Abstract

Hepatocarcinoma is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths around the world. Recently, a novel emerging nanosystem as anticancer therapeutic agents with intrinsic therapeutic properties has been widely used in various medical applications. In this study, surface decoration of functionalized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) by polyethylenimine (PEI) and paclitaxel (PTX) was synthesized. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of Ag@ PEI@PTX on cytotoxic and anticancer mechanism on HepG2 cells. The transmission electron microscope image and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay showed that Ag@PEI@PTX had satisfactory size distribution and high stability and selectivity between cancer and normal cells. Ag@PEI@PTX-induced HepG2 cell apoptosis was confirmed by accumulation of the sub-G1 cells population, translocation of phosphatidylserine, depletion of mitochondrial membrane potential, DNA fragmentation, caspase-3 activation, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage. Furthermore, Ag@PEI@PTX enhanced cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells and triggered intracellular reactive oxygen species; the signaling pathways of AKT, p53, and MAPK were activated to advance cell apoptosis. In conclusion, the results reveal that Ag@ PEI@PTX may provide useful information on Ag@PEI@PTX-induced HepG2 cell apoptosis and as appropriate candidate for chemotherapy of cancer.

Keywords: silver nanoparticles, polyethylenimine, paclitaxel, reactive oxygen species, apoptosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is considered as one of the most common primary liver cancers around the world and the second leading cause of cancer-associated mortality with 75,000 cases increasing annually.1–3 Unfortunately, the diagnosis of early-stage HCC is difficult and the long-term prognosis remains unsatisfactory without efficient early detection and surveillance strategies.4,5 Meanwhile, as most cases with HCC are metastatic or advanced at the time of diagnosis, the local therapies including liver transplantation and surgical excision are unsuitable.6,7 Furthermore, chemotherapeutic is generally ineffective against advanced HCC, which has high metastatic potential.8 Finally, most conventional cancer therapeutics have a relatively short half-life and poor permeability, which may influence curative effect.9 Therefore, it is urgent to develop a novel systemic chemotherapy for HCC in medicine.

Recently, nanobiotechnology plays an important role in cancer therapy.10,11 It improves the efficiency of drug delivery, reduces side effects of drug, and strengthens molecular targeting in biomedical applications.12–14 Nanomaterial is considered to be a promising solution to overcome the above problems with the peculiar properties, including high stability; smart, controllable morphology; thermal properties; soluble behaviors in aqueous solution; and surface functionalization.15 Among them, metal nano-particles, especially silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), are considered as one of the nanomaterials with the highest degree of commercialization.16 Furthermore, AgNPs have gained wide attention due to its potent activity, including antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, antiangiogenic, and anti-inflammatory.17,18 In addition, several studies reported that AgNPs induced cell apoptosis in cancer cells but not in normal cells, as the cancer cells are more acidic, which is useful for the release of silver ions from the AgNPs.18,19 As one of the most traditional polycationic polymers, polyethylenimine (PEI), can promote nanoparticles entering into the cells by improving its zeta potential.20 PEI-functionalized AgNPs were chosen to be as drug carrier in our study. Paclitaxel (PTX), a chemotherapeutic agent, is widely used against several types of solid tumors besides breast, ovarian, lung, colon, head, neck, and liver cancers.21–27 PTX disrupts the tubulin–microtubule equilibrium, which is different from conventional anticancer drugs affecting nucleic acid synthesis to induce cancer cell death.28,29 It is considered as an appropriate candidate for chemotherapy because PTX at low concentrations can exert antiangiogenic activity.30 However, the major problem for the clinical efficacy of PTX is compromised by its poor water solubility, low permeability, and serious adverse effects.31 Therefore, to improve the anticancer efficacy, Ag@PEI@PTX was synthesized by PEI-conjugated AgNPs to induce cancer cell apoptosis.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were considered as one of the key players in some physiological processes through the mechanisms of apoptosis and autophagy.32–37 ROS are generated in several cellular systems, such as plasma membrane, peroxisomes, cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum, and membranes of mitochondria.37 The imbalance between ROS generation and antioxidant system triggers oxidative stress, which is related to much pathology, including cancer, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and other diseases.38,39 Many reports have demonstrated the relationship of AgNPs-mediated cytotoxic and oxidative stress, but the anticancer mechanisms of AgNPs have remained poorly understood.40,41 Thus, Ag@PEI@PTX was synthesized as a novel chemotherapeutic agent to achieve HepG2 apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Materials

The HepG2 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC®, CCL-136™). LO2 cells (normal human liver cells line) were provided from Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium and fetal bovine serum purchased from Gibco were used for cell culture. PTX, AgNO3, vitamin C, branched PEI, propidium iodide (PI), 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate, 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were all obtained from Sigma. Capase-3, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), H2X, P-p53, P53, TAKT, T-p38, and β-actin monoclonal antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit, Annexin-V-FLUOS staining kit, caspase-3 activity assay kit, and BCA protein assay kit were acquired from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China).

