Abstract

Cryptosporidium is one of the most common zoonotic waterborne parasitic diseases worldwide and represents a major public health concern of water utilities in developed nations. As animals in catchments can shed human-infectious Cryptosporidium oocysts, determining the potential role of animals in dissemination of zoonotic Cryptosporidium to drinking water sources is crucial. In the present study, a total of 952 animal faecal samples from four dominant species (kangaroos, rabbits, cattle and sheep) inhabiting Sydney’s drinking water catchments were screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium using a quantitative PCR (qPCR) and positives sequenced at multiple loci. Cryptosporidium species were detected in 3.6% (21/576) of kangaroos, 7.0% (10/142) of cattle, 2.3% (3/128) of sheep and 13.2% (14/106) of rabbit samples screened. Sequence analysis of a region of the 18S rRNA locus identified C. macropodum and C. hominis in 4 and 17 isolates from kangaroos respectively, C. hominis and C. parvum in 6 and 4 isolates respectively each from cattle, C. ubiquitum in 3 isolates from sheep and C. cuniculus in 14 isolates from rabbits. All the Cryptosporidium species identified were zoonotic species with the exception of C. macropodum. Subtyping using the 5’ half of gp60 identified C. hominis IbA10G2 (n = 12) and IdA15G1 (n = 2) in kangaroo faecal samples; C. hominis IbA10G2 (n = 4) and C. parvum IIaA18G3R1 (n = 4) in cattle faecal samples, C. ubiquitum subtype XIIa (n = 1) in sheep and C. cuniculus VbA23 (n = 9) in rabbits. Additional analysis of a subset of samples using primers targeting conserved regions of the MIC1 gene and the 3’ end of gp60 suggests that the C. hominis detected in these animals represent substantial variants that failed to amplify as expected. The significance of this finding requires further investigation but might be reflective of the ability of this C. hominis variant to infect animals. The finding of zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in these animals may have important implications for the management of drinking water catchments to minimize risk to public health.

Introduction

Cryptosporidium is one of the most prevalent waterborne parasitic infections [1] and represents a public health concern of water utilities in developed countries, including Australia. Currently, 31 Cryptosporidium species have been recognised based on biological and molecular characteristics including two recently described species; C. proliferans and C. avium [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Of these, C. parvum and C. hominis have been responsible for all waterborne outbreaks typed to date, with the exception of a single outbreak in the UK caused by C. cuniculus [7, 8, 9].

In Australia, marsupials, rabbits, sheep and cattle are the dominant animals inhabiting drinking water catchments and can contribute large volumes of manure to water sources [10]. Therefore, it is important to understand the potential contribution from these animals in terms of Cryptosporidium oocyst loads into surface water. A number of genotyping studies have been conducted on animals in Australian water catchments to date and have reported a range of species including C. parvum, C. hominis, C. cuniculus, C. ubiquitum, C. bovis, C. ryanae, C. canis, C. macropodum, C. fayeri, C. xiaoi, C. scrofarum, and C. andersoni [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. To date, in humans in Australia, C. hominis, C. parvum, C. meleagridis, C. fayeri, C. andersoni, C. bovis, C. cuniculus, a novel Cryptosporidium species most closely related to C. wrairi and the Cryptosporidium mink genotype have been reported [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]. The aim of the present study was to use molecular tools to identify the Cryptosporidium sp. infecting the kangaroos, rabbits, cattle and sheep population inhabiting Sydney’s drinking water catchments and so better understand the potential health risks they pose.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection and processing

Animal faecal samples were collected by WaterNSW staff from watersheds within the WaterNSW area of operations. Sampling was carried out either on land owned by WaterNSW or on private land owned by farmers who gave permission to WaterNSW staff to conduct this study on their property. To minimize cross-contamination and avoid re-sampling the same animals, animals were observed defecating and then samples were collected randomly from freshly deposited faces from the ground, using a scrapper to expose and scoop from the center of the scat pile. Samples were collected on a monthly interval over an 18 months period (July, 2013 to February, 2015) into individual 75 ml faecal collection pots, and stored at 4°C until required (no animal was sacrificed). As faecal samples were collected from the ground and not per rectum, animal ethics approval was not required. Instead, an animal cadaver/tissue notification covering all the samples collected was supplied to the Murdoch University Animal Ethics Committee. The animal sources of the faecal samples were confirmed by watching the host defecate prior to collection and also with the aid of a scat and tracking manual published for Australian animals [43]. Faecal samples were collected from two previously identified hotspot zones from eastern grey kangaroos (Macropus giganteus) (n = 576), cattle (n = 142), sheep (n = 128) and rabbits (n = 106). This study did not involve collecting samples from endangered or protected animal species. Samples were shipped to Murdoch University and stored at 4°C until required.

Enumeration of Cryptosporidium oocysts in faecal samples

Enumeration of Cryptosporidium oocysts by microscopy was conducted in duplicate for a subset of samples (n = 8) by Australian Laboratory Services (Scoresby, Vic). To quantify recovery efficiency, each individual faecal composite or homogenate was seeded with ColorSeed (Biotechnology Frontiers Ltd. [BTF], Sydney, Australia). Cryptosporidium oocysts were purified from faecal samples using immunomagnetic separation (IMS) employing the Dynal GC Combo kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) as described by Cox et al., (2005) [44]. Oocysts were stained with Easystain and 4’,6’,-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 0.8 μg.ml-1) (Biotechnology Frontiers Ltd. [BTF], Sydney, Australia) and examined with an Axioskop epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany) using filter set 09 (blue light excitation) for Easystain (BTF), filter set 02 (UV light excitation) for DAPI staining, and filter set 15 (green light excitation) for ColorSeed (BTF). The identification criteria described in U.S. EPA method 1623 [45] were used for Easystain-labeled and DAPI-stained objects.

DNA isolation

Genomic DNA was extracted from 250mg of each faecal sample using a Power Soil DNA Kit (MO BIO, Carlsbad, California). A negative control (no faecal sample) was used in each extraction group.

PCR amplification of the 18S rRNA gene

All samples were screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium at the 18S rRNA locus using a quantitative PCR (qPCR) previously described [46, 47]. qPCR standards were Cryptosporidium oocysts (purified and haemocytometer counted), diluted to a concentration of 10,000 oocysts/μl. DNA was extracted from this stock using a Powersoil DNA extraction kit (MO BIO, Carlsbad, California, USA). The 10,000 oocyst/μl DNA stock was then serially diluted to create oocyst DNA concentrations equivalent to 1000, 100, 10, 1 oocysts/μl DNA respectively to be used for standard curve generation using Rotor-Gene 6.0.14 software. Absolute numbers of Cryptosporidium oocysts in these standards were determined using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) at the 18S locus using the same primer set and these ddPCR calibrated standards were used for qPCR as previously described [47]. Each 10 μl PCR mixture contained 1x Go Taq PCR buffer (KAPA Biosystems), 3.75 mM MgCl2, 400 μM of each dNTP, 0.5 μM 18SiF primer, 0.5 μM 18SiR primer, 0.2 μM probe and 1U/reaction Kapa DNA polymerase (KAPA Biosystems). The PCR cycling conditions consisted of one pre-melt cycle at 95°C for 6 min and then 50 cycles of 94°C for 20 sec and 60°C for 90 sec.

Samples that were positive by qPCR were amplified at the 18S locus using primers which produced a 611 bp product (Table 1) as previously described [48] with minor modifications; the annealing temperature used in the present study was 57°C for 30 sec and the number of cycles was increased from 39 to 47 cycles for both primary and secondary reactions. PCR contamination controls were used including negative controls and separation of preparation and amplification areas. A spike analysis (addition of 0.5 μL of positive control DNA into each sample) at the 18S locus by qPCR, was conducted on randomly selected negative samples from each group of DNA extractions to determine if negative results were due to PCR inhibition, by comparing the Ct of the spike and the positive control (both with same amount of DNA).

