Abstract

Stem cells are essential for both tissue maintenance and injury repair, but many aspects of stem cell biology remain incompletely understood. Recent advances in live imaging technology have allowed the direct visualization and tracking of a wide variety of tissue-resident stem cells in their native environments over time. Results from these studies have helped to resolve long-standing debates about stem cell regulation and function while also revealing previously unanticipated phenomena that raise new questions for future work. Here we review recent discoveries of both types, with a particular emphasis on how stem cells behave and interact with their niches during homeostasis, as well as how these behaviours change in response to wounding.

Introduction

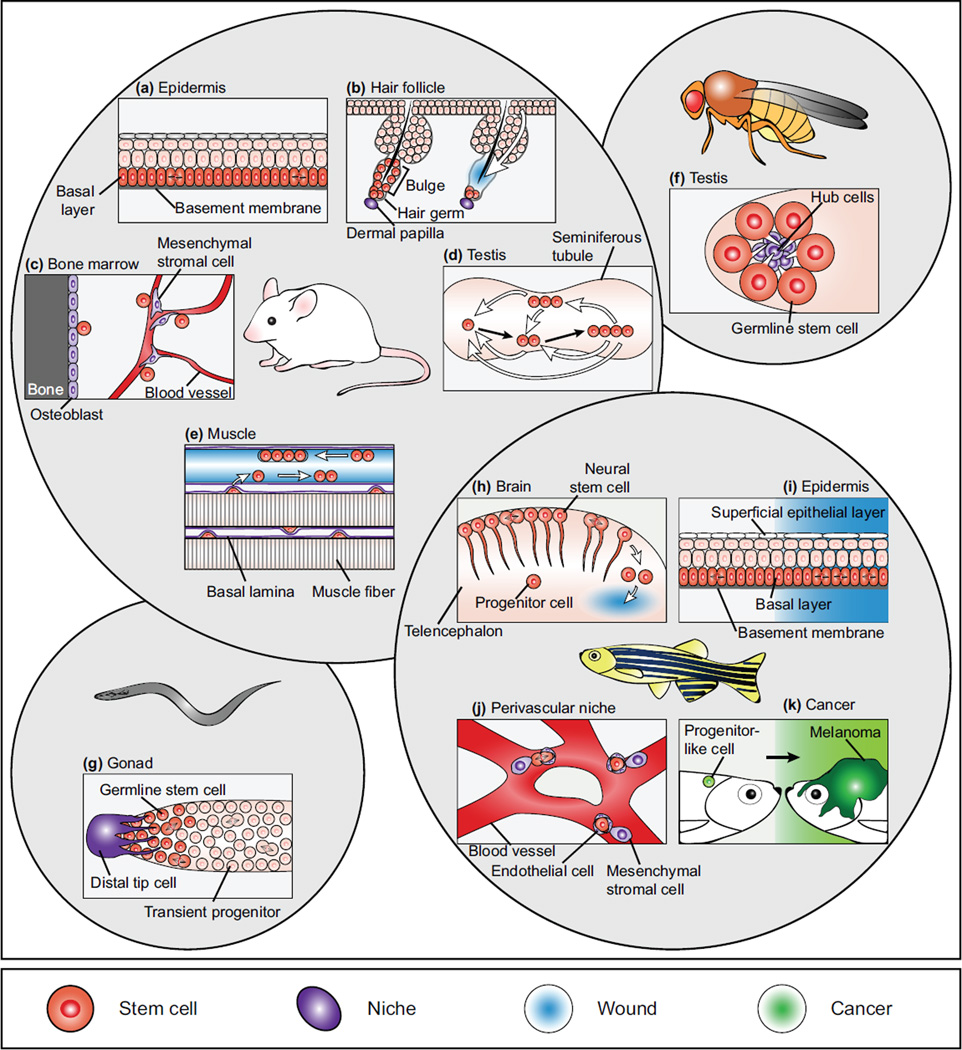

Since their initial identification, stem cells have emerged as the key units fuelling tissue maintenance and repair. Over the years, efforts to characterize these unique cell types and to understand how they sustain lifelong tissue turnover have benefitted from a wide variety of experimental technologies. Of particular significance in recent years has been the advent of various live imaging approaches: the arrival of new imaging modalities such as multiphoton and light sheet microscopy, the improved brightness and versatility of genetically encoded fluorophores, and the development of quantitative strategies for digital image analysis. Together, these technologies have greatly improved our ability to visualize and follow living tissues, cells, and even single molecules over time. The resident stem cells within different tissue types and in many model organisms can now be imaged over time in their natural environments (Figure 1). As with any technological advance, the application of live imaging approaches to the study of stem cells provides two fundamental advantages: the ability to address questions in the field that have previously been unanswerable, and the capacity to discover entirely novel phenomena whose existence have not even been hypothesized. Here we review recent insights of both flavours provided by live imaging of tissue-resident stem cells.

