Abstract

Observations from studies during the last decade have changed the conventional view of cystic fibrosis (CF) microbiology, which has traditionally focused on a limited suite of opportunistic bacterial pathogens. It is now appreciated that CF airways typically harbor complex microbial communities, and that changes in the structure and activity of these communities have a bearing on patient clinical condition and lung disease progression. Recent studies of gut microbiota also suggest that disordered bacterial ecology of the CF gastrointestinal tract is associated with pulmonary outcomes. These new insights may alter future clinical management of CF.

Keywords: Microbiota, Lung, Gut, Bacteria, Fungi, Virus, Culture-independent

Key points

-

•

Culture-independent investigations have revealed a complex community of microbes, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, harbored in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF).

-

•

Bacterial community composition in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts is heterogeneous between patients with CF, such that unique microbial signatures are generally patient specific.

-

•

Evidence suggests that gut microbiota composition in CF may influence disease features both within and beyond the gut, but further research is needed.

-

•

Culture-independent characterization of microbial community composition is complemented by methods that provide insight into functional features of the microbiome and mechanistic relationships to clinical outcomes.

-

•

Multiomic analyses of airway and gut microbiota have the potential to refine current management strategies in CF.

Introduction

Recent elucidation of the richness and complexity of the microbiome in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) has invigorated new discussions of the role of microbial infection in CF beyond pathogens classically linked to CF, like Pseudomonas aeruginosa. An increasing number of studies have characterized the composition of airway microbiota in patients from different CF cohorts,1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and common threads have emerged across studies in the relationships observed between features of the respiratory microbiome and clinical outcomes. However, extending these observations to the clinical realm in a predictive manner remains a challenge for several reasons, including the interpatient heterogeneity in airway microbiota composition that has come to be appreciated from these studies.

Most studies to date have focused on bacterial members of the respiratory microbiome, but some recent investigations have also begun to characterize fungal and viral communities in CF.13, 14, 15, 16 Such efforts are important because these other microbial kingdoms have largely been ignored in the schema of lung microbiome investigation. In addition, recent studies have begun to explore the microbiome in other organs affected by CF, such as the gastrointestinal tract.17, 18, 19, 20 Because gut dysfunction is another prominent feature of CF, findings from these studies may have important clinical implications.21

This article highlights recent insights in the rapidly evolving area of CF microbiome investigation. Advances in knowledge about the nature of microbial dysbiosis (ie, altered microbial balance) in CF are reshaping the conceptual framework within which the role of infection in CF has long been considered. Select studies are discussed that have contributed to the current understanding of the structure, composition, and collective functions of CF microbiota, and their relationship to disease benchmarks. In addition, both the challenges and opportunities presented from these recent insights are discussed in terms of how such knowledge may be leveraged to inform the care of patients with CF.

Overview of methods and considerations in lung microbiome investigation

Advances in sequence-based analysis of microbial genomes have laid the foundation for techniques to characterize the types of microbial species present in a sample. For bacteria, the most widely used approaches are based on analysis of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene, whose conservation across species, along with polymorphisms in hypervariable regions of the gene, enables both the broad detection of bacteria present in a sample and their phylogenetic identities. For more comprehensive discussions regarding methods and tools to study the microbiome, including in the context of lung disease, readers are referred to recent articles in this area.22, 23, 24

The unique anatomy of the lung presents challenges to studying its microbiome. Collecting lower airway samples requires passage through the upper respiratory tract or oropharynx, which has previously raised questions about the extent of oral contamination in such samples. However, several studies now have established that microbiota identified from lower respiratory specimens are distinguishable from upper airway microbiota (especially nasopharyngeal) in measures of diversity and also in the types and relative abundance of specific bacterial groups.25, 26, 27, 28, 29 Moreover, the architecture of the bronchial airways leads to regional differences in lung biology and the airway microenvironment, even in the healthy state.30 In CF, it is likely that patterns of dysbiosis are greatly influenced by the altered airway milieu related to CF transmembrane receptor dysfunction and subsequent changes to mucus clearance.31

