Abstract

Objectives

To identify hospice and patient characteristics associated with the use of continuous home care (CHC), and to examine the associations between CHC utilization and hospice disenrollment or hospitalization after hospice enrollment.

Methods

Using 100% fee-for-service Medicare claims data for beneficiaries aged 66 years or older who died between July and December 2011, we identified the percentage of hospice agencies in which patients used CHC in 2011 and determined hospice and patient characteristics associated with use of CHC. Using multivariable analyses, we examined the associations between CHC utilization and hospice disenrollment and hospitalization after hospice enrollment, adjusted for hospice and patient characteristics.

Results

Only 42.7% of hospices (1,533 out of 3,592 hospices studied) provided CHC to at least 1 patient during the study period. Patients enrolled with for-profit, larger, and urban located hospices were more likely to use CHC (P-values < 0.001). Within these 1,533 hospices, only 11.4% of patients used CHC. Patients who were white, had cancer, and had more comorbidities were more likely to use CHC. In multivariable models, compared with patients who did not use CHC, patients who used CHC were less likely to have hospice disenrollment (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 0.21, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.19-0.23) and less likely to be hospitalized after hospice enrollment (AOR: 0.37, 95% CI: 0.34-0.40).

Conclusions

Although a minority of patients uses CHC, such services may be protective against hospice disenrollment and hospitalization after hospice enrollment.

Keywords: Hospice, Continuous home care, Hospice disenrollment, End-of-life care

Introduction

Hospice has been found to be an effective model of care for addressing the palliative care needs of patients with limited life expectancy.1 However, little research has been conducted on the level of hospice services received and its association with patterns of end-of-life care. Hospice includes 4 levels of care: routine home care, inpatient respite care, general inpatient care, and continuous home care (CHC).2 Among these 4 levels of care, CHC is substantially more expensive and resource-intensive than the other 3 levels of care,3 as it involves provision of a minimum of 8 hours of licensed nursing care per day in the home.4,5 Previous literature has indicated that about 45% of hospice programs provide CHC services,6,7 and CHC constitutes approximately 1% of hospice enrollee care days,8 with African American or unmarried decedents being less likely to use CHC than white or married decedents.9

Although the primary goal of CHC is to help hospice enrollees stay at home, evidence regarding the impact of CHC on end-of-life care transitions is limited. Only 2 studies have examined the association between use of CHC and subsequent end-of-life care.10,11 One study reported that patients using CHC were less likely to be transferred from home to another location before death,10 and the other study reported that patients using CHC were less likely to die in an inpatient hospice setting.11 Both studies were conducted with small, selected samples of hospices; furthermore, we could find no studies that have examined the association between CHC and hospice disenrollment or hospitalization after hospice enrollment. Given the paucity of nationally representative studies and limited outcomes examined, the link between CHC use and subsequent end-of-life care transitions remains largely unknown.

Accordingly, we sought to estimate the use of CHC nationally as well as identify hospice and patient characteristics associated with the likelihood of CHC use. We further sought to determine the associations between CHC use and hospice disenrollment and hospitalization after hospice enrollment. Findings from this study may provide novel insight and be useful for generating a more comprehensive understanding of the potential benefits of CHC, particularly as hospice disenrollment has been linked with significantly increased costs at the end of life.12-16

Methods

Study design and sample

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries older than 66 years who died in 2011. Using decedent hospice claims data, we identified hospice providers that submitted at least 1 hospice claim to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2011. We included in our sample all hospice enrollees who died between July 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011, so that we had complete data of their last 6 months of life. The study was exempt from full review by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University.

Measurement

Outcomes

Using revenue center code values of 0652,17 we first determined which hospice programs provided CHC based on the definition of having at least 1 patient covered by Medicare who were 66 or more years of age and received CHC in 2011. For patients who died between July and December, 2011 and were enrolled with hospices in which any patients used CHC in 2011, we created 3 binary variables to indicate if the patient received CHC, if the patient disenrolled from hospice, or if the patient was hospitalized after hospice disenrollment. Hospice disenrollment was defined as if: (1) they had only 1 hospice enrollment period and the last hospice date on the final hospice claim was not the date of death; or (2) if they had >1 hospice enrollment period. For patients with more than 1 hospice provider, we only included CHC data from the first hospice in which the decedent was enrolled to ensure that CHC use was prior to hospice disenrollment.

