Abstract

Ethics is key to the integrity of the veterinary profession. Despite its importance, there is a lack of applied research on the range of ethical challenges faced by veterinarians. A three round Policy Delphi with vignette methodology was used to record the diversity of views on ethical challenges faced by veterinary professionals in Ireland. Forty experts, comprising veterinary practitioners, inspectors and nurses, accepted to participate. In round 1, twenty vignettes describing a variety of ethically challenging veterinary scenarios were ranked in terms of ethical acceptability, reputational risk and perceived standards of practice. Round 2 aimed at characterising challenges where future policy development or professional guidance was deemed to be needed. In round 3, possible solutions to key challenges were explored. Results suggest that current rules and regulations are insufficient to ensure best veterinary practices and that a collective approach is needed to harness workable solutions for the identified ethical challenges. Challenges pertaining mostly to the food chain seem to require enforcement measures whereas softer measures that promote professional discretion were preferred to address challenges dealing with veterinary clinical services. These findings can support veterinary representative bodies, advisory committees and regulatory authorities in their decision making, policy and regulation.

Keywords: Veterinary profession, Ireland, Policy Delphi, Ethical Vignettes, Veterinary ethics

Introduction

Ethics is a key determinant of professional conduct in veterinary medicine (Magalhães-Sant'Ana and others 2015). Ethics has been defined as ‘the set of principles or beliefs that governs people's views of right and wrong, good and bad, fair and unfair, just and unjust’ (Rollin 1999, p.11). Despite its importance to the veterinary profession, there has been a lack of applied research on the range of ethical challenges faced by veterinarians and of the extent to which these might affect their professional roles. One account of 58 practising veterinarians in the UK reported that 91 per cent faced at least one ethical dilemma a week (Batchelor and McKeegan 2012).

In dilemmas faced by the profession, there is an increasing awareness of the need to consider the ethical dimension, in order to foster a best-practice approach. Examples include the risks of overprescribing medicines associated with antimicrobials in food animal production and its likely impact on public health (Littmann and Viens 2015), certifying acutely injured animals fit for transport (Cullinane and others 2012), decisions on euthanasia and overtreatment of companion animals (Yeates and Main 2011), and reporting cases of animal abuse and its links with child abuse (Benetato and others 2011).

As part of a wider research project, a web-based Policy Delphi was conducted to explore stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences regarding ethical challenges for veterinary professionals in Ireland. The Policy Delphi is a ‘forum for ideas’, a group facilitation technique structured around several stages and designed to explore the opinion of experts around complex issues (Turoff 1975). Experts included private veterinary practitioners, veterinary inspectors and veterinary nurses working in Ireland.

Contrary to the original Delphi technique, which is aimed at generating group consensus (Hasson and others 2000, Landeta 2006), the Policy Delphi is designed to explore the range of competing views on a given topic (Meskell and others 2014). In this respect, exploring disagreements about a particular topic is as valuable as reaching consensus. Usually, Policy Delphi studies require three to five stages and gather anywhere from 10 to 50 participants under a cloak of quasi anonymity, in which their identity is known only to the researcher (Turoff 1975, Meskell and others 2014).

This technique was used in conjunction with vignettes, which are short stories intended to elicit perceptions, opinions and beliefs (Barter and Renold 1999). Vignettes are especially relevant to bioethics research because they allow potentially sensitive topics to be explored, such as participants’ ethical frameworks and moral views (Barter and Renold 1999, Ulrich and Ratcliffe 2007). Policy Delphi with vignette methodology has been used previously in veterinary medicine to assess stakeholders’ perceptions of equine welfare (Collins and others 2009). The overall aims of this study are to identify significant ethical challenges facing veterinary professionals in Ireland, and explore the roles and responsibilities of Irish veterinary organisations in the implementation of solutions.

Materials and methods

Ethics review

The study conformed to guidelines of the Human Research Ethics Committee at University College Dublin (UCD), permitting exemption from full ethical review (Reference Number: LS-E-14-50). Each participant received a personalised email from MM-S, using Survey Monkey, inviting them to take part in a study on veterinary ethics funded by the Veterinary Council of Ireland. Participants were given the opportunity to be removed from the mailing list and consent was granted by filling a demographic questionnaire. Participants were informed about anonymity, data storage and confidentiality issues (including the use of transcribed extracts). At each round, respondents were given the opportunity to withdraw from the study.

Sample frame

The selection process started with the identification of Irish organisations that represent the range of professional activities performed by veterinary practitioners, veterinary inspectors and veterinary nurses in Ireland. Organisations were identified using snowball sampling (Grbich 1999). Within each organisation, participants were selected to reflect the diversity of the veterinary profession in Ireland. Diversity was sought in terms of age, sex, education, geographical distribution, area of professional activity and experience in policy making. When needed, key informants at each organisation also helped researchers to identify additional participants. In total, 56 individuals (50 veterinarians and 6 veterinary nurses) were identified and invited to be part of the study.

Vignette methodology

Round 1 of the Policy Delphi used 20 practical case scenarios (vignettes; V1–V20) describing ethical challenges in a wide range of veterinary activities, and involving at least one veterinary professional together with other stakeholders (Table 1). The development, construction and validation of the vignettes have been described elsewhere (Magalhães-Sant'Ana and Hanlon 2016). A total of 40 evidence-based vignettes were peer reviewed by academics from the UCD School of Veterinary Medicine including one experienced veterinary nurse, and several veterinarians involved in public health, small animal practice, farm animal practice and equine practice. These experts were also used as the pilot audience for round 1 (n=8), round 2 (n=7) and round 3 (n=6) of the Policy Delphi.