Table 1. List of primers used in this study to amplify Cryptosporidium species at 18S, lectin (Clec), gp60, lib13 and MIC1 gene loci.

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18S | 5′ ACCTATCAGCTTTAGACGGTAGGGTAT 3′ | 5′ TTCTCATAAGGTGCTGAAGGAGTAAGG 3′ | [48] |

| 5′ ACAGGGAGGTAGTGA CAAGAAATAACA 3′ | 5′ AAGGAGTAAGGAACAACCTCCA 3′ | ||

| lectin (Clec) | 5′ TCAACTAACGAAGGAGGGGA 3’ | 5′ GTGGTGTAGAATCGTGGCCT 3′ | Present Study |

| 5′ CCAACATACCATCCTTTGG 3′ | 5′ GTGGTGTAGAATCGTGGCCT 3′ | ||

| gp60 | 5′ ATAGTCTCGCTGTATTC 3′ | 5′ GCAGAGGAACCAGCATC 3′ | [49, 50] |

| 5′ TCCGCTGTATTCTCAGCC 3′ | 5′ GAGATATATCTTGGTGCG 3′ | ||

| 18S | 5′ TTCTAGAGCTAATACATGCG 3′ | 5′ CCCATTTCCTTCGAAACAGGA 3′ | [51, 52] |

| 5′ CCCATTTCCTTCGAAACAGGA 3′ | 5′ CTCATAAGGTGCTGAAGGAGTA 3′ | ||

| gp60 | 5′ ATAGTCTCCGCTGTATTC 3′ | 5′ GGAAGGAACGATGTATCT 3′ | [52, 53] |

| 5′ GGAAGGGTTGTATTTATTAGATAAAG 3′ | 5′ GCAGAG GAA CCAGCAT 3′ | ||

| lib13 | 5′ TCCTTGAAATGAATATTTGTGACTCG 3′ | 5′ AAATGTGGTAGTTGCGGTTGAAA 3′ | [54] |

| Probe: VIC-CTTACTTCGTGGCGGCGT MGB-NFQ | |||

| MIC1 | 5′ TGCAGCACAAACAGTAGATGTG 3′ | 5′ ATAAGGATCTGCCAAAGGAACA 3′ | [52] |

| 5′ ACCGGAATTGATGAGAAATCTG 3′ | 5′ CATTGAAAGGTTGACCTGGAT 3′ |

PCR amplification of the lectin (Clec) gene

Samples that were typed as C. parvum, C. hominis and C. cuniculus at the 18S locus were also typed using sequence analysis at a unique Cryptosporidium specific gene (Clec) that codes for a novel mucin-like glycoprotein that contains a C-type lectin domain [55, 56]. Hemi-nested primers were designed for this study using MacVector 12.6 (http://www.macvector.com). The external primers Lectin F1 5’ TCAACTAACGAAGGAGGGGA 3’ and Lectin R1 5’ GTGGTGTAGAATCGTGGCCT 3’ produced a fragment size of 668 bp for C. hominis and 656 bp for C. parvum. The secondary reaction consisted of primers, Lectin F2 5’ CCAACATACCATCCTTTGG 3’ and Lectin R1 5’ GTGGTGTAGAATCGTGGCCT 3’ (Table 1), which produced a fragment of 518 bp for C. hominis, 506 bp for C. parvum and 498 bp for C. cuniculus. The cycling conditions for the primary amplification was 94°C for 3 min, followed by 94°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min for 40 cycles, plus 5 min at 72°C for the final extension. The same cycling conditions were used for the secondary PCR, with the exception that the number of cycles was increased to 47 cycles. The 25 μl PCR mixture consisted of 1 μl of DNA, 1x Go Taq PCR buffer (KAPA Biosystems), 200 μM of each dNTP (Promega, Australia), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.4 μM of each primer, 0.5 units of Kapa DNA polymerase (KAPA Biosystems). The specificity of this locus for Cryptosporidium has been previously confirmed [41]. Enumeration of Cryptosporidium oocysts by qPCR was conducted using a specific C. hominis and C. parvum assay targeting the Clec gene as previously described [41].

PCR amplification of the gp60 gene

Samples that were typed as C. hominis, C. parvum, C. cuniculus and C. ubiquitum at the 18S locus were subtyped at the 60 kDa glycoprotein (gp60) locus using nested PCR as previously described (Table 1) [57, 49 50, 58].

Sequence analysis and phylogenetic analysis

The amplified DNA from secondary PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis and purified for sequencing using an in house filter tip method [41]. Purified PCR products from all three loci, were sequenced independently using an ABI Prism™ Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) according to the manufacturer’s instructions at 57°C, 58°C and 54°C annealing temperature for the 18S rRNA, lectin and gp60 loci, respectively. Sanger sequencing chromatogram files were imported into Geneious Pro 8.1.6 [59], edited, analysed and aligned with reference sequences from GenBank using ClustalW (http://www.clustalw.genome.jp). Distance, parsimony and maximum likelihood trees were constructed using MEGA version 7 [60].

Independent confirmation by the Australian Water Quality Centre (AWQC)

A total of eight blinded faecal samples consisting of seven C. hominis positives and one Cryptosporidium negative were sent to the Australian Water Quality Centre (AWQC) for independent analysis. DNA was extracted using a QIAamp DNA Mini extraction kit (Qiagen, Australia). Samples were screened using primers targeting the 18S rRNA locus (Xiao et al., 2000 as modified by Webber at al., 2014) [51, 52], gp60 using producing an approx. 871 bp secondary product (Alves et al., 2003 as modified by Webber at al., 2014) [53, 52] and an approx. 400 bp primary product [50] as well as the lib13 [54] and MIC1 gene loci [52] as previously described (Table 1). PCRs were conducted on a RotorGene 6000 HRM (Qiagen) or LightCycler 96 (Roche) and amplification of the correct product was determined by DNA melting curve analysis [52]. Amplicons with atypical DNA melting profiles were further characterized by capillary electrophoresis using a DNA 1000 chip on a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplicons from all positive PCRs were purified using a Qiagen PCR purification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions and submitted to the Australian Genome Research Facility for DNA sequencing using BigDye3 chemistry on an Applied Biosystems AB3730xl capillary DNA sequencer. Sequences were analyzed using Geneious Pro 6.1.8 (Biomatters).

PCR amplification of open reading frames flanking gp60 and MIC1

Open reading frames flanking both ends of gp60 and MIC1 in the C. parvum genome were used in BLAST searches (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to obtain homologous C. hominis sequences. Alignments of the C. parvum and C. hominis open reading frame pairs were constructed using Geneious Pro 6.1.8 (Biomatters). Conserved primers were designed for each alignment using the default settings and a target amplicon size of approximately 400 bp. The resulting primers (Table 2) were subjected to BLAST searches to verify specificity.

Table 2. List of primers designed in the present study to amplify regions flanking the 5’ and 3’ ends of MIC1 and gp60.

| Gene | Flanking openreading frame | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Product size (C. parvum and C. hominis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC1 | cgd6_770 Chro. 60100(3’ end)hypothetical proteinCDS | 5’TGCGGTTGTATGACACCATCA 3’ | 5’TCTCTGGTGTTTGGCCTGAC 3’ | 511 |

| cgd6_810 Chro. 60105(5’ end)BRCT | 5’AGACACCAAGATGGAAAAGGCA 3’ | 5’GGGAAGACCTTTTGATATTGCCC 3’ | 467 | |

| gp60 | cgd6_1070 Chro. 60137(3’ end)conservedhypothetical protein | 5’AGCAAGACCGCAACTCAAGT 3’ | 5’CCCATAGTGCCCAGCTTGAA 3’ | 430 |

| cgd6_1090 Chro. 60141(5’ end) hsp40 | 5’TATTTGGAGGTGGGGCCAAG 3’ | 5’AAAACGGGTTTAGGGGTGGT 3’ | 367 |

