Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of nitrous oxide-sedated endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration.

METHODS

Enrolled patients were divided randomly into an experimental group (inhalation of nitrous oxide) and a control group (inhalation of pure oxygen) and heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, blood pressure, electrocardiogram (ECG) changes, and the occurrence of complications were monitored and recorded. All patients and physicians completed satisfaction questionnaires about the examination and scored the process using a visual analog scale.

RESULTS

There was no significant difference in heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, blood pressure, ECG changes, or complication rate between the two groups of patients (P > 0.05). However, patient and physician satisfaction were both significantly higher in the nitrous oxide compared with the control group (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION

Nitrous oxide-sedation is a safe and effective option for patients undergoing endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasonography, Nitrous oxide, Sedation, Fine needle aspiration

Core tip: Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has been widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal tract and pancreaticobiliary diseases. However, EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is a time-consuming procedure associated with pain and discomfort. Nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, is a colorless, short-acting inhaled agent that can produce anesthetic, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects. Safety and efficacy of nitrous oxide-sedated EUS-FNA. However, inhaled nitrous oxide has no effect on heart or lung function and patients remain awake, and this thus represents a feasible mode of sedation for EUS. The current study aimed to establish the safe.

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has been widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal tract and pancreaticobiliary diseases. However, EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA)[1-6] is a time-consuming procedure associated with pain and discomfort. Painless EUS can reduce patient suffering and thus make patients more likely to accept the examination. Intravenous anesthetic agents including benzodiazepine-opioid drugs and propofol are commonly used, but their respiratory-inhibitory effects limit their application[7]. Furthermore, most EUS procedures require water injection into the digestive tract, which increases the risk of aspiration during anesthesia. Nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, is a colorless, short-acting inhaled agent that can produce anesthetic, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects. However, inhaled nitrous oxide has no effect on heart or lung function and patients remain awake, and this thus represents a feasible mode of sedation for EUS[7]. The current study aimed to establish the safety and efficacy of nitrous oxide-sedated EUS-FNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

The inclusion criteria for the study were patients who required EUS-FNA and agreed to sedation with nitrous oxide. Patients were excluded if they exhibited any of the following contraindications to nitrous oxide sedation or EUS: (1) intending to get pregnant or in the first trimester of pregnancy; (2) coma; (3) within 1 wk of gas cerebral angiography; (4) diving diseases or a recent history of diving activities; (5) middle ear diseases; (6) pneumothorax, pulmonary cystic fibrosis, or chronic debilitating weakness due to other respiratory disorders; (7) intestinal obstruction; (8) history of gastrointestinal surgery; (9) history of sinus or nasal-septum surgery; (10) need for endoscopic treatment; (11) American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grade > 3; and (12) blood oxygen saturation < 95% and systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg as displayed on the monitor.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of China Medical University (clinical trial registration number: ChiCTR-OCC-15005853). All patients voluntarily provided written informed consent for their participation in this study. The operator performing the EUS-FNA procedure in this study was familiar with the technique.

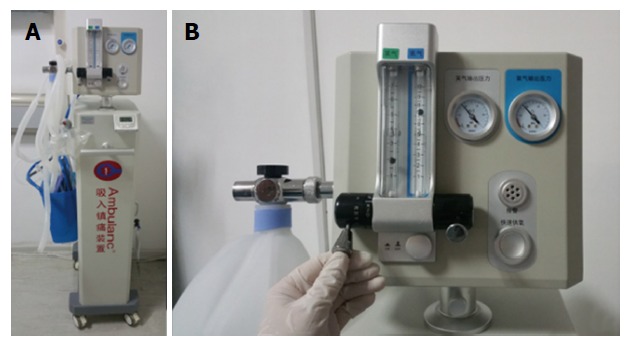

Equipment

The following equipment was used: a nitrous oxide sedation system (AII 5000C; Shenzhen Security Technology Co., Ltd., China) (Figure 1); a patient monitor (PM-7000; Mindray); an ultrasound scanner (EUB 6500, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan); a linear array echo-endoscope (Pentax EG3830UT, Japan); and a 22-gauge needle (EUS N-22-T, Wilson-Cook, United States).

Figure 1.

Nitrous oxide sedation system (AII 5000C; Shenzhen Security Technology Co., Ltd., China).