TABLE 1:

Round 1 of the Policy Delphi—the list of 20 vignettes (V) that were used during this round

| Description | Vignette | |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | Working relations (lack of support to recent vet grads) | John runs a mixed practice in Co. Mayo. He is, however, on call most of the time and often leaves a recently graduated vet on his own to run the practice, make consultations and perform surgeries. ‘It's good experience for him. He's fresh out of college and so should know what he's doing!’ |

| V2 | Working relations (between vet colleagues) | Alan receives an anxious phone call from a farmer in Co. Monaghan (not a regular client) to check on a pedigree cow. A colleague from another practice had seen it two days ago and treated it for indigestion. Alan diagnoses torsion and performs surgery only to realise that the necrotic abomasum had caused peritonitis. The animal is euthanased; the owner is furious with the earlier misdiagnosis and is threatening to sue the previous vet. Alan was in college with the other vet and so makes his excuses and leaves. |

| V3 | Work load (vet nurses) | Deirdre, a vet nurse, has been working in small animal practice in Co. Longford for three years. She had a child last year and is again pregnant. During her first pregnancy there were a lot of comments about the inconvenience to the practice and this time she is concerned that she might be replaced by someone else. To avoid being accused of lack of commitment Deirdre has been performing all normal duties, including anaesthesia and diagnostic imaging. |

| V4 | Working relations (between vets and nurses) | In a small animal clinic in Co. Laois, a cat has unexpectedly died during surgery. Aidan, the vet surgeon, instructs a nurse to close the case on his behalf. “Tell the owners that the cat died of anaesthetic complications. And tell them that I am busy with another surgery”. |

| V5 | Professional conduct (use of social media) | Fiona, a small animal nurse in Co. Wicklow, has been treating a Shar-Pei dog with angio-oedema (swollen face). Without the client's consent she posts a picture of the dog on her Facebook wall and writes: “I love Shar-Pei with angioedema!!!!!!!!!! LOLOLOL! They get so… funny!!!” |

| V6 | Small animal euthanasia (suggesting to) | Mary is a small animal vet at a practice in Co. Limerick. An owner comes in with a geriatric Persian cat with signs of chronic kidney failure. Mary advises the owner that the best thing to do is to put the animal down and opts not to discuss other courses of action. ‘The cat has a poor quality of life and at best would only live a few months - there's no point in dragging it out.’ |

| V7 | Small animal euthanasia (refusal of) | Sile runs a small animal clinic in Co. Galway. Someone from a local animal rescue has brought in a dog with severe dermatitis caused by generalised demodicosis (mange). The rescue centre is full and due to the cost of treatment and risk of contagion the charity requests that the dog is euthanased. The rescue worker tries to convince Sile ‘In an ideal world I would opt for treatment, but the resources required for this animal is equivalent to rescuing two or three others’ but Sile refuses the request on moral grounds ‘this animal deserves a chance’, she says. |

| V8 | Provision of 24 hours/emergency service | Emma runs a small animal clinic in Co. Dublin. Podge, a cat with mega colon has been admitted for surgery. The owner is upset about leaving Podge and Emma reassures her, explaining that all pets are provided with ‘overnight care’ (e.g. automatic infusion pump, water or food). Emma omits to say, however, that animals are generally left unattended during the night, from 22:00 (time of the last medication) until 8:00. |

| V9 | Pet blood bank (advanced treatments in small animal medicine) | Miriam, a veterinary haematologist in Co. Offaly, established the first pet blood bank in Ireland and she is selling blood products to private veterinary practices. She was able to attract hundreds of donors by offering routine check-ups and vaccinations in return. ‘By providing a ready supply of blood to practitioners around the country we can save thousands of animal lives and the donors and their owners get a fair deal in return’. |

| V10 | Prophylactic use of antimicrobials (cattle) | Joan routinely prescribes broad-spectrum antibiotics (injectable and tubes) to a dairy farmer with a large herd of 300 animals in Co. Cork. The herd has a low record of somatic cell count (<100,000 cells/ml). Every dry cow gets a tube and most cows are injected. “The preventive use of antibiotics has made this farm one of the best in Ireland—at the end that's good for the animals, and cheaper for the farmer”. |

| V11 | Excessive use of antimicrobials (small animals) | Randal is a mixed practice vet in Co. Waterford. He has been using a range of broad-spectrum antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate, cephalosporins, marbofloxacin) to treat a case of dermatitis in a dog for the previous few months but with no success. The client is not at all happy and has been questioning Randal's treatment based on what he has read on the internet. Following pressure from the client, he agrees as requested to prescribe vancomycin, a drug of last resort used in human medicine. |

| V12 | Medicines (prescriptions and certificates) | Kieran, an equine vet, is called to see a 10-year-old horse with acute laminitis at the premises of a large horse dealer in Co. Leitrim. He injects the horse with bute but the passport is not available at that time to identify the horse as unfit for human consumption. Despite repeated attempts, Kieran fails to obtain the passport and eventually gives up. “The animal will probably be exported and there is no way of linking the treatment for the horse to me”. |

| V13 | Food safety (mislabelling of beef) | Seamus is a veterinary inspector working at a meat plant in Co. Cavan. He is dealing with a case of mislabelling in beef meat (culled cow meat being used in place of prime heifer meat). He reports to the superintendent veterinary inspector who instructs him to keep it quiet. “The last thing we need is another public outcry. The Irish meat industry has gone through enough scandals”. Seamus is no whistle-blower and keeps it quiet. |

| V14 | Unregulated events (equine) | Pat is an equine vet in Co. Kerry. He has volunteered to be a steward at an unlicensed sulky race meeting that regularly takes place in his community. Although he often witnesses mistreatment of horses he has never filed a complaint: “You have to choose your battles - my involvement has helped to improve the routine care and husbandry of the horses”. |

| V15 | Convenience euthanasia (equine) | Andrea runs an equine practice in Co. Kildare. A local breeder makes a living by renting lactating Irish draught mares to be used as wet nurses for thoroughbred foals during the breeding season. Andrea routinely euthanases the surplus foals of these mares, as this is the most convenient and cost-effective option. |

| V16 | Delegation of anaesthesia to farmers (cattle) | Peter is a farm animal vet in Co. Westmeath. He regularly provides local anaesthetic (procaine) to a dairy farmer for use in disbudding calves. ‘I taught him how to use the local anaesthetic and am sure that he is competent. Everyone wins, including the calf’. |

| V17 | Animal welfare in transport and slaughter (cattle) | Charlie works as a temporary veterinary inspector at a local slaughterhouse in Co. Clare. While on ante mortem inspection duty, a cull cow arrives with a broken pelvis and he turns a blind eye, “it would be worse to turn her away and isn't she just about to be put out of her misery anyway?” |

| V18 | Farmer-vet interactions (involving animal welfare) | Karen works in mixed practice in Co. Westmeath. She is doing a routine tuberculosis test and notices that some animals are in extremely poor condition. She knows that the farmer is an alcoholic and has to care for his elderly parents. She decides not to contact the District Veterinary Officer as this could jeopardise his livelihood and push him over the edge. ‘It's a balancing act: you have duties towards the animals; but you also have duties towards fellow human beings.’ |

| V19 | Clinical research and education (vet students) | Kelly is in the middle of her Masters in Veterinary Medicine, and has almost finished her data collection. She is exhausted after the 24 hours serial blood sampling in cattle, only to realise that she lost track of the labelling of the last few samples. To avoid criticism from her supervisor (and repeat sampling), Kelly tries to guess the correct labelling and keeps the incident to herself. “We all make mistakes and I'm exhausted… I couldn't face putting myself or the animals through this again”. |

| V20 | Continuing veterinary education (vets) | Tom has heard from a friend that there is a technical glitch with an online continuing veterinary education module—clicking on the assessment tab automatically generates the certificate of Continuing Veterinary Education (CVE). “Sure what's the problem, CVE is a box ticking exercise – that's me finished for this year!” |

