Abstract

Objectives:

Hormonal changes during oral contraceptive pill (OCP) use may affect central corneal thickness (CCT) values. We aimed to evaluate the impact of OCP use on CCT values in healthy young women.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty women subjects who use OCP for contraception (Group 1) and forty control subjects (Group 2) who do not use OCP were included in this prospective study. None of the patients had any history of systemic or ocular diseases. The CCT values measured by ultrasonic pachymeter (Nidek US-4000 Echoscan, Japan) and the intraocular pressure (IOP) values were measured by noncontact tonometer (Reichert 7 CR Corneal Response Technology, USA) at the time of admission to our clinic. The demographic findings and body mass index (BMI) scores of participants were also recorded.

Results:

The mean ages were 32.8 ± 5.6 for OCP + patients (Group 1) and 31.3 ± 6.9 for OCP-patients (Group 2) (P = 0.28). The mean CCT values were significantly higher in Group 1 when compared to that of the Group 2 (540.9 ± 30.4 μm and 519.6 ± 35.6 μm, respectively) (P = 0.003). The mean IOP value was 14.3 ± 2.5 mmHg in Group 1 and 14.4 ± 2.7 mmHg in Group 2 (P = 0.96). The mean BMI scores were 24.4 ± 5.8 kg/m2 in Group 1 and 24.6 ± 3.5 kg/m2 in Group 2 (P = 0.83).

Conclusion:

Our findings revealed that CCT values were significantly higher in patients with OCP use. Ophthalmologists should be aware of potential elevated CCT levels in these patients.

Key words: Central corneal thickness, oral contraceptive pills, young women

Measurement of the central corneal thickness (CCT) is important for the diagnosis and treatment of various ocular conditions such as glaucoma, keratoconus, refractive surgery, monitoring corneal changes after extended contact lens wear.[1,2]

Use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) is common during the reproductive years. Nearly, all women use contraception at some point in their lifetimes. The most common contraceptive method currently being used in women population (approximately, 38% of these women were not currently using contraception) is the OCP (16.0%) in the United States.[3] Gonadotropin hormones may play a role in corneal diseases and CCT may be affected by female hormones.[4] Several studies and case reports have been reported to mention the occurrence of a variety of eye disorders in women using oral contraceptives.[4] However, the effect of ovarian and gonadotropin hormones on corneal biomechanics are unclear. There is no common or absolute information about this subject. We were interested in the association between OCP use and eventual CCT changes in terms of ocular conditions that may be countered.

Body mass index (BMI) is a measure of body fat based on height and weight that applies to adult men and women. Several studies have shown the relation between BMI and ocular and systemic factors.[5,6] Association between higher BMI, thicker cornea and high intraocular pressure (IOP) was mentioned.[5,6] Therefore, we have also calculated and compared the BMI of subjects.

To investigate the possible relationship between CCT and the variation in ovarian and gonadotropin hormones, we aimed to evaluate the changes in CCT levels together with IOP and BMI values in young women during OCP use.

Materials and Methods

We examined fifty young women using OCP for contraception (3 mg drospirenone – 0.03 mg etinil estradiol) who were consecutively referred to our ophthalmology clinic from the family medicine department of our hospital to investigate the affects of OCP use on CCT and also to perform a routine ocular examination. Forty healthy controls without OCP use were also examined. Eligible subjects were required to be either using OCP currently and at least during the previous 3 months (OCP+, Group 1) or not having used any form of hormonal birth control at any period of her life (OCP−, Group 2). All the subjects had no systemic disease in this prospective clinical study. Patients with a period of pregnancy or lactation, at the time of admission to our polyclinic and subjects with obesity to avoid the possible effects on CCT, were excluded from the study. Eyes with a previous history of dry eye, glaucoma, keratitis, uveitis, systemic or topical corticosteroid use, and any ocular surgery or trauma, corneal irregularity such as a corneal scar, dystrophies, microcornea, keratoconus, keratoglobus, contact lens wear, corneal injury, use of topical medication, and high spherical (>−6.0D or >+3D) or cylindrical (>±1.50D) refractive errors were also excluded from the study to avoid the possible affects of these conditions on CCT. All the subjects had regular menstrual cycles lasting between 21 and 35 days. The date of last menstrual periods was noted. BMI scores of patients were also measured to understand whether there was any significant difference between the groups. BMI was calculated based on the formula: BMI = (weight/height2 [kg/m2]). BMI of 19–24.9 kg/m2 were considered as normal.[7]

This study was carried out with the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee approval from Keçioren Training and Research Hospital (791). The research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects after explaining the nature and purpose of the study.