Preparation and characterization of Ag@PEI@PTX

AgNPs were prepared as follows:42 briefly, 0.1 mL of vitamin C solution (400 µg/mL) was added dropwise into 4 mL AgNO3 (400 µg/mL) under magnetic stirring for 2 h at room temperature. Then, AgNPs was mixed in 3.792 mg PEI and 0.32 mL of 6 mg/mL PTX at a final volume of 4 mL with Milli-Q water. The Ag@PEI@PTX complex was purified by dialysis for overnight. Ag@PEI@PTX nanoparticles were sonicated and then filtered through a 0.2-µm pore size filter. The concentration of AgNPs was measured by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy. AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX were characterized by transmission electron microscope (TEM, H-7650; Hitachi). The particle zeta potential and size distribution were determined by Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Limited) particle analyzer.

Cell culture and viability assay

The HepG2 and LO2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with an antibiotic, fetal bovine serum (10%), 100 units per mL penicillin, and 50 units per mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. The cells, proliferative inhibition of Ag@ PEI@PTX nanoparticles was measured using MTT assay as previously described.43 Briefly, the cells were incubated with different treatments of control, AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@ PEI@PTX at a density of 4×104 cells per well at 37°C for 24 h. Then, 20 µL of MTT solution was added to each well (5 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and incubated for 5 h. After that, the medium containing MTT was aspirated off and replaced with dimethyl sulfoxide (150 µL/well) to dissolve the dark blue formazan salt formed in surviving cells. The color intensity of the formazan solution was read at 570 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (SpectroAmax™ 250). The cell viability was expressed as percentage of MTT reduction relative to the absorbance of control.

Mitochondrial membrane potential measurement (ΔΨm)

JC-1 was used to assess the change of mitochondrial membrane potential in HepG2 cells exposed to Ag@PEI@PTX as previously reported.44 The cells cultured in 6-well plates were released by trypsinization, resuspended in PBS buffer with 10 µg/mL JC-1, and then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. JC-1 fluorescence was measured using a single excitation wavelength (485 nm) with dual emission (shift from green at 530 nm to red at 590 nm). The percentage of the green fluorescence from JC-1 monomers was used to represent the cells that lost ΔΨm.

Annexin-V/PI double-staining assay

Translocation of phosphatidylserine in HepG2 treated with Ag@PEI@PTX was detected by Annexin-V-fluorescein isothiocyanate staining and PI kit as previously described.45 In brief, the cells were treated with Ag@PEI@PTX for 24 h and stained with Annexin-V/PI for 30 min, followed by flow cytometric analysis.

Cell-cycle analysis

The effect of Ag@PEI@PTX on cell-cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry as previously reported.46 The cells incubated with Ag@PEI@PTX were collected and centrifuged at a speed of 1,500 rpm for 10 min. Then, the harvested cells were fixed with chilled 70% ethanol at −20°C overnight. The fixed cells were stained by PI (50 µg/mL) at 37°C for 30 min in darkness. DNA histogram was used to express the proportion of cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases. The apoptotic cells with hypodiploid DNA content were detected by quantifying in the sub-G1 peak.

TUNEL and DAPI staining

DNA fragmentation induced by Ag@PEI@PTX was detected with fluorescence staining by the TUNEL apoptosis detected kit following the manufacturer’s protocol.47 Briefly, HepG2 cells in chamber slides were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Then, the HepG2 cells were labeled with TUNEL reaction mixture for 1 h at 37°C. For nuclear staining, cells were with incubated with 1 µg/mL of DAPI for 30 min at 37°C. Finally, the stained cells were washed with PBS and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i).

Caspase-3 activity

As described in our previous paper, caspase-3 activity was determined by fluorometric method.48 Harvested cell pellets were suspended in cell lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 1 h. Caspase activity was determined by fluorescence intensity using caspase-3 substrates (Ac-DEVD-AMC) with an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm, respectively.

Determination of ROS generation

ROS accumulation induced by Ag@PEI@PTX-treated HepG2 cells were estimated by staining cells with DCF fluorescence assay as previously described.42 In brief, HepG2 cells were harvested and suspended in PBS containing 10 µM of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate for 30 min. ROS generation was indicated by green florescence, which was measured using a microplate reader with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission wavelength of 525 nm, respectively.

Western blot analysis

To examine the expression levels of various intracellular proteins in HepG2 cells treated with Ag@PEI@PTX, western blotting was performed as previously reported.49,50 Briefly, HepG2 cells treated with Ag@PEI@PTX were incubated with lysis buffer to obtain total cellular proteins, which were then isolated in a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Later, the polyvinylidene fluoride membranes were incubated with primary antibody and appropriate secondary antibody. The proteins were visualized using ECL chemiluminescence solution and examined on the X-ray film.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed at least for three times. All data were processed using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The difference between three or more groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons. Differences between two groups were evaluated by two-tailed Student’s t-test. A probability of *P<0.05 or **P<0.01 indicates statistically significant values.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of Ag@PEI@PTX

