Abstract

Risk factors of heart valve disease are well defined and prolonged exposure throughout life leads to degeneration and dysfunction in up to 33% of the population. While aortic valve replacement remains the most common need for cardiovascular surgery particularly in those aged over 65, the underlying mechanisms of progressive deterioration are unknown. In other cardiovascular systems, a decline in endothelial cell integrity and function play a major role in promoting pathological changes, and while similar mechanisms have been speculated in the valves, studies to support this are lacking. The goal of this study was to examine age-related changes in valve endothelial cell (VEC) distribution, morphology, function and transcriptomes during critical stages of valve development (embryonic), growth (post natal (PN)), maintenance (young adult) and aging (aging adult). Using a combination of in vivo mouse, and in vitro porcine assays we show that VEC function including, nitric oxide bioavailability, metabolism, endothelial-to-mesenchymal potential, membrane self repair and proliferation decline with age. In addition, density of VEC distribution along the endothelium decreases and this is associated with changes in morphology, decreased cell-cell interactions, and increased permeability. These changes are supported by RNA-seq analysis showing that focal adhesion-, cell cycle-, and oxidative phosphorylation-associated biological processes are negatively impacted by aging. Furthermore, by performing high-throughput analysis we are able to report the differential and common transcriptomes of VECs at each time point that can provide insights into the mechanisms underlying age-related dysfunction. These studies suggest that maturation of heart valves over time is a multifactorial process and this study has identified several key parameters that may contribute to impairment of the valve to maintain critical structure-function relationships; leading to degeneration and disease.

Keywords: Heart valve, endothelial cell, growth, maturation

1. Introduction

The mature heart valve leaflets are highly organized structures that open and close over 100,000 times a day to regulate unidirectional blood flow through the heart. Movement is largely facilitated by three highly organized layers of extracellular matrix (ECM) that provide all the necessary biomechanics to respond to changes in the hemodynamic environment during the cardiac cycle. In contrast, disruption to ECM organization is often associated with insufficiency that can lead to progressive heart failure.(1) Homeostasis of the valve ECM is mediated by a heterogeneous population of fibroblast-like valve interstitial cells (VICs), and previous studies have shown that VIC function is regulated by a single layer of valve endothelial cells (VECs) that line the surface of the leaflets(2–7). In addition to regulating VIC behavior, the valve endothelium serves as a physical barrier between the blood and the inner valve tissue; thereby preventing excess infiltration of circulating factors associated with risk and inflammatory cells.(2, 8) A murine wire injury model suggests that physical denudation of the aortic valve endothelium is sufficient to induce disease,(9) consistent with histological findings reporting loss of endothelial cells in diseased human valves.(10–12) In addition, VEC-specific disruption of essential signaling pathways can alter ECM organization and lead to dysfunction in mice.(3, 4, 13–16) Therefore, integrity and function of the valve endothelium appear to be essential for maintaining structure-function relationships throughout life.

Aging is a significant risk factor of heart valve insufficiency, affecting up to 13.2% of people over the age of 75.(17) Age-related disorders of the vascular system are attributed to progressive endothelial cell dysfunction and pathological landmarks and mechanisms of this process have been used as early predictors of cardiovascular disease and targeted for therapeutic treatments respectively.(18–21) These studies have largely been focused on the association of vascular endothelial cell dysfunction with impaired endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthesis. Similar to vascular endothelial cells, VECs also require NO to maintain function as reduced bioavailability of endothelium-derived NO leads to morphological defects at birth and dysfunction in adults.(4, 16, 22–25) While the requirement for NO is conserved, previous studies have noted several differences between vascular and valvular endothelial cells largely in their molecular and phenotypic response to biomechanical stress.(26) Therefore it is not clear if determinants of age-related endothelial cell dysfunction in vascular disease can account for failure of the valve to maintain structure-function relationships later in life.

To address this deficit, we investigated VEC histology, function and molecular profiles at key stages of valve development, growth, maturation, and aging. Our findings demonstrate that maintenance of the valve is a multifactorial process, and aging is associated with changes in VEC density, decreased function, reduced proliferation, and diverse molecular profiles. These findings highlight the potential mechanisms that may be abrogated in later stages of life, and potentially diseased valves that lead to impaired homeostasis.

2. Methods

2.1 Mice

Tie2GFP (Tg(TIE2GFP)287Sato/J) and wild type C57BL/6J were obtained from Jackson Labs. Mice aged to E14.5 (embryonic) post-natal day 1–3 (PN) 4 months old (young adult), and >12 months old (aging adult) were used for all studies unless otherwise stated in the text. All animal procedures were approved and performed in accordance with IACUC and institutional guidelines provided by The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

2.1.1 Isolation of VECs from Tie2GFP mice

Murine VECs were isolated from E14.5, PND2–3, 4 month-old and 12–15 month-old Tie2GFP mice as previously described by our lab.(27) Briefly, valvular tissue from both semilunar and atrioventricular valves was dissected and dissociated using collagenase IV for 7 mins at 37°C. The supernatant, containing the dissociated cells was collected and kept on ice. This process was repeated nine times in order to collect an enriched population of endothelial cells. Isolated cells were pelleted and resuspended in HBSS containing EDTA and DNaseI (RNase-free) and subjected to flow cytometry to collect the GFP+ endothelial cells as described below. All samples collected consisted of multiple (1–3 litters or mice) biological replicates pooled together to yield between 8,000 (E14.5) – 60,000 (12–15 months) GFP+ cells and approximately 10ng mRNA.

2.2 Histology

2.2.1 Bright-field and immunofluorescence

Whole embryos and whole hearts from embryonic, PN, young adult, and aging adult Tie2GFP or C57BL/6J mice were dissected and fixed overnight in 4% PFA/1xPBS at 4°C and subsequently processed for paraffin or cryo embedding. Paraffin tissue sections were cut at 7μm and subjected to Pentachrome staining according to the manufacturer (American MasterTech). Cryo-embedded tissue sections were cut at 7μm and stored −20° before immunofluorescent staining. Briefly, cryo sections were blocked for 1 hour (1%BSA, 1% cold water fish skin gelatin, 0.1% Tween-20/PBS) followed by incubation with CD31 (BD Biosciences #553370 rat anti-mouse 1:1000) or CD45 (R&D Systems AF114 rabbit 1:200) diluted in 1:1 Block/1xPBS overnight. On the next day, slides were incubated with goat-anti-rat-488 or goat-anti-rabbit-568 Alexa-Fluor secondary antibody for one hour at room temperature, mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI, and imaged on an Olympus BX51 microscope. Quantification of CD45+ cells was reported as a percentage of total DAPI+ cells in aortic valves from E14.5, PN, young and aging adult C57BL/6J mice. Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test between each time point for n=3.