Policy Delphi methodology

Three interconnected rounds were used in the study: round 1 was used to identify relevant ethical challenges for the veterinary professions in Ireland, round 2 sought to characterise these challenges in terms of potential for reputational damage, and possible solutions to key challenges were explored in round 3.

In round 1, vignettes (Table 1) were displayed in random order and participants, using a seven-point Likert scale (1–7), were asked to rank the conduct of the veterinary professional in terms of ethical acceptability regarding those affected by the scenario (1=perfectly acceptable; 7=entirely unacceptable), reputational damage to the broader veterinary profession (1=not at all damaging; 7=very damaging) and perceived standards of practice (1=best practice; 7=malpractice). A not applicable answer (N/A) option was also available. In order to understand whether the three questions were interrelated, the Cronbach's α was calculated for each vignette (Cronbach 1951). At the end of round 1, participants were invited to suggest ethical issues, not covered by the vignettes, which they considered key to the integrity of the veterinary profession.

In round 2, participants were asked to rank (in terms of reputational damage) a number of statements where future policy development or professional guidance was deemed to be needed. Statements originated from both quantitative and qualitative material identified from round 1. These were divided into three key areas: ‘Certification’, ‘Professional Conduct and Working Relations’ and ‘Animal Health and Welfare’ (Table 2). Participants also had the opportunity to describe the rationale for their responses and to include any other issues that might adversely influence the reputation of the veterinary profession.

TABLE 2:

Round 2 of the Policy Delphi—characterisation of key ethical challenges facing the veterinary profession in Ireland, as identified by participants (n=40) during round 1

| Certification | Professional conduct and working relations | Animal health and welfare |

|---|---|---|

| Adequate food safety standards (e.g. to prevent manipulation of meat inspection reports) | Responsible use of social media by veterinary professionals (e.g. to prevent posting a picture of an animal without client's consent). | Performing convenience animal euthanasia (e.g. putting down surplus foals). |

| Responsible disease eradication programmes (e.g. to prevent inappropriately influencing the interpretation of a tuberculosis test result) | Working relationships between veterinarians and veterinary nurses (e.g. nurse being asked to do something that conflicts with his/her ethical values). | The provision of 24 hours and emergency veterinary care (e.g. to prevent lack of adequate overnight care). |

| Responsible casualty slaughter certification (e.g. to prevent incorrectly certifying an animal as being fit for transport) | Guidance on referrals and second opinions (e.g. to prevent failing to refer an animal to another colleague). | Prudent prescription and administration of veterinary medicines (e.g. to prevent excessive use of antibiotics). |

| Responsible veterinary exports certification (e.g. to prevent certifying a herd with an unknown disease status) | Guidance on continuing veterinary education (e.g. to prevent asking for the certificate from a seminar you paid for but didn't attend). | The role of veterinary professionals in unregulated animal fairs, races and shows (e.g. to prevent failing to report abuse to animals). |

| Responsible animal insurance schemes (e.g. to prevent client pressure to change vaccination date) | Responsible clinical research and teaching involving animals (e.g. vet students taking samples from owned animals for their Master of Veterinary Medicine). | Responsible advanced treatments in small animal medicine (e.g. pet cloning or cat kidney transplants). |

The third and final round of the study was used to explore workable solutions for the six key ethical challenges that emerged from the previous rounds (Table 3). These included (a) identifying the Irish organisations (from a list of eight) that should contribute to addressing those challenges, (b) determining whether a single organisation should take primary responsibility or if a collective approach is needed, (c) clarifying possible solutions (from a list of seven) to address each of these challenges, and (d) selecting the solution most likely to effect change.

TABLE 3:

Round 3 of the Policy Delphi—the six key ethical challenges facing the veterinary profession in Ireland (consolidated from rounds 1 and 2) that were used by participants (n=39) to explore workable solutions and identify Irish organisations with responsibility to address them

| Certification | Professional conduct and working relations | Animal health and welfare |

|---|---|---|

| Food safety standards | Referrals and second opinions | Prescription and administration of veterinary medicines |

| Casualty slaughter certification | Working relationships between vets and nurses | 24 hours/emergency care |

Data handling and analysis

For the quantitative material, Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used for data handling and descriptive statistics. Inferential statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics V.20 (IBM Corporation 2011). In terms of qualitative material, thematic analysis was conducted using NVIVO 10 (QSR International 2013), using the data immersion/reduction technique proposed by Forman and Damschroder (2008). Guided by the research questions, a preliminary list of themes was generated after the initial coding of round 1, run by the first author (MM-S) and discussed with coauthors. The list of themes was refined on an ongoing basis as coding progressed through the three rounds. The process was repeated iteratively until a final agreement was reached.