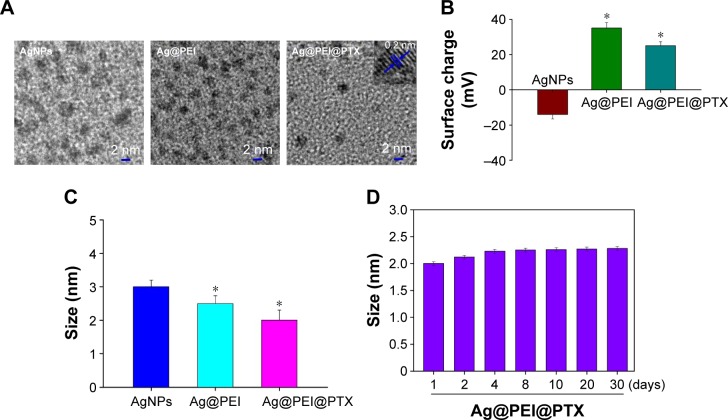

In this study, a simple method to prepare PEI-modified AgNPs loaded with PTX (Ag@PEI@PTX) to improve anticancer efficacy was demonstrated. The morphology and stability of Ag@PEI@PTX was detected and analyzed using various methods. TEM images showed that Ag@ PEI@PTX presented a spherical and monodisperse particles (Figure 1A). The zeta potential of AgNPs was −17.8 mV and increased to 23 mV after capping with PEI and PTX (Figure 1B), which indicated that Ag@PEI@PTX with positive charge was easier to cross into the cell membrane. Ag@PEI@PTX presented high uniformity with a minimum diameter of 2 nm (Figure 1C). Furthermore, the size distribution of Ag@PEI@PTX revealed that the decorated AgNPs was stable at least 30 days (Figure 1D), which also indicated that Ag@PEI@PTX was highly stable in aqueous solutions. Taken together, with the property of smart, stable, and zeta potential positive charge, Ag@PEI@PTX could easily enter into cells.

Figure 1.

Characterization of Ag@PEI@PTX.

Notes: (A) Transmission electron microscopy imaging of AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX. Inset is a TEM image of an individual particle, lattice fringe. (B) Zeta potential of AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX. (C) Particle size of AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX. (D) Stability of Ag@PEI@PTX in aqueous solutions. Bars with different characters are statistically different at P<0.05 (*) level.

Abbreviations: AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; PEI, polyethylenimine; PTX, paclitaxel.

In vitro cytoxicity of Ag@PEI@PTX

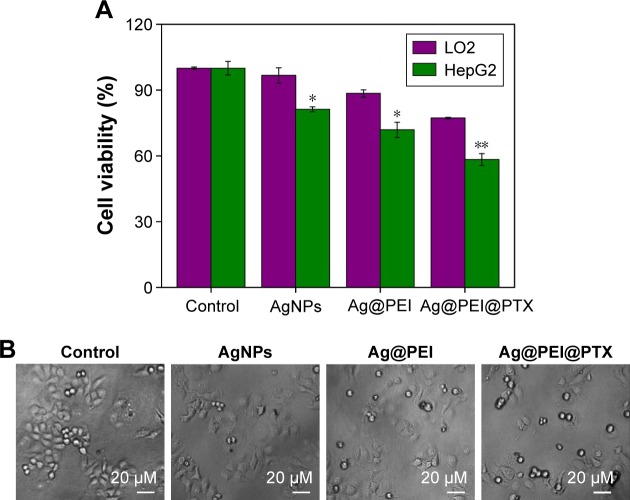

To determine the cell viability and reflect their growth states, the anticancer activity of AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@ PTX was measured by MTT assay. As shown in Figure 2A, the cell viability of HepG2 was dramatically lower than LO2 cells when treated with AgNPs (81.27% vs 96.67%), Ag@PEI (71.86% vs 88.45%), and Ag@PEI@PTX (77.21% vs 58.32%). Compared with AgNPs and Ag@PEI, Ag@ PEI@PTX significantly inhibited the growth of HepG2 cells and exhibited low cytotoxic toward LO2 cells. As shown in Figure 2B, the effects of AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@ PTX on the growth of HepG2 cells were further confirmed. After being treated with AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@ PTX, the cell numbers reduced with cells rounding and cytoplasm shrinkage. The results suggested that Ag@PEI@ PTX effectively inhibited the proliferation of HepG2 cells and induced cancer cell death.

Figure 2.

Effects of AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX on the growth of HepG2.

Notes: (A) Cell viability was evaluated after treated with AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX for 24 h by MTT assay. The concentration of AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX was 2.5 µg/mL. (B) Morphological changes in HepG2 cells with different treatments. Bars with different characters are statistically different at P<0.05 (*) or P<0.01 (**) level.

Abbreviations: NPs, nanoparticles; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; PEI, polyethylenimine; PTX, paclitaxel.

