preventive interventions that should be received by all mothers and children). For in-depth analysis and comparisons, we extracted data from 49 demographic and health surveys. We calculated percentage coverage for the two summary indices, and correlated these with each other and with outcome indicators of mortality and undernutrition. We also stratified the summary indicators by wealth quintiles for a subset of nine countries.

Findings

Data on the component indicators in the required age range were less often available for co-coverage than for the composite coverage index. The composite coverage index and co-coverage with 6+ indicators were strongly correlated (Pearson r = 0.73, P < 0.001). The composite coverage index was more strongly correlated with under-five mortality, neonatal mortality and prevalence of stunting (r = −0.57, −0.68 and −0.46 respectively) than was co-coverage (r = −0.49, −0.43 and −0.33 respectively). Both summary indices provided useful summaries of the degrees of inequality in the countries’ coverage. Adding more indicators did not substantially affect the composite coverage index.

Conclusion

The composite coverage index, based on the average value of separate coverage indicators, is easy to calculate and could be useful for monitoring progress and inequalities in universal health coverage.

Résumé

Objectif

Comparer deux indicateurs synthétiques pour le suivi de la couverture universelle en matière de santé reproductive, maternelle, néonatale et infantile.

Méthodes

En nous appuyant sur l'expérience que nous avons acquise dans le cadre de l'initiative Compte à rebours 2015, nous décrivons les caractéristiques de l'indice de couverture composé (moyenne pondérée de huit interventions préventives et curatives tout au long du cycle continu de soins) et de l'indice de co-couverture (total cumulatif de huit interventions préventives dont doivent bénéficier toutes les mères et tous les enfants). En vue d'une analyse et de comparaisons approfondies, nous avons extrait des données de 49 enquêtes démographiques et sanitaires. Nous avons calculé le taux de couverture pour chacun des deux indices synthétiques, puis nous les avons corrélés entre eux et avec des indicateurs de résultats en matière de mortalité et de dénutrition. Nous avons également stratifié les indicateurs synthétiques par quintile de richesse pour un sous-ensemble de neuf pays.

Résultats

Les données relatives aux indicateurs des composantes dans la tranche d'âge requise étaient moins souvent disponibles pour la co-couverture que pour l'indice de couverture composé. Une forte corrélation a été établie entre l'indice de couverture composé et la co-couverture avec 6 indicateurs ou plus (Pearson r = 0,73, P < 0,001). L'indice de couverture composé a été plus fortement corrélé avec la mortalité des enfants de moins de cinq ans, la mortalité néonatale et la prévalence du retard de croissance (r = −0,57, −0,68 et −0,46 respectivement) que la co-couverture (r = −0,49, −0,43 et −0,33 respectivement). Les deux indices synthétiques ont donné un aperçu utile des niveaux d'inégalité entre les pays en matière de couverture sanitaire. L'ajout d'autres indicateurs n'a pas eu une incidence majeure sur l'indice de couverture composé.

Conclusion

L'indice de couverture composé, basé sur la valeur moyenne de différents indicateurs de couverture, est facile à calculer et pourrait être utile pour suivre les progrès et les inégalités en matière de couverture sanitaire universelle.

Resumen

Objetivo

Comparar dos indicadores de resumen para controlar la cobertura universal de atención sanitaria reproductora, materna, obstétrica e infantil.

Métodos

A través de la experiencia de la iniciativa “Cuenta atrás para 2015”, se describen las características del índice de cobertura compuesto (una media ponderada de ocho intervenciones preventivas y curativas a lo largo de una atención continua) y el índice de cocobertura (una cuenta acumulativa de ocho intervenciones preventivas que deberían recibir todas las madres y niños). Para obtener un análisis profundo y comparaciones, se ha recopilado información de 49 encuestas sobre demografía y salud. Se ha calculado el porcentaje de cobertura para ambos índices de resumen y se han correlacionado entre ellos y con los indicadores de resultados de mortalidad y desnutrición. También se han estratificado los indicadores de resumen con quintiles de riqueza en un subconjunto de nueve países.

Resultados

La información sobre los indicadores de componentes del grupo de edades necesario podía obtenerse con menos asiduidad para el índice de cocobertura que para el índice de cobertura compuesto. El índice de cobertura compuesto y el índice de cocobertura con más de 6 indicadores se correlacionaban muy estrechamente (r de Pearson = 0,73, P < 0,001). El índice de cobertura compuesto se correlacionaba más estrechamente con la mortalidad de menores de cinco años, la mortalidad de neonatos y la prevalencia de la deficiencia del crecimiento (r = −0,57, −0,68 y −0,46 respectivamente) que el índice de cocobertura (r = −0,49, −0,43 y −0,33 respectivamente). Ambos índices de resumen ofrecieron resúmenes útiles de los grados de poca adecuación de la cobertura de los países. El hecho de añadir más indicadores no afectó de forma significativa al índice de cobertura compuesto.

Conclusión

Es fácil calcular el índice de cobertura compuesto, según el valor medio de los indicadores de cobertura individuales, y podría resultar de utilidad para controlar el progreso y la poca adecuación de la cobertura sanitaria universal.

ملخص

الغرض

المقارنة بين مؤشرين موجزين لرصد التغطية العالمية للإنجاب وصحة الأم والوليد والرعاية الصحية للأطفال.

الطريقة

بالاعتماد على خبرتنا بالعد التنازلي لمبادرة عام 2015، فإننا نصف خصائص مؤشر التغطية المركب (متوسط مُرجح للإجراءات الثمانية الوقائية والعلاجية بجانب استمرارية الرعاية) ومؤشر التغطية المشتركة (العد التراكمي للإجراءات الثمانية الوقائية التي ينبغي على جميع الأمهات والأطفال تلقيها). وللحصول على تحليل ومقارنة متعمقين، فقد استخرجنا البيانات من 49 دراسة ديموغرافية وصحية. وقمنا بحساب نسبة تغطية المؤشرين الموجزين، وربطهما مع بعضها ومع كل مؤشرات نتائج الوفيات ونقص التغذية الأخرى. كما قمنا بتطبيق المؤشرات الموجزة عن طريق أخماس الثروة لمجموعة فرعية من تسعة بلدان.