Results

Demographics and response rate

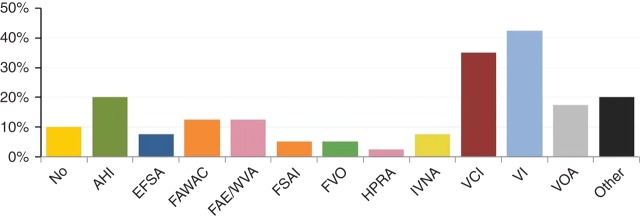

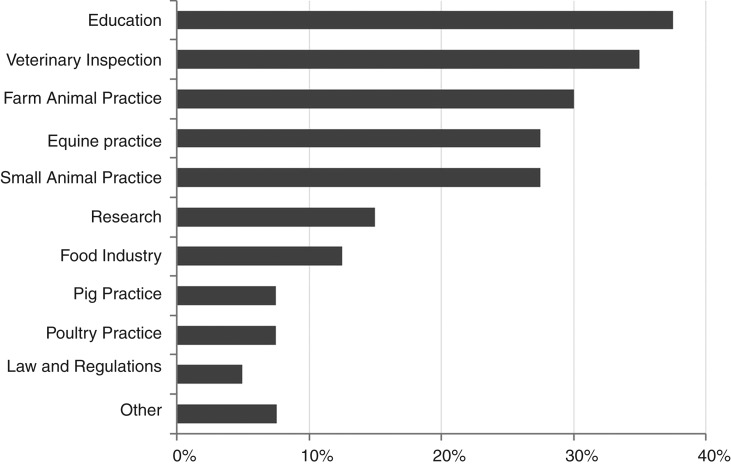

In total, 40 of 56 (71 per cent) experts agreed to participate, including 23 men and 17 women, and 37 veterinarians and 3 veterinary nurses. Four age groups were represented: 26–35 years (5 per cent, n=2); 36–45 years (32.5 per cent; n=13); 46–55 years (32.5 per cent; n=13) and 56–65 years (30.0 per cent; n=12), and three levels of education were present: bachelor's degree (35 per cent; n=14), master’s degree (37.5 per cent; n=15) and doctorate degree (27.5 per cent; n=11). Most participants had experience in policy making with relevant representative and regulatory veterinary bodies, both in Ireland and abroad (Fig 1). Participants’ working location covered all counties in the Republic of Ireland (with predominance of County Dublin (57.5 per cent; n=23)) and Northern Ireland. Ten main areas of professional activity were identified, including small animal practice, equine practice, farm animal practice, veterinary inspection and education, each representing >25 per cent of participants (Fig 2). The Policy Delphi was conducted over a six-month period, between June and December 2014, with response rates of 100 per cent (40/40) in round 1, and 98 per cent (39/40) in rounds 2 and 3.

Fig 1:

Participants’ experience in veterinary policy making. No, no experience; AHI, Animal Health Ireland; EFSA, European Food Safety Authority; FAWAC, Farm Animal Welfare Advisory Council; FVE/WVA, Federation of Veterinarians of Europe/World Veterinary Association; FSAI, Food Safety Authority of Ireland; FVO, Food and Veterinary Office; HPRA, Health Products Regulatory Authority; IVNA, Irish Veterinary Nursing Association; VCI, Veterinary Council of Ireland; VI, Veterinary Ireland; VOA, Veterinary Officers Association

Fig 2:

Policy Delphi participants’ areas of professional activity. Twenty-one participants (52.5 per cent) selected more than one area

Round 1

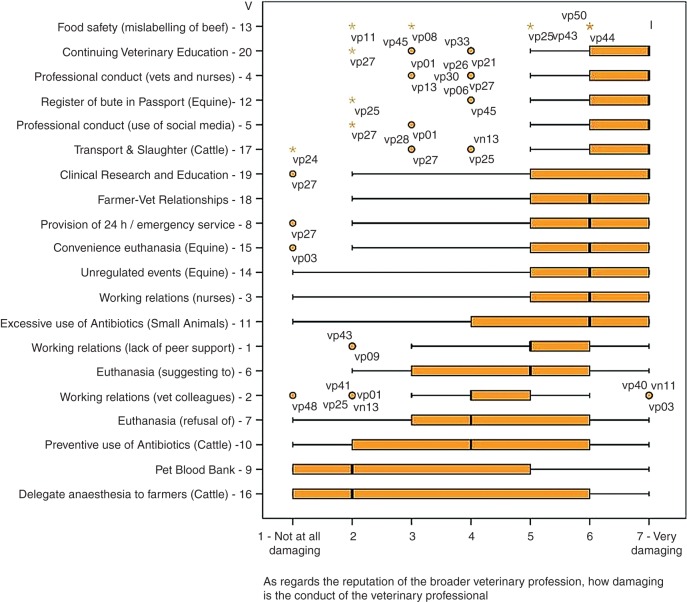

When ranking the conduct of the veterinary professional depicted in the vignettes, the responses of participants to the three questions were similar. The Cronbach's α correlation coefficient ranged from 0.626 to 0.975 (median 0.926) indicating no statistical difference between the moral obligations towards different stakeholders, the reputational damage to the veterinary profession or the perceived standards of practice. Based on the assumption that the three questions each reliably measured the ethical conduct of the veterinary professional, results from round 1 were ordered by potential reputational damage to the veterinary profession (Fig 3).

Fig 3:

Box plot diagram with results as regards the reputation of the veterinary profession (orange boxes indicate the second and the third quartiles; bold bars denote the median; whiskers indicate the 5th and 95th centiles; dots and stars denote outliers and extreme scores, identified by respondents’ Personal Identification number (PIN)). The number of the vignette (V) and a brief description (e.g. Food safety (mislabelling of beef)) is provided. Three participants represented 40 per cent of outlier/extreme responses (vn13, vp25, vp27)

Two-thirds of the case scenarios were considered damaging or very damaging to the reputation of the veterinary profession (Fig 3). There was considerable diversity of views among respondents, particularly among those scenarios considered least damaging, for example, the delegation of animal anaesthesia to farmers (V16), pet blood banks (V9) and the prophylactic use of antibiotics in cattle (V10).

Sixty per cent of participants (n=24) provided written comments. Issues of certification, such as for cattle exports, emerged as prominent ethical challenges faced by veterinarians. Concerns with certification also included casualty animals, tuberculosis screening tests, vaccinations, prepurchase examinations and insurance coverage. Other ethical issues included interprofessional relationships, especially those between nurses and practitioners, financial issues and end-of-life issues.