2.2.2 Quantification of VEC cell density

VEC density was quantified from at least 5 aortic valve sections taken from 3 biological replicates stained with Toluidine blue. Aortic valve cusps were divided into proximal (area between annulus and hinge region), mid (area between hinge and distal tip) and distal (tip region denoted by increase in cross sectional area of the leaflet) regions based on morphology. For quantification, the number of endothelial cells on the cusp surface spanning the proximal, mid, and distal regions of young and aging adult aortic valves were counted and divided by the endothelial surface distance (μm) measured by ImageJ software. The number of VECs per 50μm of the valve surface was reported for each region. Significance was determined using the Student’s t-test between distal, mid, and proximal regions or between young and aging adult regions.

2.2.3 Transmission Electron Microscopy

Whole hearts from embryonic, PN, young adult, and aging adult C57BL/6J mice were placed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in Millonig’s PO4 with glucose for 24–48 hours at 4°C and then transferred into Millonig’s Buffer prior to aortic valve dissection. Dissected aortic valves were post fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 hours to overnight, rinsed in Millonig’s PO4 buffer, and dehydrated in graded ethanol series and cleared in propylene oxide. Tissue was then infiltrated in 50–50 Epon/Araldite–propylene oxide for 4 hours followed by infiltration in full Epon/Araldite overnight. Samples were embedded in fresh Epon/Araldite and placed in a 60°C oven for 24–48 hours. Blocks were trimmed and 500 nm thick sections were cut and collected onto slides, which were stained with Toluidine blue and assessed for areas of interest. Selected blocks were cut at 60nm on a Leica Ultracut UCT ultramicrotome. Sections were collected onto CuPd grids and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate before viewing on a Hitachi H 7650 TEM. Observations were concluded from imaging three independent aortic valve samples from each reported time point.

2.3 Culturing porcine aortic valve endothelial cells

Young and aging porcine aortic valve endothelial cells (pAVECs) were isolated from AoV cusps from 6–7 month-old juvenile pigs (young) or >2 year-old adult pigs (aging) (Animal Technologies) respectively as previously described.(28) Cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% L-glutamine, 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep), and 50U/ml heparin sodium salt (Sigma). All experiments were carried out between passages 2–5 and aging and young pAVECs were always compared at the same passage number (p2–3).

2.4 DAR-4M AM Staining

2.4.1 Cultured pAVECs

Confluent young and old pAVECs were washed with PBS and treated with 10μM DAR-4M AM (CalBioChem 251765) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then rinsed, mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector), and imaged in the Texas Red channel. Alternatively, cultures were treated with an NO donor, 250 μM DETA NONOate (Cayman Chemicals 82120), under the same culture conditions, as a positive control. For quantification, color and brightness thresholds were set using ImageJ and integrated pixel density per field of view was measured. Statistical significance between DAR-4M AM+ young and aging pAVECs was determined using the Student’s t-test for n=4.

2.4.2 Murine aortic valves

Tie2GFP PN and aging adult mice were euthanized and gravity perfused through the left ventricle with 1xPBS until blood had been flushed out of the heart, followed by a 10 min perfusion with 0.01 mmol/L DAR4M- AM/PBS.(29) Hearts were then flushed with 1xPBS perfusion for 10 minutes followed by 4% PFA for 5 minutes. Hearts were removed and fixed in 4% PFA for 1 hour at room temperature before cryo-embedding. 7um cryo sections were rinsed in PBS, mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector), and viewed in the Texas Red-568 channel. The number of DAR-4M AM+ cells per field of view was calculated in images of aortic valves from PN and aging mice and reported as a percentage of total DAPI+ cells.

2.5 CellROX Staining for Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Hearts from PN and aging adult wild type mice were harvested and immediately cryo-embedded without fixation. On the same day, 7μm sections were cut and mounted. Slides were washed briefly with PBS and incubated with 5μM CellRox reagent (Fisher C10422) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Immediately following, slides were washed and mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI and imaged in the FITC 488 channel on an Olympus BX51 microscope. The number of CellROX+ cells, per field of view, was calculated in images of aortic valves from PN and aging mice and reported as a percentage of total DAPI+ cells for n=3.

2.6 EMT assay using pAVECs

Young and aging pAVECs were grown to confluency on plastic 24 well plates (for RNA extraction) or on Matrigen Softwell Custom collagen I coated, 8Kpa, hydrogel plates (for immunocytochemistry). Cells were treated with fresh medium, supplemented with TGF-β1 (2ng/ml) or with equal volumes of 0.1% BSA every 2–3 days for 7 days. Following culture, cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 30 minutes at room temperature and stored in PBS until immunocytochemistry or lysed in Trizol (Invitrogen) RNA extraction respectively (n=8). For immunostaining, cells were 4% PFA- (SMA) or methanol-fixed (VE-cadherin) for 20 minutes, blocked and incubated with primary antibodies against VE-cadherin (Santa Cruz SC-6458, 1:100) or SMA (Sigma A2546, 1:100) for two hours at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were applied as described above (2.1.1).

2.7 In Vivo Permeability With Evans Blue Dye (EBD)

5μg/μl/10g body weight Evans Blue Dye (Sigma) was injected via tail vein into PN and aging adult C57BL/6J mice. Twenty-four hours later, mice were sacrificed and subjected to whole body perfusion with 1xPBS, after which, hearts were dissected and immediately frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound. Tissue was cut into 7μm sections and post-fixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes at room temperature. Slides were then washed briefly in PBS and mounted in aqueous mounting medium. The presence of Evans blue dye fluorescence within aortic valves was imaged in the Texas Red channel on an Olympus BX51 microscope and overlaid with bright-field differential interference contrast (DIC) images (n=3).

2.8 In vitro permeability assay

In vitro permeability assays were carried out as described previously.(30) Briefly, young and aging pAVECs were plated on collagen-coated 6.5 mm diameter, 3.0μm pore size transwell inserts (Corning). Two monolayers were plated in each insert at a density of 1×105 over a period of 48 hours. 24 hours later Dextran-TMR (Life Tech D-1868) was added to the lower chamber of each well. 10μl of media was removed from the upper compartment at 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after treatment, and diluted 1:10 in water. Diluted samples were analyzed with spectroscopy at 555-excitation/580-emission (n=4).

2.9 Cell stretching membrane injury assay

Aging and young PAVECs were grown to 95–100% confluency on collagen coated 6-well BioFlex culture plates (FlexCell International). Directly before the experiment, fresh cell media (see above) was added containing 0.4mg/mL 4,000MW FITC-dextran. Cells were then subjected to 20 minutes of either 0% (no stretch) or 18% equibiaxial strain on Flexcell FX-5000 tension system. The plate was then washed twice with 1xPBS and incubated for 10 minutes in 4mM Ethidium bromide. Following two further 1xPBS washes, the membranes were cut out with a scalpel and placed on a dish with 1xPBS for imaging. Fluorescent images were captured with an Olympus IX81 microscope, using CY3 and FITC filters. 4 images were taken randomly within a 12.5mm radius of the center of each well using identical lamp intensity and exposure times. The number of FITC and Ethidium Bromide positive cells were then manually counted using ImageJ software over a total of three biological replicates. Under these conditions, FITC positive cells experienced plasma membrane rupture followed by active membrane repair to retain the FITC dextran. Ethidium bromide positive cells have permanent plasma membrane rupture (dead cells). Injured and repaired cell fractions were calculated as the total number of FITC-dextran labeled cells divided by the total number of cells while dead cell fraction was determined by counting the number of EB labeled cells and dividing by the total number. Cells labeled with both EB and FITC-dextran were counted as dead. Areas of cell detachment were determined by outlining cell borders and calculating the cell area as a percentage of the total image area (n=3).