Study design

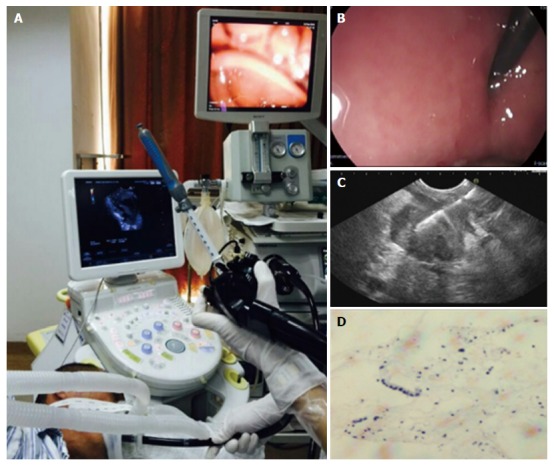

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical study. The patients were divided into an experimental group and control group using a random-number table. The experimental group received nitrous oxide inhalation, with the inspiratory flow of nitrous oxide adjusted according to the depth of sedation (range of nitrous oxide concentrations 30%-70%). The control group received oxygen inhalation at a concentration of 100% and flow rate of 2-3 L/min. Patients were placed in the left lateral recumbent position during the endoscopic procedure and EUS-FNA was performed using a linear array echo-endoscope (Figure 2). This was a single-blind study and the patients were unaware of the identity of the inhaled gas. Patients with unsuccessful EUS were excluded from the current study.

Figure 2.

Patients were placed in the left lateral recumbent position during the endoscopic procedure and endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration was performed using a linear array echo-endoscope. A: Patients were placed in the left lateral recumbent position during the endoscopic procedure and endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration was performed using a linear array echo-endoscope; B: A 22G needle was used to puncture the pancreatic lesion; C: The lesion was in the body of the pancreas; D: The diagnosis of histology was adenocarcinoma.

Patient monitoring

This study trained auxiliary nurses who adjusted the inhalation flow of nitrous oxide during the endoscopic operation, under the guidance of a physician, and who provided nursing care for the patients. All the physicians in this study were trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and tracheal intubation, ensuring that patients received timely basic cardiac life support. Patients’ blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and heart rates were monitored closely, and the monitor set off an alarm if the oxygen saturation dropped to < 95% or the heart rate decreased to < 50 beats/min (bpm). Blood pressure was measured automatically every 3 min, and the monitor alarm went off if the systolic blood pressure was < 90 mmHg. Continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring was performed in all patients. The auxiliary nurse helped to observe patients’ thoracic movements and respiratory rates, and assisted endoscopic physicians to adjust the nitrous oxide inhalation flow promptly according to the depth of sedation, the specific circumstances of the patients, and examination during endoscopic operation. The auxiliary nurses were also responsible for monitoring the patients until 10 min after the termination of nitrous oxide inhalation to ensure that their vital signs were stable.

Safety evaluation

Patients were monitored closely and the following negative events were recorded: oxygen desaturation (oxygen saturation < 95%, but ≥ 90%), hypoxia (oxygen saturation < 90%, but ≥ 85%), severe hypoxemia (oxygen saturation < 85%), hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg), bradycardia (heart rate < 50 bpm), and tachycardia (heart rate > 120 bpm).

Patients and endoscopists completed questionnaires regarding their degree of satisfaction with the examination process, and scored them on a visual analog scale (VAS) scale. The following questions were included: (1) evaluation of the operation by the endoscopist: (smooth, ordinary, not smooth); (2) patient discomfort during the operation process (slight, moderate, severe); (3) patient tolerance with the examination process (good, medium, and low); and (4) willingness to receive the same examination again if needed (yes, no).