النتائج

كانت البيانات الصادرة بشأن المؤشرات المركبة في الفئة العمرية المطلوبة أقل توفرًا في الغالب بالنسبة التغطية المشتركة وذلك بالمقارنة مع مؤشر التغطية المركب. وقد ارتبط مؤشر التغطية المركب والتغطية المشتركة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بأكثر من 6 مؤشرات ( معامل ارتباط بيرسون = 0.73، بمعدل الاحتمال < 0.001). وقد ارتبط مؤشر التغطية المركب بشكل أكبر بمعدل وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة ووفيات الأطفال حديثي الولادة وانتشار التقزم ( معدل ارتباط = -0.57، و-0.68 و-0.46 على التوالي) بالمقارنة مع التغطية المشتركة (حيث بلغ معدل الارتباط = -0.49، و-0.43 و-0.33 على التوالي). قدم كلاً من المؤشرين الموجزين ملخصات مفيدة لدرجات عدم المساواة في التغطية بين البلدان. ولم تؤثر إضافة المزيد من المؤشرات تأثيرًا كبيرًا على مؤشر التغطية المُركّب.

الاستنتاج

يعتمد مؤشر التغطية المُركب على متوسط قيمة مؤشرات التغطية المنفصلة، كما يسهل حسابه وقد يكون مفيدًا لرصد التقدم المحرز وأوجه عدم المساواة في التغطية الصحية العالمية.

摘要

目的

旨在比较两个生育、孕产妇、新生儿和儿童医疗保健普遍覆盖率综合监测指数。

方法

根据我们在“2015 年倒计时”方案方面的经验,我们描述了综合覆盖率指数(连续护理过程中八种预防与治疗干预的加权平均数)和共同覆盖率指数(所有母亲和儿童都应该接受的八种预防干预的累计计数)的特征。 为了深度分析和比较,我们提取了来自 49 项人口与健康调查的数据。 我们计算了这两个综合指标的百分比占有率,对其进行了相互对照,并与死亡和营养不良的结果指标进行了对照。 我们使用财富五分位数对九个国家构成的子集的综合指数进行了分层。

结果

与综合覆盖率指数相比,可用于共同覆盖率指数的所需年龄段组指标数据更难获取。 综合覆盖率指数和带有 6 个以上指标的共同覆盖率指数之间的关联性非常强 (Pearson r = 0.73, P < 0.001)。 五岁以下儿童死亡率、新生儿死亡率和发育迟缓类疾病的患病率与综合覆盖率指数之间的关联性(分别为 r = −0.57, −0.68 和 0.46)比与共同覆盖率指数之间的关联性(分别为 r = −0.49, 0.43 和 0.33)更强。 这两个综合指数都有助于总结各国覆盖率的不平衡程度。 加入更多指标并不会从实质上影响综合覆盖率指数。

结论

基于单个覆盖率指标平均值的综合覆盖率指数方便计算,并且有助于监测普遍医疗保健覆盖率的进程及不均衡性。

Резюме

Цель

Сравнить два сводных показателя мониторинга всемирной охраны репродуктивного здоровья, материнства, новорожденных и детей других возрастных групп.

Методы

Используя собственный опыт инициативы «К 2015 году», авторы описывают параметры составного индекса охвата (средневзвешенный показатель восьми профилактических и оздоровительных мероприятий в ходе профилактики) и индекса совместного охвата (кумулятивная частота этих восьми профилактических мероприятий для всех матерей и детей). Для проведения подробного анализа и сравнений были получены данные из 49 демографических и медико-санитарных обследований. Авторы рассчитали в процентах степень охвата для двух суммарных показателей и определили, как они коррелируют друг с другом и с результирующими показателями смертности и недоедания. Кроме того, для подгруппы, состоящей из девяти стран, сводные показатели были разбиты по квинтилям по уровню благосостояния.

Результаты

Данные по показателям составляющих для требуемого возрастного диапазона были менее доступны для индекса совместного охвата, чем для составного индекса охвата. Между составным индексом охвата и совместным охватом, включающим шесть и более показателей, была установлена сильная корреляция (коэффициент корреляции Пирсона r = 0,73, P < 0,001). Корреляция, установленная между составным индексом охвата и смертностью детей младше пяти лет, ранней детской смертностью и распространенностью задержки роста (r = −0,57; −0,68 и −0,46 соответственно), была сильнее, чем между ними и совместным охватом (r = −0,49; −0,43 и −0,33 соответственно). Оба сводных показателя позволили получить полезную информацию о степени неравномерности охвата в исследуемых странах. Добавление дополнительных показателей не оказало существенного влияния на составной индекс охвата.

Вывод

Составной индекс охвата, основывающийся на среднем значении отдельных показателей охвата, прост для расчета и может применяться для контроля улучшения или неравномерности в мировом обеспечении услугами системы здравоохранения.

Introduction

Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health were important elements of the millennium development goals (MDGs). MDG 4 targeted the reduction of child mortality, while MDG 5 focused on the improvement of maternal health.1 Because most low- and middle-income countries failed to reach the targets of the MDGs by 2015,2 maternal, newborn and child health goals remained as sustainable development goals (SDGs) 3.1 and 3.2, to be achieved by 2030. Also relevant to the health of mothers and children are SDG 3.7 on sexual and reproductive health and SDG 3.8 on universal health coverage.3

Monitoring the coverage of interventions in maternal and child health continues to be central to assessing progress towards development goals.4 Our experience with the Countdown to 2015 initiative (which tracks progress in interventions in 75 countries) is directly relevant to monitoring the four SDGs mentioned above.4,5 Starting with 35 coverage indicators monitored in 2005,6 the Countdown list grew to 73 indicators by 2015.5 Reporting separately on each indicator proved to be useful at the country and global level for tracking progress, evaluating programmes and planning future actions. However, reporting on tens of indicators generated an overwhelming amount of data and failed to provide a comprehensive picture of progress in scaling up essential health interventions. Recent calls have been made for a focus on a small number of indicators for reporting trends in intervention coverage.7 To address these needs, the Countdown team has experimented with two summary measures of coverage: the composite coverage index and the co-coverage index.

