Abstract

Objectives

To assess ECG changes in patients with tramadol-induced seizure(s) and compare these changes in lower and higher than 500 mg tramadol doses as a main goal.

Material and methods

In an analytical-cross sectional manner over 1 year, 170 patients with idiosyncratic seizure(s) after using tramadol, were studied. Full data were recorded for each patient. ECGs were taken from all the patients on admission and 1 h later and were assessed for findings.

Results

70 of 170 patients (41.2%) had used lower than 500 mg doses of tramadol while 90 patients (52.9%) were included in the high dose group. Rate of female patients in the high dose group was significantly higher. The average age of patients in the high dose group was significantly lower (22.04 vs 25.76). The high dose group had significantly higher heart rates. There was no history of cardiovascular diseases; two patients had previous history of seizure. No significant difference was shown between low dose and high dose groups from the point of ECG changes.

Discussion and conclusion

Using doses higher than 500 mg is more frequently seen in women, young people and those who have not experienced previous use of tramadol. Terminal S wave, sinus tachycardia, and terminal R wave in the lead aVR are among the most common ECG changes in tramadol users.

Keywords: ECG changes, Tramadol, Seizure

1. Introduction

Tramadol is a synthetic analog of codeine1 with a 10-fold weaker affinity for opium receptors (resulting in analgesic effects) compared to morphine.2 It is absorbed rapidly and almost completely, following oral intake.3 There are also, slow-releasing forms of tramadol in which the free portion is being released within 12 h and the highest concentration is being achieved within 4.9 h.4 20% of tramadol gets bound to plasma proteins.5 Tramadol is distributed in blood, kidney, and brain, but it cannot be found in muscles. Like morphine, tramadol is significantly accumulated in bile rather than in kidneys and liver and its clearance takes 6 h.4 First, tramadol was claimed to be a safe agent with a low potential for being abused,6 but later, adverse reactions were reported. Its complications are inappropriately higher in overdose. Published cases of overdoses are mainly in an acute, oral, and intentional setting. Majority of cases become symptomatic within the first 4 h and the symptoms disappear after 24 h. It is reported that up to 20% of cases need intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Tramadol overdose generally involves young people in third decade of their lives, on average.7 Central nervous system complications are the most frequently reported manifestations ranging from agitation to deep coma.5 Seizure has been considered to have an important role in tramadol toxicity as declared by studies and the literature.5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Nausea/vomiting and respiratory depression have also been reported.5, 7, 8 Of cardiac issues, hypotension, especially affecting systolic blood pressure (SBP) and sinus tachycardia have been listed as tramadol toxicity complications.5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14

Management of tramadol toxicity is focused on supportive care, including oxygen, fluid therapy, and diazepam for controlling agitation or seizure.

Few studies have been conducted to investigate electrocardiographic (ECG) changes after idiosyncratic seizures following tramadol use. Our study was performed to evaluate ECG changes in this category of patients.

2. Material and methods

This study was conducted in an analytical cross sectional manner since January 2013 to January 2014. The study was approved by ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS) and all ethical issues regarding research were fulfilled during the study. Informed consent was taken from each patient or his/her companion(s). 170 patients, admitted to a teaching Hospital because of an idiosyncratic seizure after using tramadol, were included in the study. Inclusion criteria were age between 16 and 80 years, complaints following tramadol abuse. Exclusion criteria included cardiovascular disease, proof of other drugs and substances abuse with tests and use of drugs affecting cardiovascular system before admission. A checklist including age, sex, frequency of seizures during admission, history of seizure, and dose and duration of tramadol use was filled. ECG was taken from all the patients 1 h after admission. QT interval prolongation, QRS widening, terminal S wave in the lead D1, terminal R wave in the lead aVR, and sinus tachycardia were assessed in ECGs by trained emergency room physician. The group of patients who had used doses lower than 500 mg of tramadol, was named “low dose” group and patients who had used doses higher than 500 mg, were included in the so-named “high dose” group.15, 16, 17 Acquired data were analyzed in SPSS V.16 with independent sample t-test for quantitative and chi-square test for qualitative comparison.

3. Results

170 patients were included in the study; In low dose group there were 70 (41.2%) patients, including 68 men and 2 women, while 90 (52.9%) of patients, including 76 men, 13 women and unknown sex of one patient, entered the high dose group. Dose of tramadol used, has not been recorded for 10 patients (5.9%).