Figure 1.

Recent insights gained from live imaging of tissue-resident stem cells. (a) The underlying basal layer of the mouse epidermis is composed of an equipotent population of stem cells that move upwards to replace differentiated cells lost during homeostasis. (b) In the mouse hair follicle, stem cell behaviours such as proliferation and apoptosis are localized in gradients in relation to the underlying mesenchymal niche. When these stem cells are ablated, they are functionally reconstituted by neighboring epithelial cells. (c) In the mouse bone marrow, HSCs may exist in a peripheral niche composed of osteoblasts and endothelial cells, as well as in additional niches deeper inside the marrow. (d) In the mouse germline, spermatogonial stem cells interconvert between single cell and syncytial states, both of which have the potential to differentiate or self-renew. (e) Upon injury in the mouse muscle, quiescent stem cells become activated and divide and migrate along the longitudinal axis of ECM remnants from previous muscle fibers. (f) In the Drosophila male germline, nanotubes extend from GSCs to their neighboring niche cell, and are required for the transmission of short-range BMP signals from the niche to the stem cells. (g) In the C. elegans germline, the timing of stem and progenitor cell divisions indicate a prominent role for the spindle assembly checkpoint in mitotic progression. (h) In the zebrafish brain during homeostasis, NSCs primarily divide asymmetrically, and occasionally convert directly into committed progenitors. During injury, NSCs can also divide symmetrically to produce to committed progenitor daughters. (i) In the caudal hematopoietic tissue of zebrafish, endothelial cells rapidly remodel around newly arrived HSCs, suggesting an important role for endothelial cell-HSC interactions. (j) In the zebrafish fin, combined mechanisms such as size changes and migration of differentiated cells contribute to the repair of minor wounds, while more severe wounds such as amputation also involve proliferation of underlying basal stem cells. (k) In zebrafish, individual melanocytes within a cancerized field reactivate a neural crest progenitor-like state before progressing into full-growth melanomas. In all images stem/progenitor cells are indicated in orange, niche elements in purple, events that occur during wounding in blue and events associated with cancerous growth in green.

Following stem cell behaviours over time

One of the main ways that live imaging has contributed to the stem cell field is also one of the most conceptually straightforward: it has allowed the behaviour of individual stem cells to be followed over time during the process of tissue turnover. Stem cells have two fundamental roles during tissue maintenance: to replenish the differentiated cell types that are lost during normal turnover, and to renew themselves over time. How these two tasks are achieved, and how they are balanced at the tissue-wide level to achieve homeostasis remain an outstanding question in the field. Traditionally, these problems have been addressed by labelling groups or individual stem cells of interest, followed by fixation and visualization of resulting progeny at later timepoints [1, 2]. More recently, live imaging studies have extended these approaches by enabling the behaviours of individual stem cells to be not just inferred but directly observed as they generate differentiated progeny and self-renew. For example, lineage analysis of fixed samples in the brain has led to conflicting hypotheses about whether individual neural stem cells (NSCs) can self-renew indefinitely [3] or whether they might become depleted over time [4, 5]. In the adult zebrafish brain however, multiphoton imaging has recently allowed individual NSCs to be followed for periods of up to one month [6, **7] (Figure 1H). Because of morphological differences between radial NSCs and their more differentiated non-radial progeny, simple changes in cell shape, number and position can be used to determine how these cells both self-renew and contribute to neurogenesis. Strikingly, such imaging has revealed that while the majority of proliferative NSCs sustain their numbers via asymmetric divisions, other NSCs differentiate directly into neural progenitors [**7], supporting the hypothesis that individual NSCs can become depleted over time. Whether this type of depletion eventually occurs in all NSCs, and whether similar depletion events also take place in the mammalian brain, remain questions for future work.

