Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the surgical scars of external dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) cosmetically.

METHODS

Totally 50 consecutive cases of primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction (PANDO) were included in the study. Surgical scars were assessed by the patients and two independent observers at 2, 6 and 12wk postoperatively on the basis of visibility of the scars and still photographs respectively and were graded from 0-3. Kappa test was utilised to check the agreement of scar grading between the two observers. Wilcoxan signed ranks test was used to analyse the improvement of scar grading.

RESULTS

Thirty-four (68%) patients graded their incision site as very visible (grade 3) at 2wk. At 6 and 12wk, incision site was observed as grade 3 by 7 (14%) and 1 (2%) patients respectively. Photographic evaluation of patients by 2 observers showed an average score of 2.75, 1.94 and 0.94 at 2, 6 and 12wk respectively. Change in scar grading from grade 3 to grade 0 in consecutive follow-up (2, 6 and 12wk) was found to be highly significant both for the patient as well for the observers (P<0.0001).

CONCLUSION

The external DCR is a highly effective and safe procedure and in view of low percentage of cases who complained of marked scarring in the present study, thus scarring should not be the main ground for deciding the approach to DCR surgery, even in young cosmetically conscious patients.

Keywords: cosmetic, surgical scar, external dacryocystorhinostomy, primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction

INTRODUCTION

Primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction (PANDO) is a common cause of epiphora in adults, and it is 4-5 times more common in females[1].

The surgical management of epiphora due to PANDO has revolved around creating a dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) with either an external skin incisional approach (EXT)[2] or endoscopically through the nasal mucosa [3]–[4]. DCR is a surgical procedure to remove the obstruction within the lacrimal drainage system[5]. The main indication for surgical intervention is clinically significant persistent epiphora and discharge in the presence of nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

External DCR is an extremely successful operation. The success rate of external DCR has been reported at between 80% and 99% depending on the surgeon's experience[6].

Recent advances in DCR include the techniques of endonasal DCR and laser DCR. In recent years, there has been a considerable interest in the popularity of endonasal and laser DCR compared with conventional external DCR[7]–[9]. This has been possible with the advent of advances in techniques and instrumentation, especially in the fields of endoscopes and video monitors[8]–[9]. The success rate of endonasal and laser DCR has also increased in recent years, the main purported advantage being the absence of a cosmetic scar. A visible skin incision is usually mentioned as one of the disadvantages associated with external DCR and is used as a reason to recommend endonasal or other non-incisional surgical techniques.

However, external DCR is still preferred widely by many surgeons. Since it is highly effective and safe procedure, can be performed in elderly patients under local anaesthesia, with minimal blood loss, and with highest reported success rate[2]. It has an advantage over endoscopic methods especially in cases with an acquired defect, post-traumatic or neoplastic. EXT DCR may be successfully performed even in small hospitals with modest instrument requirement.

Therefore, it is felt that a study regarding the main disadvantage of external DCR, i.e. the external cosmetic scar, is helpful in asserting that the historically established gold standard technique of external DCR still holds its fort over the newer, rapidly emerging favourites of endonasal and endolaser-DCR, and purpose of our study was to evaluate the surgical scar of external DCR cosmetically.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This prospective, clinical interventional study was conducted on 57 consecutive (57 eyes) in-patients of PANDO in a tertiary eye care center. Seven patients were lost to follow-up, so ultimately study was conducted on 50 patients (50 eyes). Informed consent was taken from all the patient who were included in the study. The purpose, method and basis of the study was conveyed to all of the patients recruited. The institutional review board approved the study and we strictly adhered to the tenets of Declaration of Helsinki. Inclusion criteria of the study were all cases of PANDO while exclusion criteria was children less than 12 years old, failed DCR surgery, secondary nasolacrimal duct obstruction [lacrimal sac is involved secondarily following trauma (naso-orbito-ethmoidal fractures, complications of maxillary sinus surgery, rhinoplastic surgery, and midfacial fracture repair), neoplasms (lacrimal sac malignancy) as well as due to pathology in the neighbouring structures like conjunctiva, canaliculi, nose, paranasal air sinuses and pericystic disease], chronic dacrocystitis with fistula and patients unwilling to participate in the study. All the patients were subjected to detailed clinical evaluation to establish the diagnosis of PANDO which includes inspection of the sac area to see any visible sac swelling, regurgitation of sac contents on applying pressure over the sac area, lacrimal syringing, fluorescein dye disappearance test (FDDT) and nasal examination to rule out any contraindication for DCR surgery.