Each 25 μl qPCR reaction contained 0.5 x GoTaq PCR Buffer (Promega), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP, 3.3 μM SYTO 9, 100 ng GP32, 0.5 μM forward primer, 0.5 μM reverse primer, 1 unit Promega GoTaq HS, and 2 μl of DNA extract. The qPCR was performed on a Light Cycler96 (Roche), and cycling conditions consisted of one pre-melt cycle at 95°C for 6 min and then 40 cycles of 94°C for 45 sec, 60°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 60 sec. High-resolution DNA melting curve analysis was conducted from 65°C to 97°C using an acquisition rate of 25 reads /°C. Blastocystis hominis DNA was used as a negative control and nuclease free water was used as a no template control. Positive controls included C. parvum Iowa 2a (BTF, Sydney, Australia) and C. hominis IbA10G2 (kindly provided by Ika Sari). Amplicons were sized by capillary electrophoresis using a DNA 1000 chip on a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

The prevalence of Cryptosporidium in faecal samples collected from each host species was expressed as the percentage of samples positive by qPCR, with 95% confidence intervals calculated assuming a binomial distribution, using the software Quantitative Parasitology 3.0 [61]. Linear coefficients of determination (R2) and Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (Spearman's rho) were used for the analysis of agreement (correlation) between oocyst numbers per gram of faeces determined by qPCR calibrated with ddPCR standards and enumeration of Cryptosporidium oocysts by microscopy (IMS) using SPSS 21.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA).

Results

Prevalence of Cryptosporidium in faecal samples collected from various hosts

The overall PCR prevalence of Cryptosporidium species in 952 faecal samples collected from four different host species was 5% (48/952) (Table 3). Cryptosporidium species were detected in 3.6% (21/576) of the kangaroo faecal samples, 7.0% (10/142) of cattle faeces, 2.3% (3/128) of sheep faeces and 13.2% (14/106) of rabbit faecal samples based on qPCR and sequence analysis of the 18S rRNA locus (Table 3).

Table 3. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium species in faecal samples collected from four different host species in Sydney water catchments*.

95% confidence intervals are given in parenthesis.

| Host species | Number of samples | Number of positives | Prevalence% | Species and subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern grey kangaroo | 576 | 21 | 3.6 (95% CI: 2.3–5.5) | C. hominis (n = 17)**,IbA10G2 (n = 12),IdA15G1 (n = 2),C. macropodum (n = 4) |

| Cattle | 142 | 10 | 7 (95% CI: 3.4–12.6) | C. hominis (n = 6)**,IbA10G2 (n = 4),C. parvum (n = 4),IIaA18G3R1 (n = 4) |

| Sheep | 128 | 3 | 2.3 (95% CI: 0.5–6.7) | C. ubiquitum (n = 3)**,XIIa (1) |

| Rabbit | 106 | 14 | 13.2 (95% CI: 7.4–21.2) | C. cuniculus (n = 14)**,VbA 23 (n = 9) |

| Total | 952 | 48 | 5 (95% CI: 3.7–6.6) |

* Based on PCR amplification and sequencing at the 18S rRNA gene, with subtyping based on DNA sequence analysis of a 400 bp amplicon from the 5’ end of the gp60 locus.

** Not all positive samples were successfully typed.

Cryptosporidium species detected in various hosts

Sequencing of secondary PCR amplicons at the 18S rRNA locus identified four of the 21 positive isolates from kangaroo faecal samples as C. macropodum, while the other 17 isolates were identified as C. hominis (100% similarity for 550bp) (Table 4). Of the ten positives detected in cattle faecal samples, six were C. hominis and four were C. parvum (Table 4). The three sheep positive samples were identified as C. ubiquitum and all fourteen positives detected in rabbit faecal samples were C. cuniculus (Table 4).

Table 4. Species and subtypes of Cryptosporidium identified in faecal samples from various hosts (and their GPS co-ordinates) at the 18S and gp60 loci.

| Host species | Southing | Easting | 18S locus | gp60 locus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern grey kangaroo 1 | -34.18861 | 150.2918 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 2 | -34.203794 | 150.284394 | C. macropodum | - |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 3 | -34.20207 | 150.2742 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 4 | -34.193631 | 150.273387 | C. macropodum | - |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 5 | -34.188607 | 150.291818 | C. macropodum | - |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 6 | -34.20458 | 150.2881 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 7 | -34.61547 | 150.59756 | C. hominis | no amplification |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 8 | -34.23796 | 150.2598 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 9 | N/A | N/A | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 10 | N/A | N/A | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 11 | N/A | N/A | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 12 | N/A | N/A | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 13 | -34.61686 | 150.68794 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 14 | -34.63269 | 150.619 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 15 | -34.63269 | 150.61897 | C. hominis | no amplification |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 16 | -34.61422 | 150.59331 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA15G1 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 17 | -34.61415 | 150.59376 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 18 | -34.61686 | 150.68794 | C. hominis | no amplification |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 19 | -31.60846 | 150.60819 | C. macropodum | - |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 20 | -34.61472 | 150.68475 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 21 | -34.61472 | 150.68475 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA15G1 |

| Cattle 1 | -34.61278 | 150.585 | C. hominis | no amplification |

| Cattle 2 | -34.60429 | 150.60170 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Cattle 3 | -34.61283 | 150.58514 | C. hominis | no amplification |

| Cattle 4 | -34.60429 | 150.60170 | C. parvum | C. parvum IIaA18G3R1 |

| Cattle 5 | -34.60642 | 150.60126 | C. parvum | C. parvum IIaA18G3R1 |

| Cattle 6 | -34.61373 | 150.5876 | C. parvum | C. parvum IIaA18G3R1 |

| Cattle 7 | -34.61373 | 150.5876 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Cattle 8 | -34.6195 | 150.5242 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Cattle 9 | -34.60429 | 150.60170 | C. hominis | C. hominis IbA10G2 |

| Cattle 10 | -34.63269 | 150.619 | C. parvum | C. parvum IIaA18G3R1 |

| Sheep 1 | -34.61556 | 150.68353 | C. ubiquitum | no amplification |

| Sheep 2 | -34.61556 | 150.68353 | C. ubiquitum | no amplification |

| Sheep 3 | -34.61743 | 150.68674 | C. ubiquitum | C. ubiquitum XIIa |

| Rabbit 1 | -34.61954 | 150.62169 | C. cuniculus | no amplification |

| Rabbit 2 | -34.61959 | 150.62172 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

| Rabbit 3 | -34.61937 | 150.62178 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

| Rabbit 4 | -34.61479 | 150.68492 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

| Rabbit 5 | -34.61954 | 150.62169 | C. cuniculus | no amplification |

| Rabbit 6 | -34.6195 | 150.52415 | C. cuniculus | no amplification |

| Rabbit 7 | -34.61937 | 150.62178 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

| Rabbit 8 | -34.61283 | 150.58514 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

| Rabbit 9 | -34.61556 | 150.68353 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

| Rabbit 10 | -34.61278 | 150.585 | C. cuniculus | no amplification |

| Rabbit 11 | -34.61479 | 150.68492 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

| Rabbit 12 | -34.60429 | 150.60170 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

| Rabbit 13 | -34.18951 | 150.2885 | C. cuniculus | no amplification |

| Rabbit 14 | -34.6327 | 150.619 | C. cuniculus | C. cuniculus VbA23 |

Sequence analysis at the lectin (Clec) locus was consistent with 18S gene results. Eleven of 17 C. hominis isolates from kangaroos were successfully amplified and confirmed as C. hominis sequences. Eight of the 14 positives from rabbits successfully amplified at this locus and were identified as C. cuniculus. Four of six C. hominis and all four C. parvum isolates from cattle were also confirmed at this locus.

Sequences at the gp60 locus were obtained for 14 kangaroo and four cattle isolates that were typed as C. hominis at the 18S rRNA locus. These samples failed to amplify at gp60 using the primers of Strong et al., (2000) or Alves et al., (2003) [57, 53], which amplify an approx. 832 bp fragment, but were successfully amplified using the nested primers by Zhou et al., (2003) [53], which amplify a 400 bp product. In approx. 50% of samples, the primary reaction did not produce a visible band by gel electrophoresis but a band of the correct size was visible for the secondary PCR, which was then confirmed by sequencing.

