Abstract

Exosomes mediate intercellular microRNA delivery between hepatic stellate cells (HSC), the principal fibrosis-producing cells in the liver. The purpose of this study was to identify receptors on HSC for HSC-derived exosomes, which bind to HSC rather than to hepatocytes. Our findings indicate that exosome binding to HSC is blocked by treating HSC with RGD, EDTA, integrin αv or β1 siRNAs, integrin αvβ3 or α5β1 neutralizing antibodies, heparin, or sodium chlorate. Furthermore, exosome cargo delivery and exosome-regulated functions in HSC, including expression of fibrosis- or activation-associated genes and/or miR-214 target gene regulation, are dependent on cellular integrin αvβ3, integrin α5β1, or heparan-sulfate proteolgycans (HSPG). Thus, integrins and HSPG mediate the binding of HSC-derived exosomes to HSC as well as the delivery and intracellular action of the exosomal payload.

Keywords: microvesicle, hepatic fibrosis, fibrogenesis, microRNA, CCN2/CTGF

Introduction

Hepatic stellate cells (HSC) account for 3-5% of the cells in the liver and, under normal circumstances, are a quiescent cell type that plays a role in vitamin A storage and regulation of vascular tone [1]. During liver injury, HSC undergo an activation process that results in important alterations in their phenotype and function that are central to wound healing, including enhanced proliferation, migration, increased contractility due to expression of α smooth muscle actin (αSMA), and production of matrix proteins (collagen) [2]. In acute injury, this activation is transient and results in the deposition of a provisional matrix scaffold to support hepatocyte proliferation and repopulation. Chronic liver injury results in a perpetuation of the activated HSC phenotype resulting in unabated collagen production, causing fibrous scar material to be deposited which, over time, can seriously impede normal liver function [3]. Fibrogenic pathways in activated HSC are mediated by transforming growth factor-beta or connective tissue growth factor (CCN2; also known as CTGF) which are produced by activated HSC as well as by other liver cell types after injury [1-6]. Pathways of fibrogenesis in HSC have become the focus of a concerted effort to understand the underlying mechanisms involved and have led to the identification of rational targets for therapeutic intervention [7-10]; the importance of these advances is underscored by the paucity of approved anti-fibrotic drugs despite the prevalence of liver fibrosis, which affects millions of people globally.

CCN2 production in quiescent HSC is directly suppressed by the binding to the CCN2 3’ untranslated region (3’-UTR) of microRNA (miR) −214 or miR-199a-5p each of which is transcribed downstream of the Twist1 transcription factor [11-13]. This inhibitory Twist1-miR-214-miR-199a-5p pathway is suppressed in activated HSC, allowing CCN2 to be produced and to drive fibrogenesis in the cells. Twist1 or miR-214/199a-5p may also be exported from HSC in exosomes [11-13], membranous nanovesicles that arise by inward budding of multivesicular bodies and which are released extracellularly when multivesicular bodies fuse internally with the plasma membrane. Exosomes traverse the intercellular space and may be taken up by neighboring cells, including HSC themselves [14]. Exosomes contain a complex mixture of miRs, mRNAs and proteins that reflect the transcriptional and/or translational activity of the donor cell and which may cause epigenetic re-programing and phenotypic alterations in recipient cells [14-16]. Exosomes from quiescent HSC are intercellularly shuttled to activated HSC in which the activated phenotype is then suppressed [12, 13, 17]. This is due, in part, to exosomal delivery of Twist1 or miR-214/199a-5p that cause, respectively, enhanced expression of miR-214 or reduced expression of CCN2, the net effect of which is to dampen CCN2-dependent fibrogenic pathways in activated HSC [12, 13, 17]. Similarly, CCN2 can also be exosomally shuttled from activated HSC and delivered to other HSC recipients in which it is biologically active and can drive fibrogenesis [18]. Collectively, the participation of neighboring HSC in exosomal communication networks represents a mechanism by which fibrogenic signaling is fine-tuned and up- or down-regulated according to the differential activation status of recipient and donor cells. Despite these advances, exosomes represent a largely unexplored component of fibrogenic signaling that requires detailed study.

Exosomal cargo transfer between HSC occurs as a result of the direct binding of exosomes to the surface of the recipient HSC. An improved understanding of the molecular basis for exosome interactions with target HSC may provide unique opportunities to exploit this natural delivery mechanism for improving efficacy or targeting of anti-fibrotic agents. The purpose of these studies was to identify cell surface molecules that mediate functional binding of HSC-derived exosomes to recipient HSC.

Materials and Methods

Animal procedures

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Columbus, OH). Male FVB mice (6–8 weeks) (n=10) were injected i.p. three times each week for 5 weeks with either 30 μl of vegetable oil or a mixture of 0.5 μl carbon tetrachloride (CCl4, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in 29.5 μl of vegetable oil. Mice were then injected via the tail vein with 40μg of PKH26-labeled HSC-derived exosomes and four hours later, animals were sacrificed. Livers lobes were either perfused for subsequent isolation of HSC or hepatocytes, or immediately harvested along with the other major body organs for fluorescence imaging using a Xenogen IVIS 200 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Primary mouse HSC or hepatocytes

Livers from exosome-treated mice were perfused in situ and then subjected to either collagenase digestion for isolation of hepatocytes [19] or pronase/collagenase digestion and buoyant-density centrifugation for isolation of HSC [17]. Hepatocytes or HSC were maintained in, respectively, complete William E medium (Gibco, Billings, MT) or DMEM/F12/10% FBS for 24-hrs and then analyzed by confocal microscopy for the presence of PKH26.

For in vitro exosome binding studies, hepatocytes or HSC were isolated from Swiss Webster mice as described above and maintained in primary culture for up to, respectively, 72 hrs or passage 6 (P6; 1:3 split every 5 days). Binding assays were performed on cells seeded at 5000 cells/well in 8-well multi-chamber slides (Falcon, Caroll, OH).

