Abstract

Context:

Insulin resistance (IR) and type 2 diabetes are increasing, particularly in Hispanic (H) vs non-Hispanic White (NHW) populations. Adiponectin has a known role in IR, and therefore, understanding ethnic and sex-specific behavior of adiponectin across the lifespan is of clinical significance.

Objective:

To compare ethnic and sex differences in adiponectin, independent of body mass index, across the lifespan and relationship to IR.

Design:

Cross-sectional.

Setting:

Primary care, referral center.

Patients:

A total of 187 NHW and 117 H participants (8–57 y) without diabetes. Life stage: pre-/early puberty (Tanner 1/2), midpubertal (Tanner 3/4), late pubertal (Tanner 5, <21 years), and adult (Tanner 5, ≥21).

Interventions:

None.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

Fasting adiponectin, insulin, glucose, and revised homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance.

Results:

Adiponectin was significantly inversely correlated with revised homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance. Regarding puberty, adiponectin trended downward in late puberty, but only males were significantly lower in adulthood. By sex, adiponectin was lower in adult males vs females of both ethnicities. Regarding ethnicity, H adults of both sexes had lower adiponectin than NHW adults. Of note, in NHW females, adiponectin trended highest in adulthood, whereas in H females, adiponectin fell in late puberty and remained lower in adulthood.

Conclusions:

Adiponectin inversely correlated with IR, trended down in late puberty, and was lowest in adult males. H adults of both sexes had lower adiponectin than NHW adults, and H females followed a more “male pattern,” lacking the rebound in adiponectin seen in NHW females after puberty. These data suggest that adiponectin, independent of body mass index, may relate to the greater cardiometabolic risk seen in H populations and in particular H females.

Adiponectin correlates with insulin resistance and has both ethnic and sex differences across a range of age and pubertal status. Hispanic females appear to lack the protective effect of female sex.

Racial, ethnic, and sex differences exist in the incidence and prevalence of insulin resistance (IR) and type 2 diabetes. Specifically, Hispanics (Hs) and African-Americans have a higher incidence and prevalence of these disorders when compared with non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs) even after controlling for obesity (1–4). Further, among youth, rates of obesity and IR are increasing, particularly among African-Americans, Native Americans, and Hs (1, 5), and rates of youth-onset type 2 diabetes are higher in girls (6). However, the biology behind the differential risks is not fully understood.

Adiponectin, an adipokine primarily secreted by the adipocyte (7), is known to be involved in lipid regulation, insulin sensitivity, and cardiovascular health (8–10) and is known to have antiinflammatory and antiatherogenic properties (11, 12). Adiponectin concentrations are lower in adults with IR, type 2 diabetes, and/or cardiovascular disease (8, 9, 13) and lower in adult males vs adult females (14–16). These trends are also present in youth (12, 17–21). Additionally, a reduction of adiponectin has been shown to precede the development of metabolic or obesity-related disorders (22–24). Given the rise in obesity and related metabolic disorders in both adults and children, especially in particular racial/ethnic groups and in adolescent females, racial/ethnic and sex differences in the regulation of adiponectin across the lifespan are of significant importance. However, the relationship of adiponectin to sex and race/ethnicity across the lifespan remains poorly understood.

Previous studies in adults who are African-American, H, American Indian, and Asian have shown lower circulating levels of adiponectin when compared with NHW (8, 25–29). Further, lower circulating adiponectin concentrations have been found in H vs NHW adults with cardiovascular disease risk factors, independent of obesity markers, diabetes status, or sex (28). Additionally, hypoadiponectinemia has been shown to be an independent risk factor for developing metabolic syndrome in Latino youth (18), and adiponectin appears to be lower during puberty (20, 30, 31).

However, despite these smaller uni-comparison studies, studies examining the interaction between sex, ethnicity, and pubertal status are lacking. Therefore, we aimed to assess ethnic and sex differences in adiponectin across all stages of life (from prepuberty to adulthood), independent of body mass index (BMI), in a population of nondiabetic H and NHW children and adults, as well as the association between adiponectin and IR.

Materials and Methods

In total, 304 participants, 117 H and 187 NHW, were studied. Protocols were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board (Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board) before any data collection. Participants for the pediatric data were recruited from Children's Hospital Colorado Obesity Clinics, Adolescent Medicine Clinics, General Pediatric Clinics, and community General Pediatric offices as well as from University of Colorado Anschutz Campus advertisements, community advertisements, newspaper advertisements, or word of mouth. Parental informed consent and child assent were obtained from all participants under 18 years and participant consent for all participants 18 years or older before enrollment. Adult participants were recruited from community advertisements, University of Colorado Adult Endocrine Clinics, and University of Colorado Anschutz Campus advertisements.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants were self-identified as either H or NHW race, 8–57 years of age, weight under 300 pounds, had no history of diabetes (with an oral glucose tolerance test ruling out diabetes) or polycystic ovarian syndrome, had no other major chronic illnesses, and were not on any chronic medications known to affect lipid metabolism, glucose tolerance, or insulin sensitivity (such as atypical antipsychotics, oral steroids, metformin, thiazolidinediones, insulin, weight loss medications, etc). Pregnant or lactating women were also excluded. For the pediatric population, normal weight was described as having a BMI under the 85th percentile for age and sex, and overweight/obese was described as having BMI more than or equal to 85th percentile for age and sex. For the adult population, normal weight was described as having a BMI less than 25 kg/m2, and overweight/obese was described as having a BMI more than or equal to 25 kg/m2.

