Abstract

Objective:

To examine whether socioeconomic and health-related factors explain ethnic disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations among middle-aged and older Israeli adults.

Method:

We used data from Waves I–III of the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe in Israel. Logistic and multinomial regression models were estimated to examine the association between ethnicity and transitions in functional status (onset versus progression) from respondents’ baseline interview (Wave I or II) to their follow-up interview (Wave II or III).

Results:

Compared to veteran Jews, Arabs and Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union were more likely to experience an onset of functional limitations. Arabs were also more likely to experience worsening functional limitations by follow-up. Education and health-related factors attenuated some of the ethnic disparities in onset and progression of functional limitations.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest the importance of moving beyond traditional indicators of socioeconomic status and health-related pathways to fully understand the underlying factors that predict ethnic disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations in Israel.

Key words: Education, Ethnic disparities, Functional limitations, Income, Israel, Socioeconomic status

Background

Functional status is a key dimension of health and reflects older adults’ ability to live active and independent lives. In Israel, significant ethnic disparities in functional limitations and disability exist. Arab Israelis, who include Palestinians who remained in Israel after 1948 and their descendants, as well as immigrant Jews who arrived in Israel mainly in the early 1990s following the collapse of the former Soviet Union (hereafter FSU immigrants) experience higher rates of functional limitations and disability in older adulthood compared to the majority Jewish population (Azaiza & Brodsky, 2003; Brodsky & Litwin, 2005; Osman & Walsemann, 2013). The majority Jewish population, also commonly referred to as “veteran Jews” because its Hebrew translation “vateek” means “old-timers in the country” (Litwin, 2009), is comprised of Jews who immigrated to Israel prior to 1990 or were born in Israel.

Despite ample evidence of ethnic disparities in functional limitations and disability in the adult Israeli population, we know little about where those disparities are produced along the disablement process (Verbrugge & Jette, 1994). That is, ethnic disparities in functional limitations may occur in the onset of functional limitations or in the progression of functional limitations or both. Further, the factors that predict ethnic disparities in the onset of functional limitations may be different than the factors that result in the improvement or worsening of functional limitations. Our study aims to overcome this limitation by examining the extent to which ethnicity is associated with transitions in functional status among middle-aged and older adults in Israel and the mechanisms that explain these ethnic disparities.

One of the strongest and most consistent predictors of functional limitations is socioeconomic status (SES); higher SES is associated with fewer functional limitations (Berkman & Gurland, 1998; Crimmins & Hagedorn, 2010; Haas, 2008; Mendes de Leon, Barnes, Bienias, Skarupski, & Evans, 2005; Minkler, Fuller-Thomson, & Guralnik, 2006), both in terms of the onset of functional limitations and its progression. For example, Zimmer and House (2003) found that U.S. adults with more education and greater income were less likely to experience an onset of functional limitations. Further, individuals with the highest income were most likely to experience improvement in functional limitations and least likely to experience worsening in functional limitations over time, in comparison to those with the lowest income. Similarly, Herd, Goesling, and House (2007) found that education was more predictive of the onset of functional limitations and of chronic conditions than income, whereas income was associated more strongly with the progression of both.

Thus, education and income, though interrelated, may impact functional status differently. Education, often completed earlier in the adult life course, can represent lifelong exposure to major psychosocial, behavioral, cognitive, and biomedical risk factors, all of which contribute to ill health and functional limitations (Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2008; Elo, 2009). Income, on the other hand, often represents the material and, to some extent, the social resources available for the treatment or management of a disease (Herd et al., 2007; Zimmer & House, 2003). As a result, education may be more strongly related to the onset of functional limitations, whereas income may be more strongly related to its progression.

Besides education and income, an important dimension of SES in older adulthood is wealth. Among retired adults, for example, income and occupation often lose their significance as indicators of SES and wealth becomes a more accurate representation of access to material and social resources (Alessie, Lusardi, & Aldershof, 1997; Buckley, Denton, Robb, & Spencer, 2004; Torrey & Taeuber, 1986; Van Ourti, 2003). For example, a study of middle-aged and older Spaniards found that housing assets, but not income, were significantly and positively associated with better self-rated health and lower odds of disability in older adulthood (Costa-Font, 2008). Thus, like income, wealth may also contribute to the progression of functional limitations.

Significant differences in SES and wealth exist between Arabs, FSU immigrants, and veteran Jews; therefore, SES may be a key mechanism driving ethnic disparities in functional limitations among older Israeli adults. Arabs—the largest ethnic minority in Israel—on average complete fewer years of education, earn lower wages, and hold less wealth compared to veteran Jews (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2008; Hesketh, Bishara, Rosenberg, & Zaher, 2011; Okun & Friedlander, 2005; Semyonov & Lewin-Epstein, 2011). Conversely, FSU immigrants are highly educated; more than two-thirds have at least some college education (Heilbrunn, Kushnirovich, & Zeltzer-Zubida, 2010). Upon immigrating to Israel, however, many FSU immigrants experienced downward occupational mobility (Litwin & Leshem, 2008; Raijman & Semyonov, 1998). This was due, in part, to a significant decline in the amount of government assistance available to FSU immigrants compared to prior waves of immigrants (Doron & Kargar, 1993) coupled with the challenges that Israel faced in attempting to absorb large numbers of FSU immigrants in the face of high rates of unemployment in the early 1990s (Beenstock & Ben Menahem, 1997). Despite improvements in FSU immigrants’ occupational and economic status over time, they continue to lag behind veteran Jews (Semyonov & Lewin-Epstein, 2011).

