Abstract

Respiratory oxidative burst homolog (RBOH)-mediated reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulate a wide range of biological functions in plants. They play a critical role in the symbiosis between legumes and nitrogen-fixing bacteria or arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi. For instance, overexpression of PvRbohB enhances nodule numbers, but reduces mycorrhizal colonization in Phaseolus vulgaris hairy roots and downregulation has the opposite effect. In the present study, we assessed the effect of both rhizobia and AM fungi on electrolyte leakage in transgenic P. vulgaris roots overexpressing (OE) PvRbohB. We demonstrate that elevated levels of electrolyte leakage in uninoculated PvRbohB-OE transgenic roots were alleviated by either Rhizobium or AM fungi symbiosis, with the latter interaction having the greater effect. These results suggest that symbiont colonization reduces ROS elevated electrolyte leakage in P. vulgaris root cells.

Keywords: arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), cell membrane stability, ion leakage, overexpression, P. vulgaris, RBOH, Rhizobium tropici, ROS

Introduction

NADPH oxidases, designated as respiratory oxidative burst homologs (RBOH) in plants, are close relatives of mammalian gp91phox 1 and are encoded by a multigenic family. RBOHs are key regulators of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and have several functions in plants.2 The role of Rboh-mediated ROS in establishing root symbioses has been recently examined, and it was found that RbohB functions as a positive regulator of Rhizobium infection, but as a negative regulator of AM (arbuscular mycorrhizal) fungi symbiosis in Phaseolus vulgaris.3,4 ROS are normally produced at low levels in cell organelles (such as mitochondria, chloroplasts, and peroxisomes); however, under stress conditions, their production increases dramatically.5 In particular, stresses such as salinity, pathogen attack, drought, heavy metals, hyperthermia, and hypothermia are accompanied by ROS-induced cell death, which leads to leakage of intracellular electrolytes through the plasma membrane in plants.6 Little is known about the role of RBOH-dependent ROS on electrolyte leakage and the effect of root symbionts, such as rhizobia and AM fungi, on such drainage. In the present study, we examined the effect of both rhizobia and AM fungi inoculation on the electrolyte leakage resulting from the elevated ROS levels in P. vulgaris transgenic hairy roots overexpressing (OE) PvRbohB.

Results

Estimation of ROS production in PvRbohB overexpressing transgenic roots

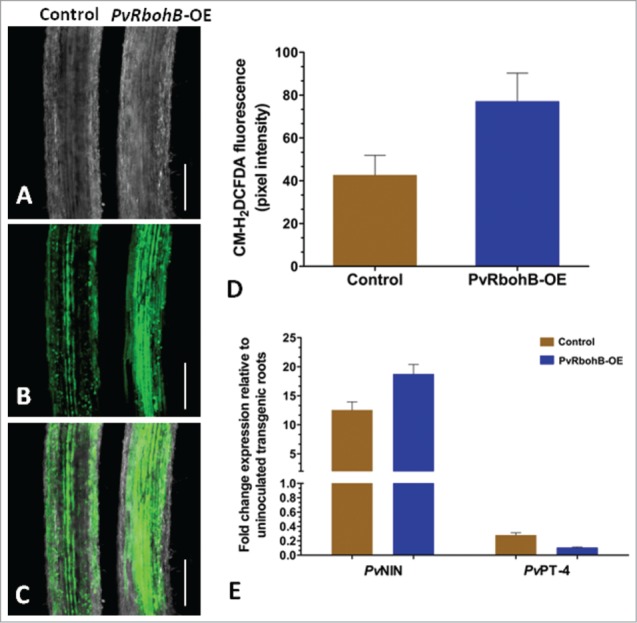

To analyze the effect of PvRbohB overexpression on ROS concentrations, we overexpressed PvRbohB in P. vulgaris composite plants, as described recently.7 Next, we determined whether PvRbohB overexpression increases ROS levels by analyzing uninoculated roots (10 d post emergence; dpe) treated with CM-H2DCFDA.8 The CM-H2DCFDA-treated PvRbohB-OE roots exhibited intense fluorescence, whereas fluorescence was about half as strong in control roots expressing the empty vector (Fig. 1A–C). A comparative analysis of the relative fluorescence intensity in PvRbohB-OE versus control transgenic roots is shown in Figure 1D. These results suggest that increased levels of RbohB transcript result in increased ROS production in transgenic roots.

