Abstract

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is becoming an important genome editing tool for crop breeding. Although it has been demonstrated that target mutations can be transmitted to the next generation, their inheritance pattern has not yet been fully elucidated. Here, we describe the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of four different rice genes with the help of online target-design tools. High-frequency mutagenesis and a large percentage of putative biallelic mutations were observed in T0 generations. Nonetheless, our results also indicate that the progeny genotypes of biallelic T0 lines are frequently difficult to predict and that the transmission of mutations largely does not conform to classical genetic laws, which suggests that the mutations in T0 transgenic rice are mainly somatic mutations. Next, we followed the inheritance pattern of T1 plants. Regardless of the presence of the CRISPR/Cas9 transgene, the mutations in T1 lines were stably transmitted to later generations, indicating a standard germline transmission pattern. Off-target effects were also evaluated, and our results indicate that with careful target selection, off-target mutations are rare in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated rice gene editing. Taken together, our results indicate the promising production of inheritable and “transgene clean” targeted genome-modified rice in the T1 generation using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

Creating the desired gene diversity in crop plants is the main goal of basic functional genomic research and molecular breeding in agriculture. Gene editing using engineering nucleases, e.g., zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) and transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN), effectively generates genetic variants at specific sites in plant genomes. These nucleases induce site-specific double-strand breaks (DSBs) that are then repaired, leading to genome modifications via homologous recombination (HR) or random deletion/insertion of a small DNA sequence adjacent to the target by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ). In cooperation with site-specific DSBs, desired genetic elements that are flanked by DNA sequence similarity to the regions of the break point are used to precisely manipulate the target region in genome editing by HR. NHEJ is error-prone and is frequently used to generate deletion/insertion mutations that are likely to cause gene knockout. In plant genome engineering, NHEJ events are more predominant1,2, but several stable HR-mediated gene-targeting methods have been established for applications in which accuracy is required3,4. Recently, a more affordable and easier-to-use gene editing system, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system, has evolved from studies of the prokaryote-specific adaptive immune system. In this system, the endonuclease Cas9 is coupled with a guide RNA complex (or a synthetic single guide RNA, sgRNA), generating an RNA-guide nuclease. The specificity of Cas9-directed DNA double-strand cleavage is defined by Watson-Crick base-pairing of a 20-base-pair (bp) guide sequence on the guide RNA (gRNA) and a protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM, “NGG” motif) immediately downstream of the target region. The engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system has been shown to achieve efficient genome editing in a variety of plants, including Arabidopsis, rice, tobacco, wheat, sorghum, maize, tomato, liverwort, and orange5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Due to its simplicity, rapidness and broad applicability, the CRISPR/Cas9 system is emerging as a powerful tool for various aspects of fundamental studies of plant biology. In addition, the CRISPR/Cas9 system has also been successfully applied to improving traits in crop plants. Through the simultaneous targeting of three copies of a disease resistance locus in the hexaploid genome, a trait for resistance to powdery mildew was artificially created in bread wheat using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing20. Recent work in our laboratory has also demonstrated that an herbicide resistance trait could be rapidly modified in rice through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing21.

Although successful applications of CRISPR/Cas9 to site-specific plant genome editing are accumulating, most data have been collected from transient assays or the first generation of stable transgenic events. Indeed, there are limited studies indicating that the targeted genome modification created by CRISPR/Cas9 can be transmitted in Arabidopsis, tobacco, tomato and rice5,7,17,22,23,24,25,26,27. In Arabidopsis, most mutations in early generations are somatic mutations, leading to difficulty in predetermining the targeted genotype in the next generation23,25,28. In contrast, most putative homozygous mutations generated in rice by a similar CRISPR/Cas9 system have been suggested to be germline mutations, which can be transmitted according to classical inheritance laws26. Because the editing achieved might vary among different species, target sites, transgene methods and constructions of the CRISPR/Cas9 complex, the transmission patterns that occur still require further exploration in crops. In addition, although inheritance patterns have been intensively examined in later Arabidopsis generations (T2 to T3)12,24,25, there are only preliminary data showing the genetic transmission pattern of modifications in later generations (T1 to T2) of rice27. Therefore, it is worth investigating the inheritance of targeted editing in later rice generations in more detail. Off-target effects are another major concern in the application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The 20-bp gRNA sequence determines the specificity of CRISPR/Cas9, and a “seed region” of 6–12 bp immediately upstream of the PAM is most essential for the stringency of target recognition29. Off-target mutations were indeed induced by CRISPR/Cas9 in human cells29,30,31, though the specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 in plants remains unclear. Independent studies using in-depth whole-genome sequencing and large-scale screening suggest that off-target mutations are rare in Arabidopsis, rice and tobacco12,13,17,26. However, a relatively high frequency of off-target mutations was observed while generating the multi-gene knockout of a rice gene family32. Although there are two mismatches in the 20-bp gRNA region, including one mismatch in the potentially conserved “seed region”, off-target mutations still show comparable efficiencies with that of on-target editing32. The careful design of gRNAs has been suggested to be effective in avoiding off-target mutations in animal cases31,33, and several bioinformatic tools have been developed to facilitate sgRNA design in plants34,35,36, though their stability has not been experimentally tested.