Other more proximal determinants may also help to explain ethnic disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations among Israeli mid-life and older adults. Smoking, physical inactivity, obesity, and poor cognitive functioning are all associated with an increased risk of disability in older adulthood (McGuire, Ford, & Ajani, 2006; Vita, Terry, Hubert, & Fries, 1998). Moreover, declines in cognitive functioning can impact individuals’ adherence to medical treatments and drug protocols, ability to self-care, and utilization of health care services, all of which, in turn, may influence the onset and progression of functional limitations.

Arabs and FSU immigrants may be more likely to engage in a number of these risky health behaviors. For example, Arab men are more likely to smoke (43.8%) compared to Jewish men (23.7%), Jewish women (15.9%), and Arab women (6.7%) (Ministry of Health, 2015). Arabs are also less likely to be physically active and more likely to be obese than Jews (Ministry of Health, 2010). Other studies have documented higher smoking rates for FSU immigrant men compared to veteran Jewish men (Baron-Epel, Haviv-Messika, Tamir, Nitzan-Kaluski, & Green, 2004), but less is known about their engagement with other health behaviors. Additionally, we know of no data that provide estimates on ethnic differences in cognitive functioning among older Israeli adults, but given that higher education is associated with a slower decline in cognitive functioning (Alley, Suthers, & Crimmins, 2007), we speculate that cognitive functioning will be poorer among Arabs and higher among FSU immigrants than veteran Jews due to known ethnic disparities in educational attainment.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

We explore ethnic disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations between veteran Jews, FSU immigrants, and Arab Israelis as well as the extent to which socioeconomic indicators (i.e., education, income, and wealth), health behaviors (i.e., smoking and physical activity), body weight, and cognitive function explain the disparities. We hypothesize that, compared to veteran Jews, Arabs and FSU immigrants will be more likely to experience an onset of functional limitations and worsening of functional limitations over time. Of the socioeconomic indicators, we hypothesize that education, more so than income or wealth, will mediate the relationship between ethnicity and onset of functional limitations, whereas income and wealth, more so than education, will mediate the relationship between ethnicity and progression of functional limitations. We also hypothesize that health behaviors, body weight, and cognitive function will help to explain ethnic disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations beyond socioeconomic indicators.

Method

Data

We use prospective data from the Israeli component of the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE-Israel), a nationally representative sample of Israelis aged 50 or older (Litwin & Sapir, 2008). The study used a multistage probability sampling design in which households were sampled from 150 statistical areas. Noninstitutionalized adults aged 50 and older residing in selected households were interviewed in person in Hebrew, Arabic, or Russian. Interviews were conducted on three occasions: 2005–2006 (Wave I), 2009–2010 (Wave II), and 2013 (Wave III). The initial sample consisted of 2,452 age-eligible respondents. A small replenishment sample (n = 401 age-eligible respondents) was added at Wave II.

Sample

Our analytic sample includes all age-eligible respondents who entered the survey at Wave I and were re-interviewed at Wave II (n = 1,906) as well as all age-eligible respondents who entered the survey at Wave II and were re-interviewed at Wave III (n = 294). Based on these criteria, a total of 2,200 respondents were eligible for inclusion in our sample. We excluded 41 respondents who reported no functional limitations at their baseline interview but died by follow-up because the number of Arabs and FSU immigrants who died was too small to provide stable estimates. Our final analytic sample includes 2,159 respondents (1,466 Israeli Jews, 292 Arabs, and 401 FSU immigrants).

A total of 653 respondents were lost to follow-up. Supplemental analysis indicated that loss to follow-up was more common among younger respondents, men, FSU immigrants, and those with lower education and less common among Arabs and those who were physically active.

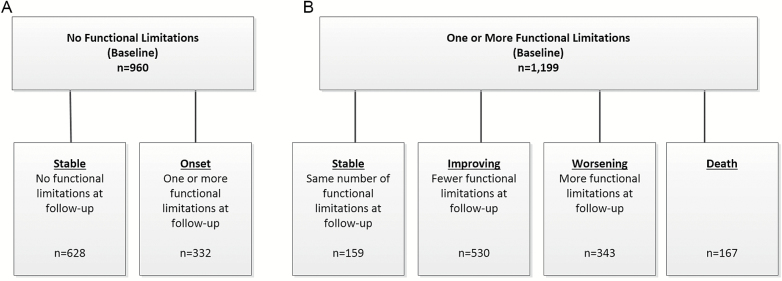

We model two sets of transitions in functional limitations between the baseline interview (Wave I or Wave II) and the follow-up interview (Wave II or Wave III): onset and progression of functional limitations (see Figure 1). Our onset sample includes 960 respondents who reported no functional limitations at their baseline interview. Our progression sample includes 1,199 respondents who reported at least one functional limitation at their baseline interview.

Figure 1.

Transitions modeled in the (A) Onset model and (B) Progression model.

Measures

Dependent variables

Transitions in functional limitations

Our measure of functional limitations assesses restrictions in basic physical functions and fine motor skills (Guralnik & Ferrucci, 2003). At each wave, respondents were asked if they had any difficulty (yes/no): (1) walking 100 m; (2) sitting for about 2hr; (3) getting up from a chair after sitting for long periods; (4) climbing several flights of stairs without resting; (5) climbing one flight of stairs without resting; (6) stooping, kneeling, or crouching; (7) reaching or extending your arms above shoulder level; (8) pulling or pushing large objects like a living room chair; (9) lifting or carrying weights over 10 lb/5 kg, like a heavy bag of groceries; and (10) picking up a small coin from a table. The items were summed into a count of functional limitations (range 0–10).