2.10 Cell Cycle Analysis

2.10.1 EdU injections and quantification

PND7, young adult, and aging adult mice were injected subcutaneously with 5μg/g body weight EdU (Invitrogen). 7 hours later, mice were sacrificed and hearts were harvested. Alternatively, mice were injected once a day for 7 days and tissue was harvested 2 weeks later. Tissue was fixed in 4% PFA overnight and processed for cryo-embedding. 7μm sections were subjected to Click-it EdU (Invitrogen) detection and immunofluorecent staining for CD31 (BD Biosciences rat #553370 anti-mouse 1:1000) according the manufacturer’s instructions.

Proliferating VECs were detected by co-expression of CD31 and EdU. Every 6th tissue section spanning the aortic valve region was collected and used for quantification (n=3). Significance was determined using the student’s t-test between PND7 and young adult mice injected with a 7h single dose or between PND21 and young adult, PND21 and aging adult, or young adult and aging adult 7d pulse samples.

2.10.2 DNA content analysis of isolated murine VECs

Isolated VECs from PN and young adult mice, as described previously in 2.1 and by our lab(27). Cells were then pelleted, resuspended in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at 37°C, and chilled on ice for one minute. Fixed cells were stored in 1% sodium azide/PBS at 4°C until analysis. On the day of analysis, cells were permeabilized in 90% Methanol on ice for 30 minutes, rinsed, labeled with 1ug/ml DAPI (Pierce) with 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated at 37° for 30 minutes. Cells were analyzed for DNA content using an Aria III cell sorter in which ~2,500 events were captured and Modfit software was used to determine DNA content after removal of aggregates (n=4). Student’s t-test was used to determine significance between GFP+ PN and young-adult cells in G1 phase or S/G2 phase, or between GFP+ and GFP− cells.

2.11 Valve Endothelial Cell Isolation and RNA-seq

VECs from embryonic, PN, young adult, and aging adult (12–15 months) mice were isolated as previously described by our lab(27) and described in 2.1.1. Isolated cells were stored in Trizol and submitted for RNA extraction and RNA sequencing at Ocean Ridge Biosciences (Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, USA). Sequencing was performed on a HISeq 2500 and all samples had a minimum of 83 million passed filter reads. Reads were aligned with 79% efficiency to the UCSC mm10 reference genome. Normalized counts of sequence reads (RPKM) were annotated to Ensembl genes and values were filtered to retain a list of genes with a minimum of approximately 50 mapped reads in one or more samples. Differential gene expression was assessed by Tukey test. Fold changes below the reliable detection threshold (50 reads/gene) were reported at “NA”. Statistical significance and false discovery rates were calculated using linear regression and the Benjamini and Hochberg methods respectively. Pathway analysis was preformed using WebGestalt software in which KEGG, Wiki Pathways, and GO Pathways are queried to report the statistically significant distribution of differentially regulated genes among functional biological pathways.

2.12 Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was extracted from murine VECs and pAVECs with Trizol according the manufactures protocol (Invitrogen) and cDNA and PCR reactions were performed as previously reported by our lab(31). Quantitative real-time PCR using a Step One Plus Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) was used to detect changes in gene expression for Col4a2, Itga1, Rbm47, Chrdl1, Trim55, and Hrh2 using Primetime assays from Integrated DNA Technologies; normalized to GAPDH and for α-SMA, Snai1, von Willebrand Factor (vWF), and Tie2 using Taqman probes; normalized to 18S. Fold change was determined relative to control and significance was calculated using student’s t-test (n=3–6).

3. Results

3.1 VEC density and cell-cell connections decrease with growth and maturation

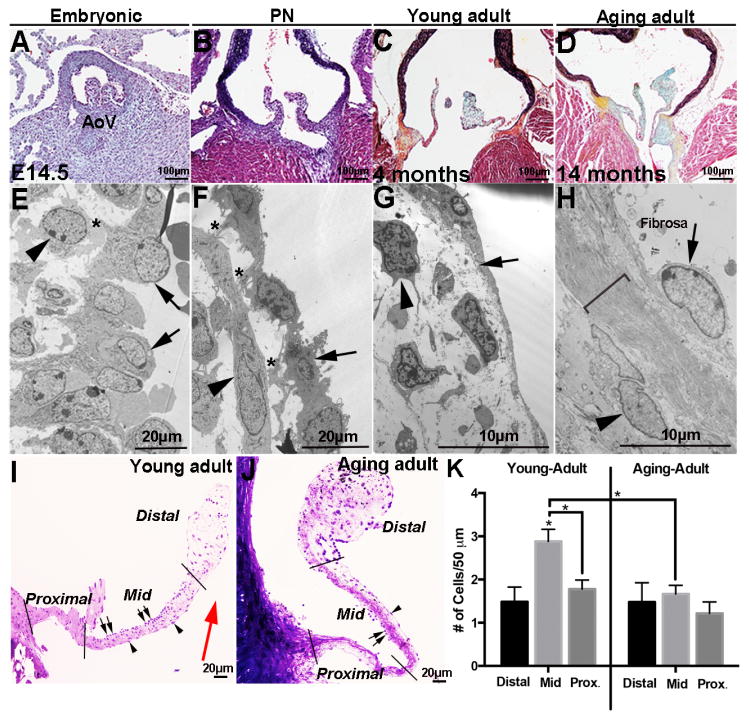

To examine age-associated changes in aortic valve structure, histological analysis was performed at embryonic (E14.5, post-EMT early remodeling), PN (PND1–3, growth and elongation), young adult (4 months, maintained), and aging adult (>12 months, aging) stages (Figures 1 A–D). As indicated by Movat’s Pentachrome stain, developing valves at embryonic stages are enriched in proteoglycans (blue, Figures 1A, B) and by the young adult stage, collagen (teal/yellow) and elastin (black) (Figures 1C and D) are more detectable consistent with previous reports detailing specific collagen types and elastin.(1), (32) In addition to the ECM, transmission electron microscopy analysis reveals temporal changes in valve cell morphology (Figures 1 E–H). At the embryonic stage, VECs are cobble-stone like in shape, dense (arrows, Figure 1E), and in physical contact with underlying VICs (*, and arrowhead, Figure 1E). By PN stages, VEC morphology is more flattened (arrows, Figure 1F), and contact with VICs is observed (*, Figure 1F). In young adults, VECs exhibit long cytoplasmic extensions along the cusp surface (arrow, Figure 1G), and physical contacts with VICs are grossly rare. In the aging mouse, VEC nuclei are larger (arrow, Figure 1H) with extensive bundles of ECM fibers (bracket, Figure 1H) separating them from underlying VICs (arrowhead, Figure 1H). Toluidine blue staining of young and aging adult aortic valves highlights age-dependent changes in the spatial distribution of VECs in the ‘mid’ region of the cusp (Figure 1I–K) with a significant decrease associated with aging. Despite changes in VEC density, the relative percentage of VICs (~66.7%) and VECs (~33.2%) per field of view at embryonic through aging stages remains constant (data not shown).