In this study, four rice genes were targeted using computationally designed gRNA with the stably transformed CRISPR/Cas9 system. Targeted mutagenesis was examined in T0 and later generations to determine the transmission pattern of the genome editing achieved. Off-target effects were also evaluated. Our results suggest that the inheritable and “transgene clean” targeted genome modification of rice in the T1 generation can be generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

Results

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in T0 transgenic rice

The rice AOX1 family is composed of three members (OsAOX1a, OsAOX1b and OsAOX1c) with high sequence similarity. To introduce individual mutations, we designed specific 20-bp gRNAs with at least a two-base mismatch at potential off-target sites using bioinformatic tools34,35. These gRNAs were inserted into a GATEWAY-based vector system using a rice-codon-optimized Cas9 gene and an OsU3 promoter, as previously reported7. To evaluate the off-target effects of the system, a 20-bp region of a P450 gene, OsBEL, was selected and constructed. This region has similarity to a sequence located ~7 kb upstream of OsBEL, with a one base mismatch 13 bp upstream of the PAM.

Through Agrobacterium-mediated stable transformation in Nipponbare, 8, 7, 12 and 14 independent T0 transgenic events were obtained, carrying constructs targeting OsAOX1a, OsAOX1b, OsAOX1c and OsBEL, respectively. To detect mutations, genomic DNA was isolated from the third leaf from the top of 10-week-old plants. The target regions were analyzed by sequencing the products of the corresponding site-specific genomic PCR and/or further confirmed by sequencing clones of the PCR amplicons. High mutation rates were induced in all tested targets, and more than half of the lines of each transgene carried mutations (Table 1, Supplemental Fig. S1-S4). The highest mutagenesis efficiency was observed at the OsBEL site, in which the target region was modified in 12 lines out of a total of 14 lines (Table 1, Supplemental Fig. S4). To investigate the possible reason for unsuccessful target mutagenesis, the presence of the transgene was determined by amplifying sgRNA, Cas9, and hygromycin phosphotransferase (HPT) in non-mutated lines (designated as WT). Among a total of 12 WT lines, 6 lines lacked detectable Cas9 and/or sgRNA transgene fragments (Supplemental Table S1), implying that a deficiency in the integrity of the sgRNA/Cas9 expression cassette might be a major reason for the failure of targeted mutagenesis. We also tested the numbers of T-DNA insertions in all transgenic lines by determining the copy number of HPT via real-time PCR analysis. Most lines carrying target mutations contained 1–2 copies (Table 1), suggesting that it may be possible to segregate out the transgene.

Table 1. Identification of CRISPR/Cas9-induced target mutations in T0 generations.

| Target Gene | Line# | Genotype* | Zygosity# | Copy Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OsAox1a | 1 | 4d2d5,5d11a | Com-He | 2 |

| 2 | 7d44,3d29 | Com-He | 1 | |

| 3 | 8d11b | Ho | 1 | |

| 4 | 2d3,5d6 | Com-He | 1 | |

| 5 | 9WT | WT | 1 | |

| 6 | WT | WT | 2 | |

| 7 | WT | WT | 1 | |

| 8 | WT | WT | ≥3 | |

| OsAox1b | 1 | 9d2,3d4 | Com-He | 1 |

| 2 | 4d3,4d69 | Com-He | 2 | |

| 3 | 6d1,1d31 | Com-He | 1 | |

| 4 | 9d1,2d4 | Com-He | 1 | |

| 5 | WT | WT | 1 | |

| 6 | WT | WT | 2 | |

| 7 | WT | WT | 1 | |

| OsAox1c | 1 | 8d2 | Ho | 1 |

| 2 | 4d2 | Ho | ≥3 | |

| 3 | 7i1a | Ho | 1 | |

| 4 | 9i1b | Ho | 2 | |

| 5 | 5s1,4WT | He | 2 | |

| 6 | 8i1c,3WT | He | 1 | |

| 7 | 6d10,5WT | He | 1 | |

| 8 | 7i1b,3s1 | Com-He | 1 | |

| 9 | 5d5,3d3 | Com-He | 1 | |

| 10 | WT | WT | 2 | |

| 11 | 6WT | WT | 1 | |

| 12 | WT | WT | ≥3 | |

| OsBEL | 1 | 10d12 | Ho | ≥3 |

| 2 | 11d4 | Ho | 2 | |

| 3 | 9d1 | Ho | 1 | |

| 4 | 12d1 | Ho | 1 | |

| 5 | 5d1,5WT | He | 2 | |

| 6 | 4d6,3WT | He | 2 | |

| 7 | 6d4,6WT | He | 1 | |

| 8 | 2d1,2d2,2d3a,4WT | Ch | 2 | |

| 9 | 3d1,5d2,3WT | Ch | 1 | |

| 10 | 7d1,3i1 | Com-He | 2 | |

| 11 | 8d1,2d4 | Com-He | 2 | |

| 12 | 5d1,5d8 | Com-He | 1 | |

| 13 | WT | WT | 1 | |

| 14 | WT | WT | 1 |

*WT, wild-type sequence with no mutation detected; d#, # of bp deleted from the target site; d#a, the same number of deletions at one site; d#b, the same number of deletions at other sites; s#, # of bp substituted from the target site. i#, # of bp inserted at the target site; i#a, the same number of insertions at one site; i#b, the same number of insertions at other sites; i#c, the same number of insertions at the third site.

#The zygosity of homozygote (Ho), compound heterozygote (Com-He), heterozygote (He) and chimera (Ch) in T0 plants is putative.

