Abstract

Problem addressed

Aspiring physician writers need an environment that promotes self-reflection and can help them improve their skills and confidence in writing.

Objective of program

To create a peer-support writing group for physicians in the Markham-Stouffville community in Ontario to promote professional development by encouraging self-reflection and fostering the concept of physician as writer.

Program description

The program, designed based on a literature review and a needs assessment, was conducted in 3 sessions over 6 months. Participants included an emergency physician, 4 family physicians, and 3 residents. Four to 8 participants per session shared their projects with guest physician authors. Eight pieces of written work were brought to the sessions, 3 of which were edited. A mixed quantitative and qualitative evaluation model was used with preprogram and postprogram questionnaires and a focus group.

Conclusion

This program promoted professional development by increasing participants’ frequency of self-reflection and improving their proficiency in writing. Successful elements of this program include creating a supportive group environment and having a physician-writer expert facilitate the peer-feedback sessions. Similar programs can be useful in postgraduate education or continuing professional development.

Résumé

Problème à l’étude

Les médecins désireux d’écrire ont besoin d’un environnement qui favorise l’auto-réflexion, et qui les rend plus habiles et plus confiants en leur capacité d’écrire.

Objectif

Créer un groupe d’aide à la rédaction composé de pairs chez des médecins de la communauté Markham-Stouffville afin de promouvoir le développement professionnel en encourageant l’auto-réflexion et en insistant sur le concept de médecin-auteur.

Description du programme

Conçu à partir d’une revue de la littérature et d’une évaluation des besoins, le programme comprenait 3 sessions sur une durée de 6 mois. Les participants comprenaient un médecin des urgences, 4 médecins de famille et 3 résidents. Dans chacune des sessions, entre 4 et 8 participants discutaient de leurs suggestions de texte avec des médecins-auteurs invités. Parmi les huit textes écrits discutés durant les sessions, 3 ont été publiés. Une évaluation quantitative-qualitative de type mixte a été effectuée à l’aide de questionnaires avant et après le programme ainsi que par un groupe de discussion.

Conclusion

Le programme a favorisé le développement professionnel en augmentant la fréquence à laquelle les participants recouraient à l’auto-réflexion et en améliorant leur capacité d’écrire. Parmi les éléments les plus efficaces du programme, mentionnons la création d’un groupe local d’aide et le fait que la présence de médecins-auteurs experts facilitait les sessions de rétroaction par des pairs. De tels programmes pourraient être utilisés dans les programmes de formation de troisième cycle ou dans la formation médicale continue.

As Mimi Divinsky expressed in a 2007 commentary published in Canadian Family Physician, reflective practice prevents physicians from becoming “the kind of doctors who go down the hall to see ‘the gallbladder in room 2.’ Diseases don’t ‘present’; people become ill.”1

Being able to reflect on clinical encounters through narrative medicine encourages health care providers to explore their personal and professional values.1–8 Reflective experiences improve patient care, decrease physician burnout, and increase job satisfaction.3,4 Narrative medicine is increasingly adopted into medical education.4,9,10 Furthermore, fostering the concept of the physician as writer is broadly applicable, from those interested in creative writing and engaging the public through media platforms, such as news editorials and blogs, to those interested in academic publication. Narrative medicine has the capacity to promote professional development by encouraging reflective clinical practice and fostering the concept of physician as writer.

Applying a collaborative approach in the form of a peer-support writing group (PSWG) can address the barriers cited by physicians interested in writing, including perceived lack of writing skills, low self-confidence, and writer’s block, and can also increase academic productivity.11–15 The Department of Family Medicine at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver applied the well cited benefits of a facilitative group writing process to design a PSWG that encouraged participants to assist each other in preparing manuscripts and writing projects for submission in a safe and supportive environment.11 The PSWG had 15 clinician participants over a 36-month period, resulting in increased writing productivity and confidence in their ability to write. Another PSWG that took place in the Faculty of Medicine at McGill University in Montreal, Que, which consisted of 3 sessions and a workshop for 24 physicians, showed that the participants valued the peer feedback. Although there was no change in the number of publications in a survey completed 5 years later, there was an increase in education-related publications.12 At Memorial University of Newfoundland in St John’s, a faculty development program that consisted of a writing workshop and individual consultations with experienced journal editors and researchers found increased confidence and writing productivity among participants.16 At the University of Alberta in Edmonton, a monthly PSWG, which comprised 7 faculty members, that implemented committed membership and regular goal setting over 18 months enhanced writing productivity and encouraged educational scholarship.17

Despite the importance of the concept of the physician writer, writing programs are not a formal component of family medicine postgraduate education or continuing professional development.

