Abstract

Multilocus sequence typing was applied to a collection of 327 clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from China, which was proven to be a good representative of the global diversity of K. pneumoniae. Three lineages L1 to L3 are presented in the population with limited genetic flow across different lineages. However, extremely high levels of recombination can be observed within lineages to the extent at which the alleles are associated almost randomly. Lineages L2 and L3 most likely represent highly specific subgroups of less-virulent K. pneumoniae with modified metabolic networks, while lineage L1 contains not only hypervirulent clones with massive acquisition of virulent genes but also ‘primitive and intermediate forms’ during evolution of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae.

Klebsiella pneumoniae commonly causes nosocomial infections in urinary tract, respiratory tract and blood; under these circumstances, this bacterium is considered as an opportunistic pathogen since it mostly affects debilitated patients1. Nosocomial isolates of K. pneumoniae often display drug resistance phenotypes, making difficulty in choosing sensitive antibiotics for treatment2,3. In addition, a subset of capsular serotypes (including predominantly K1 and K2) constitute hypervirulent variants of K. pneumoniae that have emerged worldwide in the past two decades4,5,6. With increased production of the major virulence determinant capsular polysaccharide, these hypervirulent variants affect previously healthy persons to cause often community-acquired, life-threatening infections such as pyogenic liver abscess, meningitis, and necrotizing fasciitis4,5,6.

Genotyping is important to identify cases or outbreaks due to K. pneumoniae and to further track source and spreading of infections. The major genotyping methods of K. pneumoniae include pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) and multilocus sequence typing (MLST)7,8, and among them MLST is the most popular one. The K. pneumoniae MLST scheme was developed in 20058 and then used globally to characterize diversity and epidemiology of clinical K. pneumoniae isolates, leading to identification of various clones that differ sharply by their features of virulence or drug resistance9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

In our previous study, a genotyping scheme based on the prevalence of 41 large variably-presented gene clusters (LVPCs; four of them correspond to four different virulence loci) plus seven additional virulence markers was established with a collection of 327 clinical isolates of from China, which could be grouped into eight genetically distinct complexes16. K. pneumoniae strains have horizontally acquired various genomic loci including those contributing to virulence during evolution of ‘classic’ opportunistic forms into hypervirulent variants16. In this follow-up study, a modified MLST scheme was established and applied to the same strain collection, providing an extended dissection of population genetics, phylogeny and epidemiology of K. pneumoniae.

Results and Discussion

Extended MLST scheme

The existent K. pneumoniae MLST scheme8 employs seven loci gapA, infB, mdh, pgi, phoE, recA and tonB, and a total of 1595 STs have been deposited in the K. pneumoniae MLST Database (http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/genopole/PF8/mlst/Kpneumoniae.html, last accessed March 20, 2014). When we applied this MLST scheme to our strain collection, redesign of primers (but retaining the locations of allele sequence) brought greatly enhanced amplification success rates for the former six loci; however, repeated attempts with different PCR conditions and primers still led to poor amplification performance for tonB, which was ultimately replaced by the rpoB (beta-subunit of RNA polymerase) gene (Table S1). Poor amplification performance of tonB might be due to frequent insertion/deletion events of one or more codons in the primer annealing regions10. Based on the shared six loci gapA, infB, mdh, pgi, phoE, and recA, we built a NJ tree involving the 1474 STs from the above MLST database plus the 128 STs (see below) from the 327 isolates tested in this study (Figure S1). The uniform scatter of the 128 STs in the NJ tree indicated that our strain collection was a good representative of the global genetic diversity of K. pneumoniae.

Sequence diversity under purifying selection

Sequence alignment of each of the seven loci showed no insertion/deletion, and the concatenated sequence for the seven loci was 2,945 bp in length. There were 273 (9.27%) polymorphic sites detected in total, of which 21 were tri-allelic SNPs (Table 1). The number of alleles found at each DNA fragment ranged from 21 (gapA) to 46 (phoE). The diversity index π was 0.01086 for the concatenated sequences and ranged from 0.0046 (gapA) to 0.0175 (recA) at different loci.