Treatment of complications

The endoscopy procedure was suspended and the inhalation of nitrous oxide in the experimental group was reduced or suspended and replaced by inhalation of pure oxygen if the patients experienced blood oxygen saturation < 95%, systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg, or a heart rate < 50 bpm. If the above parameters were immediately restored to normal levels, the operation was continued and patients in the experimental group were given inhalational nitrous oxide at a slightly reduced flow rate than before. However, if the above-mentioned parameters persisted for > 1 min, the operation was terminated. If patients in the experimental group showed signs of excessive inhalation, nitrous oxide was reduced or terminated and replaced by oxygen inhalation. Signs of excessive inhalation of nitrous oxide included the following: disappearance of original signs of comfort and relaxation; new or sudden intolerance, dizziness, vertigo, agitation, or irritability; repeated or ambiguous words and poor response to verbal commands; fixation of eyes and unresponsiveness; sleepiness and difficulty keeping eyes open, or drowsy; dreaming or fantasizing; uncontrolled laughter; stopping breathing; or nausea and vomiting.

Statistical analysis

All the measured data were presented as means. All analyses were performed using SPSS 16 statistical software.

RESULTS

A total of 2877 patients required EUS examinations from March 1 2015 to May 31 2016, of whom 42 patients who required EUS-FNA were enrolled in the study (1.5%) according to the above criteria. There were 21 patients in the control group (pure oxygen group) and 21 patients in the experimental group (nitrous oxide group). There was no significant difference in ASA, age, or sex between the two groups. One patient failed to finish the EUS examination (difficulty in passing through the throat), and was excluded from the current study. The remaining 41 patients (20 in the control group and 21 in the experimental group) completed the examination and the relevant questionnaires, including 16 women and 25 men, average age 42.4 years, (range, 27-69 years). The average time to completion of EUS-FNA was 29 min (range, 14-47 min). The maximal concentration of nitrous oxide used varied among cases and ranged from 30%-70%.

The ECG monitoring results are shown in Table 1. Among the 21 patients in the nitrous oxide group who completed the examination, one patient (4.8%) experienced temporary oxygen desaturation and one experienced hypoxemia (4.8%). The symptoms resolved immediately after termination of nitrous oxide inhalation and inhalation of pure oxygen, with no decline in oxygen saturation after the restart of nitrous oxide inhalation. No patients developed severe hypoxemia, bradycardia (heart rate < 50 bpm), systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg during the examination process, or tachycardia (heart rate > 120 bpm). There was no significant difference in heart rate, oxygen saturation level, or ECG changes between the two groups.

Table 1.

Electrocardiogram changes in patients during examination

| Group |

Heart rate |

Oxygen saturation |

Significant change in electrocardiogram | |||

| > 120 bpm | < 50 bpm | Oxygen desaturation | Hypoxia | Severe hypoxia | ||

| Experimental | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Control | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| P value | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 |

The results of the questionnaires completed by the physicians and patients are listed in Table 2 and the VAS scores are listed in Table 3. All physicians and patients completed the questionnaires. Physician and patient satisfaction with the examination process was significantly higher in the nitrous oxide group compared with the pure oxygen group (patient scores 87 vs 72, t = 4.702, P < 0.05; physician scores 91 vs 70, t = 10.163, P < 0.05). Among the 21 patients in the nitrous oxide group, 18 (85.7%) were willing to receive the same examination again if required, compared with only 9 of 20 (45%) in the control group.

Table 2.

Results of questionnaire

| Group |

Evaluation by physicians |

Patient discomfort |

Patient tolerance |

||||||

| Steady | Ordinary | Not steady | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Good | Medium | Poor | |

| Experimental | 17 | 3 | 1 | 18 | 2 | 1 | 18 | 3 | 0 |

| Control | 11 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 7 |

| P value | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |||

Table 3.

Patient and physician visual analog scale scores for examination process

| Group | Patient satisfaction score | Physician satisfaction score | Willing to receive same examination again n (%) |

| Experimental | 87 | 91 | 18 (85.7) |

| Control | 72 | 70 | 9 (45) |

| P value | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

DISCUSSION

EUS has been widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of digestive tract diseases. It can get closer to the common bile duct and pancreas than transabdominal ultrasound, thus avoiding interference from digestive tract gases and resulting in clearer imaging, and is considered to be preferable to computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of small pancreatic lesions. Numerous studies have demonstrated unique advantages of EUS for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Furthermore, EUS-FNA is the first choice of diagnostic procedure in many diseases, such as pancreatic, gastrointestinal subepithelial, and mediastinal lesions[1-6]. However, the use of a long hard endoscope means that it is much more uncomfortable than general gastroscopy, and cannot be tolerated by some patients. Although EUS can be performed under intravenous propofol anesthesia, some lesions can only be displayed clearly after gastric infusion of water, which increases the risk of aspiration during intravenous propofol anesthesia. The success rate of EUS could therefore be improved by establishing a method for reducing pain and discomfort and increasing patient tolerance.