In the mouse epidermis, the proliferation of stem cells in the underlying basal layer must precisely balance the number of terminally differentiated cells lost during normal homeostasis (Figure 1A). Over the past 10 years, various analyses of large numbers of fixed clonal samples has suggested that this balance is achieved by a population of basal cells that divide primarily in an asymmetric fashion to produce one daughter cell fated to remain in the basal layer and one fated to move upwards and differentiate [8–10]. These studies also argued that a minority of basal cell divisions were asymmetric, with both daughter cells acquiring the same fate, and that these symmetric divisions were infrequent and stochastic, such that no basal progenitor was truly immortal. Recent work combining live imaging with novel genetic labeling approaches has built on these earlier studies by allowing individual cell fate choices within labelled clones to be resolved over time [**11]. Analysis of these data has confirmed earlier fixed clonal analysis showing that the epidermis is maintained by a population of equipotent stem cells. However this work has also demonstrated that that there is in fact no bias towards symmetric or asymmetric divisions, confirming a model initially proposed over 50 years ago[12]. Unexpectedly, daughter cells produced by a basal cell divisions are often correlated not only in their fate, but also in the timing in which this fate is executed, leading to frequent symmetric divisions and suggesting that cellular behaviours may be coordinated by signals from the surrounding tissue [**11]. Such coordination could allow the epidermis as a whole to meet the changing demands of its environment while still balancing the processes of cell production and cell loss over time.

There are also situations in which the live imaging of stem cells has revealed highly unexpected behaviors. A prime example of this is in the mouse testis, where the stem cell differentiation was believed to follow a stereotyped path from stem cell to syncytial chains of committed cells and finally to differentiated cells that undergo spermatogenesis [13]. Live imaging of both single cells and syncytial chains however has recently revealed that these two states are interconvertible: syncytial chains can fragment into single cells and single cells can undergo incomplete divisions to generate syncytial chains [**14, 15] (Figure 1D). Moreover, cellular state does not correlate precisely with cell potential: both single cells and syncytia contain subpopulations with higher or lower biases toward differentiation. Thus, the ability to follow individual spermatogonial stem cells over time in this context has revealed a striking and unanticipated level of heterogeneity within this population. Visualization of unexpected behaviours has not been limited to the spermatogonial system however. In the mouse, other examples include phagocytic epithelial clearance, oriented cell divisions and morphological rearrangements in the hair follicle [*16, 17], and wide-ranging migratory behaviors in hematopoietic stem cells after exposure to infectious agents [*18]. In the worm, live imaging has been used to demonstrate an unexpectedly prominent role for the spindle assembly checkpoint during division of germline stem and progenitor cells [**19] (Figure 1G). Such observations have contributed multiple levels of insight into the cellular mechanisms by which stem cell populations maintain tissues over time and raise exciting new questions for further study.

Imaging dynamic stem cell-niche interactions

In addition to allowing the direct observation of stem cells themselves, in vivo imaging approaches also provide the ability to observe the interplay between these cells and their surroundings. The concept of specialized local microenvironments that support stem cell maintenance was proposed over 40 years ago [20]. Called niches, these microenvironments were first demonstrated experimentally in the C. elegans and Drosophila model systems [21, 22], but several recent live imaging studies have revealed new insights into both the composition of different niche environments and the mechanisms by which they support their resident stem cell populations.

The ability to preserve normal tissue architecture during microscopy can help address longstanding questions about the nature of the niche itself. In the case of the mammalian hematopoietic system, many studies have attempted to determine which of two cellular elements in the bone marrow, osteoblasts or endothelial cells, might be acting as a niche for long-term hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [23]. Attempts to observe spatial relationships between hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and these two components have previously relied on thin histological sections, where elusive HSCs have been difficult to capture in high numbers [24, 25]. Pioneering live imaging work that was able to capture labelled HSCs within their normal 3-dimensional tissue environment, has helped to address this question by suggesting that HSC niches may in fact contain both osteoblast and vascular components that are closely apposed [26] (Figure 1C). This early work has been complemented by recent live visualization of oxygen levels and blood flow in the intact bone marrow, which indicates that the vasculature previously identified as more closely associated with osteoblasts is in fact primarily arterial [*27]. Together these studies have identified one potential HSC niche in the peripheral bone marrow that is composed of arteries and bone. It is important to note that current multiphoton technology is unable to penetrate into the deepest regions of the bone marrow, and so approaches such as the tissue-clearing of fixed samples will still serve as an important complementary approach to investigate potential HSC niches that occur further from the surface [28]. Finally, it will be important for future live imaging studies to investigate the behaviours and niche interactions of other hematopoietic cell populations such as short-term HSCs and multipotent progenitors, which likely sustain the bulk of day-to-day hematopoiesis in adult animals [29, 30].

