Abstract

Patient: Female, 78

Final Diagnosis: Acute myocardial infarction

Symptoms: Chest discomfort

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Cardiology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) can be caused not only by plaque rupture/erosion, but also by many other mechanisms. Thromboembolism due to atrial fibrillation and coronary thrombosis due to coronary artery ectasia are among the causes. Here we report on a case of recurrent myocardial infarction with coronary artery ectasia.

Case Report:

Our case was a 78-year-old woman with hypertension. Within a one-month interval, she developed AMI twice at the distal portion of her right coronary artery along with coronary artery ectasia. On both events, emergent coronary angiography showed no obvious organic stenosis or trace of plaque rupture at the culprit segment after thrombus aspiration. After the second acute event, we started anticoagulation therapy with warfarin to prevent thrombus formation. In the chronic phase, we confirmed, by using coronary angiography, optimal coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound, that there was no plaque rupture and no obvious thrombus formation along the coronary artery ectasia segment of the distal right coronary artery, which suggested effectiveness of anticoagulant. Furthermore, by Doppler velocimetry we found sluggish blood flow only in the coronary artery ectasia lesion but not in the left atrium which is generally the main site of systemic thromboembolism revealed by transesophageal echocardiography.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that the two AMI events at the same coronary artery ectasia segment were caused by local thrombus formation due to local stagnant blood flow.

Although it has not yet been generally established, anticoagulation therapy may be effective to prevent thrombus formation in patients with coronary artery ectasia regardless of the prevalence of atrial fibrillation.

MeSH Keywords: Anticoagulants, Coronary Thrombosis, Myocardial Infarction

Background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) can be caused not only by plaque rupture/erosion, but also by other mechanisms. Among these other mechanisms, thromboembolism due to atrial fibrillation (AF) caused by thrombus formation in left atrium (LA) is known as the major cause of AMI, while coronary thrombosis due to coronary artery ectasia (CAE), which is one of the phenotypes of coronary atherosclerosis, is also reported to be one of the causes [1,2]. Coronary artery ectasia is noted in 3–8% of patients undergoing coronary angiography (CAG), and it sometimes induces AMI regardless of the presence or absence of coronary stenosis or AF [2–5]. Here we report on a case of recurrent AMI at the same CAE lesion and the potential for long-term effectivity of antithrombotic therapy.