There was no difference in respiratory rates (RRs) between two groups but a significant difference between pulse rates (PRs) of two groups has been observed. PRs were lower in the high dose group compared to the low dose group (92.94 ± 17.80 vs. 101.06 ± 20.03; p = 0.009) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic patients' characteristics.

| Low dose group | High dose group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 25.76 ± 7.30 | 22.04 ± 6.21 | 0.001 |

| Gender | 68 males (97.14%), 2 females (2.85%) | 76 males (85.39%), 13 females (14.60%) | 0.012 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 124 ± 14.25 | 120.90 ± 15.17 | 0.190 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 77.94 ± 8.20 | 75.40 ± 10.55 | 0.103 |

| Respiratory rate (RR) | 23.31 ± 2.61 | 22.76 ± 2.61 | 0.106 |

| Pulse rate (PR) | 101.06 ± 20.03 | 92.94 ± 17.80 | 0.009 |

There was not even one positive history of heart disease in the participants. 157 patients denied any history of cardiac problems and in 13 patients there was no recorded document supporting their cardiac history. Two cases had a positive previous history of seizure; one of them was due to previous use of tramadol.

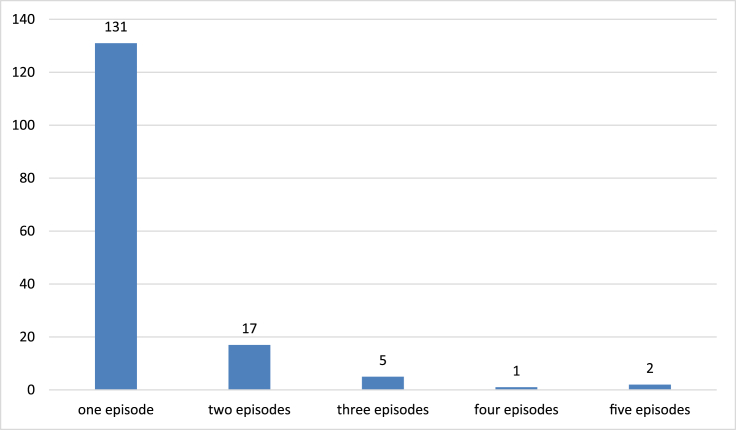

Number of seizure attacks was 1.18 ± 0.615 and 1.26 ± 0.604 in the low and high dose groups, respectively (p = 0.169). Fig. 1 shows the frequency of seizure attacks in patients after tramadol use.

Fig. 1.

Number of seizure episodes in the individuals.

The time interval between using tramadol and occurrence of seizure(s) was measured in both groups. It was 150 min in the low dose group, compared to 235 min in the high dose group; there was no statistically significant difference between two groups (p = 0.113).

The positive history of previous tramadol use was significantly more frequent in the low dose group (p = 0.002), as 47 of patients reported previous use of tramadol, while 21 of them denied any history of previous use (compared to 38 and 48 patients, respectively, in the high dose group).

Overall, 68 patients (42.5%) showed sinus tachycardia and 4 patients (2.4%) had sinus bradycardia; sinus tachycardia was significantly much more frequent in the high dose group (47 vs. 21 patients; p = 0.005).

There was no statistically meaningful difference between two groups from the point of bradycardia (3 patients in the high dose group vs. just 1 patient in the low dose group; p = 0.632).