The cystic fibrosis respiratory microbiome

Bacteria: Culture-based Investigations

Bronchiectasis and chronic infection are well-recognized clinical features of CF that contribute the most to disease morbidity and mortality. Although it is well established that P aeruginosa is an important pathogen in CF lung disease, other bacteria that also contribute to pulmonary morbidity in CF include Burkholderia cepacia complex,32 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus,33 and certain nontuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium abscessus complex or Mycobacterium avium complex.34 Microbiological features of these organisms, including factors responsible for virulence and resistance to antimicrobial therapies, have been extensively studied.35, 36 Additional potential pathogens associated with CF include Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Achromobacter spp, including Achromobacter xylosoxidans and Achromobacter ruhlandii, which can be difficult to treat.37, 38, 39, 40, 41

The role of anaerobic bacteria in CF lung disease remains uncertain, but they are frequently identifiable and prevalent by both culture-targeted and culture-independent methods.2, 42, 43, 44, 45 Current data support an argument for anaerobes playing an important role in the CF airway microenvironment, especially given the steep oxygen gradients present.45 In addition to contributing to the CF antibiotic resistome (ie, the collection of all antibiotic resistance genes in microorganisms), certain prevalent anaerobic species produce quorum-sensing molecules that mediate interspecies signaling pathways46 and potentially influence virulence characteristics of pathogens like P aeruginosa.47 More recent evidence also suggests that metabolic products associated with anaerobes,43, 48 including short-chain fatty acids detected in airway specimens, may increase the release of interleukin (IL)-8, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and IL-6 and reduce inducible NOS (nitric oxide synthase) gene expression. Thus anaerobic bacteria may be a group of keystone organisms that collectively have a large influence on the CF pulmonary ecosystem.

Bacteria: Culture-independent Molecular Studies

Culture-independent investigations within the past 10 to 15 years have expanded and are reshaping traditional views of CF airway microbiology. Across both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of CF respiratory samples, several similar observations have been made.

First, studies of respiratory samples from young children with CF have noted that several distinct bacterial groups are present in both directly sampled, CF-affected lung tissue26 and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.1, 11 Coupled with the knowledge that structural and physiologic function of the lung is compromised in the early life of CF-affected children,49, 50 this suggests a direct relationship between the early development of microbial dysbiosis in the lungs and these clinical outcomes.

Second, airway bacterial diversity in patients with CF is greatest in early life up to adolescence, declining thereafter into adulthood. These observations have been made from both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, including 1 birth cohort study that found that bacterial diversity in the first 2 years of life was influenced by feeding habit and that a decline in specific bacteria, such as Haemophilus, preceded colonization of P aeruginosa.12 Similar trends have been observed from cross-sectional analyses across different age groups.3, 4 Selective pressure from cumulative courses of antibiotics is the predominant factor shaping this change in bacterial community structure.7