Case Report

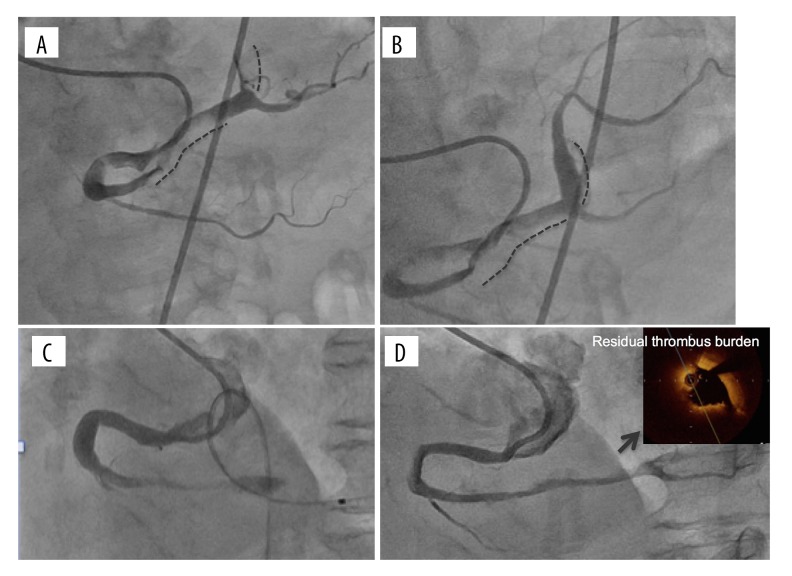

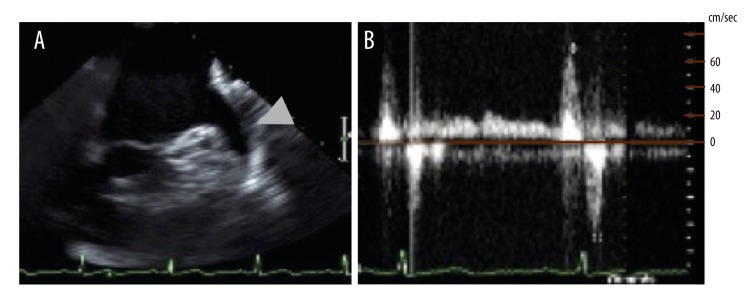

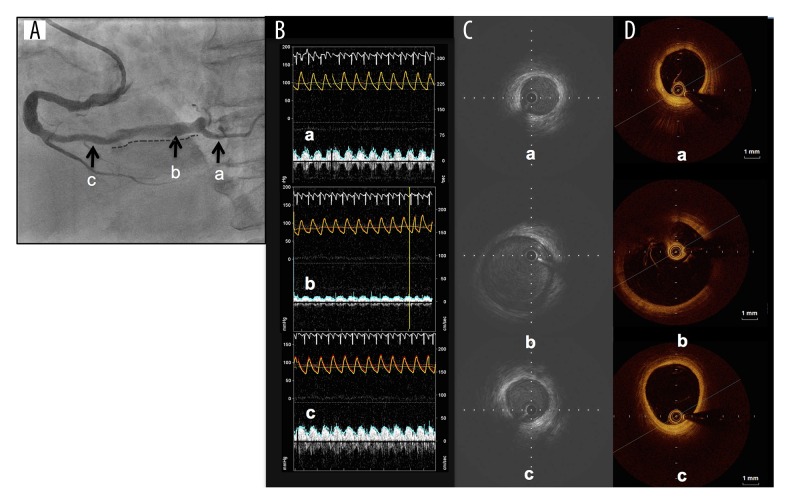

We present a case of a 78-years-old woman who was transferred to our emergency department (ED) because of chest oppression after two hours from symptom onset. Her clinical history was hypertension, and she had previously been administrated antiplatelet agents for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events but the treatment had been stopped several years earlier because of a minor bleeding episode. She did not have any episode of AF, which is a well-known cause of coronary thromboembolism. At the time of her arrival to our ED, her electrocardiography (ECG) showed sinus rhythm and ST elevation in II, III, and aVF, and ST depression in V4–V6. Transthoracic echocardiography showed that her left ventricular (LV) inferior wall motion was severely hypokinetic. From these findings, we promptly diagnosed a case as AMI and immediately performed CAG via the right femoral artery. We found no organic stenosis in the left coronary arteries but found an occlusion at the distal portion of the right coronary artery (RCA) with a filling defect probably due to thrombus (Figure 1A). We then performed coronary intervention using an aspiration device, the Thrombuster III GR catheter (Kaneka Medix Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). After a large amount of red thrombus was aspirated from the atrioventricular node branch (AV branch) and distal RCA, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) grade 3 flow was obtained (Figure 1B). As we did not find obvious organic stenosis on both distal RCA and far distal branches, we did not perform further intervention. An important finding on the final angiography was that the culprit segment i.e., from the distal RCA to the proximal AV branch, had severe ectasia (Figure 1B). The patient’s cardiac function one day after the coronary intervention was preserved; echocardiography showed 52 mm left atrium dimension, 55% LV ejection fraction, although focal akinesis at LV inferior segment was observed. The coagulation function was normal judging from the following laboratory data: protein C activity, protein S activity, lupus anticoagulant, and TPA/plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) complex. Antithrombotic therapy was started immediately via administration of 10,000 units of heparin per day for three days, and the oral antiplatelet agent aspirin, which is recommended for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events [2]. We did not begin administration of anticoagulant at the patient’s initial presentation to our ED because the patient’s cardiac rhythm was sinus rhythm rather than AF and her transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) did not show thrombus in the LV or LA. She was discharged on day 22 after we confirmed the patency of the RCA with CAG, however, she developed AMI at the same culprit lesion on day 24 day from her first discharge (Figure 1C). We subsequently performed a thrombectomy in a similar strategy to the initial treatment but this time we could not obtain a successful recanalization of the AV branch because of the failure of wire crossing. Thus, we crossed the wire to the posterior descending branch (PD branch) and obtained TIMI 3 after aspirating a large amount of red thrombus from the distal RCA. After this intervention, we started the administration of heparin with the same dose at the previous event, and immediately changed the antithrombotic agent from an antiplatelet agent to the anticoagulant warfarin, which had not previously been administrated. On day 22 