Nitrous oxide is an inhaled sedative and analgesic agent, which passes through the blood-brain barrier into the brain and functions by inhibiting excitatory neurotransmitter release and nerve impulse conduction in the central nervous system, and altering the permeability of ion channels. Nitrous oxide does not stimulate the respiratory tract or bind to hemoglobin, and does not cause respiratory depression or damage heart, lung, liver, or kidney function. Nitrous oxide sedation is currently used widely in clinical situations, including in emergency surgery, dentistry, childbirth, abortion and curettage, and pediatrics, and can also be applied for gastrointestinal endoscopic sedation. Nitrous oxide-sedated endoscopy examinations have been shown to be safe and effective[8-22], and nitrous oxide has proven a safe and effective choice for colonoscopy sedation and analgesia[8-10,12,17,19-22]. However, nitrous oxide is rarely used for EUS. Lan et al[8] compared the diagnostic accuracy, safety, complications, and patient and examiner satisfaction among different sedation approaches in patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Patients in the nitrous oxide sedation group reported greater satisfaction with the endoscopy procedure than patients in the conventional group (no sedation), with overall better tolerance and less pain, nausea, and vomiting (P < 0.05). A review of 11 studies by Welchman et al[9] concluded that nitrous oxide provided comparable analgesia to intravenous sedation for patients undergoing colonoscopy. Wang et al[10] first mentioned the use of nitrous oxide in EUS, and concluded that it offered a comfortable, safe and feasible option, especially for procedures requiring irrigation. Michaud and Gottrand[13] showed that the time taken to regain consciousness was short following nitrous oxide sedation, which could effectively meet the sedative requirements for children undergoing gastroscopic examination, thus providing a valuable alternative method of sedation. Michaud et al[14] compared the sedative effects of propofol and nitrous oxide in patients undergoing colonoscopy, and showed that both agents had similar sedative and pain-relieving effects, facilitated the operation, and shortened recovery time. In addition, nitrous oxide has demonstrated minimal effects on nerve function and therefore does not affect the patient’s ability to drive[15].

In this study, we monitored heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and ECG in patients undergoing EUS under nitrous oxide sedation. Nitrous oxide had minimal effects on all these parameters, similar to the effects of pure oxygen. Patient and endoscopist satisfaction surveys and VAS scores indicated that the use of nitrous oxide significantly increased patient tolerance to EUS. Nitrous oxide sedation therefore represents a safe and effective choice in patients undergoing EUS-FNA.

COMMENTS

Background

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has been widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal tract and pancreaticobiliary diseases. However, EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is a time-consuming procedure associated with pain and discomfort. Nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, is a colorless, short-acting inhaled agent that can produce anesthetic, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects. However, inhaled nitrous oxide has no effect on heart or lung function and patients remain awake, and this thus represents a feasible mode of sedation for EUS. The current study aimed to establish the safety and efficacy of nitrous oxide-sedated EUS-FNA.

Research frontiers

Nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, is a colorless, short-acting inhaled agent that can produce anesthetic, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects. However, inhaled nitrous oxide has no effect on heart or lung function and patients remain awake, and this thus represents a feasible mode of sedation for EUS. It is the first time to establish the safety and efficacy of nitrous oxide-sedated EUS-FNA.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Nitrous oxide-sedated endoscopy examinations have been shown to be safe and effective, and nitrous oxide has proven a safe and effective choice for colonoscopy sedation and analgesia. However, nitrous oxide is rarely used for EUS. In this study, the authors monitored heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and electrocardiogram (ECG) in patients undergoing EUS under nitrous oxide sedation. Nitrous oxide had minimal effects on all these parameters, similar to the effects of pure oxygen. Patient and endoscopist satisfaction surveys and visual analog scale (VAS) scores indicated that the use of nitrous oxide significantly increased patient tolerance to EUS.

