Abstract

Background/aim

Aggressive benign or malignant tumors in the proximal fibula may require en bloc resection of the fibular head, including the peroneal nerve and lateral collateral ligament. Here, we report the treatment outcomes of 12 patients with aggressive benign or malignant proximal fibula tumors.

Patients and methods

Four patients with osteosarcoma and 1 patient with Ewing's sarcoma were treated with intentional marginal resections after effective chemotherapy, and 4 patients underwent fibular head resections without ligamentous reconstruction. Clinical outcomes were investigated.

Results

The mean Musculoskeletal Tumor Society scores were 96% and 65% in patients without peroneal nerve resection and those with nerve resection, respectively. No patients complained of knee instability.

Conclusion

Functional outcomes after resection of the fibular head were primarily influenced by peroneal nerve preservation. If patients are good responders to preoperative chemotherapy, malignant tumors may be treated with marginal excision, resulting in peroneal nerve preservation and good function.

Keywords: Proximal fibular tumor, Reconstruction, Fibular head resection

1. Introduction

Osteosarcomas (OS), giant cell tumors (GCT), and chondrosarcomas (CS) rarely arise in the proximal fibula, as tumors of the fibula account for only 2.5% of all primary bone tumors [1], [2]. Approximately one-fourth of all primary bone tumors in the fibula are malignant [2], and approximately one-fourth of all benign bone tumors in the fibula are GCT. Aggressive benign tumors such as GCT and malignant tumors in the proximal fibula often require en bloc resection of the fibular head, including the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and the attachment site of the biceps femoris muscle tendon. Fibular head resection may cause postoperative knee instability because the LCL is the main resistor of varus loading. However, unlike traumatic disruption of the lateral structures of the knee, the need for reconstruction of the LCL after tumor excision is controversial. The majority of traumatic posterolateral knee injuries occur in combination with other ligamentous injuries [3], the most common of which affect the anterior cruciate ligament or posterior cruciate ligament [4]. During proximal fibular tumor excision, these ligaments are often preserved.

Peroneal nerve palsy and local recurrence are serious postoperative complications associated with resection of these tumors. Based on the literature, the incidence rate of postoperative peroneal nerve palsy ranges from 3% to 57% [5], while local recurrence rates vary by tumor histology and resection type.

In this study, we investigated the clinical outcomes of 12 patients with aggressive benign or malignant proximal fibula tumors, especially in terms of the necessity for LCL reconstruction and the impact of peroneal nerve resection on postoperative function.

2. Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed our institution's medical records to identify all patients with tumors of the proximal fibula surgically treated between 1992 and 2011. Nonoperative cases were excluded. The proximal epiphysis was involved in all patients. The clinical outcomes of all patients were investigated. All patients approved the use of their data for this study, and this study was approved by the ethics committee at our institution.

We surgically treated 12 patients (7 men, 5 women). The mean age at presentation was 31 years (range, 11–71 years). Preoperative metastatic workups were performed by chest X-ray in all patients, and especially by chest CT in all patients of malignancy. Patients were followed up for a minimum of 2.7 years (median, 5.2 years; range, 2.7–13.4 years) at intervals of 2 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, and 5 years postoperatively. Follow-up intervals and durations were determined individually for each patient and according to tumor pathology.

Presenting symptoms were available for 10 patients, and these included pain (9/10), a palpable mass (1/10), and peroneal nerve symptoms (3/10).

Histological diagnoses were OS (4/12), malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH; 2/12), Ewing's sarcoma (EWS; 1/12), GCT (4/12), and low-grade CS (1/12).

We analyzed surgical methods, oncologic outcomes, functional results, and complication rates among patients. Surgical methods were classified into 3 types: intralesional excision, marginal excision, and wide excision (Fig. 1). Functional results were assessed using Musculoskeletal Tumor Society scores, in which numerical values (scores ranging from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating poor function and 30 indicating good function) are assigned to each of 6 categories: pain, function, emotional acceptance, support, walking, and gait. Data were expressed as a percentage of total scores between 0 and 30.

Fig. 1.

Surgical methods. (A) Marginal excision and reconstruction. (B) Wide excision.

3. Results

Intralesional excision was performed in 4 GCT patients by curettage and adjuvant therapy with burring, cryotherapy, and alcohol. Intentional marginal excision was performed in 4 OS patients and 1 EWS patient following effective caffeine-potentiated chemotherapy in which the histological responses of resected specimens were classified as Grade IV (Rosen and Huvos) [6]. One patient with low-grade CS without extraskeletal lesions and 2 patients with recurrent GCT were also treated with marginal excision of the fibular head. Wide excision, including peroneal nerve resection, was performed for 2 MFH patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of patient demographics, diagnosis, treatment, complication, oncologic and functional outcome.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | M | FS | 13.4 | CDF | 100 | Intentional Marginal | + | − | − | − | Suture anchor |