Some reports have indicated that 1-bp changes (deletions or insertions) are the main type of mutation induced by stably transformed CRISPR/Cas9 in both Arabidopsis and rice23,26. However, a remarkable abundance of deletions of long fragments (≥ 3 bp) were observed in a study of high-efficiency gene editing targeting rice SWEET1327. We found that the types of mutations varied among target regions. For OsAOX1c and OsBEL, short changes (≤ 3 bp) were the major type of mutation; conversely, all mutations in OsAOX1a were relatively long deletions. Because short deletions are often associated with classical NHEJ (cNHEJ) and longer deletions may represent the results of microhomology-mediated end-joining (or alternative NHEJ, aNHEJ)37,38, the CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutation patterns might be different for specific DSB sites through distinguished NHEJ repair pathway.

The genotypes of the mutants were also analyzed. Consistent with previous reports26,27, putative biallelic i.e., homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations mostly occurred in genotypes in the T0 generation, accounting for 41.4% (12/29) and 31.0% (9/29) of all mutant plants, respectively.

Inheritance and stability of targeted mutagenesis in the T1 generation

To investigate the pattern of transmission of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted gene modification, several T1 progeny were obtained by strict self-pollination and used for testing of targeted mutations. For each T0 line, 8-24 progeny were randomly selected and examined. As shown in Table 2, all of the mutated T0 lines produced mutated T1 progeny, whereas targeted sequence changes still could not be detected in the progeny of WT T0 plants.

Table 2. Segregation patterns of CRISPR/Cas9-transgenic plants during the T0 to T1 generation.

| Line | T0 |

T1Segregation ratio |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Zygosity* | Targeted mutation# | T-DNA$ | |

| OsAOX1a#1 | d2d5,d11a | Com-He | 24d11ad11a | 23+:1− |

| OsAOX1a#2 | d44,d29 | Com-He | 17d44d44 | 13+:4− |

| OsAOX1a#3 | d11bd11b | Ho | 20d11bd11b:3He:1d8d11b | 20+:4− |

| OsAOX1a#4 | d3,d6 | Com-He | 8d6d6: 3d3d6:13He | 15+:9− |

| OsAOX1a#7 | WT | WT | 24WT | 18+:6− |

| OsAOX1b#1 | d2,d4 | Com-He | 13d2d2:7d2d4:4d4d4 | 17+:7− |

| OsAOX1b#2 | d3,d69 | Com-He | 19d69d69 | 16+:3− |

| OsAOX1b#3 | d1,d31 | Com-He | 24d31d31 | 19+:5− |

| OsAOX1b#4 | d1,d4 | Com-He | 2d1d1: 6d1d4:3d4d4 | 8+:3− |

| OsAOX1b#5 | WT | WT | 16WT | 10+:6− |

| OsAOX1b#6 | WT | WT | 18WT | 18+ |

| OsAOX1c#1 | d2d2 | Ho | 5d1d1:3d2d2:14d1d2 | 16+:6− |

| OsAOX1c#3 | i1ai1a | Ho | 6i1ai1a:4He | 7+:3− |

| OsAOX1c#4 | i1bi1b | Ho | 2i1ai1a:3i1bi1b:1i1ci1c:4He:7WT | 16+:1− |

| OsAOX1c#6 | i1c,WT | He | 6i1ci1c:3i1bi1c:5He#1:2He#2:3WT | 13+:6− |

| OsAOX1c#7 | d10,WT | He | 2d10d10:1d10d52:3He#1:3He#2:5WT | 9+:5− |

| OsAOX1c#9 | d5,1d3 | Com-He | 1d5d5:5ch:10He:2WT | 15+:3− |

| OsAOX1c#12 | WT | WT | 19WT | 19+ |

| OsBEL#1 | d12d12 | Ho | 12d12d12 | 12+ |

| OsBEL#2 | d4d4 | Ho | 5d4d4:4d4d1:2d4d25:6He | 13+:4− |

| OsBEL#3 | d1d1 | Ho | 16d1d1 | 15+:1− |

| OsBEL#6 | d6,WT | He | 5d6d6:3He:16WT | 20+:4− |

| OsBEL#7 | d4,WT | He | 7d4d4:2d4d3b:5d1d1:4He:1Ch | 14+:5− |

| OsBEL#8 | d1,d2,d3a,WT | Ch | 2d1d1:5d1s1d1s1:1Ch | 7+:1− |

*The zygosity of homozygote (Ho), compound heterozygote (Com-He), heterozygote (He) and chimera (Ch) in T0 plants is putative.

#The genotypes in the T1 generation were as follows: OsAOX1a#3 He (d11b, WT); OsAOX1a#4 He (d3, WT); OsAOX1c#3 He (i1a, WT); OsAOX1c#4 He (i1b, WT); OsAOX1c#6 He#1 (i1c, WT); OsAOX1c#6 He#2 (i1b, WT); OsAOX1c#7 He#1 (d10, WT); OsAOX1c#7 He#2 (d52, WT); OsAOX1c#9 He (d5, WT); OsAOX1c#9 Ch (d2, d3, d5); OsBEL#2 He (d4, WT); OsBEL#6 He (d6, WT); OsBEL#7 He (d1, WT); OsBEL#7 Ch (d1, d3b, d20); OsBEL#8 Ch (d1, d4, d45, WT).

$+, The number of T-DNA regions that were detected; -, the number of T-DNA regions that were not detected.