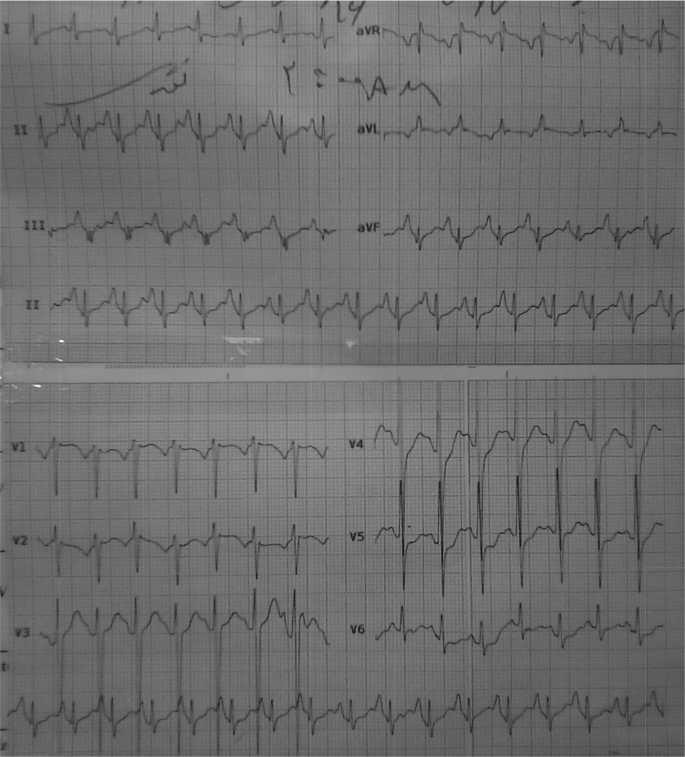

The most frequent ECG changes were terminal S wave, sinus tachycardia, terminal R wave in the lead aVR, T wave inversion, right bundle branch block (RBBB), and QRS widening, respectively. No left bundle branch block (LBBB), QT interval prolongation (Fig. 2), second or third degree atrio-ventricular (AV) block were seen. Table 2 demonstrates ECG changes in details.

Fig. 2.

One of patients ECG demonstrating sinus tachycardia and QT prolongation (Corrected QT is about 0.50 msec).

Table 2.

ECG changes in the patients.

| ECG changes | Low dose groups | High dose group | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal S | Present | 53 | 61 | 114 | 0.271 |

| Absent | 17 | 29 | 46 | ||

| Terminal R in aVR | Present | 19 | 36 | 55 | 0.089 |

| Absent | 51 | 54 | 105 | ||

| ST depression | Present | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.799 |

| Absent | 68 | 88 | 156 | ||

| T inversion | Present | 6 | 14 | 20 | 0.185 |

| Absent | 64 | 76 | 140 | ||

| RBBB | Present | 5 | 12 | 17 | 0.207 |

| Absent | 65 | 78 | 143 | ||

| QRS widening | Present | 5 | 6 | 11 | 0.906 |

| Absent | 65 | 84 | 149 | ||

| AV Block Type I | Present | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.376 |

| Absent | 70 | 89 | 159 | ||

| Sinus Tachycardia | Present | 21 | 47 | 68 | 0.005 |

| Absent | 49 | 43 | 92 | ||

| Sinus Bradycardia | Present | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.632 |

| Absent | 69 | 88 | 157 | ||

ECG: electrocardiography, RBBB: right bundle branch block, AV: atrio-ventricular.

4. Discussion

Seizure is a critical issue in tramadol toxicity. While population-based reports speculate the frequency of seizure from 8 to 14%,5, 7 hospital reports declare a higher risk for seizure, from 15 to 35%.8, 9 It is seen that tramadol leads to seizure if it's used in doses higher than therapeutic ranges or in combination with antidepressants10; it has not been reported after standard and appropriate doses. More than half of tramadol abusers (54%) have experienced at least one episode of tonic-clonic seizure in a 3-year follow-up period.11 Different amounts have been mentioned in various studies as the minimum dose of tramadol needed to cause seizure, ranges from 200 mg7–350 mg8 and even higher. In our study, 9 patients had used 100 mg of tramadol and it was the least dose used by our cases.

The average age of people experiencing tramadol overdose, is around 30 years according to different studies, which is consistent with our findings. The average age of patients was 23.69 years in our study. Different studies have reported the average interval of seizure occurrence after using tramadol to be 4 h which was almost the same (3.26 h) in our study.5, 18

In our study which was done among patients with tramadol toxicity and seizure, number of men was significantly higher than the women, but association of women with doses higher than 500 mg was stronger. Maybe the reason is that men usually abuse Tramadol as substance but women abuse it to commit suicide. It has been reported in previous studies that tramadol toxicity in non-hospital setting is a little bit higher in women than men, but it's not true for in-hospital setting.8, 9

Hypotension, especially affecting SBP and sinus tachycardia are the cardiac complications5, 7 resembling findings caused by other opioids. In majority of toxicities, no arrhythmia was reported except to tachycardia.8 There are a few case reports of Brugada ECG pattern, right-sided heart failure (HF), refractory shock, and asystole.12, 13, 14 Interestingly, hypertension is seen in some cases.5 As said before, higher HRs and sinus tachycardia were seen in high dose group and no hypotension or any considerable ECG changes or arrhythmias were found. One study showed an association between seizure and male gender, chronic use, intentional use, and tachycardia,18 but other studies didn't support it. In one recent study, the most common types of ECG changes were sinus tachycardia, a deep S wave in leads I and aVL, right axis deviation, and long QTc interval, respectively. Brugada pattern and sinus bradycardia were rarely presented.19 As in our study, most of studies have not reported any arrhythmia beyond tachycardia or any serious cardiovascular toxicity. Overall, abnormal R or S waves were not seen in the aVR. There are just one or two case reports of serious abnormalities like Brugada pattern, acute right-sided HF, refractory shock, and asystole. We didn't observe any case of hypertension, although it was reported in some studies.