In situations where the cellular composition of a particular niche is well understood, visualization of nearby stem cell behaviours can also provide insight into niche function. By performing time lapse imaging of stem cells in the mouse hair follicle during both its growth and regression phases, a number of cellular phenomena can be observed to be spatially organized with respect to their distance from the adjacent mesenchymal niche (the dermal papilla, or DP). In particular, cell divisions during follicle growth [17] and cell death during regression [16] are both initiated in cells closely adjacent to the DP, suggesting that such behaviours may be niche-dependent (Figure 1C). In confirmation of this, precisely timed genetic or laser-mediated ablation of the DP interferes with division during the growth phase and/or death during the regression phase [16, 17, 31]. Strikingly, live imaging has identified a similar phenomenon in the mouse intestine: the cells located more centrally within the intestinal crypt niche are biased towards self-renewal, while those located towards the niche periphery are more likely to differentiate [32].

In many tissues, questions about how specific niche components are able to influence the behaviour of their resident stem cells remain outstanding. Expression profiling and genetic approaches have succeeded in identifying many niche-produced molecular cues, but understanding how these cues are transmitted with in a tissue, and what specific stem cell behaviours they influence, can be aided significantly by the use of live imaging approaches. Despite knowledge of the molecular signals produced by niche hub cells in the Drosophila male germline, how these signals are conveyed exclusively to specific germline stem cell (GSC) neighbours has remained a mystery. Recent live imaging studies using an explant system have revealed the presence of microtubule-based nanotubes, previously undetectable in fixed tissue, that extend from GSCs into neighboring hub cells [33] (Figure 1F). A combination of genetics and live imaging of a labelled BMP receptor that can be seen moving along these structures indicates that nanotubes are essential for the transmission of at least one short-range signal from the niche to neighboring GSCs. Future work will be required to determine whether similar microtubule-based structures, perhaps in combination with the more long-distance, actin-based filopodia that have been described in developmental contexts [34, 35], are important in other systems where specific and localized signaling is essential for maintaining proper stem cell numbers.

In addition to the transmission of secreted signals, live imaging has been able to capture other unexpected niche behaviours that likely play a role in proper stem cell function. In both the embryonic caudal hematopoietic tissue of zebrafish and the fetal liver of mouse, endothelial niche cells can be observed rapidly remodelling to surround newly arrived HSCs [**36] (Figure 1J). The observation that HSCs remain inside these structures for the duration of further imaging suggests that dynamic endothelial remodelling may serve to retain stem cells in a permissive tissue environment. The molecular mechanisms by which endothelial cells are able to remodel in response to HSCs, how they retain these cells over time, and what specific influences they may have on HSC function have yet to be demonstrated. Regardless, the ability to observe dynamic niche cell behaviours in real time provides another layer of insight into niche-stem cell interactions.

Imaging dynamic stem cell behaviours during injury repair

In addition to normal homeostatic maintenance, tissues must also be able to mend themselves after sustaining damage, and the activity of stem cells is to fueling this repair process. The need for wound repair can rapidly and dramatically alter cellular behaviours within a tissue. Such changes can be difficult to fully capture using static analysis, but recent live imaging studies have helped to reveal real-time behaviors and functional roles of stem cells during the repair process.

When cells are damaged or lost due to injury, this loss must be somehow compensated for. To what extent the replacement of lost cells after wounding is fueled directly by stem cell proliferation, and how alternative cellular mechanisms might instead contribute to repair remain largely unknown. Recent work combining clonal fate mapping, a live readout of stem cell proliferation, and the ability to revisit regenerating tissues over time has revealed that in the zebrafish fin, different types of injury can affect the extent to which stem cells proliferate [**37] (Figure 1I). In response to scale exfoliation, a mild injury that removes only overlying differentiated superficial epithelial cells (SECs), underlying basal stem cells in the skin remain largely quiescent. The surface left devoid of SECs is instead re-covered by a combination of cell expansion, cell migration, and an accelerated rate of differentiation. It is only in response to a more significant injury, fin amputation, that basal stem cells can be observed proliferating to fuel tissue repair. Thus the type of injury sustained can affect how a tissue and its resident stem cells initiate the process of repair.

In situations where stem cells are known to proliferate in response to injury, questions still remain about how these divisions help to rebuild a functional tissue. Is a simple increase in proliferation rate sufficient to fuel tissue repair, or do stem cells need to switch from their normal modes of division to produce different types or amounts of progeny? How does the spatial orientation of these divisions affect the organization of the tissue that is being rebuilt? Timelapse imaging of the zebrafish brain after stab wounding has revealed that in this system, injury not only increases the number of NSCs undergoing proliferation, but causes NSCs to divide symmetrically to produce two more differentiated daughter cells, a behaviour not normally seen during homeostasis [**7] (Figure 1H). These unanticipated symmetric divisions help explain how the NSC population is able to rapidly replace the many differentiated neurons lost to injury. In the mouse muscle, where stem cells are known to exit from their quiescent state and proliferate in response to injury, recent in vivo imaging has revealed how these divisions help rebuild a properly organized tissue architecture. Strikingly, and in contrast to previous data obtained from in vitro studies, muscle injury causes stem cells to both divide and migrate longitudinally along extracellular matrix (ECM) remnants from previous muscle fibers (Figure 1E) [**38]. Experimentally re-orienting these ECM fibers caused new muscle fibers to be regenerated in a disorganized manner, demonstrating the essential interplay between existing tissue architecture, stem cell behaviour, and proper regeneration.