Genotypes are thought to be easily predicted in the progeny of biallelic T0 lines26. As expected, all 12 and 16 T1 progeny of homozygous OsBEL #1 and #3, respectively, exhibited consistent homozygous 12-bp or 1-bp deletion genotypes (Table 2). However, we observed that the transmission of targeted mutations was relatively ruleless in large subsets of putative biallelic T0 lines. Three unexpected patterns can be summarized as follows. (1) The mutations occurring in T0 were lost in the T1 generation. OsAOX1a line #1 was determined to be a putative biallelic mutation with 7-bp and 11-bp deletions, whereas only the 11-bp deletion could be detected in T1 plants as a homozygous genotype (Table 2). In OsAOX1a #2 and OsAOX1b #2 and #3, the selective transmission of a single parental allele was also found in the progeny. (2) New mutations were created in the T1 generation (Table 2, Supplemental Fig. S5). For example, the sequencing results indicated a putative homozygous 1-bp insertion genotype in an OsAOX1c #4 T0 plant, whereas 2 additional different 1-bp insertions were found in the T1 population (Table 2). Similarly, a number of additional mutations were detected in the T1 generations of OsAOX1c #9 and OsBEL #2, even though the majority of progeny mutations were already observed in the parental genome. In addition, several putative biallelic mutated T0 lines, e.g., OsAOX1c #3, #9 and OsBEL #2, could generate progeny carrying the WT allele. This result suggested that some cells of the T0 plants might not be target modified in these lines. Meanwhile, these cells were also not detected in the genotyping of T0 plants. (3) The segregation ratio of target mutations in the T1 generation was distorted. A 1:1 ratio of the parental mutated alleles was anticipated in the progeny of biallelic plants, based on regular segregation laws. In the T1 plants of the biallelic mutated OsAOX1b #1 lines, although the mutation types did not increase or decrease, the ratio between the two alleles in the T1 plants did not conform to 1:1, indicating that they were not inherited with equal frequencies.

Because the sgRNA-Cas9 complex has been shown to be active in heterozygous and chimeric plants5,24,26,27, WT alleles are likely to be modified continuously. As expected, a number of new mutations were found in the corresponding T1 lines (e.g., OsAOX1c #6 and #7; OsBEL #7 and #8), whereas most of the mutations detected in the T0 heterozygotes and chimeras were passed on to the next generation (Table 2). Whether or not there was additional mutation of T0 heterozygotes in the T1 generation, the ratio between the parental mutated allele and other alleles should be expected to be 1:1 in the T1 population. However, the frequency of the parental mutation in some T1 generated from T0 heterozygotes, e.g., OsAOX1c #6 and OsBEL #6, was significantly lower than 50% by the chi-square test, suggesting that additional mutations likely occurred in other undetermined parts of the T0 plants.

The presence of the transgene (T-DNA) region was also examined in T1 populations. The absence of the transgene was determined to be concurrent in PCRs negative for Cas9, sgRNA and HPT genes, and the results indicated that the T-DNA region could be segregated out in most lines. Transgene-negative plants were observed in nearly all of the low-copy T0 progeny (Table 2).

Segregation of targeted mutagenesis in T2 generations

As described above, intricate segregation patterns were detected in the T1 generation. To further investigate the inheritance of targeted mutations in later generations, the genotypes of several T2 plants were analyzed in detail. Because the sgRNA/Cas9 complex may still be active in progeny and thus disturb genotype transmission, the segregation of mutations in T-DNA-lacking T1 progenitors was examined first. A total of 12 T1 lines carrying 3 genotypes (8 homozygous, 3 compound heterozygous and 1 heterozygous) and lacking the transgene were selected and analyzed. By sequencing targeted genomic regions of an extensive T2 population derived from T1 homozygotes, all of the descendants were found to exhibit the same homozygous mutations, without exception (Table 3). Similarly, the ratio between the two alleles of the biallelic and heterozygous T1 plants conformed to the expected 1:1 ratio of classical Mendelian segregation by the chi-square test (Table 3). All of these results indicate that, in the absence of the transgene, the inheritance of targeted mutations is stable and regular in later generations. Furthermore, the patterns of transmission from T1 to T2 were examined in the presence of the transgene. For this assay, 4 T-DNA-positive T1 homozygous and 2 compound heterozygous T1 lines were selected, and the genotypes were examined in their progeny. As shown in Table 4, the parental mutations were not modified or revised in the T2 generation, possibly due to the absence of editable targets of CRISPR/Cas9. We also followed 4 T1 heterozygotes to the T2 generation and found that most of the genotypes were inherited normally, with only one additional mutation detected in a single T2 plant (Table 4).

Table 3. Segregation patterns of CRISPR/Cas9 modifications during the T1 to T2 generation in the absence of the transgene region.

| Line | T1 |

T2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Zygosity | T-DNA | Segregation ratio* | T-DNA# | ||

| OsAOX1a #1–3 | d11ad11a | Ho | — | 24d11ad11a | 24— | |

| OsAOX1a #2–2 | d44d44 | Ho | — | 21d44d44 | 21— | |

| OsAOX1a #2–17 | d44d44 | Ho | — | 24d44d44 | 24— | |

| OsAOX1a #3–4 | d11bd11b | Ho | — | 18d11bd11b | 18— | |

| OsAOX1b #1–1 | d4d4 | Ho | — | 20d4d4 | 20— | |

| OsAOX1b #2–9 | d69d69 | Ho | — | 22d69d69 | 22— | |

| OsAOX1b #3–4 | d31d31 | Ho | — | 24d31d31 | 24— | |

| OsAOX1b #4–7 | d1d1 | Ho | — | 20d1d1 | 20— | |

| OsAOX1a #3–8 | d8,d11b | Com-He | — | 5d8d8:13d8d11b:4d11bd11b | 22— | |

| OsAOX1a #4–3 | d3,d6 | Com-He | — | 7d3d3:11d3d6:6d6d6 | 24— | |

| OsAOX1b #4–5 | d1,d4 | Com-He | — | 3d1d1:8d1d4:6d4d4 | 17— | |

| OsAOX1a #4–12 | d3,WT | He | — | 5d3d3:11He:7WT | 23— | |

*The genotype of the

OsAOX1a#4-12 He plant in the T2 generation was (d3, WT).