Table 1. Nucleotide and allelic sequence diversity.

| Locus | Length (bp) | No. of alleles | Average G + C content (%) | No. of SNPs | No. of polymorphic sites (%) | Average dN/dS ratio | No. of nonsense mutation | π |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gapA | 450 | 21 | 56.19 | 25 | 25 (5.56) | 0.028 | - | 0.004562 |

| infB | 318 | 22 | 62.37 | 26 | 29 (9.12) | 0.01 | - | 0.010844 |

| mdh | 477 | 27 | 56.67 | 47 | 51 (10.69) | 0.054 | - | 0.014029 |

| pgi | 432 | 29 | 58.41 | 43 | 51 (11.81) | 0.042 | 4 | 0.013856 |

| phoE | 420 | 46 | 55.80 | 48 | 51 (12.14) | 0.139 | - | 0.009281 |

| recA | 347 | 33 | 61.40 | 27 | 29 (8.36) | 0 | - | 0.017538 |

| rpoB | 501 | 24 | 54.98 | 36 | 37 (7.39) | 0.036 | - | 0.007624 |

| Concatenated | 2945 | 128 | 57.61 | 252 | 273 (9.27) | 0.047 | 4 | 0.01086 |

dN/dS > 1 or <1 indicated positive or negative selection on the gene sequence tested, respectively. The dN/dS ratios for the seven loci varied from 0.00 (recA) to 0.139 (phoE), and that for the concatenated sequence was 0.047, indicating strong purifying selection on these genes.

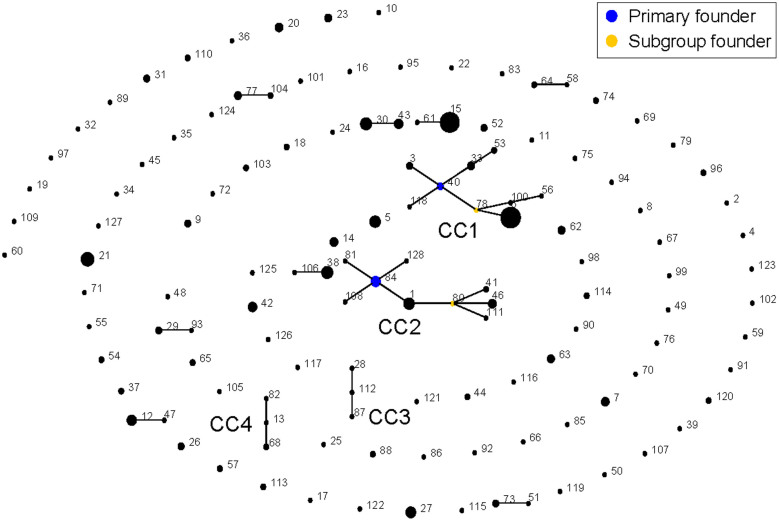

STs and CCs

A total of 128 unique STs were identified from the 327 isolates tested, which were assigned into 4 CCs (CC1 to CC4; 82 strains), 8 doubletons (82 strains) and 88 singletons (163) (Figure 1). CC1 to CC4 contained 9 (47 strains), 9 (28), 3 (3), and 3 (4) STs, respectively. Usually, the predicted founder corresponds to the most predominant ST in a CC17. However, the CC1 founder ST40 contained only three isolates (6.4% of the total 47 strains in CC1), while its DLV descendant ST6 was composed of 31 isolates. Similarly, the CC2 founder ST84 was also not the predominant ST in the complex. This might be resulted from the sampling bias, or due to the reason that the founder ST was swept by selection pressure such as wide application of specific antibiotics in clinic.

Figure 1. Population snapshot.

The population snapshot of the 327 isolates was diagramed by eBURST on the basis of allelic profiles. STs with SLV relationship were linked together to form 4 CCs (CC1 to CC4) and 8 doubletons. The size of the circle represented the number of isolates of each ST.