after the second event, i.e., in sub-acute phase, and under the administration of anticoagulant, we performed CAG, optimal coherence tomography (OCT), and Doppler velocimetry. We confirmed the patency of RCA by CAG, but found residual thrombus along the CAE segment by OCT (Figure 1D). Doppler velocimetry showed an abnormal stagnant flow pattern only within the CAE lesion although the fractional flow reserve (FFR) was 1.0 (data not shown). Finally, before her second discharge, we performed TEE on day 24 of the second event, and found no sign of the typical smoke-like echo or thrombus in her LA or LV, the main common sites of systemic thromboembolism (Figure 2A). The flow velocity in her LA appendage was 69 cm/second (Figure 2B) indicating no stagnant flow. At 12 months after the patient’s initial event, i.e., chronic phase, we performed CAG and confirmed the patency of the distal RCA but occlusion of the AV branch (Figure 3A), and we subsequently performed optimal coherence tomography (OCT) to evaluate the presence or absence of plaque rupture and residual thrombus. We found neither plaque rupture nor obvious thrombus formation along the CAE segment of the distal RCA (Figure 3B). We also performed intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) to evaluate the true vessel shape, and found the CAE segment was 9 mm in diameter and 31 mm in length without obvious rupture-prone atheromatous plaque and thrombus (Figure 3C). Furthermore, we found sluggish blood flow of less than 20 cm/second only in the CAE lesion, but not in the proximal and distal portion of the CAE by Doppler velocimetry study (Figure 3D). From the findings on the latest CAG, OCT, and IVUS, we confirmed that the thrombus on the ectasia lesion had been diminished but sluggish blood flow still remained along the CAE lesion. From these findings, we concluded that we should continue the administration of anticoagulant to prevent thrombosis. Two months after the second event, we changed therapy with warfarin to therapy with the novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) apixaban to improve drug compliance, and we confirmed that coronary events had not occurred since starting the anticoagulant within the past one year.

Figure 1.

Time course of CAG image: (A) before thrombus aspiration at the initial event, dotted line indicates the segment of thrombosis; (B) after thrombus aspiration at the initial event, dotted line indicates the ectasic segment; (C) before thrombus aspiration at the second event; (D) 22 days after the second event with administration of anticoagulant agent (OCT finding at the CAE segment with thrombus super-imposed, in which intima was not observable due to residual thrombus burden), CAG image 12 month after the initial shown in Figure 3A. CAE – coronary artery ectasia; CAG – coronary angiography; OCT – optimal coherence tomography

Figure 2.

TEE findings on day 24 of the second event: (A) LA and appendage, arrowhead indicates the LA appendage; and (B) Doppler velocimetry finding on appendage, the maximum velocity being up to 60 cm/second. LA – left atrium; TEE – transesophageal echocardiography.

Figure 3.

(A) CAG image dotted line indicates the ectasic segment, portions ‘a’ to ‘c’ correspond to distal from CAE, CAE segment, and proximal from CAE respectively; (B) descriptions of CAE vessel anatomy using OCT; (C) description of CAE using IVUS; (D) the coronary flow patterns using Doppler velocimetry in each segment, all 12 month after the initial event with administration of anticoagulant agent. CAE – coronary artery ectasia; CAG – coronary angiography; IVUS – intravascular ultrasound; OCT – optimal coherence tomography.