Figure 1.

Analysis of ROS production in P. vulgaris hairy roots. Transgenic roots expressing empty vector (control) and PvRbohB-OE vector were grown under identical conditions and treated with CM-H2DCFDA to monitor ROS levels. Confocal microscopy images showing similar root zones under (A) transmitted light, (B) fluorescence light, (C) and merged images of A and B. All images were acquired using the image acquisition conditions of the control. (D) ROS level quantification using pixel intensity. The data in the histogram represent the mean ± SD of ROS intensity measured from n > 6 roots. (E) RT-qPCR analysis showing an increase in the expression levels of symbiont-induced PvNIN and PvPT-4 in transgenic hairy roots inoculated with Rhizobium tropici and Rhizophagus irregularis, respectively. Each bar in the histogram represents the mean ± SD (n > 9). Scale bars = 200 µm.

In legumes, the expression of the transcriptional activation factor NIN 9 and phosphate transporter PT-4 10 is induced upon rhizobial and AM fungi inoculation, respectively. In this study, we inoculated PvRbohB-OE and control transgenic roots either with Rhizobium tropici or Rhizophagus irregularis. As shown in Fig. 1E, RT-qPCR analysis of PvRbohB-OE roots shows increased levels of PvNIN in R. tropici-inoculated roots compared to control roots, indicating successful Rhizobium colonization. In R. irregularis-inoculated PvRbohB-OE roots, PvPT-4 transcript was slightly induced, but not significantly compared to mycorrhized controls. Nevertheless, both in PvRbohB-OE and the empty vector controls (control), PvPT-4 transcript was induced in response to successful colonization of AM fungi, as previously shown.7 Furthermore, we found that the nodules of inoculated roots were infected with Rhizobium and arbuscules were present in the mycorrhizal roots (data not shown).

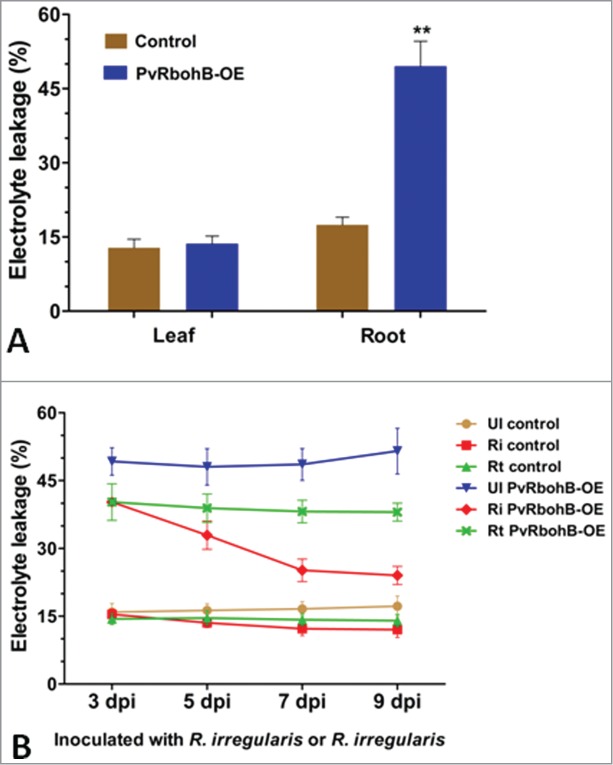

Overexpression of PvRbohB enhances electrolyte leakage in P. vulgaris transgenic roots, whereas symbiont colonization alleviates it

