Takamura et al. show that most lung CD8+ TRM cells are not maintained in the inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) but are maintained in specific niches created at the site of tissue regeneration, which are termed as repair-associated memory depots (RAMDs).

Abstract

CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM cells) reside permanently in nonlymphoid tissues and provide a first line of protection against invading pathogens. However, the precise localization of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung, which physiologically consists of a markedly scant interstitium compared with other mucosa, remains unclear. In this study, we show that lung CD8+ TRM cells localize predominantly in specific niches created at the site of regeneration after tissue injury, whereas peripheral tissue-circulating CD8+ effector memory T cells (TEM cells) are widely but sparsely distributed in unaffected areas. Although CD69 inhibited sphingosine 1–phosphate receptor 1–mediated egress of CD8+ T cells immediately after their recruitment into lung tissues, such inhibition was not required for the retention of cells in the TRM niches. Furthermore, despite rigid segregation of TEM cells from the TRM niche, prime-pull strategy with cognate antigen enabled the conversion from TEM cells to TRM cells by creating de novo TRM niches. Such damage site–specific localization of CD8+ TRM cells may be important for efficient protection against secondary infections by respiratory pathogens.

Introduction

Nonlymphoid tissues (NLTs) that have experienced infections are subsequently surveyed by at least two subpopulations of memory T cells: tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM cells) and effector memory T cells (TEM cells). TRM cells are now recognized as a majority of memory T cells in the NLTs (Steinert et al., 2015), spending their lifetimes within the NLTs without recirculation (Gebhardt et al., 2009; Masopust et al., 2010; Wakim et al., 2010; Hofmann and Pircher, 2011; Teijaro et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2012) and conferring rapid and robust protective immunity upon secondary pathogen invasion (Gebhardt et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2012; Mackay et al., 2012; Shin and Iwasaki, 2012). Most CD8+ TRM cells patrol epithelial layers, a frontline of the mucosa (Gebhardt et al., 2011; Ariotti et al., 2012), where they serve as both initiators/enhancers of local immune responses in an antigen (Ag)-specific manner and as cytotoxic cells (Schenkel et al., 2013, 2014a; Ariotti et al., 2014). In contrast, most CD4+ TRM cells are present below the basement membrane (e.g., dermis) and generally form clusters, consistent with their functional role as helper cells (Gebhardt et al., 2011; Iijima and Iwasaki, 2014; Turner et al., 2014). In the case of skin, intestine, and vagina, several developmental cues for differentiation into TRM cells have been reported, such as local activation and cytokine signals for the up-regulation of CD69 and down-regulation of sphingosine 1–phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1; Masopust et al., 2010; Skon et al., 2013; Bergsbaken and Bevan, 2015; Mackay et al., 2015a), TGF-β signals for up-regulation of another key TRM cell marker, CD103, and down-regulation of T-box transcription factors (Zhang and Bevan, 2013; Mackay et al., 2015b) and IL-15 to promote survival (Mackay et al., 2013, 2015b). A recent study has also revealed that, after acquisition of these local tissue-specific signals, cells committed to become TRM cells up-regulate Hobit and Blimp-1 that serve as transcriptional programing of tissue residency (Mackay et al., 2016). Thus, the entry of effector cells into the epithelial tissues is an initial and pivotal checkpoint in the development of TRM cells. Based on this, experimentally induced recruitment of cells into the epithelial tissues by Ag-independent local inflammation or topical chemokine administration has been shown to be sufficient for the establishment of TRM cells, a method known as a prime-pull strategy (Mackay et al., 2012; Shin and Iwasaki, 2012). In contrast to TRM cells, TEM cells are defined as nonresident memory T cells present in the NLTs that circulate between NLTs and the blood stream (Schenkel and Masopust, 2014).

It is thought that CD8+ TRM cells in the lung are distinct from TRM cells in other peripheral sites in terms of their maintenance. After the resolution of respiratory virus infections, large numbers of Ag-specific memory CD8+ T cells persist in both the airways and the lung parenchyma (LP; Hogan et al., 2001a; Wiley et al., 2001), and both populations can mediate substantial control of a secondary virus infection in the lungs (Hogan et al., 2001b; Ely et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2014; McMaster et al., 2015). Memory CD8+ T cells in the airways that can be recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage show no evidence of recirculation, categorizing them as TRM cells (Ely et al., 2006). Because of the harsh airway environment, however, T cells in the airways have been shown to have a half-life of only 10–14 d (Ely et al., 2006). Based on this, it has been proposed that the number of memory CD8+ T cells in the airways is maintained by continual recruitment from the systemic memory pool under steady-state conditions, rather than by prolonged survival or cytokine-driven homeostatic proliferation within the airway tissue (Ely et al., 2006). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that residual Ag remained in the lung-draining mediastinal LN (MLN) for several months after an acute respiratory infection (Jelley-Gibbs et al., 2005, 2007; Zammit et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2010; Takamura et al., 2010), suggesting a model in which recent reactivation of memory CD8+ T cells by long-lived depots of viral Ag in the MLN is required for continual recruitment of memory CD8+ T cells to the airways (Zammit et al., 2006). This model was based on the observation that memory CD8+ T cells in the MLN and the lung showed a similar activation phenotype as determined by CD69. However, this model seemingly conflicted with a later study showing that CD69 must be down-regulated for egress of lymphocytes from the LNs (Shiow et al., 2006). Additionally, a large proportion of memory CD8+ T cells isolated from the LP have been shown to be contaminants from the lung vasculature (LV; Anderson et al., 2012, 2014). Thus, our understanding of memory CD8+ T cells in the LP has to be revised by using intravascular (i.v.) staining to distinguish cell population in the LV from those in the actual LP.

Here, we have comprehensively analyzed lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells using parabiosis and i.v. staining and definitively show that CD8+ TRM cells in the lung are not maintained through the continual recruitment of new cells. Instead, we identify for the first time the presence of specific niches for the maintenance of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung. These niches are found primarily in the lung interstitium (LI) with partial extension to the LP (to precisely describe our histological observations, we refer to the previously adopted term LP as LI/LP hereafter). These TRM niches are distinct from conventional inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) but are associated with tissue remodeling after injury. Based on our observations, we refer to the CD8+ TRM niches as repair-associated memory depots (RAMDs). We further demonstrate differential roles of CD69 in generation and maintenance of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung and an indispensability of a cognate Ag for successful establishment of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung by a prime-pull strategy.

Results

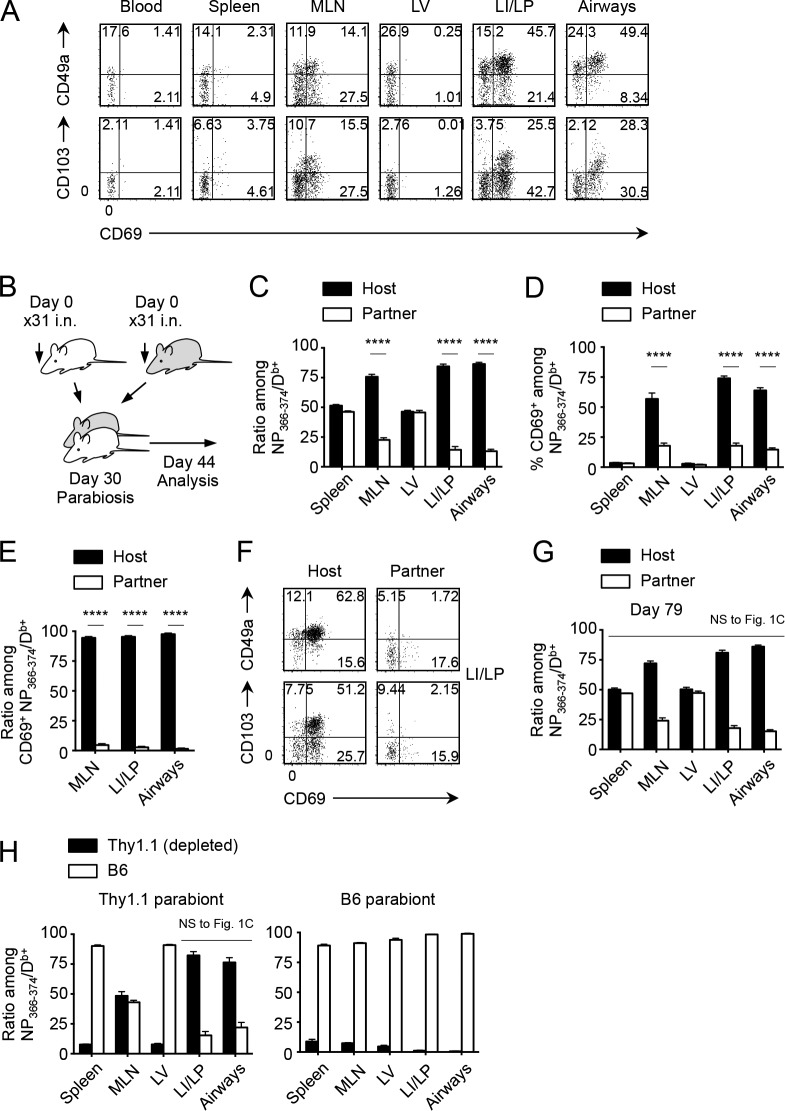

Memory CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways are not maintained by continual recruitment from the circulation

i.n. infection with influenza virus A/HK-x31 (x31) induces populations of nucleoprotein (NP)-specific memory CD8+ T cells in the lung that exhibit typical TRM phenotypes (CD69+CD49a+CD103+; Fig. 1 A). By using i.v. staining (Anderson et al., 2012) coupled with parabiosis that provides a continual supply of cells from the congenically marked partner through shared circulation, we first reevaluated the previously established concept that memory CD8+ T cells in the lung are continuously replenished by cells recruited from the circulation (Fig. 1 B). Complete equilibration of host- and partner-derived Ag-specific memory CD8+ T cells in the spleen and LV was observed 2 wk after the surgery. However, partner cells comprised only ∼20% in the MLN, LI/LP, and airways (Fig. 1 C), indicating reduced recruitment or retention of partner cells in the presence of host TRM cells in these tissues. A critical difference between host and partner cells in these tissues was the expression of CD69, as unlike host cells, most of the partner-derived, virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells in the MLN, LI/LP, and airways were not reactivated, presumably despite the presence of residual Ag (Fig. 1 D). Almost all NP-specific CD69+ cells in MLN, LI/LP, and airways were host derived (Fig. 1 E), suggesting the role of reactivation in the retention of host memory CD8+ T cells (Schenkel et al., 2014b; Mackay et al., 2015a). Furthermore, although host memory CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP were markedly skewed toward TRM phenotypes, most partner cells lacked expression of CD49a and CD103 (Fig. 1 F). Collectively, the data suggest that memory CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways consist of two distinct populations: a major (∼80%) population of TRM cells that expresses a highly activated phenotype and a minor (∼20%) population of peripheral tissue-circulating TEM cells which have not been recently reactivated by Ag.