Table 4. Segregation patterns of CRISPR/Cas9 modifications during the T1 to T2 generation in the presence of the transgene region.

| Line | T1 |

T2 Segregation ratio* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Zygosity | T-DNA | ||

| OsAOX1a #1–1 | d11ad11a | Ho | + | 12d11ad11a |

| OsAOX1a #4–9 | d6d6 | Ho | + | 12d6d6 |

| OsAOX1b #2–3 | d69d69 | Ho | + | 10d69d69 |

| OsAOX1b #4–13 | d1d1 | Ho | + | 12d1d1 |

| OsAOX1a #4–19 | d3d6 | Com-He | + | 2d3d3:5d3d6:3d6d6 |

| OsAOX1b #4–2 | d1d4 | Com-He | + | 1d1d1:8d1d4:3d4d4 |

| OsAOX1a #3–14 | d11b,WT | He | + | 2d11bd11b:7He:3WT |

| OsAOX1a #4–1 | d3,WT | He | + | 1d3d3:5He:1Ch:2WT |

| OsAOX1a #4–2 | d3,WT | He | + | 3d3d3:4He:4WT |

| OsAOX1a #4–18 | d3,WT | He | + | 5d3d3:3He:2WT |

*The genotypes in the T2 generation were as follows: OsAOX1a#3–14 He (d11b, WT); OsAOX1a#4–1 He (d3, WT); OsAOX1a#4–1 Ch (d3, d5, WT); OsAOX1a#4–2 He (d3, WT); OsAOX1a#4–18 He (d3, WT).

Off-target analysis

Based on the predictions of the CRISPR-P tool, we first analyzed the off-target effects of the editing of OsAOX1 genes. The two most likely off-target sites of each target were selected and examined in all of the T0 plants, all of the T-DNA-negative T1 plants generated from mutated T0 lines and 24 randomly selected lines of T-DNA-positive T1 plants with on-target mutation by site-specific genomic PCR based Sanger sequencing. As shown in Table 5, no mutations were found in the putative loci, even though on-target mutations could easily be detected.

Table 5. Detection of mutations on the putative off-target sites.

| Target | Name of putative off-target site | Putative off-target locus | Sequence of the putative off-target site | No. of mismatching bases | *No. of plants sequenced | No. of plants with mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OsAOX1a | OFF1 | Chr6:8886912-8886890 | GAGTCGTGGTCAACAGCTAGGGG | 4 | 50 | 0 |

| OFF2 | Chr6:13427405-13427383 | AGGTGGTGGCCACCAGCTCCTGG | 3 | 50 | 0 | |

| OsAOX1b | OFF3 | Chr8:22659044-22659066 | CAGCGAGGTGAGCTCGCGAAAGG | 3 | 49 | 0 |

| OFF4 | Chr11:6535738-6535715 | CTCAGCGATGAGCTCCTGAAGGG | 4 | 49 | 0 | |

| OsAOX1c | OFF5 | Chr10:20144706-20144728 | GGAGGAGGCGGCCGCGTCCTCGG | 2 | 60 | 0 |

| OFF6 | Chr2:15363651-15363629 | GGCGGAGGCGGCCGCGTCCTGGG | 3 | 60 | 0 | |

| OsBEL | OFF7 | Chr3:31436831-31436853 | GCGAGGTGCGCGCCATGGTGCGG | 1 | 89 | 2 |

| OFF8 | Chr4:23949393-23949415 | GAGAGGTGGGCGCCATGGTGGGG | 3 | 89 | 0 |

The PAM motif (NGG) is marked by a box; mismatching bases are shown in red.

*For targets of OsAOX1a, OsAOX1b and OsAOX1c, all of the T0 plants, all of the T-DNA-negative T1 plants generated from mutated T0 lines, and 24 randomly selected lines of T-DNA-positive T1 plants with on-target mutation were used. For OsBEL targets, all of the T0 plants, all of the T-DNA-negative T1 plants generated from mutated T0 lines, and 60 randomly selected lines of T-DNA-positive T1 plants with on-target mutation were used.

According to previous reports and bioinformatic tools, the editing of OsBEL is very likely to be an off-target event because the selected 20-bp gRNA region is highly homologous (1 bp mismatched outside of the seed region) with the other PAM ended sequence. The targeted site and the putative off-target site are 7 kb apart; therefore, we first examined the large deletion formed by the re-joining of the two cleavage sites. We did not detect a deletion between the two sites by PCR in any of the T0 and T1 generation OsBEL target plants (data not shown). To further evaluate the potential off-target effects of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in rice, we used PCR to amplify a 254-bp region around the putative site and then sequenced that region. It was not changed in any of the T0 and transgene-negative T1 plants. We further examined 60 lines of transgene-positive T1 plants, and mutations were observed at off-target sites in two individual plants derived from different T0 lines (Table 5). These results suggest that in this system, off-target modifications are rare and occur only in the transgene-positive T1 generation.