Independent variables

We included the characteristics of the hospice agency based on the Provider of Services (POS) file, including ownership type (for-profit and nonprofit), duration of hospice operation (years; <10, 10-18, 18-23, and >=24), size (measured as the number of individuals cared for during the study period by the hospice categorized at the quartiles of the distribution), and rural versus urban location. We also included use of general inpatient care (identified as revenue center code 0656) as an independent variable as use of CHC may be correlated with general inpatient care.

Patient demographics included age (categorized as 66-69 years, 70-74 years, 75-79 years, 80-84 years, and ≥85 years), gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, black, Hispanic, and other) and primary diagnosis based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes and categorized as follows: neoplasms; mental disorders; diseases of the nervous system and sense organs; diseases of the circulatory system; diseases of the respiratory system; symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions; and other. We also ascertained 8 chronic conditions using data from the Master Beneficiary Summary File, including heart disease (acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease), Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, kidney disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, depression, stroke, and cancer (breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, and endometrial). We then categorized decedents based on their count of comorbid conditions, and adjusted for time from hospice enrollment to death (a continuous variable from 0 day to 179 days).

In addition, we identified the county of residence and the hospital referral region (HRR) for each beneficiary using zip code information. We examined data pertaining to the county in which the patient resided using the Area Resource File (which included median county-level income and percentage of adults in the county with a high school education or less) and used HRRs to approximate markets. Prior literature generally used counties or HRRs to define the hospice market,18,19 but results are often insensitive to the choices between HRRs and counties.20 Another reason for using HHRs was to address the small sample size at the county level. We employed the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index21 as the HRR-level measure of hospice facility market competition (<0.15, 0.15-0.25, and ≥0.25, indicating competitive, moderately concentrated, and highly concentrated markets, respectively).

Statistical Analysis

We used x2 tests and t tests to examine the associations between CHC provision and hospice characteristics (hospice-level analyses), as well as the associations between CHC receipt and patient characteristics (patient-level analyses). Analyzing individual patient claims data, we used 3-level hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs) to identify patient-level, hospice-level, and HRR-level factors that were significantly associated with receipt of CHC. We calculated the variance inflation factor in a multivariable linear regression model22 and confirmed no multicollinearity issue among the independent variables.

To assess the associations between use of CHC and both hospice disenrollment and hospitalization, we fit two HGLMs, defining CHC receipt as the key independent variable. For both disenrollment and hospitalization, we also explored any significant interaction of CHC use with incomes or use of general inpatient hospice care. These two interactions were selected because prior literature had found that CHC effects on dying at home differed by patient’s household incomes,10 and inpatient hospice care may substitute for CHC use. We included an interaction term between CHC receipt and income in one model, and use of inpatient hospice care in the other model. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and a two-tailed p<.05 was used to define statistical significance. We also performed two sensitivity analyses, one that excluded hospices associated with a large for-profit chain and one that excluded hospice programs that had settled cases with the Department of Justice alleging false claims for care.