Figure 1.

Continual recruitment-independent maintenance of lung-resident CD8+ T cells. (A) Expression of CD49a, CD103, and CD69 on NP366–374/Db+ CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 30 after i.n. infection with x31. (B) Congenic mice were infected i.n. with x31 and were subjected to parabiotic surgery 30 d later. Mice were analyzed on day 14 after the surgery unless otherwise specified. (C) Host/partner ratios of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue. (D) Ratios of CD69+ cells among host and partner NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue. (E) Host/partner ratios of CD69+ NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue. (F) Expression of the indicated molecules on host and partner NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP. (G) Host/partner ratios of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 79 after the surgery. (H) Host/partner ratios of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue of x31-immune mice depleted of Thy1.1+ cells 1 d before parabiosis. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and SEM of four to five pairs of mice). ****, P < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s posthoc tests (C and D), two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Sidak’s posthoc tests (E), and Student’s t test in comparison with each counterpart in Fig. 1 C (G and H).

We considered the possibility that continual recruitment from the circulation would take longer than the 2-wk time frame used in the prior parabiosis experiments. However, we detected no significant increase in the ratio of partner cells in the MLN, LI/LP, and airways even after 7 wk of parabiosis (compare Fig. 1, C and G). These data contradict previous assumptions about the recruitment of memory and suggest that neither LI/LP nor airway-resident memory CD8+ T cells are maintained through continual recruitment from systemic circulation. We confirmed this conclusion by joining x31-immune pairs, of which circulating, but not resident, memory CD8+ T cells of one parabiont were depleted with CD90.1 (Thy1.1)-specific antibody just before surgery. 2 wk after surgery, most of the memory CD8+ T cells in the circulation (spleen and LV) of Thy1.1 parabionts were replaced by C57BL/6 (B6)-derived cells (Fig. 1 H). However, loss of circulating Thy1.1 cells had no impact on the ratio of those in the LI/LP and airways of Thy1.1 hosts (compare Fig. 1, C and H, left). These results clearly demonstrate that maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells in the lung tissues does not require recruitment of new cells from the circulation.

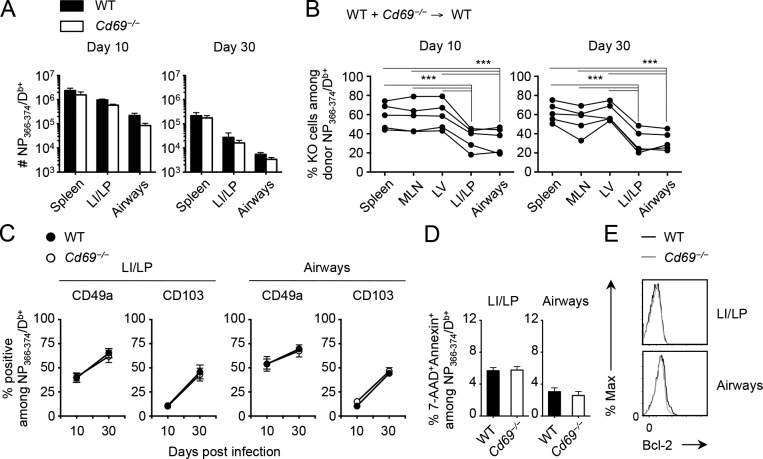

Reduced accumulation of Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells in the lung

The long term retention of CD8+ TRM cells in the lungs suggests that CD49a and CD103 play a key role in this process because the adhesive functions of these molecules has been well established (Ray et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2011). In contrast, the potential role of CD69 in the maintenance of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung is unclear (Turner et al., 2014). To address this issue, we investigated whether Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells can be maintained in the lung after x31 infection. When WT and Cd69−/− mice were infected with x31, comparable levels of CD8+ T cell expansion and memory formation were observed in the spleen of both mice, with only a modest decrease in the number of Ag-specific effector as well as memory CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways in the Cd69−/− mice (Fig. 2 A). However, when the tissue distributions of WT and Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells were compared in mixed BM chimeric mice, where the relative migration and retention of cells from the two donors can be directly compared, the ratio of virus-specific Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways relative to WT counterparts was greatly reduced (Fig. 2 B). This was true during both the acute and late phases of infection, suggesting that Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells are less competitive in accumulating in these tissues. Nevertheless, the absence of CD69 had little if any influence on the expression of other potential adhesion molecules, such as CD49a and CD103, on virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways (Fig. 2 C). Moreover, relative reduction in the proportion of Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways of BM chimeras was unlikely to be caused by poor survival of these cells, as comparable expression of the prosurvival protein Bcl-2, annexin V binding, and 7-AAD incorporation at the peak of infection were observed on both WT and Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2, D and E). These results suggest that CD69 itself may directly influence the accumulation of CD8+ T cells in the lung during the early phase of infection.

Figure 2.

Reduced accumulation of Cd69−/−/CD8+ T cells in the lung compared with CD69+/CD8+ T cells. (A) Numbers of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue of WT or Cd69−/− mice at day 10 and 30 after i.n. infection with x31. (B–E) Mice were treated with busulfan and 24 h later were injected with a 1:1 mixture of WT and Cd69−/− BM cells. 6 wk later, these mice were infected i.n. with x31. (B) Ratios of Cd69−/− cells among donor NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 10 and 30 PI. Lines connect data from each individual recipient mouse. (C) Ratios of CD49a+ and CD103+ cells among NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at the indicated time points. (D) Ratios of 7-AAD+annexin V+ cells among NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 30 PI. (E) Representative histograms showing Bcl-2 expression in WT (black lines) and Cd69−/− (gray lines) NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 30 PI. Data are representative of two independent experiments (mean and SEM of three to five mice per group). ***, P < 0.001 by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Sidak’s posthoc tests (A and C), one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc tests (B), and Student’s t test (D).

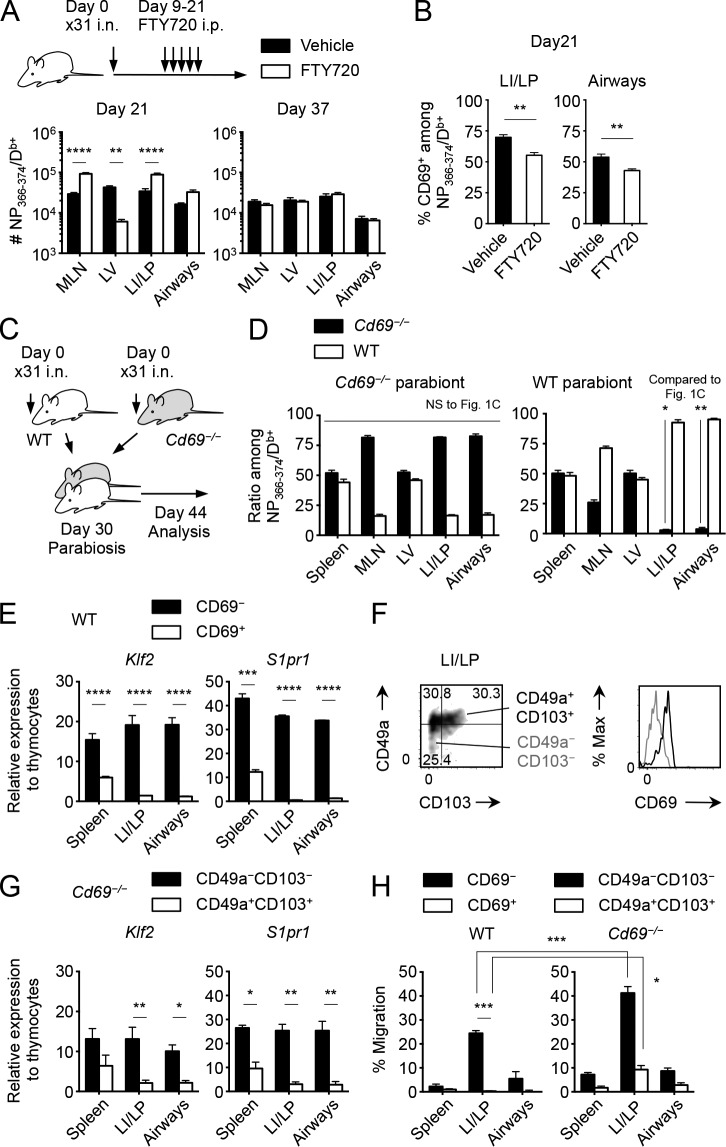

CD69-independent maintenance of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung

It has been previously established that S1P1 promotes the egress of effector CD8+ T cells from inflamed peripheral tissues (Skon et al., 2013; Mackay et al., 2015a) and that its activity is inhibited by CD69 (Shiow et al., 2006). Therefore, we speculated that the relative inefficiency in accumulation of Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells in the lung (Fig. 2 B) reflected increased egress from the tissues. To address this issue, we investigated whether FTY720, an agonist of S1P1, would replicate the data with Cd69−/− mice. Repeated injection of FTY720 for 12 d from the peak of infection resulted in a significant increase in the number of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways (Fig. 3 A, day 21). This was despite the fact that FTY720 also blocked extravasation of cells from the LNs, presumably a source of new effector CD8+ T cells during the early phase of infection (Fig. 3 A, see day 21, MLN and LV). These data confirmed that S1P1 plays a role in the egress of CD8+ T cells from the LI/LP. Importantly, the percentage of CD69+ cells among NP-specific CD8+ T cells decreased in the lung during the FTY720 treatment (Fig. 3 B), indicating that CD69− cells, which committed to exit from the tissues, might mainly account for the increase of cells in the lung. In fact, when FTY720 treatment was discontinued, differences in the numbers of memory CD8+ T cells in the lung were no longer observed between treated and untreated groups (Fig. 3 A, day 37). Thus, the fact that Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells are less competitive than WT cells in accumulating in the lung (Fig. 2 B) indicates that the expression of CD69 enhances the retention of CD8+ T cells in the lung at least during the early phase of infection.

Figure 3.