Round 2

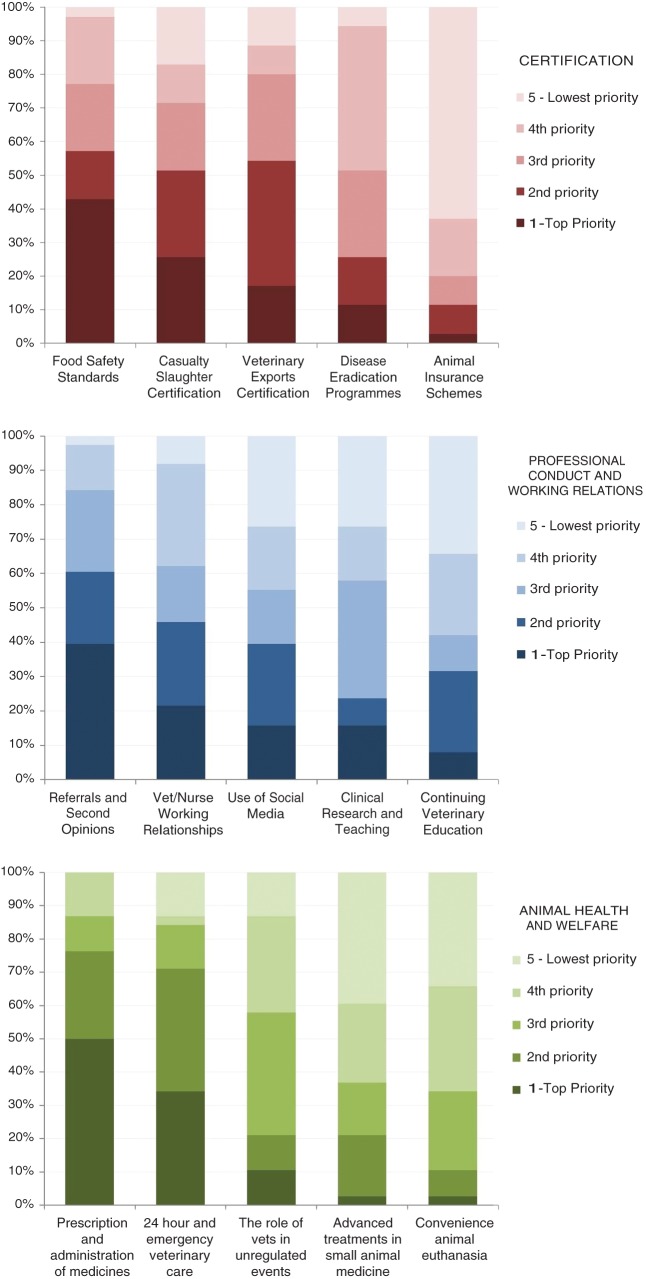

Results from the three areas presented in round 2 (‘Certification’, ‘Professional Conduct and Working Relations’ and ‘Animal Health and Welfare’) will be described separately.

In terms of Certification (Fig 4), three subjects were given high priority for policy development or professional guidance, and assigned either first or second priority by over 50 per cent of participants: ‘food safety standards’, ‘casualty slaughter certification’ and ‘veterinary exports certification’. Strong personal views emerged concerning the risk of damaging the reputation of the veterinary profession. In this regard, one participant stated that:

any false certification by a vet renders, in my mind, that vet unfit to be a member of my profession. Crossing the line of colluding with an animal owner to falsify records or results is just about the worst thing any vet can do and it tarnishes the whole of our profession. (vp28)

Fig 4:

Order of priority (1—top priority; 5—lowest priority) in terms of policy development or professional guidance for five veterinary ethical challenges on ‘Certification’, ‘Professional Conduct and Working Relations’ and ‘Animal Health and Welfare’ presented on round 2 of Policy Delphi

Participants used three main justifications for their ranking: public health (mostly for ‘food safety standards’), animal welfare (mostly for ‘casualty slaughter certification’) and economic issues (mostly for ‘veterinary exports certification’). Most participants prioritised public health concerns over animal welfare, which is also reflected by ranking ‘food safety standards’ over ‘casualty slaughter certification’ (42.9 per cent and 25.7 per cent top priority, respectively). A number of respondents expressed the view that they were not comfortable with having to rank areas that they thought were equally important (although only four used the N/A option).

In regard to Professional Conduct and Working Relations (Fig 4), ‘referrals and second opinions’ was the highest ranked subject (assigned either first or second priority by over 60 per cent of participants). Participants alluded to a ‘continuing problem’ (vp45) where Irish private veterinary practitioners often ignore referral guidelines and were reluctant to seek help from a colleague at the detriment of animal welfare.

Too often in the past in Ireland, clinical cases have not been managed in the primary interest of the animal - there is a temptation to bury one's mistakes [and] not refer them for sorting! The guidance exists, what we need is a cultural shift, away from the blame-game. (vp23)

This seems to be linked to a culture of thinking that ‘I did my best’ (vp24), which might undermine the public's trust in the veterinary profession (vp13). A nurse participant made the plea that “we must stop being afraid to refer on patients that we are not able to treat competently” (vn16).

‘Working relationships between vets and nurses’ was the second highest ranked subject (assigned either first or second priority by over 46 per cent of participants). Two main challenges emerged from the written comments. One challenge concerns the nurse being asked to support poor professional practice by a higher ranked member of staff, and the other refers to assigning nurses with duties or tasks for which they are not competent, according to the Consolidated Veterinary Practice Act (Statutory Instrument No. 22 of 2005).

Regarding Animal Health and Welfare (Fig 4), two highest priority subjects emerged, assigned either first or second priority by more than 70 per cent of participants: ‘prescription and administration of veterinary medicines’ and ‘24 h/emergency care’. In the case of medicines, the responsible use of antibiotics was identified as “the single most important issue facing the profession at present” (vp25) and deficiencies in design and enforcement of legislation were highlighted. One participant stated how difficult it is ‘for intensive livestock vets to be able to describe units as being ‘under their care’ and therefore able to write prescriptions for high powered antibiotics on the basis of just a single visit per year’ (vp19). The concern was expressed that ‘the wider community is becoming aware of the increasing resistance to antibiotics and may point the finger of blame to the veterinary profession for over prescribing’ (vp11).

Provision of 24 hours emergency care was described both as a ‘duty’ and a ‘legal requirement’. As pointed out by one participant, out of hours services should be ‘transparent’ since there is a disparity between clients’ expectations and the actual standard of care that is often provided (vp05). Finally, other issues suggested by participants with reputational risk for the veterinary professions included low biosecurity standards, especially in farm animal practice, oversupply of veterinary graduates throughout Europe, and the fact that veterinarians with poor professional and clinical competences are allowed to practise.