Three lineages in the whole population

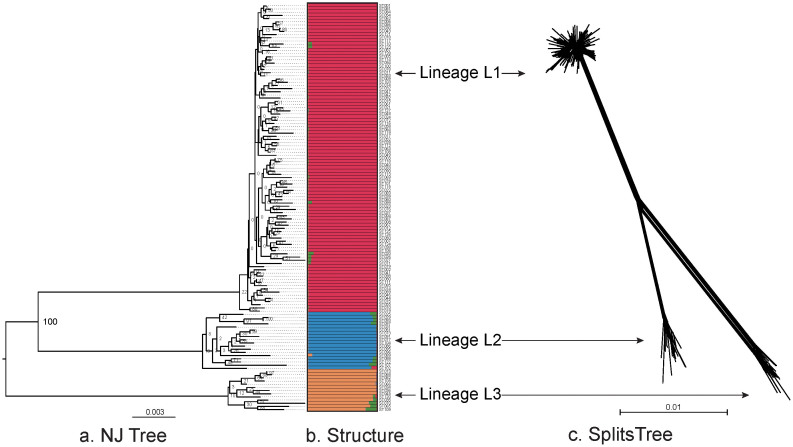

A NJ tree was built from the concatenated sequences of the 128 STs (Figure 2a). Three distinct lineages, termed L1 to L3, were observed with 100% of bootstrap supporting. Remarkably, the bootstrap values on the branches within all the three lineages were extremely low even to zero, suggesting frequent homologous recombination occurred across these branches and eradicated phylogenetic signals of vertical inheritance.

Figure 2. Diagrams denoting population structure.

(a). Unrooted NJ tree of the 128 STs based on the concatenated sequences of 7 loci and the three lineages (L1 to L3) were separated with 100% bootstrap value support. (b). Proportions of ancestral subpopulations of the 128 STs and different colors represented distinct assuming subpopulations corresponding to lineage L1 to L3. (c). Splites network of the 128 STs generated by neighbor-net method using SplitsTree4 based on the concatenated sequences of 7 loci. The three subgroups corresponding to lineage L1 to L3 could be discriminated.

The linkage model of STRUCTURE was applied to the sequence dataset of 128 STs. Multiple runs with K values from 2 to 15 showed maximal posterior probability at K = 4. The 128 STs fell into three distinct subgroups (corresponding to lineage L1 to L3) according to the major ancestral population designation of each ST (Figure 2B). There were little admixture of ancestral sources between these three subgroups, and STs within each subgroup tended to be highly homogenous. In addition, the splits network of the 128 STs also revealed three distinct subgroups corresponding to lineage L1 to L3 (Figure 2c). An overall bifurcating structure was observed from the three lineages with less visualized intersections across different lineages, but each lineage displayed a very complex interconnecting network structure. The above observations further confirmed limited and frequent gene flow across and within lineages, respectively.

In addition, three corresponding major lineages could also be found in the NJ tree of the 128 + 1474 STs (Figure S1). Therefore, the three major lineages would reflect the basic population structure feature of K. pneumoniae of global origins.

Extremely frequent gene flow within lineages

The P value determined by the phi test for the 128 STs (whole population) and those for the ST collections in different lineages were all <0.001, indicating recombination events occurred within and across lineages (Table 2). This result agreed with visualized inspections across and within lineages as determined by SplitsTree (Figure 2c). The detecting per-site ρ/θ value for the 128 STs was 0.42, suggesting point mutation was 2.38 times more likely to occur than recombination at the level of whole population. However, the ρ/θ ratio values were 30.79, 31.94 and 13.12 for lineage L1 to L3, respectively. The recombination frequency within lineages was at least 31 times higher than that across different lineages.

Table 2. Recombination test and estimation.

| Recombination | Linkage disequilibrium | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (n) | phi | theta/site | rho/site | LB 95% | UP 95% | rho/theta | IA | P value |

| Whole (128) | <0.001 | 1.57E-02 | 6.75E-03 | 5.23E-03 | 8.57E-03 | 0.42 | 0.1644 | <0.0001 |

| L1 (97) | <0.001 | 6.55E-03 | 2.02E-01 | 1.04E-01 | 4.25E-01 | 30.79 | 0.0107 | 0.142 |

| L2 (18) | <0.001 | 6.23E-03 | 1.99E-01 | 5.48E-02 | 1.31E+00 | 31.94 | 0.0351 | 0.138 |

| L3 (13) | <0.001 | 6.09E-03 | 7.99E-02 | 5.68E-02 | 1.12E-01 | 13.12 | 0.0507 | 0.0741 |

The st. IA values were 0.0107 (P = 0.142), 0.0424 (P = 0.118) and 0.0507 (P = 0.0741) for lineage L1 to L3, respectively, suggesting a tendency of free recombination between the alleles in each lineage. By contrast, the st. IA of the 128 STs was 0.1644 (P < 0.0001), which was significantly different from zero, indicating a tendency of linkage disequilibrium between the alleles at the level of whole population.