Figure 1. Valve endothelial cell morphology, distribution, and cell contacts change with growth and maturation.

(A–D) Movat’s Pentachrome staining to detect the deposition and organization of collagen (yellow), proteoglycan (blue), elastin (black), and muscle (red) in aortic valves from wild type mice at embryonic (E14.5) (A), post natal (PN) (B), young adult (4 months) (C) and aging adult (14 months) (D) stages. (E–H) Transmission electron microscopy of aortic valves at indicated time points. Arrows indicate valve endothelial cells (VECs), arrowheads show valve interstitial cells (VICs), and *denote contact between VECs and VICs. Bracket in H indicates expanded extracellular matrix. (I, J) Toluidine blue staining of aortic valves from young (4 months) and aging (15 months) wild type mice to show VEC density on fibrosa (arrows) and ventricularis (arrowhead) cusp surfaces. (K) Number of VECs on the surface of aortic valve cusps in distal, mid and proximal regions as indicted, n=3. Statistical significance based on *P<0.05. AoV, aortic valve.

3.2 VEC function declines with growth and maturation

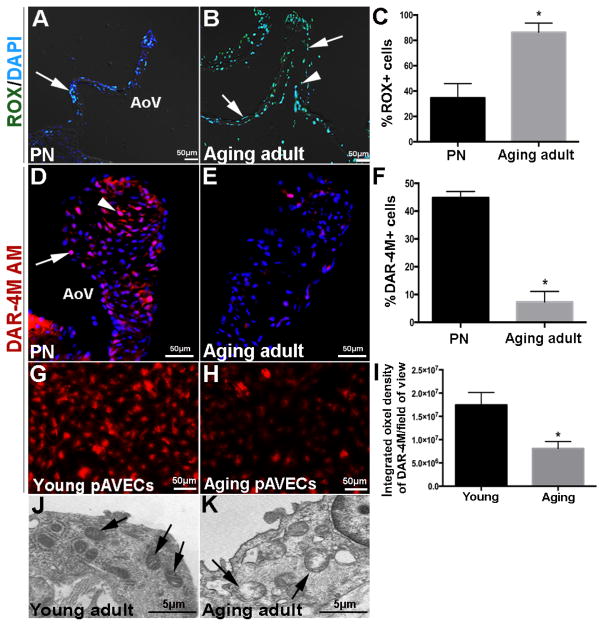

Reduced endothelial nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production have been associated with valve disease onset, consistent with other cardiovascular systems.(4, 7, 33–35) At the post-natal stage, ROS was detected by CellROX (ROX) reagent in VECs and VICs at low levels (Figure 2A, C) and this was consistent with high NO production as indicted by DAR-4M AM staining (Figure 2D, F). In contrast, ROX was high (Figure 2B, C) and DAR-4M AM (Figure 2E, F) low at aging stages. To further support these findings, pAVECs isolated from >2 year-old aging pigs also demonstrated decreased NO production (Figure 2H, I) compared to pAVECS from younger (6 months) adult animals at the valve maintenance stage (Figure 2G, I). In association with oxidative stress, mitochondria within VECs from aging adult mice show mitochondrial disorganization (Figure 2K) compared to younger time points (Figure 2J). Together, this suggests that NO bioavailability and cell metabolism is impaired in aging VECs.

Figure 2. Nitric oxide availability and mitochondrial organization are impaired with growth and maturation.

(A, B) Aortic valves from post natal (PND7) (A) and aging adult (25 months) (B) wild type mice stained with CellROX reagent to detect reactive oxygen species in VECs (arrows) and VICs (arrowheads). (C) Percentage of ROX-positive cells over total number of cells (n=3). (D, E) DAR-4M-AM staining denoting nitric oxide availability in PN (C) and adult aging (19 months) (D) wild type aortic valves. (F) Percentage of DAR-4M AM-positive cells over total number of cells (n=3). DAR-4M-AM staining in cultured porcine aortic valve endothelial cells from young (G) and aging (H) animals. (I) Percentage of DAR-4M AM-positive cells over total number of cultured cells per field of view (n=3). (J, K) Transmission electron microscopy to show mitochondrial organization (arrows) in VECS from young adult (4 months) (J) and aging adult (14 months) (K) aortic valves of wild type mice. AoV, aortic valve. Statistical significance based on *P<0.05 in aging adult valves compared to post natal (PN) stages (n=3).

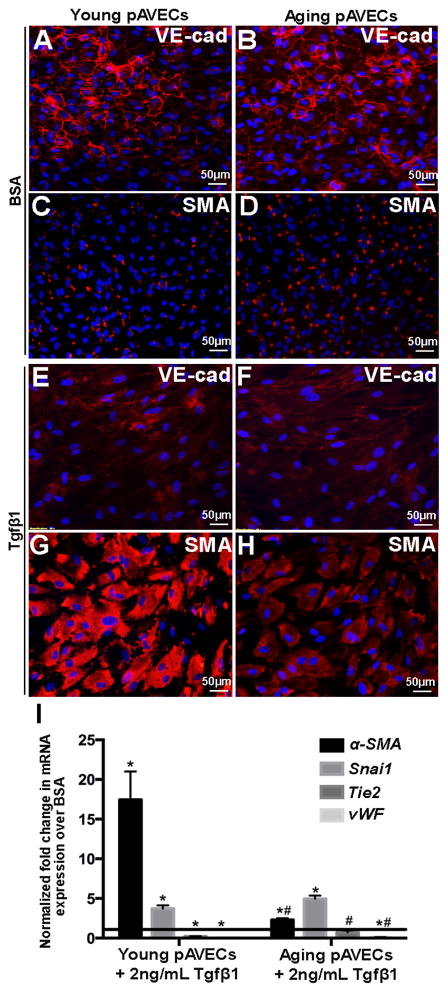

Previous studies have suggested that VECs undergo endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) to replenish the VIC population over a lifetime.(5, 6, 36, 37) To examine differences in EMT potential, young and aging pAVECs with cobblestone-like morphology (Figure 3A, B) were treated with 2ng/mL of the potent inducer, TGFβ1. After 7 days, expression of the endothelial cell markers VE-cadherin, Tie2 and von Willebrand Factor (vWF) were decreased (Figures 3E, F, I), while the mesenchyme marker smooth muscle α-actin (SMA) was increased more significantly in treated young pAVECs (Figures 3G, I) compared to BSA controls (Figures 3C, I) and aging pAVECs (Figures 3H, I).

Figure 3. TGFβ1-mediated EMT is decreased with growth and maturation.