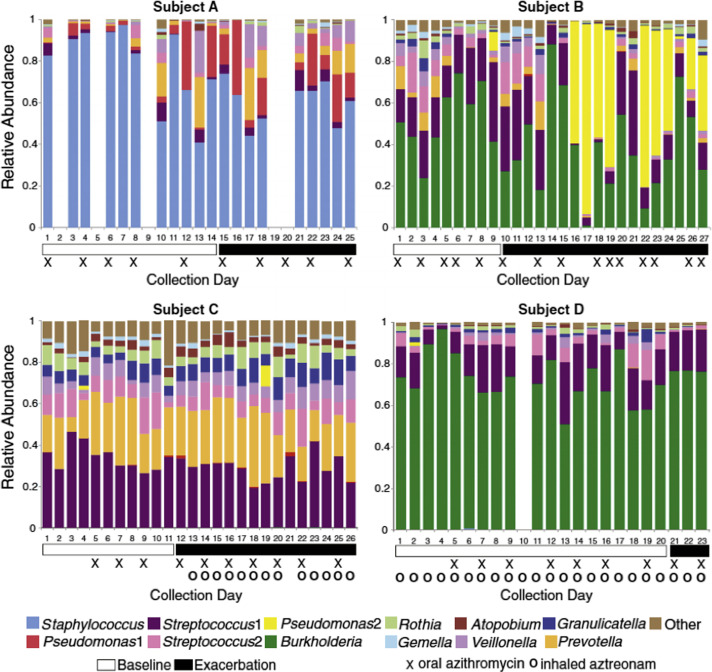

Third, studies in adults with CF have observed great heterogeneity among patients in the composition of bacterial communities identified from airway samples (mostly sputum).2, 6, 8 That is, the types and relative abundance of different bacterial groups detected vary considerably between patients, as shown by a representative example from one study (Fig. 1 ). Another consistent finding is that bacterial groups that are most prevalent within a patient also do not tend to vary substantially in relative abundance over time. The most prevalent communities identified by culture-independent investigations mirror those species or genera detected in clinical cultures, such as P aeruginosa, Burkholderia, and Staphylococcus. When prevalent, these bacterial groups in essence represent core members of the CF respiratory microbiome, but results of culture-independent analyses suggest that additional bacterial groups, not usually detected by typical CF clinical culture methods, comprise this core. For example, using approaches that partition the distribution of species based on statistical variance/abundance ratios, investigators in one study reported that, in addition to Pseudomonas, anaerobic species, such as members of the Porphyromonas, Prevotella, and Veillonella genera, also contribute to their study cohort’s core group of microbiota (a total of 15 taxa from 7 genera).5 This finding contrasted with the greater range of bacterial groups (67 taxa from 33 genera) comprising a satellite group of microbiota, which did not correlate with any clinical factors. However, whether satellite species nonetheless contribute ecological interactions of importance within the CF microbiome remains an outstanding question.

Fig. 1.

Representative example of the heterogeneity between different patients with CF in bacterial community composition of sputum. The relative abundance of the top operational taxonomic units identified in daily sputum samples collected from 4 subjects during periods of clinical stability (white horizontal bars) and onset of exacerbation (black horizontal bars). Symbols below the plots indicate days when maintenance antibiotics were taken. Each plot ends on the day preceding the prescription of antibiotics for treatment of exacerbation.

(From Carmody LA, Zhao J, Kalikin LM, et al. The daily dynamics of cystic fibrosis airway microbiota during clinical stability and at exacerbation. Microbiome 2015;3:12; with permission under Creative Commons Attribution License.)

An implication of these findings is that a molecular-based bacterial community signature that distinguishes patients clinically has been difficult to ascertain. For example, in CF pulmonary exacerbations, no consistent changes in airway bacterial burden or community composition have been observed among patients within a given study or compared across studies.6, 7, 51 Some patients show marked shifts in their respiratory bacterial community structures at a given exacerbation, whereas others show very little change despite clinical symptoms suggestive of such events. Moreover, patients across different studies have shown exacerbation-related reductions in the abundance of baseline predominant species, suggesting that increased abundance of less prevalent microbiota members may play a greater role in certain exacerbations. In addition, antibiotic treatments for exacerbations do not cause a sustained shift in bacterial community structure following exacerbation.6, 7 The CF airway microbiome is generally resilient to these perturbations with community reassembly after recovery resembling a patient’s baseline community structure.7

Fungal Microbiota in Cystic Fibrosis

Characterization of fungal microbial communities (mycobiome”) has in general lagged behind studies of bacteria, and only recently have some advances been made in respiratory studies.52, 53, 54 Several factors make identifying fungi and analysis of the mycobiome challenging.52 Similar to bacteria, most fungal species are difficult, if at all possible, to culture.55 As such, the application of high-throughput sequencing approaches has better delineated the diversity of fungal species harbored in the lungs, and in the context of respiratory disease.53, 54 However, approaches for sample preparation, from extraction of fungal DNA and choice of primers to amplify fungal sequences, are nonuniform across studies and that can influence readouts of fungal composition.52 Moreover, existing reference databases for comparing fungal sequences are less rich and robust than those for bacteria (eg, 16S ribosomal RNA databases), further limiting analytical efforts. Investigators considering such studies should therefore be cognizant of factors that could bias or limit fungal community characterization.