Both indices comprise eight indicators of coverage of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health care, with five indicators in common. The composite coverage index was first proposed in 2008 as the weighted average coverage of eight preventive and curative interventions received along the continuum of maternal and child care.8,9 The index is calculated at group level, either for a whole country or by subgroups such as wealth quintiles or geographical regions. The co-coverage indicator, proposed in 2005, is a simple count of how many preventive interventions are received by individual mother–child pairs, out of a set of eight interventions.10 Co-coverage is limited to preventive interventions that are recommended for every child and pregnant woman to achieve universal health coverage. Because curative interventions are only required for children who are ill, these are not included in the co-coverage index, for which the denominator includes all children.

Universal health coverage is defined in terms of access to and receipt of essential interventions, and of financial risk protection.3 In this study we describe and compare the characteristics of the composite coverage index and the co-coverage index for monitoring universal health coverage in reproductive, maternal, newborn and child care. In-depth analyses aimed to: (i) correlate the summary indices with each other and with outcome indicators of mortality and undernutrition; (ii) demonstrate how the summary indices may be used to compare different countries and to monitor within-country socioeconomic inequalities in health coverage; and (iii) to assess how summary indices may be affected by the choice of component indicators.

Methods

Data sources

The database used for the study11 is generated by the International Center for Equity in Health, Pelotas, Brazil. It includes all the demographic and health surveys (DHS; http://www.dhsprogram.com) and multiple indicator surveys (MICS; http://mics.unicef.org) carried out in low- and middle-income countries for which the data sets are publicly available. We used data from DHS phases 3 to 6 (since 1993) and MICS rounds III and IV (since 2005). More details of our approach to analysis of coverage is summarized elsewhere.9

Indicators

All indicators followed the definitions used by the Countdown to 2015 report.5 First we extracted the data required to calculate the two summary indices for each country. The composite coverage index is the weighted average of the percentage coverage of eight interventions along four stages of the continuum of care: reproductive care; maternal care; childhood immunization; and management of childhood illness. The interventions are: (i) family planning coverage (FPC);12 (ii) skilled birth attendant (SBA); (iii) at least one antenatal care visit by a skilled provider (ANC1); (iv) bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination; (v) three diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis (DTP3) vaccinations; (vi) measles (MSL) vaccination; (vii) oral rehydration therapy (ORT) for infant diarrhoea; and (viii) care-seeking for childhood pneumonia (CAREP). The index, CCI, is calculated according to the formula:

Each stage receives the same weight, and within each stage the indicators have equal weights, except for DTP3, which receives a weight of two because it requires more than one dose.

Co-coverage is calculated at the individual level as the total count of interventions received from the following eight: (i) at least one antenatal care visit; (ii) tetanus vaccination during pregnancy; (iii) skilled birth attendant; (iv) BCG vaccination; (v) DTP3 vaccination; (vi) measles vaccination; (vii) childhood vitamin A supplementation; and (viii) access to improved drinking water in the household. Therefore each mother–child pair receives a score that ranges from 0 to 8. All indicators were calculated for children aged 12–59 months, even when their standard definition was based on a different age range. For example, vaccination coverage is usually reported for children aged 12–23 months, but restricting the calculation of co-coverage to such a narrow age range would greatly reduce the sample size.10 We compared two arbitrary cut-off points: six or more interventions, to indicate mother–child pairs with high coverage; and fewer than three interventions, to indicate those whose coverage was lower.

Next, we extracted data on three health outcomes, chosen because they are stable and have good properties for monitoring health outcomes: (i) neonatal mortality rate; (ii) mortality rate in children younger than 5 years; and (iii) prevalence of stunting. We calculated these indicators from the same surveys used to estimate the composite coverage index and co-coverage.11 Neonatal and under-five mortality rates are the probability of a child born in a specified year dying before reaching the age of 30 days or 5 years respectively, if subject to current age-specific mortality rates, expressed per 1000 live births. The use of 30 instead of 28 days for neonatal mortality is related to the manner in which this indicator is calculated in demographic surveys.13 Due to sample size reasons, mortality rates were calculated on the basis of births that took place in the 5 years preceding the survey.13 The prevalence of stunting was defined as the proportion of children aged 0–59 months with height-for-age z-scores below −2 standard deviations of the World Health Organization child growth standards.14

Data analysis

There were three parts to the analysis. First, we used the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) to test the crude associations: (i) between the composite coverage index and co-coverage index; and (ii) between both summary indices and the three outcome indicators (neonatal and under-five mortality rates and prevalence of stunting). The correlations were also adjusted by the logarithm of each country’s per capita gross domestic product (GDP) obtained from the World Bank database.15

Second, we assessed family wealth in each survey using household asset indices derived through principal component analyses.16 To show whether each index was amenable to stratified analysis based on wealth, we selected nine countries (Benin, Cameroon, Congo, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Honduras, Jordan, Madagascar, Nigeria) with different magnitudes of inequalities for in-depth analyses. To do this we calculated the slope index of inequalities, which is a measure of absolute inequality expressed as the difference in coverage, in percentage points, between the richest and poorest households.17 We then divided the countries into tertiles of high, intermediate and low magnitude of inequalities and selected the three countries in the middle of the distribution in each tertile.