Results

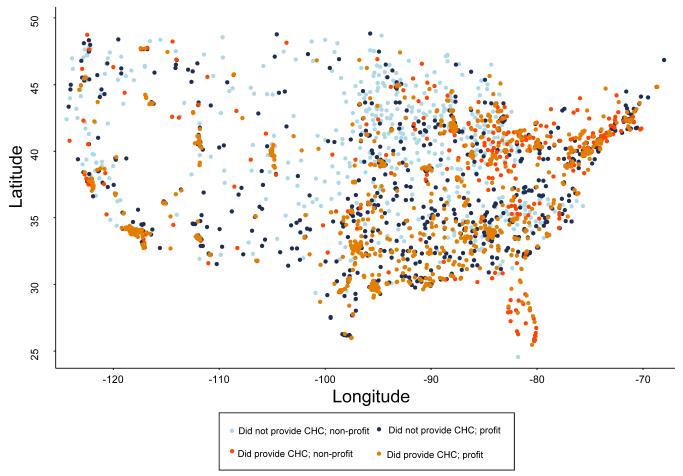

We found that at least 1 patient used CHC in only 42.7% (n=1,533) of hospices while no patients used CHC in the remaining hospices (n=2059). Hospices in which at least 1 patient used CHC were more likely to be for-profit, have a short duration of operation, have a larger volume, be located in urban areas, and provide general inpatient care as well (all P-values ≤ 0.001; Table 1). Among hospices which provided CHC, 1,217 provided general inpatient care and 316 did not. Figure 1 is a map of the US that shows the location of non-CHC and CHC hospices, by for-profit and nonprofit status in 2011. There seems to be more hospice programs providing CHC in the Northeast region and Florida.

Table 1.

Hospice characteristics according to provision of continuous home care

| Hospice characteristics | Having CHC claims N=1533 (42.7%) |

Not having CHC claims N=2059 (57.3%) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | <.001 | ||

| For-profit (no, %) | 1118 (48.8) | 1175 (51.2) | |

| Nonprofit (no, %) | 403 (31.6) | 874 (68.4) | |

| Duration (year, sd) | 11.5 (8.1) | 12.4 (8.1) | .001 |

| Volume (no. of patients in 2011, sd) | 371 (655) | 177 (256) | <.001 |

| Rurality | <.001 | ||

| Rural (no, %) | 266 (27.0) | 721 (73.0) | |

| Urban (no, %) | 1254 (48.6) | 1328 (51.4) | |

| General inpatient hospice care provision | <.001 | ||

| Yes (no, %) | 1217 (47.0) | 1372 (53.0) | |

| No (no, %) | 316 (31.5) | 687 (68.5) |

CHC: Continuous home care

Figure 1.

Map of hospice agencies in 2011, according to provision of continuous home care (CHC) and for-profit status

We also found that among hospices that had at least 1 patient who used CHC in 2011, a total of only 11.4% of all decedents used CHC during the study period. For patients who used CHC, the mean duration of CHC was 4.5 days (standard deviation: 5.3 days; median: 3 days; interquartile range: 2 to 5 days). Among the 1,246 hospice agencies that had more than 20 enrollees during the study period, the mean percentage of decedents who received CHC was 9.0% (standard deviation: 13.9%; median: 2.6%; maximum: 76.7%). Patient characteristics according to receipt of CHC are presented in Table 2. For patients who received CHC, only 12.4% received inpatient hospice care, whereas among patients who did not receive CHC, 30.5% received inpatient hospice care. Decedents who received inpatient hospice care (compared to those who did not receive inpatient hospice care) were less likely to receive CHC. Among 2,642 decedents who received both CHC and inpatient hospice care, 784 (29.7%) received CHC first, while 1,858 (70.3%) received general inpatient hospice care first. In multivariable analyses, decedents who were white, had more comorbidities, or enrolled in hospice due to cancer were more likely to use CHC compared with those who were non-white, had fewer comorbidities, or enrolled in hospice due to diseases other than cancer (Table 3). Decedents who were enrolled in hospice agencies that were for-profit, had a shorter duration of operation, or had a larger number of enrollees were more likely to use CHC.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics according to receipt of continuous home care

| Sample characteristics | Having CHC | Not having CHC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 21,274 (11.4) | 165,856 (88.6) | |