In certain severe situations, wounding may deplete not only functional differentiated cells within a tissue but also its resident stem cell population. How might a tissue cope with this more extreme form of injury? Recently, this question has been addressed in the mouse hair follicle. Because of its highly compartmentalized nature, stem cells within the follicle can be ablated in a highly specific manner, leaving other regions of this organ unaffected [**39]. Strikingly, hair follicles depleted of their stem cells, when revisited at later timepoints, are still able to undergo normal cycling behaviour. Lineage tracing experiments reveal that the lost stem cell population can be functionally reconstituted by cells from other epithelial compartments that normally do not participate in hair follicle cycling [**39] (Figure 1B). This rapid exchange of cells between cycling and non-cycling regions of the skin has not been reported to occur during homeostasis [40]. These results indicate that a specific stem cell population is dispensable for hair follicle regeneration, and instead that epithelial cells can display a high degree of plasticity in response to injury.

Imaging cancer initiation and growth

Live imaging is also providing new opportunities to follow both the early stages and later progression of cancerous growths in a number of tissue types. Of particular interest in recent years has been the question of whether tumour growth is sustained by stem cell-like subpopulations (cancer stem cells, CSC). Genetic labelling and lineage tracing has demonstrated the presence of CSCs in solid tumours such as intestinal adenomas and skin papillomas [41, 42], but questions remain about the behavior of CSC-derived clones over time. A recent study has combined live imaging with multicolor labelling to follow the temporal dynamics of multiple CSCs clones during different stages of mammary tumor progression [43]. When labelling is induced early in tumour formation, only small numbers of clones can be seen making up the bulk of the tumour at later stages, suggesting the presence of CSCs in mammary tumours. Interestingly, at later stages of tumour development there are dynamic changes to the size of individual clones over time, indicating that CSC state is plastic and can be gained or lost over time.

Live imaging also represents and opportunity to visualize the earliest events of tumour initiation and growth, which have previously been almost impossible to capture. Recently, live imaging of zebrafish transgenic for Crestin:EGFP, a marker expression normally only in neural crest progenitors (NCP) during development, has shown that individual cells re-enter the NCP-state before developing into melanoma [**44] (Figure 1K). Thus the ability to capture the very first steps of tumour development has indicated that re-entry into a progenitor state is key for oncogenic progression, consistent with previous findings derived from transcriptional profiling of another tumour type, basal cell carcinomas [45].Live imaging has also helped to reveal one possible mechanism that may allow small numbers of mutant cells to form large, heterogeneous tumours: following groups of cells genetically hyper-activated for Wnt signaling has shown that these cells are able to recruit their wild-type neighbors into nascent growths [46]. Following early stages of tumour development in other systems will reveal whether this type of phenomenon might be a conserved mechanism for tumour progression.