Purification of HSC-derived exosomes

Exosomes were removed from FBS by serial ultracentrifugation [20] prior to using it for HSC culture. Exosomes were isolated from conditioned medium of P6 HSC using standardized steps of low and ultra-speed centrifugation [20]. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NanosightTM, Malvern Instruments, Westborough, MA) was used to determine exosome size and frequency. Exosomes were further evaluated for morphology and size using a Tecnai G2 F20 cryogenic transmission electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, Oregon) as described [17]. For some experiments, HSC were treated with 500nM SYTO RNASelect™ Green Fluorescent Cell Stain (Thermo Fisher) for 12 hrs and then incubated in fresh medium (exosome-free) for 48 hrs prior to exosome isolation. For other experiments, miR-199a-5p mimic (Qiagen) was labeled with Cy3 dye using a Label II® miRNA labeling kit (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison WI) and then transfected into exosomes by electroporation using a Nucleofector kit (Lonza, Koln, Germany); exosomes were then re-purified using a PureExo kit (101Bio, Palo Alto, CA).

Exosome binding assays

Exosomes from control or SYTO-RNA-labeled HSC or that contained Cy3-miR-199a-5p were labeled for 1 hr with 4 μM of the fluorescent lipophilic membrane dyes PKH26 or PKH67, according the manufacturer’s specifications (Sigma-Aldrich). Exosomes (0- 4 μg/ml) or free Cy3-labeled miR-199a-5p (1 μM) were added for up to 48 hrs to primary mouse HSC or hepatocytes which were then washed in PBS and imaged using a confocal microscope (Zeiss, Obercochen, Germany) or lysed in lysis buffer (Boston Bioproducts, Ashland, MA) and measured at 590/540 nm using a Spectra Max® M2 microplate reader (VWR, Atlanta, GA) to assess levels of PKH26 flourescence. Prior to exosome addition in some experiments, HSC were stained with PKH67 (Sigma-Aldrich) and hepatocytes were stained with far red (Sigma-Aldrich). In some binding experiments, HSC were pre-treated or co-incubated with 0-100 μg/ml RGD or RGE tripeptides (American Peptide, Sunnyvale CA), 0-100 μM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich), 0-10 μM sodium chlorate (Sigma-Aldrich), 0-10 μM sodium sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich), 0-10 μg/ml rabbit anti-mouse integrin αvβ3 IgG (Bioss Inc, Woburn, MA), or 0-20 μg/ml rat anti-mouse integrin α5β1 IgG (Millipore, Temecula, CA) or 0-10 μg/ml rat anti-mouse integrin αM, (CD11b; Novus Biologicals Littleton CO). For antibody studies, non-immune IgG was used as a negative control.

Integrin knockdown

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) to mouse integrin αv or β1, or negative controls were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). To avoid off-target effects, the siRNA preparations consisted of 3 target-specific 20-25 nt siRNAs. Primary mouse HSC (105-106 cells) were transfected with 100nM siRNA by electroporation using a Nucleofector Kit (Lonza) and incubated for 12 hours in medium containing 10% FBS which was then replaced with fresh medium. Our previous data have shown a 40% transfection efficiency of siRNA in primary mouse HSC using this approach [12]. Integrin knockdown was confirmed by RT-PCR (see Table 1 for primer sequences) or Western blot analysis of cell lysates using anti-αvβ3 or anti-α5β1 with anti-β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) serving as a loading control [12, 13, 17]. Cells were then used for exosome binding analysis as described above.

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR

| Gene | Genbank accession number |

Sense primer | Anti-sense primer | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrin αv (mouse) |

NM_008402 | 5’-ACATCACCTGGGGCATTCAG-3’ | 5’-GTGAACTTGGAGCGGACAGA-3’ | 251 |

| Integrin β1 (mouse) |

NM_010578 | 5’-AATGTTTCAGTGCAGAGCC-3’ | 5’-TTGGGATGATGTCGGGAC-3’ | 254 |

| GAPDH (mouse) |

NM_002046 | 5’-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3’ | 5’-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3’ | 87 |

Regulation of CCN2-3’UTR by miR-214-enriched exosomes

The full-length 997bp 3’-UTR of mouse CCN2 was subcloned into a Fire-Ctx sensor lentivector (SBI, Mountain View, CA, USA), downstream of the Firefly luciferase reporter and cytotoxin (CTX) drug sensor genes as described [17]. Recipient HSC were transfected with parental or CCN2 3’-UTR vectors for 24 hrs prior to 1-hr incubation with RGD, IgG, anti-integrin αvβ3 or anti-integrin α5β1. Cells were then incubated for 24 hrs in the presence of exosomes isolated from Day 1 HSC which we previously showed are highly enriched in miR-214 which directly targets the CCN2 3’-UTR [17]. To control for transfection efficiency, cells were also transfected with 0.8 μg pRL-CMV vector (Promega, Madison WI, USA) containing Renilla luciferase reporter gene. Luciferase activity was measured in triplicate using an E1910 Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Renilla luciferase activity was used for normalization, and Firefly luciferase activity in exosome treated cells was compared to that in non-treated cells.

HSC co-culture system

One well of a 2-well micro-culture system (Ibidi Inc., Verona, WI, USA) [12, 13, 17] received exosome donor P6 HSC that had been transfected with 100nM pre-mir-214 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Some cells were cultured with 10 μM GW4869, an inhibitor of neutral sphingomyelinase 2 which is required for exosome biogenesis [21, 22]. After 12 hrs, the other well was seeded with P6 HSC transfected with parental miR-Selection Fire-Ctx lentivector or the same vector containing either wild type or mutant CCN2 3’-UTR lacking the miR-214 binding site [17]. After 12 hrs, direct communication between the cells was initiated and proceeded for 24hrs. In some experiments, 100 μg/ml heparin sulfate or 100 μg/ml chondroitin sulfate were included in the culture medium. Luciferase activity was measured in triplicate using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System. Firefly luciferase activity in pre-mir-21- transfected cells was compared to that in non-transfected cells, with Renilla luciferase activity used for normalization.

Cell adhesion assay

96-well non-tissue culture plates (Costar, Corning, NY) were coated with CCN2 and blocked with BSA prior to addition of 50 μl cell suspension (2.5 × 105 cells/ml) for 30 mins at 37 °C as described [23]. The added cells were primary mouse activated HSC (see above) or Day 9 primary mouse bone-marrow-derived macrophages that were obtained as described [24]. Prior to addition to the CCN2-coated wells, cells were pre-incubated for 30 mins with 10-20 ug/ml anti-integrin antibodies or non-immune IgG. Wells were washed three times with PBS and adherent cells were fixed with 10% formalin and quantified using CyQUANT GR dye [23].