|

| |||

|

Demographic Factors

| |||

| Age | .053 | ||

| 66-69 | 1,385 (6.5) | 11,154 (6.7) | |

| 70-75 | 2,149 (10.1) | 16,798 (10.1) | |

| 75-79 | 2,814 (13.2) | 22,446 (13.5) | |

| 80-84 | 4,020 (18.9) | 32,185 (19.4) | |

| 85+ | 10,906 (51.3) | 83,273 (50.2) | |

| Sex | .110 | ||

| Male | 8,711 (41.1) | 68,863 (41.5) | |

| Female | 12,563 (59.1) | 96,992 (58.5) | |

| Race | <.001 | ||

| White | 18,168 (85.4) | 144,482 (87.1) | |

| Black | 1,305 (6.1) | 12,449 (7.5) | |

| Hispanic | 1,417 (6.7) | 5,901 (3.6) | |

| Other | 384 (1.8) | 3,024 (1.8) | |

|

| |||

|

Clinical Factors

| |||

| Number of comorbidities | <.001 | ||

| 0-2 | 2,227 (10.5) | 20,244 (12.2) | |

| 3 | 2,737 (12.9) | 23,460 (14.1) | |

| 4 | 4,009 (18.8) | 32,251 (19.5) | |

| 5 | 4,493 (21.1) | 34,542 (20.8) | |

| 6 | 3,865 (18.2) | 28,647 (17.3) | |

| 7-8 | 3,943 (18.5) | 26,712 (16.1) | |

| Primary diagnosis for hospice enrollment | <.001 | ||

| Neoplasms | 6,857 (32.2) | 49,874 (30.1) | |

| Mental disorders | 2,242 (10.5) | 17,817 (10.7) | |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 2,516 (11.8) | 13,270 (8.0) | |

| Diseases of the circulatory system |

3,790 (17.8) | 31,228 (18.8) | |

| Diseases of the respiratory system |

1,638 (7.7) | 14,529 (8.8) | |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill- defined conditions |

3,326 (15.6) | 28,610 (17.2) | |

| Other | 905 (4.3) | 10,528 (6.3) | |

| Receiving general inpatient hospice care | <.001 | ||

| No | 18,632 (87.6) | 115,274 (69.5) | |

| Yes | 2,642 (12.4) | 50,582 (30.5) | |

| Average days from hospice enrollment to death (sd) |

59.2 (65.5) | 48.1 (62.1) | <.001 |

|

| |||

|

Geographic Factors

| |||

| Metropolitan statistical area | <.001 | ||

| No | 764 (3.6) | 11,393 (6.9) | |

| Micropolitan | 1,343 (6.3) | 16,709 (10.1) | |

| Metropolitan | 19,167 (90.1) | 137,754 (83.1) | |

| Education (≥ High school; missing no=103) | <.001 | ||

| < 60% | 20 (0.1) | 143 (0.1) | |

| 60 - 70 | 161 (0.8) | 2,207 (1.3) | |

| 70 - 80 | 3,947 (18.6) | 22,580 (13.6) | |

| 80 - 90 | 13,950 (65.6) | 107,389 (64.8) | |

| ≥ 90 | 3,190 (15.0) | 33,440 (20.2) | |

| Median household income (missing no=103) | <.001 | ||

| < $33,000 | 81 (0.4) | 1,267 (0.8) | |

| $33,000 - $39,999 | 2,125 (10.0) | 28,300 (17.1) | |

| $40,000 - $49,999 | 10,187 (47.9) | 62,339 (37.6) | |

| $50,000 - $62,999 | 5,986 (28.1) | 48,418 (29.2) | |

| ≥ $63,000 | 2,889 (13.6) | 25,435 (15.3) | |

CHC: Continuous home care

Table 3.

Adjusted Associations between Patient Characteristics and Receiving Continuous Home Care

| Receiving CHC OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | |

| Age | |

| 66-69 | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) |

| 70-74 | 1.05 (0.99, 1.12) |

| 75-79 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.08) |

| 80-84 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.05) |

| 85+ | reference |

| Sex | |

| Male | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) |

| Female | reference |

| Race | |

| White | reference |

| Black | 0.70 (0.65, 0.75) |

| Hispanic | 0.90 (0.84, 0.98) |

| Other | 0.76 (0.67, 0.87) |

| Clinical Factors | |

| Number of comorbidities | |

| 0-2 | reference |

| 3 | 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) |

| 4 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.15) |

| 5 | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) |

| 6 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.15) |

| 7-8 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.16) |

| Primary diagnosis for hospice enrollment | |

| Neoplasms | reference |

| Mental disorders | 0.75 (0.70, 0.80) |

| Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs | 0.84 (0.79, 0.89) |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 0.75 (0.71, 0.79) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 0.68 (0.64, 0.73) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 0.77 (0.73, 0.82) |