(A–D) Immunofluorescent staining against the endothelial marker VE-cadherin (A, B, E, F) and mesenchymal marker, α-SMA (C, D, H, H), in young (A, C, E, G) and aging (B, D, F, H) pAVECs treated with 2ng/ml TGFβ1 every 2–3 for 7 days (E–H) compared to BSA treated controls (A–D). (I) Quantitative PCR to show fold changes in Tie2, vWF (endothelial), Snai1 and α-SMA (mesenchyme) in young and aging TGFβ1-treated pAVECs compared to BSA-treated controls. Fold change relative to BSA controls, n=8. *p=<0.05 compared to BSA control, #p=<0.05 compared to TGFβ1-treated young pAVECs.

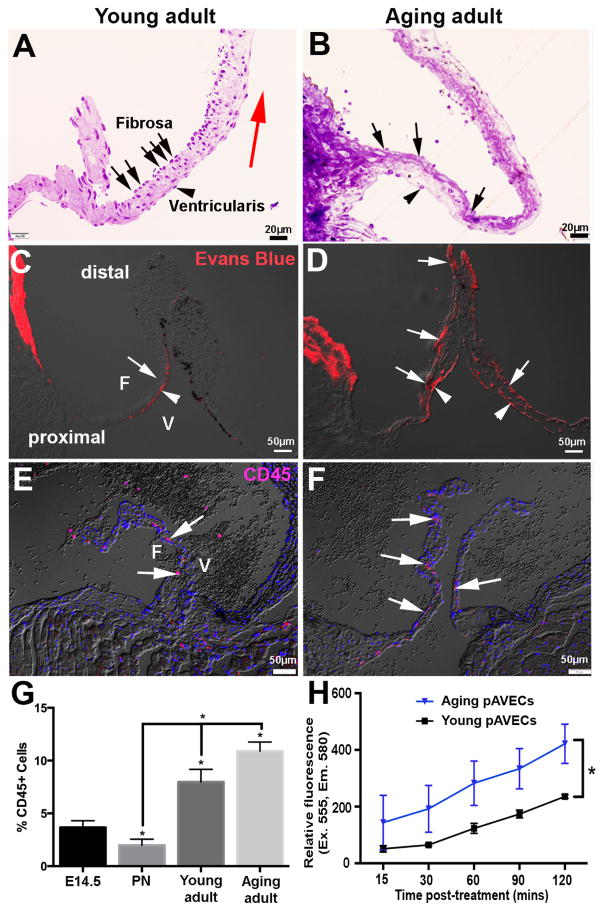

In valves, the endothelium serves as a physical barrier to protect the underlying tissue from hemodynamic stress and circulating factors.(2, 8) To determine potential age-related changes in endothelial permeability, young adult and aging adult wild type mice were subject to tail vein injections of Evans Blue dye (EBD). In aortic valves from young mice, permeation across the endothelium was low and localized within the proximal region on the ventricularis side (arrowheads Figures 4A, C); consistent with low VEC density (Figures 4A, 1K). However, in the aging adult EBD was observed along the ventricularis (arrows, Figure 4D) and fibrosa (arrowheads, Figure 4D) surfaces at proximal and distal regions, consistent with reduced VEC density during aging (Figure 4B). This age-dependent increase in endothelial permeability correlates with increased infiltration of circulating CD45+ cells at the aging stage (Figures 4 E–G). In support of in vivo findings, permeability assays in vitro demonstrate that compared to young, aging pAVECs are significantly more permeable (Figure 4H).

Figure 4. The valve endothelium is more permeable with maturation.

(A, B) Toluidine blue staining of young adult (4 months) (A) and aging adult (14 month) (B) wild type aortic valves to show VEC density over the surface of the fibrosa (arrows), compared to the ventricularis (arrowheads). (C, D) Evans blue dye to determine permeability of the valve endothelium in young adult (C) and aging adult (D) wild type mice. (E, F) CD45 detection to show expression of infiltrating hematopoietic cells in young adult (E) and aging adult (F) aortic valves; quantitation shown in (G). (H) Quantitation of relative fluorescence of permeated Dextran-TMR in young and aging pAVECs, n=4. *p=<0.05 compared to young pAVECs.

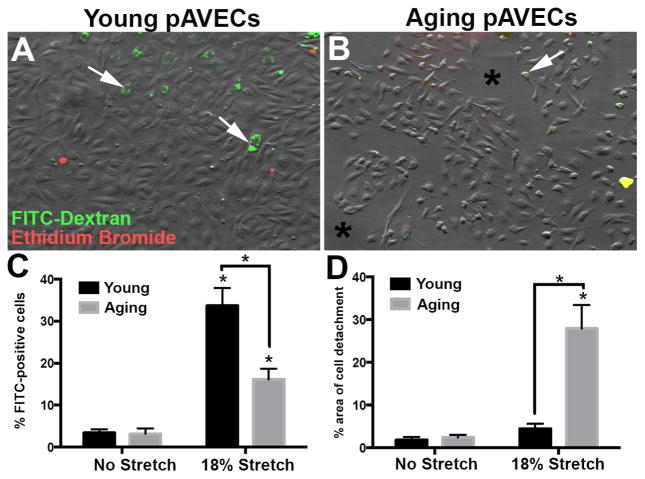

3.3 Young pAVECs are more resistant to stretch-induced injury in vitro

To determine potential differences in cell membrane repair of young and old valve endothelial cells following physical injury, pAVECs were subjected to no stretch or 18% equibiaxial stretch at 1Hz for 20 minutes in the presence of FITC-labeled Dextran. As shown in Figure 5, the number of FITC-positive cells is higher in 18% stretched young pAVECs, compared to stretched aging pAVECs and no stretch controls (Figures 5A–C). pAVECs were treated with Ethidium Bromide to label cells with permanent plasma membrane breaks (necrosis), however negligible levels were detected in young and aging cells (Figures 5A, B). In association, the number of detached cells after 18% stretch is greater in aging, compared to young, or unstretched pAVECs (Figure 5D). Taken together this data suggests that aging pAVECs have a greater cell detachment after stretch-induced injury, while young pAVECs are able to self repair their cell membrane to promote survivability.

Figure 5. Cell membrane repair following stretch-induced injury decreases with maturation.

(A, B) DIC images to show morphology and distribution of young (A) and aging (B) pAVECs following 18% equibiaxial stretch at 1Hz for 20 minutes. Green staining indicates cell-retained FITC-Dextran, while Propidium Iodide is in red with negligible detection. Quantitation of FITC-positive cells are shown in C, and D indicates the % of detached cells under each condition, n=3, p<0.05 in aging compared to young pAVECs.