All DCR surgeries were performed under infra trochlear block with intravenous sedation, by a single surgeon. It was performed by a short 10-mm straight incision, positioned at half the distance between the medial canthus and midpoint of the nasal bridge and not extending above the level of the medial canthus. After completion of surgery, orbicularis was closed with 6-0 Vicryl (polyglactin) suture and the skin closed with fine 6-0 Prolene (polypropylene) subcuticular sutures. Skin sutures were removed at 1wk post operatively.

Photograph of each patient were taken at 2, 6 and 12wk post operatively.

Cosmetic assessment of the external DCR scar was done by two methods. The first method includes a post-operative questionnaire to assess the visibility of the scar by the patient himself/herself (scar assessment was done by the patients with the help of mirror), the overall satisfaction with the scar, the willingness of the patient to undergo the same operation again regarding the scar and assessment of the level of discomfort experienced during suture removal (Table 1)[10]. These being assessed at 2, 6 and 12wk post operatively.

Table 1. Questionnaire regarding the cosmetic scar.

| Question | Response | Grade |

| Is your incision site visible? | No | 0 |

| Minimally visible | 1 | |

| Moderately visible | 2 | |

| Maximally visible | 3 | |

| Satisfaction with the scar? | Present | - |

| Absent | - | |

| Considering the scar, will you repeat this procedure again? | Yes | - |

| No | - | |

| Any discomfort experienced during suture removal? | No discomfort | 0 |

| Mild discomfort | 1 | |

| Moderate discomfort | 2 | |

| Severe discomfort | 3 |

The second method of assessment of scar was by two independent observers of same expertise and speciality. Photographs of each patient were randomly shown to 2 observers on 15 inch computer screen with resolution of 1366×768 at 2, 6 and 12wk following surgery. Photographs of each patient were taken under same light condition and technique as described by Devoto et al[10]. The observers were carefully instructed to look for the incision in its appropriate location. The observers rated each photograph by using the following grading: invisible incision (grade 0), minimally visible incision (grade 1), moderately visible incision (grade 2) and very visible incision (grade 3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Photographic grading of scar at 2wk (grade 3), 6wk (grade 1) and 12wk (grade 0).

Statistical Analysis

Sample size was assessed by sample size estimation for proportion. Kappa test was utilised to check the agreement of scar grading between the two observers. The two observers were trained and retrained till the agreement between their observation were graded as substantial by kappa test. Kappa value for agreement was assessed as poor agreement (<0), slight agreement (0-0.2), fair agreement (0.21-0.40), moderate agreement (0.41-0.60), substantial agreement (0.61-0.80) and outstanding agreement (0.81-1). Non parametrical Wilcoxan signed ranks test and the relative risk was used to analyse the improvement of scar grading by patients and observers in consecutive follow ups. Data were analysed using SPSS version 20. A 2-tailed P-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Out of 57 cases, who underwent DCR,7 patients did not turn up for follow up and were excluded from study. So, 50 patients (50 eyes) of PANDO were included in this study In our study, mean age of patients were 42.1±14.6y. Females comprised [39 (78%)] while males comprised [11 (22%)] of the total number of patients. Nineteen (38%) cases were of right side, 31 (62%) cases were of left side. Anatomic success in our study was seen in 48 (96%) cases.