Taken the above together, recombination was highly frequent within lineages but limited across lineages, suggesting natural barriers were presented to prevent gene flow across lineages. Isolates from each sampling city or year could be found in all the three lineages (Figure S2), displaying no evident lineage-specific distribution of isolates with respect to time and geography. Therefore, the natural barriers between lineages might result from high levels of DNA sequence mismatch between donor and recipient18.

Nonsense mutations in pgi

Four kinds of nonsense mutation in pgi were unexpectedly identified from 32 STs (52 isolates), and occurred due to substitution from codon TGG to TGA at nucleotide positions 117, 183, 186 and 216, respectively. The pgi gene encodes the phosphoglucose isomerase, which catalyzes isomerization of glucose 6-phosphate to fructose 6-phosphate in upper glycolysis19. Notably, E. coli lacking pgi remains viable and the loss of pgi forces glycolytic flux through the pentose phosphate pathway, creating a redox imbalance due to excess NADPH production19. Interestingly, pgi nonsense mutations could be found in all the 18 and 13 STs from lineages L2 and L3, respectively. By contrast, only 5 of the 97 STs in L1 presented pgi nonsense mutations. It was speculated that pgi nonsense mutations might have a positive effect on relevant phenotypes, increasing the fitness of the L2 and L3 organisms in specific niches.

Comparison to previous LVPC-based genotyping

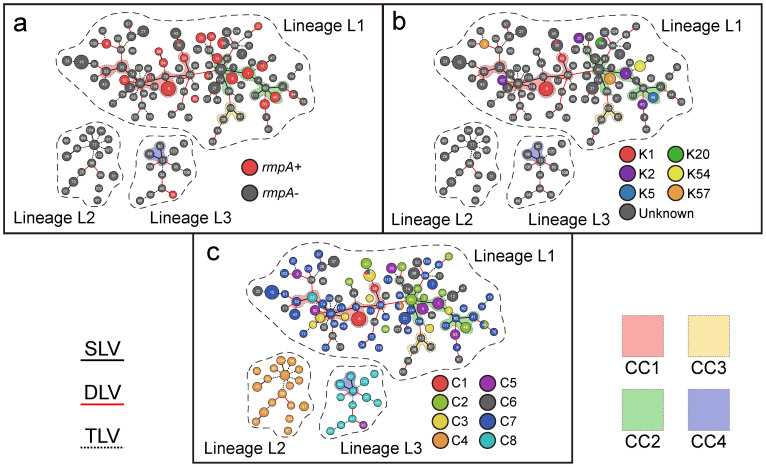

The goeBurst analysis of the allelic profiles of all the 327 strains generated a minimum spanning (MS) tree to provide an intuitive view of the phylogenetic relationships between STs, singletons, doubletons, CCs and lineages (Figure 3). Allelic profile-based phylogenetic relationships as inferred from categorical codes were more reliable than nucleotide-based phylogenies, because replacement of an allele by recombination is scored as a single event20,21. As expected, the structure of the three detected lineages could be illustrated and CC1 to CC3 were found in lineage L1 while CC in L3.

Figure 3. MS tree.

The MS tree of the 128 STs was inferred by Phyloviz on the basis of allelic profiles. Each circle indicated a ST (node), and a larger size of the circle corresponded to a larger number of strains included. The edge between STs represented the relationships of SLV (black and solid), DLV (red and solid) and TLV (black and dash), and a thicker edge corresponded to a shorter phylogenic distance. The dash lines separated three lineages L1 to L3. The background colors indicated different CCs. The prevalence of rmpA (a), capcular serotypes K1, K2, K5, K20, K54, K57 (b) and LVPC complexes C1 to C8 (c) were highlighted with different colors.