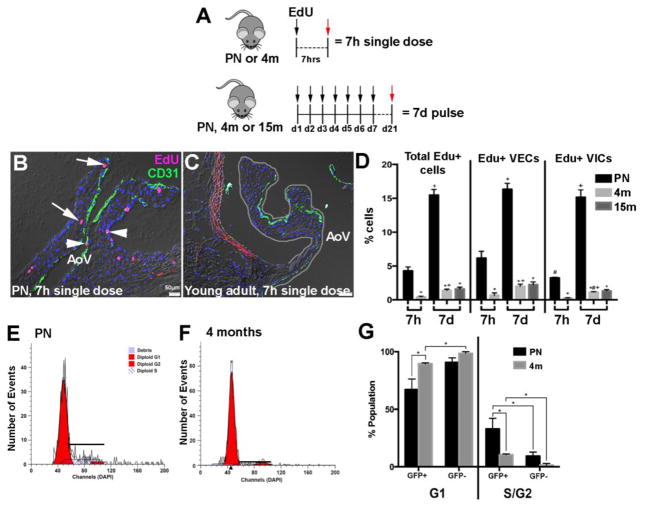

3.4 Proliferation of VECs significantly declines after post-natal stages

To examine potential changes in valve cell proliferation with aging, PN or young adult wild type mice were either injected with a single dose of EdU and harvested 7 hours later (7h single dose), or PN, young adult, or aging adult wild type mice were injected daily for 7 consecutive days (7d pulse) and harvested 2 weeks later (Figure 6A). Immunohistochemistry using anti-EdU on 7h single dose PN mice shows that ~6.2% of VECs (of the total VEC population) and ~3.3% of VICs (of the total VIC population) are proliferative (Figures 6B–D). These numbers are significantly higher than that observed in 7h single dose-treated young adult mice (~0.7% VECs, ~0.3% VICs), respectively. As expected, the 7d pulse approach captured a higher percentage of cells proliferating in all stages; however, proliferation rates of VECs and VICs were similar at the PN stage (Figure 6D). By the young adult stage, rates of both VECs (~2%) and VICs (~1.1%) were significantly lower than PN stages (~16.3% VECs, ~15.2% VICs), however, VECs (~2%) maintain a higher proliferative capacity than VICs (~1.1%). No significant differences in cell proliferation were noted between young and aging adult time points. To support EdU in vivo data, murine VECs from endothelial cell reporter (Tie2-GFP) mice were isolated by flow cytometry and co-stained with DAPI to examine DNA content (Figures 6E–G). Consistently, a higher percentage of Tie2-GFP+ cells were observed in S and G2 phases during PN stages when compared to young adults. In addition, the number of proliferating VECs at PN and adult stages was higher than Tie2-GFP negative cells that are likely rich in the VIC population.

Figure 6. VEC proliferation declines with maturation.

(A) Experimental design of EdU labeling in PN, young adult (4 months), and aging adult (15 months) aortic valves. (B, C) Representative aortic valves labeled with EdU (red) and CD31 (green) from 7h single dose treatment in PN (B) and young adult (4 months) (C) wild type mice. Arrowheads indicate EdU+ VECs, EdU+ VICs are marked by arrows. (D) Quantification of EdU+ VECs and VICs in aortic valves at indicated time points. n=3, *p=<0.05 compared to PN, #p<0.05 compared to EdU+ VECs, +p<0.05 compared to 7h. (E, F) Flow cytometry to show DNA content of isolated VECs from PN (E) and young adult (4 months) (F) Tie2GFP mice, n=3. (G) Quantification of Modfit DNA content curves of isolated VECs (GFP+) and non-VECs (GFP−).

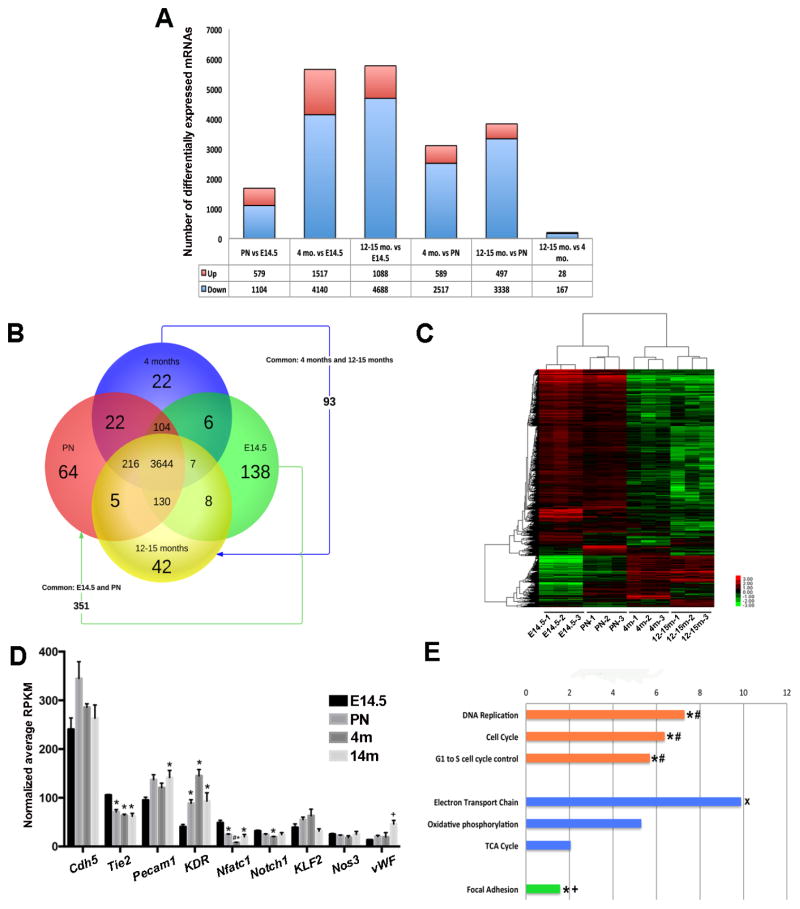

3.5 VECs have age-dependent mRNA profiles

In order to define the molecular profiles of age-related changes in VECs, RNA-seq was performed on VECs isolated from embryonic, PN, young adult, and aging adult Tie2-GFP mice using published methods.(27) Analysis revealed several mRNAs differentially expressed between each time point, with the largest change observed between embryonic and aging adults, and the smallest between young and aging adults (Figures 7A, B). This approach also revealed mRNAs that were unique (Supplementary Table 1) and common (Supplementary Table 2) to VEC populations at one, or more time points (Figure 7B), as well as distinct gene clustering patterns (Figure 7C) at each stage (see Supplementary Figure 1 for validation). As expected several ‘classic’ endothelial markers were expressed in VECs, many of which demonstrate age-dependent expression patterns (Figure 7D). Additional Wiki bioinformatics analysis highlight biological functions predicted to be affected by differentially expressed genes at each time point. Of the mRNAs downregulated between PN and aging adults (and other time points as indicated in Figure 6E), Cell Cycle (orange, Figure 7E), Focal Adhesions (green, Figure 7E) and Oxidative Phosphorylation (blue, Figure 7E) pathways were enriched supporting findings for reduced proliferation (Figure 6), increased permeability (Figure 4) and disorganized mitochondria (Figures 2G, H).

Figure 7. Age-dependent mRNA profiles of VECs.