Depletion of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

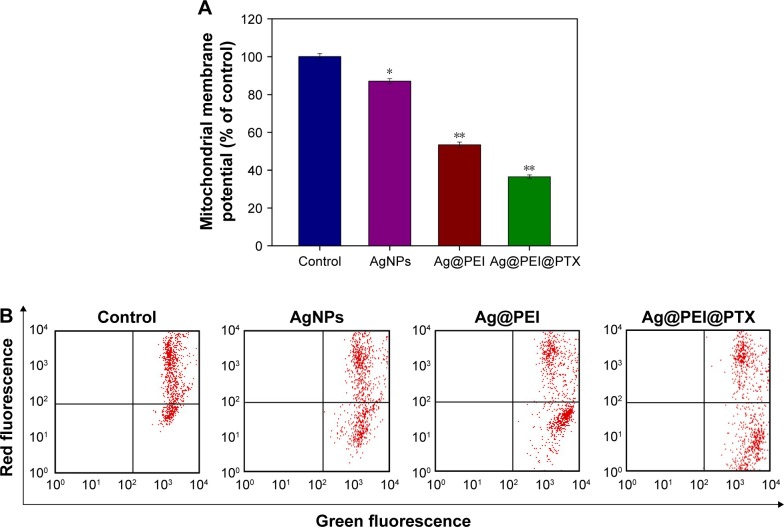

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) by flow cytometric analysis was used to investigate the initiation of apoptosis.44 As shown in Figure 3A, compared with the control group, the mitochondrial membrane potential was reduced significantly to 87.1%, 53.4%, and 36.5% for AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX, respectively. As shown in Figure 3B, representative scattergrams for red-FL2-H fluorescence indicated an intact mitochondrial membrane potential and green-FL1-H fluorescence indicated the loss of membrane potential. Treatment of HepG2 cells resulted in elevation of mitochondria depolarization, which is indicated by the shift of fluorescence from red to green. These results demonstrated that Ag@PEI@PTX triggered HepG2 cells apoptosis through the induction of mitochondrial dysfunction.

Figure 3.

Depletion of mitochondrial membrane potential induced by AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX.

Notes: (A) The percentage of mitochondrial membrane potential. (B) Mitochondrial membrane potential of HepG2 exposed to AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX. Bars with different characters are statistically different at P<0.05 (*) or P<0.01 (**) level.

Abbreviations: AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; PEI, polyethylenimine; PTX, paclitaxel.

Translocation of phosphatidylserine induced by Ag@PEI@PTX

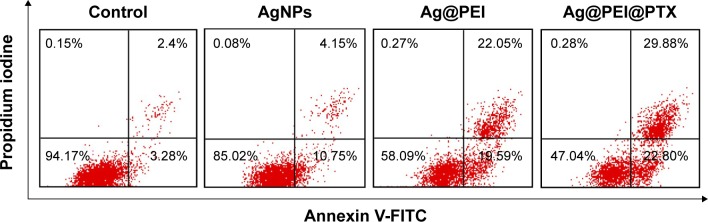

The translocation of phosphatidylserine to the outer membrane is an important step in the apoptosis of HepG2 cells.44 Annexin-V/PI double-staining assay was also used to characterize the apoptotic cells death induced by Ag@ PEI@PTX. As shown in Figure 4, dot plot results of HepG2 cell treated groups showed the presence of both early and late apoptotic cells. HepG2 cells treated with Ag@PEI@ PTX revealed the increased cell number of apoptosis. Taken together, the results indicated that Ag@PEI@PTX inhibited HepG2 cells proliferation mainly through apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Translocation of phosphatidylserine induced by AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX in HepG2 cells.

Note: The upper right quadrant indicated cells in the early stage of apoptosis and lower right shows cells in the late stage of apoptosis or necrosis.

Abbreviations: AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PEI, polyethylenimine; PTX, paclitaxel.