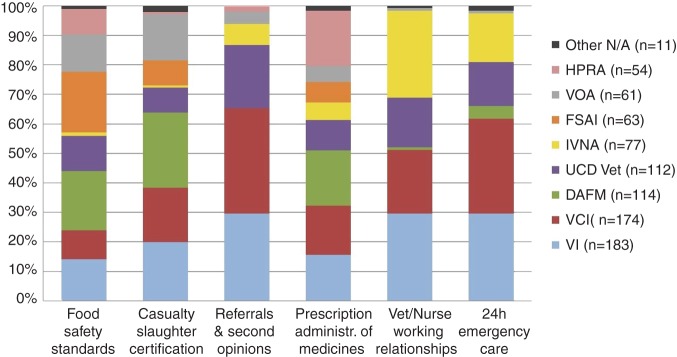

Round 3

When asked which organisations should contribute to addressing the six ethical challenges, there was general agreement that a collective approach is required (Fig 5). Nonetheless, three quarters of participants identified the organisation(s) they thought should take main responsibility, most notably the Food Safety Authority of Ireland (‘food safety standards’), the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM; ‘casualty slaughter certification’), DAFM together with the Health Products Regulatory Authority (‘prescription and administration of veterinary medicines’), Veterinary Council of Ireland (‘referrals and second opinions’, and ‘24 hours emergency care’), and the Irish Veterinary Nurses Association together with Veterinary Ireland (‘vet/nurse working relationships’).

Fig 5:

Percentage (left) and total number (right) of responses as to which organisations should contribute to addressing each of the six ethical challenges presented on round 3 of Policy Delphi. HPRA, Health Products Regulatory Authority; VOA, Veterinary Officers Association; FSAI, Food Safety Authority of Ireland; IVNA, Irish Veterinary Nursing Association; UCD Vet, University College Dublin, School of Veterinary Medicine; DAFM, Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine; VCI, Veterinary Council of Ireland; VI, Veterinary Ireland. N/A, not applicable answer

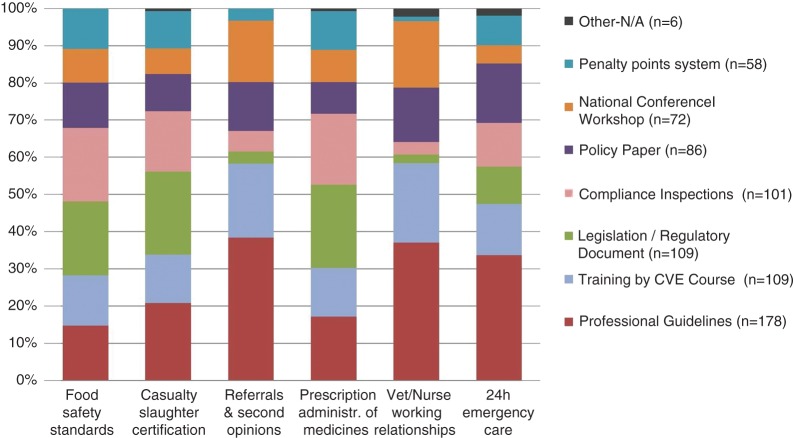

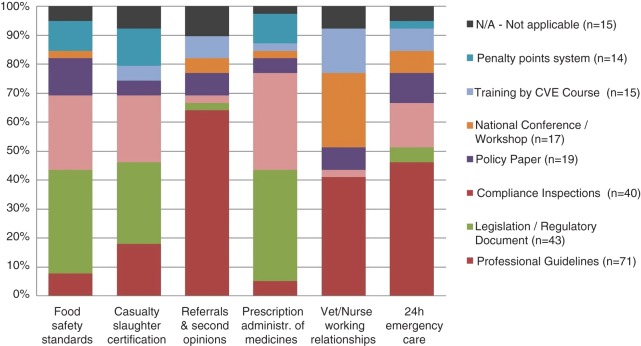

Regarding workable solutions that could be used for addressing the challenges, again a mixed combination of approaches was favoured, with Professional Guidelines being selected more often than other measures (Fig 6). With regard to the measures that are most likely to effect change, there were two broad responses (Fig 7). It was suggested that challenges pertaining mostly to the food chain (‘food safety standards’, ‘casualty slaughter certification’ and ‘prescription and administration of veterinary medicines’) required enforcement measures (i.e. legislation/regulation, compliance inspections and penalty points system). Participants shared the views that ‘legislation is poorly enforced. Compliance needs to be inspected’ (vp31) and that ‘if something is regulated then maybe vets are more likely to comply’ (vp37).

Fig 6:

Percentage (left) and total number (right) of responses as to which solutions can be used to address each of the six ethical challenges presented on round 3 of Policy Delphi. CVE, Continuing Veterinary Education; N/A, not applicable answer

Fig 7:

Percentage (left) and total number (right) of responses as to which solution is most likely to effect change for each of the six ethical challenges presented on round 3 of Policy Delphi. CVE, Continuing Veterinary Education; N/A, not applicable answer

On the other hand, softer measures that promote professional discretion (such as professional guidelines, conferences and Continuing Veterinary Education training) were preferred to address a second group of challenges that deal mainly with veterinary clinical services (‘referrals and second opinions’, ‘vet/nurse working relationships’ and ‘24 hours emergency care’). One participant said: “I don't think we need more legislation, it would be great if what we already have was actually enforced. The vet-nurses relationship would benefit from face to face facilitated meetings to develop a policy that was made widely available. A lot of vets have NO IDEA what nurses are able/trained to do!” (vp45).

Discussion

This study provided an insight into the range of ethical challenges facing veterinary professionals in Ireland. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the most comprehensive attempt to identify the ethical challenges faced by veterinarians anywhere in Europe. It relied on a Policy Delphi technique with vignette methodology to record the diversity of views within the different branches of the Irish veterinary profession, including private veterinary practitioners, veterinary officers, veterinary nurses, inspectors, regulators, scientists and educators.

This study identified three overarching areas where ethical issues may arise: ‘Certification’, ‘Professional Conduct and Working Relations’ and ‘Animal Health and Welfare’. A clear dichotomy emerged regarding the approaches that most likely can effect change (Fig 7), varying between enforcement measures (food chain) and softer recommendations such as professional guidelines (veterinary clinical services). Indeed, enforcement measures have been suggested to deal with poor performance within farm assurance schemes (Main and Mullan 2012). Conversely, regarding veterinary clinical services, Block and Ross (2006) describe the conclusions from a US veterinary committee process which provides guidelines for responsible referrals and second opinions “so that communication is enhanced, public trust in the profession is maintained, and the best medical care possible is provided to our patients” (p.1188).

