Abstract

Background

Animal studies describe changes in the spleen following a stroke, with an immediate reduction in volume associated with changes in the counts of specific blood WBCs. This brain–spleen cell cycling after stroke affects systemic inflammation and the brain inflammatory milieu and may be a target for emerging therapeutic studies. This study aimed to evaluate features of this brain-spleen model in human patients admitted for acute stroke.

Methods

Medical and imaging records were retrospectively reviewed for 82 consecutive patients admitted for acute stroke in whom an abdominal CT scan was performed.

Results

Mean ± SD splenic volume was 224.5 ± 135.5 cc. Splenic volume varied according to gender (p=0.014) but not stroke subtype (ischemic vs. hemorrhagic, p=0.76). The change in splenic volume over time was biphasic (p=0.04), with splenic volumes initially decreasing over time, reaching a nadir 48 hours after stroke onset, then increasing thereafter. Splenic volume was related inversely to percent blood lymphocytes (r= -0.36, p= 0.001) and positively to percent blood neutrophils (r= 0.30, p= 0.006).

Conclusions

Current results support that several features of brain–spleen cell cycling after stroke described in preclinical studies extend to human subjects, including the immediate contraction of splenic volume associated with proportionate changes in blood WBC counts. Splenic volume may be useful as a biomarker of systemic inflammatory events in clinical trials of interventions targeting the immune system after stroke.

Keywords: Stroke, spleen, inflammation

Introduction

After an ischemic stroke, the spleen is activated, affecting systemic inflammation and the brain inflammatory milieu. Animal studies describe a biphasic pattern of brain–spleen cell cycling after stroke. During an initial pro-inflammatory state, the spleen contracts over 1-4 days1-4, paralleled by increased release of lymphocytes and monocytes into the blood4, 5. This is followed by a relatively immunosuppressed state.

Such insights into the biology of systemic responses to stroke are stimulating therapeutic discovery3, 6, 7 and fostering human investigations focused on post-stroke splenic events. A study of 29 patients with confirmed/suspected ischemic stroke/TIA followed for eight days found splenic volumes tended to decrease by 24 hours then increase, and that splenic volume was inversely related to blood neutrophil, but not lymphocyte or monocyte, counts8. This study was an important exploration into splenic events following brain ischemia in humans, however some findings did not agree with preclinical data, and several questions were not addressed such as findings after intracerebral hemorrhage.

The current study retrospectively reviewed medical records, brain imaging, and abdominal CT scans from 82 patients admitted with acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. The aim of this study was to examine splenic volume and its clinical correlates in relation experimental animal data1-5.

Methods

Overview

All studies were carried out in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Irvine.

Participants

This retrospective study examined 100 consecutive patients admitted to the University of California Irvine Medical Center (1) with a discharge diagnosis of ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage, and (2) who also received an abdominal CT scan, ordered for a wide range of medical reasons. These 100 patients were admitted over a 5-year period.

Splenic volume

Splenic volume was calculated directly from the abdominal CT scans. First, a radiologist specializing in abdominal imaging determined the maximum radius of the spleen in each of the three cardinal planes (anterioposterior, craniocaudal, and transverse). Splenic volume was then calculated as 4/3π*r1*r2*r3, where r1, r2 and, r3 stand for the three radii, respectively.

Volume of the cerebral infarct

Infarct volumes were determined directly from first brain imaging using MRIcro. For ischemic strokes, stroke volume was calculated directly from the MRI scan (using the DWI pulse sequence) or if not available, head CT scan. For intracerebral hemorrhage, head CT scan was used.

Clinical Data

The clinical data extracted from the electronic medical record were age, gender, diabetes mellitus status, hypertension status, hyperlipidemia status, whether the patient received IV tPA, type of stroke (ischemic vs. hemorrhagic), time from stroke onset to abdominal CT, and time from stroke onset to the first complete blood count (CBC) with differential. Data extracted from that CBC were total WBC count, blood lymphocyte count (total and as a percent), and blood neutrophil count (total and as a percent).

Statistics

Parametric statistical methods were used for measures where the normality assumption was valid, using raw or transformed values, otherwise non-parametric methods were used. All analyses were two-tailed with alpha=0.05 and used JMP 9.0 software (SAS, Cary, NC).

Results

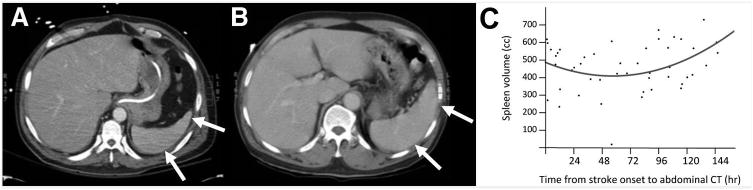

Of the 100 patient records, abdominal CT was unavailable for 10 patients, performed prior to stroke onset in 2, head CT/MRI was not available in 2, time of stroke onset could not be determined in 2, and 2 patients did not have a new stroke, leaving 82 patients who are the focus of the current report. Clinical and radiological features for the 82 subjects are summarized in Table 1. Mean (±SD) splenic volume was 224.5±135.5 cc. Examples of a smaller spleen and a larger spleen from among the 82 are provided in Figure 1. Incidental findings on the abdominal CT were common, the three most frequent examples of which were renal cyst, in 16 subjects; diverticulosis, in 12; and cholelithiasis, in 10.