| Other | 0.57 (0.52, 0.62) |

| Days from hospice enrollment to death (continuous variable) |

1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

| Geographic Factors | |

| Metro residence | |

| No | 0.98 (0.88, 1.10) |

| Micorpolitan | 0.84 (0.77, 0.92) |

| Metropolitan | reference |

| Median income of county | |

| Less than $33,000 | 0.83 (0.59, 1.18) |

| $33,000-40,000 | 0.86 (0.75, 0.99) |

| $40,000-50,000 | 0.91 (0.82, 1.02) |

| $50,000-63,000 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) |

| $63,000 or more | reference |

| Percent ≤ HS education of zip code | |

| Less than 60% | 1.05 (0.60, 1.82) |

| 60 to <70% | 0.86 (0.67, 1.12) |

| 70 to <80 % | 0.95 (0.85, 1.07) |

| 80 to <90% | 0.93 (0.86, 1.01) |

| 90% or more | reference |

| Hospice-level factors | |

| Hospice ownership | |

| Nonprofit | 0.53 (0.46, 0.61) |

| For-profit | reference |

| Year of hospice operation | |

| ≥24 | 0.54 (0.44, 0.65) |

| 19-24 | 0.55 (0.46, 0.65) |

| 10-19 | 0.60 (0.52, 0.69) |

| <10 | reference |

| Number of hospice admission during study period | |

| ≥1,247 | 3.78 (3.18, 4.50) |

| 545-1247 | 1.54 (1.31, 1.83) |

| 241-545 | 1.05 (0.91, 1.23) |

| <241 | reference |

| Market concentration | |

| Competitive market | 0.95 (0.78, 1.15) |

| Moderately concentrated market | 1.02 (0.81, 1.27) |

| Highly concentrated market | reference |

Compared with decedents who did not use CHC, patients who used CHC were less likely to disenroll from hospice (10.6% vs. 3.7%, p-value < 0.001). After adjusting for patient-, hospice-, and HRR-level variables, CHC recipients were less likely to have hospice disenrollment and less likely to be hospitalized (Table 4). Compared with decedents who did not receive CHC, decedents who received CHC had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.21 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.19 to 0.23) for hospice disenrollment, and an AOR of 0.37 (95% CI: 0.34 to 0.40) for hospitalization after hospice enrollment. We found a statistically significant interaction between CHC and general inpatient care use on hospice disenrollment/ hospitalization: among decedents who did not receive general inpatient hospice care, receiving CHC was strongly associated with hospice disenrollment (AOR 0.19; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.21) and hospitalization (AOR 0.32; 95% CI 0.29 to 0.35). Among decedents who received general inpatient hospice care, the associations were still statistically significant although more modest in magnitude (hospice disenrollment: AOR 0.35; 95% CI 0.29 to 0.42; and hospitalization: AOR 0.81; 95% CI 0.68 to 0.96). The interaction between CHC receipt and income was not statistically significant (P-value = 0.071 and 0.539 for hospice disenrollment and hospitalization, respectively). The results of sensitivity analyses were qualitatively similar to the main results.

Table 4.

Adjusted Associations between Receiving Continuous Home Care and Hospice Disenrollment/Hospitalization

| Hospice Disenrollment OR (95% CI) |

Hospitalization OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Receiving continuous hospice care | ||

| No | reference | reference |

| Yes | 0.21 (0.19, 0.23) | 0.37 (0.34, 0.40) |

| Demographic Factors | ||

| Age | ||

| 66-69 | 1.44 (1.35, 1.54) | 1.61 (1.48, 1.76) |

| 70-74 | 1.34 (1.26, 1.42) | 1.53 (1.42, 1.65) |

| 75-79 | 1.27 (1.21, 1.34) | 1.48 (1.39, 1.58) |

| 80-84 | 1.16 (1.11, 1.21) | 1.30 (1.23, 1.38) |

| 85+ | reference | reference |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.19 (1.15, 1.23) | 1.10 (1.06, 1.15) |

