Abstract

Contingency management (CM) interventions generally target a single behavior such as attendance or drug use. However, disease outcomes are mediated by complex chains of both healthy and interfering behaviors enacted over extended periods of time. This paper describes a novel multi-target contingency management (CM) program developed for use with HIV positive substance users enrolled in a CTN multi-site study (0049 Project HOPE). Participants were randomly assigned to usual care (referral to health care and SUD treatment) or 6-months strength-based patient navigation interventions with (PN + CM) or without (PN only) the CM program. Primary outcome of the trial was viral load suppression at 12-months post-randomization. Up to $1160 could be earned over 6 months under escalating schedules of reinforcement. Earnings were divided among eight CM targets; two PN-related (PN visits; paperwork completion; 26% of possible earnings), four health-related (HIV care visits, lab blood draw visits, medication check, viral load suppression; 47% of possible earnings) and two drug-use abatement (treatment entry; submission of drug negative UAs; 27% of earnings). The paper describes rationale for selection of targets, pay amounts and pay schedules. The CM program was compatible with and fully integrated into the PN intervention. The study design will allow comparison of behavioral and health outcomes for participants receiving PN with and without CM; results will inform future multi-target CM development.

Keywords: contingency management, behavior targets, HIV disease, health care incentives, substance use disorders

1. Introduction

Contingency management (CM) is a financially-based incentive system designed to increase the frequency of desirable behaviors. This is done by offering tangible rewards (reinforcers) in the form of vouchers, prizes, gift cards or cash, based on objective evidence of the occurrence (or non-occurrence) of a particular defined behavior, which is called the target behavior. The CM approach to motivating behavior and behavior change has received consistent support in many contexts. For example, there are numerous examples where tangible incentives have been used successfully to increase rates of attendance at psychiatric or substance abuse counseling sessions (Corrigan, Bogner, Lamb-Hart, Heinemann & Moore, 2005; Fitzsimons, Tuten, Borsuk, Lookatch & Hanks, 2015; Kidorf, Brooner, Gandotra, Antoine, King, et al., 2013; Ledgerwood, Alessi, Hanson, Godley & Petry, 2008; Milward, Lynskey & Strang, 2014; Petry, Martin & Finoche, 2001; Petry, Martin & Simic, 2005; Petry, Alessi & Ledgerwood, 2012a; Sigmon & Stitzer, 2005; Walker, Rosvall, Field, Allen, McDonald et al., 2010). Another body of literature supports the efficacy of CM interventions for promoting abstinence from drugs of abuse when delivered either in a continuous voucher reinforcement (Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger & Higgins, 2006) or intermittent reinforcement prize draw systems (Benishek, Dougosh, Kirby, Matejkowski, Clements, et al., 2015). CM interventions have also been employed and shown to be efficacious for supporting health-care related behaviors in difficult populations of substance users. This includes interventions focused on patient return for medical test results (Malotte, Rhodes & Mais, 1998; Malotte, Hollingshead & Rhodes, 1999; Thornton, 2008), and for completion of hepatitis B vaccination series (Stitzer, Polk, Bowles & Kosten, 2010; Topp, Day, Wand, Deacon, vanBeck, et al., 2013; Weaver, Metrebian, Hellier, Pilling, Charles, et al., 2014). Incentives have also been shown effective as an intervention to promote medication adherence (DeFulio & Silverman, 2012; Kimmel, Troxel, Loewenstein, Brensinger, Jaskowiak, et al., 2012; Petry, Rash, Byrne, Ashraf & White, 2012b), including adherence to anti-retroviral therapy in HIV positive substance users (Javanbakht, Prosser. Grimes. Weinstein & Farthing, et al., 2006; Rosen, Dieckhaus, McMahon, Valdes, Petry, et al., 2007; Sorensen, Haug, Delucchi, Gruber, Kletter, et al, 2007).