Table 1. Clinical and radiological assessments.

| Age (years) | 65.9 ± 14.5 |

| Gender | 60% Male / 40% Female |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 29% |

| Hypertension | 71% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 24% |

| Received tPA | 8.8% |

| Volume of cerebral infarct (cc) | 23.8 [5.7-70.3] |

| Type of Stroke | 66% Ischemic / 34% Intracerebral Hemorrhage |

| Time from stroke onset to abdominal CT (days) | 4.2 [0.9-14.1] |

| Volume of spleen (cc) | 224.5 ± 135.5 |

| Time from stroke onset to WBC count (hours) | 9.1 [2.5-26.1] |

| Blood total WBC count (×10ˆ3/microliter) | 10.5 ± 4.0 |

| Blood lymphocyte count (×10ˆ3/microliter) | 1.6 ± 0.9 |

| Blood WBC percent lymphocytes | 17.4 ± 12.1 % |

| Blood neutrophil count (×10ˆ3/microliter) | 8.1 ± 4.0 |

| Blood WBC percent neutrophils | 73.6 ± 15.2 % |

Values are mean ± SD or median [IQR].

Figure 1.

Single slice from an abdominal CT, with arrows indicating [A] a smaller spleen (61.4 cc), imaged 13 days post-stroke, and [B] a larger spleen (418.9 cc), imaged 3 days post-stroke. [C] Splenic volume decreased over time, reaching a nadir 48 hours after stroke onset, then increased over time (p=0.04).

Splenic volume varied according to gender (251±138 cc for males vs. 185±123 cc for females, p=0.014) but not age (p=0.18), stroke subtype (ischemic vs. hemorrhagic, p=0.76), or cerebral infarct volume.

The change in splenic volume over time was examined in two ways. The first asked whether splenic volume changed over time in a simple linear manner. Results were not significant (p=0.54)—the volume of the spleen does not simply increase or decrease over time post-stroke. The second approach modeled the data as described in the prior study of splenic volume after stroke in humans8, with analysis focused on a biphasic (second order) response in patients scanned ≤8 days post-stroke. Results were significant (p=0.04), showing a decrease in splenic volume over time (reaching a nadir 48 hours after stroke onset), followed by an increase in splenic volume thereafter (Figure 1C).

The total WBC count was not related to splenic volume (p=0.10). However, splenic volume was related inversely to percent blood lymphocytes (r= -0.36, p= 0.001) and positively to percent blood neutrophils (r= 0.30, p= 0.006); in both cases, the absolute number of WBC subtypes was also significant. The amount of blood monocytes was not related to splenic volume, whether expressed as percent (p=0.17) or absolute number (p=0.91).

Discussion

Animal models describe a model whereby after a stroke, the spleen contracts as part of the systemic inflammatory response, releasing leukocytes into the bloodstream and affecting brain inflammation1-5. The current study tested features of this model in patients admitted for acute stroke. Data suggest splenic contraction followed by re-expansion associated with specific changes in WBC subtypes. Results support that many aspects of these animal models apply to humans, with some findings providing guidance to therapeutic studies building on this model.

Spleen volume does not simply change linearly over time after stroke. Instead, the change is biphasic, decreasing over 48 hours then slowly increasing thereafter. These findings match the prior study of human subjects by Sahota et al8 and are concordant with preclinical findings1-4. The results suggest the potential for splenic volume to serve as a biomarker of individual subject's systemic inflammatory response to a cerebral infarct.

Splenic volumes were significantly related to blood neutrophil counts and inversely related to blood lymphocyte counts. This suggests that the more the spleen contracts, the more lymphocytes pour into the blood, which is also consistent with findings in animal models. Less clear is the observation that the degree of splenic contraction was associated with a proportionate reduction in neutrophils, although an inverse relationship between lymphocyte and neutrophil responses after stroke in humans has been described9. The absence of a relationship between splenic volume and blood monocyte counts was unexpected. Total monocyte count may be too gross a measure in this context, as blood levels of some but not all monocyte subpopulations are modulated by systemic immune responses to stroke1, 2, 5, and so the results might indicate the importance of measuring specific monocyte subpopulations in this context.

The current study provides new insights into systemic immune changes that follow stroke. Strengths include the sample size and the inclusion of patients with either ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage. Weaknesses include the retrospective nature of this study and the availability of only one splenic volume assessment for each patient. The abdominal CT scans were ordered for clinical not research purposes, although the most common findings were incidental and unimportant. These data support the idea of the spleen as an active component of the immune response in humans after stroke and suggest insights as well as a potential biomarker for future clinical investigations that focus on modulating systemic events including the splenic response after stroke3, 6, 7.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: UL1 TR001414 and K24 HD074722.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Offner H, Subramanian S, Parker SM, et al. Splenic atrophy in experimental stroke is accompanied by increased regulatory t cells and circulating macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;176:6523–6531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seifert HA, Hall AA, Chapman CB, et al. A transient decrease in spleen size following stroke corresponds to splenocyte release into systemic circulation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:1017–1024. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9406-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vendrame M, Gemma C, Pennypacker KR, et al. Cord blood rescues stroke-induced changes in splenocyte phenotype and function. Experimental neurology. 2006;199:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurn PD. 2014 Thomas Willis award lecture: Sex, stroke, and innovation. Stroke. 2014;45:3725–3729. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim E, Yang J, Beltran CD, et al. Role of spleen-derived monocytes/macrophages in acute ischemic brain injury. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism. 2014;34:1411–1419. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu Y, Liu Q, Anrather J, et al. Immune interventions in stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:524–535. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acosta SA, Tajiri N, Hoover J, et al. Intravenous bone marrow stem cell grafts preferentially migrate to spleen and abrogate chronic inflammation in stroke. Stroke. 2015;46:2616–2627. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahota P, Vahidy F, Nguyen C, et al. Changes in spleen size in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A pilot observational study. International journal of stroke. 2013;8:60–67. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liesz A, Hagmann S, Zschoche C, et al. The spectrum of systemic immune alterations after murine focal ischemia: Immunodepression versus immunomodulation. Stroke. 2009;40:2849–2858. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.549618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]