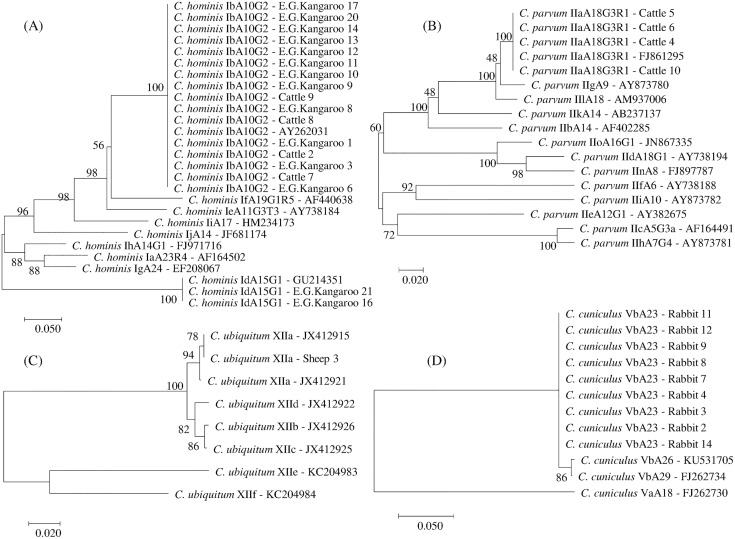

The C. hominis subtypes IbA10G2 and IdA15G1 were identified in 12 and 2 kangaroo samples respectively and the IbA10G2 subtype was also identified in four cattle samples (Table 4 and Fig 1A). The four C. parvum isolates from cattle were identified as subtype IIaA18G3R1 and the C. cuniculus isolates were subtyped as VbA23 (n = 9) (Table 4 and Fig 1B and 1D). Of the three C. ubiquitum positive isolates at 18S locus, only one isolate was successfully subtyped and identified as C. ubiquitum subtype XIIa (Table 4 and Fig 1C). Nucleotide sequences reported in this paper are available in the GenBank database under accession numbers; KX375346, KX375347, KX375348, KX375349, KX375350, KX375351, KX375352, KX375353, KX375354, KX375355.

Fig 1. Phylogenetic relationships of Cryptosporidium subtypes inferred from Neighbor-Joining (NJ) analysis of Kimura’s distances calculated from pair-wise comparisons of gp60 sequences.

(A) Relationships among C. hominis subtypes. (B) Relationships among C. parvum subtypes. (C) Relationships between C. ubiquitum subtypes. (D) Relationships between C. cuniculus subtypes. Percentage support (>50%) from 1000 pseudoreplicates from NJ analyses is indicated at the left of the supported node.

Independent confirmation by the Australian Water Quality Centre (AWQC)

Blind independent analysis conducted by AWQC using the 18S rRNA nested PCR of Xiao et al., (2000) [51] identified C. hominis in six samples, corresponding with the six positive samples from kangaroos, and failed to detect Cryptosporidium in the other two samples, one of which corresponded with the negative sample. Amplification of a region of gp60 using the protocol described by Alves et al. [53] failed to produce an amplicon for either the primary or secondary reactions. Amplification of gp60 using the protocol described by Zhou et al., (2003) [50], failed to amplify the correct-sized product for the primary PCR but produced amplicons of the correct size for the secondary PCR for the six positive samples, which when sequenced were confirmed as C. hominis subtype IbA10G2. Amplification at the lib13 locus was also successful for the six positive samples, which were confirmed as C. hominis. Amplification at the MIC1 locus failed to produce any amplicons. The gp60 and MIC1 amplification failures were further investigated using PCR assays designed to target open reading frames (ORFs) flanking these two loci. All four primer sets produced strong amplification of the correctly sized fragments for the C. parvum and C. hominis control DNA. The cgd6-1070 ORF (located downstream of gp60 in C. parvum), and cgd6-810 (upstream of MIC1), both amplified from four of the six samples identified as C. hominis. In the case of the other 2 ORFs, weak amplification was observed for one sample for cgd6-1090 (upstream of gp60) and for two samples for cgd6-770 (downstream of MIC1). While only single bands were observed for the C. parvum and C. hominis controls, most of the faecal sample extracts produced multiple bands.

Enumeration of Cryptosporidium oocysts in faecal samples

Oocyst numbers per gram of faeces for all PCR positive samples were determined using qPCR at the Clec locus for 18 C. hominis and 4 C. parvum positives and for a subset of samples (n = 8) using microscopy (Table 5). For the 8 samples for which both microscopy and qPCR data were available, there was poor correlation between the two methods (R2 ≈ 0.0095 and ρ (rho) = 0.2026) (Table 5). Based on qPCR, the highest numbers of oocysts was detected in Eastern grey kangaroo isolate 12 (16,890 oocysts/g-1), which was identified as C. hominis subtype IbA10G2. No oocysts (<2g-1) were detected by microscopy in this sample.

Table 5. Cryptosporidium oocyst numbers in positive samples per gram of faeces (g-1) determined using microscopy and qPCR.

Note: microscopy data was only available for 12 samples.

| Host species | Cryptosporidium species (18S) | Oocyst numbers/g-1 microscopy | % Oocyst recovery | Oocyst numbers/g-1 qPCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern grey kangaroo 1 | C. hominis | 210 | 54 | 11,337 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 3 | C. hominis | 11,076 | 78 | 5,458 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 6 | C. hominis | <2 | 61 | 9,528 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 8 | C. hominis | <2 | 45 | 262 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 9 | C. hominis | <2 | 74 | 648 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 10 | C. hominis | <2 | 51 | 8,735 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 11 | C. hominis | <2 | 67 | 131 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 12 | C. hominis | <2 | 60 | 16,890 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 13 | C. hominis | - | - | 26 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 14 | C. hominis | - | - | 5,458 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 16 | C. hominis | - | - | 7,570 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 17 | C. hominis | - | - | 9,626 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 20 | C. hominis | - | - | 8,735 |

| Eastern grey kangaroo 21 | C. hominis | - | - | 173 |

| Cattle 2 | C. hominis | - | - | 144 |

| Cattle 4 | C. parvum | - | - | 936 |

| Cattle 5 | C. parvum | - | - | 1,819 |

| Cattle 6 | C. parvum | - | - | 2,197 |

| Cattle 7 | C. hominis | - | - | 4,205 |

| Cattle 8 | C. hominis | - | - | 10,827 |

| Cattle 9 | C. hominis | - | - | 15,804 |

| Cattle 10 | C. parvum | - | - | 1,190 |

Discussion

The present study described the prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium species in faecal samples collected from kangaroo, cattle, sheep and rabbit faecal samples from Sydney’s drinking water catchments. The overall prevalence of Cryptosporidium species in the faecal samples collected from four animal hosts was 5% and was 3.6% in kangaroos, 7% in cattle, 2.3% in sheep and 13.2% in rabbits. Overall, the prevalence of infection with Cryptosporidium was generally lower than that reported previously in Sydney catchments; 25.8% [44] 6.7% [62] and 8.5% [16] and Western Australian catchments; 6.7% [13]. In the study by Ng et al., (2011b) [16], the prevalence in eastern grey kangaroos was much higher (16.9%−27/160) than the 3.6% prevalence in kangaroo faecal samples in the present study. The overall prevalence of Cryptosporidium species in faecal samples collected from different species in the present study was similar to the 2.8% (56/2,009) prevalence identified in faecal samples from animals in Melbourne water catchments [20]. The lower prevalence in the present study and the Melbourne study may be a consequence of testing a greater numbers of samples, seasonal and/or yearly variation in prevalence and/or proximity to agricultural land.