The participants were enrolled into the study between 2008 and 2014. Parameters including height, weight, BMI, waist circumference, and pubertal stage (Tanner criteria) were obtained at the screening clinical visit by a trained medical provider. In the pediatric participants, pubertal status was determined by physical examination using standard Tanner staging by a pediatric endocrinologist. “Pre-/early pubertal” was defined as Tanner stage 1 or 2 (n = 99), “midpubertal” was defined as Tanner stage 3 or 4 (n = 54), “late pubertal” was defined as Tanner stage 5 development and age under 21 years (n = 37), and “adult” was defined as Tanner 5 development and age greater than or equal to 21 years (n = 114).

All baseline laboratory data were collected uniformly across the cohorts using standard technique in the morning following a minimum of an 8-hour fast, followed by a standard 75-g oral glucose tolerance test. The following data were collected: fasting and 2-hour glucose, fasting insulin, and total adiponectin. All samples were analyzed at the University of Colorado Hospital Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC) core lab using standard methods. Glucose was measured using a hexokinase assay (sensitivity 10 mg/dL, 0.67%–1.44% precision; Beckman Coulter) or using YSI (sensitivity 10 mg/dL, 1.0%–3.6% precision; Yellow Springs Instrument). Adiponectin was batched monthly and therefore samples from each of the cohorts were stored for a similar time before analyses. Adiponectin was analyzed using a highly controlled RIA, which is interrogated quarterly by the CTRC for quality assurance including intra- and interassay variability (sensitivity 1.0 μg/mL, 3.9%–8.5% precision; Millipore). Insulin was also measured using a high sensitivity RIA at the CTRC (sensitivity 3 μU/mL, 5.2%–9.8% precision; Millipore). The revised homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA2-IR) was calculated using fasting glucose and insulin levels as widely described (32).

Statistical analysis

Participants with missing data for any of the primary variables of interest (adiponectin, pubertal stage, sex, and ethnicity) were excluded from analysis. BMI percentile and z score (BMIz) were calculated according to the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. BMI percentile is only calculable from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts for participants up to 239.5 months of age; therefore, participants older than this were treated as if they were 239.5 months of age. The distributions of the variables of interest were assessed and log transformation applied as needed. The χ2 or Fisher's exact test was used to test the association of categorical variables. Spearman's and Pearson's correlation coefficients and linear models were used to test the association of continuous variables. The linear models and correlations were adjusted for BMIz, with the exception of the correlation between waist circumference and adiponectin. BMIz was used as a covariate rather than waist circumference, as waist circumference varies with age, sex, and ethnicity, whereas BMIz is a variable already adjusted for age and sex.

In order to examine the relationship of adiponectin with life stage, sex, and ethnicity, we began with an ANOVA model with a three-way interaction between life stage, sex, and ethnicity. Although the three-way interaction was not significant, we performed pairwise comparisons between groups formed by the crossing of the 3 factors as an exploratory analysis. Next, we removed the three-way interaction from the model in order to examine the significance of the two-way interactions (life stage by sex, life stage by ethnicity, and sex by ethnicity).

Results

Participant characteristics are shown by life stage in Table 1. In total, there were 304 participants, 164 were females (54%) and 140 were males (46%). There was a higher percentage of pre-/early pubertal and adult participants (32.5% and 37.5%, respectively) compared with mid- and late pubertal participants (17.8% and 12.2%, respectively). There was also a slightly higher number of normal weight vs overweight/obese individuals studied overall (n = 165, 54.3% and n = 139, 45.7%, respectively).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Life Stage

| Life Stage |

Total n = 304 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-/Early Pubertal (TS 1,2) n = 99 |

Midpubertal (TS 3,4) n = 54 |

Late Pubertal (TS 5, <21 y) n = 37 |

Adult (TS 5, ≥21 y) n = 114 |

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Female | 44 | 44.4 | 22 | 40.7 | 32 | 86.5 | 66 | 57.9 | 164 | 53.9 |

| Male | 55 | 55.6 | 32 | 59.3 | 5 | 13.5 | 48 | 42.1 | 140 | 46.1 |

| NHW | 47 | 47.5 | 26 | 48.1 | 22 | 59.5 | 92 | 80.7 | 187 | 61.5 |

| H | 52 | 52.5 | 28 | 51.9 | 15 | 40.5 | 22 | 19.3 | 117 | 38.5 |

| Normal weight | 57 | 57.6 | 30 | 55.6 | 9 | 24.3 | 69 | 60.5 | 165 | 54.3 |

| Ow/Ob | 42 | 42.4 | 24 | 44.4 | 28 | 75.7 | 45 | 39.5 | 139 | 45.7 |

TS, Tanner stage; Ow/Ob, overweight/obese.

Descriptive characteristics for life stage, BMI, and HOMA2-IR by sex and race are shown in Table 2. There were significantly more males than females in the pre-/early puberty group (P < .001) and more Hs in this group (P < .001). Additionally, the H group had significantly higher BMI z scores, HOMA2-IR, and waist circumference than the NHW group (P < .001 for all comparisons); however, this was not observed in males compared with females (Table 2).

Table 2.