Notwithstanding these challenges, several studies have explored the respiratory mycobiome in CF. In a study of sputum samples from 4 patients with CF, 60% of the identified fungal taxa were not detected by mycological cultures.13 In addition to Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus, 30 fungal species or genera identified included other species of Candida and Aspergillus, Penicillium, Malassezia, and Kluyveromyces. Another study of 6 subjects with CF found that a mixture of Candida and Malassezia species dominated 74% to 99% of fungal sequence reads from sputum, although the samples were collected at the time of admission, and after completion of antibacterial therapy, which could influence these findings.14 One of the largest studies to date, involving 56 patients,54 found that the number of fungal species detected in CF sputum was higher than that for bacteria but also fluctuated much more over time. The investigators concluded that this suggests that inhalational exposure is a greater driving factor in the detection of fungi than established fungal colonization in CF airways. Other culture-independent, nonsequencing approaches to identify fungal species, such as denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography,15 have also been explored using CF sputa. However, the utility of this approach compared with others remains uncertain.

Viral Microbiota in Cystic Fibrosis Airways

Infections by RNA viruses (eg, rhinovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenzae) are important triggers of CF pulmonary exacerbations.56, 57, 58, 59 However, few studies have examined the respiratory virome in CF, in part because of the challenges of conducting comprehensive viral sequencing studies.60 Several studies have focused on bacteriophage populations in the airways.16, 61, 62, 63 Because these DNA viruses infect specific bacteria, specific phages have been studied as alternative therapeutic approaches to potentially target particular bacterial pathogens, like P aeruginosa.62, 63

Metagenomic studies that provide a more comprehensive picture of DNA viruses in the respiratory tract of patients with CF have noted CF-associated phage communities to be highly similar to each other, in contrast with those found in patients without CF.16 This finding likely reflects the range of bacterial species selected for in the CF lung. High phage/bacteria ratios have been described in a variety of mucosal environments, including human gingival samples, and in vitro studies have shown phage adherence to mucus to be mediated by binding interactions between immunoglobulinlike domains on phage capsids and glycan residues on mucin glycoproteins.64 Further, pretreatment of mucus-producing cell lines with T4 phages led to subsequent decreased bacterial attachment (Escherichia coli) to the cells. These findings have led investigators to propose that bacteriophage adherence to mucus may serve as a form of antibacterial immunity along mucosal surfaces. However, the potential significance of this system extrapolated to the CF lung remains unclear. Other data also suggest that phages may be functionally synergistic with antibiotics, wherein antibiotics stimulate phage production and/or activity to aid bacterial killing.65 Lytic activity of temperate phages may also be preserved long-term in chronic P aeruginosa infection and potentially contribute to controlling P aeruginosa density.62

Functional features of the cystic fibrosis microbiome

Compositional studies of the microbiota harbored within patients with CF have broadened the knowledge of microbial diversity associated with this disease. However, it is likely that the functions and metabolic features encoded for, and expressed by, a collective microbial community span species-level differences in taxonomic composition, which in itself is nonuniform across patients. Evidence for this cross-phylogeny sharing of gene functions has been found in the gut microbiome, via known mechanisms such as horizontal gene transfer between bacteria,66 and has served as a premise for the development of in silico approaches to determine functional capacities of bacterial microbiota based on metagenome predictions.67

Using a combined metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approach in which sequencing of both DNA and RNA were performed, Quinn and colleagues68 examined the functional capacities of microbiota detected from the sputa of patients with CF. Enriched functions expressed by CF-associated organisms included amino acid catabolism, folate biosynthesis, and nitrate reduction pathways, with the nitrate reduction pathways largely encoded by Pseudomonas and Rothia. Their data also suggested that ammonia may accumulate in the airway environment, because oxidative pathways involved in the nitrogen cycle were incomplete.