Program objective

There is a need among community primary care physicians for a collaborative writing group to develop effective writing skills, create an environment to promote self-reflection, and encourage publication. Based on this premise, a pilot PSWG was designed and implemented in the Markham-Stouffville primary care community in Ontario in 2014 to 2015 to promote professional development in writing proficiency among aspiring physician writers.

Program description

Participant recruitment.

The target audience recruited for the needs assessment and membership in the PSWG consisted of 21 family medicine residents and 34 family physicians, as well as allied health professionals, at affiliated family health groups and teams in Markham; and 43 emergency medicine physicians at the Markham Stouffville Hospital. Participant recruitment was conducted via e-mail communication, in addition to flyers and word of mouth.

Needs assessment.

Over a 1-month period, there was an estimated 20% response rate to the survey. The needs assessment revealed diverse interests in writing, including writing for the public, as well as reflective, creative, and academic writing. Barriers to writing included lack of confidence due to limited time and mentorship. A need to improve writing skills for publication and to promote self-reflection was identified.

Program design.

Both the University of Toronto and the Markham Stouffville Hospital research ethics boards were consulted and a review was deemed unnecessary.

The program structure was informed by the literature and the needs assessment. The program was to consist of five 2-hour evening workshops over a 6-month period, but 2 workshops had to be canceled owing to unforeseen conditions (Table 1).18–20 The first component involved a discussion with guest physician writers. Supported by the needs assessment survey results, the PSWG focused on providing writing tools and an opportunity for mentorship. Based on the writing interests identified in the survey, a variety of guest physician writers were invited. The second component consisted of a peer-feedback session facilitated by an expert physician writer. Structured in line with the Canadian PSWGs in the literature, members were asked to share at least one piece of writing and the group provided constructive feedback and resources.

Table 1.

Program workshops: 2 of the 5 program workshops were canceled.

| SESSION | DATE | GUEST AUTHOR |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | September 17, 2014 | Dr Nicholas Pimlott, Scientific Editor of Canadian Family Physician |

| 2 | October 29, 2014 | Dr Geordie Fallis, author of From Testicles to Timbuktu: Notes from a Family Doctor18 |

| 3 | January 20, 2015 | Dr Brian Goldman, host of CBC Radio show White Coat, Black Art, author of The Night Shift: Real Life in the Heart of the E.R.19 and The Secret Language of Doctors20 |

Program evaluation.

A quasi-experimental preprogram and postprogram design was conducted for data collection. Informed consent was obtained. All 8 participants completed the preprogram and postprogram questionnaires. A focus group of 4 participants was conducted at the end of the program using both preset questions and open discussion. A mixed quantitative and qualitative analysis model was used. The focus group data were transcribed and coded independently by 2 investigators (L.A., J.Y.). Thematic analysis was performed through the combination of related codes into overarching themes within the preconceived framework of self-reflection and physician as writer.

Exploratory themes were also noted.

Participant profile.

The PSWG consisted of 8 participants: 1 emergency medicine physician, 4 family physicians, and 3 family medicine residents. There was an estimated 6.5% response rate for joining the PSWG. Three participants attended all 3 sessions, 2 attended 2 of the sessions, and 3 attended 1 session. The main barrier to attending all the sessions was timing conflict.

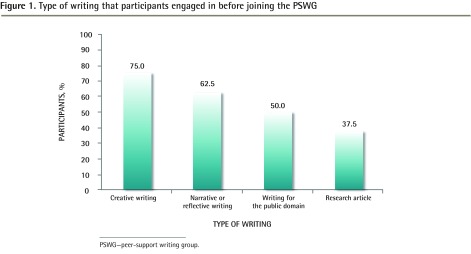

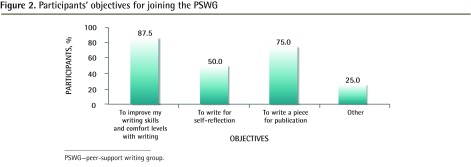

Creative writing and narrative or reflective writing were the types of writing that most of the participants engaged in before joining the PSWG (Figure 1). Figure 2 presents participants’ objectives for joining the program.

Figure 1.

Type of writing that participants engaged in before joining the PSWG

PSWG—peer-support writing group.

Figure 2.