Life Stage, HOMA2-IR, BMI z Score, and Waist Circumference by Sex and Race

| Female | Male | P Value | NHW | H | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life stage N (%) | ||||||

| Pre-/early pubertal (TS 1,2) | 44 (26.83) | 55 (39.29) | <.001 | 47 (25.13) | 52 (44.44) | <.001 |

| Midpubertal (TS 3,4) | 22 (13.41) | 32 (22.86) | 26 (13.90) | 28 (23.93) | ||

| Late pubertal (TS 5, <21 y) | 32 (19.51) | 5 (3.57) | 22 (11.76) | 15 (12.82) | ||

| Adult (TS 5, ≥21 y) | 66 (40.24) | 48 (34.29) | 92 (49.20) | 22 (18.80) | ||

| HOMA2-IR | 1.66 (1.12) | 1.65 (1.66) | .982 | 1.33 (1.29) | 2.17 (1.41) | <.001 |

| BMIz | 0.86 (1.12) | 0.63 (1.14) | .069 | 0.40 (1.05) | 1.32 (1.03) | <.001 |

| Waist (cm) | 80.2 (15.18) | 82.0 (17.94) | .379 | 77.2 (14.53) | 86.3 (17.56) | <.001 |

TS, Tanner stage. Statistics presented are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

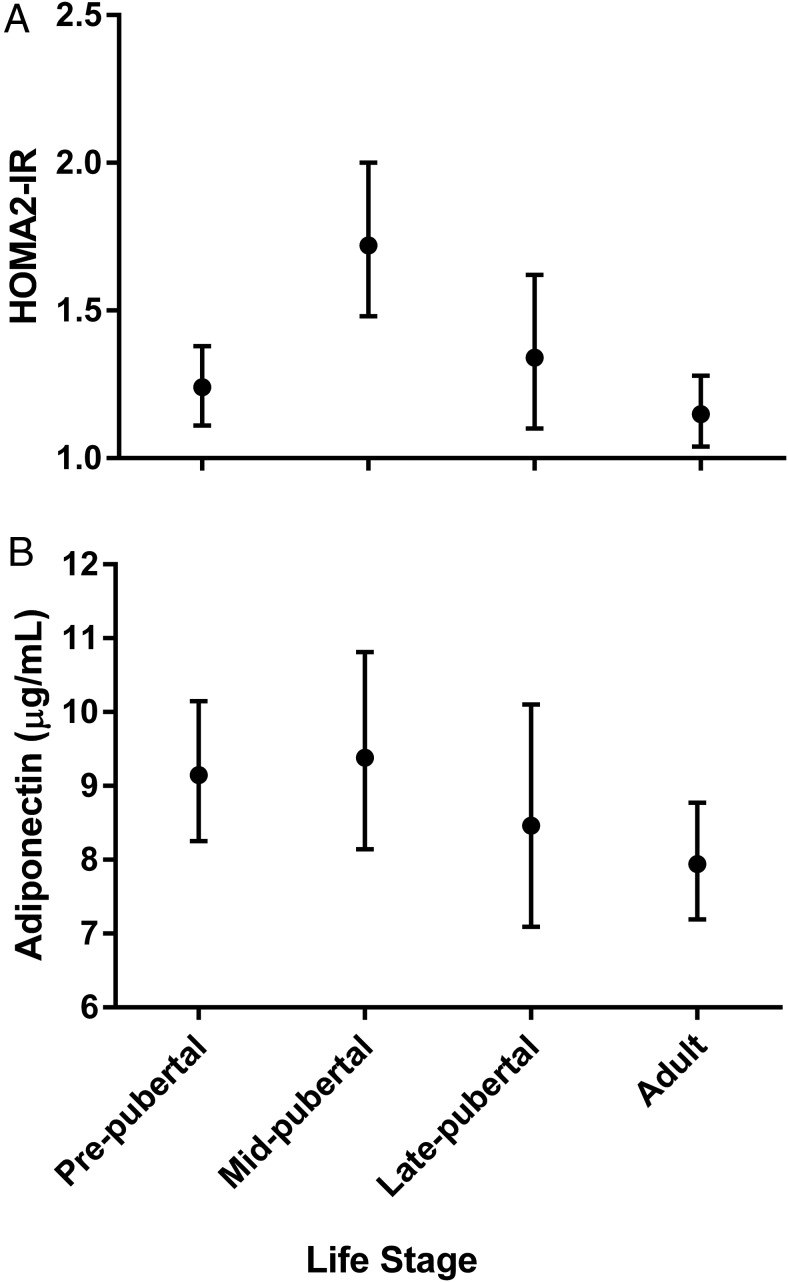

Fasting glucose, insulin, and HOMA2-IR by life stage are displayed in Table 3. Insulin sensitivity was lowest (highest HOMA2-IR) in the midpubertal group, followed by the late pubertal group (Table 3 and Figure 1A). Adiponectin tended to be lowest in the late pubertal and adult groups when compared with the other life stages after controlling for BMIz (pre-/early pubertal least squares geometric mean 9.15 μg/mL [95% CI 8.25–10.15], midpubertal 9.38 μg/mL [8.14–10.81], late pubertal 8.46 μg/mL [7.09–10.10], and adult 7.94 μg/mL [7.19–8.77]; P = .15 for association with lifespan) (Figure 1B). Overall, adiponectin was significantly inversely associated with HOMA2-IR (r = −0.26, P < .0001) and remained so after controlling for BMIz (r = −0.15, P = .01). Overall, waist circumference was also significantly inversely correlated with adiponectin (r = −0.31229, P < .0001), and Hs had a significantly larger waist circumference than NHW (P < .0001). This pattern remained true within males (P = .0005) and females (P = .004).