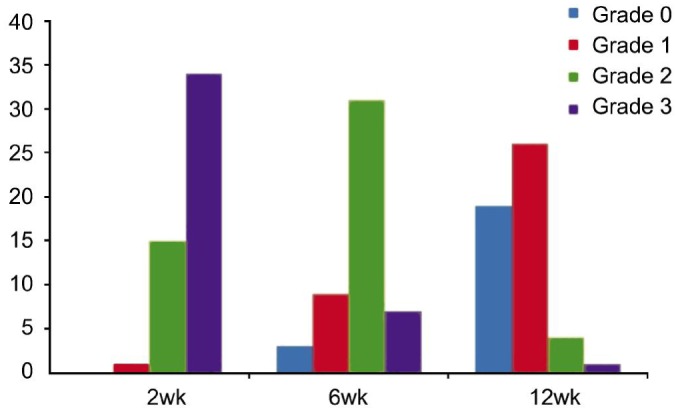

Thirty-four (68%) patients graded their scar maximally visible (grade 3) at 2wk which is reduced to 7 (14%) at 6wk which further reduced to 1 (2%) patient at 12wk. Change in scar grading from grade 3 to grade 0 in consecutive follow-up (2, 6 and 12wk) was found to be highly significant (P<0.0001, Table 2).

Table 2. Questionnaire based scar grading by patients post operatively.

| Grades | 2wk | 6wk | 12wk |

| 0 (Not visible) | 0 | 3 (6) | 19 (38) |

| 1 (Minimally visible) | 1 (2) | 9 (18) | 26 (52) |

| 2 (Moderately visible) | 15 (30) | 31 (62) | 4 (8) |

| 3 (Markedly visible) | 34 (68) | 7 (14) | 1 (2) |

| P | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

n (%)

Relative risk of unacceptable scar (grade 2 and grade 3) between 2 and 12wk was 0.10 (95%CI: 0.04 to 0.23), denoting reducing trend (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Scar grading by patients.

When patients were asked about repeat surgery after taking scar into consideration, 31 (62%) patients does not want to undergo the same procedure at 2wk. However, at the end of 12wk it has reduced to 3 (6%) patients (P<0.001).

Discomfort during suture removal was experienced by only 7 (14%) patients, and they complained only of mild discomfort.

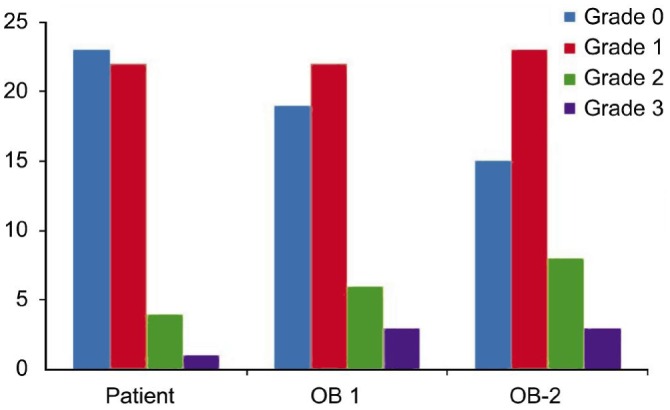

Two independent observers graded the scar at 2, 6 and 12wk postoperatively. Kappa test showed the agreement between the two observers at 2 (0.62), 6 (0.61) and 12wk (0.67). Average score of observer 1 and observer 2 at 2, 6 and 12wk was 2.75 (0.45), 1.94 (0.73) and 0.94 (0.87) respectively showing marked reduction in scar grading. Wilcoxan Signed Ranks test was used to analyse the improvement of scar grading by two independent observers between 2, 6 and 12wk and was found to be highly significant (P<0.0001, Table 3).