Participants’ objectives for joining the PSWG

PSWG—peer-support writing group.

Peer-feedback component.

At least 6 written pieces were brought by participants, but 3 were shared. Four out of the 8 participants brought at least one written piece, and 3 participants did not bring any pieces. Barriers to bringing pieces included lack of confidence in presenting to expert writers, and particularly for residents in sharing with attending physicians.

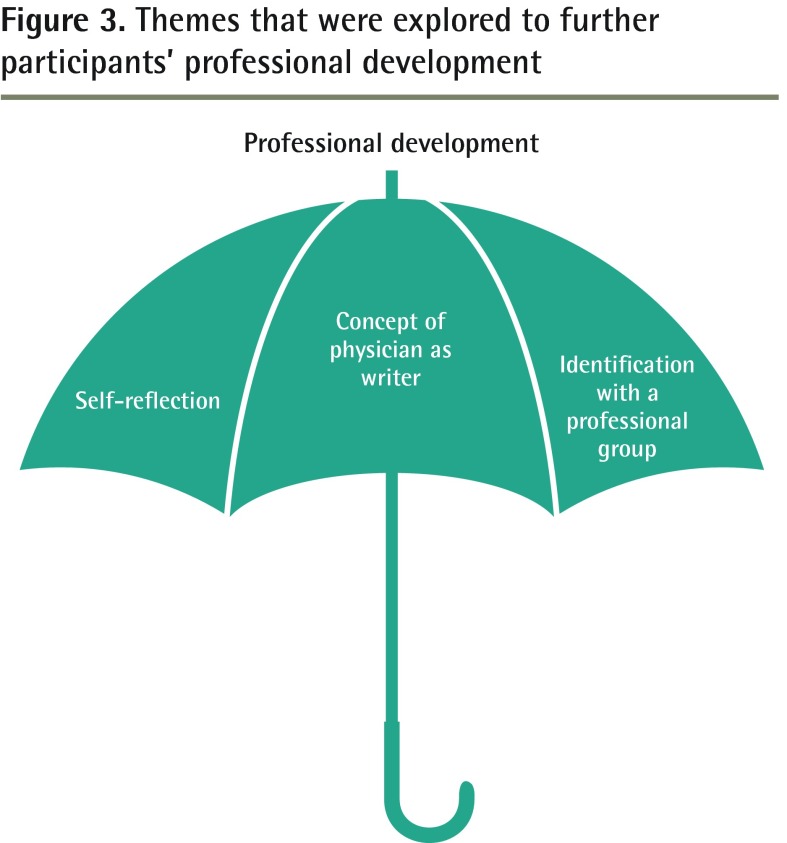

Role of PSWG in professional development

Professional development was explored under the umbrella of 2 themes: self-reflection and the concept of physician as writer, which was measured through perceived writing proficiency. Identification with a professional group was an additional theme that emerged (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Themes that were explored to further participants’ professional development

Increasing frequency of self-reflection.

Four out of 8 participants described an increased frequency of self-reflection after attending the PSWG workshops.

It made me wonder, if I saw patients, whether they would be stories … I read through [Dr Fallis’18] book, and it’s just like, “This is what happened on Monday,” and you know, I have a lot of Mondays.

It helped me to look for the stories in my encounters, and to be more reflective.

Two participants commented on how the process of preparing and participating in the discussion of others’ work led to greater reflective practice. “If you’re going to a writing group … you think … maybe we’re going to talk about some of the things that [someone] has written … I better … think about it.”

One participant also found a benefit to the process of sharing one’s own work. “I think it caused reflection … trying to read something you’ve written with new eyes …. Why did I write that?”

Fostering the concept of physician as writer.

The project investigated how a PSWG influenced the participants’ perceived proficiency with writing in terms of 2 themes: perceived writing skills and writing frequency. Six out of 8 participants thought that their writing skills improved. They found that the writing tips and resources provided were useful in developing a “writing tool kit.”

Just sit down and write … is like saying to someone, just sit down and paint, but it’s like, “How do I make orange?” I think there are some skills that are helpful to learn so you can work within that … otherwise we’d all just be published tomorrow.

Feeling inspired to write, hence increasing writing frequency, was also a component that one of the guest authors, Dr Pimlott, emphasized. Seven out of 8 participants believed the PSWG inspired them to write more. One participant mentioned how hearing the guest writers’ perspectives inspired a personal writing journey. “As budding writers, it’s helpful to hear people’s stories … that’s the thing I benefited from the most … knowing what stories got them interested.”