Differential roles of CD69 in the retention of circulatory and resident memory CD8+ T cells in the lung. (A and B) Mice were infected i.n. with x31 and were treated for 13 consecutive days with FTY720 or the vehicle alone from day 9. (A) Numbers of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at the indicated time points. (B) Ratios of CD69+ cells among NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 21 PI. (C and D) WT and Cd69−/− mice were infected i.n. with x31 and were parabiotically joined 30 d later. Mice were analyzed at day 14 after the surgery. (D) WT/Cd69−/− ratios among NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue of Cd69−/− (left) and WT (right) parabionts. (E) Expression of the indicated genes in sorted CD69+ or CD69− CD44hiCD8+ T cells in each tissue of WT mice at day 30 PI. (F) Expressions of CD49a and CD103 by NP-specific CD8+ T cells and those of CD69 by the indicated populations in the LI/LP of WT mice. (G) Expression of the indicated genes in sorted CD49a+CD103+ or CD49a−CD103− CD44hiCD8+ T cells in each tissue of Cd69−/− mice at day 30 PI. (H) S1P-specific chemotaxis of activated and nonactivated NP-specific CD8+ T cells isolated from each tissue of WT or Cd69−/− mice at day 30 PI. Data are representative of two independent experiments (mean and SEM of three to six mice per group or three pairs of mice for parabiosis). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Sidak’s posthoc tests (A, E, and G), Student’s t test in comparison with each counterpart in the Fig. 1 C (D), and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s posthoc tests (H).

Next, we investigated whether the expression of CD69 is also essential for the maintenance of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung. If this is the case, parabiosis of x31-immune Cd69−/− and WT mice should result in a decrease in the ratio of Cd69−/− CD8+ TRM cells in the lungs of the Cd69−/− parabionts (Fig. 3 C). Surprisingly, ∼80% of Cd69−/− CD8+ TRM cells still remained in the LI/LP and airways of Cd69−/− hosts at 2 wk after surgery (Fig. 3 D, left), comparable with the host cell percentages observed in WT pairs (Fig. 1 C). These results definitely demonstrate that CD8+ TRM cells can be maintained in the LI/LP and airways independently of CD69. However, a lack of CD69 led to significant loss of CD8+ TEM cells in the lung of the WT partner (compare Fig. 1 C, unshaded bars and Fig. 3 D, shaded bars, right). Collectively, the data strongly support a model in which S1P1-mediated egress and CD69-induced retention of CD8+ T cells within the lung play a key role in at least two stages: retention of effector CD8+ T cells during the early stages of infection and retention of CD8+ TEM cells during the steady-state memory phase. However, once established, CD69 is no longer required for the retention of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung.

Because both transcriptional down-regulation of S1P1 as well as the protein-level down-regulation through CD69-induced complex formation influence the egress of memory CD8+ T cells from the NLTs (Skon et al., 2013), we next tested the possibility that S1P1 expression was transcriptionally down-regulated in CD8+ TRM cells in the lung. At day 30 postinfection (PI), Klf2 and its downstream target S1pr1 were highly expressed in nonactivated (CD69−: mostly circulatory TEM cells) cells in the lung, suggesting that transmigration of CD8+ T cells into the lung itself had little impact on the expression of these mRNAs (Fig. 3 E). In contrast, expressions of the Klf2 and S1pr1 were significantly down-regulated in reactivated (CD69+: mostly resident type) memory CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3 E). We obtained identical results using Cd69−/− memory CD8+ T cells, where reactivated and nonactivated cells were distinguished by their expression of CD49a and CD103 instead of CD69 (Fig. 3, F and G). These results suggest that CD69 may not be required for inhibiting the S1P1-mediated egress of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung. Yet, in the case of T cell egress from the thymus and LN, CD69-mediated inhibition of S1P1 theoretically preceded transcriptional down-regulation of S1pr1 (Grigorova et al., 2010; Cyster and Schwab, 2012; Preston et al., 2013), explaining the nonredundant role of CD69 in T cell retention early after activation. Thus, we further examined whether reactivated Cd69−/− CD8+ TRM cells in the lung still possess residual responsiveness to its ligand, S1P. As indicated by their reduced S1pr1 mRNA expression, reactivated WT memory CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP showed no S1P-specific chemotactic activities, whereas their nonactivated counterparts, especially cells in the LI/LP, retained strong reactivity to S1P (Fig. 3 H, left). Importantly, genetic deletion of CD69 further enhanced S1P-specific chemotaxis of nonactivated (CD49a−CD103−) CD8+ TEM cells in the LI/LP (Fig. 3 H, right). Despite their low expression levels of S1pr1, reactivated (CD49a+CD103+) Cd69−/− memory CD8+ T cells still retained their migratory responses to S1P (Fig. 3 H, right). Identical results were observed when activated and nonactivated CD8+ T cells of WT mice were separated by the expression of CD49a and CD103, the same method used for Cd69−/− mice (not depicted). These findings reinforced the concept that, in the absence of CD69, circulatory memory CD8+ T cells cannot stay in the LI/LP because of strong S1P-specific chemotaxis (Fig. 3 D, right) and provided conclusive evidence that Cd69−/− CD8+ TRM cells in the LI/LP can be maintained even though these cells possess residual reactivity to S1P (Fig. 3, D, left, and H).

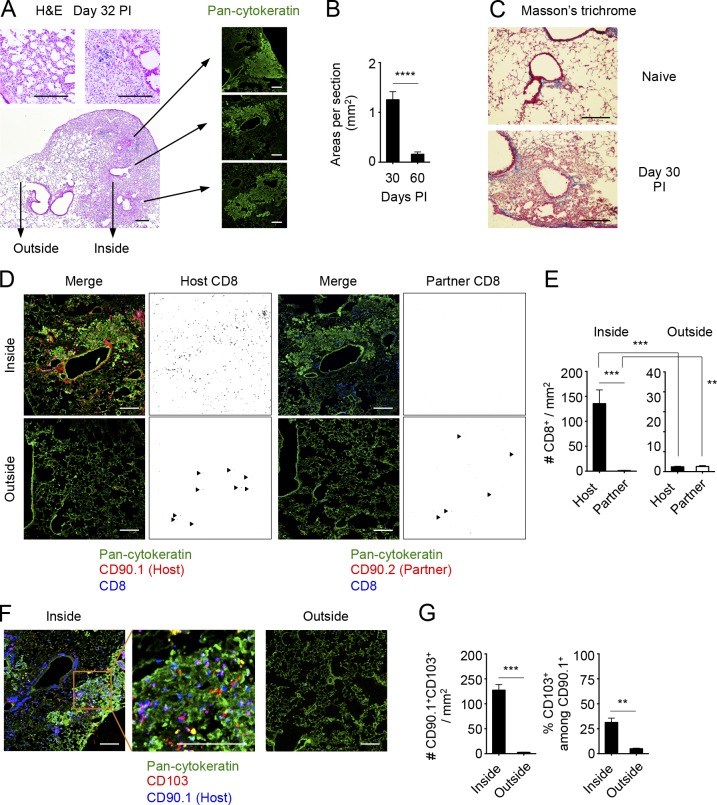

Distinct distributions of resident and circulatory memory CD8+ T cells in the lung

The stable retention of Cd69−/− CD8+ TRM cells in the lung, despite their enhanced migratory potential, may be caused by limited exposure to the S1P gradient. Thus, we compared the distributions of TRM and TEM cells in the lungs in congenically distinct, x31-immune mice that were joined by parabiosis. This allowed us to distinguish TRM and TEM cells by using host- and partner-congenic markers, respectively (Fig. 1 F). After the resolution of infection, partially confluent foci of peribronchiolar cellular infiltrates with rather diffuse thickening of alveolar walls in surrounding areas were observed until at least 60 d PI (Fig. 4, A and B). Such peribronchiolar foci of lymphocytic infiltrates uniformly surrounded aggregates of cytokeratin-expressing basal cells, which were consistent with Krt pods generated in the process of bronchoalveolar regeneration after viral injuries (Fig. 4 A; Kumar et al., 2011; Vaughan et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2015). These peribronchiolar foci gradually shrank over time with minimum signs of residual fibrosis (Fig. 2, B and C). Host CD8+ T cells were detected predominantly in association with these regenerative foci, both within and around the Krt pods (Fig. 4, D and E). Many of the host T cells in such regions were also CD103+, suggesting that they were TRM cells (Fig. 4, F and G). Consistent with previous studies (Iijima and Iwasaki, 2014; Turner et al., 2014), host CD4+ T cells were mainly found as clusters (Fig. 5 A, arrowheads). In most cases, host CD4+ T cell clusters surrounded B cell follicles, forming highly organized structures indicative of iBALT (Fig. 5 B). Although iBALT-like structures could be found in association with the dense lymphocytic infiltrates and some host CD8+ T cells also formed small clusters (Fig. 5 A, arrows), a greater part of peribronchiolar foci consisted of sequestered host CD8+ T cells that were distributed secluded from the iBALT structures (Fig. 5, A and B). Importantly, although potential lymphangiogenesis that accompanied tissue regeneration was observed within the peribronchiolar foci, CD8+ TRM cells were clearly segregated from such lymphatic-rich regions (Fig. 5 C). In fact, a majority of host CD8+ T cells in the peribronchiolar foci distributed distant to lymph vessels as compared with those in the iBALT and unaffected LI (Fig. 5 D and Fig. S1). This spatial separation of TRM cells from the lymphatics may explain the CD69-independent retention of cells despite residual reactivity to S1P (Fig. 3 H). In sharp contrast, donor-derived tissue-circulating CD8+ TEM cells were rarely found in such peribronchiolar foci but were detected in the interstitium of thin-walled terminal/respiratory bronchioles and alveoli (Fig. 4 D), indicating distinct spatial distributions between CD8+ TRM and TEM cells in the lung. Note that although cells in the LV could also be detected in similar locations to CD8+ TEM cells (Fig. S2; Anderson et al., 2012), a combination of parabiosis and i.v. staining enabled precise distinction between these cell populations (Fig. 5 E). Collectively, the data demonstrated a strict anatomical compartmentalization between resident and tissue/blood-circulating memory CD8+ T cells in the lung and apparent segregation of lung CD8+ TRM cells into their specific niches, which are distinct from iBALT but are associated with the foci of tissue regeneration. Based on such unique features, we refer to the CD8+ TRM niches in the lung as RAMDs.

Figure 4.