Based on sequence analysis using the 18S rRNA locus, a total of five Cryptosporidium species were identified; C. macropodum (n = 4), C. hominis (n = 23), C. parvum (n = 4), C. ubiquitum (n = 3) and C. cuniculus (n = 14). The prospect of livestock and wildlife being reservoirs for C. hominis has human-health implications, so to verify this finding, a subset of faecal samples was subjected to blinded independent analysis. This additional testing initially identified C. hominis following sequence analysis of a large fragment of the 18S rRNA gene amplified using the Xiao et al., (2000) [51] nested PCR. It is noteworthy that the Xiao outer 18S PCR produced a clear amplification signal (threshold cycles between 24 and 29 for positive samples), suggesting the presence of reasonable numbers of oocysts with no evidence of PCR inhibition for this relatively large amplicon (approx. 1.2 kilobases). The lib13 Taqman assay also identified C. hominis in these same samples. However, amplification of gp60 using the Alves et al., (2003) [53] nested PCR failed to amplify any Cryptosporidium, either as a nested PCR or by direct amplification using the inner primer set. Application of the Zhou et al., (2003) [53] outer gp60 primers (which are equivalent to the pairing of the Alves outer forward and inner reverse primers) also appeared to be unsuccessful (only four samples produced a band close to the expected size), but the Zhou gp60 inner PCR amplified the correctly sized amplicon, which was confirmed to be C. hominis IbA10G2.

The failure to amplify gp60 using the Alves et al., (2003) and Strong et al., (2000) [57, 53] assays was unexpected, especially considering the high degree of conservation for the primer binding sites across the C. parvum and C. hominis gp60 subtypes and the successful amplification of the large 18S rRNA gene fragment, which demonstrates that the DNA quantity and quality was sufficient for amplification within the first round of PCR. The lack of amplification at other loci is unlikely to be due to PCR inhibition, as spike analysis indicated no inhibition. To investigate this further, a published PCR assay targeting the MIC1 locus from both C. parvum and C. hominis [52] was also tested and failed to amplify the expected fragment from these samples. The MIC1 gene encodes a thrombospondin-like domain-containing protein, which is secreted in sporozoites prior to host cell attachment and localized to the apical complex after microneme discharge [63]. As secreted proteins often play a critical role in determining virulence and host specificity in host-pathogen relationships, it has been hypothesized that MIC1 may play a role in the differences in host range observed between C. parvum and C. hominis [52]. Previous analysis of the CryptoDB has identified that both the gp60 and MIC1 loci are on chromosome 6 and in close proximity (≈60 kb) [52], and it has previously been reported that these two genes are genetically linked [64]. Given that 3 different gp60 reverse primers appear to have failed, as well as failure of at least one of the MIC1 primers, it would require the occurrence of multiple individual single nucleotide polymorphisms for the results to be accounted for by point mutations. Alternatively, a truncation or rearrangement on chromosome 6 affecting the 3’ end of gp60 and MIC1 could affect these PCR assays. To test for any deletions affecting these loci, PCR assays were developed targeting flanking ORFs. The PCR assays targeting two ORFs in the region between MIC1 and gp60 (based on the C. parvum chromosome 6 map) were positive for some of the samples tested, suggesting that a wholesale deletion is not the cause for the failure to amplify MIC1 or the entire gp60. The other two PCR assays produced equivocal results in the samples, although they yielded strong amplification in the positive controls. The variable sample results may have been due to a combination of the low amount of Cryptosporidium DNA present and non-specific amplification from other DNA in the sample extracts. The latter is likely, considering that the positive controls produced a single amplicon, whereas most of the sample extracts yielded multiple fragments of different sizes.

Sequencing of chromosome 6 or the entire genome of this variant C. hominis is required to determine the underlying cause for the failure to amplify MIC1 or the larger gp60 region. Considering the role of gp60 in host cell adhesion and the hypothesized role of MIC1 in infection, it is possible that changes or loss of key genes involved in host specificity could explain the success of this particular variant of C. hominis in infecting hosts other than humans. If the function of these genes has been altered to better support infection in non-human hosts, then the infectivity of this variant in humans needs to be re-evaluated.

Of the detected species, all but C. macropodum have been reported to cause infection in humans at varying frequencies [7, 10]. Cryptosporidium hominis and C. parvum are responsible for the majority of human infections worldwide [7, 6]. In the present study, the prevalence of the variant C. hominis in kangaroo and cattle faecal samples was 2.9% (95% CI: 1.7%-4.7%) and 4.2% (95% CI: 1.6%-9%) respectively, and the prevalence of C. parvum in cattle faecal samples was 2.8% (95% CI: 0.8%-7.1%). Both of these parasites have been linked to numerous waterborne outbreaks around the world [7, 1] and although this prevalence is relatively low, both these host species represent a risk of waterborne transmission to humans. A number of previous studies have identified C. hominis/C. parvum-like isolates at the 18S rRNA locus in marsupials including bandicoots (Isoodon obesulus), brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula), eastern grey kangaroos (Macropus giganteus) and brush-tailed rock-wallabies (Petrogale penicillata) [65, 66, 67]. However, in those studies, despite efforts, the identification of C. hominis/C. parvum could not be confirmed at other loci. This may be due to low numbers of oocysts and the multi-copy nature of the 18S rRNA gene, which provides better sensitivity at this locus. Alternatively, failure to confirm identity in these other studies could be due the presence of variants with substantial differences in the diagnostic loci used, causing those PCR assays to fail. Such is the case in the present study, which for the first time has identified a novel C. hominis in kangaroo faecal samples based on analysis of multiple loci (18S rRNA, Clec, MIC1, lib13 and gp60).

Cryptosporidium cuniculus, the most prevalent species detected here (13.2%), has been previously identified in rabbits, humans and a kangaroo in Australia [14, 20, Sari et al., 2013 unpublished—KF279538, 21]. It was implicated in a waterborne outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in humans in England in 2008 [8, 9] and has been linked to a number of sporadic human cases across the UK [68, 69], Nigeria [70] and France [71]. Cryptosporidium ubiquitum was detected in three sheep samples and is a common human pathogen [7], but has not been identified in Australia in the limited typing of Australian human Cryptosporidium isolates that has been conducted to date [10], however it has been identified in surface waters in Australia (Monis et al., unpublished).

Subtyping at the gp60 locus identified the C. hominis subtype IbA10G2 in twelve kangaroo and four cattle faecal samples. This is a dominant subtype responsible for C. hominis-associated outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis in the United States, Europe and Australia [7, 72, 73, 74]. Cryptosporidium hominis has previously been reported in cattle in New Zealand [75], Scotland [76], India [77] and Korea [78]. Subtyping at the gp60 locus identified IbA10G2 [76, 75], and IdA15G1 [77]. It has been suggested that the IbA10G2 infects cattle naturally in particular circumstances and thus could act as a zoonotic infection source in some instances [76]. Interestingly, the studies that detected IbA10G2 in cattle, used PCR-based assays that only sequenced the 5’ end of gp60, similar to the assay used in this study, so it is possible that these reports also represent detection of a variant C. hominis gp60. This is the first report of the same subtype of C. hominis in kangaroos and cattle in the same catchment. In two kangaroo samples, the C. hominis IdA15G1 subtype was identified. This is also a common C. hominis subtype identified in humans worldwide [28, 79, 80, 81, 74]. The source and human health significance of the novel C. hominis detected in kangaroo and cattle samples in the present study is currently unknown. Environmental pollution from human and domestic animal faeces such as contamination of watersheds due to anthropogenic and agricultural activities conducted in the catchment area, in particular livestock farming, could be a potential source for wildlife infections with C. hominis. However, further studies are required to better understand the involvement of humans and livestock in the epidemiology of zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in wildlife.