Artificial culture systems have also been applied in attempts to simulate and study CF microbial-related physiology in the airways.69 One approach used glass capillary tubes instilled with artificial sputum medium intended to mimic CF physiologic conditions, which were then inoculated with bacterial strains derived from patients with CF collected serially during periods of clinical stability and exacerbation. Using a combination of techniques to evaluate the physiology of the system, the investigators observed increased gas production and a 2-unit reduction in pH before the onset of exacerbation. Parallel analysis of the microbial community noted an increase in the abundance of fermentative anaerobes, suggesting that metabolic activities of these organisms may contribute to the development of exacerbations.

The gastrointestinal microbiome in cystic fibrosis

Although studies of respiratory microbiota have dominated CF microbiome studies, recently investigations have also begun to characterize and analyze relationships between gastrointestinal bacterial microbiota, clinical disease markers, and profiles of airway bacterial community composition. Gastrointestinal complications of CF are a significant cause of disease morbidity, and problems beyond pancreatic insufficiency are often difficult to manage.21 Two studies17, 18 involving a cohort of patients with CF found that numbers of Enterobacteriaceae were marginally higher in CF fecal samples, whereas there was significant underrepresentation of Bifidobacterium and members of Clostridium cluster XIVa. Two-year longitudinal analysis of 2 patients with CF and their healthy siblings observed a trend toward lower species richness and temporal stability of CF fecal microbiota.17

Patterns of gut and respiratory microbiome development in early life in children with CF have been reported in 2 studies from a single birth cohort.19, 20 Although the number of subjects was small, the investigators observed initial diversification in gut and respiratory microbiota composition, followed by subsequent shifts in community composition related to changes in diet, namely cessation of breastfeeding and introduction of solid foods. Although children without CF were not included as a control group for comparison in these studies, this observation is consistent with normal patterns of gut microbiome maturation in early life in healthy infants.70, 71 Changes in diet also influenced respiratory microbiota composition, indicating links to nutritional intake.19 Decreases in specific bacterial genera, both in the gut (Parabacteroides) and in the respiratory tract (Haemophilus), preceded airway colonization with P aeruginosa.20 Another interesting observation was that intestinal, but not respiratory, bacterial community structure in the first 6 months of life was associated with the occurrence of CF exacerbations during that time frame. Findings from these types of studies, as well as those from interventional trials using probiotic species,72, 73 suggest that manipulations of the gut microbiome to foster a less proinflammatory environment could be an avenue to mitigate pulmonary morbidity in CF.

Future directions in cystic fibrosis microbiome research

The new insights afforded by the studies described earlier provide a foundation for addressing several important questions pertaining to the microbiology of CF. As clinicians continue to explore the long-term dynamics of airway bacterial community structure, a focus will be on better elucidating the relationship between decreasing community diversity and advancing patient age and lung disease. An intriguing question is whether maintaining more diverse communities might have a positive impact on lung health, and, if so, whether novel treatment strategies (eg, targeted species-specific antimicrobial therapy) may enable maintenance of healthier airway communities. A more complete understanding of short-term community dynamics may identify reproducible changes in community structure and/or activity that are associated with changes in patient clinical condition. If multiomic analyses identify, for example, biomarkers of impending exacerbation, it will be of great interest to determine whether these can be monitored in real time and exploited to prevent or better manage these events. Similarly, specific patterns of community change may be identified that predict exacerbation severity and/or recovery.