Table 3.

Fasting Glucose, Insulin, and HOMA2-IR by Life Stage

| Life Stage |

P Value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-/Early Pubertal (TS 1,2) n = 99 |

Midpubertal (TS 3,4) n = 54 |

Late Pubertal (TS 5, <21 y) n = 37 |

Adult (TS 5, ≥21 y) n = 114 |

||||||

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | ||

| Glucose | 84.99 | 83.4–86.6 | 86.9 | 84.7–89.1 | 81.55 | 79.0–84.2 | 86.62 | 85.1–88.2 | .0079 |

| Insulin | 10.23 | 9.12–11.48 | 13.67 | 11.7–16.0 | 11.02 | 9.05–13.4 | 9.13 | 8.17–10.2 | .0007 |

| HOMA2-IR | 1.24 | 1.11–1.38 | 1.72 | 1.48–2.0 | 1.34 | 1.10–1.62 | 1.15 | 1.04–1.28 | .0004 |

Geometric means and 95% CIs for fasting glucose (mg/dL), fasting insulin (μU/mL), and HOMA2-IR by life stage, adjusted for BMI z score. TS, Tanner stage.

Figure 1.

HOMA2-IR and adiponectin by life stage. A, Least squares geometric means and 95% CIs of HOMA2-IR adjusted for BMI z score. P value for association with lifespan, P = .0004. B, Least squares geometric means and 95% CIs of adiponectin adjusted for BMI z score. P value for association with lifespan, P = .15.