Conclusions

Over the course of only the past few years, live imaging approaches have yielded exciting new insights into the regulation and function of stem cells across a wide range of tissue types. In addition to helping to resolve long standing questions in the field, multiple groups have been able to observe phenomena entirely unanticipated by previous approaches, revealing new levels of complexity and novel dynamics important for tissue maintenance and repair. In the future it will be important to build on these advances by understanding the molecular mechanisms that underpin stem cell and niche biology. Fluorescent reporters that faithfully reflect transcriptional changes, signalling status and molecular interactions within stem cells and their surrounding environment will be an essential next step towards this aim [47]. The use of non-neuronal optogenetic tools, which have already been shown to provide spatiotemporal control over some molecular interactions in vivo [48, 49], will allow molecular events that can be visualized with reporters to be precisely manipulated to dissect their specific roles. In combination with existing live imaging approaches, these types of tools will provide yet another level of insight into how stem cells maintain tissues over time.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Xin, E. Marsh and A. Klein for their valuable comments on the manuscript. This work is supported by The New York Stem Cell Foundation and grants to V.G. by the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Foundation and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease (NIAMS), NIH, grants 5R01AR063663-04; and 1R01AR067755-01A1. S.P. is supported by the CT Stem Cell Grant 14-SCA-YALE-05. K.C. is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Postdoctoral Fellowship. V.G is a New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alcolea MP, Jones PH. Lineage analysis of epidermal stem cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a015206–a015206. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanpain C, Simons BD. Unravelling stem cell dynamics by lineage tracing. Nature Publishing Group. 2013;14:489–502. doi: 10.1038/nrm3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonaguidi MA, Wheeler MA, Shapiro JS, Stadel RP, Sun GJ, Ming G-L, Song H. In vivo clonal analysis reveals self-renewing and multipotent adult neural stem cell characteristics. Cell. 2011;145:1142–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Encinas JM, Michurina TV, Peunova N, Park J-H, Tordo J, Peterson DA, Fishell G, Koulakov A, Enikolopov G. Division-coupled astrocytic differentiation and age-related depletion of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:566–579. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calzolari F, Michel J, Baumgart EV, Theis F, Götz M, Ninkovic J. Fast clonal expansion and limited neural stem cell self-renewal in the adult subependymal zone. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:490–492. doi: 10.1038/nn.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dray N, Bedu S, Vuillemin N, Alunni A, Coolen M, Krecsmarik M, Supatto W, Beaurepaire E, Bally-Cuif L. Large-scale live imaging of adult neural stem cells in their endogenous niche. Development. 2015;142:3592–3600. doi: 10.1242/dev.123018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barbosa JS, Sanchez-Gonzalez R, Di Giaimo R, Baumgart EV, Theis FJ, Götz M, Ninkovic J. Neurodevelopment. Live imaging of adult neural stem cell behavior in the intact and injured zebrafish brain. Science. 2015;348:789–793. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2729. This study uses multiphoton microscopy to track individual NSCs in the zebrafish brain over time. During homeostasis, NSC numbers gradually decrease due to occasional direct differentiation events. In response to injury, some NSCs take on a new division mode which generated two committed progenitor daughter cells, depleting the stem cell population much more quickly. This work has helped address the question of how the neurogenic ability of the brain decreases over time.

- 8.Mascré G, Dekoninck S, Drogat B, Youssef KK, Broheé S, Sotiropoulou PA, Simons BD, Blanpain C. Distinct contribution of stem and progenitor cells to epidermal maintenance. Nature. 2012;489:257–262. doi: 10.1038/nature11393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayton E, Doupé DP, Klein AM, Winton DJ, Simons BD, Jones PH. A single type of progenitor cell maintains normal epidermis. Nature. 2007;446:185–189. doi: 10.1038/nature05574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doupé DP, Klein AM, Simons BD, Jones PH. The ordered architecture of murine ear epidermis is maintained by progenitor cells with random fate. Developmental Cell. 2010;18:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rompolas P, Mesa KR, Kawaguchi K, Park S, Gonzalez DG, Brown S, Boucher J, Klein AM, Greco V. Spatiotemporal coordination of stem cell commitment during epidermal homeostasis. Science. 2016;352:1471–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7012. This study combines a novel genetic labelling approach with live tissue revisits to follow individual epidermal stem cells in the basal layer throughout their lifetimes, from birth to death, and to construct clonal lineage trees over multiple generations. Large scale analyses reveal that the basal layer is composed of an equipotent populations of stem cells, and in contrast to previous hypothesis based on fixed clonal samples, these cells show no bias towards symmetric or asymmetric divisions.

- 12.P M-PJ, Leblond CP. Mitosis and differentiation in the stratified squamous epithelium of the rat esophagus. Am. J. Anat. 1965;117:73–87. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001170106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huckins C. The spermatogonial stem cell population in adult rats. I. Their morphology, proliferation and maturation. Anat. Rec. 1971;169:533–557. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091690306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hara K, Nakagawa T, Enomoto H, Suzuki M, Yamamoto M, Simons BD, Yoshida S. Mouse spermatogenic stem cells continually interconvert between equipotent singly isolated and syncytial states. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:658–672. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.019. Live imaging of the mouse male germline reveals the previously unanticipated finding that spermatogonical stem cells can exist as both single cells and as syncytia, and that these two states are dynamically interconvertible during normal homeostasis.

- 15.Nakagawa T, Sharma M, Nabeshima YI, Braun RE, Yoshida S. Functional Hierarchy and Reversibility Within the Murine Spermatogenic Stem Cell Compartment. Science. 2010;328:62–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1182868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mesa KR, Rompolas P, Zito G, Myung P, Sun TY, Brown S, Gonzalez DG, Blagoev KB, Haberman AM, Greco V. Niche-induced cell death and epithelial phagocytosis regulate hair follicle stem cell pool. Nature. 2015;522:94–97. doi: 10.1038/nature14306. Live imaging of the mouse hair follicle has revealed a number of previously unanticipated insights into how this organ undergoes cyclical regression: that dying cells are phagocytosed by their epithelial neighbors within the follicle, that these events occur in a gradient with respect to the neighboring DP niche, and that ablation of the DP prevents death from occurring.