Immunoctyochemistry

P6 HSC were treated for 36 hrs with or without exosomes (8 μg/ml) from D1-3 HSC in the presence or absence of anti-integrin αvβ3 or anti-integrin α5β1. Cells were fixed and incubated with NH1 anti-CCN2 IgY (5μg/ml [25]), anti-αSMA (1:100, Dako Cytomatio, Denmark) or anti-collagen α(1) (1:250, Abcam), followed by Alexa Fluor® 568 goat-anti chicken IgY, Alexa Fluor® 647 goat-anti mouse IgG, or Alexa Fluor® 488 goat-anti rabbit IgG, respectively. The cells were mounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium containing 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear stain (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and examined by confocal microscopy.

Heparin-affinity

100 μg HSC exosomes were added to 120 μl TSKgel heparin-5PW affinity beads (Tosoh BioScience LLC, King of Prussia, PA) in 200 μl PBS and mixed at 37oC for 1 hr. The beads were washed 3 times with 1 ml PBS and then split into 10 equal aliquots which were then mixed for 15 mins with 200 μl PBS containing 0.15 – 2.5M NaCl. The beads were collected by centrifugation, washed twice in 200 μl of their respective NaCl treatment, and then extracted into 20 μl 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer, with boiling for 5 mins. 18 μl of each sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot with anti-CD81 (Pro-Sci, Fort Collins, CO), using a chemiluminscent detection kit (Promega, Madison, WI) to visualize immunoreactive protein.

Statistical Analysis

Data from binding assays, RT-PCR, Western blots, cellular fluorescence or luciferase activity assays are reported as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed using Student's t-test and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Sigma plot 12.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Cellular binding of HSC-derived exosomes

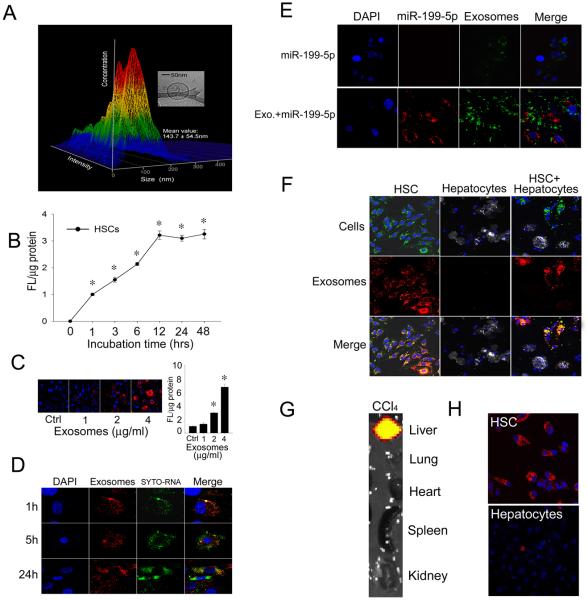

Exosomes isolated from P6 mouse HSC had a mean diameter of 144 nm as assessed by nanoparticle tracking analysis and were bi-membrane vesicles as assessed by cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (Fig 1A). These features were consistent with our earlier reports in which we demonstrated HSC exosomes to have a mean diameter of 140nm as assessed by dynamic light scattering, to carry a net charge of −26mV, and to express the exosome markers, CD9 and flotillin-1 [12, 17]. Exosomes were then labeled with the lipophilic fluorescent dye PKH26 so that their interactions with target cells could be visualized and quantified. As shown in Fig 1B, exosome binding to HSC was detected within 1 hr and reached maximal levels by 12hrs, with approximately 50% of binding occurring at 3-6 hrs. Exosomes from activated HSC demonstrated a dose-dependent binding to HSC recipient cells (Fig 1C) that resulted in delivery into the cells of their RNA cargo which became separated from the exosomal membrane components between 5 and 24 hrs after addition to the cells (Fig 1D). Uptake into recipient cells of exosomal miR-199a-5p similarly resulted in its distinct localization in the cells as compared to exosomal membrane stain and was effectively delivered into the cells, unlike free miR-199a-5p (Fig 1E). Exosomes bound strongly to primary cultures of HSC but not to hepatocytes, a phenomenon that was apparent in either individual cultures of each cell type, or in co-cultures of both cell types (Fig 1F). To verify that these findings faithfully reflected the preferential binding of exosomes to activated HSC in vivo, we analyzed the hepatic localization of systemically-injected exosomes. As shown in Fig 1G, within 4 hrs of tail vein injection, exosomes had accumulated mainly principally within CCl4-injured livers to the exclusion of the other organ systems. Examination of isolated liver cells from control or CCl4-treated mice revealed that the exosomes had bound to the HSC population, with essentially non-detectable binding to hepatocytes (Fig 1H). Based on their preferential binding to HSC both in vitro and in vivo, subsequent binding studies of HSC-derived exosomes were performed using activated HSC in vitro.

Figure 1. Characterization of HSC-derived exosomes and their preferential binding to HSC.

(A) Nanoparticle tracking analysis of exosomes secreted by P6 mouse HSC, showing a size range of 144 ± 55 nm. The inset shows the typical spherical bi-membrane characteristic of the exosomes as assessed by cryogenic transmission electron microscopy. (B) PKH26-stained exosomes from mouse HSC were incubated with primary mouse HSC for 0-48hrs. Cell associated fluorescence, assessed by spectrophotometry of cell lysates, was significant by 1hr and reached maximal levels by 12 hrs. n = 5, *p < 0.001 vs. 0hr; student’s t test. (C) Dose-dependent binding of exosomes to HSC over 24 hrs. The figure shows confocal microscopy of a representative experiment (left) and quantification of cell-associated fluoresence (right). n = 5 *p < 0.001 vs. Ctrl; student’s t test. “Ctrl’ is no added exosomes. (D) HSC were incubated with PKH26-labeled exosomes (red) containing SYTO-RNA (green) and the distribution of fluorescence in the cells was examined after 1, 5 or 24 hrs. Blue, DAPI. Data shown are representative of 3 replicates. (E) HSC were incubated for 24 hrs with Cy3-labeled miR-199a-5p (red) either free in solution or after electroporation into PKH67-labeled exosomes (green) . Data shown are representative of 3 replicates (F) PKH26-stained exosomes (red) from mouse HSC were incubated for 5 hrs with PKH67-stained primary mouse P6 HSC (green; 1st column), fluorescence far red-stained primary mouse hepatocytes (grey; 2nd column) or a co-culture of both cell types (3rd column). Blue, DAPI. Data shown are representative of 3 replicates (G) Distribution of PKH26-stained HSC-derived exosomes 4 h after i.v. injection in CCl4-treated mice. Data shown are representative of 5 animals (H) Representative fluorescence imaging of HSC or hepatocytes isolated from the mice in (G).