Table 3. Post operative scar grading by observers.

| Parameters | 2wk |

6wk |

12wk |

|||

| OB-1 | OB-2 | OB-1 | OB-2 | OB-1 | OB-2 | |

| Grade 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 19 (38) | 15 (30) |

| Grade 1 | 1 (2) | 0 | 10 (20) | 11 (22) | 22 (44) | 23 (46) |

| Grade 2 | 10 (20) | 13 (26) | 26 (52) | 29 (58) | 6 (12) | 8 (16) |

| Grade 3 | 39 (78) | 37 (74) | 12 (24) | 9 (18) | 3 (6) | 4 (8) |

| x±s | 2.76±0.47 | 2.74±0.44 | 1.96±0.7 | 1.92±0.69 | 0.86±0.85 | 1.02±0.89 |

| Mean | 2.75 (0.45) | 1.94 (0.73) | 0.94 (0.87) | |||

| P | <0.0001 | |||||

OB: Observer.

n (%)

Relative risk of unacceptable scar (grade 2 and grade 3) between 2 and 12wk was 0.27 (95%CI: 0.18 to 0.41) showing marked reduction in scar grading.

Patients satisfaction level regarding scar grading was compared with the observers at 12wk. It was found that 80% of the patients were satisfied with their scar (grade 0 and grade 1). Similarly, satisfactory scar grading (grade 0 and grade 1) was also given by observer 1 (82%) and observer 2 (76%) at 12wk, postoperatively (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of scar by patients and observer at 12wk OB: Observer.

DISCUSSION

DCR surgery through an external approach has been the gold standard for the treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction with a success rate of over 90%[11]. External DCR is technically easier, with an unimpaired view of the surgical area and well-defined landmarks allowing the creation of a wide bony window and the use of mucosal flaps to obtain an epithelialized DCR tract[12]. For these reasons and due to its high success rate, external DCR is the preferred primary procedure. However, the presence of a cutaneous scar has been reported as the major disadvantage of an external DCR from the patient's perspective. Previous studies about DCR have shown that patient satisfaction may not necessarily correlate with objective success rates and in case of cutaneous scar, only reliable way to ascertain the significance of the scar is from patient feedback[13]. Mathew et al[14] described “patient satisfaction” in a retrospective study and telephone questionnaire comparing non-laser endoscopic DCR and external DCR, and found no significant difference between the two for patient satisfaction (75% vs 86%, respectively).

However no such scale is available for grading external-DCR scar. Therefore a standardized approach to assess the cosmetic significance of the external DCR scar is the order of the day and we undertook this study to assess the cosmetic significance of the scar in DCR patients, postoperatively.

Although the Vancouver assessment scale is often used to assess burn scars. Studies that compared the patient and observer scar assessment scale (POSAS) with the widely used Vancouver Scar Scale revealed that the former was more reliable than the latter[15]. At present, the POSAS is being used to evaluate the rehabilitation process in different types of injury and has been advocated by many for scar assessment[16]–[17]. Lately, the Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale was proposed. It includes 5 parameters (width, height, colour, suture marks, overall appearance) and a total score of 0-5 points, where increasing score correlates to scar healing[18].

In the literature, various skin incisions have been described for external DCR[19]–[22].

Langer et al[23] described the normal tensile strength lines of the skin and reported that the direction of the incision line was one of the most important factors determining final scar formation. Borges emphasizes the importance of obtaining relaxed tensile strength lines at the skin incision and recommends that the incision should be performed parallel to the tensile strength lines[24].

Sharma et al[25] studied to evaluate the significance of the surgical scar of external DCR as assessed by the patients. Totally 20.6% scars were felt to be visible by patient, 10.5% were rated >1 on a scale of 1-5 and 4% were rated >2. The average age of patients was highest for those patients with invisible scars, and the lowest average age was for those with scars that were rated >1.

Devoto et al[10] evaluated the appearance of the skin incision in external DCR 6wk and 6mo after surgery. Six weeks after surgery, 26% patients could not see their incision site (grade 0) and 9% graded it as very visible (grade 3). Six percent of the patients were not satisfied with the appearance of the incision. Six months after surgery, 44% patients could not see their incision site (grade 0) and no patient graded it as very visible. All patients were satisfied with the appearance of their incision.