To model onset of functional limitations (see Figure 1A), respondents were categorized as moving from a state of no functional limitations at their baseline interview to (a) no functional limitations at follow-up (i.e., stable) or (b) at least one functional limitation at follow-up (i.e., onset).

To model progression in functional limitations (see Figure 1B), respondents were categorized as moving from a state of having at least one functional limitation at their baseline interview, to (a) fewer functional limitations at follow-up (i.e., improvement); (b) no change in the number of functional limitations at follow-up (i.e., stable); (c) more functional imitations at follow-up (i.e., worsening); and (d) death by follow-up. These transition categories were based on prior research (Herd et al., 2007; Zimmer & House, 2003).

Independent Variable

Ethnicity

Using information on language of questionnaire (Hebrew, Arabic, or Russian) and parents’ birthplace, SHARE-Israel researchers categorized respondents as veteran Jews, Arabs, or FSU immigrants.

Mediating Variables

All mediating and control variables were assessed at the respondents’ baseline interview.

Education

Respondents’ highest educational degree attained ranged from no schooling to graduate level education (range 0–5) and was modeled as a continuous variable.

Income

Total household income reflects the annual sum of monthly income from salary, rent, and other sources of all household members. Total household income was reported in Euros and was modeled as a continuous variable. The variable followed a normal distribution, with slight skewness. Transformations did not change the results; thus, we kept income in its original form and top-coded it at the 95th percentile.

Wealth

Household net worth was measured in Euros and calculated by the SHARE-Israel research team as the amount of debt subtracted from assets (e.g., value of real estate, value of businesses, cars, bank accounts, bonds, stocks, mutual funds, retirement accounts, savings for housing, and life insurance). Household net worth followed a normal distribution with a slight tail; thus, we top-coded the variable at the 95th percentile.

To make interpretation of the regression coefficients for household income and net worth more meaningful in our multivariable analyses, we divided by 1,000. Thus, a one unit change in income or wealth represents a change of €1,000.

Chronic diseases

Number of physician diagnosed chronic health conditions were reported by respondents. These included having a heart attack, hypertension, a stroke, diabetes, chronic lung disease, cancer, Parkinson disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, arthritis, or any other disease or condition (range 0–10).

Health behaviors

Health behaviors include smoking and physical activity. To assess smoking behavior, respondents were categorized as (a) current smokers if they had ever smoked daily for a period of at least 1 year and smoked at the time of the survey; (b) former smokers if they had ever smoked daily for a period of at least 1 year but did not smoke at the time of the survey; and (c) nonsmokers if they had never smoked daily for a period of at least 1 year and did not smoke at the time of the survey. To assess physical activity, respondents were categorized as “active or somewhat active” if they reported engaging in vigorous physical activity (e.g., sports, heavy housework, or job that involves physical labor) more than once a week; all else were categorized as “inactive.”

Body mass index

Using self-reports of height and weight, respondents were categorized as obese (≥30 body mass index [BMI]) and nonobese (<30 BMI). Other specifications of BMI yielded similar results.

Cognitive function

Two measures assess cognitive functioning. The first, orientation to time, included four items that required the respondent to name the date, month, year, and day of the week. One point was scored for each correct answer. The items were summed (range 0–4) such that higher values indicate better orientation to time. The second, memory function, was assessed using an immediate and delayed free-recall test. Ten short, concrete, high-frequency nouns were read to the respondent, who was then asked to recall as many of them as possible. After about 5min had passed, the respondent was asked to recall the 10 nouns previously presented. The number of correctly recalled nouns, of a maximum of 10, was scored for both immediate and delayed recall performance. Following previous research (Herzog & Wallace, 1997), the number of correctly recalled nouns on the immediate and delayed free-recall tests was summed to create a total score of memory function (range 0–20). Higher scores reflect better memory function. Both measures have shown good construct validity in previous studies.

Covariates

To account for the possibility that baseline functional status rather than ethnicity, education, income, or other aforementioned mediators predict progression of functional limitations, we adjust for the number of functional limitations (range 0–10) respondents reported at their baseline interview. All models also include age (in years), gender, marital status (married versus unmarried), and the wave the respondent entered the study (Wave I or II).

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the association between ethnicity and onset of functional limitations using logistic regression and estimated the association between ethnicity and progression of functional limitations using multinomial logistic regression. For each set of transitions (onset and progression), we estimated two adjusted nested models. In Model 1, we examined the association between ethnicity and transitions in functional limitations while adjusting for demographics and baseline interview. In Model 2, we further adjusted for education, income, wealth, number of chronic diseases, health behaviors, BMI, and cognitive function to examine whether these factors mediate the relationship between ethnicity and transitions in functional limitations. We imputed data using the mi impute command with chained equations specification in Stata v13. This process produced five data sets. All analyses were replicated across the five datasets and combined using mi estimate in Stata v13. We interpret odds ratios (ORs) from logistic regression models and relative risk ratios (RRRs) from multinomial regression models. All analyses were weighted using baseline sampling weights to account for unequal sampling probabilities using the svy command in Stata.