One hallmark of prior CM intervention in addiction and health care has been the use of single behavioral targets. Focus on a single target is very useful in delineating specific behaviors where CM can be effectively applied to promote behavior change. It is notable, however, that in most therapeutic and behavioral health situations, several of the behaviors that have been targeted individually must be enacted in sequence, and repeatedly over lengthy periods of time, in order to achieve a desired long-term outcome. Thus, patients with a chronic health condition must repeatedly contact a physician, receive and fill medication prescriptions then regularly take those medications in order to achieve desired control over their chronic health condition. Follow-through with sequential health care behaviors is problematic for many groups, but this is especially the case for substance users, whose addiction may interfere with health care adherence at any and all points in the sequence. Well documented in this regard are substance users who are HIV positive. Substance use is associated with poor HIV outcomes including reduced viral suppression and accelerated disease progression (Baum, Rafie, Lai, Sales, Page & Campa, 2009; Lucas, 2011; Milloy, Marshall, Kerr, Buxton, Rhodes, et al., 2012; Porter, Babiker, Bhaskaran, Darbyshire, Pezzotti, et al., 2003; Weber, Huber, Rickenbach, Furrer, Elzi, et al., 2009).

A challenge facing the behavioral health community, then, is to devise and investigate CM interventions that can effectively promote sequences of behavior leading to an ultimate desirable health outcome, a goal that has infrequently been pursued to date (Bassett, Wilson, Taaffe, & Freedberg, 2015). A recently completed multi-site CTN study, project HOPE (CTN 0049, Hospital Visit as Opportunity for Prevention and Engagement for HIV-Infected Drug Users), provided the opportunity to develop a novel contingency management intervention designed to aid in the accomplishment of a long-term health goal, namely viral suppression among HIV positive substance users. The study examined the efficacy of a patient navigation intervention delivered with or without a concurrent fully integrated contingency management incentive program, for its ability to engage HIV positive substance users in HIV care while also encouraging them to address their substance use. The CTN study enrolled 801 HIV positive substance users with detectable viral load, a marker indicating that they were out of compliance with standard viral suppressing HIV regimens. Participants were identified and recruited at bedside in hospital settings where they might have come for any reason but were generally hospitalized for an HIV-related condition. Patients who qualified were enrolled into a 12-month study and randomized to one of three 6-month interventions: usual care referral to outpatient HIV and substance abuse services, Patient Navigation combined with incentive-based contingency management (PN + CM) or Patient Navigation (PN) alone. Main outcomes have recently been published (Metsch, Feaster, Gooden, Matheson, Stitzer, et al., 2016)

Patient navigation uses a strengths-based case management approach (Gardner, Metsch, Anderson-Mahoney, Loughlin, del Rio, et al., 2005) that incorporates motivational interviewing methods (Miller & Rollnick, 2013) in working with participants. The PN approach was selected as the background supporting intervention because it has previously been shown to be efficacious in linking persons newly diagnosed with HIV to primary medical care (Gardener, et al., 2005). In the CTN study, navigators helped participants to arrange HIV care and to enter substance use disorder treatment if they desired, to understand their health information, overcome personal barriers to treatment (e.g. transportation and child care) and enlist support from their environment. The CM incentive program was fully integrated into the PN intervention. Since viral load suppression (defined as ≤200 copies/mL) was specified as the primary outcome in the HOPE study, the ultimate question was whether a multi-target CM program would improve this important down-stream health outcome when used in the context of Patient Navigation.

The purpose of the present paper is to describe the multi-target contingency management program that was developed for use in the CTN project HOPE, highlighting the principles and considerations that went into its development. Outcomes examining specific efficacy of the CM intervention components will be available at a later time pending additional secondary data analysis.

2. CM parameters and implementation considerations

Incentive earning amounts

The total amount offered in an incentive program is clearly a critical variable. There have been no systematic methods or guidelines developed for selecting pay amounts in CM studies. Conceptually, pay amounts offered must be sufficiently attractive to motivate participants to undertake the desired behaviors. It is also clear from prior research that the higher the magnitude of reinforcement available, the more effective the CM program will generally be (Higgins, Heil, Dantona, Donham, Matthews & Badger, 2006; Lussier et al., 2006; Petry, Telford, Austin, Nich, Carroll, et al., 2004). Thus, the main constraint on payment in real world settings is the amount that might be supported by local resources and societal opinion, while funding budgets set the constraints in research-supported interventions. One useful precedent for total pay amounts comes from the standard voucher reinforcement program for cocaine abstinence developed by Higgins in which total incentive values in the range of $1000 were used (Higgins, Budney, Bickel, Foerg, Donham & Badger, 1994). With this benchmark in mind, payment schedules were developed that would sum to an amount in the range of $1000–$1500 over the 6-month study. The final total amount that could be earned was $1160. It was anticipated that this total amount would be attractive to participants while in fact averaging to only $193 per month, a very modest sum that may be acceptable to society and health care providers should it prove to be effective.