| 2 | 17 | M | OS | 10.2 | CDF | 100 | Intentional Marginal | + | − | − | − | Spike washer |

| 3 | 11 | M | OS | 9.9 | CDF | 100 | Intentional Marginal | + | − | − | − | Suture |

| 4 | 14 | F | OS | 5.3 | DOD | 100 | Intentional Marginal | + | − | − | − | Spike washer |

| 5 | 49 | M | CS | 3.7 | CDF | 93 | Marginal | + | − | − | − | Spike washer |

| 6 | 21 | M | GCT | 3.7 | NED | 93 | Marginal | + | − | − | − | Spike washer |

| 7 | 30 | F | GCT | 5.1 | NED | 100 | Marginal | + | + | − | − | – |

| 8 | 49 | F | MFH | 5.4 | CDF | 70 | Wide | − | − | 40 | Peroneal nerve palsy | – |

| 9 | 58 | F | GCT | 2.8 | CDF | 70 | Currettage | + | + | − | Peroneal nerve palsy and DVT | Intact |

| 10 | 24 | M | GCT | 4.7 | CDF | 100 | Currettage | + | + | − | Wound infection | Intact |

| 11 | 13 | M | EWS | 10.1 | CDF | 100 | Intentional Marginal | + | − | 30 | − | – |

| 12 | 71 | F | MFH | 2.7 | AWD | 60 | Wide | − | − | 40 | Peroneal nerve palsy and wound dehiscence | – |

A – Patient

B – Age

C – Sex

D – Diagnosis. FS: Fibrosarcoma, OS: Osteosarcoma, CS: Chondrosarcoma (low-grade),

GCT: Giant cell tumor, MFH: Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, EWS: Ewing's sarcoma

E – Follow up period (years)

F – Outcome. CDF: continuous disease free, NED: no evidence of disease, AWD: alive with disease

G – MSTS Score (%)

H – Operative method

I – Attempt to preserve peroneal nerve

J – Intra-operative adjuvant treatment: A; burring, liquid nitrogen spray, alchohol

K – Postoperative radiotherapy (Gy)

L – Complication. DVT: deep venous thrombosis

M – Reconstruction of Lateral Collateral Ligament.

Ten patients, including 2 with recurrent GCT, were treated by fibular head resection. Four patients, including 2 MFH patients, 1 EWS patient, and 1 recurrent GCT patient, were treated by fibular head resection without ligamentous reconstruction. In the other 6 patients who underwent fibular head resection, the LCL and biceps tendon were reattached to the lateral tibia with suture anchors, a spike washer, or just sutures.

At a median follow-up of 5.2 years, 8 patients were disease-free (median follow-up, 7.7 years), 2 patients had no evidence of disease (median follow-up, 4.4 years), 1 patient was alive with disease, and 1 OS patient died of disease. The OS patient never had local recurrence though metastatic tumors were detected 2 years after first operation.

The mean Musculoskeletal Tumor Society score in patients without peroneal nerve resection was 96% (range, 70–100%), while that in patients with peroneal nerve resection was 65% (range, 60–70%). Permanent peroneal nerve palsy, despite nerve preservation, occurred in 1 of 10 patients. Deep venous thrombosis (1/12) also occurred in the same patient during a period of bed rest following neurolysis; therefore, anticoagulant therapy was required. Three patients with postoperative peroneal nerve palsy required foot orthoses. No patients complained of knee instability; however, among patients who were treated without ligamentous reconstruction, 1 patient exhibited knee varus instability when compared with the unaffected side on a varus stress test (Fig. 2).

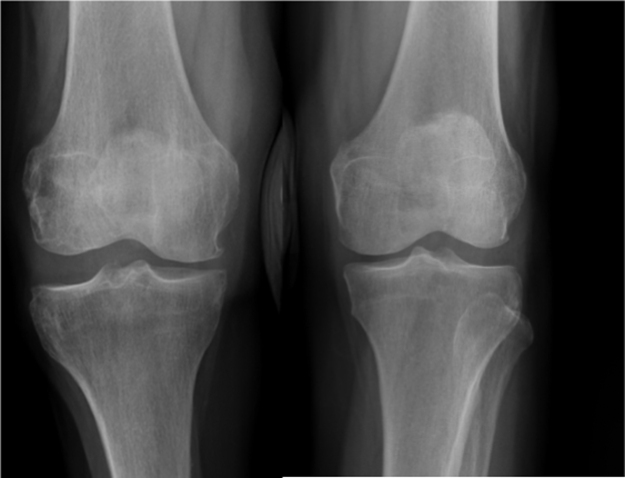

Fig. 2.

X-ray film of the varus stress test at the last follow-up in 1 fibular head tumor patient who was treated by fibular head resection without reconstruction. Varus instability was detected in the right knee (side on which the operation was performed) in comparison with the healthy side.