| Female | reference | reference |

| Race | ||

| White | reference | reference |

| Black | 1.46 (1.38, 1.55) | 1.95 (1.82, 2.08) |

| Hispanic | 1.32 (1.21, 1.44) | 1.38 (1.24, 1.54) |

| Other | 1.31 (1.17, 1.48) | 1.36 (1.17, 1.58) |

| Clinical Factors | ||

| Number of comorbidities | ||

| 0-2 | reference | reference |

| 3 | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 1.10 (1.00, 1.21) |

| 4 | 1.00 (0.93, 1.06) | 1.15 (1.05, 1.25) |

| 5 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 1.28 (1.17, 1.39) |

| 6 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.03) | 1.42 (1.30, 1.55) |

| 7-8 | 0.98 (0.91, 1.05) | 1.56 (1.43, 1.70) |

| Primary diagnosis for hospice enrollment | ||

| Neoplasms | reference | reference |

| Mental disorders | 0.69 (0.64, 0.73) | 0.65 (0.60, 0.70) |

| Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs | 0.65 (0.61, 0.69) | 0.60 (0.55, 0.66) |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.18) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) | 1.21 (1.13, 1.31) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 0.84 (0.79, 0.88) | 0.84 (0.79, 0.90) |

| Other | 0.90 (0.83, 0.98) | 0.75 (0.67, 0.85) |

| Receiving general inpatient hospice care | ||

| No | reference | reference |

| Yes | 0.65 (0.62, 0.68) | 0.78 (0.74, 0.83) |

| Days from hospice enrollment to death (continuous variable) |

1.01 (1.01, 1.01) | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) |

| Geographic Factors | ||

| Metro residence | ||

| No | 1.00 (0.93, 1.09) | 1.05 (0.95, 1.16) |

| Micorpolitan | 0.91 (0.85, 0.98) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) |

| Metropolitan | reference | reference |

| Median income of county | ||

| Less than $33,000 | 1.15 (0.92, 1.43) | 0.97 (0.74, 1.26) |

| $33,000-40,000 | 1.02 (0.92, 1.13) | 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) |

| $40,000-50,000 | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.12) |

| $50,000-63,000 | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | 1.03 (0.93, 1.13) |

| $63,000 or more | reference | reference |

| Percent ≤ HS education of zip code | ||

| Less than 60% | 1.36 (0.8, 2.34) | 1.51 (0.81, 2.82) |

| 60 to <70% | 1.16 (0.97, 1.39) | 1.41 (1.15, 1.74) |

| 70 to <80 % | 1.12 (1.02, 1.23) | 1.17 (1.04, 1.32) |

| 80 to <90% | 1.08 (1.01, 1.15) | 1.09 (1.01, 1.19) |

| 90% or more | reference | reference |

| Hospice-level factors | ||

| Hospice ownership | ||

| Nonprofit | 0.86 (0.80, 0.91) | 0.84 (0.77, 0.91) |

| For-profit | reference | reference |

| Year of hospice operation | ||

| ≥24 | 0.90 (0.82, 0.98) | 0.77 (0.69, 0.86) |

| 19-24 | 0.93 (0.85, 1.01) | 0.77 (0.70, 0.86) |

| 10-19 | 0.89 (0.83, 0.95) | 0.85 (0.78, 0.92) |

| <10 | reference | reference |

| Number of hospice admission during study period | ||

| ≥1,247 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.02) | 0.95 (0.85, 1.06) |

| 545-1247 | 0.87 (0.80, 0.93) | 0.85 (0.77, 0.93) |

| 241-545 | 0.84 (0.79, 0.90) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.93) |

| <241 | reference | reference |

| Market concentration | ||

| Competitive market | 1.12 (1.03, 1.23) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.20) |

| Moderately concentrated market | 0.94 (0.84, 1.05) | 1.03 (0.90, 1.17) |

| Highly concentrated market | reference | reference |

Discussion

Our research showed that, among Medicare beneficiaries, approximately 43% of national hospices provided CHC, and among decedents enrolled in CHC provision hospice, only 11.4% received CHC level of care. After adjusting for other patient and hospice characteristics, we found that decedents who received CHC were less likely to experience hospice disenrollment and hospitalization after hospice enrollment. Our results indicate that CHC services provide patients and their families with comprehensive hospice home care while also decreasing the likelihood of hospice disenrollment or hospitalization once enrolled, which has the potential to substantially decrease Medicare spending. This effect was apparent among patients who used inpatient hospice care as well as among those who did not.