(A) Summary of the number of differentially expressed mRNAs between two comparative time points. (B) Venn diagram to show the number of protein-coding mRNAs (4852 total) expressed between time points based on ANOVA P-score <0.01 and max fold change >2. (C) Heat map to show hierarchal clustering between 3 biological replicates at each time point based on RPKM values for 10,024 significant genes, with a false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.1. (D) Graph to show average RPKM values of detected endothelial cell markers. p<0.05 compared to E14.5 (*), PN (#) and 4 months (+). (E) WikiPathway analysis of –Log(P-value) of mRNAs significantly downregulated between PN and aging adult (12–15 months) time points. Orange indicates biological functions related to cell proliferation, processes shown in blue are related to cell metabolism, and green highlights focal adhesion. *p<0.05 between PN and young adult (4 months); #p<0.05 between embryonic (E14.5) and young adult (4 months); +p<0.05 between embryonic (E14.5) and PN; *p<0.05 between young adult (4 months) and aging adult (12–15 months).

4. Discussion

This current study demonstrates that VECs undergo significant age-related changes related to morphology and distribution, function and gene expression. We observe that aging VECs have lower cell proliferation rates, attenuated nitric oxide production, increased ROS, disorganized mitochondria, decreased SMA expression in response to TGFβ1 treatment and reduced cell membrane self repair in response to stretch-induced injury. These functional deficits are accompanied by a decline in endothelial cell density that correlates with increased permeability in older valves. Moreover, VECs express age-dependent transcriptional profiles, many of which support the observed decline in function. Thus, this study has made a significant contribution towards defining the characteristics of endothelial cell dysfunction, and produced a large-scale data set to define the molecular traits of VECs that likely contribute to age-related valve dysfunction.

Aging is a significant risk factor of valvular insufficiency, however the underlying mechanisms of valve maintenance that decline with age are not known. Using single dose, or pulse chase EdU we show that VIC and VEC proliferation rates are highest at PN stages compared to young and aging time points (Figure 6), and this is supported by pathway analysis of RNA-seq data showing that proliferation is as equally high at embryonic stages (Figure 7). Consistent with a decline in valve growth and remodeling, proliferation significantly decreases in both cell populations by young adulthood (VECs −14.3%; VICs −14.0%), with a further decline during aging (VECs −0.24%; VICs −0.18%). Our study demonstrates that VECs have higher relative proliferation rates than VICs (Figures 6D and G). It is not clear why, but we speculate that more VECs proliferate after birth to maintain ‘endothelial coverage’ over the valve surface as the cusp elongates and thins during post natal growth and remodeling. While our study did not examine changes in the absolute numbers of VECs and VICs with aging, we can conclude that generation and expansion of the VEC and VIC pools occur during embryonic and post natal development, and beyond this, turnover of resident cells is low although the ratio between VEC and VIC number remains constant.

Histological analysis shows that VEC density within the endothelium is age dependent. At the embryonic stage, the cobblestone-like VECs are in close contact with each other, however the ‘clustering’ or density of VECs decreases with age (Figures 1I–K). In addition, physical contact between VECs and underlying VICs also declines. As a result, molecular communication between these cell types may become dysregulated with age, which in turn, could have significant implications on maintaining homeostatic phenotypes.(2–7) Changes in cell-cell contact are consistent with overrepresentation of downregulated mRNAs associated with focal adhesions (Figure 7E) and increased permeability (Figures 4C, D) at older time points. At the young adult stage, VEC distribution within the endothelium is not uniform, but cells are notably more clustered in mid regions on the fibrosa surface away from laminar blood flow. As expected, regions associated with low VEC density (ventricularis surface, distal) are associated with hyper-permeability particularly in aged valves (Figures 4A–D), which may relate to increased infiltration of pathological stimuli including risk factors and excess inflammatory cells from the circulation in the older population.(38, 39) Furthermore, the ability of individual VECs to self repair their plasma membrane following injury induced by equibiaxial stretch is reduced with aging and this is associated with increased cell detachment which may further impact permeability.

In this study we utilized non-biased, high-throughput analysis to provide a much-needed database of VEC transcriptomes for the continued pursuit of identifying endothelial-mediated mechanisms of valve pathology. Our data shows that 83% of differentially expressed mRNAs are common to VECs at all time points (Figure 7B) and as expected, these include ‘classic’ endothelial markers (Figure 7D). The greatest number of differentially expressed genes was observed between embryonic and aging adults (1088 up, 4140 down), reflecting significant molecular diversity between development and degeneration. The least number of differentially expressed genes was observed between young and aging stages (28 up, 167 down). This suggests that molecular traits of VECs during stages of valve maintenance (young adulthood) are not significantly different from that of aged valves. Despite fewer mRNA changes cell function is notably impaired between maintenance and aging stages. This could be attributed to defects in transmission of signaling pathways between neighboring cells as a result of decreased cell-cell interactions (see Figure 1). In addition, it is also considered that RNA-seq does not capture post-translational or epigenetic modifications that could occur with aging.

5. Conclusions

Extensive studies in other cardiovascular diseases demonstrate that maintenance of an intact and functional endothelium is important for protecting against degeneration and disease. In the valves, a similar mechanism has been speculated but few studies exist to address this directly. This study provides new evidence that aging of VECs is associated with a decline in function that likely results in impairment of the valve to maintain structure-function homeostasis at the level of serving as a physical barrier, regulating VIC behavior and age-related differences in ECM composition and arrangement.(40–42) While our study focuses on aging in wild type mice, moving forward the field is now poised to consider the complexities of genetic alterations and the hemodynamic environment on VEC dynamics in mouse models of human valve disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

VEC function including, nitric oxide bioavailability, metabolism, endothelial-to-mesenchymal potential, membrane self repair and proliferation decline with age.

VEC distribution and density over the surface of the aortic valve is age-dependent

VECs express age-dependent transcriptomes related to changes in important biological functions

Acknowledgments

We thank David Willoughby and Casey Nagel from Oceanridge Biosciences for RNA-seq analysis, as well as Cynthia McCallister, Blair Austin, Punashi Dutta, Bailey Dye and Tori Horne for technical support. This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI R01HL127033 (JL), AHA GRNT19630003 (JL), and AHA PRE19880008 (LJA).