The prevalence of rmpA (Figure 3a), capsular serotypes K1, K2, K5, K20, K54 and K57 (Figure 3b) and LVPC-based complexes C1 to C8 (Figure 3c), as characterized previously16, was highlighted in the MS tree. The rmpA gene, which encodes a positive regulator of capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis, is closely associated with the hypervirulent phenotype7,22,23. Twenty-two (99 isolates) of the 128 STs carried rmpA. Except for ST35 (one isolate), all the other rmpA-positive STs belonged to lineage L1. Notably, isolates within each of ST12, ST30, ST38, ST44, ST54 and ST113 may be either rmpA-positive or rmpA-negative. As rmpA was dispersed in different STs and CCs, the spread of this gene in the population might be due to separated events of horizontal gene transfer rather than vertical transmission from a common ancestor.

Except one strain of K54, all the K1, K2, K5, K20, K54, and K57 strains were rmpA-positive, indicating that most of them were closely related to the hypervirulent phenotype16. All these isolates with available serotypes belonged to lineage L1. K1 corresponded to three genetically closed STs (ST6, ST56 and ST30); the former two belonged to CC1 while the last one ST30 differed from ST56 by two alleles. K2 corresponded to ST62, ST63, ST20 and ST1; the former three were singletons while ST1 belonged to CC2. K57 was found in the two singletons ST5 and ST9. K5 were found in ST46 of CC2. K20 or K54 was found in a single singleton ST38 or ST12. The above results were consistent with the previous MLST-based notion that serotypes were not strongly associated with genotype background10.

Lineage L2 exclusively included 30 of the 31 isolates from LVPC-based complex C4, and all STs except for ST35 in L3 corresponded to 15 of the 19 strains from C8. The remaining one and four isolates from C4 and C8, respectively, were attributed to lineage L1. All the L2 and L3 strains were rmpA-negative and moreover C4 and C8 had been characterized as subgroups of less-virulent K. pneumoniae with very limited acquisition of virulent gene loci16, and thus lineages L2 and L3 were mostly like closely related to less-virulent K. pneumoniae. Except for one isolate (ST35) from C5, all isolates of C1, C2, C3, C5, C6 and C7 were included in lineage L1. Lineage L1 appeared to a very complex mixture including not only hypervirulent clones but also ‘primitive and intermediate forms’ during evolution of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae.

Concluding remarks

This is the first report of MLST-based inference of genetic diversity and population structure of clinical K. pneumoniae isolated from China. Notably, our strain collection is a good representative of the global diversity of clinical K. pneumoniae. At least three major lineages L1 to L3 are presented in the K. pneumoniae population with limited horizontal exchange of genetic materials across lineages. However, there are extremely high levels of recombination within lineages to the extent at which the alleles are associated almost randomly (i.e. a tendency to linkage equilibrium). Lineages L2 and L3 most likely represent highly specific subgroups of less-virulent K. pneumoniae with modified metabolic networks, while lineage L1 contains not only hypervirulent clones with massive acquisition of virulent genes but also ‘primitive and intermediate forms’ during evolution of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae. Further genome sequencing study on a large collection of representative clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae will give a much deeper understanding of genetic diversity, phylogeny, population structure and epidemiology of this pathogen.

Methods

Bacterial strains

A total of 327 clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae were tested in this work, all of which were involved in our previous LVPC-based genotyping study16. Beside the reference strain NTUH-K2044 with determined genome sequence24, the remaining 326 strains, being isolated between 2004 and 2009, came from the hospitals in Beijing (North China), Chongqing (Southwest China) and Shenzhen (South China). Genomic DNAs were isolated by classical phenol/chloroform method followed by methoxyethanol removal of polysaccharides that contaminate genomic DNA25, and then arrayed in 96-well PCR plates for further analyses.

PCR amplification and sequencing

PCR primers (Table S2) of target genes were designed with NTUH-K2044 sequences. A volume of 50 μl PCR mixture contained 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH8.0), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.001% gelatin, 0.1% BSA, 100 μM of each dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP, 0.1 μM of each primer, 1 unit of each of ExTaq polymerases (TaKaRa), and 10 ng of genomic DNA. The amplification conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, and then 30 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, an appropriate annealing temperature (Table S2) for 40 s, and 72°C for 1 min. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified by ultrafiltration (Millipore). Both DNA strands were sequenced with PCR primers on ABI-3700 sequencer. DNA sequences were aligned using MUSCLE Version 3.826.