Role of integrins in exosome binding to HSC

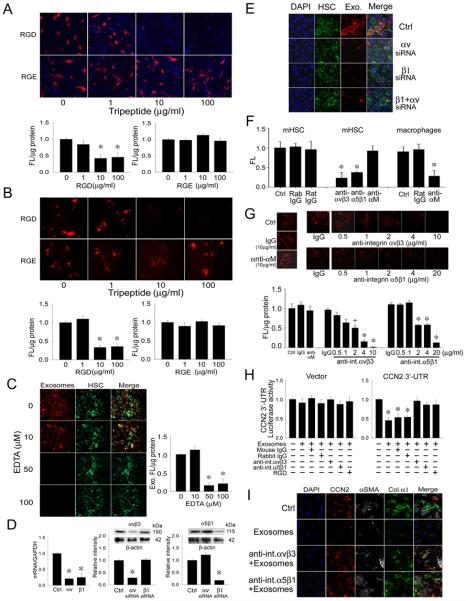

Binding of exosomes to HSC was dose-dependently blocked by inclusion of RGD in the incubation medium during a 12-hr binding experiment, the specificity of which was demonstrated by the inability of RGE to block exosome binding (Fig 2A). Pre-incubation of the target HSC for 1 hr with RGD, followed by extensive rinsing to remove excess peptide, also resulted in reduced exosome binding whereas pre-incubation with RGE was ineffective (Fig 2B). Since the RGD-sensitivity and specificity of exosome binding suggested a possible involvement of cell surface integrins, many of which require divalant cations for function, binding experiments were also performed in the presence of EDTA with the result that 50-100 μM EDTA inhibited exosome binding to HSC over 24 hrs (Fig 2C). To address the possible functional role of integrins αv or β1, HSC were transfected with siRNA to either or both subunits for 24 hrs prior to incubation with exosomes for the subsequent 24 hrs. This treatment, which resulted in decreased levels of αv or β1 mRNA of 78% or 75 % respectively and of αv or β1 protein levels of 75% or 90% respectively (Fig 2D), caused >95% of exosome binding to be blocked by the siRNAs, either individually or collectively (Fig 2E). Since we have previously documented the expression and function of integrins αvβ3 or α5β1 in activated HSC [23, 26], we examined their possible role in exosome binding. We first confirmed the functionality of neutralizing anti-integrin αvβ3 or anti-integrin α5β1 antibodies by demonstrating that they blocked adhesion of HSC to CCN2 as previously reported [23, 26] (Fig 2F). We next showed that these antibodies also caused a dose-dependent decrease in exosome binding, with >90% inhibition at 4 ug/ml anti-αvβ3 or 20 μg/ml anti-α5β1 (Fig 2G). The specificity of this outcome was confirmed using an antibody to integrin αM which neither blocked exosome binding to HSC (Fig 2G) nor HSC binding to CCN2 (Fig 2F) but nonetheless blocked macrophage adhesion to CCN2 (Fig 2F) consistent with the absence of integrin αM in quiescent or activated HSC [27] and the role of integrin αM as a CCN2 adhesion receptor for macrophages [28, 29]. Collectively, the antibody neutralization studies demonstrated a specific functional role for integrin αvβ3 and integrin α5β1 in mediating exosome binding to HSC.

Figure 2. Integrin-dependency of exosome interactions with HSC.

(A) PKH26-stained HSC-derived exosomes (red) were incubated with primary mouse HSC for 24hrs in the presence of RGD or RGE (0-100 μg/ml) in the incubation medium. Cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (20X) (upper, showing a representative experiment) or measured for cell-associated fluorescence by spectrophotometry of cell lysates (lower; n = 5, *p < 0.001 vs. 0 μg/ml RGD, student’s t test). (B) Mouse HSC were pre-incubated with RGD or RGE (0-100 μg/ml) for 1 hr and excess peptide was removed by extensive washing prior to addition of PKH26-stained HSC exosomes (red) for 24hrs. The cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (20X) (upper; showing a representative experiment) or by fluorescence intensity of cell lysates (lower; n = 5, *p < 0.001 vs. 0 μg/ml RGD, student’s t test. (C) PKH26-stained exosomes (red) were incubated with primary mouse HSC (green) for 24hrs with 0-100 μM EDTA. Cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (20X) (left; showing a representative experiment) or fluorescence in cell lysates was determined spectrophotometrically (right; n = 5, *p < 0.001 vs. 0 μM EDTA, student’s t test). (D) HSC were transfected for 24 hrs with integrin αv or β1 siRNA and analyzed for expression of αv or β1 mRNA by RT-PCR (left; n = 9, * p < 0.001 vs. Ctrl, student’s t test) or levels of their corresponding proteins by Western blot using anti-integrin αvβ3 (center) or anti-integrin α5β1 antibodies (right) for which β-actin was used a loading control (n = 9, *p <0.001 vs. Ctrl, student’s t test). “Ctrl” represents cells treated with a scrambled siRNA sequence. (E) Mouse HSC were transfected for 24 hrs with siRNA to the integrin αv or β1 subunits, either individually or together. Cells were then stained with PKH-67 (green) for 1 hr and incubated with PKH26-stained exosomes (red) for 24 hrs. Blue, DAPI. Data are representative of 3 experiments. (F) Adhesion of mouse HSC or macrophages to a CCN2 substrate after pre-incubation of the cells with neutralizing anti-integrin αvβ3 (10 μg/ml), anti-integrin α5β1 (20 μg/ml), anti-integrin αM (10 μg/ml), or their non-immune IgG counterparts (at the same respective dose). n = 5, *p < 0.001 vs. Ctrl, student’s t test. (G) Mouse HSC were pre-incubated with neutralizing anti-integrin αvβ3, α5β1 or αM IgG or non-immune IgG for 1 hr prior to addition for 24 hrs of PKH26-stained HSC exosomes. Cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (20X) (upper; showing a representative experiment) or by spectrophotometric quantification of fluorescence in cell lysates (lower; n = 6, *p < 0.001. +p < 0.05 vs. ctrl, student’s t test). (H) Recipient HSC were transfected with a parental or CCN2 3’-UTR luciferase reporter vector for 24hrs prior to 1-hr incubation with RGD, IgG, anti-integrin αvβ3 or anti-integrin α5β1. Cells were then incubated for 24 hrs in the presence of miR-214-enriched exosomes as described [17]. Exosome-mediated suppression of luciferase activity was inhibited by RGD or anti-integrin αvβ3. n = 9, *p < 0.001 vs. ctrl, student’s t test. (I) Immunocytochemical detection of CCN2, αSMA or collagen α1 in activated HSC alone (“ctrl”) or after 36-hr incubation with exosomes from D1-3 HSC, in the presence or absence of anti-integrin αvβ3 or anti-integrin α5β1. Data are representative of 3 experiments.