Incentive earnings distribution

In order to support the main focus of the PN intervention, it was determined that about half the earnings would be allocated to health-related behaviors. As regular contact with the PN was essential for success of the PN intervention, one quarter of earnings was allocated to this goal. The final one-quarter of incentive earnings was allocated to substance use-related goals.

Payment schedules

An important principle incorporated into successful abstinence incentive programs has been the use of escalating schedules of payment such that each successive drug negative sample results in a higher payment than the last, with reset to former lower pay amounts used as a mild penalty in the face of missing or drug positive samples (Higgins et al., 1994). This scheme is designed to engender sustained, rather than sporadic periods of abstinence and has been shown more effective than fixed payment schedules for doing so (Roll, Higgins & Badger, 1996; Roll & Higgins, 2000). The use of escalating pay schedules was deemed essential for the CTN study as the intervention was in effect over a lengthy 6-month time frame. The escalating schedule is designed to sustain desired behaviors over such lengthy periods of time by providing higher value reinforcement at later time points when frequency of behavior tends to decline and internal motivation may be waning (e.g. Stitzer et al., 2010). While an escalation feature was included for virtually all the target behaviors, resets were used more sparingly and in particular were not included in the incentive plan for appointment keeping behaviors. It was, of course, possible and likely that scheduled appointments would be missed, providing an opportunity for use of the reset feature. However, there was concern that resets for missed appointments might be viewed as punishing and counterproductive by reducing motivation to schedule future appointments. Thus, the goal was to reinforce all attended appointments irrespective of their timing and of scheduling history.

Flexible payment delivery timing

In contrast to study outcome assessment activities, which occurred at specified time points after start of the intervention (e.g. 6- and 12-month assessments), none of the targeted activities in the CM program were scheduled in advance to occur at fixed points in time. Indeed, every activity needed to be scheduled in general alignment with protocol guidelines but taking into account local clinical practices as well as clinician and participant availability. For example, eleven PN meetings were specified in the protocol. These were ideally to be delivered with increased spacing over time (i.e. weekly, then biweekly then monthly). Further, some were to be coordinated with the participants’ HIV health care appointments for appointment preparation and review activities. However, there was no fixed schedule for these meetings. Thus, in most cases, a maximum number of incentive payments were specified for the target behavior (e.g. 11 for PN visits) with the understanding that some participants may not be able to earn all the available payments (e.g. for doctor visits) depending on local and individual circumstances.

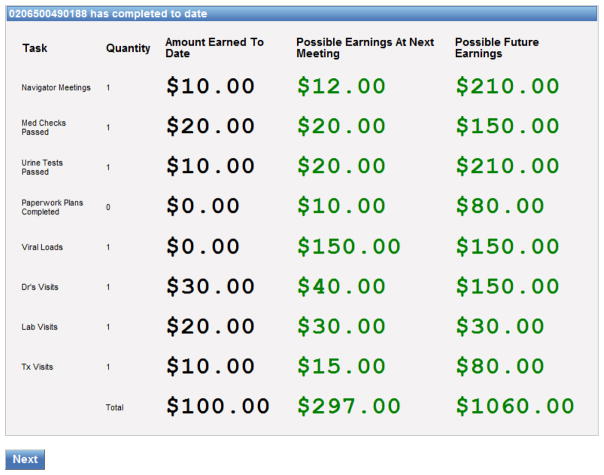

CM management and integration with Patient Navigation

The CM program was fully integrated with PN activities. Navigators directly delivered tangible incentives to complement and emphasize their role in providing social support and encouragement for positive behavioral goals. Because management of a multi-target CM intervention is complex and likely to impact sustainability, a user-friendly computerized management system was developed for PNs’ use in tracking CM targets. At the start of each PN meeting, the navigator entered the participants’ ID into the computer program which stored and updated the participants’ personal target behavior performance and incentive earnings information. As soon as a meeting date and time was entered, the earned incentive payment for that meeting was automatically retrieved from the escalating schedule and displayed. Thus, navigators did not have to keep track of how many previous meetings they had completed with the participant. The program then advanced through screens for each of the remaining targets, ensuring that each target was checked and new information entered as appropriate. For example, if a medical visit or substance use disorder treatment appointment had occurred since the last PN visit, this information would be entered and saved in the tracking system and the appropriate incentive payment assigned. After entries had been made for all the targets, a summary of the incentives earned that day was displayed as well as a screen showing totals earned to date and the remaining incentive amounts available to the participant (see Figure 1). This screen was printed for the participant. Participants could receive earnings immediately or hold them in an account for receipt at a later time. Payment was generally made using cash or gift cards from local retail establishments.