The C. parvum subtype IIaA18G3R1 was identified in four cattle samples. IIaA18G3R1 is also a common subtype in both humans and cattle worldwide and has been reported widely in both calves and humans in Australia [10]. Subtyping of the single C. ubiquitum isolate from sheep identified XIIa. To date six subtype families (XIIa to XIIf) have been identified in C. ubiquitum [58]. Of these, XIIa, XIIb, XIIc, and XIId have been found in humans and therefore XIIa is a potentially zoonotic subtype [54] The C. cuniculus subtype identified in the present study was VbA23. Two distinct gp60 subtype families, designated Va and Vb have been identified in C. cuniculus [8]. Most cases described in humans relate to clade Va and the first waterborne outbreak was typed as VaA22 [82, 8]. Previous studies in Australia have identified subtype VbA26 from an Eastern grey kangaroo [42], subtypes VbA23R3 and VbA26R4 [14, 20], VbA22R4, VbA24R3 and VbA25R4 [20] in rabbits and subtype VbA25 [42] and VbA27 (Sari et al., 2013 unpublished—KF279538) in a human patient.

Accurate quantification of Cryptosporidium oocysts in animal faecal deposits on land is important for estimating catchment Cryptosporidium loads. In the present study, oocyst concentration (numbers per gram of faeces—g-1) was also determined for 18 C. hominis and 4 C. parvum positives using qPCR and for a subset of samples (n = 8) by microscopy. qPCR quantitation was conducted at the Clec locus rather than the 18S rRNA locus as the former is unique to Cryptosporidium and therefore more specific than the available 18S rRNA qPCR assays. There was poor correlation between qPCR and microscopy for the 8 samples for which data from both methods were available, with qPCR detecting higher numbers of oocysts than microscopy with the exception of one sample (Eastern grey kangaroo 3). Increased sensitivity of qPCR and the estimation of much higher numbers of oocysts in faecal samples by qPCR versus microscopy has been previously reported [83]. A major limitation of qPCR is that the quantitative data generated are only as accurate as the standards used. A study which compared droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) (which provides absolute quantitation without the need for calibration curves) with qPCR, reported that qPCR overestimated the oocysts counts compared to ddPCR [47]. In the present study, the discrepancy between qPCR and microscopy could be due to a number of different factors; (1) IMS for microscopy and direct DNA extraction from faeces were conducted on different subsamples of each faecal sample and therefore the numbers of oocysts present in the subsamples may differ, (2) microscopy counts intact oocysts whereas qPCR will detect not only oocysts but also sporozoites that have been released from oocysts, other lifecycle stages and any free DNA, therefore qPCR may produce higher counts than microscopy. In the present study, the mean oocysts g-1 for kangaroos and cattle that were positive for C. hominis was 6,041 (range 26–16,890) and for cattle that were positive for C. parvum was 1535(range 936–2,197) as determined by PCR. By microscopy, oocysts counts were available for kangaroo samples only and the mean was 5,643 (range <0.5–11,076). A previous study in WaterNSW catchments, reported mean Cryptosporidium oocysts g-1 of 40 (range 1–5,988) for adult cattle, 25 for juvenile cattle (range <1–17,467), 23 for adult sheep (range <1–152,474), 49 for juvenile sheep (range <1–641) and 54 for adult kangaroos (range <1–39,423) [84]. The age of the kangaroos and cattle sampled in the present study are unknown, but qPCR quantitation suggests that these were actual infections and not mechanical transmission. However, future studies should include oocyst purification via IMS prior to qPCR for more accurate quantitation. In addition, homogenisation of samples is important when comparing microscopy and qPCR i.e faecal slurries should be made, mixed well and aliquots of that mixture used for both microscopy and qPCR to ensure better consistency between techniques.

It is important to note that of the numbers of oocysts detected in animal faeces in catchments, only a fraction of oocysts may be infectious. For example, a recent study has shown that the infectivity fraction of oocysts within source water samples in South Australian catchments was low (~3.1%) [85]. While it would be expected that oocysts in faecal samples would have much higher infectivity than oocysts in source water, reports suggest that only 50% of oocysts in fresh faeces are infectious, and that temperature and desiccation can rapidly inactivate oocysts in faeces while solar inactivation, predation and temperature will all impact oocyst survival in water [86].

The identification of mostly zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in animals inhabiting Sydney catchments indicates that there is a need to diligently monitor Cryptosporidium in source waters. Such monitoring is also critical, given the resistance of Cryptosporidium oocysts to chlorine [87]. Further studies are essential to confirm the nature of the C. hominis variant detected in this study and to determine if it represents an infection risk for humans.

Conclusions

Of the five Cryptosporidium species identified in this study, four species are of public health significance. The presence of zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in both livestock and wildlife inhabiting drinking water catchments may have implications for management of drinking water sources. Therefore, continued identification of the sources/carriers of human pathogenic strains would be useful to more accurately assess risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Alexander William Gofton for technical assistance during PCR amplification, Frances Brigg and the Western Australia State Agriculture Biotechnology Centre for Sanger sequencing.

Data Availability

Sanger sequencing results for this study and NCBI Genbank accession numbers have been provided: KX375346, KX375347, KX375348, KX375349, KX375350, KX375351, KX375352, KX375353, KX375354, KX375355.

Funding Statement

This study was financially supported by an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant number LP130100035. WaterNSW are an Industry Partner on this ARC Linkage grant and the funder contributed financial support in the form of salaries for authors [AP] and laboratory work. WaterNSW played a significant role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of WaterNSW authors [AB] are articulated in the 'author contributions' section.