CD8+ TRM cells resided within the peribronchiolar foci in the LI/LP. (A–G) Congenic mice were infected i.n. with x31 and were subjected to parabiotic surgery 18–22 d later. Mice were analyzed at day 14 after the surgery (day 32–36 PI). (A) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained images of peribronchiolar foci (left) and pan-cytokeratin–expressing cell aggregates in the indicated section of the peribronchiolar foci (right). (B) Mean areas of peribronchiolar foci per sections. (C) Representative peribronchiolar foci in the lung stained with Masson’s trichrome at day 30 PI. (D) Distributions of host (CD90.1+) and partner (CD90.2+) CD8+ T cells inside or outside of peribronchiolar foci. Pan-cytokeratin, green; CD90.1 or CD90.2, red; CD8, blue. Binary images of CD90.1+CD8+ or CD90.2+CD8+ cells were generated by using ImageJ software (right). Similar distributions of host and partner cells were also observed in the CD90.2+ parabionts. Line-shaped lymph vessels stained by anti-CD90 isoform antibodies were excluded (Kretschmer et al., 2013). Arrowheads indicate host (left) or partner (right) CD8+ T cells in the unaffected area. (E) Numbers of host and partner CD8+ T cells inside or outside of peribronchiolar foci. (F) Distributions of CD103+ host-derived T cells (Thy1+) inside or outside of peribronchiolar foci. Pan-cytokeratin, green; CD103, red; CD90.1, blue. (G) Numbers of CD103+CD90.1+ cells, and ratios of CD103+ cells among CD90.1+ cells inside or outside of peribronchiolar foci. Data are representative of two independent experiments (mean and SEM of six slides from at least four to five mice per group). (B, E, and G) **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 by Student’s t test. Bars, 200 µm.

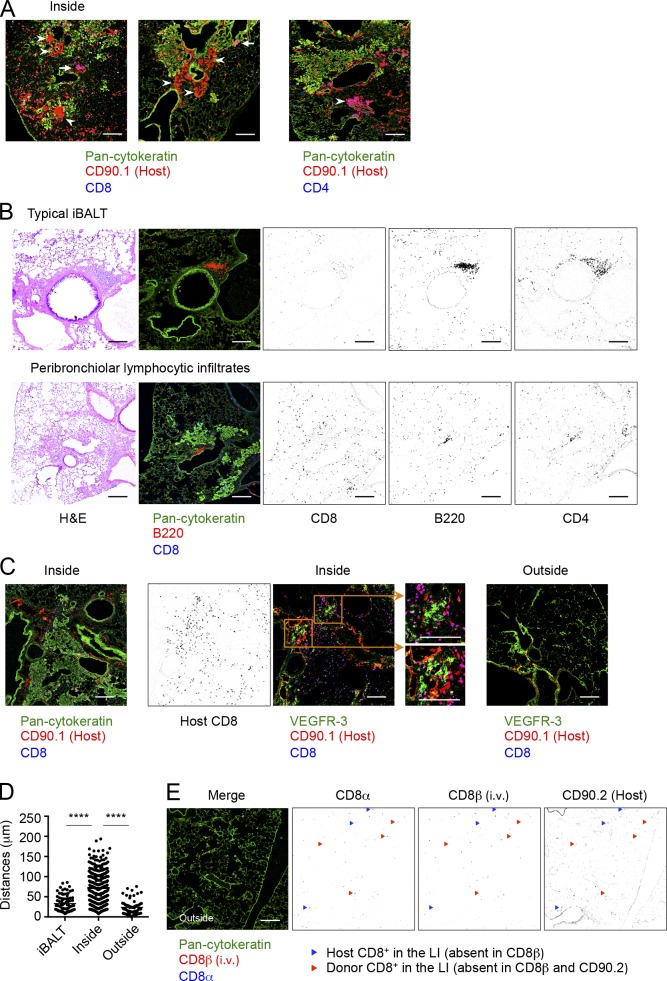

Figure 5.

Features of CD8+ TRM niches in the LI/LP. (A, C, and D) Congenic mice were infected i.n. with x31 and were subjected to parabiotic surgery 18–22 d later. Mice were analyzed at day 14 after the surgery (day 32–36 PI). (A) Representative CD8+ (arrowheads) and CD4+ (arrows) T cell clusters found in the peribronchiolar foci. Pan-cytokeratin, green; CD90.1, red; CD8 or CD4, blue. (B) Mice were infected i.n. with x31. Representative H&E-stained (left) and fluorescent (middle) micrographs of iBALT (top) and peribronchiolar foci (bottom) in the lung at day 30 PI. Pan-cytokeratin, green; B220, red; CD8, blue. (Right) Binary images of CD8+, CD4+, or B220+ cells were generated by using ImageJ software. Anti-CD4 antibody was stained using serial sections. (C) Representative fluorescence micrographs showing distributions of host (CD90.1+)-derived CD8+ T cells and lymph vessels (VEGFR-3+) inside (left and middle, serial sections) or outside (right) of peribronchiolar foci. (Left) Pan-cytokeratin, green; CD90.1, red; CD8, blue. (Middle and right) VEGFR-3, green; CD90.1, red; CD8, blue. Binary images of CD8+ cells were generated from the right micrographs. (D) Distances of host CD90.1+CD8+ cells from a closest VEGFR-3+ cell in the peribronchiolar foci. (E) Mice were injected i.v. with anti-CD8β antibody 3 min before tissue harvest. Shown are distributions of host (CD90.2+) and partner CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP. Pan-cytokeratin, green; CD8β (i.v.), red; CD8α, blue. Blue triangles indicate host cells in the LI/LP; CD8α+CD8β (i.v.)−CD90.2+. Red triangles indicate donor cells in the LI/LP; CD8α+CD8β (i.v.)−CD90.2−. Data are representative of two independent experiments (mean of six slides from at least four to five mice per group). ****, P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc tests. Bars, 200 µm.

CD8+ T cells recruited into the lung at the early stage of infection can differentiate to TRM cells

We next investigated the kinetics by which the CD8+ TRM population is established in the lung after infection. Pairs of mice infected at the same time were joined at various time points (Fig. 6 A), and the establishment of TRM cells by partner cells (determined by equilibration of host and partner cells in the LI/LP and airways) was monitored at day 32 PI. Note that full chimerism was attained in the systemic circulation by day 10–14 after surgery (not depicted). Interestingly, successful establishment of partner CD8+ TRM cells in the lung TRM niche was observed when parabiosis was performed earlier, but not later, than day 6 PI (Fig. 6 B). Some pairs joined at day 2 PI showed relatively increased ratios of partner cells in the LI/LP and airways (Fig. 6 B). Acquisition of the TRM phenotypes was also evident in partner cells in those pairs (compare Fig. 1 F and Fig. 6 C). These results suggest that cells recruited to the lung around the peak of CD8 T cell response (day 10–11 PI) may be involved in the lung TRM niche, although a wide variation in donor cell ratios was observed depending on whether systemic equilibrium had been achieved by the time of harvest. As expected, only some of the parabiotic pairs joined at day 2 PI showed successful equilibrium in the spleen at day 11, and recruitment of partner cells to the lung was observed only in the pairs with significant splenic equilibrium (Fig. 6 D). Collectively, the data provided a critical turning point between resident and circulatory memory CD8+ T cells in the lung: distribution into the lung before the peak of cellular responses in this organ, which also parallels the peak of tissue damage necessary for creating the RAMDs, is essential for subsequent formation of CD8+ TRM cells.

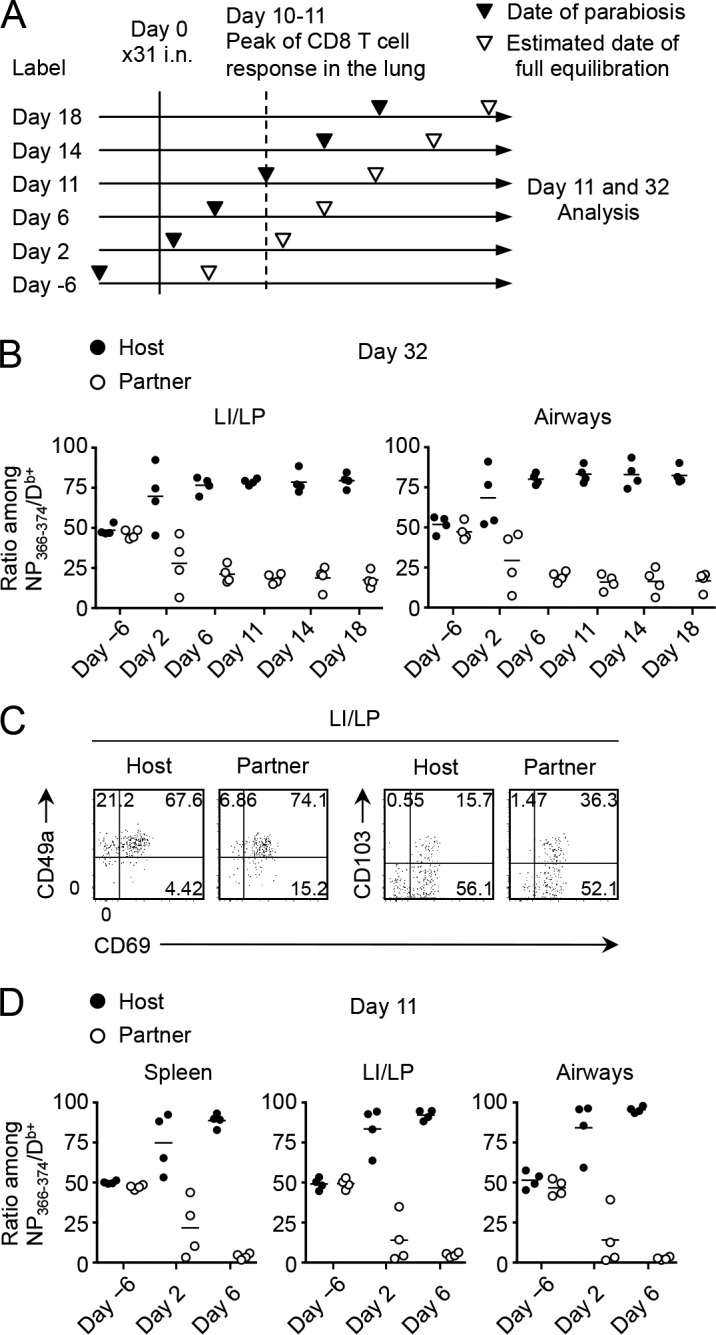

Figure 6.

CD8+ T cells recruited to the lung at an early phase of infection gave rise to TRM cells. (A) Pairs of mice infected with x31 at the same time underwent the parabiotic surgery at various time points. Some pairs were joined before infection. Full equilibration of the host and partner CD8+ T cells in the blood was achieved ∼11–14 d after the surgery. (B) Host/partner ratios of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 32 PI. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (C) Expression of the indicated molecules on host and partner NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP. (D) Host/partner ratios of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 11 PI. Data are representative of two independent experiments (two pairs of mice).