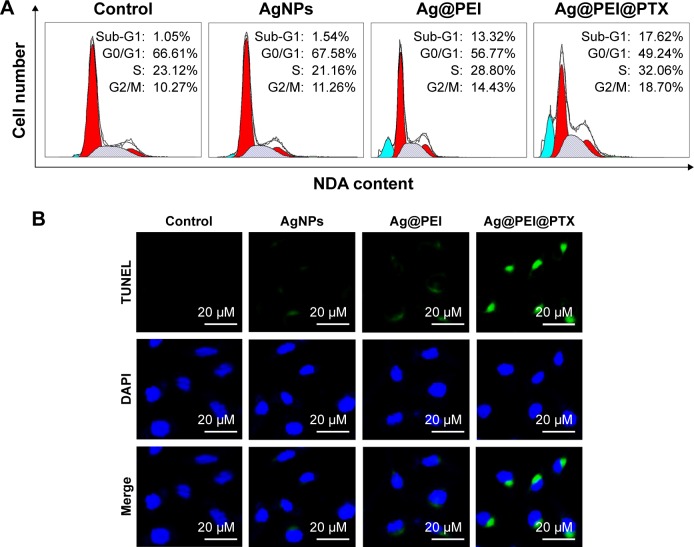

Ag@PEI@PTX induced HepG2 cell apoptosis

Apoptosis was one of the most crucial mechanisms accounting for the anticancer action.44 In this study, PI-flow cytometric analysis was used to investigate whether apoptosis was involved in the cell death induced by AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX. As shown in Figure 5A, compared with different treatments, the sub-G1 apoptotic cell population of Ag@PEI@PTX was significantly increased in the DNA histogram. For instance, the exposure of HepG2 cells to different treatments of control, AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@ PEI@PTX significantly increased in apoptotic population from 1.05% to 17.62%, while no significant change in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases was observed. DNA fragmentation is an important biochemical hallmark of cell apoptosis. The induction of apoptosis was further confirmed by TUNEL enzymatic labeling and DAPI co-staining assay. As shown in Figure 5B, HepG2 cells exhibited typical apoptotic features with Ag@PEI@PTX, such as DNA fragmentation and nuclear condensation. These results demonstrated that Ag@ PEI@PTX induced HepG2 cell apoptosis.

Figure 5.

Ag@PEI@PTX-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells.

Notes: (A) The cell-cycle distribution with different treatments was analyzed by quantifying DNA content using flow cytometric analysis. (B) Representative photomicrographs of DNA fragmentation and nuclear condensation as detected by TUNEL–DAPI co-staining assay.

Abbreviations: AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; DAPI, 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; TUNEL, terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

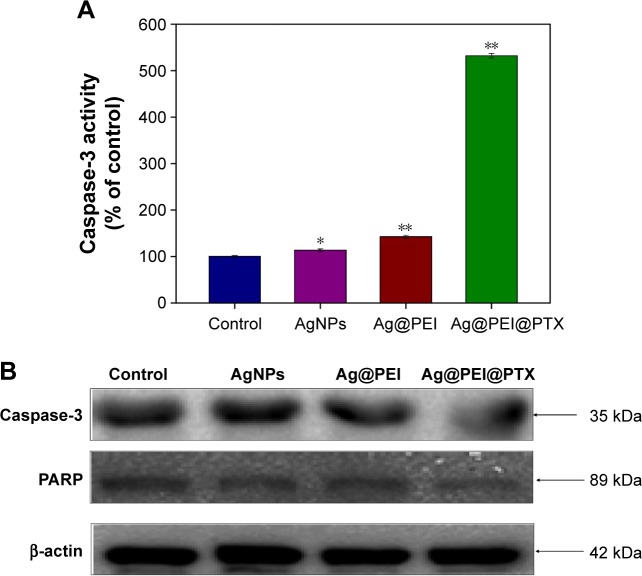

Induction of caspase-mediated PARP cleavage by Ag@PEI@PTX

Caspase-3 has been considered as the primary executioner of apoptosis, as it is responsible for the cleavage of many proteins and caspase involved in programmed cells death. PARP, which is one of the main cleavage targets of caspase-3, is downstream of caspase family proteins in apoptosis pathways.

Caspase-3 and the subsequent cleavage of PARP were examined by western blotting to evaluate their involvement and contribution to cell apoptosis. As shown in Figure 6A, compared with the control group, AgNPs, and Ag@PEI, treatments of HepG2 cells with Ag@PEI@PTX significantly increased the activity of caspase-3. As shown in Figure 6B, the expression level of caspase-3 and PARP was downregulated with different treatments. The results show that Ag@PEI@PTX significantly strengthened the activation of caspase-3 and the cleavage of downstream effect PARP. Taken together, these results reveal that the nanosystem significantly inhibits cancer cell growth by inducing apoptosis.

Figure 6.

Caspase-3 and PARP-mediated apoptosis induced by Ag@PEI@PTX in HepG2 cells.

Notes: (A) HepG2 cells treated with Ag@PEI@PTX and caspase-3 activity were analyzed by synthetic fluorogenic substrate. (B) The expression of PARP and caspase-3 by Western blot; β-actin was used as the loading control. Bars with different characters are statistically different at P<0.05 (*) or P<0.01 (**) level.

Abbreviations: AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase.