We use the khb command in Stata (Karlson, Holm, & Breen, 2012) to examine the relative contribution of each mediator in explaining the association between ethnicity and functional limitations (onset vs. progression). The KHB method compares the estimated coefficients of nested nonlinear probability models, and hence, decomposes the total effect of the independent variable (i.e., ethnicity) into direct and indirect effects. We report the total percentage of the effect of ethnicity that is explained by all mediators jointly and the percentage of the effect of ethnicity that is explained uniquely by each mediator in Table 3.

Table 3.

Decomposition of the Ethnicity Coefficient Using the Karlson, Holm, and Breen (KHB) Method

| Onset model (n = 960), % | Progression model (n = 1,199), % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabs | FSU immigrants | Arabs | FSU immigrants | |||||

| Improving | Worsening | Death | Improving | Worsening | Death | |||

| Total % of the ethnicity coefficient explained by all mediators | 25.4* | −1.8 | 32.6 | 15.4 | 50.8 | −2.8 | 181.0* | −58.7† |

| % of the ethnicity coefficient uniquely explained by each mediator | ||||||||

| Education | 18.0* | −13.6* | 12.8 | 22.5* | 116.1† | −12.4 | 135.6* | −36.1† |

| Household income (€) | 1.9 | 1.4 | −15.9 | 1.6 | −16.9 | −7.1 | −3.6 | −2.6 |

| Household net worth (€) | 8.6 | 11.5 | 0.2 | −5.3 | −27.4 | 0.8 | 36.1 | −8.6 |

| # of chronic diseases | −2.8 | −3.8 | 25.4† | 0.8 | 43.3† | 5.8 | −1.2 | 3.1 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Never smokera | ||||||||

| Current smoker | 0.0 | 0.17 | 5.6 | 0.8 | −14.8 | 9.2 | −7.9 | −7.8 |

| Former smoker | −1.1 | −0.8 | 6.7 | −0.4 | −18.5 | 3.2 | 1.0 | −2.7 |

| Physical activity | ||||||||

| Inactivea | ||||||||

| Somewhat active | −0.9 | 2.1 | −1.7 | −8.6† | −46.3 | 0.6 | −18.7 | 5.1 |

| BMI | ||||||||

| Nonobesea | ||||||||

| Obese | 1.4 | −1.6 | 0.1 | −0.5 | −3.1 | 0.2 | 6.4 | −2.0 |

| Orientation to time score | 0.8 | 3.3 | 0.2 | 4.6 | 19.2 | −0.2 | 29.9 | −6.3 |

| Memory function score | −0.5 | −0.3 | −0.7 | −0.1 | −0.5 | −2.9 | 3.5 | −0.6 |

Notes. Positive values indicate attenuation of the association between ethnicity and functional limitations. Negative values indicate suppression of the association between ethnicity and functional limitations. BMI = body mass index; FSU = former Soviet Union.

aReference group.

*p < .05. † p < .10 (two-tailed test).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics for the onset and progression samples. In the onset sample, the mean age was 62 (range 51–94). Most respondents were veteran Jews (80%), 8% were Arabs, and 12% were FSU immigrants. Forty-seven percent were women and over 80% were married. The average household income was €36,000, about a fifth of respondents were current smokers, and over 40% were physically inactive. Almost two-thirds of respondents experienced an onset of functional limitations by follow-up (64%).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics of Israeli Adults Aged 50 and Older, SHARE-Israel, Waves I, II, and III, Weighted Estimates

| Onset sample (n = 960) | Progression sample (n = 1,199) | |

|---|---|---|

| % or mean (SE) | % or mean (SE) | |

| Onset transitions | ||

| No onset | 64% | |

| Onset | 36% | |

| Progression transitionsa | ||

| Stable | 12% | |

| Improving | 46% | |

| Worsening | 26% | |

| Death | 16% | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Veteran Jews | 80% | 59% |

| Arab Israelis | 8% | 11% |

| FSU immigrants | 12% | 30% |

| Age (years) | 62 (0.3) | 69 (0.4) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 47% | 62% |

| Male | 53% | 38% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 83% | 66% |

| Not married | 17% | 34% |

| Baseline interview | ||

| Wave 1 | 95% | 87% |

| Wave 2 | 5% | 13% |

| Education | 3.4 (0.05) | 2.9 (0.06) |

| Household income (€) | 36,400 (1271.2) | 27,800 (896.5) |

| Household net worth (€) | 231,900 (12344.6) | 143,800 (7124.0) |

| # of chronic diseases (0 – 10) | 1.1 (0.04) | 2.6 (0.06) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never smoker | 52% | 64% |

| Current smoker | 21% | 12% |

| Former smoker | 27% | 24% |

| Physical activity | ||

| Inactive | 42% | 75% |

| Somewhat active | 58% | 25% |

| BMI | ||

| Nonobese | 83% | 76% |

| Obese | 17% | 24% |

Notes. BMI = body mass index; FSU = former Soviet Union.

aProgression transitions: Stable = having same number of functional limitations at follow-up as baseline; Improving = having fewer functional limitations at follow-up than at baseline; Worsening = having more functional limitations at follow-up than at baseline.

The progression sample was on average older (M = 69; range 51–95), included fewer veteran Jews (60%), more women (62%), and lower annual income (€27,800) than the onset sample. Fully three-quarters were physically inactive. The most common transition in functional limitations was one of improvement—46% reported fewer functional limitations at follow-up than at baseline, although 26% reported more functional limitations at follow-up and 16% had died.