Regarding postoperative complications, wound dehiscences, which take 3–36 weeks for full recovery, occurred in 2 of 12 patients. Local recurrence (2/12) occurred in GCT patients who were treated with curettage and adjuvant therapy. As mentioned above, 2 local recurrences of GCT were treated with marginal excision of the fibular head. Lung metastases occurred in 1 OS patient and 1 MFH patient.

4. Discussion

Tumors of the proximal fibula are rare. Because of the anatomical characteristics of this location, varus instability, peroneal nerve palsy, and local recurrence are common, yet serious, complications that may arise following tumor resection.

The necessity of reconstructing the LCL after tumor excision is controversial because other knee stabilizers, such as the anterior cruciate ligament or posterior cruciate ligament, are intact following surgery for proximal fibular tumors. In this study, 4 patients without LCL reconstruction did not exhibit any knee instability. Einoder et al. also reported good function after fibular head resection without ligamentous reconstruction in 6 patients [7]. However, in this study, 1 patient exhibited instability on a varus stress test (Fig. 1). In contrast, Abdel et al. reported no long-term knee instability with repair of LCL in 112 patients with aggressive benign tumors and 53 patients with malignant fibular tumors [5], [8]. They assessed knee instability using the varus stress test at 30° knee flexion. Therefore, if possible, LCL reconstruction should be considered after fibular head resection, especially in young patients.

With resection of the fibular head for aggressive benign or malignant tumors, our patients had good functional results with regard to subjective symptoms and activities of daily life. Postoperative function is mainly influenced by the incidence of peroneal nerve palsy, and the need for support with peroneal braces is the most influential factor affecting patients' daily life [9], [10]. If patients respond well to preoperative chemotherapy, as we previously reported, even malignant tumors could be treated by marginal excision to preserve the peroneal nerve [6].

Local recurrences occurred in 2 out of 4 GCT patients who were treated with curettage and adjuvant therapy. As Abdel et al. recommended [5], GCT located in the proximal fibula should be treated with en bloc resection because of the clear difference in the local recurrence rate. They reported a local recurrence rate of 67% (2/3 patients) among patients with GCT treated with intralesional excision compared to 11% (2/18 patients) among patients with GCT treated with en bloc excision [5]. Because of higher surgical stress and risk in cases of recurrence, we recommend that patients be treated with en bloc excision.

The limitation of this study was that surgical treatments were not standardized because of the wide variety of patients and the numerous surgeons involved. In addition, postoperative knee stability was assessed by a varus stress test in only 1 patient who was treated without LCL reconstruction; this was because no other patients exhibited instability; therefore, they were not specifically recalled to undergo varus stress tests for the study.

In conclusion, we treated 12 patients with aggressive benign or malignant proximal fibula tumors. We observed positive results, without peroneal nerve palsy, with regard to subjective symptoms and activities of daily life with resection of the fibular head. Four patients without LCL reconstruction did not exhibit instability, while 1 patient exhibited instability as determined by a varus stress test. Therefore, we recommend LCL reconstruction after fibular head resection. Aggressive benign tumors, such as GCTs located in the proximal fibula, should be treated with en bloc resection because of the high local recurrence rate.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language review.

References

- 1.Unni K.K., Inwards C.Y. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 2010. Dahlin's Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 10,165 Cases; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Japanese Orthopaedic Association . National Cancer Center; Tokyo: 2013. Musculoskeletal Tumor Committee, Bone Tumor Registry in Japan-2010. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaPrade F.R., Wentorf F. Diagnosis and treatment of posterolateral knee injuries. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2002;402:110–121. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaPrade F.R., Terry C.G. Injuries to the posterolateral aspect of the knee. Association of anatomic injury patterns with clinical instability. Am. J. Sport Med. 1997;25:433–438. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel P.M., Papagelopoulos J.P., Morrey E.M., Wenge E.D., Rose S.P., Sim H.F. Surgical management of 121 benign proximal fibula tumors. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010;468:3056–3062. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1464-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanazawa Y., Tsuchiya H., Nonomura A., Takazawa K., Yamamoto N., Tomita K. Intentional marginal excision of osteosarcoma of the proximal fibula to preserve limb function. J. Orthop. Sci. 2003;8:757–761. doi: 10.1007/s00776-003-0714-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Einoder A.P., Choong F.P. Tumors of the head of the fibula: good function after resection without ligament reconstruction in 6 patients. Acta Orthop. Scand. 2002;73:663–666. doi: 10.1080/000164702321039633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel P.M., Papagelopoulos J.P., Morrey E.M., Inwards Y.C., Wenger E.D., Rose S.P., Sim H.F. Malignant proximal fibular tumors: surgical management of 112 cases. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2012;94:e165. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mimata Y., Nishida J., Shiraishi H., Suzuki Y., Akasaka T., Oikawa S., Murakami K., Shimamura T. Two cases of chondrosarcoma occurred in the proximal fibula. Tohoku J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2011;55:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bickels J., Kollender Y., Pritsch T., Meller I., Malawer M.M. Knee stability after resection of the proximal fibula. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2006;454:198–201. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238781.19692.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]