Figure 1.

Example of a final display screen as it appeared in the CM computerized tracking system. This screen displayed at the end of a PN meeting, lists each of 8 incentivized CM targets. Participant ID is shown on the top line. The amount of money earned to date for each target is shown in the first numeric column. Possible earnings at the next meeting (from escalating schedules) is shown in the second numeric column while the final column shows total possible future earnings available for the remaining portion of the 6-month intervention. Addition of numeric columns 1 and 3 adds to the total dollars available for each target, with a total of $1160 across all targets. Please note that labeling and sequence of behavior targets listed here is not the same as that used in the main paper, where targets have been labeled with more clarity and discussed in functional groupings (PN-related, health-related, substance use related).

3. Target behavior considerations

Since the final goal of the CTN study was viral load suppression, one of the first considerations was whether to incorporate incentives for achieving the final desired endpoint. Offering reinforcement for the ultimate health outcome was deemed to be advantageous as this would enhance the saliency of the goal. It was also recognized, however, that reinforcement of this long-term goal was likely to be insufficient in light of the sustained chain of mediating behaviors needed to achieve the goal. Thus, the CM schedule was designed to offer frequent positive reinforcement over time for multiple behaviors likely to mediate (e.g. doctor visits, medication adherence) or interfere (substance use) with achieving the long-term health outcome in addition to incentives for achieving viral load suppression targets.

Eight targets were selected for reinforcement. Two were related to PN visits and activities, four related to health care, and two focused on drug use abatement. The incentive targets are described below and listed in Table 1 along with information about their respective payment amounts and schedules. A detailed explanation of the measurement and implementation rules is available from the authors.

Table 1.

CM Incentive Schedule

| Target Behavior | Maximum Number | Escalation from to ($) | Total $ available |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attend PN meetings | 11 | 10 – 30 | 220 |

| Complete paperwork | PN choice | None specified | 80 |

| Attend doctor visits | 4 | 30 – 60 | 180 |

| Pass medication check | 7 | 20 – 30 | 170 |

| Attend lab visit1 | 2 | 20 – 30 | 50 |

| Achieve viral load suppression2 | 2 | 50 – 100 | 150 |

| Attend SUD treatment3 | 5 | 15 – 20 | 90 |

| Submit negative samples | 11 | 10 – 30 | 220 |

| Total Available | 1160 |

Blood draw prior to doctors visit around weeks 16 and 24

Incentive for 2-log reduction from BL mid-study; full suppression at 6-months

Incentive for initial contact and first four sessions

1. Attend patient navigator meetings (PN related)

The goal of this incentive was to support the PN intervention by encouraging continued regular contact between participants and their patient navigators. As eleven meetings were specified in the protocol, up to eleven incentives could be earned under an escalating schedule for a total of $220 (average of $20 per meeting).

2. Complete paperwork (PN related)

Clinician consultation obtained during study development emphasized the importance of paperwork pre-cursors to services, which might include health insurance or pharmacy support applications. A fixed amount of money ($80) was included in the incentive schema with flexible decision making given to PNs in how and when it would be used with individual patients.

3. Attend doctor visits (Health related)

The goal of this incentive was to support the first step in the care sequence by encouraging continued contact between participants and their HIV medical provider. Navigators played a large role in this process by helping to arrange appointments, accompanying participants to their appointments and briefing and debriefing participants on the process and content of the health care encounters. With this intense PN involvement, it was not certain that incentive payments would have added benefit. However, it was deemed prudent to reinforce this important initial step in the health care sequence in order to evaluate efficacy. It was also anticipated that there would be considerable between-subject variability in the number and spacing of HIV care appointments due in part to variation in local clinical practices. Four incentive payments were included based on the best practices identified by clinician investigators during protocol development with the understanding that not all participants might be able to access the maximum number of incentive payments (e.g. if their doctor elected to see them three rather than four times during the intervention, then only the first three incentive payments would be earned). A total of $180 could be earned under an escalating schedule for keeping up to four appointments. Visits beyond the number specified could of course be made, but would not be reinforced.