The inhibitory action of exosomal miR-214 on CCN2 3’-UTR activity [17] was blocked by RGD, anti-integrin αvβ3 or anti-integrin α5β1, but not by non-immune IgG (Fig 2H). Furthermore, the ability of exosomes from quiescent HSC to suppress production of αSMA, collagen 1(α1), or CCN2 in activated HSC was also blocked by anti-integrin αvβ3 or anti-integrin α5β1 (Fig 2I). Collectively, these data show that cell surface integrins αvβ3 or α5β1 are required for exosomal delivery of regulatory miRs into HSC and down-stream phenotypic reprogramming in the recipient cells, which includes inhibition of activation- and fibrosis-associated gene expression.

Role of cell surface heparin-like molecules in exosome binding to HSC

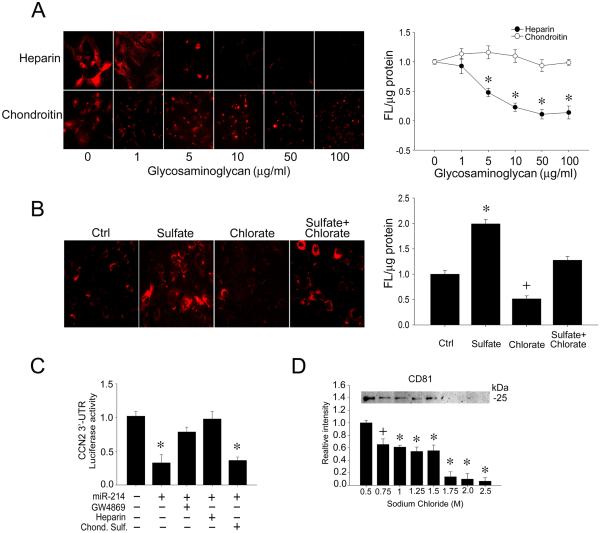

As shown in Fig 3A, incubation of exosomes with HSC was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner when heparin sulfate, but not chondroitin sulfate, was included in the incubation medium. Furthermore, pre-treatment of the HSC with sodium chlorate to selectively reduce sulfattion of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) resulted in an inhibition of exosome binding (Fig 3B). This outcome was reversed by co-incubation of the cells with sodium sulfate to rescue them from the chlorate block (Fig 3B). Finally, the biological significance of HSPG-exosome interactions was determined using a HSC-HSC co-culture system that allows exosomal communication between neighboring HSC to be examined under normal conditions of endogenous exosome production and action [12, 17]. As we have reported [17], co-culture of miR-214-transfected donor HSC with CCN2 3’-UTR luciferase reporter-transfected recipient HSC resulted in miR-214-dependent regulation of a CCN2 3’-UTR reporter, the exosome-dependency of which was shown by the ability of the exosome inhibitor, GW4869, to reverse the suppressed CCN2 3’-UTR activity (Fig 3C). Addition of heparin sulfate to the co-culture also reversed miR-214-suppressed CCN2 3’-UTR activity, whereas chondroitin sulfate was ineffective showing that exosomal cargo signaling in the recipient cells was heparin-dependent. Collectively these data show that cell surface HSPG on HSC are functional receptors for HSC-derived exosomes. To confirm the heparin-binding property of exosomes, they were incubated with heparin-affinity beads in a cell-free system with the result that they bound strongly and required ~1.0M NaCl for their elution (Fig 3D).

Figure 3. Heparin-dependency of exosome interactions with HSC.

(A) PKH26-stained exosomes (red) were incubated with primary mouse HSC for 24hrs in the presence of 0-100 μg/ml heparin or chondroitin sulfate. Cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (20X) (left; showing a representative experiment) or fluorescence intensity of cell lysates by spectrophotometry (right; n = 5, *p < 0.001 vs. 0 μg/ml heparin, student’s t test. (B) PKH26-stained exosomes (red) were incubated with primary mouse HSC for 24 hrs after 24-hr pre-treatment of the cells with sodium chlorate (10mM) ± sodium sulfate (10mM) Cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (20X) (left; showing a representative experiment) or fluorescence intensity of cell lysates by spectrophotometry (right; n = 5, *p < 0.001 ; +p < 0.05 vs. ctrl, student’s t test. (C) Donor HSC were transfected with miR-214 and co-cultured with CCN2 3’-UTR luciferase reporter-transfected recipient HSC for 24hrs. Some well also received GW4869 (10 μM; exosome inhibitor), heparin sulfate (100μg/ml) or chondroitin sulfate (100μg/ml). The inhibition of CCN2 3’-UTR activity by miR-214-enriched exosomes was reversed by GW4869 or heparin, but not by chondroitin sulfate. n = 9, * p < 0.001 vs. ctrl, student’s t test. (D) Heparin-affinity beads were mixed with exosomes (1 hr, room temp) prior to washing in PBS and mixing with different NaCl concentrations. The figure shows the extraction of residual exosomes from the heparin beads using sample buffer as assessed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot for the exosome-specific marker, CD81. The CD81 signal was not affected by 0-0.5M NaCl (data not shown). n = 6, * p < 0.001; +p < 0.05 vs. 0.5 M NaCl, student’s t test.