Our findings build upon previous work in important ways. Although our results are consistent with prior literature, which has indicated that CHC services are beneficial to hospice enrollees, we conducted the first study we know of exploring the link between CHC use and decreased hospice disenrollment and transitions in care after hospice enrollment. Given the high costs related to fragmented end-of-life care, use of CHC services may both improve the quality and reduce the costs of end-of-life care. Given the benefits of CHC services, it is surprising that less than half of hospices cared for patients who used CHC services. Our study was not designed to identify barriers to CHC use; however, previous research has suggested that maintaining qualified nursing staff for CHC services is challenging.23 Nursing staff providing CHC services are responsible for medication adjustments and symptom management in times of patient deterioration or crisis,24 and are required to work a minimum of eight hours. CHC services cannot be provided by contract nurses and at least half of the hours per shift must be staffed by a registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, or licensed vocational nurse,4 which may be difficult for some hospices to ensure and sustain.

Second, we found hospice enrollees who received CHC were less likely to receive inpatient hospice care while those who received inpatient hospice care were less likely to receive CHC; these findings indicate that CHC and inpatient hospice care may be substitute options for one another. Additionally, both CHC and inpatient hospice care were associated with a decrease in the likelihood of hospice disenrollment and hospitalization after hospice enrollment. Our results support the benefits of using these two intensive and expensive levels of hospice care, which are intended to manage symptoms for terminally ill patients. Although the comparisons between CHC and general inpatient hospice care are not our primary goal, we found the effects of CHC on decreasing hospice disenrollment and hospitalization after hospice enrollment were larger than those of inpatient hospice care. Given that 72% of hospice programs provided general inpatient hospice care but only 43% of hospice programs provided CHC, encouraging all hospice programs to provide CHC may further improve hospice care quality.

We also determined that several patient and hospice characteristics were associated with CHC use. Hospice users who were white, had cancer, had more comorbidities, or were cared for by a for-profit hospice agency were more likely to use CHC. Furthermore, there is substantial variation in the proportion of decedents within hospices that received CHC: in most hospice programs, very few enrollees used CHC whereas in some hospice programs, more than two-thirds of their enrollees used CHC. Future research to understand why such patterns exist and whether added use of CHC among patients currently less likely to use CHC might provide cost and quality benefits is warranted.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, as an observational study, we could not establish causal inferences. However, the patterns of CHC provision and the associations between CHC and transition in care, are informative. Second, there was a lack of data on patient preferences and we hence could not assess if the use of CHC services reflected patient and families’ desires or resulted from differences in provider practices and organizational routines. For instance, whether or not to choose CHC during a crisis depends much on patient preferences, which have great impact on the decision to elect hospice disenrollment or hospitalization. Understanding how CHC use may be associated with patient and family satisfaction with care is also a topic for future investigation. Third, prior literature found that the relationships between CHC and transitions in care differed, depending on patient’s income levels.10 Our study, however, did not find a statistically significant interaction between income and CHC use on hospice disenrollment and hospitalization. Plausible explanations for the discrepancies could be due to different outcomes or different populations used in each of the studies. Lastly, we were unable to quantify costs associated with use of CHC services, which would be helpful to determine if such intensive hospice services, although costly, may offset more expensive hospitalization costs. Our findings suggest that additional study of the cost-effectiveness of CHC services is necessary.