Sequence diversity analyses

The G + C content, number of polymorphic sites, average pairwise nucleotide, and difference per site (π) were calculated with DnaSP Version 5.1027. The average non-synonymous/synonymous rate ratio (dN/dS) was calculated with KaKs Calculator Version 2.028 to infer direction and magnitude of natural selection.

Allelic diversity analyses

DNA sequences of each of the seven MLST loci that differed from each other by one or more polymorphisms were assigned with different allele numbers. Distinct allelic profiles were assigned with different sequence types (STs). Clustering of related STs was carried out by eBURST Version 317. Two different STs sharing six of the seven loci constituted a single-locus variant (SLV). A double-locus variant (DLV) contained two STs differing in two loci and other loci should be identical. A triple-locus variant (TLV) included two STs differing in three loci. A clonal complex was composed of at least three STs with only SLVs. Only two STs belong to the same group with SLV was called doublet. The remaining STs, which had no SLV with other STs, were termed singletons. The founders (ancestry types) of CCs were predicted with 1,000 re-samplings for bootstrap.

Population structure analyses

The Neighbor Joining (NJ) method29 was used to build phylogenetic trees of strains or STs. STRUCTURE software Version 2.330,31,32,33 was used with linkage model to infer ancestry of STs, and this procedure assumed that each ST was derived from K assuming ancestral subpopulations. The proportions for each ST of K subpopulations could be estimated and illustrated. The posterior probability P(X|K) was calculated to determine which K to choose, where X stood for the number of genotypes of sampled isolates. 14 individual runs (20,000 burn-in iterations and 30,000 iterations sampling iterations) per value of K ranged from 2 to 15 were performed and 4 was chosen as the appropriate ancestry number with maximal posterior probability. The splits network of STs was generated by neighbor-net method34 using SplitsTree435. Global optimal eBURST implemented by Phyloviz36 was used to cluster STs with triple-locus variant (TLV) limitation, generating a MS tree to visualize possible evolutionary relationships between STs.

Recombination analyses

The phi test for recombination was performed with SplitsTree435, and P values < 0.05 indicated recombination existed. The Linkage Analysis Version 3.637 was used to calculate standardized index of association (st. IA) with 10,000 iterations by Monte Carlo based on allelic profiles. If there was linkage equilibrium because of frequent recombination events, the expected value of st. IA was zero, which suggested no association between alleles at different loci; if st. IA was statistically significant different from zero, alleles were suggested with genetic linkage. The LDhat program38,39 implemented in the RDP4 package40 was used to calculate per-site ρ/θ ratios based on concatenated sequences of the seven loci with 1,000,000 MCMC updates. The parameters ρ and θ represented the rates of recombination and mutation respectively.

Supplementary Material

3 Supplementary material V2

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1021992), National Key Program for Infectious Diseases of China (2013ZX10004216 and 2012ZX10004215), and National Basic Research Program of China (2014CB744400).

Footnotes

Author Contributions D.Z., Y.C. and L.H. designed experiments. C.G., X.Y., Y.W., H.Y., Y.H., R.Y., L.H., Y.C. and D.Z. performed experiments. C.G., D.Z. and Y.C. analyzed data. B.L., C.G., D.Z., Y.C. and Y.W. contributed reagents, materials and analysis tools. D.Z., C.G., Y.C. and L.H. wrote this manuscript.