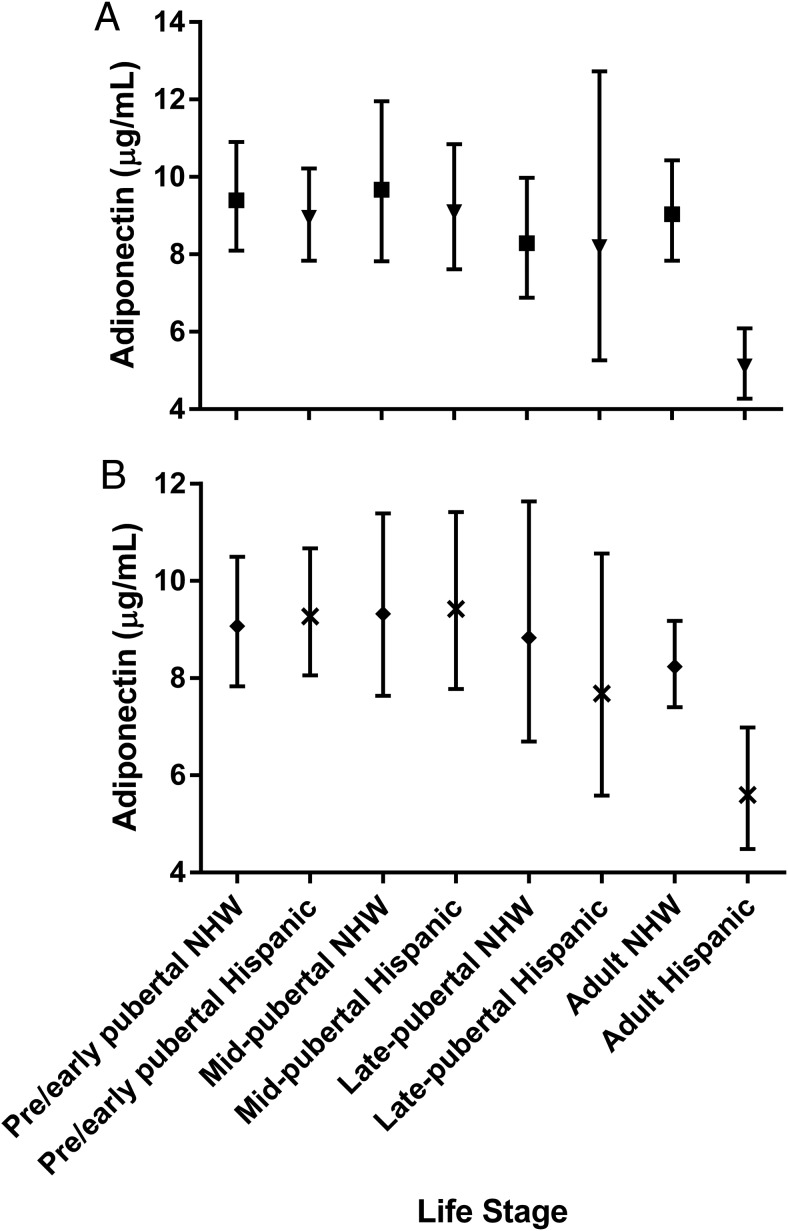

There was a significant interaction between life stage and sex (P = .0018) when adjusted for BMIz, particularly within males. Male adults (both H and NHW) had lower adiponectin than pre- and midpubertal males (pre-/early least squares geometric mean 8.95 μg/mL [7.83–10.22; P < .0001 vs adults], midpubertal 9.09 μg/mL [7.61–10.85; P < .0001 vs adults], late pubertal 8.19 μg/mL [5.26–12.73; P = .05 vs adults], and adult 5.10 μg/mL [4.27–6.09]). Additionally, adult males had lower adiponectin than adult females (mean 9.04 μg/mL [7.84–10.43; P < .0001]) (Figure 2A). Within females, adiponectin trended lowest in late puberty and recovered in adulthood; however, this difference was not significant (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Adiponectin by life stage, sex, and race. A, Least squares geometric means and 95% CIs, adjusted for BMI z score, within male (triangle) and female (square) participants. P values for pairwise comparisons within males: P < .0001 pre-/early pubertal vs adults; P < .0001 midpubertal vs adults; P = .05 late pubertal vs adults. P values for pairwise comparisons of adult males vs adult females: P < .0001. P values for pairwise comparisons within females, P = NS. B, Least squares geometric means and 95% CIs adjusted for BMI z score, within NHW (diamond) and H (X) participants. P values for pairwise comparisons within Hs: adult vs pre-/early pubertal, P = .0002; adult vs midpubertal, P = .0005; late pubertal vs pre-/early pubertal, P = .28; late pubertal vs midpubertal, P = .28.

There was an interaction between life stage and ethnicity, due to differences by life stage, within the H group (P = .0644) (Figure 2B). Adjusting for BMIz, adiponectin was lower in the H adult life stage (5.60 μg/mL [4.49–6.98]) when compared with H pre- and midpubertal stages. Mean adiponectin in the pre-/early pubertal H group was 9.27 μg/mL (8.06–10.67; P = .0002 vs adults), midpubertal H group was 9.42 μg/mL (7.77–11.41; P = .0005 vs adults), and late pubertal H group was 7.68 μg/mL (5.59–10.56). The late pubertal group was not significantly different from any of the other life stages but was intermediate between the earlier stages and low levels of adulthood. These differences were not observed in the NHW group (Figure 2B).