4. Pass medication check (Health related)

Regular and sustained ingestion of prescribed medication was clearly the key behavior likely to mediate good outcomes (i.e. viral load suppression) in HIV infected participants. Several approaches to tracking and reinforcing medication adherence were considered, chief among these being a tailored version of directly observed therapy (Tsai, Karasic, Hammer, Charlebois, Ragland, et al., 2013) and MEMS caps, which have been used in several previous studies of HIV medication adherence with substance users (e.g. Rosen et al., 2007; Sorensen et al., 2007). A key consideration here, however, was external validity and sustainability. Study investigators wanted the intervention to be realistic and accessible for future dissemination should it prove effective. Thus it was decided that the medication compliance target would not be direct evidence of pill ingestion but rather evidence that the participant possessed an active prescription. Medication adherence incentives were scheduled at about monthly intervals when prescription renewals were anticipated. An incentive was awarded if the participant brought a pill bottle showing an active prescription to the PN meeting or if the PN could independently validate that an appropriate prescription had been picked up from the pharmacy. Up to $170 could be earned for the medication check target under an escalating schedule. Navigators reviewed self-reported pill taking and discussed with participants the importance of taking their medication as prescribed.

5. Attend lab visit (Health related)

The final health care-related incentive selected was the keeping of appointments for blood draws that were a necessary pre-cursor to viral load assessment. While it was only expected to occur infrequently, this behavior was selected as a target because of its relevance to clinical practice and patient feedback in naturalistic settings. A total of $50 could be earned for two blood draws at mid- and end of treatment.

6. Achieve viral load suppression (Health related)

Two opportunities were provided to receive payment for viral load suppression. The first payment of $50 was available in mid-study with flexible timing to accommodate variability in physician-arranged viral load testing. At this time, the requirement for reinforcement delivery was a 2-log decrease from baseline viral load or viral load ≤ 200 copies/ml. The second payment of $100 was available after the study-specified 6-month sample was tested; at this point, only viral load ≤ 200 copies/ml qualified for incentive payment.

7. Attend substance use disorder treatment (Drug Use related)

Participants in the HOPE study were specifically selected because they had evidence of a substance abuse problem. Patient navigators were encouraged to use their motivational interviewing skills to discuss substance use with participants and explore its role as a barrier in regard to accomplishing HIV care and other life goals. One pathway to addressing substance use would be to enroll in a formal SUD treatment program. Patient navigators helped participants who were willing, to find and enroll in a treatment program, and accompanied them to the intake appointment. In addition, up to $90 in escalating incentive payments were available for attending an intake appointment and the first four visits at the chosen substance abuse treatment clinic.

8. Submit substance negative samples (Drug use related)

While entry into formal substance abuse treatment was considered desirable, the direct reinforcement of substance negative samples (drug negative UA; breathalyzer reading ≤.01mg%) was included as an optional feature of the program to serve as an alternative pathway for promoting abstinence. This novel feature of the incentive program was modeled directly on voucher reinforcement procedures that have been used successfully in the past to encourage drug abstinence (Lussier et al., 2006). However, in an effort to accommodate the protocol and be mindful of the variability that occurs in clinical practice, reinforcement was provided by the PNs based on submission of substance negative samples at their 11 variably spaced visits with participants during the 6-month study. This is in contrast to the frequent (2–3 times per week) testing protocols typical of abstinence-based CM interventions that attempt to detect any and all drug use during the intervention. Drug abstinence incentives were available whether or not the participant chose to enter formal treatment. PNs were equipped to test urine samples on-site using a 10-drug panel (opiate [morphine], oxycodone, methadone, cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, marijuana, benzodiazepines, ecstasy, and barbiturates). Breath alcohol readings were also collected separately. Reinforcement was provided for urine samples that tested negative for six of the ten drugs (opiate, oxycodone, methadone, cocaine, amphetamine and methamphetamine) with a blood alcohol level ≤.01mg% also required. Marijuana was excluded from the incentive plan in order to avoid contested results related to medical marijuana usage and to increase the likelihood that patients could experience success by stopping their use of opioids and stimulants, the illicit substances that have been traditionally targeted in CM abstinence incentive programs and have been shown to inhibit successful progression along the HIV care continuum for substance users (Baum et al., 2009; Lucas, 2011; Porter et al., 2003; Weber et al., 2009). This drug testing option was novel and a potential way to boost motivation for controlling drug use by delivering abstinence reinforcement directly within a patient navigation intervention. Up to $220 could be earned on an escalating schedule for delivering a drug negative urine and negative breath alcohol reading at each of the eleven PN meetings. To encourage sustained periods of abstinence, a reset feature was included in the drug abstinence incentive for missing or positive samples.