Participants agreed that ethical challenges should be addressed collectively (Fig 5). However, the view that Veterinary Ireland and the Veterinary Council of Ireland should have a leading role in improving some of the previously identified challenges could be a reflection of participants’ involvement in policy making with these two organisations (Fig 1). Therefore, the question remains of who should take responsibility in dealing with the ethical issues hitherto identified and how best to accomplish this.

Regarding round 2, difficulty in ranking the certification scenarios may reflect the complexity of this area of activity, covering a wide range of subjects, and involving public health concerns, animal health and welfare, and economic issues. An in-depth investigation of five European Codes of Professional Conduct (including the Irish code) identified Certification as one of veterinarians’ main societal duties (Magalhães-Sant'Ana and others 2015). Despite the profusion of rules and guidelines, veterinarians are still faced with significant practical challenges when issuing certificates, which may hamper appropriate professional conduct. To illustrate this point, in a study of slaughterhouse certificates of emergency and casualty bovines in the Republic of Ireland, three quarters of the animals had locomotory injuries (most commonly fractures) and the transport of these animals represented a significant animal welfare concern (Cullinane and others 2012). The authors suggest that, for most of these animals, on-farm emergency slaughter would have been preferred.

This example also works as a reminder that rules alone are not enough for ensuring ethical conduct. As a way to promote appropriate individual and professional ethical values, veterinarians should be instilled with qualities of character (i.e. virtues), which may help them recognise their role as advocates for animals as well as the societal role of the veterinary profession (Magalhães-Sant'Ana and others 2014). Looking at examples from human medicine, the importance of virtue ethics has been emphasised (Gardiner 2003) and a research report on the role of character and virtues in the medical profession in Britain has recently been published (Arthur and others 2015). In his ‘One Health’ approach to the teaching of human and veterinary medical ethics, Magalhães-Sant'Ana (2015) suggests that virtue ethics can be taught formally through guidance (describing appropriate professional attributes), and informally, using role modelling and mentoring. Moreover, zoocentric philosophical approaches to the treatment of non-human animals that are based on virtues have been suggested (cf. Hanlon and Magalhães-Sant'Ana 2014), and that may work as aid references to ethical decision making in veterinary medicine.

One interesting finding from round 1 was the consistency in the answers for the three ethically relevant questions. The Cronbach's α was higher than 0.8 for 18 of the 20 vignettes (Table 4), which indicates a high level of internal consistency. Besides, considering the fact that only three items were being compared, the remaining two α values (0.688 and 0.626) should be considered as robust (Cortina 1993, Field 2009, p.675). Therefore, the three ethical dimensions (moral obligations, reputational damage and standards of practice) consistently measured the ethical conduct of the veterinary professional for a given case scenario, which provides evidence of the robustness and reliability of the vignette methodology applied in this research. However, internal consistency does not equate to homogeneity and the Cronbach's α should not be used as a measure of unidimensionality (Schmitt 1996). Although results from round 1 were organised around reputational risk (and thereafter used to inform subsequent rounds), moral obligations and standards of practice are still relevant ethical concepts to consider.

TABLE 4:

Measure of reliability (Cronbach's coefficient α) between the three questions for each of the vignettes (V) presented in round 1 of Policy Delphi

| V1 | 0.869 | V6 | 0.930 | V11 | 0.945 | V16 | 0.975 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V2 | 0.926 | V7 | 0.909 | V12 | 0.879 | V17 | 0.948 |

| V3 | 0.688 | V8 | 0.970 | V13 | 0.899 | V18 | 0.946 |

| V4 | 0.808 | V9 | 0.964 | V14 | 0.946 | V19 | 0.835 |

| V5 | 0.626 | V10 | 0.926 | V15 | 0.944 | V20 | 0.812 |

Selection of participants using inclusion and preclusion criteria is a key validation step for a Delphi technique (Millar and others 2007) and for this study prerequisites included sex, age groups, levels of education, geographical distribution, areas of professional activity and experience in policy making, in order to provide meaningful results. The literature recommends a response rate of at least 70 per cent at each round of a Delphi study (Sumsion 1998). This threshold was achieved in all stages of the consultation process and the high retention rate throughout the study indicates engagement with the process. It should be noted that the one participant to opt out (vp36, a female, mixed practice practitioner) did not present a reason for doing so; however, its impact on the robustness of the results seems limited.

Vignettes have been previously used to stimulate reflection on medical professionalism (Bernabeo and others 2013). However, they have rarely been used in the veterinary field to explore stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences (e.g. Collins and others 2009). Wainwright and others (2010) recommend the combination of the Delphi method with the use of vignettes for ‘exploring views and opinions in areas of uncertainty, particularly with regard to decision making’ (p.657). Nevertheless, measures should be taken to ensure that vignettes reflect topical and challenging ethical issues instead of what researchers might find as ethically ‘interesting’. This research relied on vignettes that were inspired by real life scenarios using several resources: a focus group session with veterinarians, traditional national media, social media, and relevant literature on Irish farming and veterinary issues (Magalhães-Sant'Ana and Hanlon 2016). In addition, vignettes were validated by veterinary academics and designed for clarity, timeliness and relevance (Magalhães-Sant'Ana and Hanlon 2016). Moreover, the status of quasi anonymity facilitated an honest and genuine approach from participants. Indeed, strong personal views generated throughout the Policy Delphi process (some of them illustrated in this paper) might not have arisen if participants were discussing them face to face.

Conclusion

Results suggest that current rules and regulations are insufficient to ensure best veterinary practices and that a collective approach is needed to harness workable solutions for the identified ethical challenges. Literature recommends that the Policy Delphi technique should work as a precursor to a committee process. Taken together, results from this research can be particularly relevant for veterinary representative bodies, regulatory authorities and government advisory committees to support decision making, policy and regulation. Further research is needed to develop tools to tackle future ethical challenges facing the veterinary professions. In this regard, the present study was followed by a facilitated research workshop with relevant stakeholders aimed at exploring in further detail some of its prominent findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the veterinary experts who were involved in the development of the vignettes and the pilot rounds, and the 40 experts who agreed to take part in this study. The authors also thank Meta Osborne (MVB, CertESM, MRCVS) for her invaluable contribution to this research, as well as Tracy Clegg and Ricardo Segurado for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Funding: Veterinary Council Educational Trust Newman Fellowship in Veterinary Ethics.