Logistic Regression Analyses – Onset of Functional Limitations

Table 2 presents results from the onset model. Adjusting for demographics and baseline interview (Model 1), the odds of experiencing an onset of functional limitations were six times greater for Arabs (OR = 6.6; 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.7, 11.6) and FSU immigrants (OR = 6.4; 95% CI: 2.4, 17.6) than for veteran Jews. The odds of experiencing an onset of functional limitations were significantly attenuated for Arabs (OR = 4.6; 95% CI: 2.4, 8.7), but not for FSU immigrants (OR = 7.5; 95% CI: 2.5, 22.0), once the mediators were included (Model 2).

Table 2.

ORs (95% CIs) From Logistic Regression Models Predicting Onset of Functional Limitations Among Israelis Aged 50 and Older, n = 960, Weighted Estimates

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Veteran Jewsa | ||

| Arab Israelis | 6.6* (3.7, 11.6) | 4.6* (2.4, 8.7) |

| FSU immigrants | 6.4* (2.4, 17.6) | 7.5* (2.5, 22.0) |

| Education | 0.8* (0.7, 0.9) | |

| Household income (€) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | |

| Household net worth (€) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | |

| # of chronic diseases | 1.2† (1.0, 1.4) | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never smokera | ||

| Current smoker | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | |

| Former smoker | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | |

| Physical activity | ||

| Inactivea | ||

| Somewhat active | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | |

| BMI | ||

| Nonobesea | ||

| Obese | 1.4 (0.9, 2.2) | |

| Orientation to time score | 0.5* (0.3, 0.8) | |

| Memory function score | 1.0 (0.9, 1.0) | |

Notes. All covariates measured at the baseline interview. Income and net worth divided by 1,000. Models 1 and 2 adjust for age, sex, marital status, and wave of baseline survey participation. BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; FSU = former Soviet Union; OR = odds ratio.

aReference group.

*p < .05. † p < .10 (two-tailed test).

Decomposition of Effects – Onset Model

Table 3 presents results from the decomposition of effects for the onset model. Among Arabs, the inclusion of the set of mediators accounted for 25.4% of the association between ethnicity and onset of functional limitations (p < .05). Education uniquely accounted for 18% of this association (p < .05); however, no other mediators uniquely explained the association.

Among FSU immigrants, the inclusion of the set of mediators did not account for a significant percentage of the association between ethnicity and onset of functional limitations. Education, though, appeared to suppress about 14% of the association between ethnicity and onset (p < .05). No other mediators uniquely explained the association among FSU immigrants.

Multinomial Regression Analyses – Progression of Functional Limitations

Table 4 displays results from the progression model. Those who reported the same number of functional limitations at follow-up serve as the reference category. After adjustment for demographics, baseline interview, and the number of functional limitations reported at the baseline interview (Model 1), Arabs and FSU immigrants did not differ from veteran Jews in their relative risk of experiencing improvement in functional limitations by follow-up. For Arabs as compared to veteran Jews, however, the relative risk of experiencing worsening functional limitations relative to remaining stable increased by a factor of 3.4 (95% CI: 1.7, 6.8). For FSU immigrants as compared to veteran Jews, the relative risk of dying by follow-up relative to remaining stable increased by a factor of 2.8 (95% CI: 1.1, 7.5).

Table 4.

RRRs (95% CI) From Multinomial Regression Models Predicting Progression of Functional Limitations Among Israelis Aged 50 and Older, n = 1,199, Weighted Estimates

| Improving | Worsening | Death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Veteran Jewsa | ||||||

| Arabs | 1.4 (0.7, 2.6) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.6) | 3.4* (1.7, 6.8) | 3.0* (1.4, 6.7) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.2) | 1.1 (0.4, 3.0) |

| FSU immigrants | 1.6 (0.8, 3.4) | 1.6 (0.7, 3.8) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.7) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.5) | 2.8* (1.1, 7.5) | 5.3* (1.6, 17.1) |

| Education | 0.9 (0.8, 1.2) | 0.8* (0.6, 1.0) | 0.8† (0.6, 1.0) | |||

| Household income (€) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | |||

| Household net worth (€) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | |||

| # of chronic diseases | 0.9*(0.7, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.1) | 0.8* (0.7, 1.0) | |||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smokera | ||||||

| Current smoker | 0.7 (0.3, 1.3) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | 2.2† (0.9, 5.1) | |||

| Former smoker | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.7, 2.3) | |||

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Inactivea | ||||||

| Somewhat active | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | 0.6† (0.3, 1.0) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.5) | |||

| BMI | ||||||

| Nonobesea | ||||||

| Obese | 1.0 (0.6, 2.6) | 1.6† (0.9, 2.7) | 1.6 (0.7, 3.7) | |||

| Orientation to time score | 1.0 (0.7, 1.3) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | |||

| Memory function score | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | |||

Notes. Stable = having same number of functional limitations at follow-up as baseline and is the comparison group; Improving = having fewer functional limitations at follow-up than at baseline; Worsening = having more functional limitations at follow-up than at baseline. Household income and net worth divided by 1,000. Models 1 and 2 adjust for age, gender, marital status, baseline wave of survey participation, and number of functional limitations, all measured at the baseline interview. BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; FSU = former Soviet Union; RRR = relative risk ratio.

aReference group.

*p < .05. † p < .10 (two-tailed test).