Third, we performed sensitivity analyses to correlate the composite coverage index and co-coverage index with two scores generated by principal component analysis. The first score included the eight variables used in the calculation of the composite coverage index, without the arbitrary weights. The second score included these eight variables plus data on another eight Countdown coverage indicators:11 (i) improved source of drinking water; (ii) houses with piped water connection; (iii) institutional delivery; (iv) postnatal care for mothers; (v) three doses of polio vaccine; (vi) oral rehydration therapy for diarrhoea; (vii) early initiation of breastfeeding; and (viii) improved sanitation facilities (not shared by other households). The purpose of these sensitivity analyses was to assess the robustness of the indices and whether the arbitrarily defined weights made a difference to the composite coverage index.

All analyses were carried out using Stata statistical software, version 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, United States of America).

Results

Data availability

In 189 DHS carried out since 1993, 41 surveys did not have information on vitamin A supplementation and eight surveys were missing data on oral rehydration therapy. In the 55 MICS, family planning coverage was not available in 34 surveys, vitamin A supplementation in 11 surveys and tetanus toxoid during pregnancy in four surveys. Data on all indictors were available for 134 DHS and only eight MICS. An additional difficulty with MICS was that some indicators were collected only for children younger than 24 months, whereas DHS covered all under-5-year-olds.

As co-coverage could not be calculated from MICS, we restricted the comparative analyses to 49 recent DHS (i.e. conducted after 2005) that included all the variables needed for both summary indices.

Summary index values

Table 1 presents the list of 49 countries studied and their respective summary indices. Composite coverage index values from DHS varied from 22.3% in Chad (in 2004) to 84.1% in Jordan (in 2012), with a median value of 66.8%. Co-coverage with 6+ interventions was lowest in Chad (10.5%) and highest in Maldives (91.3%), and the median was 58.2%. Co-coverage with < 3 interventions ranged from 61.2% in Chad to almost zero in Egypt, Honduras and Maldives, with a median value of 4.4%. The composite coverage index was strongly correlated with co-coverage of 6+ interventions (Pearson r = 0.73, P < 0.001) and with co-coverage of < 3 interventions (r = −0.84, P < 0.001).

Table 1. Comparison of the composite coverage and co-coverage indices showing estimated percentage coverage of maternal and child health interventions, and relative inequalities, in demographic and health surveys in 49 countries.

| Country, by WHO region | Survey year | Composite coverage indexa |

Co-coverage, 6+ interventionsb |

Co-coverage, < 3 interventionsb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated coverage, %c | Slope index of inequality, % pointsd | Estimated coverage, %c | Slope index of inequality, % pointsd | Estimated coverage, %c | Slope index of inequality, % pointsd | ||

| Africa | |||||||

| Benin | 2011 | 57.6 | 0.24 | 60.7 | 0.46 | 11.1 | −0.34 |

| Burkina Faso | 2010 | 64.6 | 0.31 | 69.8 | 0.39 | 5.1 | −0.14 |

| Burundi | 2010 | 66.8 | 0.12 | 65.2 | 0.18 | 0.9 | −0.01 |

| Cameroon | 2011 | 59.2 | 0.50 | 53.3 | 0.71 | 11.4 | −0.40 |

| Chad | 2004 | 22.3 | 0.42 | 10.5 | 0.35 | 61.2 | −0.62 |

| Comoros | 2012 | 62.1 | 0.26 | 47.6 | 0.27 | 10.6 | −0.11 |

| Republic of the Congo | 2011 | 72.8 | 0.23 | 67.4 | 0.52 | 4.4 | −0.20 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 2011 | 55.5 | 0.31 | 52.9 | 0.51 | 13.5 | −0.26 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2013 | 59.2 | 0.26 | 50.8 | 0.63 | 12.3 | −0.30 |

| Ethiopia | 2011 | 37.4 | 0.44 | 14.6 | 0.41 | 39.2 | −0.44 |

| Gabon | 2012 | 71.1 | 0.17 | 70.3 | 0.22 | 4.9 | −0.08 |

| Ghana | 2008 | 64.0 | 0.32 | 63.4 | 0.54 | 3.3 | −0.12 |

| Guinea | 2012 | 46.1 | 0.37 | 44.8 | 0.54 | 15.3 | −0.34 |

| Kenya | 2008 | 67.4 | 0.26 | 41.9 | 0.59 | 6.5 | −0.15 |

| Lesotho | 2009 | 71.5 | 0.25 | 58.2 | 0.57 | 4.9 | −0.16 |

| Liberia | 2013 | 61.4 | 0.20 | 62.7 | 0.60 | 6.9 | −0.29 |

| Madagascar | 2008 | 63.2 | 0.44 | 44.8 | 0.65 | 15.0 | −0.39 |

| Malawi | 2010 | 75.2 | 0.13 | 80.3 | 0.21 | 1.5 | −0.01 |

| Mali | 2012 | 49.4 | 0.39 | 45.0 | 0.64 | 19.4 | −0.40 |

| Mozambique | 2011 | 60.2 | 0.36 | 56.1 | 0.65 | 9.1 | −0.24 |

| Namibia | 2006 | 76.7 | 0.30 | 65.7 | 0.39 | 3.9 | −0.12 |

| Niger | 2012 | 56.3 | 0.31 | 37.6 | 0.54 | 16.4 | −0.29 |

| Nigeria | 2013 | 43.3 | 0.70 | 30.9 | 0.82 | 43.7 | −0.87 |

| Rwanda | 2010 | 72.9 | 0.13 | 74.7 | 0.24 | 0.5 | −0.01 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 2008 | 74.7 | 0.09 | 72.1 | 0.25 | 2.5 | −0.02 |

| Senegal | 2012 | 62.2 | 0.19 | 64.9 | 0.60 | 3.3 | −0.18 |

| Sierra Leone | 2013 | 66.8 | 0.12 | 62.9 | 0.37 | 4.4 | −0.05 |

| Swaziland | 2006 | 75.3 | 0.15 | 77.4 | 0.37 | 1.4 | −0.05 |

| Uganda | 2011 | 65.0 | 0.20 | 52.1 | 0.26 | 5.1 | −0.03 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 2010 | 70.0 | 0.29 | 50.5 | 0.55 | 5.5 | −0.10 |