We showed people who have not used tramadol before, are more likely to use higher doses in cases of overdose in comparison to those who have experienced it, before; this could be due to the cautions taken by experienced users of tramadol.

5. Limitations

We faced some limitations in our study including the unknown dose of tramadol used in some patients, inability to follow-up the patients who were transferred to ICU or left the hospital, incomplete data in some patients, and unawareness of concomitant drugs used in some cases.

6. Conclusion

Using doses higher than 500 mg was seen significantly more frequent in women, young people, and those who had not previously used tramadol. Terminal S wave, sinus tachycardia, and terminal R wave in the lead aVR are among the most common ECG changes seen in tramadol users. It is important to consider abovementioned findings in addition to drug history in the young patients who are admitted with seizure(s) following tramadol use.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey.

Contributor Information

Peyman Hafezi Moghadam, Email: hafezimoghadam@yahoo.com.

Najmeh Zarei, Email: znajme@gmail.com.

Davood Farsi, Email: davoodfa2004@yahoo.com.

Saeed Abbasi, Email: saieedabbasi@yahoo.com.

Mani Mofidi, Email: manimofidi@yahoo.com.

Mahdi Rezai, Email: mah_re@yahoo.com.

Babak Mahshidfar, Email: bmahshidfar@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kovelowski C.J., Raffa R.B., Porreca F. Tramadol and its enantiomers differentially suppress c-fos-like immunoreactivity in rat brain and spinal cord following acute noxious stimulus. Eur J Pain. 1998;2:211–219. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3801(98)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sansone R.A., Sansone L.A. Tramadol: seizures, serotonin syndrome, and coadministered antidepressants. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2009;6:17–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grond S., Sablotzki A. Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:879–923. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klingmann A., Skopp G., Pedal I. Distribution of morphine and morphine glucuronides in body tissue and fluids— postmortem findings in brief survival. Arch Kriminol. 2000;206:38–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiller H.A., Gorman S.E., Villalobos D. Prospective multicenter evaluation of tramadol exposure. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35:361–364. doi: 10.3109/15563659709043367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore P.A. Pain management in dental practice: tramadol vs. codeine combinations. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:1075–1079. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marquardt K.A., Alsop J.A., Albertson T.E. Tramadol exposures reported to statewide poison control system. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1039–1044. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tashakori A., Afshari R. Tramadol overdose as a cause of serotonin syndrome: a case series. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010;48:337–341. doi: 10.3109/15563651003709427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shadnia S., Soltaninejad K., Heydari K. Tramadol intoxication: a review of 114 cases. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27:201–205. doi: 10.1177/0960327108090270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ripple M.G., Pestaner J.P., Levine B.S., Smialek J.E. Lethal combination of tramadol and multiple drugs affecting serotonin. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2000;21:370–374. doi: 10.1097/00000433-200012000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jovanovic-Cupic V., Marinovic Z., Nesic N. Seizures associated with intoxication and abuse of tramadol. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44:143–146. doi: 10.1080/1556365050014418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daubin C., Quentin C., Goullé J.P. Refractory shock and asystole related to tramadol overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45:961–964. doi: 10.1080/15563650701438847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afshari R., Tashakori A., Shakiba A.H. Tramadol overdose induced CPK rise, haemodynamic, and electrocardiographic changes, and seizure. Clin Toxicol. 2008;46(5):369. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole J.B., Sattiraju S., Bilden E.F. Isolated tramadol overdose associated with Brugada ECG pattern. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35(8):e219–e221. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves R.R., Burke R.S. Tramadol: basic pharmacology and emerging concepts. Drugs Today (Barc) 2008;44:827. doi: 10.1358/dot.2008.44.11.1289441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassanian-Moghaddam H., Farajidana H., Sarjami S. Tramadol-induced apnea. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahimi H.R., Soltaninejad K., Shadnia S. Acute tramadol poisoning and its clinical and laboratory findings. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19(9):855–859. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S.Q., Li C.S., Song Y.G. Multiply organ dysfunction syndrome due to tramadol intoxication alone. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(7) doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.11.013. 903.e5-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alizadeh Ghamsari A., Dadpour B., Najari F. Frequency of electrocardiographic abnormalities in tramadol poisoned patients; a brief report. Emergency. 2016;4(3):151–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]