Many found that regular attendance created a sense of accountability, which in turn increased writing frequency.

I think I found it motivating … to make sure I sit down and do it … even though no one pushes you—a bit of accountability … if you’re going to a writing group … thinking more about writing again … more consistently.

Identifying with a professional group.

An additional aspect of professional development that the PSWG encouraged was participants having a professional group that they could identify with. Participants perceived a supportive environment and a sense of community, which extended beyond the program. “The following week we were in clinic together ... and started talking about all sorts of stuff. I don’t think that would have happened if we didn’t have this forum.”

On the other hand, participants thought that while the PSWG helped develop a sense of group identity, the duration was too short to become comfortable with sharing their work.

Everyone needs to be willing to put themselves out there and that’s a little bit intimidating.

The feeling that you put yourself out there often comes after you’ve been with a group for a while and you feel that you have a safe place.

Participant opinion

Seven out of 8 participants were satisfied with the PSWG and open to engaging in future PSWGs. Participants found value in the consistent presence of a physician-writer expert, but also appreciated the contributions from various guest authors (Box 1).

Box 1. Participant opinions about the PSWG program.

Participants found that the PSWG program provided ...

a consistent presence of expert physician writers to facilitate the peer-feedback process

a mix of community-based and academic physicians and residents

guest authors who could provide networking opportunities

an informal, interactive, and supportive environment

Participants believed that the PSWG program could be improved by ...

increasing the duration

scheduling sessions during lunch as opposed to after hours

providing firm expectation to share written pieces

mandating homework exercises

PSWG—peer-support writing group.

Discussion

The needs assessment demonstrated that there is an unmet need to create an environment such as a collaborative PSWG to promote self-reflection and enhance writing proficiency for community physicians.

Overall, most participants found the PSWG to be a valuable opportunity that they would pursue again. Compared with the other Canadian PSWGs described in the literature, this program was unique because of the consistent presence of an expert physician writer who facilitated the peer-editing process, as well as the inclusion of guest physician authors. This served to surpass the barrier of the limited mentorship opportunities identified by the participants.

The findings suggest that the PSWG provided a meaningful contribution to professional development. First, participants believed that the PSWG increased their frequency of reflective practice, which is known to enhance the empathic doctor-patient relationship by enabling doctors to explore experiences from a wider perspective.1,13 Second, the PSWG enhanced the role of the physician as writer. The PSWG helped the participants develop a “writing tool kit” for greater writing proficiency, and also inspired them to write more frequently. As such, it encouraged participants to work toward their writing goals—whether they be writing for reflection, publication, a creative outlet, or public health advocacy. Finally, our findings highlight an important aspect of professional development that resulted from the PSWG: identifying with a group of professionals with similar interests in writing. The longitudinal nature, small group size, and informal setting created by the comfortable room and the presence of food all fostered a supportive environment. Other PSWGs also found an increased sense of cohesiveness, support, and group camaraderie among participants.4,8,14,15,17

Limitations

The biggest drawback of the program’s evaluation was its short duration, as this limited participants’ comfort in sharing their work. It is also unclear whether having guest physician authors is sustainable for longer programs. A further possible limitation is that the participants were a self-selected group of physicians interested in writing, and it is unclear whether the program would be as successful if implemented widely. It also might be useful to include the perspective of allied health care providers and non–family physician specialists. Finally, although the sample size was small, it was ideal for an exploratory qualitative study.

Conclusion

There is a need among community primary care physicians to develop effective writing tools as an important component of professional development. A PSWG is a valuable opportunity for promoting self-reflection and the concept of physician as writer. The program’s successful elements include fostering a supportive group environment and providing a consistent presence of an expert physician writer who facilitates the sessions. Similar programs would be useful in postgraduate education and continuing professional development.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Drs Jane Philpott, Michael Coons, and Sumairah Syed for their support. This is an educational scholarship project conducted at the academic Markham Family Medicine Teaching Unit, which is affiliated with the University of Toronto’s Department of Family and Community Medicine. As a resident project, it received both financial and material support from the teaching unit.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

In writing for both publication and personal fulfilment, aspiring physician writers face barriers such as perceived lack of writing skills and low self-confidence. Applying a collaborative approach in the form of a peer-support writing group (PSWG) can address these barriers.