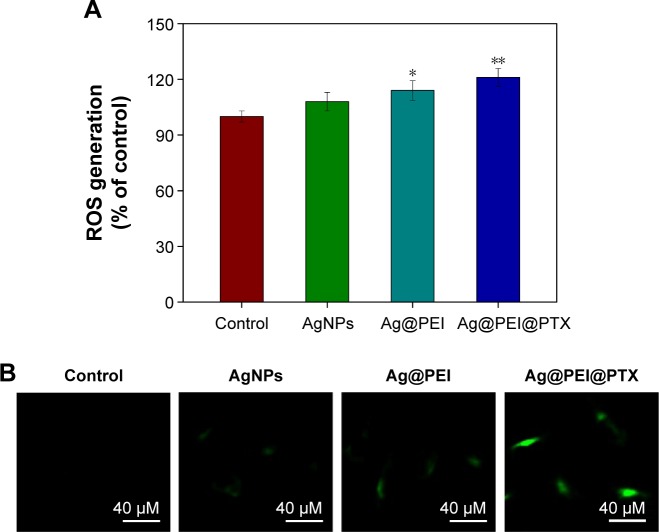

Induction of ROS generation by Ag@PEI@PTX

ROS was considered as an important regulator of cell apoptosis, especially that induced by anticancer drugs. Variety of factors can cause damage to the structure and function of mitochondria and further induce cell apoptosis. Mitochondrium is a major place to produce intracellular ROS.51 To investigate whether Ag@PEI@PTX could trigger ROS-mediated apoptosis, the intracellular ROS level was determined by DCF fluorescence assay. As shown in Figure 7A, compared with control group, AgNPs, and Ag@PEI, the ROS generation of HepG2 cells increased significantly after treatment with Ag@PEI@PTX. As shown in Figure 7B, the fluorescent intensity of DCF in HepG2 cells exposure to Ag@PEI@PTX was the most strongest in treatment groups. These results indicate the involvement of ROS in the anticancer activity of Ag@PEI@PTX.

Figure 7.

ROS overproduction induced by Ag@PEI@PTX of HepG2 cells.

Notes: (A) Changes in intracellular ROS generation detected by measuring DCF fluorescence intensity. (B) HepG2 cells were incubated with 10 µM DCF-DA in PBS for 30 min and then treated with AgNPs, Ag@PEI, and Ag@PEI@PTX under microscope. Bars with different characters are statistically different at *P<0.05 or **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; DCF-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

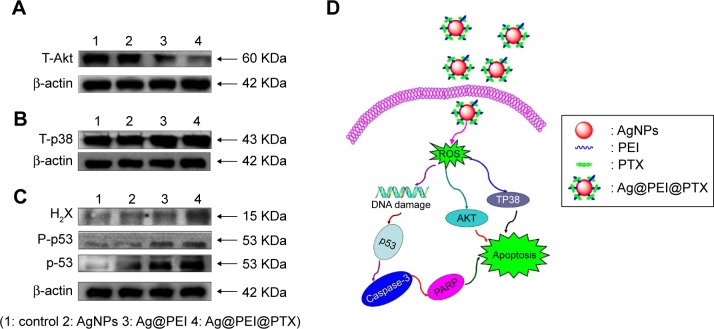

Activation of ROS-mediated signaling pathways by Ag@PEI@PTX

The mechanism of apoptosis by Ag@PEI@PTX induced in HepG2 cells was further investigated. Intracellular ROS overproduction could trigger DNA damage and cause a series of different signaling pathways, such as p53, AKT, and MAPK signaling pathways. Due to the detection of ROS overproduction in cells exposed to Ag@PEI@PTX, western blotting was used to examine the effects on the ROS-mediated signaling pathway. As shown in Figure 8A, compared with AgNPs and Ag@PEI, the expression of total AKT was downregulated after treatment with Ag@PEI@ PTX. Meanwhile, as shown in Figure 8B, HepG2 cells treated with Ag@PEI@PTX effectively increased the expression of total proapoptotic kinase p38 in HepG2 cells. For the p53 signaling pathway, Ag@PEI@PTX significantly increased the expression levels of H2X, p-p53, and total p53 (Figure 8C). Taken together, these results reveal that nanosystem induces HepG2 cells apoptosis through regulation of ROS-mediated AKT, MAPK, and p53 signaling pathways (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Activation of intracellular apoptotic signaling pathways by Ag@PEI@PTX in HepG2 cells.

Notes: (A) Phosphorylation status expression levels of AKT pathways. (B) Phosphorylation status expression levels of T-p38 MAPK pathways. (C) Activation of p53 signaling pathway. (D) The signaling pathway of regulation of ROS-mediated p53, AKT, and MAPK signaling pathways. The expression of β-actin was measured as control.