References

- ARTHUR J., KRISTJÁNSSON K., THOMAS H., KOTZEE B., IGNATOWITCZ A. & QIU T. (2015) Virtuous Medical Practice. Research Report The Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham

- BARTER C. & RENOLD E. (1999) The use of vignettes in qualitative research. Social Research Update 25 http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU25.html. Accessed July 24, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- BATCHELOR C. E. M. & MCKEEGAN D. E. F. (2012) Survey of the frequency and perceived stressfulness of ethical dilemmas encountered in UK veterinary practice. Veterinary Record 170, 19–19 10.1136/vr.100262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENETATO M. A., REISMAN R. & MCCOBB E. (2011) The veterinarian's role in animal cruelty cases. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 238, 31–34 10.2460/javma.238.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNABEO E. C., HOLMBOE E. S., ROSS K., CHESLUK B. & GINSBURG S. (2013) The utility of vignettes to stimulate reflection on professionalism: theory and practice. Advances in Health Sciences Education 18, 463–484 10.1007/s10459-012-9384-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLOCK G. & ROSS J. (2006) The relationship between general practitioners and board-certified specialists in veterinary medicine. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 228, 1188–1191 10.2460/javma.228.8.1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS J., HANLON A., MORE S. J., WALL P. G. & DUGGAN V. (2009) Policy Delphi with vignette methodology as a tool to evaluate the perception of equine welfare. The Veterinary Journal 181, 63–69 10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORTINA J. M. (1993) What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology 78, 98–104 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CRONBACH L. J. (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16, 297–334 10.1007/BF02310555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CULLINANE M., O'SULLIVAN E., COLLINS G., COLLINS D. & MORE S. (2012) Veterinary certificates for emergency or casualty slaughter bovine animals in the Republic of Ireland: are the welfare needs of certified animals adequately protected? Animal Welfare 21, 61–67 10.7120/096272812X13353700593563 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FIELD A. (2009) Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics. 3rd edn London: SAGE Publications Ltd [Google Scholar]

- FORMAN J. & DAMSCHRODER L. (2008) Qualitative content analysis. In Advances in Bioethics—Empirical Methods for Bioethics: a primer. Vol 11: Eds JACOBY L. & SIMINOFF L. A.. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; pp 39–62 [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER P. (2003) A virtue ethics approach to moral dilemmas in medicine. Journal of Medical Ethics 29, 297–302 10.1136/jme.29.5.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRBICH C. (1999) Qualitative Research in Health: an Introduction. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- HANLON A. J. & MAGALHÃES-SANT'ANA M. (2014) Zoocentrism. In Encyclopedia of Global Bioethics. Ed TEN HAVE H., Springer International Publishing; 10.1007/978-3-319-05544-2_450-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HASSON F., KEENEY S. & MCKENNA H. (2000) Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32, 1008–1015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANDETA J. (2006) Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 73, 467–482 10.1016/j.techfore.2005.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LITTMANN J. & VIENS A. M. (2015) The ethical significance of antimicrobial Resistance. Public Health Ethics 8, 209–224 10.1093/phe/phv025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGALHÃES-SANT'ANA M. (2015) A theoretical framework for human and veterinary medical ethics education. Advances in Health Sciences Education Published Online First: 15 Dec 2015. doi:10.1007/s10459-015-9658-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGALHÃES-SANT'ANA M. & HANLON A. J. (2016) Straight from the horse's mouth—using vignettes to support student learning in veterinary ethics. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education Published Online First: 13 Jun 2016. doi:10.3138/jvme.0815-137R1 10.3138/jvme.0815-137R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGALHÃES-SANT'ANA M., LASSEN J., MILLAR K. M., SANDØE P. & OLSSON I. A. S. (2014) Examining Why Ethics Is Taught to Veterinary Students: A Qualitative Study of Veterinary Educators’ Perspectives. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 41, 350–357 10.3138/jvme.1113-149R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGALHÃES-SANT'ANA M., MORE S. J., MORTON D. B., OSBORNE M. & HANLON A. (2015) What do European veterinary codes of conduct actually say and mean? A case study approach. Veterinary Record 176, 654 10.1136/vr.103005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAIN D. & MULLAN S. (2012) Economic, education, encouragement and enforcement influences within farm assurance schemes. Animal Welfare 21, 107–111 10.7120/096272812X13345905673881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MESKELL P., MURPHY K., SHAW D. G. & CASEY D. (2014) Insights into the use and complexities of the Policy Delphi technique. Nurse Researcher 21, 32–39 10.7748/nr2014.01.21.3.32.e342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLAR K., THORSTENSEN E., TOMKINS S., MEPHAM B. & KAISER M. (2007) Developing the Ethical Delphi. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 20, 53–63 10.1007/s10806-006-9022-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ROLLIN B. E. (1999) An Introduction to Veterinary Medical Ethics: Theory And Cases. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press [Google Scholar]

- SCHMITT N. (1996) Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment 8, 350–353 10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SUMSION T. (1998) The Delphi Technique: An Adaptive Research Tool. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 61, 153–156 10.1177/030802269806100403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- TUROFF M. (1975) The Policy Delphi. In Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Eds LINSTONE H. A. & TUROFF M.. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, pp 84–100 [Google Scholar]

- ULRICH C. M. & RATCLIFFE S. J. (2007) Hypothetical Vignettes in Empirical Bioethics Research. In Advances in Bioethics—Empirical Methods for Bioethics: a primer. Vol 11 Eds JACOBY L., SIMINOFF L. A.. Oxford, UK: Elsevier, pp 161–181 [Google Scholar]

- WAINWRIGHT P., GALLAGHER A., TOMPSETT H. & ATKINS C. (2010) The use of vignettes within a Delphi exercise: a useful approach in empirical ethics? Journal of Medical Ethics 36, 656–660 10.1136/jme.2010.036616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YEATES J. W. & MAIN D. C. J. (2011) Veterinary opinions on refusing euthanasia: justifications and philosophical frameworks. Veterinary Record 168, 263–263 10.1136/vr.c6352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]