- 17.Rompolas P, Deschene ER, Zito G, Gonzalez DG, Saotome I, Haberman AM, Greco V. Live imaging of stem cell and progeny behaviour in physiological hair-follicle regeneration. Nature. 2012;487:496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature11218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rashidi NM, Scott MK, Scherf N, Krinner A, Kalchschmidt JS, Gounaris K, Selkirk ME, Roeder I, Celso Lo C. In vivo time-lapse imaging shows diverse niche engagement by quiescent and naturally activated hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2014;124:79–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-534859. This study demonstrates for the first time how HSCs in their native niche alter their behaviors when exposed to an infectious agent. The increased HSC migratory behaviors documented in this work likely correspond to changes in HSC engraftment ability and/or function.

- 19. Gerhold AR, Ryan J, Vallée-Trudeau J-N, Dorn JF, Labbé J-C, Maddox PS. Investigating the regulation of stem and progenitor cell mitotic progression by in situ imaging. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1123–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.054. Careful live imaging analysis of mitotic progression in C. elegans stem and progenitor cells, combined with genetic approaches, demonstrated an unexpectedly prominent role for the spindle assembly checkpoint in these cells. Furthermore, changes to organismal physiology can alter mitotic progression by acting through this checkpoint mechanism.

- 20.Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood cells. 1978;4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimble J. Alterations in cell lineage following laser ablation of cells in the somatic gonad of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1981;87:286–300. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie T, Spradling AC. A niche maintaining germ line stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Science. 2000;290:328–330. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;505:327–334. doi: 10.1038/nature12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiel MJ, Radice GL, Morrison SJ. Lack of Evidence that Hematopoietic Stem Cells Depend on N-Cadherin-Mediated Adhesion to Osteoblasts for Their Maintenance. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:204–217. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celso Lo C, Fleming HE, Wu JW, Zhao CX, Miake-Lye S, Fujisaki J, Côté D, Rowe DW, Lin CP, Scadden DT. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2009;457:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spencer JA, Ferraro F, Roussakis E, Klein A, Wu J, Runnels JM, Zaher W, Mortensen LJ, Alt C, Turcotte R, et al. Direct measurement of local oxygen concentration in the bone marrow of live animals. Nature. 2014;508:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature13034. Live measurements of local oxygen tension within the intact mouse bone marrow reveal localized differences in oxygen concentration: deeper regions are more hypoxic, while more peripheral regions are less hypoxic. How these different oxygen levels might relate to HSC regulation are exciting questions for future work.

- 28.Acar M, Kocherlakota KS, Murphy MM, Peyer JG, Oguro H, Inra CN, Jaiyeola C, Zhao Z, Luby-Phelps K, Morrison SJ. Deep imaging of bone marrow shows non-dividing stem cells are mainly perisinusoidal. Nature. 2015;526:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature15250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Busch K, Klapproth K, Barile M, Flossdorf M, Holland-Letz T, Schlenner SM, Reth M, Höfer T, Rodewald H-R. Fundamental properties of unperturbed haematopoiesis from stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2015;518:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature14242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun J, Ramos A, Chapman B, Johnnidis JB, Le L, Ho Y-J, Klein A, Hofmann O, Camargo FD. Clonal dynamics of native haematopoiesis. Nature. 2014;514:322–327. doi: 10.1038/nature13824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chi W, Wu E, Morgan BA. Dermal papilla cell number specifies hair size, shape and cycling and its reduction causes follicular decline. Development. 2013;140:1676–1683. doi: 10.1242/dev.090662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritsma L, Ellenbroek SIJ, Zomer A, Snippert HJ, de Sauvage FJ, Simons BD, Clevers H, van Rheenen J. Intestinal crypt homeostasis revealed at single-stem-cell level by in vivo live imaging. Nature. 2014;507:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature12972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Inaba M, Buszczak M, Yamashita YM. Nanotubes mediate niche-stem-cell signalling in the Drosophila testis. Nature. 2015;523:329–332. doi: 10.1038/nature14602. Live imaging of the Drosophila testis has revealed microtubule based structures that extend from GSCs to their neighboring niche cells and that are essential from the transmission of BMP signals from the niche. This is the first study to describe a mechanism by which short range signals from the niche are targeted specifically to stem cells.