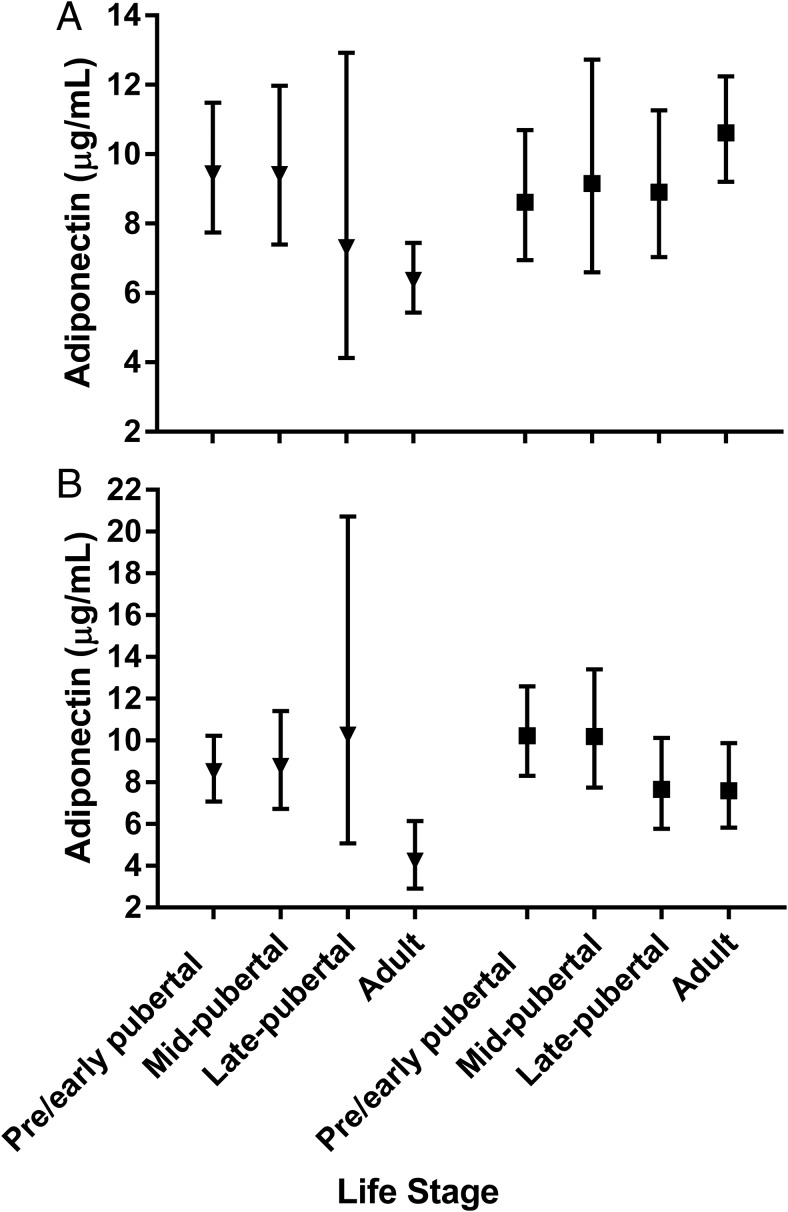

Although the three-way interaction of life stage, sex, and ethnicity was not significant, there were trends towards ethnic differences across the lifespan by sex, after adjusting for BMIz (Figure 3). In NHW females, there was a trend toward adiponectin being highest in adults vs the other life stages; however, this difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, in NHW males adiponectin began to fall in late puberty (mean 7.30 μg/mL [4.13–12.92]) and fell further in the adult group (mean 6.36 μg/mL [5.44–7.45], P = .002 vs pre-/early pubertal and P = .008 vs pubertal groups). Additionally, NHW male adults had lower adiponectin when compared with NHW female adults (mean 10.62 μg/mL [9.21–12.25]; P < .001) (Figure 3). Similar to the NHW males, in H males, adiponectin was lowest in the adults (mean 4.23 μg/mL [2.91–6.14]) compared with the other life stages (pre-/early puberty mean 8.51 μg/mL [7.07–10.23; P = .0011], midpubertal 8.76 μg/mL [6.72–11.41; P = .0019], and late pubertal 10.26 μg/mL [5.08–20.72; P = .029]). Further, H male adults tended to have lower adiponectin than NHW male adults (P = .05) (Figure 3). However, H females had a different pattern than NHW females, with lower adiponectin occurring in the late puberty and adult groups (mean 7.65 μg/mL [5.78–10.13] and 7.58 μg/mL [5.83–9.87], respectively). Therefore, adult H females had significantly lower adiponectin than adult NHW females (P = .029). Despite this, a sex difference remained within H adults, with higher adiponectin in the H female adults than in the H male adults (P = .013) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adiponectin within NHW and H participants by life stage and sex. A, Least squares geometric means and 95% CIs, adjusted for BMI z score, within NHW males (triangle) and females (square) participants. P values for three-way interaction within males: adult vs pre-/early pubertal, P = .0021; adult vs midpubertal, P = .0076; adult vs late pubertal, P = .65. P values for three-way interaction within females, P = NS. B, Least squares geometric means and 95% CIs, adjusted for BMI z score, within H males (triangle) and females (square) participants. P values for three-way interaction within males: adult vs pre-/early puberty, P = .0011; adult vs midpubertal, P = .0019; adult vs late pubertal, P = .029. P values for three-way interaction within females, P = NS. P value for three-way interaction within male adults (NHW vs H), P = .05. P value for three-way interaction within female adults (NHW vs H), P = .029.

Discussion

This study uniquely assesses the interactions between adiponectin, ethnicity, and sex over the lifespan within a large population of nondiabetic H and NHW youth and adults, adjusted for BMI. Our data confirm previous findings that adiponectin is inversely and independently associated with IR in these 2 populations. Across the cohort, adiponectin tended to decrease in late puberty when controlled for BMI, likely secondary to the decreased insulin sensitivity characteristic of puberty, but also displayed a sex difference, because it more significantly decreased in males in adulthood, likely secondary to the impact of sex steroids (33, 34). In addition, adiponectin had an ethnic difference, being lower in H vs NHW adults of both sexes. Of note, adiponectin in NHW females tended to decrease in late puberty but then recover in adulthood. However, H females did not follow this pattern and instead had a more “male pattern” of adiponectin decreasing in late puberty and staying lower in adulthood. Thus, sex and ethnic differences in adiponectin begin to emerge in puberty and become most prominent in adulthood, suggesting potential mechanistic clues to adiponectin physiology.

The patterns of adiponectin concentrations across the lifespan varied with sex and pubertal stage. Within both the NHW and H groups, adult males had significantly lower levels of adiponectin than adult females, thus the sex difference in adiponectin becomes most apparent in adulthood. When looking at all males (H and NHW), adiponectin was lowest in adults when compared with the other life stages. Conversely, when looking at NHW females, we observed a trend toward higher adiponectin in adults. These findings reinforce previous findings looking at sex and pubertal differences in adiponectin. The lower circulating levels of adiponectin in adult males compared with adult females (14, 15) may be related to testosterone, because inverse correlations between androgens and adiponectin have been described (14, 20). This sex difference in adiponectin in adults could be one factor contributing to the higher rates of cardiovascular disease in adult men compared with women.

Studies in pediatric populations examining the relationships between sex steroids, pubertal stage, and adiponectin are not as clear. Böttner et al (20) found that adiponectin decreases throughout puberty in normal weight boys (but not girls) and is inversely related to testosterone and Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate levels, leading to lower adiponectin levels in adolescent males vs females. These findings were similar to previous reports that showed a decline in adiponectin in midpuberty in boys, which resulted in pubertal males having lower adiponectin levels than females (30). Lu et al (31) found that both boys and girls have a decrease in adiponectin during puberty but that the rate of decrease is faster in boys than girls. Riestra et al (19) found no significant relationships between adiponectin and testosterone (or estradiol) in a population of pubertal children in Spain but did show a direct correlation between adiponectin and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), as well as an inverse relationship to the free androgen index (independent of BMI, waist circumference, and fat mass). Further, decreased levels of SHBG have been associated with decreased adiponectin in adult populations (35), but this relationship may be confounded by IR, because SHBG is also known to be low in IR individuals (36). Again, in the current study, we found sex differences in adiponectin across pubertal stages, with adult males having the lowest concentrations vs adult NHW females having the highest concentrations. We also found that the largest variability in adiponectin was in late pubertal males, likely because of the variability in the timing of achieving a full adult testosterone level in adolescent males. Further studies including sex hormone comparisons across pubertal stages would be useful in our understanding of this relationship.