Dave et al[19] studied subciliary incision for external DCR and showed objective grading of the scar by the physician was 88.2% (grade 0-1) and subjective scar grading by the patient were100% (grade 0-1) at the final follow up.

Ekinci et al[26] compared the effect of W-shaped skin (WS) and linear skin (LS) incisions on cutaneous scar tissue formation in two separate patients groups who have undergone external DCR. Self-assessment scores for the incision scar were grade 2.28±0.94 in the Vertical incision group, and grade 1.68±0.57 in the “W incision” group (P <0.01) while the mean scar assessment scores by independent observer were grade 2.13±0.95 in the Vertical incision group, and grade 1.57±0.68 in the “W incision” group (P <0.01).

In another study, they minimized patient related factors by performing LS and WS incisions in the same patient group, and showed that WS incision is a good alternative to LS incision for reducing scar formation after external DCR[27].

Another study showed minimum incision (5 mm) no skin suture Ext-DCR offers high patient satisfaction and success rates. Mean patient satisfaction score for the appearance of incision was 99.2[28]. Recently, a study compared “V-incision” external DCR with conventional approach and concluded that both approaches has a similar functional success rate but “V-incision” external DCR has superior aesthetic outcomes as reported by surgeons and patients[29].

In another study, they minimized patient related factors by performing LS and WS incisions in the same patient group, and shows that WS incision is a good alternative to LS incision for reducing scar formation after external DCR[26].

In the present study, post operative scar assessment was done at 2, 6 and 12wk and result were comparable with the above mentioned studies. At 2wk, 68% patient graded there scar as marked which reduced to 14% at 6wk and it further reduced to 2% at 12wk (P<0.0001). Change in scar grading from grade 3 to grade 0 in consecutive follow up was also highly significant (P<0.0001). The relative risk between 2wk and 12wk for unacceptable scars (grade 2 and grade 3) shows a significant reduction (relative risk, 0.10: 95%CI: 0.04 to 0.23 ).

Photographic evaluation of patients for grading of the scar by two independent observers was done at 2, 6 and 12wk postoperatively. At 2wk, observer 1 and observer 2 graded 76% scars as marked (grade 3) which reduced to 21% at 6wk and it further reduced to 7% at 12wk respectively (P<0.0001). Average score of observers at 2, 6 and 12wk showed marked reduction in scar grading (P<0.0001). The relative risk between 2wk and 12wk for unacceptable scars (grade 2 and grade 3) shows a significant reduction (relative risk, 0.27: 95%CI: 0.18 to 0.41).

When patients were asked about repeat surgery regarding scar only 6% of patients does not want to undergo the same procedure at 12wk. Discomfort during suture removal was experienced by 14% of patients, and they complained only of mild discomfort. There was definitely no reason for them to undergo the same surgery again or refer their friends for the same procedure.

The mean age in our study was 42.1±14.6y which was similar to study done by Ekinci et al[27] (40.8±14.3y) and Dave et al[19] (41.75y) which also showed less scarring in this age group. However, age in our study was much lower than the study reported by Devoto et al[10] (61y), Sharma et al[25] (67y) and more recently by Kashkouli and Jamshidian-Tehrani[28] (52.9y). Further, Kearney et al[30] and Caesar et al[31]suggested more pronounced scarring in young patients and Caesar et al[31] suggested that the high scores in younger patients may come from their otherwise smoother and less flawed skin and good visual acuity, which allows them to observe scar formation more easily[30]–[31]. But in our study less scarring was seen in younger age group which may be due to meticulous suturing of two layers i.e. orbicularis and skin. Similarly, Ciftci et al[32] reported less visible scar in lateral nasal sidewall incision with closure of the lacrimal diaphragm compared to skin only closure.