Abbreviations: AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; PEI, polyethyleneimine; PTX, paclitaxel; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study demonstrated that PEI-modified AgNPs loaded with PTX were successfully fabricated. Ag@ PEI@PTX showed a dramatic cytotoxic effects of HepG2 cells, which enhanced the drug sensitivity and induced apoptosis of cancer cells rather than normal cells. Moreover, the underlying molecular mechanisms indicated that Ag@PEI@PTX activated caspase-3-mediated HepG2 cell apoptosis via ROS generation. Furthermore, our results revealed the apoptotic signaling pathway through ROS was triggered by the Ag@PEI@PTX in HepG2 cells, including AKT, MAPK, and p53 signaling pathways. Taken together, this study provides the possibility of using nanosystem to induce HepG2 cell apoptosis and offers a new strategy for potential cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2015M582366), the Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No: 2014A020212697), the Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (No: 201607010120), and the Guangzhou Medical Health Science and Technology Project (No: 20151A010051).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Scortegagna E, Jr, Karam AR, Sioshansi S, Bozorgzadeh A, Barry C, Hussain S. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence pattern following liver transplantation and a suggested surveillance algorithm. Clin Imaging. 2016;40(6):1131–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong Y, Zou JJ, Su S, et al. MicroRNA-218 and microRNA-520a inhibit cell proliferation by downregulating E2F2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(1):1016–1022. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong XL, Qin SK. Progress in systemic therapy of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroentero. 2016;22(29):6582–6594. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i29.6582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia HP, Chen JX, Shi M, Deivasigamani A, Ooi LL, Hui KM. The over-expression of survivin enhances the chemotherapeutic efficacy of YM155 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(8):5990–6000. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ling D, Xia H, Park W, et al. pH-sensitive nanoformulated triptolide as a targeted therapeutic strategy for hepatocellular carcinoma. ACS Nano. 2014;8(8):8027–8039. doi: 10.1021/nn502074x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thapa RK, Choi JY, Poudel BK, et al. Multilayer-coated liquid crystalline nanoparticles for effective sorafenib delivery to hepatocellular carcinoma. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(36):20360–20368. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b06203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rand D, Ortiz V, Liu YA, et al. Nanomaterials for X-ray imaging: gold nanoparticle enhancement of X-ray scatter imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nano Lett. 2011;11(7):2678–2683. doi: 10.1021/nl200858y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li JH, Sharkey CC, Huang DT, King MR. Nanobiotechnology for the therapeutic targeting of cancer cells in blood. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2015;8(1):137–150. doi: 10.1007/s12195-015-0381-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friberg S, Nystrom AM. NANOMEDICINE: Will it offer possibilities to overcome multiple drug resistance in cancer? J Nanobiotechnol. 2016;14:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12951-016-0172-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan B, Webster TJ, Roy AK. Cytoprotective effects of cerium and selenium nanoparticles on heat-shocked human dermal fibroblasts: an in vitro evaluation. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:1427–1433. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S104082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chauhan VP, Jain RK. Strategies for advancing cancer nanomedicine. Nat Mater. 2013;12(11):958–962. doi: 10.1038/nmat3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbai R, Mathiyalagan R, Markus J, et al. Green synthesis of multifunctional silver and gold nanoparticles from the oriental herbal adaptogen: Siberian ginseng. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:3131–3143. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S108549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassan CE, Webster TJ. The effect of red-allotrope selenium nanoparticles on head and neck squamous cell viability and growth. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:3641–3654. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S105173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang YZ, Fan Z, Shao L, et al. Nanobody-derived nanobiotechnology tool kits for diverse biomedical and biotechnology applications. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:3287–3302. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S107194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang XX, Li CM, Huang CZ. Curcumin modified silver nanoparticles for highly efficient inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Nanoscale. 2016;8(5):3040–3048. doi: 10.1039/c5nr07918g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Y, Du Z, Ma S, et al. Biosynthesis, antibacterial activity and anticancer effects against prostate cancer (PC-3) cells of silver nanoparticles using Dimocarpus longan lour. peel extract. Nanoscale Res lett. 2016;11(1):300. doi: 10.1186/s11671-016-1511-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeong JK, Gurunathan S, Kang MH, et al. Hypoxia-mediated autophagic flux inhibits silver nanoparticle-triggered apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep21688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dziedzic A, Kubina R, Buldak RJ, Skonieczna M, Cholewa K. Silver nanoparticles exhibit the dose-dependent anti-proliferative effect against human squamous carcinoma cells attenuated in the presence of berberine. Molecules. 2016;21(3):365. doi: 10.3390/molecules21030365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li YH, Lin ZF, Zhao MQ, et al. Multifunctional selenium nanoparticles as carriers of HSP70 siRNA to induce apoptosis of HepG2 cells. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:3065–3076. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S109822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu YJ, Zhang B, Yan B. Enabling anticancer therapeutics by nanoparticle carriers: the delivery of paclitaxel. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(7):4395–4413. doi: 10.3390/ijms12074395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye J, Xia X, Dong W, et al. Cellular uptake mechanism and comparative evaluation of antineoplastic effects of paclitaxel-cholesterol lipid emulsion on triple-negative and non-triple-negative breast cancer cell lines. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:4125–4140. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S113638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voloshin T, Munster M, Blatt R, et al. Alternating electric fields (TTFields) in combination with paclitaxel are therapeutically effective against ovarian cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Int Cancer. 2016;139(12):2850–2858. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yue T, Zheng X, Dou Y, et al. Interleukin 12 shows a better curative effect on lung cancer than paclitaxel and cisplatin doublet chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:665. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2701-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barker HE, Patel R, McLaughlin M, et al. CHK1 inhibition radiosensitizes head and neck cancers to paclitaxel-based chemoradiotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15(9):2042–2054. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon-Gracia L, Hunt H, Scodeller P, et al. iRGD peptide conjugation potentiates intraperitoneal tumor delivery of paclitaxel with polymersomes. Biomaterials. 2016;104:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanei T, Leonard F, Liu XW, et al. Redirecting transport of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel to macrophages enhances therapeutic efficacy against liver metastases. Cancer Res. 2016;76(2):429–439. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horinouchi H, Yamamoto N, Nokihara H, et al. A phase 1 study of linifanib in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel as first-line treatment of Japanese patients with advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 2014;74(1):37–43. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu JH, Hu SL, Shen GD, Shen G. Tumor suppressor genes and their underlying interactions in paclitaxel resistance in cancer therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2016;16:13. doi: 10.1186/s12935-016-0290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parayath NN, Nehoff H, Norton SE, et al. Styrene maleic acid- encapsulated paclitaxel micelles: antitumor activity and toxicity studies following oral administration in a murine orthotopic colon cancer model. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:3979–3991. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S110251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He ZJ, Wan XM, Schulz A, et al. A high capacity polymeric micelle of paclitaxel: implication of high dose drug therapy to safety and in vivo anti-cancer activity. Biomaterials. 2016;101:296–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi EO, Park C, Hwang HJ, et al. Baicalein induces apoptosis via ROS-dependent activation of caspases in human bladder cancer 5637 cells. Int J Oncol. 2016;49(3):1009–1018. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu K, Zhao Q, Liu P, et al. ATG3-dependent autophagy mediates mitochondrial homeostasis in pluripotency acquirement and maintenance. Autophagy. 2016;12(11):1–9. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1212786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang XF, Gurunathan S. Combination of salinomycin and silver nanoparticles enhances apoptosis and autophagy in human ovarian cancer cells: an effective anticancer therapy. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:3655–3675. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S111279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khojah HM, Ahmed S, Abdel-Rahman MS, Hamza AB. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in patients with rheumatoid arthritis as potential biomarkers for disease activity and the role of antioxidants. Free Radic Bio Med. 2016;97:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farah MA, Ali MA, Chen SM, et al. Silver nanoparticles synthesized from Adenium obesum leaf extract induced DNA damage, apoptosis and autophagy via generation of reactive oxygen species. Colloid Surface B Biointerfaces. 2016;141:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Meo S, Reed TT, Venditti P, Victor VM. Role of ROS and RNS sources in physiological and pathological conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:1245049. doi: 10.1155/2016/1245049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang JX, Wang XL, Vikash V, et al. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:4350965. doi: 10.1155/2016/4350965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giacco F, Du XL, Carratu A, et al. GLP-1 cleavage product reverses persistent ROS generation after transient hyperglycemia by disrupting an ROS-generating feedback loop. Diabetes. 2015;64(9):3273–3284. doi: 10.2337/db15-0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee MJ, Lee SJ, Yun SJ, et al. Silver nanoparticles affect glucose metabolism in hepatoma cells through production of reactive oxygen species. Int J Nanomed. 2016;11:55–68. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S94907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun C, Yin NY, Wen RX, et al. Silver nanoparticles induced neurotoxicity through oxidative stress in rat cerebral astrocytes is distinct from the effects of silver ions. Neurotoxicology. 2016;52:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu B, Li Y, Lin Z, et al. Silver nanoparticles induce HePG-2 cells apoptosis through ROS-mediated signaling pathways. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2016;11(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s11671-016-1419-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.You YY, Hu H, He LZ, Chen T. Differential effects of polymer-surface decoration on drug delivery, cellular retention, and action mechanisms of functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Chem Asian J. 2015;10(12):2743–2753. doi: 10.1002/asia.201500769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang YB, Li XL, Huang Z, Zheng W, Fan C, Chen T. Enhancement of cell permeabilization apoptosis-inducing activity of selenium nanoparticles by ATP surface decoration. Nanomedicine. 2013;9(1):74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu HL, Li XL, Liu W, et al. Surface decoration of selenium nanoparticles by mushroom polysaccharides-protein complexes to achieve enhanced cellular uptake and antiproliferative activity. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(19):9602–9610. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li YH, Li XL, Zheng WJ, Fan C, Chen T. Functionalized selenium nanoparticles with nephroprotective activity, the important roles of ROS-mediated signaling pathways. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1(46):6365–6372. doi: 10.1039/c3tb21168a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li YH, Li XL, Wong YS, et al. The reversal of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by selenium nanoparticles functionalized with 11-mercapto-1-undecanol by inhibition of ROS-mediated apoptosis. Biomaterials. 2011;32(34):9068–9076. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu W, Li XL, Wong YS, et al. Selenium nanoparticles as a carrier of 5-Fluorouracil to achieve anticancer synergism. ACS Nano. 2012;6(8):6578–6591. doi: 10.1021/nn202452c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang YY, He LZ, Liu W, et al. Selective cellular uptake and induction of apoptosis of cancer-targeted selenium nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2013;34(29):7106–7116. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Lin Z, Zhao M, et al. Silver nanoparticle based codelivery of oseltamivir to inhibit the activity of the H1N1 influenza virus through ROS-mediated signaling pathways. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(37):24385–24393. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b06613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen XF, Song MJ, Zhang B, Zhang Y. Reactive oxygen species regulate T cell immune response in the tumor microenvironment. Oxid Med Cell longev. 2016;2016:1580967. doi: 10.1155/2016/1580967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]