In conclusion, less than 50% of hospice programs provided CHC, with a small minority of patients within these hospices using CHC services. Furthermore, our research supports the conclusion that CHC provision is associated with a decreased likelihood of hospice disenrollment and hospitalization after hospice enrollment. Although the Medicare Hospice Benefit covers CHC services, the limited use of CHC and considerable variation in use nationally raises the concern that CHC may be underutilized. Understanding patient preferences about receiving CHC and providing services accordingly not only will benefit patients and their families, but may also mitigate high hospitalization costs at the end of life for these terminally ill individuals.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This study was supported by grant 1R01CA116398-01A2 from the National Cancer Institute (Drs. Aldridge and Bradley); the John D. Thompson Foundation (Dr. Bradley); grant 1R01NR013499-01A1 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (Dr. Aldridge); and grant 1K01HS023900-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Dr. Wang).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures: None of the other coauthors have conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues. Institute of Medicine . Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC): Mar 19, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [Accessed on September 21, 2015];Medicare benefit policy manual. 2011 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c09.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [Accessed on April 30, 2015];Update to Hospice Payment Rates, Hospice Cap, Hospice Wage Index, Quality Reporting Program, and the Hospice Pricer for Fiscal Year 2014. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM8876.pdf.

- 4.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [Assessed on Oct 16, 2015];Managing continuous home care for symptom management. Tips for providers. Available at http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/regulatory/CHC_Tip_sheet.pdf.

- 5.Federal Register [Assessed on Oct 16, 2015];Rules and Regulations. 2009 Aug 6;74(No. 150) Available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2009-08-06/pdf/E9-18553.pdf#page=30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith MA, Seplaki C, Biagtan M, DuPreez A, Cleary J. Characterizing hospice services in the United States. Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):25–31. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plotzke M, Christian TJ, Pozniak A, et al. [Accessed April 21, 2015];Medicare hospice payment reform: analyses to support payment reform. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Hospice/Downloads/May-2014-AnalysesToSupportPaymentReform.pdf.

- 8.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [Assessed on November 16, 2015];NHPCO’s Facts and Figures. 2015 Edition. Available at http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2015_Facts_Figures.pdf.

- 9.Miller SC, Kinzbrunner B, Pettit P, Williams JR. How does the timing of hospice referral influence hospice care in the last days of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(6):798–806. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barclay JS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA, Johnson KS. Association of hospice patients' income and care level with place of death. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):450–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casarett D, Harrold J, Harris PS, et al. Does Continuous Hospice Care Help Patients Remain at Home? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(3):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldridge MD, Canavan M, Cherlin E, Bradley EH. Has Hospice Use Changed? 2000-2010 Utilization Patterns. Med Care. 2015;53(1):95–101. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aldridge MD, Schlesinger M, Barry CL, et al. National hospice survey results: for-profit status, community engagement, and service. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):500–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson MD, Herrin J, Du Q, et al. Impact of hospice disenrollment on health care use and medicare expenditures for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(28):4371–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, et al. Geographic Variation of Hospice Use Patterns at the End of Life. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(9):771–80. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, et al. End-of-Life Transitions among Hospice Enrollees. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jgs.13939. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hospice Medicare Billing Codes Sheet - CGS Administrators [Assessed January 1, 2015]; Available at http://www.cgsmedicare.com/hhh/education/materials/pdf/hospice_medicare_billing_codes_sheet.pdf.

- 18.Iwashyna TJ, Chang VW, Zhang JX, Christakis NA. The lack of effect of market structure on hospice use. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1531–51. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.10562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wennberg JE, Copper MM, editors. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. American Hospital Publishing; Chicago: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaughlin CG, Normolle DP, Wolfe RA, McMahon LF, Jr., Griffith JR. Small-area variation in hospital discharge rates. Do socioeconomic variables matter? Med Care. 1989;27(5):507–21. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zwanziger J, Melnick GA, Mann JM. Measures of hospital market structure: a review of the alternatives and a proposed approach. Socioecon Plann Sci. 1990;24(2):81–95. doi: 10.1016/0038-0121(90)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freund RJ, Littell RC. SAS System for Regression, 1986 Edition. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leff EW, Cohen CE, Wright BJ. Avoiding the pitfalls of hospice continuous care. Home Healthc Nurse. 2001;19(1):31–6. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200101000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman A, Thompson J, Chandler EM. Continuous care: a home hospice benefit. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(1):19–20. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.19-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]