Local administration of cognate Ag is required for the establishment of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung

Given that acute recruitment of CD8+ T cells to the NLTs (e.g., skin and vagina) induced by Ag-independent inflammation or topical chemokine application enables local establishment of CD8+ TRM cells (Mackay et al., 2012; Shin and Iwasaki, 2012), we investigated whether such a prime-pull strategy could also be applied to the lung. i.p. injection of a high-dose influenza virus led to the generation of substantial numbers of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells in the circulation accompanied by limited recruitment of them into the LI/LP and airways owing to the lack of productive pulmonary infection (Fig. 7 A; Zammit et al., 2006; Takamura et al., 2010). Low expressions of CD69, CD49a, and CD103 on i.p. primed memory CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways revealed these to be CD8+ TEM cells (Fig. 7 B). Using this model, we injected i.n. a toll-like receptor ligand, CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN), to induce Ag-independent inflammation in the lung. At the peak of CpG ODN–induced inflammation in the lung, we observed considerably enhanced recruitment of i.p. primed, NP-specific effector CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways (Fig. 7 C, day 11, gray bars). However, such increments in the numbers were no longer observed in the LI/LP and airways after the lung inflammation had resolved (Fig. 7 C, day 30, gray bars), indicating that, unlike other mucosal tissues, effector CD8+ T cells recruited to the lung by Ag-independent inflammation were unable to form TRM cells. Interestingly, simultaneous administration of CpG ODN and cognate Ag led to massive acute recruitment of i.p. primed effector CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways followed by significant retention of memory T cells even at a later time point (Fig. 7 C, unshaded bars). i.p. primed memory CD8+ T cells that remained in the lung had acquired typical TRM phenotypes, which were not observed in cells after CpG ODN injection alone (Fig. 7 D). We further tested whether such a strategy could be applied even after memory CD8+ T cells were fully differentiated. As shown in Fig. 7 (E and F), circulatory-to-resident conversion of memory CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways was evident by local administration of CpG ODN plus cognate Ag but not by CpG ODN alone. Hence, not only inflammation-mediated recruitment, but also a cognate Ag is required for the formation of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung. Notably, a single-shot administration of CpG ODN plus NP366–374 peptide alone without prior i.p. infection was unable to generate detectable levels of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung, indicating that CD8+ TRM cells detected in the lung were derived from cells elicited by i.p. infection with x31 (Fig. 7 G). We further considered the possibility that i.n. administration of NP peptide may lead to the expansion of i.p. primed, NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the MLN with a resultant increase in the numbers of cells in the circulation that can continue to seed the lung tissue. However, we did not see statistically significant increase in the numbers of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in both the MLN and the spleen even after i.n. administration with NP peptide (Fig. 7, C and E). In addition, analysis using Fucci transgenic (Tg) mice that can visualize real-time cell cycle progression by tracking two cell cycle–specific proteins, Cdt1 and Geminin (Sakaue-Sawano et al., 2008; Tomura et al., 2013), revealed that only small fractions of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the MLN were in proliferative cycles after NP peptide administration (Fig. 7 H). These results indicate that CD8+ T cell encounter with the cognate Ag in the lung, but not in the MLN, is a key event for their conversion from circulatory to resident forms in the lung. Because of the critical relationship between local tissue damage and the formation of lung TRM niches, we further speculated that local administration of an Ag in the presence of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells in the circulation causes certain tissue damage, the repairing of which subsequently creates the RAMDs that enables TRM cell conversion. As expected, the peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltrates surrounding Krt pods were observed exclusively in i.p. infected mice that received CpG ODN plus cognate Ag (Fig. 8, A and B). These results strongly support our findings that the recruitment of cells earlier than the peak of tissue damage is essential for the establishment of CD8+ TRM cells (Fig. 6). We further tested whether bystander memory CD8+ T cells with a distinct specificity to the administered peptide could be involved in the TRM cell pool in the lung through the damage repair process. We thus examined the numbers of acidic polymerase (PA)–specific CD8+ T cells in the settings of x31-prime (i.p.), NP peptide–pull (i.n.) strategy, the same method used in the experiments shown in Fig. 7 C. Although the addition of NP peptide had no impact on the CpG ODN–induced acute recruitment of PA-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways (Fig. 8 C, day 11), we observed a significant retention, albeit at a lower level, of PA-specific memory CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP, but not in airways, in mice injected i.n. with CpG ODN plus NP peptide (Fig. 8 C, day 30, unshaded bar), in which the RAMDs were created (Fig. 8 A). However, relative efficiency of TEM to TRM cell conversion (calculated by the ratio of Ag-specific CD8+ cells in the tissues per those in the spleen) exerted by NP-specific CD8+ T cells (Ag specific) was much higher than that by PA-specific (bystander) CD8+ T cells (Fig. 8 D; also see Figs. 7 C and 8 C), suggesting that the sole recruitment of cells to the RAMDs may not be sufficient for the formation of TRM cells. Importantly, PA-specific memory CD8+ T cells detected in the LI/LP did not show TRM phenotypes (Fig. 8 E), indicating that the acquisition of TRM phenotypes in the LI/LP depends on the local presence of relevant Ag. Collectively, these data suggest that although some bystander memory CD8+ T cells recruited to the LI/LP can be involved in the RAMDs, local Ag may be required for the optimal establishment of CD8+ TRM cells in the LI/LP, acquisition of TRM phenotypes, and subsequent recruitment of memory CD8+ T cells to the airways.

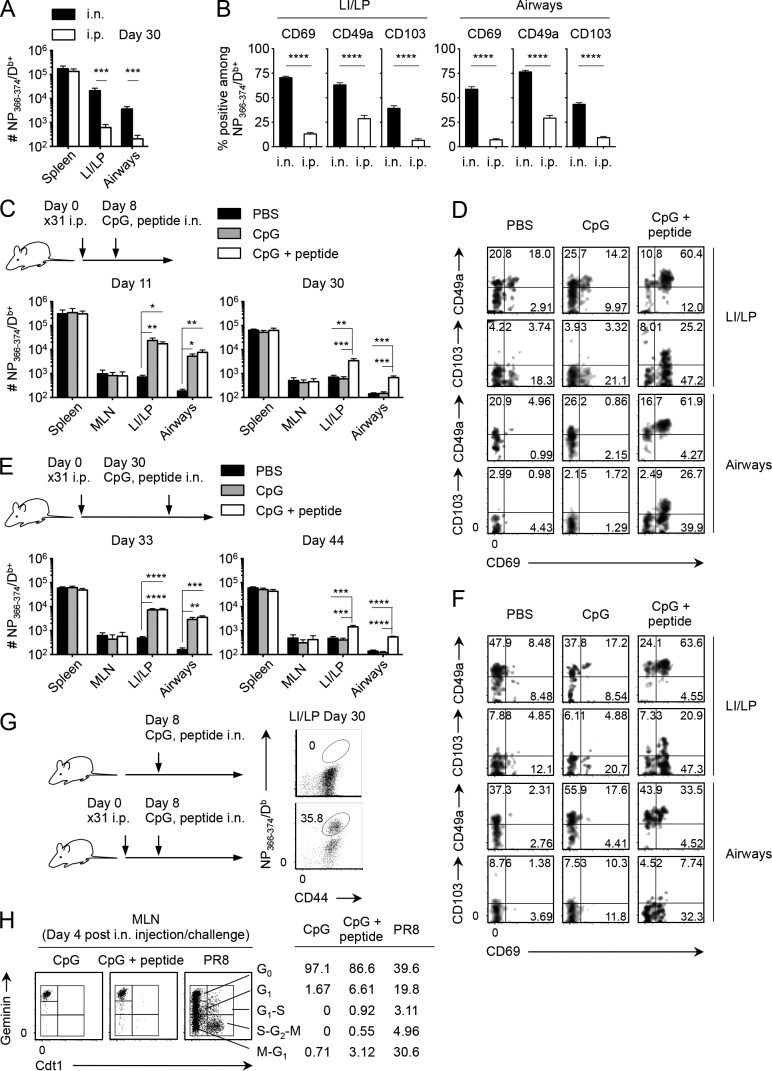

Figure 7.

Prime-pull vaccination with a cognate Ag converted TEM cells to TRM cells in the lung. (A–H) Mice were infected i.n. (A) or i.p. (A–E, G, and H) with x31. Some i.p. infected mice were then injected i.n. with PBS, CpG ODN, or CpG ODN + NP366–374 peptide at the indicated time points. (A) Numbers of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 30 PI. (B) Ratios of CD69+, CD49a+, and CD103+ cells among NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways. (C) Numbers of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 11 and 30 PI (day 3 and 22 after injection). (D) Expression of indicated molecules on NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways of mice shown in C at day 30 PI. (E) Numbers of NP-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 33 and 44 PI (day 3 and 14 after injection). (F) Expression of indicated molecules on NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP and airways of mice shown in G at day 44 PI. (G) Uninfected mice and mice infected i.p. with x31 were injected i.n. with CpG ODN + NP366–374 peptide 8 d later as shown in C. Representative dot plots showing the binding of NP366–374/Db tetramers on CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP mice at day 30 PI (day 22 after injection). (H) Fucci Tg mice were infected i.p. with x31 and then injected i.n. with CpG ODN or CpG ODN + NP366–374 peptide at day 8 PI. A group of x31-infected mice was challenged i.n. with PR8 at day 30 PI as a positive control to show the proliferating cells in the MLN. Expression of the Cdt1 and Geminin in NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the MLN of Fucci Tg mice at day 4 after treatment is shown. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells in each gate. Data are representative of two independent experiments (mean and SEM of five to six mice per group). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 by Student’s t test (A and B) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc tests (C and E).