Moving forward, it will be important to complement the growing understanding of bacterial ecology in CF airways with attention to the broader microbial community, including viral and fungal species. Advances in the appreciation of how microbial interactions drive the activity of polymicrobial communities are expected to provide opportunities for novel therapies. In addition, continued investigation of the relationship between disordered gut microbiota and lung disorder in CF has the potential to translate to creative management strategies and to generate mechanistic hypotheses addressing CF pathobiology.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Harris J.K., De Groote M.A., Sagel S.D. Molecular identification of bacteria in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from children with cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(51):20529–20533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709804104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tunney M.M., Field T.R., Moriarty T.F. Detection of anaerobic bacteria in high numbers in sputum from patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:995–1001. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1151OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox M.J., Allgaier M., Taylor B. Airway microbiota and pathogen abundance in age-stratified cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klepac-Ceraj V., Lemon K.P., Martin T.R. Relationship between cystic fibrosis respiratory tract bacterial communities and age, genotype, antibiotics and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:1293–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Gast C.J., Walker A.W., Stressmann F.A. Partitioning core and satellite taxa from within cystic fibrosis lung bacterial communities. ISME J. 2011;5(5):780–791. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fodor A.A., Klem E.R., Gilpin D.F. The adult cystic fibrosis airway microbiota is stable over time and infection type, and highly resilient to antibiotic treatment of exacerbations. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao J., Schloss P.D., Kalikin L.M. Decade-long bacterial community dynamics in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(15):5809–5814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120577109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmody L.A., Zhao J., Kalikin L.M. The daily dynamics of cystic fibrosis airway microbiota during clinical stability and at exacerbation. Microbiome. 2015;3:12. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price K.E., Hampton T.H., Gifford A.H. Unique microbial communities persist in individual cystic fibrosis patients throughout a clinical exacerbation. Microbiome. 2013;1(1):27. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zemanick E.T., Harris J.K., Wagner B.D. Inflammation and airway microbiota during cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renwick J., McNally P., John B. The microbial community of the cystic fibrosis airway is disrupted in early life. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e109798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coburn B., Wang P.W., Diaz Caballero J. Lung microbiota across age and disease stage in cystic fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10241. doi: 10.1038/srep10241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delhaes L., Monchy S., Fréalle E. The airway microbiota in cystic fibrosis: a complex fungal and bacterial community–implications for therapeutic management. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willger S.D., Grim S.L., Dolben E.L. Characterization and quantification of the fungal microbiome in serial samples from individuals with cystic fibrosis. Microbiome. 2014;2:40. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mounier J., Gouëllo A., Keravec M. Use of denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) to characterize the bacterial and fungal airway microbiota of cystic fibrosis patients. J Microbiol. 2014;52(4):307–314. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-3425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willner D., Furlan M., Haynes M. Metagenomic analysis of respiratory tract DNA viral communities in cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis individuals. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duytschaever G., Huys G., Bekaert M. Cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons of the predominant fecal microbiota compositions of a group of pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis and their healthy siblings. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(22):8015–8024. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05933-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duytschaever G., Huys G., Bekaert M. Dysbiosis of bifidobacteria and Clostridium cluster XIVa in the cystic fibrosis fecal microbiota. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12(3):206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madan J.C., Koestler D.C., Stanton B.A. Serial analysis of the gut and respiratory microbiome in cystic fibrosis in infancy: interaction between intestinal and respiratory tracts and impact of nutritional exposures. MBio. 2012;3(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00251-12. [pii:e00251–12] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoen A.G., Li J., Moulton L.A. Associations between gut microbial colonization in early life and respiratory outcomes in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2015;167(1):138–147.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelfond D., Borowitz D. Gastrointestinal complications of cystic fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(4):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.006. [quiz: e30–1] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han M.K., Huang Y.J., Lipuma J.J. Significance of the microbiome in obstructive lung disease. Thorax. 2012;67(5):456–463. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Y.J., Charlson E.S., Collman R.G. The role of the lung microbiome in health and disease. A National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(12):1382–1387. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0488WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickson R.P., Erb-Downward J.R., Huffnagle G.B. The role of the bacterial microbiome in lung disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2013;7(3):245–257. doi: 10.1586/ers.13.