Discussion

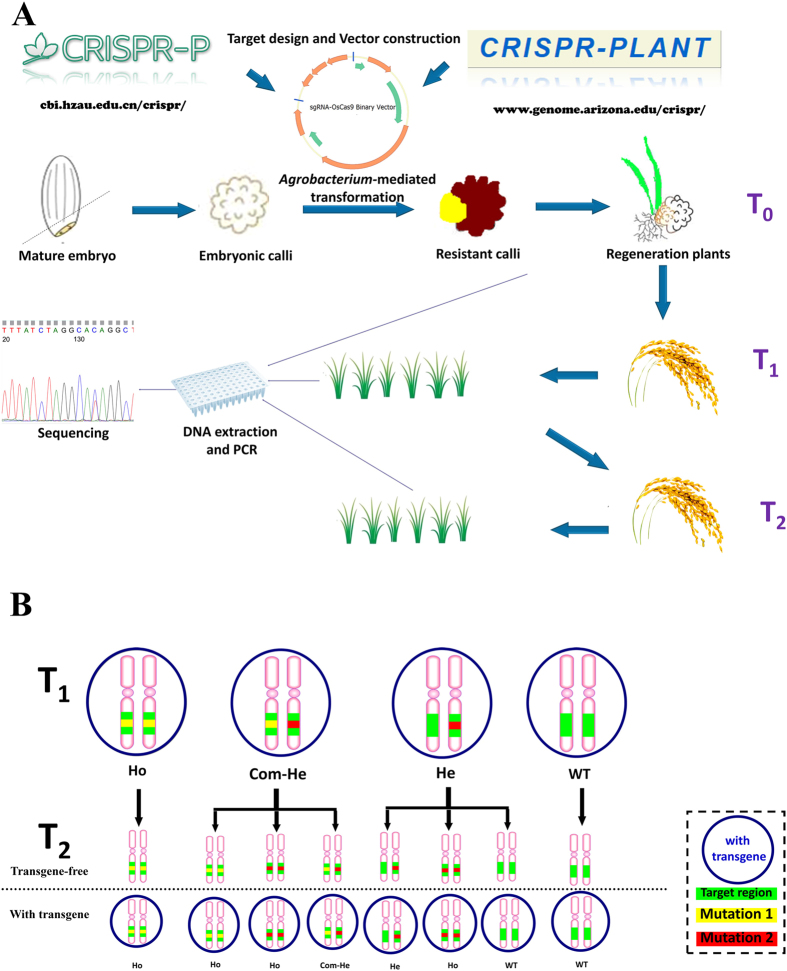

The predictable inheritance and segregation of genome modifications in later generations is highly desired in molecular breeding as well as in basic research. In this study, we targeted four different genes using a previously reported Gateway-based CRISPR/Cas9 system7. The schematic procedure of generation and analysis of targeted mutated plants was described in Fig. 1A. Our results confirm the high efficiency of this system in the T0 generation. We found that a part of the un-mutated lines lacked the sgRNA, the Cas9 cassette, or even both, which is consistent with another rice CRISPR/Cas9 application using a different vector system27. Interestingly, the left border (LB) of T-DNA is easier to truncate during the integration. However, the selectable marker was located closer to LB than the transgene fragments of CRISPR/Cas939. These phenomena suggest that the possible recombination of the T-DNA fragment might be a potential reason to restrict the mutagenesis efficiency. According to the sequencing results for genomic DNA isolated from single leaves, a large percentage of edited T0 generations are biallelically modified. An abundance of biallelic modifications, especially homozygous types, typically indicates that the mutations were generated at a very early developmental stage of the transformed embryogenic cell, suggesting the high possibility of predictable germline transmission26. However, we found that T1 genotypes are not easily predicted. Increases and decreases in types of mutation were frequently found not only in heterozygous and chimeric lines but also in putative biallelic lines, and the segregations were distorted even when the mutation type was stably transmitted. Various lines, e.g., OsAXO1a #2, OsAOX1b #3, OsAOX1c #4 and OsBEL #2, showed that the T-DNA region was segregating according to standard laws by the chi-square test, whereas the transmission of targeted mutations was disrupted (Table 2). One possible explanation is that the abnormal inheritance was caused by somatic mutations. For example, putative biallelic plants are actually chimeras with different homozygous mutations in separate cells. The mutations thus may have been lost or inherited unequally during germline segregation. Meanwhile, the PCR-based detection method has limitations in the detection of larger deletions because the PCR reaction would fail if the deletion removed the primer-binding sites. Therefore, the mutation frequency might be underestimated, and the failure of detection of the mutated allele might confound the analysis of inheritance patterns in certain lines. Moreover, it has been reported that different mutations can be detected in samples of different tissues26. Because we only examined the target sequence in a single leaf, it would not be surprising that some genotypes present in the rest of the plant were overlooked. Therefore, the additional mutations found in T1 might be transmitted from undetected T0 somatic mutations. Unexpected inheritance patterns of T0 plants have also been observed in other studies, but with lower frequency26,27. Although there are no significant differences in the mutation rates of the two CRISPR/Cas9 systems7,10, the differences in the system construction still might be a reason for the observed variation in the frequency of somatic mutations. Compared to the random and complicated genetic transmission in the first generation, the patterns are stable and easier to predict in later generations. Except for newly occurring mutations, all of the T2 genotypes were inherited normally from T1 plants in the presence or in the absence of the transgene (Fig. 1B), showing standard germline transmission.

Figure 1. Production of rice plants with inheritable desired mutations.

A, Schematic of the procedure for the generation and analysis of targeted mutated plants. The target site was selected using CRISPR-P or CRISPR-Plant tools and inserted into a binary vector to express sgRNA and Cas9. T0 plants were regenerated by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, and later generations were produced by strict self-pollination. In each generation, the targeted mutations were examined by site-specific PCR and sequential sequencing. B, The overview of the major inheritance patterns of transgene-positive T1 plants. A circle indicates that the plant carries the transgene in the genome. Green indicates the targeted regions. Yellow and red indicate different mutations on the target site. The indicated zygosity of homozygote (Ho), compound heterozygote (Com-He) and heterozygote (He) is putative.