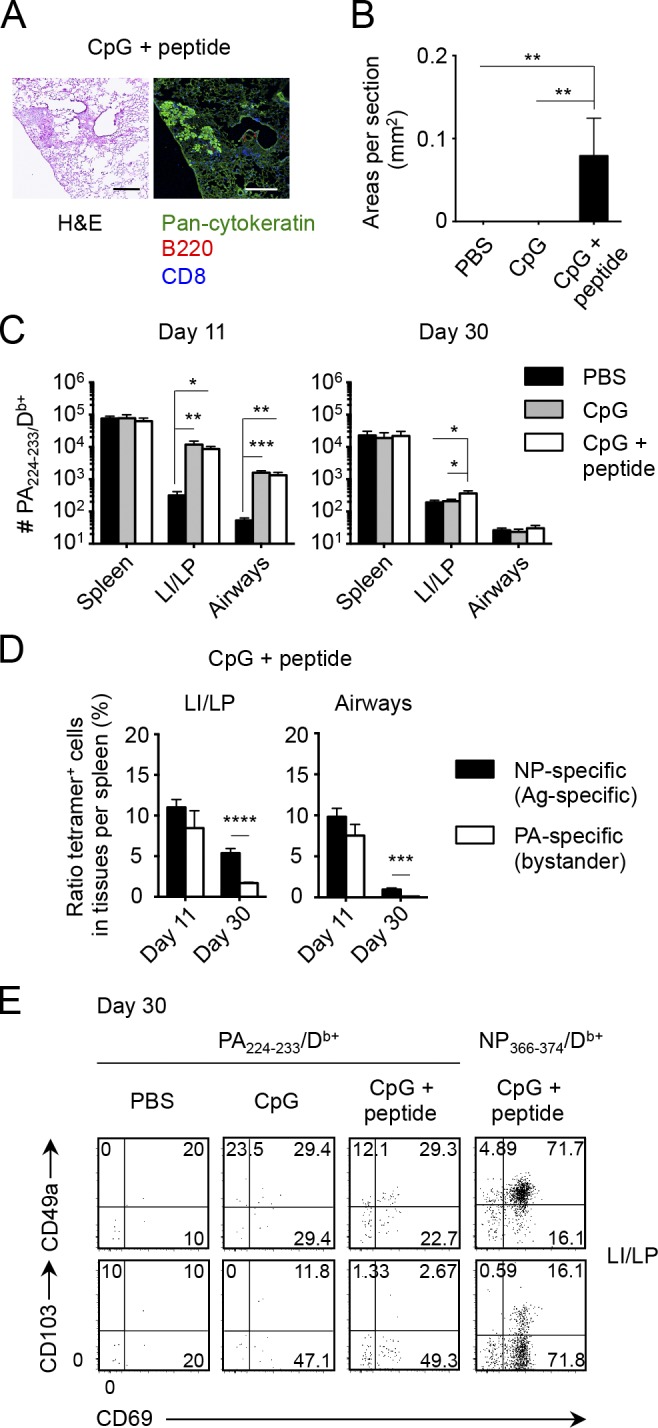

Figure 8.

Local Ag plays a role in the formation of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung. (A–E) Mice infected i.p. with x31 were then injected i.n. with PBS, CpG ODN, or CpG ODN + NP366–374 peptide at day 8 as shown in Fig. 7 C. (A) Representative H&E-stained (left) and fluorescent (right) micrographs of peribronchiolar foci in mice treated i.n. with CpG ODN + NP366–374 peptide at day 30 PI. Pan-cytokeratin, green; B220, red; CD8, blue. Similar infiltrates were not observed in mice treated i.n. with PBS or CpG alone. Bars, 200 µm. (B) Mean areas of peribronchiolar foci in the lung were measured in mice shown in A at day 30 PI. (C) Numbers of PA-specific CD8+ T cells in each tissue at day 11 and 30 PI (day 3 and 22 after treatment). (D) Ratio of tetramer+ cells in tissues relative to those in the spleen ([# tetramer+ cells in a tissue/# tetramer+ cells in the spleen] × 100) of mice treated i.n. with CpG ODN + NP366–374 peptide. (E) Representative dot plots showing the expression of indicated molecules on PA- and NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the LI/LP of mice treated with either PBS, CpG ODN, or CpG ODN + NP366–374 peptide. Data are representative of two independent experiments (mean and SEM of five to six mice per group). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc tests (B and C) and Student’s t test (D).

Discussion

In contrast to the skin, intestine, and vagina, the lung comprises a relatively ill-defined interstitium, which seems unsuitable for the long-term maintenance of TRM cells. In this study, we show that lung-resident CD8+ T cells localized within the auxiliary developed specific niches as RAMDs. The RAMDs consist of peribronchiolar foci surrounding Krt pods, which are known to be created after regeneration of damaged tissue, and are distinct from conventional iBALT structures. Memory CD8+ T cells in the thin interstitium, however, are circulating TEM cells that retain the expression of S1pr1 and are driven to exit in response to S1P. The TRM niches are occupied with TRM precursors by the peak of CD8+ T cell responses in the lung and are no longer available for cells recruited later, such as TEM cells. During this early period, WT CD8+ T cells have an advantage over Cd69−/− counterparts in reaching the TRM niche because of their ability to inhibit S1P1-mediated tissue egress by CD69. Even though this process is relatively effective, it is not essential, as a majority of Cd69−/− CD8+ T cells can still give rise to TRM cells when WT competitors are absent. Owing to the restricted availability of the CD8+ TRM niche and its developmental relationship with the damage regeneration process, simple prime-pull strategy is unable to establish CD8+ TRM cells in the lung. Instead, i.n. administration with trace amounts of cognate Ag in the presence of preformed circulating Ag-specific CD8+ T cells enables the creation of de novo TRM niches, followed by the conversion from TEM to TRM cells.

Morphological changes of the bronchiolar/alveolar walls and the appearance of Krt pods in association with the peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltrations are major hallmarks of the RAMD. In response to severe damage of the bronchiolar as well as alveolar epithelia, distal airway stem cells that express keratin 5 are activated, undergo rapid proliferation, and assemble at the damaged site (observed as Krt pods), where these cells differentiate and reconstruct the damaged lung tissues (Kumar et al., 2011; Vaughan et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2015). Because complete tissue recovery from such severe damage takes a couple of months (Narasaraju et al., 2010), it makes sense that CD8+ TRM cells that are rapid responders to reinfections are committed to intensively defend such weak spots during this period. In contrast, CD4+ TRM cells and memory B cells, cell populations that need to interact with each other for recall responses, are maintained mainly in the organized iBALT structures. Such CD8+ TRM cell–specific niches regionally created at the site of injury are also observed in the skin (Gebhardt et al., 2011; Zaid et al., 2014). We suggest that the previously reported gradual decline in the numbers of CD8+ TRM cells in the lung for the first couple of months PI could be accompanied by the wane in areas and numbers of RAMDs as tissue regeneration proceeds and that, after full reconstruction, some of the RAMDs may remain for an additional period like iBALT, but most of them will disappear. Such a transitional appearance of RAMDs may account for the relatively shorter longevity of CD8+ TRM cell–mediated local protection in the lung as compared with those in other mucosa (Wu et al., 2014).

In the case of iBALT, a sequence of developmental cues is known to be involved in the formation and maintenance of this lymphoid structure: T cell–derived IL-17 as an initiator followed by chemokines CXCL13 and CCL19 for the accumulation of T cells and B cells and lymphocyte- as well as DC-derived lymphotoxin for long-term maintenance (GeurtsvanKessel et al., 2009; Halle et al., 2009; Rangel-Moreno et al., 2011). Because the RAMDs in the lung have no apparent B cell follicles and resemble extended T cell areas of secondary lymphoid tissues, most of these factors, especially CXCL13 and CCL19, would not be required for their formation. Instead, it is conceivable that cells constituting such auxiliary developed regenerative tissues could be a source of unique factors necessary for differentiation and maintenance of TRM cells, such as TGF-β (Hu et al., 2015), CD4+ T cell–mediated indirect signals (Laidlaw et al., 2014), and cognate Ag (Khan et al., 2016). Because persistent depots of viral Ag were specifically observed in the peribronchiolar foci (Kim et al., 2010), Ag-presenting cells in the RAMDs may provide TCR-mediated tonic signals necessary for the acquisition of TRM phenotypes (Turner et al., 2014) and also for up-regulation of an antiviral molecule, IFITM3 (Wakim et al., 2013). Moreover, at an early phase of infection, these Ag-presenting cells may play a role in the selection of memory-precursor effector CD8+ T cells possessing high-affinity T cell receptors (Frost et al., 2015). However, reactivation-induced up-regulation of CD69, the subsequent transcriptional down-regulation of Klf2 and S1pr1, and segregation from lymph-rich areas in the RAMDs seem apparently redundant from the perspective of inhibiting S1P1-mediated egress. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the activated phenotypes exhibited by CD8+ TRM cells play an additional role other than simply promoting tissue retention. At present, the histological nature of putative CD8+ TRM niches in the airways remains unclear. Considering the known short life span of airway CD8+ TRM cells (Ely et al., 2006), along with our current parabiosis data, we assume that CD8+ TRM niches in the airways exist within the bronchiolar walls adjacent to those in the LI/LP and that the numbers of CD8+ TRM cells in the airways are likely maintained by the continual recruitment of cells from the LI/LP but not from the circulation. Hence, residual Ag-driven reactivation of CD8+ TRM cells in the LI/LP could be a driving force for the continual recruitment to the airways in close vicinity to the areas of tissue damage. Such possibilities will need to be addressed in future studies.

Materials and methods

Mice, virus, infections, and treatments

Influenza viruses x31 and A/PR8/34 (PR8) were grown, stored, and titered as previously described (Jelley-Gibbs et al., 2005). B6 mice were purchased from CLEA Japan, Inc. B6.PL-Thy1a/CyJ (CD90.1+) and B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ mice (CD45.1+) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Cd69−/− mice (B6 background; Murata et al., 2003) were provided by Toshinori Nakayama. Fucci Tg mice (B6 background; Sakaue-Sawano et al., 2008) were provided by M. Tomura. Mice (6–8 wk) were infected i.n. (300 EID50) or i.p. (104 EID50) with x31. Some groups of mice were injected i.p. with 150 µg FTY720 (Cayman), i.n. with 1 µg CpG ODN (InvivoGen), or i.n. with 20 µg of flu NP366–374 peptide. All animal studies were approved by Kindai University.

Tissue harvest and flow cytometry

Mice were injected i.v. with 1 µg anti-CD8β 3 min before tissue harvest. Cells in the lung airways were recovered by lavage with 5 × 1 ml PBS, followed by plastic adherence for 1 h at 37°C. Lung tissues were digested by collagenase D (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C and enriched by centrifugation in 40/80% Percoll gradient. MLN and spleen cells were obtained by straining through nylon mesh and enriching by either plastic adherence (MLN) or panning on anti–mouse IgG–coated flasks, followed by RBC lysis in buffered ammonium chloride. Cells were blocked first with mAbs to FcRγIII/II and then stained with allophycocyanin-conjugated influenza NP366–374/Db or PA224–233/Db tetramer. Tetramer-labeled cells were washed and stained with fluorescence-conjugated reagents purchased from BD (CD45.1 and CD90.1), BioLegend (CD8α, CD8β, CD69, CD103, Bcl-2, and annexin V), TONBO Bioscience (CD90.2), or Beckman Coulter (7-AAD). Tetramers were generated by the Trudeau Institute Molecular Biology Core. Samples were run on LSRFortessa flow cytometers (BD), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Mixed BM chimera

Recipient mice were injected i.p. with 600 µg of busulfan (Otsuka Pharmaceutical). The next day, BM cells isolated from Cd69−/− and WT mice were mixed 1:1, and a total of 2–2.5 × 107 cells were injected i.v. Chimeras were rested for 6 wk for reconstitution and were bled to confirm the presence of the donor CD8+ T cells before virus infection.