Footnotes

Disclosures. None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hinton RB, Jr, Lincoln J, Deutsch GH, Osinska H, Manning PB, Benson DW, et al. Extracellular matrix remodeling and organization in developing and diseased aortic valves. Circ Res. 2006;98(11):1431–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224114.65109.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao G, Kotick JD, Lincoln J. Heart valve development, maintenance, and disease: the role of endothelial cells. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2012;100:203–32. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387786-4.00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huk DJ, Austin BF, Horne TE, Hinton RB, Ray WC, Heistad DD, et al. Valve Endothelial Cell-Derived Tgfbeta1 Signaling Promotes Nuclear Localization of Sox9 in Interstitial Cells Associated With Attenuated Calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(2):328–38. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosse K, Hans CP, Zhao N, Koenig SN, Huang N, Guggilam A, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide signaling regulates Notch1 in aortic valve disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;60:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapero K, Wylie-Sears J, Levine RA, Mayer JE, Jr, Bischoff J. Reciprocal interactions between mitral valve endothelial and interstitial cells reduce endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and myofibroblastic activation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;80:175–85. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjortnaes J, Shapero K, Goettsch C, Hutcheson JD, Keegan J, Kluin J, et al. Valvular interstitial cells suppress calcification of valvular endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(1):251–60. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrar EJ, Huntley GD, Butcher J. Endothelial-derived oxidative stress drives myofibroblastic activation and calcification of the aortic valve. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helske S, Kupari M, Lindstedt KA, Kovanen PT. Aortic valve stenosis: an active atheroinflammatory process. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18(5):483–91. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282a66099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honda S, Miyamoto T, Watanabe T, Narumi T, Kadowaki S, Honda Y, et al. A novel mouse model of aortic valve stenosis induced by direct wire injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(2):270–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han RI, Clark CH, Black A, French A, Culshaw GJ, Kempson SA, et al. Morphological changes to endothelial and interstitial cells and to the extra-cellular matrix in canine myxomatous mitral valve disease (endocardiosis) Vet J. 2013;197(2):388–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riddle JM, Wang CH, Magilligan DJ, Jr, Stein PD. Scanning electron microscopy of surgically excised human mitral valves in patients over 45 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63(7):471–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein PD, Wang CH, Riddle JM, Sabbah HN, Magilligan DJ, Jr, Hawkins ET. Scanning electron microscopy of operatively excised severely regurgitant floppy mitral valves. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64(5):392–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90543-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laforest B, Andelfinger G, Nemer M. Loss of Gata5 in mice leads to bicuspid aortic valve. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(7):2876–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI44555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacGrogan D, D’Amato G, Travisano S, Martinez-Poveda B, Luxan G, Del Monte-Nieto G, et al. Sequential Ligand-Dependent Notch Signaling Activation Regulates Valve Primordium Formation and Morphogenesis. Circ Res. 2016;118(10):1480–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.308077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koenig SN, Bosse K, Majumdar U, Bonachea EM, Radtke F, Garg V. Endothelial Notch1 Is Required for Proper Development of the Semilunar Valves and Cardiac Outflow Tract. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(4) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Accaoui RN, Gould ST, Hajj GP, Chu Y, Davis MK, Kraft DC, et al. Aortic valve sclerosis in mice deficient in endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306(9):H1302–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00392.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Writing Group M. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38–60. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez MA, Selwyn AP. Endothelial function, inflammation, and prognosis in cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2003;115(Suppl 8A):99S–106S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauriah M, Khan F, Lim TK, Elder DH, Godfrey V, Kennedy G, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide is an independent predictor of endothelial function in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;123(5):307–12. doi: 10.1042/CS20110168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okui H, Hamasaki S, Ishida S, Kataoka T, Orihara K, Fukudome T, et al. Adiponectin is a better predictor of endothelial function of the coronary artery than HOMA-R, body mass index, immunoreactive insulin, or triglycerides. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.03.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daiber A, Steven S, Weber A, Shuvaev VV, Muzykantov VR, Laher I, et al. Targeting vascular (endothelial) dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bph.13517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Lu X, Xiang FL, Lu M, Feng Q. Nitric oxide synthase-3 promotes embryonic development of atrioventricular valves. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajamannan NM. Oxidative-mechanical stress signals stem cell niche mediated Lrp5 osteogenesis in eNOS(−/−) null mice. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(5):1623–34. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Q, Song W, Lu X, Hamilton JA, Lei M, Peng T, et al. Development of heart failure and congenital septal defects in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2002;106(7):873–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000024114.82981.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roos CM, Hagler M, Zhang B, Oehler EA, Arghami A, Miller JD. Transcriptional and phenotypic changes in aorta and aortic valve with aging and MnSOD deficiency in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305(10):H1428–39. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00735.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butcher JT, Tressel S, Johnson T, Turner D, Sorescu G, Jo H, et al. Transcriptional profiles of valvular and vascular endothelial cells reveal phenotypic differences: influence of shear stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(1):69–77. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000196624.70507.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller LJ, Lincoln J. Isolation of murine valve endothelial cells. J Vis Exp. 2014;(90) doi: 10.3791/51860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gould RA, Butcher JT. Isolation of valvular endothelial cells. J Vis Exp. 2010;(46) doi: 10.3791/2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satoh M, Fujimoto S, Haruna Y, Arakawa S, Horike H, Komai N, et al. NAD(P)H oxidase and uncoupled nitric oxide synthase are major sources of glomerular superoxide in rats with experimental diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288(6):F1144–52. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00221.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martins-Green M, Petreaca M, Yao M. An assay system for in vitro detection of permeability in human “endothelium”. Methods Enzymol. 2008;443:137–53. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huk DJ, Hammond HL, Kegechika H, Lincoln J. Increased dietary intake of vitamin A promotes aortic valve calcification in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(2):285–93. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peacock JD, Lu Y, Koch M, Kadler KE, Lincoln J. Temporal and spatial expression of collagens during murine atrioventricular heart valve development and maintenance. Dev Dyn. 2008;237(10):3051–8. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donato AJ, Morgan RG, Walker AE, Lesniewski LA. Cellular and molecular biology of aging endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;89(Pt B):122–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller JD, Chu Y, Brooks RM, Richenbacher WE, Pena-Silva R, Heistad DD. Dysregulation of antioxidant mechanisms contributes to increased oxidative stress in calcific aortic valvular stenosis in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(10):843–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee TC, Zhao YD, Courtman DW, Stewart DJ. Abnormal aortic valve development in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2000;101(20):2345–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.20.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paruchuri S, Yang JH, Aikawa E, Melero-Martin JM, Khan ZA, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Human pulmonary valve progenitor cells exhibit endothelial/mesenchymal plasticity in response to vascular endothelial growth factor-A and transforming growth factor-beta2. Circ Res. 2006;99(8):861–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000245188.41002.2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paranya G, Vineberg S, Dvorin E, Kaushal S, Roth SJ, Rabkin E, et al. Aortic valve endothelial cells undergo transforming growth factor-beta-mediated and non-transforming growth factor-beta-mediated transdifferentiation in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(4):1335–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Hinsbergh VW. Targets for pharmacological intervention of endothelial hyperpermeability and barrier function. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;39(4–5):257–72. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV. Endothelial Barrier and Its Abnormalities in Cardiovascular Disease. Front Physiol. 2015;6:365. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spadaccio C, Rainer A, Mozetic P, Trombetta M, Dion RA, Barbato R, et al. The role of extracellular matrix in age-related conduction disorders: a forgotten player? J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12(1):76–82. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balaoing LR, Post AD, Liu H, Minn KT, Grande-Allen KJ. Age-related changes in aortic valve hemostatic protein regulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(1):72–80. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasyanov V, Moreno-Rodriguez RA, Kalejs M, Ozolanta I, Stradins P, Wen X, et al. Age-related analysis of structural, biochemical and mechanical properties of the porcine mitral heart valve leaflets. Connect Tissue Res. 2013;54(6):394–402. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2013.823954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.