Each subject underwent full ophthalmologic examination including best-corrected Snellen visual acuity, biomicroscopic anterior segment and fundus examination, and corrected IOP measurement by noncontact tonometer (Reichert 7 CR Corneal Response Technology, USA). Three consecutive IOP measurements were taken for each eye, and the mean value was recorded. The ultrasonic pachymeter (Nidek US-4000 Echoscan, Japan) was used to measure CCT. After administering topical proparacaine hydrochloride 0.5% (Alcaine ophthalmic solution, Alcon, Turkey), measurements were taken with the tip of the probe targeting the center of the pupil and perpendicular to the cornea while the subject was looking at a fixed target. The probe was sterilized with alcohol after each subject was examined. At least five consecutive measurements were obtained for each eye, and the mean value was recorded. All CCT and IOP readings were performed by the same experienced physician (Bengi Ece Kurtul) at the same period of the day (10:00 am–12:00 pm) and at the same period of menstrual cycles (luteal phase) of the women. We have noted the date of last menstrual periods of subjects. We could confirm the luteal phase according to ast menstrul period date and gyenecological consultation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS statistical software version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). At the beginning of the study design, we performed power analysis for our study (α = 0.05, power of the test = 0.80). The sample size calculation was ninety patients. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean value ± standard deviation for continuous variables and median and minimum–maximum levels or percentages for categorical variables/string variables. Comparison of continuous values between two groups was performed by means of independent samples t-test. Statistical significance was defined as a P < 0.05.

Results

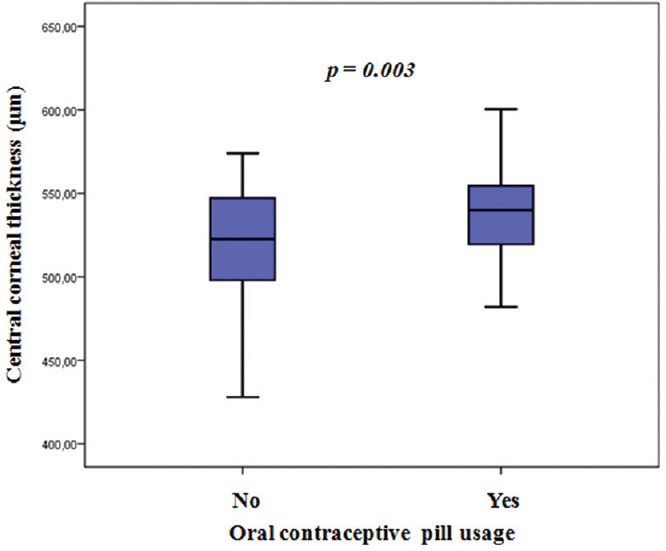

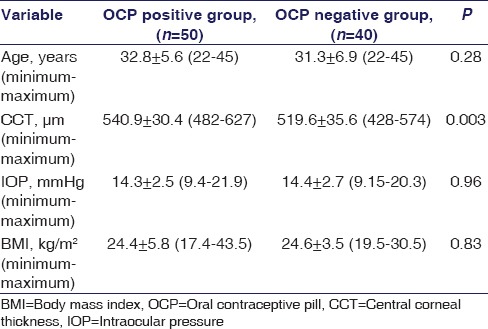

The mean ages were 32.8 ± 5.6 for OCP + patients (Group 1) and 31.3 ± 6.9 for OCP-patients (Group 2) (P = 0.28). The mean duration for OCP use in Group 1 was 26.8 months (3–60 months). The best corrected visual acuities of all patients in both groups were 0.0 Logmar. The mean CCT values were significantly higher in Group 1 when compared to that of the Group 2 (540.9 ± 30.4 μm and 519.6 ± 35.6 μm, respectively) (P = 0.003) [Figure 1]. The mean IOP value was 14.3 ± 2.5 mmHg in Group 1 and 14.4 ± 2.7 mmHg in Group 2. There was no significant difference between the two groups for mean IOP values (P = 0.96). The mean BMI scores were 24.4 ± 5.8 kg/m2 in Group 1 and 24.6 ± 3.5 kg/m2 in Group 2. The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.83). The demographic and clinical parameters are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of central corneal thickness levels between the groups

Table 1.