Our cohort also displayed a difference in ethnic patterns of adiponectin when separated by sex. Similar to what has been observed by others (25, 28), we found that H adult males had lower adiponectin levels than NHW adult males. Further, in contrast to our observations in NHW females, in H females, adiponectin was lower in late puberty, independent of BMI, but did not recover in adulthood (therefore resulting in significantly lower adiponectin in adult H females compared with adult NHW females), a pattern similar to that seen in the male participants. Our results suggest that adiponectin may relate to the increased risk of cardiometabolic disease seen in H vs NHW females, independent of BMI, because H females lacked the potential cardiovascular protection of female sex on adiponectin. H women are known to have the highest prevalence of metabolic syndrome compared with women of other ethnic groups (37) as well as lower adiponectin levels when compared with NHW females (37, 38). One explanation could be a greater degree of abdominal fat in H women compared with NHW women, because abdominal obesity is more closely correlated to metabolic dysfunction than total body fat (39). In this study, we did find that H females had a significantly larger waist circumference when compared with NHW females. However, a previous study has shown lower adiponectin levels in Mexican American adults independent of waist circumference (28). Another potential explanation is higher rates of polycystic ovarian syndrome in H females, resulting in higher androgens, an area in need of further research. Further, the relationship between adiponectin and adiposity or metabolic dysfunction may not be consistent across ethnicities (25, 38). For example, although King et al (38) found a negative relationship between BMI, adiponectin, waist circumference, fasting glucose, and IR in NHW women, this association was not significant within H women. Hulver et al (25) saw a similar trend in an African-American population. In support, Wolfgram et al (40) have shown that nonobese H girls have a greater degree of IR for a given amount of hepatic fat when compared with nonobese NHW girls, a difference not explained by BMI alone. Therefore, it is possible that sex hormones or other factors changing in late puberty may differentially regulate adiponectin in different ethnic groups. Additionally, our data argue that midlate puberty is an important time period in need of further research, as the sex and ethnic differences in adiponectin emerging during this time may be a potential window for interventions to prevent cardiometabolic disease before it is established in adulthood.

Our study has several limitations. First of all, our population had more females than males (especially in the late pubertal group). However, most of the significant differences were found in males, which suggest that the power to identify sex differences was adequate. We also did not include analysis of sex steroids in the current study, which are important potential contributors to sex differences. Additionally, in the analysis of the three-way interaction of life stage, sex, and ethnicity, the number of participants in some of the groups was very small. Additional studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm our conclusions. Further, most participants in the late puberty group were obese, and although our analysis was adjusted for BMI, we did not adjust for abdominal adiposity specifically. We also were not powered to analyze whether there is a relationship between adiponectin and physical activity and/or diet, because these measures were not routinely obtained in all of our study participants. Additionally, this is a cross-sectional study, so trends over time can only be suggested. Furthermore, most participants in this study were recruited from the greater Denver, CO, area. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to other populations across the nation. Lastly, although the homeostasis model (HOMA2-IR) used in this study is a surrogate marker of insulin sensitivity, it has acceptable validity for estimating IR in large population studies (32). Despite these limitations, our study is unique in its number of participants spread over a large portion of the lifespan in a single study, allowing direct comparisons.

Conclusions

Sex and ethnic differences in adiponectin begin to emerge in puberty and become most prominent in adulthood, suggesting potential mechanistic clues to adiponectin physiology. Adiponectin inversely correlated with IR, trended down in late puberty and was lowest in adult males. H adults of both sexes had lower adiponectin than NHW adults and H females followed a more male pattern, lacking the rebound in adiponectin seen in NHW females after puberty. These data suggest that adiponectin, independent of BMI, may relate to the greater cardiometabolic risk seen in H populations and in particular H females. This study uniquely identifies a connection between ethnicity, sex, and pubertal status and the development of IR and metabolic disease risk. Further studies assessing adiponectin with a longitudinal cohort including other ethnicities, and including sex steroids, are needed to confirm these results.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Adult General Clinical Research Center National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant M01-RR00051, the Pediatric Clinical Translational Research Center NIH Grant 5MO1 RR00069, and the Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Award Grant UL1 TR001082 from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH. D.H.B. was supported by the NIH Grant P30-DK048520. M.C.-G. was supported by a Pediatric Endocrine Society fellowship, the American Heart Association Grant CRP 13CRP1412001, the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health Grant K12-HD057022, a Pediatric Endocrinology Fellowship training grant, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant T32 DK063687, the Thrasher Pediatric Research Foundation, the Center for Women's Health Research, and the Endocrine Society Women's Health Fellowship. M.M.K was supported by the American Diabetes Association Junior Faculty Award 1-11-JF-23 and the NIH/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health Grant K12 HD057022-04. K.J.N. was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant 5-2008-291, the American Diabetes Association Grant 7-11-CD-08, and NIH Grants K23 RR020038-05 and R56 DK088971. T.A.S. was supported by the Clinical and Translational Research Institute Community and Academic Engagement Pilot, the American Heart Association Fellowship Award, the Thrasher Research Foundation New Scholar Award, and The Children's Hospital Research Institute Scholar Award.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMI

- body mass index

- BMIz

- BMI percentile and z score

- CTRC

- Clinical and Translational Research Center

- H

- Hispanic

- HOMA2-IR

- revised homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- IR

- insulin resistance

- NHW

- non-Hispanic White

- SHBG

- sex hormone-binding globulin

- 95% CI

- 95% confidence interval.