Though numerous studies has been done in the past on external DCR scars but majority of these studies belong to Caucasian population. This study is the first of its kind which originate from Indian subcontinent and studied the conventional DCR scars. In the present study, the skin incision in external DCR is satisfactory in most patients. Its appearance improved with time. At 12wk, 80%, 82% and 76% of the incisions were graded cosmetically good (grade 0 and grade 1) by patients, observer 1 and observer 2 respectively.

However, limitation of our study is that it is a simple grading scale which neglected other parameters of scar assessment such as width, height, pigmentation, colour and suture marks of considered in other validated studies[15]–[18].

External DCR is noted to be a very successful procedure. It remains the preferred primary procedure in the treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction and chronic dacryocystitis. An additional benefit to the classic external DCR is that it does not require expensive high technology equipment and can therefore be performed in places with developing medical infrastructure. Where access to endoscopic equipment is available, endonasal DCR can serve as an alternative primary or secondary procedure though it is not preferred when simultaneous lacrimal biopsy is required.

However, external DCR remains the primary operation of choice in developing countries due to its low cost, high success rate, reasonable operative time and patient comfort[33]. Thus in light of above results, we concluded that external DCR is a highly effective and safe procedure in PANDO as well as in failed DCR and traumatic nasolacrimal duct obstruction in which naso-orbito-ethmoidal fracture is the main cause and better surgical outcome has been reported with external DCR with or without intubation[34]–[35].

Also in view of low percentage of cases who complained of marked scarring in the present study, thus scarring should not be the main ground for deciding the approach to DCR surgery, even in young cosmetically conscious patients.

Acknowledgments

Part of the manuscript has been presented in Asia Pacific Society of Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery and Silver Jubilee Meeting of Oculoplastics Association of India 2014, New Delhi and 73rd All India Ophthalmological Conference 2015, New Delhi.

Conflicts of Interest: Rizvi SAR, None; Saquib M, None; Maheshwari R, None; Gupta Y, None; Iqbal Z, None; Maheshwari P, None