| Zambia | 2007 | 69.3 | 0.21 | 38.1 | 0.57 | 7.1 | −0.10 |

| Zimbabwe | 2010 | 70.5 | 0.14 | 61.3 | 0.42 | 6.9 | −0.13 |

| Americas | |||||||

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | 2008 | 71.3 | 0.25 | 54.6 | 0.62 | 3.4 | −0.10 |

| Dominican Republic | 2007 | 81.5 | 0.07 | 73.5 | 0.28 | 1.4 | −0.04 |

| Haiti | 2012 | 57.6 | 0.23 | 37.5 | 0.34 | 12.7 | −0.18 |

| Honduras | 2011 | 83.7 | 0.09 | 81.1 | 0.39 | 0.3 | −0.01 |

| Nicaragua | 2001 | 77.8 | 0.21 | 71.6 | 0.54 | 3.3 | −0.14 |

| Peru | 2012 | 83.9 | 0.13 | 63.2 | 0.44 | 2.1 | −0.09 |

| South-East Asia | |||||||

| Bangladesh | 2011 | 68.4 | 0.25 | 55.0 | 0.52 | 3.2 | −0.09 |

| India | 2005 | 64.0 | 0.41 | 41.3 | 0.66 | 20.6 | −0.48 |

| Indonesia | 2012 | 80.4 | 0.17 | 60.8 | 0.37 | 7.8 | −0.25 |

| Maldives | 2009 | 79.9 | −0.06 | 91.3 | 0.06 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Nepal | 2011 | 63.6 | 0.35 | 66.5 | 0.64 | 3.8 | −0.14 |

| Timor-Leste | 2009 | 59.2 | 0.29 | 44.2 | 0.51 | 20.9 | −0.39 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | |||||||

| Egypt | 2008 | 77.3 | 0.16 | 69.5 | 0.55 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| Jordan | 2012 | 84.1 | 0.03 | 38.6 | −0.18 | 0.4 | 0.00 |

| Morocco | 2003 | 72.3 | 0.31 | 42.3 | 0.76 | 4.5 | −0.16 |

| Pakistan | 2012 | 64.3 | 0.40 | 46.2 | 0.73 | 16.4 | −0.47 |

| Western Pacific | |||||||

| Philippines | 2013 | 76.9 | 0.18 | 79.7 | 0.46 | 3.4 | −0.19 |

WHO: World Health Organization.

Note: Population denominators are different for each intervention within the composite coverage index and co-coverage index.8,10

a The composite coverage index is a weighted average of the coverage of eight interventions: family planning coverage; antenatal care; skilled birth attendant; bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination; three doses of diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis (DTP3) vaccination; measles vaccination; oral rehydration therapy for infant diarrhoea; and care-seeking for childhood pneumonia.

b The co-coverage index is calculated at the individual level from the total number received from the following eight interventions: at least one antenatal care visit; tetanus vaccination during pregnancy; skilled birth attendant; BCG vaccination; DTP3 vaccination; measles vaccination; childhood vitamin A supplementation; and access to improved drinking water in the household.

c Estimated coverage is the weighted average percentage coverage of the interventions (composite coverage index), or the percentage coverage of children aged 12–59 months who received six or more or less than three interventions (co-coverage index).

d Slope index of inequality is calculated through a logistic regression model that takes the natural logarithm of the odds of the dependent variable to create a continuous criterion on which linear regression is conducted. This approach allows the calculation of the difference in percentage points between the fitted values of the health indicator for the top and the bottom of the wealth distribution.9,17

Source: Data for all indicators were extracted from demographic and health surveys, available at http://www.dhsprogram.com.

Correlations with outcomes

The crude correlations between the composite coverage index and neonatal mortality rate, under-five mortality rate and stunting prevalence were r = −0.57, −0.68 and −0.46, respectively. For co-coverage with 6+ interventions, the corresponding crude coefficients were weaker: r −0.49, −0.43 and −0.33, respectively. Adjusting these correlations for log GDP per capita did not make any appreciable change to the reported correlations (Table 2).

Table 2. Crude and adjusted correlations between the composite coverage and co-coverage indices and three health outcome indicators, in demographic and health surveys in 49 countriesa .

| Outcome indicatorsb | Composite coverage indexc |

Co-coverage, 6+ interventionsd |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude r | P | GDP-adjusted r | P | Crude r | P | GDP-adjusted r | P | |||

| Neonatal mortality rate | −0.57 | < 0.001 | −0.69 | < 0.001 | −0.49 | < 0.001 | −0.48 | 0.001 | ||

| Under-five mortality rate | −0.68 | < 0.001 | −0.75 | < 0.001 | −0.43 | 0.002 | −0.48 | 0.003 | ||

| Stunting prevalence | −0.46 | 0.001 | −0.45 | 0.003 | −0.33 | 0.023 | −0.32 | 0.041 | ||

GDP: gross domestic product.

Note: Cells show Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and their associated P-values. Correlations were adjusted for GDP of each country.

a Countries were: World Health Organization (WHO) African Region: Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Swaziland, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe; WHO Region of the Americas: the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Peru; WHO South-East Asia Region: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Nepal, Timor-Leste; WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region: Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Pakistan; and WHO Western Pacific Region: Philippines.

b Neonatal mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specified year dying before reaching the age of 30 days per 1000 live births. Under-five mortality rate is the probability of a child born in a specified year dying before reaching the age of 5 years per 1000 live births. Stunting prevalence is the percentage of children aged 0–59 months with height-for-age z-scores below −2 standard deviations of the WHO child growth standard.

c The composite coverage index is a weighted average of the coverage of eight interventions: family planning coverage; antenatal care; skilled birth attendant; bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination; three doses of diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis (DTP3) vaccination; measles vaccination; oral rehydration therapy for infant diarrhoea; and care-seeking for childhood pneumonia.

d The co-coverage index is calculated at the individual level from the total number received from the following eight interventions: at least one antenatal care visit; tetanus vaccination during pregnancy; skilled birth attendant; BCG vaccination; DTP3 vaccination; measles vaccination; childhood vitamin A supplementation; and access to improved drinking water in the household.