Discussion

In this study, we identified integrins and HSPG as cell surface molecules that are required for binding of HSC-derived exosomes to HSC. Specifically, we showed that integrin αvβ3 or α5β1 in HSC is required for exosome binding, miR uptake, and functional reprograming in the cells. This represents a novel function for integrin αvβ3 in HSC which has previously been shown to support cell survival, adhesion to CCN2, periostin-dependent activation, and osteopontin-dependent collagen up-regulation [23, 26, 30-32], all of which reflect the enhanced expression and a central role for integrin αv or αvβ3 in HSC function and hepatic fibrosis [33-35]. Similarly, integrin α5β1 in activated HSC is associated with cell adhesion to fibronectin (FN) or CCN2, or FN-dependent survival, cytoskeletal rearrangements or expression of matrix metalloproteases or collagen I [26, 36-39], but its role in binding and mediating functional effects of HSC-derived exosomes is novel. Integrin β1 on HSC also engages exosomes from liver sinusoidal endothelial cells [40] suggesting that exosomes from different cell types may compete for common integrin receptors on the same target HSC. Also, we cannot yet exclude the possibility that exosome binding involves other β1 integrins (e.g. integrin αvβ1 or α8β1, which are RGD-sensitive and expressed by HSC [41, 42]) or other RGD-sensitive integrins (e.g. integrins αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, or IIbβ3). Integrin αLβ2 on CD8+ dendritic cells or activated T cells was shown to engages ICAM-1 on dendritic cell-secreted exosomes [43, 44] but other studies have demonstrated a role for exosomal integrins in interacting with target cells [45-53] so it will be of interest in the future to determine if exosomal integrins also contribute to exosome-HSC binding interactions.

HSPG are a family of proteins substituted with glycosaminoglycan polysaccharides that interact broadly with diverse extracellular ligands, although their precise functional interactions are predominantly determined by the extent and site of side chain sulfation [54-56]. HSPG regulate cell growth, proliferation, adhesion, motility and signaling through their ability to act as high capacity low affinity co-receptors for many ligands that are consequently able to interact more efficiently with their specific cognate high affinity receptors [57, 58]. Cell surface HSPG bound to HSC-derived exosomes as evidenced by the competition studies in which exosome binding to HSC by was blocked by co-incubation with heparin sulfate or by pre-incubation of recipient HSC with sodium chlorate which selectively reduces sulfation of HSPG glycan chains during their biosynthesis in the Golgi apparatus by competitively binding to 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate synthase at the active site [59, 60]. This effect is reversible in the presence of excess sodium sulfate, a characteristic that allowed the chlorate-induced block in exosome binding to HSC to be rescued. Overall, these data demonstrate a requirement for HSPG sulfation for exosome binding and the cellular (rather than exosomal) localization of the HSPG component. While cell surface HSPG in HSC play a functional role in binding CCN2 by acting as co-receptors in association with integrin αvβ3, integrin α5β1,or low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein [23, 26, 61], our data reveal an additional role for HSPG in HSC as functional exosome receptors that are required for the action of exosomal miR-214 in target HSC. These findings are similar to the heparin-dependent binding of U-87 glioblastoma cell-derived exosomes to U-87 or CHO cells [62], although our results show that heparin-binding mechanisms are not restricted to exosomes from cancer cells. Since activated human HSC synthesize the HSPG core proteins syndecans 1-4, perlecan, and glypican [63] and syndecan-2 and glypican-1 are associated with internalized glioblastoma exosomes in U-87 cells [62], it will be of interest in future studies to determine which HSPG core proteins are involved in HSC exosome binding.

While we have identified integrin αvβ3, integrin α5β1, and HSPG as important receptors for HSC-derived exosomes and portals for exosomal cargo uptake, the involvement of these molecules in the highly specific localization of HSC-derived exosomes to HSC in HSC-hepatocyte co-cultures in vitro or to HSC in fibrotic liver in vivo remains to be established. That said, integrin αvβ3 expression in activated HSC has been mechanistically exploited for selective targeting of candidate anti-fibrotic or cytotoxic agents in experimental liver fibrosis [64-66]. The intrinsic specificity of HSC-derived exosomes for HSC suggests that such exosomes, or the molecular binding partners on their outer surface, may be exploited for targeted delivery of therapeutic drugs to activated HSC in fibrotic livers. Similar translational applications have been proposed for delivery of drugs with targeted actions to cancer cells using the HSPG-binding properties of cancer cell-derived exosomes [62]. Continued analysis of the binding partners involved in the interaction of HSC-derived exosomes with their target HSC will yield important information about the underlying mechanisms involved and their potential for use in targeted drug delivery. Furthermore, continued characterization of suppressive signaling molecules (including but not limited to miR-214 and miR-199a-5p) in exosomes from quiescent HSC offers a new direction for identifying novel anti-fibrotic agents.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01AA021276 and R21AA023626 awarded to DRB. We thank Ruju Chen and Sherri Kemper for technical assistance, Dr Min Gao (Liquid Crystal Institute, Kent State University, Kent OH) for help with cryogenic transmission electron microscopy, Dr Brian Becknell (Center for Clinical and Translational Research, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus OH) for providing mouse macrophages, and Dr Yongjie Miao (Biostatistics Shared Resource, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus OH) for assistance with statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- αSMA

alpha smooth muscle actin

- CCN2

connective tissue growth factor

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- HSPG

heparin sulfate proteoglycans

- miR

microRNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Author's contributions: LC: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical reading of the manuscript, figure preparation; DRB: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, obtained funding, study supervision.