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris A., Beck J.M., Schloss P.D. Lung HIV microbiome project. Comparison of the respiratory microbiome in healthy nonsmokers and smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(10):1067–1075. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1913OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown P.S., Pope C.E., Marsh R.L. Directly sampling the lung of a young child with cystic fibrosis reveals diverse microbiota. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(7):1049–1055. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201311-383OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zemanick E.T., Wagner B.D., Robertson C.E. Assessment of airway microbiota and inflammation in cystic fibrosis using multiple sampling methods. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(2):221–229. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boutin S., Graeber S.Y., Weitnauer M. Comparison of microbiomes from different niches of upper and lower airways in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0116029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venkataraman A., Bassis C.M., Beck J.M. Application of a neutral community model to assess structuring of the human lung microbiome. MBio. 2015;6(1) doi: 10.1128/mBio.02284-14. [pii:e02284–14] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickson R.P., Erb-Downward J.R., Huffnagle G.B. Towards an ecology of the lung: new conceptual models of pulmonary microbiology and pneumonia pathogenesis. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(3):238–246. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70028-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willner D., Haynes M.R., Furlan M. Spatial distribution of microbial communities in the cystic fibrosis lung. ISME J. 2012;6(2):471–474. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilligan P.H. Infections in patients with cystic fibrosis: diagnostic microbiology update. Clin Lab Med. 2014;34(2):197–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2014.02.001. [Review] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dasenbrook E.C., Checkley W., Merlo C.A. Association between respiratory tract methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and survival in cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2386–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martiniano S.L., Nick J.A. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in cystic fibrosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(1):101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.11.003. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolter D.J., Emerson J.C., McNamara S. Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants are independently associated with worse lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(3):384–391. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muhlebach M.S., Heltshe S.L., Popowitch E.B., The STAR-CF Study Team Multicenter observational study on factors and outcomes associated with different MRSA types in children with cystic fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(6):864–871. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201412-596OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cogen J., Emerson J., Sanders D.B., EPIC Study Group Risk factors for lung function decline in a large cohort of young cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50(8):763–770. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parkins M.D., Floto R.A. Emerging bacterial pathogens and changing concepts of bacterial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2015;14(3):293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Baets F., Schelstraete P., Van Daele S. Achromobacter xylosoxidans in cystic fibrosis: prevalence and clinical relevance. J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6(1):75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambiase A., Catania M.R., Del Pezzo M. Achromobacter xylosoxidans respiratory tract infection in cystic fibrosis patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(8):973–980. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1182-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marzuillo C., De Giusti M., Tufi D. Molecular characterization of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates from cystic fibrosis patients and the hospital environment. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(8):753–758. doi: 10.1086/598683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tunney M.M., Klem E.R., Fodor A.A. Use of culture and molecular analysis to determine the effect of antibiotic treatment on microbial community diversity and abundance during exacerbation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2011;66:579–584. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.137281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Twomey K.B., Alston M., An S.Q. Microbiota and metabolite profiling reveal specific alterations in bacterial community structure and environment in the cystic fibrosis airway during exacerbation. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chmiel J.F., Aksamit T.R., Chotirmall S.H. Antibiotic management of lung infections in cystic fibrosis. II. Nontuberculous mycobacteria, anaerobic bacteria, and fungi. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(8):1298–1306. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201405-203AS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones A.M. Anaerobic bacteria in cystic fibrosis: pathogens or harmless commensals? Thorax. 2011;66(7):558–559. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.157875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Field T.R., Sibley C.D., Parkins M.D. The genus Prevotella in cystic fibrosis airways. Anaerobe. 2010;16(4):337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duan K., Dammel C., Stein J. Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene expression by host microflora through interspecies communication. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50(5):1477–1491. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghorbani P., Santhakumar P., Hu Q. Short-chain fatty acids affect cystic fibrosis airway inflammation and bacterial growth. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(4):1033–1045. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00143614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramsey K.A., Ranganathan S., Park J. Early respiratory infection is associated with reduced spirometry in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(10):1111–1116. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1277OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wielpütz M.O., Puderbach M., Kopp-Schneider A. Magnetic resonance imaging detects changes in structure and perfusion, and response to therapy in early cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(8):956–965. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1659OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carmody L.A., Zhao J., Schloss P.D. Changes in cystic fibrosis airway microbiota at pulmonary exacerbation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(3):179–187. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201211-107OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cui L., Morris A., Ghedin E. The human mycobiome in health and disease. Genome Med. 2013;5(7):63. doi: 10.1186/gm467. [Review] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nguyen L.D., Viscogliosi E., Delhaes L. The lung mycobiome: an emerging field of the human respiratory microbiome. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:89. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00089. [Review] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kramer R., Sauer-Heilborn A., Welte T. A cohort study of the airway mycobiome in adult cystic fibrosis patients: differences in community structure of fungi compared to bacteria reveal predominance of transient fungal elements. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(9):2900–2907. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01094-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagano Y., Elborn J.S., Millar B.C. Comparison of techniques to examine the diversity of fungi in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Med Mycol. 2010;48:166–176. doi: 10.3109/13693780903127506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goffard A., Lambert V., Salleron J. Virus and cystic fibrosis: rhinoviruses are associated with exacerbations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2014;60(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Esther C.R., Jr., Lin F.C., Kerr A. Respiratory viruses are associated with common respiratory pathogens in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(9):926–931. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flight W.G., Bright-Thomas R.J., Tilston P. Incidence and clinical impact of respiratory viruses in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2014;69(3):247–253. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asner S., Waters V., Solomon M. Role of respiratory viruses in pulmonary exacerbations in children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11(5):433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wylie K.M., Weinstock G.M., Storch G.A. Emerging view of the human virome. Transl Res. 2012;160(4):283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.03.006. [Review] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim Y.W., Schmieder R., Haynes M. Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics: windows on CF-associated viral and microbial communities. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12(2):154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.James C.E., Davies E.V., Fothergill J.L. Lytic activity by temperate phages of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in long-term cystic fibrosis chronic lung infections. ISME J. 2015;9(6):1391–1398. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saussereau E., Vachier I., Chiron R. Effectiveness of bacteriophages in the sputum of cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(12):O983–O990. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barr J.J., Auro R., Furlan M. Bacteriophage adhering to mucus provide a non-host-derived immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10771–10776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305923110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamal F., Dennis J.J. Burkholderia cepacia complex phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS): antibiotics stimulate lytic phage activity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(3):1132–1138. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02850-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smillie C.S., Smith M.B., Friedman J. Ecology drives a global network of gene exchange connecting the human microbiome. Nature. 2011;480:241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature10571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Langille M.G., Zaneveld J., Caporaso J.G. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quinn R.A., Lim Y.W., Maughan H. Biogeochemical forces shape the composition and physiology of polymicrobial communities in the cystic fibrosis lung. MBio. 2014;5(2):e00956-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00956-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quinn R.A., Whiteson K., Lim Y.W. Winogradsky-based culture system shows an association between microbial fermentation and cystic fibrosis exacerbation. ISME J. 2015;9(4):1024–1038. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.234. [Erratum appears in ISME J 2015;9(4):1052] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saavedra J.M., Dattilo A.M. Early development of intestinal microbiota: implications for future health. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2012;41(4):717–731. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bäckhed F., Roswall J., Peng Y. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(5):690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.del Campo R., Garriga M., Pérez-Aragón A. Improvement of digestive health and reduction in proteobacterial populations in the gut microbiota of cystic fibrosis patients using a Lactobacillus reuteri probiotic preparation: a double blind prospective study. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(6):716–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bruzzese E., Callegari M.L., Raia V. Disrupted intestinal microbiota and intestinal inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis and its restoration with Lactobacillus GG: a randomised clinical trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]