References

- Podschun R. & Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 589–603 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson D. L. et al. International prospective study of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in nosocomial Infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 140, 26–32 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keynan Y. & Rubinstein E. The changing face of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in the community. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30, 385–389 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu L. K., Yeh K. M., Lin J. C., Fung C. P. & Chang F. Y. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect. Dis. 12, 881–887 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shon A. S. & Russo T. A. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: the next superbug? Future Microbiol. 7, 669–671 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shon A. S., Bajwa R. P. & Russo T. A. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence 4, 107–118, 10.4161/viru.22718 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turton J. F., Perry C., Elgohari S. & Hampton C. V. PCR characterization and typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae using capsular type-specific, variable number tandem repeat and virulence gene targets. J. Med. Microbiol. 59, 541–547 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diancourt L., Passet V., Verhoef J., Grimont P. A. & Brisse S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 4178–4182 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. et al. Genotypic Analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates in a Beijing Hospital Reveals High Genetic Diversity and Clonal Population Structure of Drug-Resistant Isolates. PLoS One 8, e57091, 10.1371/journal.pone.0057091 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisse S. et al. Virulent clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification and evolutionary scenario based on genomic and phenotypic characterization. PLoS One 4, e4982, 10.1371/journal.pone.0004982 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada S. et al. Familial spread of a virulent clone of Klebsiella pneumoniae causing primary liver abscess. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 2354–2356 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu L. K. et al. Molecular typing and virulence analysis of serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from liver abscess patients and stool samples from noninfectious subjects in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 3761–3765 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. C. et al. Genotypes and virulence in serotype K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae from liver abscess and non-infectious carriers in Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan. Gut. Pathog. 6, 21, 10.1186/1757-4749-6-21 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Wang Y., Ye L. & Yang J. Molecular epidemiology and virulence factors of pyogenic liver abscess causing Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect., 10.1111/1469-0691.12664 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Mathema B., Pitout J. D., DeLeo F. R. & Kreiswirth B. N. Epidemic Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 is a hybrid strain. MBio 5, e01355–14, 10.1128/mBio.01355-14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. et al. A novel PCR-based genotyping scheme for clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae. Future Microbiol. 9, 21–32 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil E. J., Li B. C., Aanensen D. M., Hanage W. P. & Spratt B. G. eBURST: inferring patterns of evolutionary descent among clusters of related bacterial genotypes from multilocus sequence typing data. J. Bacteriol. 186, 1518–1530 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matic I., Radman M. & Rayssiguier C. Structure of recombinants from conjugational crosses between Escherichia coli donor and mismatch-repair deficient Salmonella typhimurium recipients. Genetics 136, 17–26 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charusanti P. et al. Genetic basis of growth adaptation of Escherichia coli after deletion of pgi, a major metabolic gene. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001186, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001186 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt B. G., Hanage W. P. & Feil E. J. The relative contributions of recombination and point mutation to the diversification of bacterial clones. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4, 602–606 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno A. et al. Recombining population structure of Plesiomonas shigelloides (Enterobacteriaceae) revealed by multilocus sequence typing. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7808–7818 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. L. et al. Association between rmpA and magA genes and clinical syndromes caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42, 1351–1358 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. R., Lin T. L., Chen Y. C., Chou H. C. & Wang J. T. The role of Klebsiella pneumoniae rmpA in capsular polysaccharide synthesis and virulence revisited. Microbiology, 157, 3446–3457 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K. M. et al. Genome sequencing and comparative analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae NTUH-K2044, a strain causing liver abscess and meningitis. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4492–4501 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X. et al. Two methods for extraction of high-purity genomic DNA from mucoid Gram-negative bacteria. Afric. J. Microbiol. Res. 5, 4013–4018 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P. & Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Zhu J. & Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 8, 77–80 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N. & Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J. K., Stephens M. & Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush D., Stephens M. & Pritchard J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164, 1567–1587 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush D., Stephens M. & Pritchard J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 574–578 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubisz M. J., Falush D., Stephens M. & Pritchard J. K. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 9, 1322–1332 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D. & Moulton V. Neighbor-Net: an agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. in Algorithms in Bioinformatics, 375–391 (Springer, 2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruen T. C., Philippe H. & Bryant D. A simple and robust statistical test for detecting the presence of recombination. Genetics 172, 2665–2681 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco A. P. et al. PHYLOViZ: phylogenetic inference and data visualization for sequence based typing methods. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 87 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubold B. & Hudson R. R. LIAN 3.0: detecting linkage disequilibrium in multilocus data. Linkage Analysis. Bioinformatics 16, 847–848 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean G. A. et al. The fine-scale structure of recombination rate variation in the human genome. Science 304, 581–584 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auton A. & McVean G. Recombination rate estimation in the presence of hotspots. Genome Res. 17, 1219–1227 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. P. et al. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics 26, 2462–2463 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

3 Supplementary material V2