Source: Data for all indicators were extracted from demographic and health surveys, available from http://www.dhsprogram.com.

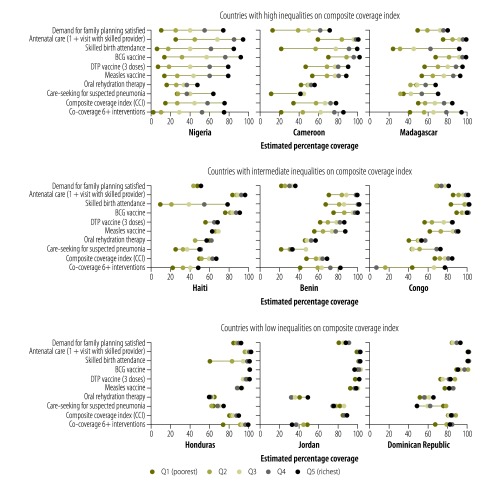

Inequalities in coverage

Fig. 1 shows a series of equiplots in which the two summary indices and coverage levels of the eight additional Countdown indicators are presented by wealth quintiles of the populations for the nine selected countries. In the equiplots, the poorest and richest quintiles are shown connected by a horizontal line. When one of the circles is outside this line (e.g. co-coverage with 6+ interventions in Congo, or oral rehydration therapy in Haiti), this indicates that the inequality pattern is not stepwise and monotonic. Fig. 1 shows that by summarizing the information from several different coverage indicators the composite coverage index and co-coverage provide useful summaries of the degrees of inequality of coverage in each country. Inequalities according to co-coverage with 6+ interventions were wider than those for the composite coverage index in most countries.

Fig. 1.

Equiplots of percentage coverage of maternal and child health interventions for the composite coverage and co-coverage indices by wealth quintile, in nine countries with different levels of inequality

BCG: bacille Calmette–Guérin; DTP: diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis.

Notes: The wealth index is derived through principal component analysis and was divided into quintiles. The composite coverage index is a weighted average of the coverage of eight interventions: family planning coverage; antenatal care; skilled birth attendant; BCG vaccination; DTP3 vaccination; measles vaccination; oral rehydration therapy for infant diarrhoea; and care-seeking for childhood pneumonia. The co-coverage index is calculated at the individual level as the total number received from the following eight interventions: at least one antenatal care visit; tetanus vaccination during pregnancy; skilled birth attendant; BCG vaccination; DTP3 vaccination; measles vaccination; childhood vitamin A supplementation; and access to improved drinking water in the household.

Source: Data for all indicators were extracted from demographic and health surveys, available at http://www.dhsprogram.com.

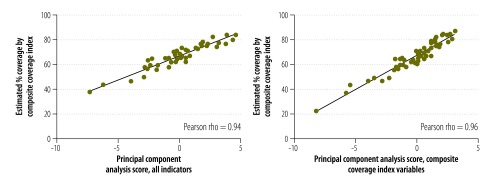

Choice of indicators

The composite coverage index was strongly associated with the first factor derived through principal component analysis from the 16 intervention coverage measures listed in the Methods section (r = 0.94, P < 0.001). When principal component analysis was restricted to the eight indicators included in the composite coverage index, the correlation was stronger (r = 0.96, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of percentage coverage of maternal and child health interventions for the composite coverage index versus two summary indices derived through principal component analyses

Note: The composite coverage index is a weighted average of the coverage of eight interventions: family planning coverage; antenatal care; skilled birth attendant; bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination; three doses of diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis vaccination; measles vaccination; oral rehydration therapy for infant diarrhoea; and care-seeking for childhood pneumonia.

Source: Data for all indicators were extracted from demographic and health surveys, available at http://www.dhsprogram.com.

Discussion

The composite coverage and co-coverage indices represent two approaches to obtaining a summary measure of intervention coverage, with important differences (Table 3). The composite coverage index is a weighted average of standard indicators whereas co-coverage is a count of interventions received, often expressed as the percentage above or below a certain count. Both are easy to interpret and amenable to graphic displays. Unlike co-coverage, the composite coverage index is simple to calculate and does not require reanalyses of individual survey data.

Table 3. Comparison of the two summary indices of coverage of maternal and child health interventions according to selected criteria.

| Issue | Composite coverage indexa | Co-coverageb |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical aspects | ||

| Level of analysis | Group | Individual (child–mother) |

| Estimation of variance | Complex, requires re-sampling techniques | Simple |

| Missing indicators | Most surveys include all required indicators | Many surveys are missing indicators, especially vitamin A supplementation and tetanus toxoid vaccine |

| Indicator definitions | Indicators are based on standard international definitions | Indicators refer to children aged 12–59 months. Involves reanalysis of surveys |

| Weighting | Weighted by stage of the continuum of care | Unweighted |

| Small sample sizes | Mostly affects immunization and case management indicators for which the denominators include a fraction of all children | Because indicators are calculated for children aged 12 months or older, small samples are available for surveys where some variables (e.g. antenatal and delivery care) are only collected for those born in the past 24 months |

| Monitoring | ||

| Types of intervention | Preventive and curative interventions | Limited to preventive interventions |

| Conceptual model | Based on the continuum of care | No conceptual model |

| Target groups for interventions | Curative interventions apply only to children who are ill | All interventions are targeted to all mothers and children |

| Vaccines | Represent 25% of the index | Represent 50% of the index |

| Advocacy | ||

| Human rights’ assessment | At group level | At individual level |

| Identification of who is not receiving interventions | Only groups of mothers and children may be identified | Individual mothers and children may be identified |

a The composite coverage index is a weighted average of the coverage of eight interventions: family planning coverage; antenatal care; skilled birth attendant; bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination; three doses of diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis (DTP3) vaccination; measles vaccination; oral rehydration therapy for infant diarrhoea; and care-seeking for childhood pneumonia.

b The co-coverage index is calculated at the individual level from the total number received from the following eight interventions: at least one antenatal care visit; tetanus vaccination during pregnancy; skilled birth attendant; BCG vaccination; DTP3 vaccination; measles vaccination; childhood vitamin A supplementation; and access to improved drinking water in the household.