Applications

In this study, the authors monitored heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and ECG in patients undergoing EUS under nitrous oxide sedation. Nitrous oxide had minimal effects on all these parameters, similar to the effects of pure oxygen. Patient and endoscopist satisfaction surveys and VAS scores indicated that the use of nitrous oxide significantly increased patient tolerance to EUS. Nitrous oxide sedation therefore represents a safe and effective choice in patients undergoing EUS-FNA.

Terminology

Nitrous oxide-sedation is a safe and effective option for patients undergoing endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration.

Peer-review

This is an interesting study about the safety and efficacy of nitrous oxide-sedated endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for digestive tract diseases.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of China Medical University (clinical trial registration number: ChiCTR-OCC-15005853).

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: October 19, 2016

First decision: November 14, 2016

Article in press: December 2, 2016

P- Reviewer: Ismail M, Kesavadevi J S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Alkaade S, Chahla E, Levy M. Role of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology, viscosity, and carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic cyst fluid. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:299–303. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rana SS, Sharma V, Sharma R, Gunjan D, Dhalaria L, Gupta R, Bhasin DK. Gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor mimicking cystic tumor of the pancreas: Diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-fine-needle aspiration. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:351–352. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma M, Rafiq A, Kirnake V. Dysphagia due to tubercular mediastinal lymphadenitis diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:348–350. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baysal B, Masri OA, Eloubeidi MA, Senturk H. The role of EUS and EUS-guided FNA in the management of subepithelial lesions of the esophagus: A large, single-center experience. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015 doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.155772. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parekh PJ, Majithia R, Diehl DL, Baron TH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:85–91. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.156711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohri D, Nakai Y, Isayama H, Koike K. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma diagnosed by EUS-guided tissue acquisition. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:353–354. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maslekar S, Gardiner A, Hughes M, Culbert B, Duthie GS. Randomized clinical trial of Entonox versus midazolam-fentanyl sedation for colonoscopy. Br J Surg. 2009;96:361–368. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lan C, Shen X, Cui H, Liu H, Li P, Wan X, Lan L, Chen D. Comparison of nitrous oxide to no sedation and deep sedation for diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1066–1072. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welchman S, Cochrane S, Minto G, Lewis S. Systematic review: the use of nitrous oxide gas for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:324–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Sun S, Liu X, Guo J, Wang S, Wang G. Safety and efficacy of nitrous oxide for endoscopic ultrasound procedures that need irrigation. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3:S14–S15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQuaid KR, Laine L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:910–923. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froehlich F, Harris JK, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, Vader JP, Gonvers JJ. Current sedation and monitoring practice for colonoscopy: an International Observational Study (EPAGE) Endoscopy. 2006;38:461–469. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin JP, Sexton BF, Saunders BP, Atkin WS. Inhaled patient-administered nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture does not impair driving ability when used as analgesia during screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:701–703. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.106113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michaud L, Gottrand F, Ganga-Zandzou PS, Ouali M, Vetter-Laffargue A, Lambilliotte A, Dalmas S, Turck D. Nitrous oxide sedation in pediatric patients undergoing gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:310–314. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199903000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forbes GM, Collins BJ. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy: a randomized controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:271–277. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harding TA, Gibson JA. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for flexible sigmoidoscopy: a placebo-controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2000;32:457–460. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maslekar SK, Hughes M, Skinn E, Graeme Duthie. Randomised controlled trial of sedation for colonoscopy: entonox versus intravenous sedation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB97. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calleary JG, Masood J, Van-Mallaerts R, Barua JM. Nitrous oxide inhalation to improve patient acceptance and reduce procedure related pain of flexible cystoscopy for men younger than 55 years. J Urol. 2007;178:184–188; discussion 188. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Løberg M, Furholm S, Hoff I, Aabakken L, Hoff G, Bretthauer M. Nitrous oxide for analgesia in colonoscopy without sedation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1347–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao AS, Baron TH. Endoscopy: Nitrous oxide sedation for colonoscopy-no laughing matter. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:539–541. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fink SD, Schutz SM. Immediate recovery of psychomotor function after patient-administered nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:201–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trojan J, Saunders BP, Woloshynowych M, Debinsky HS, Williams CB. Immediate recovery of psychomotor function after patient-administered nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation for colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:17–22. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]