To explore the relationship between overexpression of PvRbohB and electrolyte leakage in uninoculated transgenic roots and to establish whether PvRbohB overexpression in roots alters net electrolyte leakage in leaves, we measured electrolyte leakage in composite plants at 10 d post emergence using the relative conductivity method described by McKay.11 As shown in Fig. 2A, about 49.5 ± 5% of electrolyte leakage was observed in PvRbohB-OE roots compared to 17.5 ± 1.5% in empty vector control roots (that do not overexpress PvRbohB). However, the percentage of electrolyte leakage in the leaves of control and PvRbohB-OE composite plants was the same i.e.,∼ 13% (Fig. 2A). Together, these results suggest that electrolyte leakage is enhanced in transgenic roots that overexpress PvRbohB. We then examined whether inoculation with symbionts (rhizobia or AM fungi) would modify this electrolyte drainage. To do so, we inoculated the transgenic plants with Rhizobium bacteria or with AM fungi and observed the effects on cell membrane stability by measuring electrolyte leakage. Compared to the uninoculated control roots, the percentage of electrolyte leakage in symbiont-inoculated controls decreased by 3.19% and 5.18% in roots colonized with R. tropici and R. irregularis, respectively at 9 dpi (Fig. 2B). Similarly, when PvRbohB-OE roots were inoculated with R. tropici, the change in electrolyte drainage was maximal at 9 dpi i.e., a 13.5% reduction when compared to uninoculated PvRbohB-OE roots (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, when PvRbohB-OE roots were inoculated with R. irregularis, decreased levels of electrolyte leakage were observed when compared to uninoculated PvRbohB-OE roots at all time points. Specifically, a reduction of 23.41% and 27.5% was observed in 7 dpi and 9 dpi roots, respectively, compared to uninoculated PvRbohB-OE roots. In summary, both AM fungi- and Rhizobium-inoculated control roots were better able to reduce electrolyte leakage from the cell membrane upon symbiont inoculation than were uninoculated control roots (Fig. 2B). Together these data suggest that AM fungi colonization overcome the enhanced ROS-induced electrolyte leakage in transgenic roots that overexpress PvRbohB. AM fungi colonization appears to be better than Rhizobium colonization at reducing electrolyte leakage in PvRbohB-OE roots.

Figure 2.

Electrolyte leakage assay in leaves and transgenic hairy roots of P. vulgaris. (A) The assay was conducted using leaf samples of composite plants and transgenic roots at 10 d post emergence. Data are the averages of 2 biological replicates (n > 10). The statistical significance of differences between the control and PvRbohB-OE was determined using an unpaired 2-tailed Student's t-test (*, P < 0.01). Error bars represent means ± SEM. (B) Time course of electrolyte leakage from transgenic roots uninoculated and inoculated with Rhizophagus irregularis or Rhizobium tropici. The plotted values represent the mean ± SD (n > 12). UI, uninoculated; Ri, inoculated with R. irregularis; Rt, inoculated with R. tropici.

Discussion

Electrolyte leakage is ubiquitous among different species, tissues, and cell types, and can be triggered by all major stress factors, including pathogen attack, salinity, heat, wounding, and drought.12 ROS generation frequently accompanies ion leakage in plants subjected to stress. Generally, superoxide production via one electron reduction of triplet oxygen is a starting point for ROS biosynthesis, oxidative stress, and redox regulation in plants.13,14 Expression of NADPH oxidase gene(s), i.e., RBOHs, controls RBOH-dependant ROS production in plants.15 In this respect, our knowledge of the involvement of RBOH-dependant ROS in electrolyte leakage is rudimentary. In this study, we used PvRbohB-OE composite plants to investigate electrolyte leakage under symbiotic and non-symbiotic conditions. First, we determined that overexpression of PvRbohB enhanced ROS production in transgenic roots compared to control roots. Second, we monitored net electrolyte leakage in the uninoculated transgenic roots and leaves of composite plants. Interestingly, we observed that electrolyte leakage significantly increased in the roots of PvRbohB-OE composite plants compared to control roots. Furthermore, the leaves of control and PvRbohB-OE composite plants did not differ in terms of electrolyte leakage, based on the fact that the shoot portion of the composite plants was not transgenic.