We found that the two indices were strongly correlated, which is not surprising because they have five interventions in common: antenatal care, skilled birth attendant and the three childhood vaccinations (BCG, DTP and measles). However, their interpretation and primary uses are rather different. The composite coverage index combines preventive and curative interventions along the continuum of care. Being an average, it is less sensitive to low precision of each component, making it suitable for analyses of subgroups (e.g. geographical regions or wealth quintiles). On the other hand, as an average it will be more equitably distributed than some of its component interventions (e.g. skilled birth attendance, in many countries) and less equitably distributed than others (e.g. immunization indicators).

Conceptually, the two indicators are also different (Table 3). The composite coverage index is estimated at the group level, as the average coverage of eight indicators that are available in most surveys. However, sample sizes can be a limitation for indicators on case management of illnesses, particularly in smaller surveys. In contrast, co-coverage is a cumulative measure estimated at the individual mother and child level. All of its component indicators must refer to the same age range, i.e. children 12–59 months of age; infants are excluded because they are not old enough to have received the vaccines included in the index. Because it includes interventions that are not prioritized in all countries (e.g. childhood vitamin A supplementation) the number of interventions available may vary from country to country, a fact that hinders cross-country comparisons. To minimize this problem, the present analyses were restricted to surveys reporting on the interventions included in both summary indices.

The concept of co-coverage is directly relevant to human rights issues. For example, in the 2013 Nigeria DHS, 13% of mothers and children failed to receive any of the eight interventions included in the co-coverage index, of whom 64% belonged to families in the poorest quintile.18 This type of information has clear relevance for advocacy and efforts to help all children to receive the essential interventions they need.

The sensitivity analysis comparing the composite coverage index with two indices derived from the first component of principal component analyses showed very high correlations. In one case, we used 16 different indicators,18 and found that including them did not substantially change the composite coverage index. In the second case, using the same eight composite coverage index indicators but with principal components analysis, we found that the arbitrary weights did not make a difference. The inclusion of other interventions, e.g. insecticide treated bed nets, may be desirable but would restrict the index to countries where malaria is endemic.

The composite coverage index correlated more strongly with mortality and malnutrition than did co-coverage. Mortality indicators are calculated retrospectively based on live births in the five years before the survey, whereas information on coverage refers to time periods closer to the date of the interview. Nevertheless, mortality rates are unlikely to change rapidly, and so the correlations are likely to be valid. The high correlations and the simplicity of calculation makes the composite coverage index a useful tool for monitoring country progress towards universal reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health coverage. Using a single index to benchmark coverage, assess time trends, compare countries and document inequalities is a definite advantage of this index.

There is rising interest in documenting subnational geographical disparities in health care coverage.19,20 Policy-makers often complain that traditional equity analyses fail to pinpoint specific areas in a country at highest need. The co-coverage indicator combined with spatial analysis can be used to target interventions to small geographical zones.21

These indicators have limitations. It is difficult to calculate the standard error of the composite coverage index because the coverages of the component indicators are highly correlated. Re-sampling methods are required and, given that cluster samples are used in the surveys, it is necessary to estimate all components of the composite coverage index, excluding one cluster at a time. Especially in large surveys, this can consume many computer hours. In contrast, calculation of standard errors for co-coverage is straightforward. The disadvantage of the co-coverage index, however, is that the data to calculate it are missing from some surveys. Interventions are restricted to those needed by all mothers and children. In addition, several MICS only provide information on variables such as antenatal or delivery care for births in the two years before the survey, thus restricting the age range of children that can be studied and compromising the sample sizes.

As new interventions are introduced and scaled up, information on their coverage becomes available. Examples include postnatal care for the mother and for the child, and new vaccines against rotavirus and pneumococcal infection. Other interventions may also change. For example, oral rehydration therapy – defined as increased fluids plus continued feeding – is being replaced with treatment with oral rehydration solution4 plus zinc.5 In 2015, oral rehydration solution plus zinc was available for 37 of the 75 Countdown countries, with a median coverage of only 1%. In the Countdown analysis, to track time trends we decided to retain the oral rehydration solution indicator in the definition of the composite coverage index, but for the SDGs we already have a baseline indicator for oral rehydration solution plus zinc. The composite coverage index indicator may therefore be reformulated. In the progress towards universal health coverage it is likely that the same dilemma will be faced between ensuring consistency and continuity of data collection, and incorporating new interventions in summary indices.

Work on how to monitor coverage in the context of universal health coverage is already under way. It has been proposed that a set of tracer coverage indicators can be selected, divided into two groups – promotion and prevention; and treatment and care – and that averages of several tracer indicators should be calculated, using an approach that is similar to the composite coverage index.22 Monitoring universal health coverage is more complex than monitoring only coverage of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health care; indicators also need to cover cardiovascular disease, mental health, injuries, cancer and several infectious diseases, as well as financial protection.23,24 Given that universal health coverage tracer indicators tend to be age-specific, and in some cases sex-specific, it is unlikely that a cumulative index such as co-coverage will be useful as a single summary measure. Thus, the approach of using averages – as in the composite coverage index – is more appropriate for monitoring universal health coverage.