Reference

- 1. Crawford PB, Story M, Wang MC, Ritchie LD, Sabry ZI. Ethnic issues in the epidemiology of childhood obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:855–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mather KJ, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Adiponectin, change in adiponectin, and progression to diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes. 2008;57:980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ho RC, Davy KP, Hickey MS, Summers SA, Melby CL. Behavioral, metabolic, and molecular correlates of lower insulin sensitivity in Mexican-Americans. Am J Pshysiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E799–E808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960–1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rosenbaum M, Fennoy I, Accacha S, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in clinical and biochemical type 2 diabetes mellitus risk factors in children. Obesity. 2013;21(10):2081–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Copeland KC, Zeitler P, Geffner M, et al. Characteristics of adolescents and youth with recent-onset type 2 diabetes: the TODAY cohort at baseline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):159–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26746–26749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1930–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weiss R, Taksali SE, Dufour S, et al. The “obese insulin-sensitive” adolescent: importance of adiponectin and lipid partitioning. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3731–3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldstein BJ, Scalia R. Adiponectin: a novel adipokine linking adipocytes and vascular function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2563–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, et al. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived plasma protein, inhibits endothelial NF-κB signaling through a cAMP-dependent pathway. Circulation. 2000;102:1296–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magge SN, Stettler N, Koren D, et al. Adiponectin is associated with favorable lipoprotein profile, independent of BMI and insulin resistance, in adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(5):1549–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rigamonti AE, Agosti F, De Col A, et al. Severely obese adolescents and adults exhibit a different association of circulating levels of adipokines and leukocyte expression of the related receptors with insulin resistance. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nishizawa H, Shimomura I, Kishida K, et al. Androgens decrease plasma adiponectin, an insulin-sensitizing adipocyte-derived protein. Diabetes. 2002;51:2734–2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Degawa-Yamauchi M, Dilts JR, Bovenkerk JE, Saha C, Pratt JH, Considine RV. Lower serum adiponectin levels in African American boys. Obesity Res. 2003;11(11):1384–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanley AJ, Bowden D, Wagenknecht LE, et al. Associations of adiponectin with body fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic hispanics and African-Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2665–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bacha F, Gungor N, Saad R, Arslanian SA. Adiponectin in youth: relationship to visceral adiposity, insulin sensitivity, and β-cell function. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shaibi GQ, Cruz ML, Weigensberg MJ, et al. Adiponectin independently predicts metabolic syndrome in overweight Latino youth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(5):1809–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riestra P, Garcia-Anguita A, Ortega L, Garces C. Relationship of adiponectin with sex hormone levels in adolescents. Horm Res Pediatr. 2013;79:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Böttner A, Kratzsch J, Müller G, et al. Gender differences of adiponectin levels develop during the progression of puberty and are related to serum androgen levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4053–4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pérez CM, Ortiz AP, Fuentes-Mattei E, et al. High prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in Hispanic adolescents: correlations with adipocytokines and markers of inflammation. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16:865–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hotta K, Funahashi T, Bodkin NL, et al. Circulating concentrations of the adipocyte protein adiponectin are decreased in parallel with reduced insulin sensitivity during the progression of type 2 diabetes in rhesus monkeys. Diabetes. 2001;50:1126–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindsay RS, Funahashi T, Hanson RL, et al. Adiponectin and development of type 2 diabetes in the Pima Indian population. Lancet. 2002;360:57–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stefan N, Vozarova B, Funahashi T, et al. Plasma adiponectin concentration is associated with skeletal muscle insulin receptor tyrosine phosphorylation, and low plasma concentration precedes a decrease in whole-body insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes. 2002;50:1884–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hulver MW, Saleh O, MacDonald K, Pories W, Barakat HA. Ethnic differences in adiponectin levels. Metabolism. 2004;52(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bush NC, Darnell BE, Oster RA, Goran MI, Gower BA. Adiponectin is lower among African Americans and is independently related to insulin sensitivity in children and adolescents. Diabetes. 2005;54:2772–2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schutte AE, Huisman HW, Schutte R, et al. Differences and similarities regarding adiponectin investigated in African-American and Caucasian women. Eur J Endocriol. 2007;157:181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pereira RI, Wang C, Hosokawa P, et al. Circulating adiponectin levels are lower in Latino versus non-Latino white patients at risk for cardiovascular disease, independent of adiposity measures. BMC Endocr Disord. 2011;11(13):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee S, Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian S. Racial differences in adiponectin in youth: relationship to visceral fat and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(1):51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martos-Moreno GA, Barrios V, Argente J. Normative data for adiponectin, resistin, interleukin 6, and leptin/receptor ratio in a healthy Spanish pediatric population: relationship with sex steroids. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu X, Ming L, Yin J, et al. Change of body composition and adipokines and their relationship with insulin resistance across pubertal development in obese and non-obese Chinese children: the BCAMS study. Int J Endocrinol. 2012;1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1487–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moran A, Jacobs DR, Jr, Steinberger J, et al. Insulin resistance during puberty: results from clamp studies in 357 children. Diabetes. 1999;48:2039–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goran MI, Gower BA. Longitudinal study on pubertal insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2001;50(11):2444–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tworoger SS, Mantzoros C, Hankinson SE. Relationship of plasma adiponectin with sex hormone and insulin-like growth factor levels. Obesity. 2007;15:2217–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winters SJ, Gogineni J, Karegar M, et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin gene expression and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(12):E2780–E2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. King GA, Deemer SE, Thompson DL. Relationship between leptin, adiponectin, bone mineral density, and measures of adiposity among pre-menopausal Hispanic and Caucasian women. Endocr Res. 2010;35(3):106–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grundy SM. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2595–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wolfgram PM, Connor EL, Rehm JL, Eickhoff JC, Reeder SB, Allen DB. Ethnic differences in the effects of hepatic fat deposition on insulin resistance in nonobese middle school girls. Obesity. 2014;22(1):243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]