Parabiosis

Mice were anesthetized, and flank hair was removed with a clipper. A longitudinal skin incision was made from the knee to the elbow on a single lateral side along with a 1-cm lateral peritoneal incision. Two mice were joined together by suturing each reciprocal peritoneal opening. Two mattress stiches were made on the lateral edges of the skin section to hold the mice in the upright position, and the dorsal and ventral sides of the skin section of each mouse were further joined with wound clips. Blood was obtained from mice at 10 d after the surgery to confirm equilibration. In some experiments, Thy1.1 mice were injected i.p. with 250 µg anti-CD90.1 antibody (19E12) 1 d before surgery.

Chemotaxis assay

Migration of CD8+ T cells of x31-infected mice was analyzed in Transwell chambers with 5-µm pore–size polycarbonate filters (Corning). 106 cells were added to the upper chamber. An optimal concentration of 10−8 M S1P (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared in the serum-free medium (Hybridoma-SFM Complete DPM; Gibco) and added to the lower chamber. After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 4 h, the number of cells in the upper and lower chambers was analyzed by flow cytometry. Percent migration was calculated as (# cells in the lower chamber)/[(# cells in the upper chamber) + (# cells in the lower chamber)] × 100.

Real-time PCR

At day 30 after x31 infection, CD69+ or CD69− fractions of CD44hiCD8+ T cells in each tissue were sorted on a FACSAria flow cytometer (BD). Total RNA was prepared using an RNeasy Plus Mini kit (QIAGEN), and cDNA synthesis was performed by using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio Inc.). Quantitative PCR was done on a real-time PCR system (Prism 7900HT; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 96-well plate format with SYBR green–based detection (Takara Bio Inc.). β-actin mRNA was used for normalization. The primers used were: KLF2 forward, 5′-TGTGAGAAATGCCTTTGAGTTTACTG-3′ and KLF2 reverse, 5′-CCCTTATAGAAATACAATCGGTCATAGTC-3′; and S1P1 forward, 5′-GTGTAGACCCAGAGTCCTGCG-3′ and S1P1 reverse, 5′-AGCTTTTCCTTGGCTGGAGAG-3′. mRNA levels in the thymocytes were used as a standard, and relative expression of mRNA was calculated as 2−ΔCt.

Immunofluorescence

At day 18–22 after x31 infection, parabiosis was performed using B6 and Thy1.1 mice. 2 wk later, lung tissues were filled with 300 µl of optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura) through the trachea, harvested, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. 6-µm–thick cryosections were fixed for 2 min with acetone/ethanol, blocked with Blocking One reagent (Nacalai Tesque), and stained with a mixture of antibodies against CD90.1 (BD), CD90.2 (TONBO Bioscience), CD8, CD4, CD103, B220, (BioLegend), pan-cytokeratin, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3; goat polyclonal; R&D Systems) for 30 min at 37°C. Sections were further incubated with secondary antibodies, mounted with Prolong Gold reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and then photographed using a confocal microscope (C2si; Nikon). Cell numbers in each color were counted by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Distances of CD8+ TRM cells from a closest lymph vessel were measured by NIS-Elements software (Nikon).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism (GraphPad Software). Methods of comparison and corrections for multiple comparisons are indicated in each relevant figure legend.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows representative fluorescence micrographs for measuring distances of CD8+ TRM cells from lymph vessels in the lung. Fig. S2 shows representative fluorescence micrographs of i.v. staining, a method used in Fig. 5 E.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Center for Instrumental Analysis, Central Research Facilities (CRF), Kindai University Faculty of Medicine for assistance in flow cytometry; Center for Animal Experiments, CRF for animal care; Center for Recombinant DNA Experiments, CRF for infection experiments; Center of Morphological Analysis, CRF for histology; William Reiley (Trudeau Institute, Saranac Lake, NY) for tetramers; Takashi Nakayama (Kindai University Faculty of Pharmacy, Osaka, Japan) for assistance in chemotaxis assay; Satoshi Ueha (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan) for assistance in parabiosis; members of the Miyazawa laboratory for discussions; and James Brian Dowell for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology with a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists ((A) 24689043 to S. Takamura) and a grant for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (15H01268 to M. Miyazawa) and by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01HL122559 to J.E. Kohlmeier), Takeda Science Foundation (S. Takamura), Daiichi Sankyo Foundation of Life Science (S. Takamura), Uehara Memorial Foundation (S. Takamura), Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science (S. Takamura), and Kindai University Anti-Aging Center (M. Miyazawa).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Conceptualization, S. Takamura; methodology, S. Takamura; validation, S.R. McMaster and J.E. Kohlmeier; formal analysis, S. Takamura; investigation, S. Takamura, H. Yagi, Y. Hakata, C. Motozono, S.R. McMaster, T. Masumoto, M. Fujisawa, T. Chikaishi, J. Komeda, J. Itoh, M. Umemura, and A. Kyusai; resources, M. Tomura, T. Nakayama, and D.L. Woodland; writing (original draft), S. Takamura; writing (review and editing), M. Miyazawa and D.L. Woodland; visualization, S. Takamura; supervision, S. Takamura; project administration, S. Takamura; and funding acquisition, S. Takamura, J.E. Kohlmeier, and M. Miyazawa.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- Ag

- antigen

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- iBALT

- inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue

- i.v.