4. Significance and future directions

The CTN Project HOPE provided the opportunity to apply basic principles of contingency management intervention, including reinforcement magnitude and scheduling, to development of a unique multi-target CM program that was delivered in the complimentary context of strengths-based patient navigation with the aim of improving participants’ follow through with HIV-related health behaviors. Bassett et al. (2015), recently reviewed other studies that have attempted to improve progression through the HIV treatment cascade using CM approaches. They. cite several studies that incentivized HIV testing uptake or HIV medication adherence but note only two studies that have focused on linkage to and continuation in care using multiple behavioral targets. Solomon, Srikrishnan, Vasudevan, Anand, Kumar, et al (2014) in a study conducted in India, randomized 120 HIV positive drug users to incentive and control arms. Incentive patients could earn up to $68 in vouchers over 12 months (traded for food and household items) for visiting an HIV clinic, initiating antiretroviral therapy and achieving viral suppression. In that study, incentive participants were more likely than controls to initiate ART (45% vs 27%; p=.04) and to attend the clinic (median of 8 vs 3.5 monthly visits out of 12 possible; p=.005). However, these differences in mediating behaviors did not result in differential outcomes on the viral load measure. Another study with negative findings (El-Sadr et al. data from a meeting abstract) offered a $125 coupon to HIV positive patients redeemable if they entered HIV care within 3-months and a $70 gift gift card per quarter if patients were on ART with viral suppression. Both studies used relatively small reinforce amounts and violated the principle of frequent reinforcement by delivering reinforcers at 3-month intervals. The higher pay amounts, frequently delivered reinforers and close monitoring of HIV medication in the present study were likely responsible for positive effects of the incentive intervention in PN + CM versus PN only apparent at the 6-month evaluation including higher rates of PN visit attendance and of self-reported participation in HIV care activities (Metsch et al., 2016).

Design of the CTN study will allow further evaluation of CM effects on specific target behaviors and the role of target behaviors in mediating biological outcomes. Identification of target behaviors that were or were not sensitive to the effects of CM in the context of the intensive supportive PN intervention will provide guidance for future development of multi-target CM programs.

There are many important issues that will need to be addressed in the future development of multi-target interventions. One issue is the relative allocation of monetary reward across incentivized target behaviors. The Project HOPE CM program, with about half (47%) of incentive earnings available for health-related behaviors (doctor and lab visits, medication pickup compliance and viral load bonuses) was consistent with the study’s emphasis health-related behavior goals. However, it is possible that a stronger emphasis on substance use abatement goals may be warranted, supported by higher magnitude and/or more frequently available incentives for drug abstinence. It will clearly be important for future research to explore the impact of relative incentive allocation patterns in multi-target interventions as well as overall pay amounts and schedules. Another issue is implementation context. The CM program was viewed as a compliment the strength-based philosophy and approach of the PN intervention by strengthening the incentive for accomplishing targeted behaviors. Once target behaviors had been enacted, with or without the support of financial incentives, these could then be celebrated and reflected back to participants in the strength-based approach as examples of their own abilities and accomplishments. While this is context is appealing, consideration of alternative implementation contexts would also be valuable in future research.

The project HOPE CM program offers one example of how a multi-target CM intervention might be structured and deployed to impact a critical health outcome in a difficult to treat population- in this case HIV positive substance users. Subsequent data analysis examining the impact of the CM intervention on behavior frequencies will inform the structure and content of future multi-target CM interventions, while considerations of sustainability and cost-effectiveness will be needed to inform implementation policy. Nevertheless, there should be essential lessons learned from the HOPE project that can be translated into both implementation policy and future research that examines components and parameters of incentive-supported health care interventions for difficult populations.