Off-target events are an important concern in the application of CRISPR/Cas9 in plants. A double nicking approach, combining paired sgRNAs with distinct locations adjacent to the target site and a nickase version of mutated Cas9, was reported to effectively avoid off-target effects28,40, but it would limit the potential target range compared to the single sgRNA/Cas9 system. The off-target efficiency may vary greatly depending on the construction of CRISPR/Cas9, the organism and the transformation method. For the four different targets in this study, we found low-frequency mutations in only one off-target site, which had a 1-bp mismatch outside of the seed region, with on-target sites in the T1 generation plant in the presence of the transgene. These results indicate that the off-target effect is indeed quite low in rice targeted gene modification using the vector and transformation system described here. By selecting target sites with the help of bioinformatic tools34,35, we successfully generated mutations in three individual AOX1 family members, which is difficult to achieve using standard RNAi methods (data not shown) due to the high sequence similarity. These results demonstrate the reliability of software-aided target selection methods and also suggest that the off-target events in the highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9 system could be virtually avoided in rice-gene editing through careful sgRNA design.

In animals, biallelic mutations can be efficiently generated in one-cell-stage embryos by microinjecting an excessive amount of sgRNA and Cas9 RNA41,42,43. This method nearly guarantees reliable germline transmission both in theory and in practice. However, the integration of the CRISPR/Cas9 sequence into the genome is necessary for generating targeted modifications in plants. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of embryogenic calli is a common method for generating transgenic crops. The transformed cells soon divide, allowing only a short time window for generating the germline mutation. In contrast, the regeneration of transgenic crop plants from embryogenic cells normally requires several weeks or months, and the sgRNA/Cas9 complex should be continuously expressed during this period. This long expression period may give rise to the high risk of somatic mutations in the first generation. The intricate T0 segregation pattern in this report strongly supports the widespread occurrence of somatic mutations. In contrast, we revealed that T1 mutations, especially biallelic mutations, were stably transmitted to the next generation through germline transmission. An advantage of the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing is the potential for transgene-free progeny. Once the desired gene editing has been achieved, the transgene region can be easily segregated out in progeny via simple self-fertilization. In this study, we show that the T-DNA had indeed completely segregated out in the T1 generation, with the targeted mutation transmitting independently. In addition, our results reveal that off-target mutations were only found in the transgene-positive T1 plants. Therefore, the off-target effects might be largely reduced by selecting appropriate T1 progeny. Taken together, our results indicate that stable inheritance and “transgene clean” homozygous targeted gene editing can be produced in the T1 generation in CRISPR/Cas9-transgenic rice. Therefore, the system can be used as a simple, rapid and powerful molecular tool in crop variety improvement and will greatly advance molecular design in breeding.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Rice plants (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica) were used for plant transformation. Mature, non-dormant seeds were sterilized and germinated in 1/2 MS medium under a light/dark cycle of 16 h/8 h at 28 °C for at least 10 days. Rice seedlings at the trifoliate stage or regenerated rice after 4 weeks of rooting were transferred to plastic buckets in a greenhouse maintained at 30 °C during the day and 28 °C at night.

Vector construction and rice transformation

The oligonucleotides used for targeted mutagenesis were designed with the help of the CRISPR-P and CRISPR-PLANT tools34,35 and are listed in Supplemental Table S2. The Gateway-based CRISPR/Cas9 plant expression vectors were constructed as previously described7. The binary constructs were then introduced into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105. Embryonic calli from mature rice seeds were transformed by co-cultivation, selected with 50 mg/l hygromycin, and used to regenerate transgenic plants as previously described44. The numbers of transgene copies were determined using real-time PCR45.

Genotyping

Total DNA was extracted and purified from approximately 100 mg mature rice leaves followed by a previously described high-throughput method46. Specific PCR primers, as listed in Supplemental Table S2, were used to examine the presence of T-DNA regions. To detect mutations, the genomic regions surrounding on- and off- target sites were amplified using specific PCR primers. The fragments were directly sequenced using the corresponding site-specific primers or cloned into the pEASY-T vector and then Sanger-sequenced using the M13 primer.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Xu, R.-F. et al. Generation of inheritable and "transgene clean" targeted genome-modified rice in later generations using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 5, 11491; doi: 10.1038/srep11491 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Li-Jia Qu for providing the gateway-based OsCas9/sgRNA system. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31100216 and No. 31401454) and the Creative Foundation of the Anhui Agricultural Academy of Sciences (13C0101, 14A0101 and 14B0113).