Upon rhizobial inoculation, PvNIN expression increased in transgenic roots compared to uninoculated roots.7 Similarly, following R. irregularis inoculation, PvPT-4 expression was induced both in control and PvRbohB-OE plants, indicating successful colonization and phosphate ion uptake by the AM fungi.7 In this study, we observed that elevated levels of electrolyte leakage in uninoculated PvRbohB-OE transgenic roots were alleviated by either AM fungi or Rhizobium symbiosis, and that the effect was greatest upon AM fungi colonization. In Capsicum annuum, mycorrhizal inoculation reduced the damage caused by stress by maintaining the stability of the membrane and the growth of the plant.16 The precise molecular mechanisms mediating symbiont-induced membrane stability under stress conditions remain to be further investigated. Given our results, we propose that AM fungi colonization reduces electrolyte leakage in P. vulgaris root cells, presumably by down-regulating plant cell death.

Methods

Plasmid construction and composite plants

A previously developed overexpression construct, named PvRbohB-OE,7 was used, and the pH7WG2D.1 empty vector was used as a control. The Agrobacterium rhizogenes K599 strain carrying the corresponding constructs was used to generate composite plants in P. vulgaris cv. Negro Jamapa. Transgenic hairy roots were selected based on the fluorescence emitted by green fluorescent protein (GFP; from pH7WG2D.1 vector17) using an epifluorescence SZX7stereo-microscope (Olympus).

Plant growth and ROS determination

Composite plants grown in glass tubes (15 cm) containing B&D media were used to determine ROS concentrations in transgenic roots at 10 d post emergence (dpe). ROS accumulation was assessed in uninoculated transgenic roots using 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes/Invitrogen), according to Duan et al. 8 Images were captured with a Zeiss-LSM/510 confocal laser-scanning microscope using excitation/emission wavelengths of 488-nm/522-nm. ROS-dependent fluorescence levels were quantified by pixel intensity with Adobe Photoshop 5.5 software as described by Park et al.18

Real-Time quantitative PCR analysis

Successful colonization of transgenic bean roots inoculated with R. irregularis or R. tropici was confirmed by 2 methods. First, RT-qPCR analysis of symbiont-inoculated roots was performed as described previously, using the iScriptTM One-step RT-PCR Kit with SYBR® Green, following the manufacturer's instructions, in an iQ5 Multicolor Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Second, symbiont-inoculated roots were visually inspected whether or not the Rhizobium bacteria or the hyphae are present in nodule and AM fungi colonized roots respectively. In order to examine fungal structures, the roots were stained using trypan blue as described by McGonigle et al. 19

Relative electrolyte leakage

Electrolyte leakage was determined using the relative conductivity method in roots11 and leaves20 at 3, 5, 7, and 9 d post inoculation (dpi) with rhizobia or AM fungi. Root material was washed in cold tap water to remove traces of vermiculite and rinsed in deionized water to remove surface ions. Initial conductivity (C0) was measured with a SevenEasy Conductivity Meter (Mettler Toledo, USA) after subjecting the samples to incubation at 25°C in 10 ml de-ionized water overnight with continuous shaking at 100 rpm. The samples were then autoclaved at 110°C for 10 min. Final conductivity (CF) was measured after the samples had cooled to room temperature. The conductivity of de-ionized water was also measured and referred to as Cw. The percentage of electrolyte leakage was calculated as follows: [(C0 − Cw)/(CF − Cw)] × 100.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interests were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rosana Sánchez-López and Dr. Luis Cárdenas (IBT-UNAM) for critically reading the manuscript. We thank QFB Xochitl Alvarado-Affantranger at IBT-UNAM for technical assistance with confocal microscopy and Ing. Ana Lilia Pérez Ramos for performing some experiments. We thank Dr. Mario Rocha (IBT-UNAM) for providing access to the conductivity meter facility.

Funding

This work was supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CB-2010-153718 to C.Q.) with a postdoctoral fellowship (17656) to M.K.A.