Demographic features and clinical measurements of study subjects

Discussion

In this study, our findings revealed that CCT values were significantly higher in patients with OCP use.

There is rise in usage of the OCP for contraception in females of reproductive age group and also extended use in regulating the menstrual cycles for the patients. Several studies and case reports were reported to mention the occurrence of a variety of eye disorders such as retinal vascular lesions in women using OCP.[4] Sex hormones appear to influence structural and functional aspects of the anterior and posterior segments of the eye.[4]

CCT and IOP are dynamic parameters. The ocular and systemic factors are known to influence CCT and IOP. In this study, we were interested in the impact of OCP use on these parameters. CCT has a large effect on the measurement of accurate IOP, which is the most important parameter in the diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma. Measurement of the CCT aids the ophthalmologist in making a correct diagnosis for a better management of glaucoma and the glaucoma suspects. Thin CCT and elevated IOP have been proposed as predictive factors for both development as well as the progression of glaucoma.[8]

CCT appears to increase around ovulation and the end of the menstrual cycle, both of which occur after estrogen peaks.[9] Giuffrè G et al.[9] mentioned that the CCT changes during the menstrual cycle as the cornea is thinnest at the beginning of the cycle and thickest at the end. These changes could be secondary to hormonal influences; estrogen receptors can be found in human corneas, suggesting that estrogen may have a role in corneal physiology. In another study, Sony PS had mentioned that the cornea seemed to be thickest either at the beginning or the end of the menstrual cycle because of the variation in ovarian and gonadotropin hormones.[10]

The influence of BMI on IOP has been reported in several studies. BMI had a significant positive correlation with IOP. Stojanov et al.[11] showed obese subjects had significantly higher IOP than subjects with normal weight. Mori et al.[12] found elevated IOP in subjects with BMI over 25 in Japan. Zafra Pérez et al.[13] suggested that elevated IOP is associated with obesity. The association between higher BMI, thicker cornea, and high IOP was also mentioned.[5,6] In this study, BMI scores were not significantly different between groups.

There are also several studies about hormonal changes during pregnancy and its effect on corneal biomechanics. Because of the balanced effect of the various hormones on the cornea during pregnancy, corneal biomechanics may not be changed.[14] In addition, hormone replacement therapy and lifetime estrogen and progesterone exposure do not seem to affect IOP or the risk for increased IOP.[15] In another study, protective role of female hormones was mentioned in women with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG).[16] There are also different hypothesis about IOP in pregnancy. A small fall in IOP occurred with an increase outflow of aqueous from the anterior chamber associated with progesterone in pregnancy.[17] The ciliary processes and aqueous outflow channels are sensitive to hormonal influence.[18] Corneal scleral rigidity decreases according to physiological relaxation during pregnancy; this can be also the cause of the fall in IOP.[19] Efe et al.[20] mentioned that an increase in CCT was accompanied by a decrease in IOP in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

The duration of OCP use is also an important factor for predicting glaucoma. The ≥5 years of OCP use was associated with a modestly increased risk of POAG.[21] The mean duration of OCP use of our subjects was <5 years.

Oral contraceptive use does not appear to increase the risk of eye diseases such as conjunctivitis, keratitis, iritis, lacrimal disease, strabismus, cataract, glaucoma, retinal detachment, with the possible exception of retinal vascular lesions.[2] There is no consistent evidence of a serious increase in risk of eye diseases in patients using OCP.[2] Chen et al.[22] examined the relationship among OCP use, contact lens wear and dry eye signs and symptoms in healthy young women. In their study, tear osmolarity was not affected by OCP. However, OCP usage was found to be a risk factor for retinal vascular occlusion in in-vitro fertilization patients.[23] Orlin et al.[24] have shown bilateral corneal copper deposition secondary to oral contraceptive use. Hormonal changes occurring regularly during gestation may also have a severe impact on the progression of keratoconus. However, these changes are transient and fully reversible.

Study Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we have taken the measurements of subjects at the same time of the day, but we could not evaluate the effect of circadian 24-h CCT rhythm on IOP. Second, relative estrogen and progesterone levels were based on normal menstrual cycle physiology; we have not performed serum hormone testing to confirm levels. Third, measurements were taken at the luteal phase of patients. We could not have the chance to compare the values between follicular and luteal phases. It may be the subject of another study.