References

- 1.Friedman SL. Hepatic fibrosis -- overview. Toxicology. 2008;254:120–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–69. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puche JE, Saiman Y, Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis. Comprehensive Physiology. 2013;3:1473–92. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Modern pathogenetic concepts of liver fibrosis suggest stellate cells and TGF-beta as major players and therapeutic targets. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:76–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R, Breitkopf K, Dooley S. Roles of TGF-beta in hepatic fibrosis. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d793–807. doi: 10.2741/A812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang G, Brigstock DR. Regulation of hepatic stellate cells by connective tissue growth factor. Front Biosci. 2012;17:2495–507. doi: 10.2741/4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman SL. Hepatic Fibrosis: Emerging Therapies. Dig Dis. 2015;33:504–7. doi: 10.1159/000374098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YA, Wallace MC, Friedman SL. Pathobiology of liver fibrosis: a translational success story. Gut. 2015;64:830–41. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P, Koyama Y, Liu X, Xu J, Ma HY, Liang S, Kim IH, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T. Promising Therapy Candidates for Liver Fibrosis. Frontiers in physiology. 2016;7:47. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon YJ, Friedman SL, Lee YA. Antifibrotic Therapies: Where Are We Now? Semin Liver Dis. 2016;36:87–98. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1571295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, Charrier A, Brigstock DR. MicroRNA-214-mediated suppression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in hepatic stellate cells is associated with stimulation of miR-214 promoter activity by cellular or exosomal Twist-1. Hepatology. 2013;58(4 (Suppl)):28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Chen R, Kemper S, Charrier A, Brigstock DR. Suppression of fibrogenic signaling in hepatic stellate cells by Twist1-dependent microRNA-214 expression: Role of exosomes in horizontal transfer of Twist1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G491–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00140.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen L, Chen R, Velazquez VM, Brigstock DR. Fibrogenic signaling is suppressed in hepatic stellate cells through targeting of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) by cellular or exosomal microRNA-199a-5p. The American journal of pathology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thery C. Exosomes: secreted vesicles and intercellular communications. F1000 biology reports. 2011;3:15. doi: 10.3410/B3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nature reviews Immunology. 2009;9:581–93. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nature reviews Immunology. 2002;2:569–79. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, Charrier A, Zhou Y, Chen R, Yu B, Agarwal K, Tsukamoto H, Lee LJ, Paulaitis ME, Brigstock DR. Epigenetic regulation of connective tissue growth factor by MicroRNA-214 delivery in exosomes from mouse or human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2014;59:1118–29. doi: 10.1002/hep.26768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charrier A, Chen R, Chen L, Kemper S, Hattori T, Takigawa M, Brigstock DR. Exosomes mediate intercellular transfer of pro-fibrogenic connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) between hepatic stellate cells, the principal fibrotic cells in the liver. Surgery. 2014;156:548–55. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh A, Sil PC. A 43-kDa protein from the leaves of the herb Cajanus indicus L. modulates chloroform induced hepatotoxicity in vitro. Drug and chemical toxicology. 2006;29:397–413. doi: 10.1080/01480540600837944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thery C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Current protocols in cell biology / editorial board, Juan S Bonifacino [et al] 2006 doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0322s30. Chapter 3, Unit 3 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chairoungdua A, Smith DL, Pochard P, Hull M, Caplan MJ. Exosome release of beta-catenin: a novel mechanism that antagonizes Wnt signaling. The Journal of cell biology. 2010;190:1079–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Matsuki Y, Ochiya T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17442–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao R, Brigstock DR. Connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) induces adhesion of rat activated hepatic stellate cells by binding of its C-terminal domain to integrin alphavbeta3 and heparan sulfate proteoglycan. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8848–8855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Goncalves R, Mosser DM. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Current protocols in immunology / edited by John E Coligan [et al] 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1401s83. Chapter 14, Unit 14 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Charrier AL, Leask A, French SW, Brigstock DR. Ethanol-stimulated differentiated functions of human or mouse hepatic stellate cells are mediated by connective tissue growth factor. J Hepatol. 2011;55:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang G, Brigstock DR. Integrin expression and function in the response of primary culture hepatic stellate cells to connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) J Cell Mol Med. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu MC, Chen CH, Liang X, Wang L, Gandhi CR, Fung JJ, Lu L, Qian S. Inhibition of T-cell responses by hepatic stellate cells via B7-H1-mediated T-cell apoptosis in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:1312–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schober JM, Chen N, Grzeszkiewicz TM, Jovanovic I, Emeson EE, Ugarova TP, Ye RD, Lau LF, Lam SC. Identification of integrin alpha(M)beta(2) as an adhesion receptor on peripheral blood monocytes for Cyr61 (CCN1) and connective tissue growth factor (CCN2): immediate-early gene products expressed in atherosclerotic lesions. Blood. 2002;99:4457–65. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schober JM, Lau LF, Ugarova TP, Lam SC. Identification of a novel integrin alphaMbeta2 binding site in CCN1 (CYR61), a matricellular protein expressed in healing wounds and atherosclerotic lesions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25808–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301534200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugiyama A, Kanno K, Nishimichi N, Ohta S, Ono J, Conway SJ, Izuhara K, Yokosaki Y, Tazuma S. Periostin promotes hepatic fibrosis in mice by modulating hepatic stellate cell activation via alpha integrin interaction. Journal of gastroenterology. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urtasun R, Lopategi A, George J, Leung TM, Lu Y, Wang X, Ge X, Fiel MI, Nieto N. Osteopontin, an oxidant stress sensitive cytokine, up-regulates collagen-I via integrin alpha(V)beta(3) engagement and PI3K/pAkt/NFkappaB signaling. Hepatology. 2012;55:594–608. doi: 10.1002/hep.24701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou X, Murphy FR, Gehdu N, Zhang J, Iredale JP, Benyon RC. Engagement of alphavbeta3 integrin regulates proliferation and apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23996–4006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311668200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson NC, Arnold TD, Katamura Y, Giacomini MM, Rodriguez JD, McCarty JH, Pellicoro A, Raschperger E, Betsholtz C, Ruminski PG, Griggs DW, Prinsen MJ, Maher JJ, Iredale JP, Lacy-Hulbert A, Adams RH, Sheppard D. Targeting of alphav integrin identifies a core molecular pathway that regulates fibrosis in several organs. Nature medicine. 2013;19:1617–24. doi: 10.1038/nm.3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patsenker E, Popov Y, Stickel F, Schneider V, Ledermann M, Sagesser H, Niedobitek G, Goodman SL, Schuppan D. Pharmacological inhibition of integrin alphavbeta3 aggravates experimental liver fibrosis and suppresses hepatic angiogenesis. Hepatology. 2009;50:1501–11. doi: 10.1002/hep.23144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patsenker E, Stickel F. Role of integrins in fibrosing liver diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G425–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00050.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pranitha P, Sudhakaran PR. Fibronectin dependent upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases in hepatic stellate cells. Indian journal of biochemistry & biophysics. 