References

- 1.Baldursson S, Karanis P. Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasites: review of worldwide outbreaks—an update 2004–2010. Water Res. 2011;45(20):6603–6614. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan U, Hijjawi N. New developments in Cryptosporidium research. Int J Parasitol. 2015;45(6):367–373. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Pereira M, Larsen R, Xiao C, Phillips R, Striby K, et al. Cryptosporidium rubeyi n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in multiple Spermophilus ground squirrel species. Int J Parasitol: Parasites Wildl. 2015;4(3):343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kváč M, Havrdová N, Hlásková L, Daňková T, Kanděra J, Ježková J, et al. Cryptosporidium proliferans n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae): Molecular and biological evidence of cryptic species within gastric Cryptosporidium of mammals. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147090 10.1371/journal.pone.0147090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holubová N, Sak B, Horčičková M, Hlásková L, Květoňová D, Menchaca S, et al. Cryptosporidium avium n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in birds. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2241–2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zahedi A, Paparini A, Jian F, Robertson I, Ryan U. Public health significance of zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in wildlife: critical insights into better drinking water management. Int J Parasitol: Parasit Wildl. 2016;5:88–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124(1):80–89. 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalmers RM, Robinson G, Elwin K, Hadfield SJ, Xiao L, Ryan U, et al. Cryptosporidium sp. rabbit genotype, a newly identified human pathogen. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(5): 829–830. 10.3201/eid1505.081419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puleston RL, Mallaghan CM, Modha DE, Hunter PR, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Regan CM, et al. The first recorded outbreak of cryptosporidiosis due to Cryptosporidium cuniculus (formerly rabbit genotype), following a water quality incident. J Water Health. 2014;12(1):41–50. 10.2166/wh.2013.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan U, Power M. Cryptosporidium species in Australian wildlife and domestic animals. Parasitol. 2012;139(13):673–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Power ML, Slade MB, Sangster NC, Veal DA. Genetic characterisation of Cryptosporidium from a wild population of eastern grey kangaroos Macropus giganteus inhabiting a water catchment. Infect Genet Evol. 2004;4(1):59–67. 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cinque K, Stevens MA, Haydon SR, Jex AR, Gasser RB, Campbell BE. Investigating public health impacts of deer in a protected drinking water supply watershed. Water Sci Technol. 2008;58(1):127–132. 10.2166/wst.2008.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy S, Ng J, Gordon C, Miller R, Wyber A, Ryan UM. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia species in animals in irrigation catchments in the southwest of Australia. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118(4):596–599. 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolan MJ, Jex AR, Haydon SR, Stevens MA, Gasser RB. Molecular detection of Cryptosporidium cuniculus in rabbits in Australia. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10(8):1179–1187. 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng J, Yang R, McCarthy S, Gordon C, Hijjawi N, Ryan U. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in pre-weaned calves in Western Australia and New South Wales. Vet Parasitol. 2011a;176(2–3):145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng J, Yang R, Whiffin V, Cox P, Ryan U. Identification of zoonotic Cryptosporidium and Giardia genotypes infecting animals in Sydney's water catchments. Exp Parasitol. 2011b;128(2):138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abeywardena H, Jex AR, Firestone SM, McPhee S, Driessen N, Koehler AV, et al. Assessing calves as carriers of Cryptosporidium and Giardia with zoonotic potential on dairy and beef farms within a water catchment area by mutation scanning. Electrophoresis. 2013a;34(15):2259–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abeywardena H, Jex AR, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Haydon SR, Stevens MA, Gasser RB. First molecular characterisation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from Bubalus bubalis (water buffalo) in Victoria, Australia. Infect Genet Evol. 2013b; 20:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang R, Fenwick S, Potter A, Ng J, Ryan U. Identification of novel Cryptosporidium genotypes in kangaroos from Western Australia. Vet Parasitol. 2011;179(1–3):22–27. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nolan MJ, Jex AR, Koehler AV, Haydon SR, Stevens MA, Gasser RB. Molecular-based investigation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from animals in water catchments in southeastern Australia. Water Res. 2013;47(5):1726–1740. 10.1016/j.watres.2012.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koehler AV, Whipp MJ, Haydon SR, Gasser RB. Cryptosporidium cuniculus—new records in human and kangaroo in Australia. Parasit Vectors. 2014a;7:492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang R, Jacobson C, Gardner G, Carmichael I, Campbell AJ, Ng-Hublin J, et al. Longitudinal prevalence, oocyst shedding and molecular characterisation of Cryptosporidium species in sheep across four states in Australia.Vet Parasitol. 2014a;200(1–2):50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abeywardena H, Jex AR, Gasser RB. A perspective on Cryptosporidium and Giardia, with an emphasis on bovines and recent epidemiological findings. Adv Parasitol. 2015;88:243–301. 10.1016/bs.apar.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson B, Sinclair MI, Forbes AB, Veitch M, Cunliffe D, Willis J, et al. Case-control studies of sporadic cryptosporidiosis in Melbourne and Adelaide, Australia. Epidemiol Infect. 2002;128(3):419–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalmers RM, Ferguson C, Cacciò S, Gasser RB, Abs EL-Osta YG, Heijnen L, et al. Direct comparison of selected methods for genetic categorisation of Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis species. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35(4):397–410. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jex AR, Whipp M, Campbell BE, Caccio SM, Stevens M, Hogg G, et al. A practical and cost-effective mutation scanning based approach for investigating genetic variation in Cryptosporidium. Electrophoresis. 2007;28(21):3875–3883. 10.1002/elps.200700279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng J, Eastwood K, Durrheim D, Massey P, Walker B, Armson A, et al. Evidence supporting zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium in rural New South Wales. Exp Parasitol. 2008;119(1):192–195. 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien E, McInnes L, Ryan U. Cryptosporidium gp60 genotypes from humans and domesticated animals in Australia, North America and Europe. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118(1):118–121. 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jex AR, Pangasa A, Campbell BE, Whipp M, Hogg G, Sinclair MI, et al. Classification of Cryptosporidium species from patients with sporadic cryptosporidiosis by use of sequence-based multilocus analysis following mutation scanning. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(7):2252–2262. 10.1128/JCM.00116-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alagappan A, Tujula NA, Power M, Ferguson CM, Bergquist PL, Ferrari BC. Development of fluorescent in situ hybridization for Cryptosporidium detection reveals zoonotic and anthroponotic transmission of sporadic cryptosporidiosis in Sydney. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;75(3):535–539. 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waldron LS, Ferrari BC, Gillings MR, Power ML. Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism for identification of Cryptosporidium species in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009a;75(1):108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waldron LS, Ferrari BC, Power ML. Glycoprotein 60 diversity in C. hominis and C. parvum causing human cryptosporidiosis in NSW Australia. Exp Parasitol. 2009b;122(2):124–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waldron LS, Cheung-Kwok-Sang C, Power ML. Wildlife-associated Cryptosporidium fayeri in human, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(12):2006–2007. 10.3201/eid1612.100715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Power ML, Holley M, Ryan UM, Worden P, Gillings MR. Identification and differentiation of Cryptosporidium species by capillary electrophoresis single-strand conformation polymorphism. FEMS. Microbiol Lett. 2011;314(1):34–41. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02134.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldron LS, Dimeski B, Beggs PJ, Ferrari BC, Power ML. Molecular epidemiology, spatiotemporal analysis, and ecology of sporadic human cryptosporidiosis in Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011a;77(21):7757–7765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waldron LS, Ferrari BC, Cheung-Kwok-Sang C, Beggs PJ, Stephens N, Power ML. Molecular epidemiology and spatial distribution of a waterborne cryptosporidiosis outbreak in Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011b;77(21):7766–7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng J, Eastwood K, Walker B, Durrheim DN, Massey PD, Porgineaux P, et al. Evidence of Cryptosporidium transmission between cattle and humans in northern New South Wales. Exp Parasitol. 2012;130(4):437–441. 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jex AR, Stanley KK, Lo W, Littman R, Verweij JJ, Campbell BE, et al. Detection of diarrhoeal pathogens in human faeces using an automated, robotic platform. Mol Cell Probes. 2012; 26(1):11–15. 10.1016/j.mcp.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koehler AV, Bradbury RS, Stevens MA, Haydon SR, Jex AR, Gasser RB. Genetic characterization of selected parasites from people with histories of gastrointestinal disorders using a mutation scanning-coupled approach. Electrophoresis. 2013;34(12):1720–1728. 10.1002/elps.201300100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng-Hublin JS, Combs B, Mackenzie B, Ryan U. Human cryptosporidiosis diagnosed in Western Australia: a mixed infection with Cryptosporidium meleagridis, the Cryptosporidium mink genotype, and an unknown Cryptosporidium species. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(7):2463–2465. 10.1128/JCM.00424-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang R, Murphy C, Song Y, Ng-Hublin J, Estcourt A, Hijjawi N, Chalmers R, et al. Specific and quantitative detection and identification of Cryptosporidium hominis and C. parvum in clinical and environmental samples. Exp Parasitol. 2013;135(1):142–147. 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koehler AV, Whipp M, Hogg G, Haydon SR, Stevens MA, Jex AR, et al. First genetic analysis of Cryptosporidium from humans from Tasmania, and identification of a new genotype from a traveller to Bali. Electrophoresis. 2014b;35(18):2600–2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Triggs B. Tracks, scats and other traces: a field guide to Australian mammals. Oxford University Press, South Melbourne: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox P, Griffith M, Angles M, Deere D, Ferguson C. Concentrations of pathogens and indicators in animal feces in the Sydney watershed. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(10):5929–5934. 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5929-5934.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.U.S. Environment Protection Agency. Method 1623: Cryptosporidium and Giardia in water by filtration. IMS/IFA EPA-821-R99-006. Office of Water, U.S. Environment Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. 2012.