References

- 1.Groom QJ, Torres MA, Fordham-Skelton AP, Hammond-Kosack KE, Robinson NJ, Jones JD. rbohA, a rice homologue of the mammalian gp91phox respiratory burst oxidase gene. Plant J 1996; 10:515-22; PMID:8811865; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10030515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sagi M, Fluhr R. Production of reactive oxygen species by plant NADPH oxidases. Plant Physiol 2006; 141:336-40; PMID:16760484; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.106.078089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montiel J, Nava N, Cárdenas L, Sánchez-López R, Arthikala MK, Santana O, Sánchez F, Quinto C. A Phaseolus vulgaris NADPH oxidase gene is required for root infection by Rhizobia. Plant & Cell Physiol 2012; 53:1751-67; PMID:22942250; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/pcp/pcs120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthikala MK, Montıel J, Nava N, Santana O, Sánchez-López R, Cárdenas L, Quinto C. PvRbohB negatively regulates Rhizophagus irregularis colonization in Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant & Cell Physiol 2013; 54:1391-402; PMID:23788647; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/pcp/pct089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz-Lozano JM, Porcel R, Azcón R, Aroca R. Regulation by arbuscular mycorrhizae of the integrated physiological response to salinity in plants: new challenges in physiological and molecular studies. J Exp Bot 2012; 63:4033-44; PMID:22553287; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jxb/ers126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai-Yamada M., Ohori Y., & Uchimiya H (2004) Dessection of Arabidopsis Bax inhibitor-1 suppressing Bax, hydrogen peroxide and salicylic acid-induced cell death. The Plant Cell 16:21-32; PMID:14671021; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1105/tpc.014613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arthikala MK, Sánchez-López R, Nava N, Santana O, Cárdenas L, Quinto C. RbohB, a Phaseolus vulgaris NADPH oxidase gene, enhances symbiosome number, bacteroid size, and nitrogen fixation in nodules and impairs mycorrhizal colonization. New Phytol 2014; 202:886-900; PMID:24571730; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/nph.12714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan Q, Kita D, Li C, Cheung AY, Wu HM. FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:17821-26; PMID:20876100; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1005366107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madsen LH, Tirichine L, Jurkiewicz A, Sullivan JT, Heckmann AB, Bek AS, Ronson CW, James EK, Stougaard J. The molecular network governing nodule organogenesis and infection in the model legume Lotus japonicus. Nat Commun 2010; 1:1-12; PMID:20975674; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda D, Ashida K, Iguchi K, Chechetka SA, Hijikata A, Okusako Y, Deguchi Y, Izui K, Hata S. Knockdown of an arbuscular mycorrhiza-inducible phosphate transporter gene of Lotus japonicus suppresses mutualistic symbiosis. Plant Cell Physiol 2006; 47:807-17; PMID:16774930; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/pcp/pcj069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKay HM. Electrolyte leakage from fine roots of conifer seedlings: a rapid index of plant vitality following cold storage. Can J For Res 1992; 22:1371-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1139/x92-182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demidchik V, Straltsova D, Medvedev SS, Pozhvanov GA, Sokolik A, Yurin V. Stress-induced electrolyte leakage: the role of K+-permeable channels and involvement in programmed cell death and metabolic adjustment. J Exp Bot 2014; 65:1259-70; PMID:24520019; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jxb/eru004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Oxford: Taylor & Francis; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demidchik V. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in plants In: Shabala S, ed. Plant Stress Physiology. Wallingford, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2012; 24-58. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki N, Miller G, Morales J, Shulaev V, Torres MA, Mittler R. Respiratory burst oxidases: the engines of ROS signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2011; 14:691-9; PMID:21862390; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beltrano JM, Ruscitti MC, Arango, Ronco M. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhiza inoculation on plant growth, biological and physiological parameters and mineral nutrition in pepper grown under different salinity and p levels. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr 2013; 13:123-41 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karimi M, Inze D, Depicker A. Gateway vectors for Agrobacterium mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci 2002; 7:193-5; PMID:11992820; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02251-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park KY, Jung JY, Park J, Hwang JU, Kim YW, Hwang I, Lee Y. A role for phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in abscisic acid-induced reactive oxygen species generation in guard cells. Plant Physiol 2003; 132:92-8; PMID:12746515; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.102.016964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGonigle TP, Millers MH, Evans DG, Fairchild GL, Swan JA. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol 1990; 115:495-501; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1990.tb00476.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutts S, Kinet JM, Bouharmont J. NaCl-induced senescence in leaves of rice (Oryza sativa L) cultivars differing in salinity resistance. Ann Bot 1996; 78:389-98; PMID:15535118; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/anbo.1996.013415535118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]