REFERENCES

- 1.Walker RA, Al-Ghoul A, Conlon MR. Comparison of nonlaser nonendoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy with external dacryocystorhinostomy. Can J Ophthalmol. 2011;46(2):191–195. doi: 10.3129/i10-096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarbet KJ, Custer PL. External dacryocystorhinostomy: surgical success, patient satisfaction, and economic cost. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(7):1065–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30910-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benger R, Forer M. Endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: primary and secondary. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1993;21(3):157–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massaro BM, Gonnering RS, Harris GJ. Endonasal laser dacryocystorhinostomy. A new approach to nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(8):1172–1176. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070100128048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carifi M, Zuberbuhler B, Carifi G. Efficacy of external and endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. J Craniofacial Surg. 2012;23(5):1582–1583. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31825877dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walland MJ, Rose GE. Factors affecting the success rate of open lacrimal surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:888–891. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.12.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benger R. Day-surgery external dacryocystorhinostomy. Aust N Z Ophthalmol. 1992;20(3):243–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1992.tb00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy MT. Advances in lacrimal surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11(5):352–356. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakri SJ, Carney AS, Robinson K, Jones NS, Downes RN. Quality of life outcomes following dacryocystorhinostomy: external and endonasal laser techniques compared. Orbit. 1999;18(2):83–88. doi: 10.1076/orbi.18.2.83.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devoto MH, Zaffaroni MC, Bernardini FP, de Conciliis C. Postoperative evaluation of skin incision in external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20(5):358–361. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000134274.46764.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsirbas A, Davis G, Wormald PJ. Mechanical endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy versus external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20(1):50–56. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000103006.49679.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolman PJ. Comparison of external dacryocystorhinostomy with nonlaser endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(1):78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01452-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibrahim HA, Batterbury M, Banhegyi G, McGalliard J. Endonasal laser dacryocystorhinostomy and external dacryocystorhinostomy outcome profile in a general ophthalmic service unit: a comparative retrospective study. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2003;32(3):220–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathew MR, McGuiness R, Webb LA, Murray SB, Esakowitz L. Patient satisfaction in our initial experience with endonasal endoscopic non-laser dacryocystorhinostomy. Orbit. 2004;23(2):77–85. doi: 10.1080/01676830490501415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powers PS, Sarkar S, Goldgof DB, Cruse CW, Tsap LV. Scar assessment: current problems and future solutions. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20(1 Pt 1):54–60. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199901001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roques C, Teot L. A critical analysis of measurements used to assess and manage scars. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 1999;6(4):249–253. doi: 10.1177/1534734607308249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truong PT, Lee JC, Soer B, Gaul CA, Olivotto IA. Reliability and validity testing of the patient and observer scar assessment scale in evaluating linear scars after breast cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(2):487–494. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000252949.77525.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singer AJ, Arora B, Dagum A, Valentine S, Hollander JE. Developement and validation of a novel scar evaluation scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(7):1982–1987. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000287275.15511.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dave TV, Javed Ali M, Sravani P, Naik MN. Subciliary incision for external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(5):341–345. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31825e697c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutman J, Shinder R. Re: “Transconjunctival dacryocystorhinostomy: scarless surgery without endoscope and laser assistance”. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27(6):465–466. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31822f960e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mjarkesh MM, Morel X, Renard G. Study of the cutaneous scar after external dacryocystorhinostomy. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2012;35(2):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaynak-Hekimhan P, Yilmaz OF. Transconjunctival dacryocystorhinostomy: scarless surgery without endoscope and laser assistance. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27(3):206–210. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181e9a361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langer K. On the anatomy and physiology of the skin. The cleavability of the cutis. Br J Plast Surg. 1978;31(1):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borges AF. Relaxed skin tension lines. Dermatol Clin. 1989;7(1):169–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma V, Martin PA, Benger R, Kourt G, Danks JJ, Deckel Y, Hall G. Evaluation of the cosmetic significance of external dacryocystorhinostomy scars. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):359–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekinci M, Cagatay HH, Oba ME, Yazar Z, Kaplan A, Gökçe G, Keleş S. The long-term follow-up results of external dacryocystorhinostomy skin incision scar with “w incision”. Orbit. 2013;32(6):349–355. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2013.822898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekinci M, Cagatay HH, Gokce G, Ceylan E, Keleş S, Cakici O, Oba ME, Yazar Z. Comparison of the effect of W-shaped and linear skin incisions on scar visibility in bilateral external dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:415–419. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S57382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kashkouli MB, Jamshidian-Tehrani M. Minimum incision no skin suture external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(5):405–409. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng DS, Chan E, Yu DK, Ko ST. Aesthetic assessment in periciliary “v-incision” versus conventional external dacryocystorhinostomy in Asians. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;253(10):1783–1790. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kearney CR, Holme SA, Burden AD, McHenry P. Longterm patient satisfaction with cosmetic outcome of minor cutaneous surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42(2):102–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caesar RH, Fernando G, Scott K, McNab AA. Scarring in external dacryocystorhinostomy: fact or fiction? Orbit. 2005;24(2):83–86. doi: 10.1080/01676830590926567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciftci F, Dinc UA, Ozturk V. The importance of lacrimal diaphragm and periosteum suturation in external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(4):254–258. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181bb5942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yakopson VS, Flanagan JC, Ahn D, Luo BP. Dacryocystorhinostomy: history, evolution and future directions. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2011;25(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rizvi SA, Sharma SC, Tripathy S, Sharma S. Management of traumatic dacryocystitis and failed dacryocystorhinostomy using silicone lacrimal intubation set. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63(3):264–268. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0230-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukherjee B, Dhobekar M. Traumatic nasolacrimal duct obstruction: clinical profile, management, and outcome. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013;23(5):615–622. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]