To address the need for a collaborative writing group among community primary care physicians, a pilot PSWG was designed and implemented in the Markham-Stouffville primary care community in Ontario. This PSWG program was designed to help physicians develop effective writing skills, provide an environment to promote self-reflection, and encourage publication.

Valuable components of this program included having physician-writer experts facilitate the peer-feedback process and having guest physician authors who could provide guidance and networking opportunities. With the program’s informal, interactive, and supportive environment, aspiring physician writers increased their frequency of self-reflection and developed an understanding of the concept of physician as writer.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Lorsqu’un médecin envisage de rédiger un texte, que ce soit pour une publication ou pour des raisons personnelles, il peut en être dissuadé s’il croit ne pas être suffisamment habile en rédaction ou en raison d’un manque de confiance en soi. Grâce à la collaboration d’un groupe d’aide à la rédaction composé de pairs (GARP), on peut minimiser ces obstacles.

Pour vérifier l’intérêt d’avoir un groupe d’aide à la rédaction chez des médecins de première ligne, on a créé et mis en place un GARP pilote au sein de la communauté de Markham-Stouffville. La création de ce programme avait pour but d’aider les médecins à devenir plus habiles en rédaction, de fournir un environnement favorable à l’auto-réflexion et d’encourager la publication.

Parmi les avantages du programme, mentionnons que la présence de médecins-auteurs experts facilite le processus de rétroaction des pairs, et que ces médecins-auteurs invités peuvent donner des conseils et fournir des occasions de travailler en réseau. Grâce à la nature interactive et informelle du programme, et à l’atmosphère de soutien qui le caractérise, les médecins désireux d’écrire ont recouru plus souvent à l’auto-réflexion et ont mieux compris ce que signifie écrire quand on est médecin.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Drs Al-Imari and Yang designed and implemented the program; conducted the program evaluation; and wrote the article. Dr Pimlott was the supervising attending physician who provided guidance throughout the project.

Competing interests

Dr Pimlott is Scientific Editor of Canadian Family Physician.

References

- 1.Divinsky M. Stories for life. Introduction to narrative medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:203–5. (Eng), 209–11 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charon R. What to do with stories. The sciences of narrative medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1265–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatem D, Ferrara E. Becoming a doctor: fostering humane caregivers through creative writing. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisman AB, Hansen H, Rastegar A. The craft of writing: a physician-writer’s workshop for resident physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1109–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00550.x. Epub 2006 Jul 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasman DL. “Doctor, are you listening?” A writing and reflection workshop. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):549–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scannell K. Writing for our lives: physician narratives and medical practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(9):779–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-9-200211050-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verghese A. The physician as storyteller. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(11):1012–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arntfield SL, Slesar K, Dickson J, Charon R. Narrative medicine as a means of training medical students toward residency competencies. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(3):280–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.014. Epub 2013 Feb 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterkin A, Roberts M, Kavanagh L, Havey T. Narrative means to professional ends. New strategies for teaching CanMEDS roles in Canadian medical schools. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e563–9. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/58/10/e563.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2016 Nov 4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grzybowski S, Bates J, Calam B, Alred J, Martin R, Andrew R, et al. A physician peer support writing group. Fam Med. 2003;35(3):195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinert Y, McLeod PJ, Liben S, Snell L. Writing for publication in medical education: the benefits of a faculty development workshop and peer-support writing group. Med Teach. 2008;30(8):e280–5. doi: 10.1080/01421590802337120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson D. Mentored residential writing retreats: a leadership strategy to develop skills and generate outcomes in writing for publication. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.05.018. Epub 2008 Aug 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houfek JF, Kaiser KL, Visovsky C, Barry TL, Nelson AE, Kaiser MM, et al. Using a writing group to promote faculty scholarship. Nurse Educ. 2010;35(1):41–5. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0b013e3181c42133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ness V, Duffy K, McCallum J, Price L. Getting published: reflections of a collaborative writing group. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.03.019. Epub 2013 Apr 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bethune C, Asghari S, Godwin M, McCarthy P. Finding their voices. How a group of academic family physicians became writers. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:1067–8. (Eng), 1073–4 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walton J, White J, Stobart K, Lewis M, Clark M, Oswald A. Group of seven: eMERGing from the wilderness together. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallis G. From testicles to Timbuktu: notes from a family doctor. Toronto, ON: Flawlis Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldman B. The night shift: real life in the heart of the E.R. Toronto, ON: HarperCollins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman B. The secret language of doctors. Toronto, ON: HarperCollins; 2014. [Google Scholar]