The universal health coverage measurement exercises mentioned above22–24 all stress the lack of timely, population-based and regular information for monitoring coverage. The availability of data on reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health is greater than for other age ranges, particularly due to the increase in DHS and MICS during the MDG era. Nevertheless, there are still several countries without any recent surveys and other countries with few data points over time. Even when surveys are available, essential variables may not be collected.5

Our experience with summary indices has shown that several issues related to definition and data availability must be addressed. We believe, however, that their greater stability and precision represent a substantial advantage compared with monitoring a large number of separate indicators. Average coverage indices such as the composite coverage index will continue to play a role for global, national and subnational monitoring and accountability, and cumulative co-coverage indices will be important for advocacy and human rights purposes.

Funding:

This paper was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number: 101815/Z/13/Z); the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number: OPP1135522); and the Associação Brasileira de Saúde Coletiva (ABRASCO).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Millennium development goals [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2016. Available from: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/http://[cited 2016 Feb 2].

- 2.Victora CG, Requejo JH, Barros AJ, Berman P, Bhutta Z, Boerma T, et al. Countdown to 2015: a decade of tracking progress for maternal, newborn, and child survival. Lancet. 2016 May 14;387(10032):2049–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00519-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sustainable Development Goals [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2016. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabledevelopmentgoals [cited 2016 Feb 2].

- 4.Bryce J, Arnold F, Blanc A, Hancioglu A, Newby H, Requejo J, et al. CHERG Working Group on Improving Coverage Measurement Measuring coverage in MNCH: new findings, new strategies, and recommendations for action. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Countdown to 2015. A decade of tracking progress for maternal newborn and child survival: the 2015 report. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2015. Available from: http://www.countdown2015mnch.org/documents/2015Report/Countdown_to_2015_final_report.pdf [cited 2016 Feb]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Countdown to 2015. Tracking progress in child survival: the 2005 report. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grove J, Claeson M, Bryce J, Amouzou A, Boerma T, Waiswa P, et al. Kirkland Group Maternal, newborn, and child health and the Sustainable Development Goals – a call for sustained and improved measurement. Lancet. 2015 Oct 17;386(10003):1511–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00517-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boerma JT, Bryce J, Kinfu Y, Axelson H, Victora CG, Victora CG, Countdown 2008 Equity Analysis Group Mind the gap: equity and trends in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health services in 54 Countdown countries. Lancet. 2008 Apr 12;371(9620):1259–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barros AJ, Victora CG. Measuring coverage in MNCH: determining and interpreting inequalities in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health interventions. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Victora CG, Fenn B, Bryce J, Kirkwood BR. Co-coverage of preventive interventions and implications for child-survival strategies: evidence from national surveys. Lancet. 2005 Oct 22-28;366(9495):1460–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67599-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Database for national surveys on maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries [Internet]. Pelotas: International Centre for Equity in Health; 2016. Available from: http://www.equidade.org [cited 2016 Feb].

- 12.Barros AJ, Boerma T, Hosseinpoor AR, Restrepo-Mendez MC, Wong KL, Victora CG. Estimating family planning coverage from contraceptive prevalence using national household surveys. Glob Health Action. 2015 Nov 9;8:29735. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.29735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutstein SO, Rojas G.Guide to demographic and health surveys statistics: the demographic and health survey methodology. Calverton: United States Agency for International Development; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The WHO child growth standards [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en/http://[cited 2016 Feb 2].

- 15.GDP per capita indicator. Washington: World Bank; 2016. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CDhttp://[cited 2016 Feb 2].

- 16.Demographic and health surveys: wealth index construction. New York: United States Agency for International Development; 2016. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/topics/wealth-index/Wealth-Index-Construction.cfmhttp://[cited 2016 Feb 2].

- 17.Regidor E. Measures of health inequalities: part 2. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004 Nov;58(11):900–3. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Victora C, Somers K. Equity: a platform for achieving the SDGs and promoting human rights [Internet]. Washington: Devex; 2015. Available from: https://www.devex.com/news/equity-a-platform-for-achieving-the-sdgs-and-promoting-human-rights-87478 [cited 2016 Feb 2]. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Barros AJ, Wong KLM, Boerma T, Victora CG. Monitoring subnational regional inequalities in health: measurement approaches and challenges. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0307-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumalija CJ, Perera S, Masanja H, Rubona J, Ipuge Y, Mboera L, et al. Regional differences in intervention coverage and health system strength in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alegana VA, Wright JA, Pentrina U, Noor AM, Snow RW, Atkinson PM. Spatial modelling of healthcare utilisation for treatment of fever in Namibia. Int J Health Geogr. 2012;11(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-11-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boerma T, AbouZahr C, Evans D, Evans T. Monitoring intervention coverage in the context of universal health coverage. PLoS Med. 2014 Sep;11(9):e1001728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagstaff A, Cotlear D, Eozenou PH-V, Buisman LR. Measuring progress towards universal health coverage: with an application to 24 developing countries [policy research working paper; no. WPS 7470]. Washington: World Bank; 2015. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/917441468180851481/pdf/WPS7470.pdf [cited 2016 Feb 2].

- 24.Wagstaff A, Dmytraczenko T, Almeida G, Buisman L, Hoang-Vu Eozenou P, Bredenkamp C, et al. Assessing Latin America’s progress toward achieving universal health coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015 Oct;34(10):1704–12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

In 189 DHS carried out since 1993, 41 surveys did not have information on vitamin A supplementation and eight surveys were missing data on oral rehydration therapy. In the 55 MICS, family planning coverage was not available in 34 surveys, vitamin A supplementation in 11 surveys and tetanus toxoid during pregnancy in four surveys. Data on all indictors were available for 134 DHS and only eight MICS. An additional difficulty with MICS was that some indicators were collected only for children younger than 24 months, whereas DHS covered all under-5-year-olds.

As co-coverage could not be calculated from MICS, we restricted the comparative analyses to 49 recent DHS (i.e. conducted after 2005) that included all the variables needed for both summary indices.