- 46.King BJ, Keegan AR, Monis PT, Saint CP. Environmental temperature controls Cryptosporidium oocyst metabolic rate and associated retention of infectivity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(7):3848–3857. 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3848-3857.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang R, Paparini A, Monis P, Ryan U. Comparison of next-generation droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) with quantitative PCR (qPCR) for enumeration of Cryptosporidium oocysts in faecal samples. Int J Parasitol. 2014b;44(14):1105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silva SOS, Richtzenhain LJ, Barros IN, Gomes AM, Silva AV, Kozerski ND, et al. A new set of primers directed to 18S rRNA gene for molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp. and their performance in the detection and differentiation of oocysts shed by synanthropic rodents. Exp Parasitol. 2013;135(3):551–557. 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng MM, Wilson ML, Holland RE, Meshnick SR, Lal AA, Xiao L. Genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. in cattle in Michigan: implications for understanding the transmission dynamics. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:175–180. 10.1007/s00436-003-0834-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou L, Singh A, Jiang J, Xiao L. Molecular surveillance of Cryptosporidium spp. in raw wastewater in Milwaukee: implications for understanding outbreak occurrence and transmission dynamics. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(11):5254–5257. 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5254-5257.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao L, Alderisio K, Limor J, Royer M, Lal AA. Identification of species and sources of Cryptosporidium oocysts in storm waters with a small-subunit rRNA-based diagnostic and genotyping tool. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(12):5492–5498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Webber MA, Sari I, Hoefel D, Monis PT, King BJ. PCR slippage across the ML-2 microsatellite of the Cryptosporidium MIC1 locus enables development of a PCR assay capable of distinguishing the zoonotic Cryptosporidium parvum from other human infectious Cryptosporidium species. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014;61(5):324–337. 10.1111/zph.12074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alves M, Xiao L, Sulaiman I, Lal AA, Matos O, Antunes F. Subgenotype analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans, cattle, and zoo ruminants in Portugal. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2744–2747. 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2744-2747.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hadfield SJ, Robinson G, Elwin K, Chalmers RM. Detection and differentiation of Cryptosporidium spp. in human clinical samples by use of real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:918–924. 10.1128/JCM.01733-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morgan UM, Constantine CC, Forbes DA, Thompson RC. Differentiation between human and animal isolates of Cryptosporidium parvum using rDNA sequencing and direct PCR analysis. J Parasitol. 1997;83(5):825–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhalchandra S, Ludington J, Coppens I, Ward HD. Identification and characterization of Cryptosporidium parvum Clec, a novel C-type lectin domain-containing mucin-like glycoprotein. Infect Immun. 2013;81(9):3356–3365. 10.1128/IAI.00436-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strong WB, Gut J, Nelson RG. Cloning and sequence analysis of a highly polymorphic Cryptosporidium parvum gene encoding a 60-kilodalton glycoprotein and characterization of its 15- and 45-kilodalton zoite surface antigen products. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4117–4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li N, Xiao L., Alderisio K, Elwin K, Cebelinski E, Chalmers R, et al. Subtyping Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, a zoonotic pathogen emerging in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20: 217–224. 10.3201/eid2002.121797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rozsa L, Reiczigel J, Majoros G. Quantifying parasites in samples of hosts. J Parasitol. 2000;86:28–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Power ML, Sangster NC, Slade MB, Veal DA. Patterns of Cryptosporidium oocyst shedding by eastern grey kangaroos inhabiting an Australian watershed. Appl. Environmen Microbiol. 2005;71(10):6159–6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Putignani L, Possenti A, Cherchi S, Pozio E, Crisanti A, Spano F. The thrombospondin-related protein CpMIC1 (CpTSP8) belongs to the repertoire of micronemal proteins of Cryptosporidium parvum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;157:98–101. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cacciò S, Spano F, Pozio E. Large sequence variation at two microsatellite loci among zoonotic (genotype C) isolates of Cryptosporidium parvum. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:1082–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hill NJ, Deane EM, Power ML. Prevalence and genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates from common brushtail possums (Trichosuris vulpecula) adapted to urban settings. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(17):5549–5555. 10.1128/AEM.00809-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dowle M, Hill NJ, Power ML. Cryptosporidium from free ranging marsupial host: Bandicuts in urban Australia. Vet Parasitol. 2013;198(1–2):197–200. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vermeulen ET, Ashworth DL, Eldridge MDB, Power ML. Diversity of Cryptosporidium in brush tailed rock wallabies (Petrogale penicillata) managed within a species recovery programme. Int J Parasitol Parasite Wildl. 2015;4(2):190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chalmers RM, Elwin K, Hadfield SJ, Robinson G. Sporadic human cryptosporidiosis caused by Cryptosporidium cuniculus, United Kingdom, 2007–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(3):536–538. 10.3201/eid1703.100410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elwin K, Hadfield SJ, Robinson G, Chalmers RM. The epidemiology of sporadic human infections with unusual cryptosporidia detected during routine typing in England and Wales, 2000–2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:673–683. 10.1017/S0950268811000860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molloy SF, Smith HV, Kirwan P, Nichols RA, Asaolu SO, Connelly L, et al. Identification of a high diversity of Cryptosporidium species genotypes and subtypes in a pediatric population in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(4):608–613. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.ANOFEL Cryptosporidium National Network. Laboratory-based surveillance for Cryptosporidium in France, 2006–2009. Euro Surveill 2010;15(33):19642 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ng JS, Pingault N, Gibbs R, Koehler A, Ryan U. Molecular characterisation of Cryptosporidium outbreaks in Western and South Australia. Exp Parasitol. 2010;125(4):325–328. 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ng-Hublin JS, Hargrave D, Combs B, Ryan U. Investigation of a swimming pool-associated cryptosporidiosis outbreak in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(5):1037–1041. 10.1017/S095026881400106X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Segura R, Prim N, Montemayor M, Valls ME, Muñoz C. Predominant virulent IbA10G2 Subtype of Cryptosporidium hominis in human isolates in Barcelona: A Five-Year Study. PLoS One. 2015:10(3);e0121753 10.1371/journal.pone.0121753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abeywardena H, Jex AR, Nolan MJ, Haydon SR, Stevens MA, McAnulty RW, et al. Genetic characterisation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from dairy calves: discovery of species/genotypes consistent with those found in humans. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1984–1993. 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith HV, Nichols RA, Mallon M, Macleod A, Tait A, Reilly WJ, et al. Natural Cryptosporidium hominis infections in Scottish cattle. Vet Rec. 2005;156:710–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Feng Y, Ortega Y, He G, Das P, Xu M, Zhang X, et al. Wide geographic distribution of Cryptosporidium bovis and the deer-like genotype in bovines. Vet Parasitol. 2007;144:1–9. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Park JH, Guk SM, Han ET, Shin EH, Kim JL, Chai JY. Genotype analysis of Cryptosporidium spp. prevalent in a rural village in Hwasun-gun, Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2006;44:27–33. 10.3347/kjp.2006.44.1.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sharma P, Sharma A, Sehgal R, Malla N, Khurana S. Genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium isolates from patients in North India. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(8):601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Feng Y, Tiao N, Li N, Hlavsa M, Xiao L. Multilocus sequence typing of an emerging Cryptosporidium hominis subtype in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:524–530. 10.1128/JCM.02973-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guo Y, Tang K, Rowe LA, Li N, Roellig DM, Knipe K, et al. Comparative genomic analysis reveals occurrence of genetic recombination in virulent Cryptosporidium hominis subtypes and telomeric gene duplications in Cryptosporidium parvum. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:320 10.1186/s12864-015-1517-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Robinson G, Elwin K, Chalmers RM. Unusual Cryptosporidium genotypes in human cases of diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1800–1802. 10.3201/eid1411.080239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Operario DJ, Bristol LS, Liotta J, Nydam DV, Houpt ER. Correlation between diarrhea severity and oocyst count via quantitative PCR or fluorescence microscopy in experimental cryptosporidiosis in calves. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(1):45–49. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Davies CM, Kaucner C, Deere D, Ashbolt NJ. Recovery and enumeration of Cryptosporidium parvum from animal fecal matrices. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(5):2842–2827. 10.1128/AEM.69.5.2842-2847.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Swaffer BA, Vial HM, King BJ, Daly R, Frizenschaf J, Monis PT. Investigating source water Cryptosporidium concentration, species and infectivity rates during rainfall-runoff in a multi-use catchment. Water Res. 2014;67:310–320. 10.1016/j.watres.2014.08.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.King BJ, Monis PT. Critical processes affecting Cryptosporidium oocyst survival in the environment. Parasitol. 2007;134:309–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoder JS, Beach MJ. Cryptosporidium surveillance and risk factors in the United States. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124(1):31–39. 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sanger sequencing results for this study and NCBI Genbank accession numbers have been provided: KX375346, KX375347, KX375348, KX375349, KX375350, KX375351, KX375352, KX375353, KX375354, KX375355.