Conclusion

The possible variation of corneal thickness values seen among young women can be hypothesized to be related to the ovarian and gonadotropin hormones. By the current study, we propose that CCT measurement should be a constituent part of the ocular examination in women with OCP use, especially during IOP measurements when planning refractive surgery and contact lens wear or for glaucoma and keratoconus monitoring. Therefore, ophthalmologists should be aware of the potentially elevated CCT levels in patients using OCP.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wong AC, Wong CC, Yuen NS, Hui SP. Correlational study of central corneal thickness measurements on Hong Kong Chinese using optical coherence tomography, Orbscan and ultrasound pachymetry. Eye (Lond) 2002;16:715–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ondas O, Keles S. Central corneal thickness in patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1687–90. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-44: United States, 2011-2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;173:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vessey MP, Hannaford P, Mant J, Painter R, Frith P, Chappel D. Oral contraception and eye disease: Findings in two large cohort studies. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:538–42. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.5.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawase K, Tomidokoro A, Araie M, Iwase A, Yamamoto T. Tajimi Study Group; Japan Glaucoma Society. Ocular and systemic factors related to intraocular pressure in Japanese adults: The Tajimi study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1175–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.128819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su DH, Wong TY, Foster PJ, Tay WT, Saw SM, Aung T. Central corneal thickness and its associations with ocular and systemic factors: The Singapore Malay Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:709–716.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westhoff CL, Torgal AH, Mayeda ER, Stanczyk FZ, Lerner JP, Benn EK, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 Pt 1):275–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e79440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Dong L, Yang Z. EMGT Group. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1965–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giuffrè G, Di Rosa L, Fiorino F, Bubella DM, Lodato G. Variations in central corneal thickness during the menstrual cycle in women. Cornea. 2007;26:144–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000244873.08127.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soni PS. Effects of oral contraceptive steroids on the thickness of human cornea. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1980;57:825–34. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stojanov O, Stokic E, Sveljo O, Naumovic N. The influence of retrobulbar adipose tissue volume upon intraocular pressure in obesity. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:469–76. doi: 10.2298/vsp1305469s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori K, Ando F, Nomura H, Sato Y, Shimokata H. Relationship between intraocular pressure and obesity in Japan. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:661–6. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zafra Pérez JJ, Villegas Pérez MP, Canteras Jordana M, Miralles De Imperial J. Intraocular pressure and prevalence of occult glaucoma in a village of Murcia. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2000;75:171–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sen E, Onaran Y, Nalcacioglu-Yuksekkaya P, Elgin U, Ozturk F. Corneal biomechanical parameters during pregnancy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014;24:314–9. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abramov Y, Borik S, Yahalom C, Fatum M, Avgil G, Brzezinski A, et al. Does postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy affect intraocular pressure? J Glaucoma. 2005;14:271–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000169390.17427.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong SY, Si YB, Zhang YY, Zhao GM. Risk factors analysis of primary open angle glaucoma in women. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2013;49:122–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paterson GD, Miller SJ. Hormonal influence in simple glaucoma. A preliminary report. Br J Ophthalmol. 1963;47:129–37. doi: 10.1136/bjo.47.3.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kass MA, Sears ML. Hormonal regulation of intraocular pressure. Surv Ophthalmol. 1977;22:153–76. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(77)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips CI, Gore SM. Ocular hypotensive effect of late pregnancy with and without high blood pressure. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:117–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.69.2.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Efe YK, Ugurbas SC, Alpay A, Ugurbas SH. The course of corneal and intraocular pressure changes during pregnancy. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47:150–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasquale LR, Kang JH. Female reproductive factors and primary open-angle glaucoma in the Nurses' Health Study. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:633–41. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen SP, Massaro-Giordano G, Pistilli M, Schreiber CA, Bunya VY. Tear osmolarity and dry eye symptoms in women using oral contraception and contact lenses. Cornea. 2013;32:423–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182662390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal RS, Mishra VV, Aggarwal SV. Oral contraceptive pills: A risk factor for retinal vascular occlusion in in-vitro fertilization patients. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2013;6:79–81. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.112389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orlin A, Orlin SE, Makar GA, Bunya VY. Presumed corneal copper deposition and oral contraceptive use. Cornea. 2010;29:476–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181b53326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]