- intravascular

- LI

- lung interstitium

- LP

- lung parenchyma

- LV

- lung vasculature

- MLN

- mediastinal LN

- NLT

- nonlymphoid tissue

- NP

- nucleoprotein

- ODN

- oligodeoxynucleotide

- PA

- acidic polymerase

- PI

- postinfection

- RAMD

- repair-associated memory depot

- Tg

- transgenic

- TRM cell

- tissue-resident memory T cell

- VEGFR-3

- vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3

References

- Anderson K.G., Sung H., Skon C.N., Lefrancois L., Deisinger A., Vezys V., and Masopust D.. 2012. Cutting edge: intravascular staining redefines lung CD8 T cell responses. J. Immunol. 189:2702–2706. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K.G., Mayer-Barber K., Sung H., Beura L., James B.R., Taylor J.J., Qunaj L., Griffith T.S., Vezys V., Barber D.L., and Masopust D.. 2014. Intravascular staining for discrimination of vascular and tissue leukocytes. Nat. Protoc. 9:209–222. 10.1038/nprot.2014.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariotti S., Beltman J.B., Chodaczek G., Hoekstra M.E., van Beek A.E., Gomez-Eerland R., Ritsma L., van Rheenen J., Marée A.F., Zal T., et al. 2012. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells continuously patrol skin epithelia to quickly recognize local antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:19739–19744. 10.1073/pnas.1208927109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariotti S., Hogenbirk M.A., Dijkgraaf F.E., Visser L.L., Hoekstra M.E., Song J.Y., Jacobs H., Haanen J.B., and Schumacher T.N.. 2014. Skin-resident memory CD8+ T cells trigger a state of tissue-wide pathogen alert. Science. 346:101–105. 10.1126/science.1254803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T., and Bevan M.J.. 2015. Proinflammatory microenvironments within the intestine regulate the differentiation of tissue-resident CD8+ T cells responding to infection. Nat. Immunol. 16:406–414. 10.1038/ni.3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyster J.G., and Schwab S.R.. 2012. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30:69–94. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely K.H., Roberts A.D., and Woodland D.L.. 2003. Cutting edge: effector memory CD8+ T cells in the lung airways retain the potential to mediate recall responses. J. Immunol. 171:3338–3342. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely K.H., Cookenham T., Roberts A.D., and Woodland D.L.. 2006. Memory T cell populations in the lung airways are maintained by continual recruitment. J. Immunol. 176:537–543. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost E.L., Kersh A.E., Evavold B.D., and Lukacher A.E.. 2015. Cutting edge: Resident memory CD8 T cells express high-affinity TCRs. J. Immunol. 195:3520–3524. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt T., Wakim L.M., Eidsmo L., Reading P.C., Heath W.R., and Carbone F.R.. 2009. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat. Immunol. 10:524–530. 10.1038/ni.1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt T., Whitney P.G., Zaid A., Mackay L.K., Brooks A.G., Heath W.R., Carbone F.R., and Mueller S.N.. 2011. Different patterns of peripheral migration by memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Nature. 477:216–219. 10.1038/nature10339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GeurtsvanKessel C.H., Willart M.A., Bergen I.M., van Rijt L.S., Muskens F., Elewaut D., Osterhaus A.D., Hendriks R., Rimmelzwaan G.F., and Lambrecht B.N.. 2009. Dendritic cells are crucial for maintenance of tertiary lymphoid structures in the lung of influenza virus–infected mice. J. Exp. Med. 206:2339–2349. 10.1084/jem.20090410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorova I.L., Panteleev M., and Cyster J.G.. 2010. Lymph node cortical sinus organization and relationship to lymphocyte egress dynamics and antigen exposure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:20447–20452. 10.1073/pnas.1009968107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle S., Dujardin H.C., Bakocevic N., Fleige H., Danzer H., Willenzon S., Suezer Y., Hämmerling G., Garbi N., Sutter G., et al. 2009. Induced bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue serves as a general priming site for T cells and is maintained by dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 206:2593–2601. 10.1084/jem.20091472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann M., and Pircher H.. 2011. E-cadherin promotes accumulation of a unique memory CD8 T-cell population in murine salivary glands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:16741–16746. 10.1073/pnas.1107200108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan R.J., Usherwood E.J., Zhong W., Roberts A.A., Dutton R.W., Harmsen A.G., and Woodland D.L.. 2001a Activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells persist in the lungs following recovery from respiratory virus infections. J. Immunol. 166:1813–1822. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan R.J., Zhong W., Usherwood E.J., Cookenham T., Roberts A.D., and Woodland D.L.. 2001b Protection from respiratory virus infections can be mediated by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells that persist in the lungs. J. Exp. Med. 193:981–986. 10.1084/jem.193.8.981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Lee Y.T., Kaech S.M., Garvy B., and Cauley L.S.. 2015. Smad4 promotes differentiation of effector and circulating memory CD8 T cells but is dispensable for tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 194:2407–2414. 10.4049/jimmunol.1402369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima N., and Iwasaki A.. 2014. A local macrophage chemokine network sustains protective tissue-resident memory CD4 T cells. Science. 346:93–98. 10.1126/science.1257530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelley-Gibbs D.M., Brown D.M., Dibble J.P., Haynes L., Eaton S.M., and Swain S.L.. 2005. Unexpected prolonged presentation of influenza antigens promotes CD4 T cell memory generation. J. Exp. Med. 202:697–706. 10.1084/jem.20050227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelley-Gibbs D.M., Dibble J.P., Brown D.M., Strutt T.M., McKinstry K.K., and Swain S.L.. 2007. Persistent depots of influenza antigen fail to induce a cytotoxic CD8 T cell response. J. Immunol. 178:7563–7570. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Clark R.A., Liu L., Wagers A.J., Fuhlbrigge R.C., and Kupper T.S.. 2012. Skin infection generates non-migratory memory CD8+ TRM cells providing global skin immunity. Nature. 483:227–231. 10.1038/nature10851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan T.N., Mooster J.L., Kilgore A.M., Osborn J.F., and Nolz J.C.. 2016. Local antigen in nonlymphoid tissue promotes resident memory CD8+ T cell formation during viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 213:951–966. 10.1084/jem.20151855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.S., Hufford M.M., Sun J., Fu Y.X., and Braciale T.J.. 2010. Antigen persistence and the control of local T cell memory by migrant respiratory dendritic cells after acute virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 207:1161–1172. 10.1084/jem.20092017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer S., Dethlefsen I., Hagner-Benes S., Marsh L.M., Garn H., and König P.. 2013. Visualization of intrapulmonary lymph vessels in healthy and inflamed murine lung using CD90/Thy-1 as a marker. PLoS One. 8:e55201 10.1371/journal.pone.0055201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P.A., Hu Y., Yamamoto Y., Hoe N.B., Wei T.S., Mu D., Sun Y., Joo L.S., Dagher R., Zielonka E.M., et al. 2011. Distal airway stem cells yield alveoli in vitro and during lung regeneration following H1N1 influenza infection. Cell. 147:525–538. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw B.J., Zhang N., Marshall H.D., Staron M.M., Guan T., Hu Y., Cauley L.S., Craft J., and Kaech S.M.. 2014. CD4+ T cell help guides formation of CD103+ lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells during influenza viral infection. Immunity. 41:633–645. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.T., Suarez-Ramirez J.E., Wu T., Redman J.M., Bouchard K., Hadley G.A., and Cauley L.S.. 2011. Environmental and antigen receptor-derived signals support sustained surveillance of the lungs by pathogen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 85:4085–4094. 10.1128/JVI.02493-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay L.K., Stock A.T., Ma J.Z., Jones C.M., Kent S.J., Mueller S.N., Heath W.R., Carbone F.R., and Gebhardt T.. 2012. Long-lived epithelial immunity by tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells in the absence of persisting local antigen presentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:7037–7042. 10.1073/pnas.1202288109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay L.K., Rahimpour A., Ma J.Z., Collins N., Stock A.T., Hafon M.L., Vega-Ramos J., Lauzurica P., Mueller S.N., Stefanovic T., et al. 2013. The developmental pathway for CD103+CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat. Immunol. 14:1294–1301. 10.1038/ni.2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay L.K., Braun A., Macleod B.L., Collins N., Tebartz C., Bedoui S., Carbone F.R., and Gebhardt T.. 2015a Cutting edge: CD69 interference with sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor function regulates peripheral T cell retention. J. Immunol. 194:2059–2063. 10.4049/jimmunol.1402256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay L.K., Wynne-Jones E., Freestone D., Pellicci D.G., Mielke L.A., Newman D.M., Braun A., Masson F., Kallies A., Belz G.T., and Carbone F.R.. 2015b T-box transcription factors combine with the cytokines TGF-β and IL-15 to control tissue-resident memory T cell fate. Immunity. 43:1101–1111. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay L.K., Minnich M., Kragten N.A., Liao Y., Nota B., Seillet C., Zaid A., Man K., Preston S., Freestone D., et al. 2016. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science. 352:459–463. 10.1126/science.aad2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masopust D., Choo D., Vezys V., Wherry E.J., Duraiswamy J., Akondy R., Wang J., Casey K.A., Barber D.L., Kawamura K.S., et al. 2010. Dynamic T cell migration program provides resident memory within intestinal epithelium. J. Exp. Med. 207:553–564. 10.1084/jem.20090858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMaster S.R., Wilson J.J., Wang H., and Kohlmeier J.E.. 2015. Airway-resident memory CD8 T cells provide antigen-specific protection against respiratory virus challenge through rapid IFN-γ production. J. Immunol. 195:203–209. 10.4049/jimmunol.1402975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., Inami M., Hasegawa A., Kubo S., Kimura M., Yamashita M., Hosokawa H., Nagao T., Suzuki K., Hashimoto K., et al. 2003. CD69-null mice protected from arthritis induced with anti-type II collagen antibodies. Int. Immunol. 15:987–992. 10.1093/intimm/dxg102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasaraju T., Ng H.H., Phoon M.C., and Chow V.T.. 2010. MCP-1 antibody treatment enhances damage and impedes repair of the alveolar epithelium in influenza pneumonitis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 42:732–743. 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0423OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston G.C., Feijoo-Carnero C., Schurch N., Cowling V.H., and Cantrell D.A.. 2013. The impact of KLF2 modulation on the transcriptional program and function of CD8 T cells. PLoS One. 8:e77537 10.1371/journal.pone.0077537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Moreno J., Carragher D.M., de la Luz Garcia-Hernandez M., Hwang J.Y., Kusser K., Hartson L., Kolls J.K., Khader S.A., and Randall T.D.. 2011. The development of inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue depends on IL-17. Nat. Immunol. 12:639–646. 10.1038/ni.2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S.J., Franki S.N., Pierce R.H., Dimitrova S., Koteliansky V., Sprague A.G., Doherty P.C., de Fougerolles A.R., and Topham D.J.. 2004. The collagen binding α1β1 integrin VLA-1 regulates CD8 T cell-mediated immune protection against heterologous influenza infection. Immunity. 20:167–179. 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00021-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaue-Sawano A., Kurokawa H., Morimura T., Hanyu A., Hama H., Osawa H., Kashiwagi S., Fukami K., Miyata T., Miyoshi H., et al. 2008. Visualizing spatiotemporal dynamics of multicellular cell-cycle progression. Cell. 132:487–498. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel J.M., and Masopust D.. 2014. Tissue-resident memory T cells. Immunity. 41:886–897. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel J.M., Fraser K.A., Vezys V., and Masopust D.. 2013. Sensing and alarm function of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 14:509–513. 10.1038/ni.2568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel J.M., Fraser K.A., Beura L.K., Pauken K.E., Vezys V., and Masopust D.. 2014a Resident memory CD8 T cells trigger protective innate and adaptive immune responses. Science. 346:98–101. 10.1126/science.1254536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel J.M., Fraser K.A., and Masopust D.. 2014b Cutting edge: resident memory CD8 T cells occupy frontline niches in secondary lymphoid organs. J. Immunol. 192:2961–2964. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H., and Iwasaki A.. 2012. A vaccine strategy that protects against genital herpes by establishing local memory T cells. Nature. 491:463–467. 10.1038/nature11522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiow L.R., Rosen D.B., Brdicková N., Xu Y., An J., Lanier L.L., Cyster J.G., and Matloubian M.. 2006. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-α/β to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 440:540–544. 10.1038/nature04606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skon C.N., Lee J.Y., Anderson K.G., Masopust D., Hogquist K.A., and Jameson S.C.. 2013. Transcriptional downregulation of S1pr1 is required for the establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 14:1285–1293. 10.1038/ni.2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert E.M., Schenkel J.M., Fraser K.A., Beura L.K., Manlove L.S., Igyártó B.Z., Southern P.J., and Masopust D.. 2015. Quantifying memory CD8 T cells reveals regionalization of immunosurveillance. Cell. 161:737–749. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura S., Roberts A.D., Jelley-Gibbs D.M., Wittmer S.T., Kohlmeier J.E., and Woodland D.L.. 2010. The route of priming influences the ability of respiratory virus–specific memory CD8+ T cells to be activated by residual antigen. J. Exp. Med. 207:1153–1160. 10.1084/jem.20090283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teijaro J.R., Turner D., Pham Q., Wherry E.J., Lefrançois L., and Farber D.L.. 2011. Cutting edge: Tissue-retentive lung memory CD4 T cells mediate optimal protection to respiratory virus infection. J. Immunol. 187:5510–5514. 10.4049/jimmunol.1102243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomura M., Sakaue-Sawano A., Mori Y., Takase-Utsugi M., Hata A., Ohtawa K., Kanagawa O., and Miyawaki A.. 2013. Contrasting quiescent G0 phase with mitotic cell cycling in the mouse immune system. PLoS One. 8:e73801 10.1371/journal.pone.0073801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D.L., Bickham K.L., Thome J.J., Kim C.Y., D’Ovidio F., Wherry E.J., and Farber D.L.. 2014. Lung niches for the generation and maintenance of tissue-resident memory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 7:501–510. 10.1038/mi.2013.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan A.E., Brumwell A.N., Xi Y., Gotts J.E., Brownfield D.G., Treutlein B., Tan K., Tan V., Liu F.C., Looney M.R., et al. 2015. Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature. 517:621–625. 10.1038/nature14112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakim L.M., Woodward-Davis A., and Bevan M.J.. 2010. Memory T cells persisting within the brain after local infection show functional adaptations to their tissue of residence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:17872–17879. 10.1073/pnas.1010201107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakim L.M., Gupta N., Mintern J.D., and Villadangos J.A.. 2013. Enhanced survival of lung tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells during infection with influenza virus due to selective expression of IFITM3. Nat. Immunol. 14:238–245. 10.1038/ni.2525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley J.A., Hogan R.J., Woodland D.L., and Harmsen A.G.. 2001. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells persist in the upper respiratory tract following influenza virus infection. J. Immunol. 167:3293–3299. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Hu Y., Lee Y.T., Bouchard K.R., Benechet A., Khanna K., and Cauley L.S.. 2014. Lung-resident memory CD8 T cells (TRM) are indispensable for optimal cross-protection against pulmonary virus infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 95:215–224. 10.1189/jlb.0313180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaid A., Mackay L.K., Rahimpour A., Braun A., Veldhoen M., Carbone F.R., Manton J.H., Heath W.R., and Mueller S.N.. 2014. Persistence of skin-resident memory T cells within an epidermal niche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:5307–5312. 10.1073/pnas.1322292111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit D.J., Turner D.L., Klonowski K.D., Lefrançois L., and Cauley L.S.. 2006. Residual antigen presentation after influenza virus infection affects CD8 T cell activation and migration. Immunity. 24:439–449. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., and Bevan M.J.. 2013. Transforming growth factor-β signaling controls the formation and maintenance of gut-resident memory T cells by regulating migration and retention. Immunity. 39:687–696. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo W., Zhang T., Wu D.Z., Guan S.P., Liew A.A., Yamamoto Y., Wang X., Lim S.J., Vincent M., Lessard M., et al. 2015. p63+Krt5+ distal airway stem cells are essential for lung regeneration. Nature. 517:616–620. 10.1038/nature13903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.