2003;40:409–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodig M, Ogunwale B, Dasarathy S, Li M, Wang B, McCullough AJ. Differences in regulation of type I collagen synthesis in primary and passaged hepatic stellate cell cultures: the role of alpha5beta1-integrin. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G154–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00432.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Juan C, de la Torre P, Garcia-Ruiz I, Diaz-Sanjuan T, Munoz-Yague T, Gomez-Izquierdo E, Solis-Munoz P, Solis-Herruzo JA. Fibronectin increases survival of rat hepatic stellate cells--a novel profibrogenic mechanism of fibronectin. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2009;24:271–82. doi: 10.1159/000233252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milliano MT, Luxon BA. Initial signaling of the fibronectin receptor (alpha5beta1 integrin) in hepatic stellate cells is independent of tyrosine phosphorylation. J Hepatol. 2003;39:32–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang R, Ding Q, Yaqoob U, de Assuncao TM, Verma VK, Hirsova P, Cao S, Mukhopadhyay D, Huebert RC, Shah VH. Exosome Adherence and Internalization by Hepatic Stellate Cells Triggers Sphingosine 1-Phosphate-dependent Migration. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:30684–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.671735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine D, Rockey DC, Milner TA, Breuss JM, Fallon JT, Schnapp LM. Expression of the integrin alpha8beta1 during pulmonary and hepatic fibrosis. The American journal of pathology. 2000;156:1927–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carloni V, Romanelli RG, Pinzani M, Laffi G, Gentilini P. Expression and function of integrin receptors for collagen and laminin in cultured human hepatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1127–36. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segura E, Guerin C, Hogg N, Amigorena S, Thery C. CD8+ dendritic cells use LFA-1 to capture MHC-peptide complexes from exosomes in vivo. Journal of immunology. 2007;179:1489–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Buschow SI, Anderton SM, Stoorvogel W, Wauben MH. Activated T cells recruit exosomes secreted by dendritic cells via LFA-1. Blood. 2009;113:1977–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wubbolts R, Leckie RS, Veenhuizen PT, Schwarzmann G, Mobius W, Hoernschemeyer J, Slot JW, Geuze HJ, Stoorvogel W. Proteomic and biochemical analyses of human B cell-derived exosomes. Potential implications for their function and multivesicular body formation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10963–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rieu S, Geminard C, Rabesandratana H, Sainte-Marie J, Vidal M. Exosomes released during reticulocyte maturation bind to fibronectin via integrin alpha4beta1. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 2000;267:583–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thery C, Boussac M, Veron P, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Raposo G, Garin J, Amigorena S. Proteomic analysis of dendritic cell-derived exosomes: a secreted subcellular compartment distinct from apoptotic vesicles. Journal of immunology. 2001;166:7309–18. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thery C, Regnault A, Garin J, Wolfers J, Zitvogel L, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Raposo G, Amigorena S. Molecular characterization of dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Selective accumulation of the heat shock protein hsc73. The Journal of cell biology. 1999;147:599–610. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clayton A, Turkes A, Dewitt S, Steadman R, Mason MD, Hallett MB. Adhesion and signaling by B cell-derived exosomes: the role of integrins. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2004;18:977–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1094fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Janowska-Wieczorek A, Wysoczynski M, Kijowski J, Marquez-Curtis L, Machalinski B, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. Microvesicles derived from activated platelets induce metastasis and angiogenesis in lung cancer. International journal of cancer. 2005;113:752–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawakami K, Fujita Y, Kato T, Mizutani K, Kameyama K, Tsumoto H, Miura Y, Deguchi T, Ito M. Integrin beta4 and vinculin contained in exosomes are potential markers for progression of prostate cancer associated with taxane-resistance. International journal of oncology. 2015;47:384–90. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fedele C, Singh A, Zerlanko BJ, Iozzo RV, Languino LR. The alphavbeta6 integrin is transferred intercellularly via exosomes. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:4545–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C114.617662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, Di Giannatale A, Ceder S, Singh S, Williams C, Soplop N, Uryu K, Pharmer L, King T, Bojmar L, Davies AE, Ararso Y, Zhang T, Zhang H, Hernandez J, Weiss JM, Dumont-Cole VD, Kramer K, Wexler LH, Narendran A, Schwartz GK, Healey JH, Sandstrom P, Labori KJ, Kure EH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, de Sousa M, Kaur S, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Brady MS, Fodstad O, Muller V, Pantel K, Minn AJ, Bissell MJ, Garcia BA, Kang Y, Rajasekhar VK, Ghajar CM, Matei I, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Lyden D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527:329–35. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belting M. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan as a plasma membrane carrier. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2003;28:145–51. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kreuger J, Spillmann D, Li JP, Lindahl U. Interactions between heparan sulfate and proteins: the concept of specificity. The Journal of cell biology. 2006;174:323–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bishop JR, Schuksz M, Esko JD. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature. 2007;446:1030–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dreyfuss JL, Regatieri CV, Jarrouge TR, Cavalheiro RP, Sampaio LO, Nader HB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans: structure, protein interactions and cell signaling. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 2009;81:409–29. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652009000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarrazin S, Lamanna WC, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Safaiyan F, Kolset SO, Prydz K, Gottfridsson E, Lindahl U, Salmivirta M. Selective effects of sodium chlorate treatment on the sulfation of heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36267–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keller KM, Brauer PR, Keller JM. Modulation of cell surface heparan sulfate structure by growth of cells in the presence of chlorate. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8100–7. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gao R, Brigstock DR. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) is a heparin-dependent adhesion receptor for connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in rat activated hepatic stellate cells. Hepatol Res. 2003;27:214–220. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(03)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christianson HC, Svensson KJ, van Kuppevelt TH, Li JP, Belting M. Cancer cell exosomes depend on cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans for their internalization and functional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17380–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304266110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roskams T, Rosenbaum J, De Vos R, David G, Desmet V. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan expression in chronic cholestatic human liver diseases. Hepatology. 1996;24:524–32. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008781318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beljaars L, Molema G, Schuppan D, Geerts A, De Bleser PJ, Weert B, Meijer DK, Poelstra K. Successful targeting to rat hepatic stellate cells using albumin modified with cyclic peptides that recognize the collagen type VI receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12743–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang XW, Wang JY, Li F, Song ZJ, Xie C, Lu WY. Biochemical characterization of the binding of cyclic RGDyK to hepatic stellate cells. Biochemical pharmacology. 2010;80:136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brigstock DR. Strategies for blocking the fibrogenic actions of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2): From pharmacological inhibition in vitro to targeted siRNA therapy in vivo. Journal of cell communication and signaling. 2009;3:5–18. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]