After the inclusion of mediators (Model 2), the higher relative risk of experiencing worsening functional limitations by follow-up among Arabs as compared to veteran Jews was attenuated but not eliminated (RRR = 3.0; 95% CI: 1.4, 6.7). Conversely, the relative risk of death experienced by FSU immigrants as compared to veteran Jews was greater than found in Model 1 once the mediators were included (RRR = 5.3; 95% CI: 1.6, 17.1).

Decomposition of Effects – Progression Model

Among Arabs, the set of mediators did not explain a significant percentage of the relationship between ethnicity and worsening of functional limitations, the only significant ethnic difference found for the progression model (Table 3). Education, however, uniquely accounted for 22.5% of the effect (p < .05), whereas being somewhat physically active suppressed this effect by about 9% (p < .10).

For FSU immigrants, the set of mediators suppressed about 58% of the relationship between ethnicity and transitioning to death (p < .10). Further, education uniquely suppressed 36% of this effect (p < .10).

Discussion

We examined ethnic disparities in onset versus progression of functional limitations and the possible mechanisms involved in those disparities among a nationally representative sample of mid-life and older Israeli adults. We hypothesized that (a) compared to veteran Jews, Arabs and FSU immigrants would be more likely to experience an onset of functional limitations and a worsening of functional limitations over time; (b) education, more so than income or wealth, would mediate the relationship between ethnicity and onset of functional limitations; (c) income and wealth, more so than education, would mediate the relationship between ethnicity and progression of functional limitations; and (d) health behaviors, body weight, and cognitive function would further explain ethnic disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations beyond education, income, and wealth.

As hypothesized, Arabs and FSU immigrants were more likely to experience an onset of functional limitations compared to veteran Jews. Arabs were also more likely to experience worsening functional limitations by follow-up compared to veteran Jews. These results are consistent with previous studies that show that Arabs and FSU immigrants have poorer physical and mental health outcomes and are more disabled than veteran Jews (Amit & Litwin, 2010; Azaiza & Brodsky, 2003; Baron-Epel & Kaplan, 2009; Brodsky & Litwin, 2005; Ministry of Health, 2010; Osman & Walsemann, 2013).

Whether the consequences of SES on functional limitations in older adulthood are uniform across different national contexts is not clear. U.S. studies provide evidence that education and income are associated with functional limitations in older adulthood and that they often explain part (or most) of the higher risk of functional limitations experienced by racial/ethnic minorities (Haas, 2008; Herd et al., 2007; Minkler et al., 2006). In our study, education was associated with greater odds of onset and worsening of functional limitations by follow-up. Income and wealth, however, did not predict onset or progression of functional limitations. Although education, in part, attenuated the association described above for Arabs, it worked as a suppressor for FSU immigrants. This is not surprising given that FSU immigrants are highly educated but economically disadvantaged compared to veteran Jews due to postmigration downward occupational mobility (Litwin & Leshem, 2008). This suggests that FSU immigrants have been unable to successfully translate their human capital into good health, a finding that has also been documented among U.S. immigrants (Walsemann, Gee, & Ro, 2013).

The null findings for income and wealth suggest that these factors might not work the same way for countries that have different health care and income support policies than those available in the United States. In the United States, income likely influences the resources available to citizens for the treatment and management of chronic diseases and disability. In Israel, citizens have had universal health coverage since 1995, which ensures access to a standardized “basket” of health services, including, but not limited to, medical diagnosis and treatment of chronic diseases, medications, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and more (National Insurance Institute of Israel, 1995). Thus, affordable access to health care services available to all Israeli citizens may reduce the importance of income and wealth for the onset and progression of functional limitations because it can be used to prevent or treat those conditions that might exacerbate or accelerate declines in functional limitations.

Contrary to expectations, health behaviors, body weight, and cognitive function did not explain any of the ethnic disparities in onset and progression of functional limitations. There are a number of possible reasons for these variables’ lack of explanatory power. First, their explanatory power may be captured by the distal determinants of education, income, and wealth. Second, poor measurement of smoking and physical activity may have hindered our ability to detect their mediating effects. For example, vigorous physical activity was assessed by the frequency with which respondents engaged in sports, heavy housework, or jobs that involved physical labor. Such a measurement approach may not have captured individuals who were truly physically active from those who were not.

Our findings point to the possibility that factors beyond SES and health-related pathways may be driving ethnic disparities in onset and progression of functional limitations. Arabs, as the only indigenous, non-Jewish ethnic group in Israel, have collectively endured traumatic experiences and many in our sample are likely to have directly experienced them. These include internal displacement, loss of home and land, and public policies that result in vast inequities in education, neighborhood resources, and occupational mobility (Hesketh et al., 2011; Okun & Friedlander, 2005; Semyonov & Lewin-Epstein, 2011). Collective trauma has been associated with engagement in riskier behaviors and poorer health among American Indians in the United States (Walters et al., 2011). Similarly, Daoud, Shankardass, O’Campo, Anderson, and Agbaria (2012) found that Arabs who were internally displaced after the Nakba of 1948 reported poorer self-rated health than those who were not internally displaced.

FSU immigrants, on the other hand, have had their own unique experiences within the Israeli context. Some have noted FSU immigrants’ lack of full integration into Israeli society postmigration (Al-Haj, 2002; Remennick, 2003). Social integration is central to the development of social networks that can provide access to employment as well as economic and social resources useful for buffering the effects of psychosocial stressors (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000). Lack of social integration may have contributed to FSU immigrants’ postmigration downward mobility and may provide one explanation for why they were at greater risk for onset of functional limitations.