Highlights.

Development of a multi-target contingency management (CM) program is described.

CM complemented a strength-based Patient Navigation (PN) intervention for HIV positive substance users.

Behavioral targets (N = 7) included PN meetings, health care and drug use abatement activities.

Development considerations discussed include reinforcer magnitude, scheduling, and integration with PN activities.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the substantial contribution made by Donald Calsyn, the co-designer of the Project HOPE CM intervention prior to his untimely death. A second major contributor was Leonard Onyiah (Lumen Networks) who designed the computer-based CM management system and spent countless hours in its’ development, trouble shooting and refinement. Finally, we acknowledge the Patient Navigators who worked so capably with all their study participants and seamlessly integrated the CM program into their work. The project HOPE study and manuscript preparation activities were funded under NIDA Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network cooperative agreements UG1DA013034, UG1DA015815, UG1DA013714 and UG1DA013720.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Maxine Stitzer, Email: mstitzer@jhmi.edu.

Timothy Matheson, Email: tim.matheson@sfdph.org.

James Sorensen, Email: james.sorensen@ucsf.edu.

Lauren Gooden, Email: Lkg2129@columbia.edu.

Lisa Metsch, Email: lm2892@columbia.edu.

References

- Bassett IV, Wilson D, Taaffe J, Freedberg KA. Financial incentives to improve progression through the HIV treatment cascade. Current Opinion in HIV and Aids. 2015;10(6):451–63. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page B, Campa A. Crack-cocaine use accelerates HIV disease progression in a cohort of HIV-positive drug users. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;50(1):93–99. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181900129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, Kirby KC, Matejkowski J, Clements NT, Seymour BL, Festinger DS. Prize-based contingency management for the treatment of substance abusers: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1428–36. doi: 10.1111/add.12589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD, Bogner J, Lamb-Hart G, Heinemann AW, Moore D. Increasing substance abuse treatment compliance for persons with traumatic brain injury. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:131–39. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFulio A, Silverman K. The use of incentives to reinforce medication adherence. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55:S86–S94. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons H, Tuten M, Borsuk C, Lookatch S, Hanks L. Clinician-delivered contingency management increases engagement and attendance in drug and alcohol treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;152:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, Loughlin AM, del Rio C, Strathdee S, Sansom SL, Siegal HA, Greenberg AE, Holmberg SD Antiretroviral Treatment and Access Study Study Group. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS (London, England) 2005;19(4):423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg F, Donham R, Badger GJ. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Dantona R, Donham R, Matthews M, Badger GJ. Effects of varying the monetary value of voucher-based incentives on abstinence achieved during and following treatment among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Addiction. 2006;102:271–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht M, Prosser P, Grimes T, Weinstein M, Farthing C. Efficacy of an individualized adherence support program with contingent reinforcement among nonadherent HIV-positive patients: Results from a randomized trial. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2006;5(4):143–150. doi: 10.1177/1545109706291706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, Brooner RK, Gandotra N, Antoine D, King VL, Peirce J, Ghazarian S. Reinforcing integrated psychiatric service attendance in an opioid-agonist program: a randomized and controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;133:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel SE, Troxel AB, Loewenstein G, Brensinger CM, Jaskowiak J, Doshi JA, Laskin M, Volpp K. Randomized trial of lottery-based incentives to improve warfarin adherence. American Heart Journal. 2012;164:268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Godley MD, Petry NM. Contingency management for attendance to group substance abuse treatment administered by clinicians in community clinics. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:517–26. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM. Substance abuse, adherence with anti-retroviral therapy, and clinical outcomes among HIV infected individuals. Life Science. 2011;88:948–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malotte CK, Rhodes F, Mais KE. Tuberculosis screening and compliance with return for skin test reading among active drug users. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;99(5):792–96. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malotte CK, Hollingshead JR, Rhodes J. Monetary versus nonmonetary incentives for TB skin test reading among drug users. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16(3):182–88. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, Matheson T, Stitzer M, Das M, Jain MK, Rodriguez AE, Armstrong WS, Lucas GM, Nijhawan AE, Drainoni ML, Herrera P, Vergara-Rodriguez P, Jacobson JM, Mugavero MJ, Sullivan M, Daar ES, McMahon DK, Ferris DC, Lindblad R, VanVeldhuisen P, Oden N, Castellón PC, Tross S, Haynes LF, Douaihy A, Sorensen JL, Metzger DS, Mandler RN, Colfax GN, del Rio C. Effect of patient navigation with and without financial incentives on viral suppression among hospital patients with HIV infection and substance use. A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2016;316(2):156–170. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Milloy MJ, Marshall BD, Kerr T, Buxton J, Rhodes T, Montaner J, Wood E. Social and structural factors associated with HIV disease progression among illicit drug users: A systematic review. AIDS. 2012;26(9):1049–1063. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835221cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milward J, Lynskey M, Strang J. Solving the problem of non-attendance in substance abuse services. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2014;33:625–36. doi: 10.1111/dar.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Ledgerwood DM. Contingency management delivered by community therapists in outpatient settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012a;122:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Finocche C. Contingency management in group treatment: a demonstration project in an HIV drop-in center. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;21:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Simcic F. Prize reinforcement contingency management for cocaine dependence: integration with group therapy in a methadone clinic. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:354–59. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Rash CJ, Byrne S, Ashraf S, White WB. Financial reinforcers for improving medication adherence: Findings from a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2012b;125(9):888–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Prize reinforcement contingency management for treating cocaine users: how low can we go, and with whom? Addiction. 2004;99:349–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter K, Babiker A, Bhaskaran K, Darbyshire J, Pezzotti P, Porter K, Walker AS CASCADE Collaboration. Determinants of survival following HIV-1 seroconversion after the introduction of HAART. Lancet. 2003;362(9392):1267–74. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, Badger GJ. An experimental comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:495–505. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST. A within-subject comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:103–09. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen MI, Dieckhaus K, McMahon TJ, Valdes B, Petry NM, Cramer J, Rounsaville B. Improved adherence with contingency management. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(1):30–40. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Stitzer ML. use of a low-cost incentive intervention to improve counseling attendance among methadone-maintained patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:253–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon SS, Srikrishnan AK, Vasudevan CK, Anand S, Kumar MS, Balakrishnan P, Mehta SH, Solomon S, Lucas GM. Voucher incentives improve linkage to and retention in care among HIV-infected drug users in Chennai, India. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2014;59(4):589–95. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, Haug NA, Delucchi KL, Gruber V, Kletter E, Batki SL, Tulsky JP, Barnett P, Hall S. Voucher reinforcement improves medication adherence in HIV-positive methadone patients: A randomized trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Polk T, Bowles S, Kosten T. Drug users’ adherence to a 6-month vaccination protocol: Effects of motivational incentives. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;107:76–79. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton RL. The demand for, and impact of, learning HIV status. American Economic Review. 2008;98(5):1829–63. doi: 10.1257/aer.98.5.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp L, Day CA, Wand H, Deacon RM, vanBeek I, Haber PS, Shanahan M, Rodgers C, Maher L. A randomized controlled trial of financial incentives to increase hepatitis B vaccination completion among people who inject drugs in Australia. Preventive Medicine. 2013;57(4):297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Karasic DH, Hammer GP, Charlebois ED, Ragland K, Moss AR, Sorensen JL, Dilley JW, Bangsberg DR. Directly observed antidepressant medication treatment and HIV outcomes among homeless and marginally housed HIV-positive adults: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(2):308–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R, Rosvall T, Field CA, Allen S, McDonald D, Salim Z, Ridley N, Adinoff B. Disseminating contingency management to increase attendance in two community substance abuse treatment centers: lessons learned. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:202–09. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver T, Metrebian N, Hellier J, Pilling S, Charles V, Little N, Poovendran D, Mitcheson L, Ryan F, Bowden-Jones O, Dunn J, Glasper A, Finch E, Strang J. Use of contingency management incentives to improve completion of hepatitis B vaccination in people undergoing treatment for heroin dependence: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;384:153–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R, Huber M, Rickenbach M, Furrer H, Elzi L, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, Bernasconi E, Schmid P, Ledergerber B Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Uptake of and virological response to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected former and current injecting drug users and persons in an opiate substitution treatment programme: The Swiss HIV cohort study. HIV Medicine. 2009;10(7):407–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]