- 34.Fairchild CL, Barna M. Specialized filopodia: at the “tip” of morphogen transport and vertebrate tissue patterning. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;27C:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kornberg TB. Cytonemes and the dispersion of morphogens. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2014;3:445–463. doi: 10.1002/wdev.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tamplin OJ, Durand EM, Carr LA, Childs SJ, Hagedorn EJ, Li P, Yzaguirre AD, Speck NA, Zon LI. Hematopoietic stem cell arrival triggers dynamic remodeling of the perivascular niche. Cell. 2015;160:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.032. This study uses live imaging to demonstrate a remarkable dynamic interaction between HSCs and endothelial niche cells in the zebrafish caudal hematopoietic tissue. The endothelial remodeling observed in zebrafish is also conserved in the mouse fetal liver, suggesting that it may be a key mechanism mediating HSC development or function.

- 37. Chen C-H, Puliafito A, Cox BD, Primo L, Fang Y, Di Talia S, Poss KD. Multicolor Cell Barcoding Technology for Long-Term Surveillance of Epithelial Regeneration in Zebrafish. Developmental Cell. 2016;36:668–680. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.017. This study demonstrates that the type of injury sustained by a tissue can affect how both differentiated cells and stem cells participate in repair. In the zebrafish fin, it is only after a severe injury like amputation that stem cells are mobilized to proliferate and contribute to the healing process.

- 38. Webster MT, Manor U, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Fan C-M. Intravital Imaging Reveals Ghost Fibers as Architectural Units Guiding Myogenic Progenitors during Regeneration. Stem Cell. 2016;18:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.11.005. This study reveals how existing tissue architecture can instruct stem cell behaviors during wound repair. In the mouse muscle, remnants of ECM from muscle fibers previously lost to injury guide the division and migration of activated stem cells. These types of oriented behaviors had not been appreciated from previous in vitro and 2D studies.

- 39. Rompolas P, Mesa KR, Greco V. Spatial organization within a niche as a determinant of stem-cell fate. Nature. 2014;502:513–518. doi: 10.1038/nature12602. In this paper, clonal labelling and revisits of individual cells at different positions within the hair follicle reveal that stem cell position correlates with stem cell fate. Moreover when the stem cell population is completely ablated, neighboring epidermal cells can functionally reconstitute the stem cell niche. This is the first demonstration of the high degree of flexibility that can exist within a tissue upon damage to its stem cell population.

- 40.Ito M, Liu Y, Yang Z, Nguyen J, Liang F, Morris RJ, Cotsarelis G. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nat Med. 2005;11:1351–1354. doi: 10.1038/nm1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, van den Born M, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science. 2012;337:730–735. doi: 10.1126/science.1224676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Driessens G, Beck B, Caauwe A, Simons BD, Blanpain C. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature. 2012;488:527–530. doi: 10.1038/nature11344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zomer A, Ellenbroek S, Ritsma L, Beerling E. Brief report: intravital imaging of cancer stem cell plasticity in mammary tumors. Stem Cells. 2013;31:602–606. doi: 10.1002/stem.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaufman CK, Mosimann C, Fan ZP, Yang S, Thomas AJ, Ablain J, Tan JL, Fogley RD, van Rooijen E, Hagedorn EJ, et al. A zebrafish melanoma model reveals emergence of neural crest identity during melanoma initiation. Science. 2016;351:aad2179. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2197. This study uses zebrafish live imaging combined with a fluorescent marker of embryonic neural crest to capture melanoma formation at its very earliest stages and to demonstrate that single cells transition into melanomas by first reverting to a neural crest progenitor state.

- 45.Youssef KK, Van Keymeulen A, Lapouge G, Beck B, Michaux C, Achouri Y, Sotiropoulou PA, Blanpain C. Identification of the cell lineage at the origin of basal cell carcinoma. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:299–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deschene ER, Myung P, Rompolas P, Zito G, Sun TY, Taketo MM, Saotome I, Greco V. β-Catenin activation regulates tissue growth non-cell autonomously in the hair stem cell niche. Science. 2014;343:1353–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.1248373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Endele M, Schroeder T. Molecular live cell bioimaging in stem cell research. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012;1266:18–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guglielmi G, Barry JD, Huber W, De Renzis S. An Optogenetic Method to Modulate Cell Contractility during Tissue Morphogenesis. Developmental Cell. 2015;35:646–660. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buckley CE, Moore RE, Reade A, Goldberg AR, Weiner OD, Clarke JDW. Reversible Optogenetic Control of Subcellular Protein Localization in a Live Vertebrate Embryo. Developmental Cell. 2016;36:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]