Limitations

First, we examined onset and progression of functional limitations over a 4-year time period. Given this relatively short time span, our results may have underestimated onset and progression of functional limitations in our sample. Additionally, we were limited to the use of two waves of data; more frequent assessments would have increased our chances of capturing the short-term changes in decline and recovery in physical functioning that often occur after a major health shock or fall (Gill, 2014). Still, our study provides preliminary evidence that ethnic disparities among mid-life and older Israeli adults exist in the onset and progression of functional limitations. Second, approximately 23% of respondents did not provide a second interview. Some of the factors that predicted attrition would appear to make our analytic sample a healthier sample (e.g., being inactive, low education, Arab ethnicity), whereas other factors would suggest that our sample would be less healthy (e.g., FSU immigrants). In any case, the greater loss of FSU immigrants, who are on average more functionally limited, may have downwardly biased our estimates for this group. Additionally, our sample is more educated, on average, than the older Israeli adult population, which could be one reason education did not explain more of the ethnic disparities in our sample. Finally, we focus on ethnic disparities between Arabs and FSU immigrants in comparison to veteran Jews; however, there is considerable ethnic heterogeneity within the veteran Jewish population (e.g., European or American Jews vs. Asian or North African Jews). Such disaggregation of ethnic groups was not possible using our data and hence was not addressed in the present analysis.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest large ethnic disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations between Arab, FSU immigrant, and veteran Jewish middle-aged and older adults in Israel. Indicators commonly predictive of functional limitations in the U.S. literature did little to further our understanding of why these ethnic disparities exist in Israel, although education did explain some of the disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations between Arabs and veteran Jews. Thus, our study demonstrates a need to move beyond traditional indicators of SES and wealth to include those factors that have resulted in the marginalization of Arabs and FSU immigrants within Israeli society. Only then may we be able to develop meaningful policies that could reduce ethnic disparities in the onset and progression of functional limitations found in Israel.

Funding

The project development and data collection in Israel was supported by the National Institutes of Health of the United States (NIH), the National Insurance Institute of Israel, The German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development (GIF), and the Ministry of Science and the Ministry of Senior Citizens. The data were collected by the Israeli Gerontological Data Center at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The authors received no direct support for the analyses presented in this paper. The content presented here is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the organizations mentioned above.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jennifer A. Ailshire for her helpful comments on previous drafts of this article. The research reported in this paper used data from the Survey of Health and Retirement in Europe, Israel. A. Osman was responsible for the development of the hypotheses, writing the manuscript, and running all analyses. K. M. Walsemann was responsible for assisting in the development of the hypotheses and the writing of the manuscript.

References

- Alessie R. Lusardi A., & Aldershof T (1997). Income and wealth over the life cycle: Evidence from panel data. Review of Income Wealth, 43, 1–32. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4991.1997.tb00198.x [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haj M. (2002). Identity patterns among immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Israel: Assimilation vs. ethnic formation. International Migration, 40, 49–70. doi:10.1111/1468–2435.00190 [Google Scholar]

- Alley D. Suthers K., & Crimmins E (2007). Education and cognitive decline in older Americans: Results from the AHEAD sample. Research on Aging, 29, 73–94. doi:10.1177/0164027506294245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit K., & Litwin H (2010). The subjective well-being of immigrants aged 50 and older in Israel. Social Indicators Research, 98, 89–104. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9519-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azaiza F., & Brodsky J (2003). The aging of Israel’s Arab population: Needs, existing responses, and dilemmas in the development of services for a society in transition. Israel Medical Association Journal, 5, 383–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Epel O. Haviv-Messika A. Tamir D. Nitzan-Kaluski D., & Green M (2004). Multiethnic differences in smoking in Israel. The European Journal of Public Health, 14, 384–389. doi:10.1093/eurpub/14.4.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Epel O., & Kaplan G (2009). Can subjective and objective socioeconomic status explain minority health disparities in Israel? Social Science & Medicine (1982), 69, 1460–1467. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenstock M., & Ben Menahem Y (1997). The labour market experience of CIS immigrants to Israel: 1989–1994. International Migration, 35, 187–224. doi:10.1111/1468-2435.00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman C. S., & Gurland B. J (1998). The relationship among income, other socioeconomic indicators, and mobility level in older persons. Journal of Aging and Health, 10, 81–98. doi:10.1177/089826439801000105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F. Glass T. Brissette I., & Seeman T. E (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 843–857. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky J., & Litwin H (2005). Immigration, ethnicity and patterns of care among older persons in Israel. Retraite et Société, 44, 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley N. J. Denton F. T. Robb A. L., & Spencer B. G (2004). Healthy aging at older ages: Are income and education important? Canadian Journal on Aging, 23, S155–S169. doi:10.1353/cja.2005.0030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. (2008). The Arab population in Israel. Retrieved from http://www1.cbs.gov.il/www/statistical/arab_pop08e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Font J. (2008). Housing assets and the socio-economic determinants of health and disability in old age. Health & Place, 14, 478–491. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E. M., & Hagedorn A (2010). The socioeconomic gradient in healthy life expectancy. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 30, 305–321. doi:10.1891/0198-8794.30.305 [Google Scholar]

- Cutler D. M., & Lleras-Muney A (2008). Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence. In Schoeni R. F. House J. S. Kaplan G. A., & Pollack H. (Eds.), Making Americans healthier: Social and economic policy as health policy (pp. 29–60). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Daoud N. Shankardass K. O’Campo P. Anderson K., & Agbaria A. K (2012). Internal displacement and health among the Palestinian minority in Israel. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74, 1163–1171. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doron A., & Kargar H (1993). The politics of immigration policy in Israel. International Migration, 31, 497–512. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.1993.tb00681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo I. T. (2009). Social class differentials in health and mortality: Patterns and explanations in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 553–572. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115929 [Google Scholar]