Footnotes

Author Contributions P.W. and J.Y. designed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. R.X., R.Q., H.M. and C.Q. performed the vector construction and mutation genotyping. H.L., J.L., Y.Y. and L.L. performed the rice transformation, grew plants and followed the copy number and presence of T-DNA. R.X. and H.L. analyzed the data and drew pictures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Chen K., Gao C. TALENs: Customizable Molecular DNA Scissors for Genome Engineering of Plants. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 40, 271–279 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytas D. F. Plant Genome Engineering with Sequence-Specific Nucleases. Annual Review of Plant Biology 64, 327–350 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauser F. et al. In planta gene targeting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 7535–7540 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta H. & Fauser F. Gene targeting in plants: 25 years later. Int J Dev Biol 57, 629–637 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing H.-L. et al. A CRISPR/Cas9 toolkit for multiplex genome editing in plants. BMC Plant Biology 14, doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0327-y (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z. et al. Efficient genome editing in plants using a CRISPR/Cas system. Cell Res 23, 1229–1232 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J. et al. Targeted mutagenesis in rice using CRISPR-Cas system. Cell Res 23, 1233–1236 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay S. K., Kumar J., Alok A. & Tuli R. RNA-Guided Genome Editing for Target Gene Mutations in Wheat. G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics 3, 2233–2238 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z., Zhang K., Chen K. & Gao C. Targeted Mutagenesis in Zea mays Using TALENs and the CRISPR/Cas System. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 41, 63–68 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y. et al. Application of the CRISPR-Cas System for Efficient Genome Engineering in Plants. Molecular Plant 6, doi: 10.1093/mp/sst121 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K. & Yang Y. RNA-Guided Genome Editing in Plants Using a CRISPR–Cas System. Molecular Plant 6, 1975–1983 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-F. et al. Multiplex and homologous recombination-mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9. Nat Biotech 31, 688–691 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov V., Staskawicz B., Weigel D., Jones J. D. G. & Kamoun S. Targeted mutagenesis in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana using Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat Biotech 31, 691–693 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Q. et al. Targeted genome modification of crop plants using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotech 31, 686–688 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W. et al. Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Research 41, e188 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugano S. S. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Targeted Mutagenesis in the Liverwort Marchantia polymorpha L. Plant and Cell Physiology 55, 475–481 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Mol Biol 87, 99–110 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R., Gurevich V., Filler, S., Samach A. & Levy A. Comparative assessments of CRISPR-Cas nucleases’ cleavage efficiency in planta. Plant Mol Biol 87, 143–156 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H. & Wang N. Targeted Genome Editing of Sweet Orange Using Cas9/sgRNA. PLoS ONE 9, e93806 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat Biotech 32, 947–951 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R. et al. Gene targeting using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated CRISPR-Cas system in rice. Rice 7, 1–4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks C., Nekrasov V., Lippman Z. B. & Van Eck J. Efficient Gene Editing in Tomato in the First Generation Using the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-Associated9 System. Plant Physiology 166, 1292–1297 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z. et al. Multigeneration analysis reveals the inheritance, specificity, and patterns of CRISPR/Cas-induced gene modifications in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 4632–4637 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun Y. et al. Site-directed mutagenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana using dividing tissue-targeted RGEN of the CRISPR/Cas system to generate heritable null alleles. Planta 241, 271–284 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Yang B. & Weeks D. P. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing in Arabidopsis thaliana and Inheritance of Modified Genes in the T2 and T3 Generations. PLoS ONE 9, e99225 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. The CRISPR/Cas9 system produces specific and homozygous targeted gene editing in rice in one generation. Plant Biotechnology Journal 12, 797–807 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Liu B., Weeks D. P., Spalding M. H. & Yang B. Large chromosomal deletions and heritable small genetic changes induced by CRISPR/Cas9 in rice. Nucleic Acids Research, doi: 10.1093/nar/gku806 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauser F., Schiml S. & Puchta H. Both CRISPR/Cas-based nucleases and nickases can be used efficiently for genome engineering in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 79, 348–359 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotech 31, 822–826 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. D. et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotech 31, 827–832 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanayak V. et al. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat Biotech 31, 839–843 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M., Mikami M. & Toki S. Multi-gene knockout utilizing off-target mutations of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology, doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu154 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P. et al. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotech 31, 833–838 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y. et al. CRISPR-P: A Web Tool for Synthetic Single-Guide RNA Design of CRISPR-System in Plants. Molecular Plant 7, 1494–1496 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K., Zhang J. & Yang Y. Genome-Wide Prediction of Highly Specific Guide RNA Spacers for CRISPR–Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing in Model Plants and Major Crops. Molecular Plant 7, 923–926 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M., Zhou S.-R. & Xue H.-W. CRISPR Primer Designer: Design primers for knockout and chromosome imaging CRISPR-Cas system. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, doi: 10.1111/jipb.12295 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deriano, L. & Roth D. B. Modernizing the Nonhomologous End-Joining Repertoire: Alternative and Classical NHEJ Share the Stage. Annual Review of Genetics 47, 433–455 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu G. T. H. et al. Repair of Site-Specific DNA Double-Strand Breaks in Barley Occurs via Diverse Pathways Primarily Involving the Sister Chromatid. Plant Cell 26, 2156–2167 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerhofer R. et al. T-DNA integration: a mode of illegitimate recombination in plants. The EMBO Journal 10, 697–704 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiml S., Fauser F. & Puchta H. The CRISPR/Cas system can be used as nuclease for in planta gene targeting and as paired nickases for directed mutagenesis in Arabidopsis resulting in heritable progeny. The Plant Journal 80, 1139–1150 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang N. et al. Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in Zebrafish embryos. Cell Res 23, 465–472 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland A. E. et al. Heritable genome editing in C. elegans via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Meth 10, 741–743 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al. One-Step Generation of Mice Carrying Mutations in Multiple Genes by CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Genome Engineering. Cell 153, 910–918 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y. et al. An efficient and high-throughput protocol for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation based on phosphomannose isomerase positive selection in Japonica rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Rep 31, 1611–1624 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. et al. Estimating the copy number of transgenes in transformed rice by real-time quantitative PCR. Plant Cell Rep 23, 759–763 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. A high-throughput, high-quality plant genomic DNA extraction protocol Genetics and Molecular Research 12, 4526–4539 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.