- Gill T. M. (2014). Disentangling the disabling process: Insights from the precipitating events project. The Gerontologist, 54, 533–549. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik J. M., & Ferrucci L (2003). Assessing the building blocks of function: Utilizing measures of functional limitation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 112–121. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00174-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas S. (2008). Trajectories of functional health: The ‘long arm’ of childhood health and socioeconomic factors. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 66, 849–861. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn S. Kushnirovich N., & Zeltzer-Zubida A (2010). Barriers to immigrants’ integration into the labor market: Modes and coping. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34, 244–252. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.02.008 [Google Scholar]

- Herd P. Goesling B., & House J. S (2007). Socioeconomic position and health: The differential effects of education versus income on the onset versus progression of health problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48, 223–238. doi:10.1177/002214650704800302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog A. R., & Wallace R. B (1997). Measures of cognitive functioning in the AHEAD Study. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 52, 37–48. doi:10.1093/geronb/52B.Special_Issue.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh K. Bishara S. Rosenberg R., & Zaher S (2011). Inequality report: The Palestinian Arab minority in Israel. Retrieved from http://adalah.org/upfiles/2011/Adalah_The_Inequality_Report_March_2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Karlson K. B. Holm A., & Breen R (2012). Comparing regression coefficients between same-sample nested models using Logit and Probit: A new method. Sociological Methodology, 42, 286–313. doi:10.1177/0081175012444861 [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H. (2009). Understanding aging in a Middle Eastern context: The SHARE-Israel survey of persons aged 50 and older. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 24, 49–62. doi:10.1007/s10823-008-9073-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H., & Leshem E (2008). Late-life migration, work status and survival: The case of older immigrants from the Former Soviet Union in Israel. International Migration Review, 42, 903–925. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00152.x [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H., & Sapir E. V (2008). The SHARE-Israel methodology (Hebrew). Social Security, 76, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire L. C. Ford E. S., & Ajani U. A (2006). Cognitive functioning as a predictor of functional disability in later life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 36–42. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000192502.10692.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes de Leon C. F. Barnes L. L. Bienias J. L. Skarupski K. A., & Evans D. A (2005). Racial disparities in disability: Recent evidence from self-reported and performance-based disability measures in a population-based study of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, S263–S271. doi:10.1093/geronb/60.5.S263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health (2010). Health status in Israel (Hebrew). Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/Health_Status_in_Israel2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health (2015). The Minister’s report on smoking in Israel (Hebrew). Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/smoking_2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Fuller-Thomson E., & Guralnik J. M (2006). Gradient of disability across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 355, 695–703. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa044316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Insurance Institute of Israel. (1995). The National Health Insurance Law, 1994 (Hebrew). Retrieved from http://www.btl.gov.il/Laws1/00_0003_000000.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Okun B. S., & Friedlander D (2005). Educational stratification among Arabs and Jews in Israel: Historical disadvantage, discrimination, and opportunity. Population Studies, 59, 163–180. doi:10.1080/00324720500099405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A., & Walsemann K. M (2013). Ethnic disparities in disability among middle-aged and older Israeli adults: The role of socioeconomic disadvantage and traumatic life events. Journal of Aging and Health, 25, 510–531. doi:10.1177/0898264313478653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raijman R., & Semyonov M (1998). Best of times, worst of times, and occupational mobility: The case of Soviet immigrants in Israel. International Migration Review, 36, 291–312. doi:10.1111/1468-2435.00048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remennick L. (2003). What does integration mean? Social insertion of Russian immigrants in Israel. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 4, 23–49. doi:10.1007/s12134-003-1018-y [Google Scholar]

- Semyonov M., & Lewin-Epstein N (2011). Wealth inequality: Ethnic disparities in Israeli society. Social Forces, 89, 935–959. doi:10.1353/sof.2011.0006 [Google Scholar]

- Torrey B. B., & Taeuber C. M (1986). The importance of asset income among the elderly. Review of Income & Wealth, 32, 443–449. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4991.1986.tb00550.x [Google Scholar]

- Van Ourti T. (2003). Socio-economic inequality in ill-health amongst the elderly. Should one use current or permanent income? Journal of Health Economics, 22, 219–241. doi:10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00100-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M., & Jette A. M (1994). The disablement process. Social Science & Medicine, 38, 1–14. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vita A. J. Terry R. B. Hubert H. B., & Fries J. F (1998). Aging, health risks, and cumulative disability. The New England Journal of Medicine, 338, 1035–1041. doi:10.1056/NEJM199804093381506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsemann K. M. Gee G. C., & Ro A (2013). Educational attainment in the context of social inequality: New directions for research on education and health. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 1082–1104. doi:10.1177/0002764213487346 [Google Scholar]

- Walters K. L. Mohammed S. A. Evans-Campbell T. Beltan R. E. Chae D. H., & Duran B (2011). Bodies don’t just tell stories, they tell histories: Embodiment of historical trauma among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8, 179–189. doi:10.1017/S1742058X1100018X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z., & House J. S (2003). Education, income, and functional limitation transitions among American adults: Contrasting onset and progression. International Journal of Epidemiology, 32, 1089–1097. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]