Discussion

There are few reports in the literature about patients with AMI coexisting with CAE, and the standard therapy for this condition has not been clearly established. Our patient developed two events of AMI at the same CAE segment, which may have been caused by local thrombus formation due to stagnant local blood flow and not plaque rupture or thromboembolism originated from L or LV. In general, thrombus formation in the coronary artery is due to several reasons, including abnormal coagulation system [6,7], coronary plaque rupture on atheromatous plaque and endothelial dysfunction coincident with the lesion [8], and abnormal coronary blood flow, i.e., sluggish flow [5,7,9]. First, we found no abnormality in blood coagulation function in laboratory tests. Second, we did not find any obvious trace of plaque rupture in the culprit lesion with CAE by CAG and OCT performed at the sub-acute phase of the second event under the administration of anticoagulant, and by CAG, OCT and IVUS performed at the chronic phase. Thus, we suspected that plaque rupture due to abnormal intimal function, if any, was not responsible to the recurrent coronary thrombosis. Third, regarding the coronary blood flow abnormality, TEE and Doppler velocimetry performed at the sub-acute phase of the second event under the administration of anticoagulant, found no abnormal stagnant in LA appendage or LV, and abnormal stagnant blood flow only within the CAE, respectively. Optimal coherence tomography performed at the sub-acute phase of the second event showed residual thrombus along CAE segment. Thus, at the sub-acute phase, we diagnosed the CAE to be responsible for coronary thrombosis. In the chronic phase, OCT and IVUS were performed and found no residual thrombus and no trace of plaque rupture within the CAE segment. Doppler velocimetry was also performed and found abnormal stagnant only within the ectasic coronary artery as shown in Figure 3D, although FFR was 1.0, which indicated there was no functional ischemia [10]. These findings confirmed that CAE was the most probably source of recurrent coronary thrombosis in this case. Although antiplatelet therapy is generally considered to be effective for the prevention of thrombosis in patients with CAE [2,11,12], this was not sufficient in our case with resultant recurrent myocardial infarction. On the contrary, anticoagulation therapy started at the second event, removed almost all thrombi within one year, although the AV branch remained occluded. Anticoagulation therapy was recently reported to improve the prognosis in patients with AMI [13]. According to that result and our experience, both warfarin and NOAC may be effective to prevent thrombus formation in patients with CAE, although no standard treatment recommendation has not yet been established. CAE can be detected with coronary CT, and follow-up is also possible with magnetic resonance imaging [14,15]. Thus, cardiologists need to pay close attention to the focal coronary thrombus formation due to sluggish blood flow in patients with CAE.

Conclusions

In patients with acute myocardial infarction comorbid with severe coronary artery ectasia, the local thrombus formation due to stagnant local blood flow may become the cause of coronary thrombosis. Anticoagulation therapy may be effective to prevent thrombus formation in patients with CAE, although this treatment has not yet been established as standard therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the medical staff in the South-Miyagi medical center for their cooperation in the present study.

Footnotes

Statement

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Shibata T, Kawakami S, Noguchi T, et al. Prevalence, clinical feature and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction attributable to coronary artery embolism. Circulation. 2015;132:241–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mavrogeni S. Coronary artery ectasia: from aiagnosis to treatment. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2010;51:158–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rab ST, Smith DW, Almurung NB, et al. Thrombptic therapy in coronary ectasia and acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1990;119:955–57. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(05)80338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaMendola CL, Culliford AT, Harris LJ, Amendo MT. Multiple aneurysms of the coronary arteries in a patient with systemic aneurysmal disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49:1009–10. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(90)90892-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papadakis MC, Manginas A, Cotileas P, et al. Documentation of slow coronary flow by the TIMI frame count in patients with coronary ectasia. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:1030–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01984-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorrell VL, Davis MJ, Bove AA. Origins of coronary artery ectasia. Lancet. 1996;347:136–37. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rath S, Har-Zahav Y, Battler AO, et al. Fate of nonobstructive aneurysmatic coronary artery disease: angiographic and clinical follow-up report. Am Heart J. 1985;109:785–91. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoniadis AP, Chatzizisis YS, Gionnoglou GD. Pathognentic mechanisms of coronary ectasia. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130:335–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamura A, Ito H, Iwakura K, et al. Detection of embolic particles with the Doppler guide wire during coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:212–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasula S, Agarwal SK, Hacioglu Y, et al. Clinical and prognostic value of post-stenting fractional flow reserve in acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2016 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309422. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasar AS, Erbay AR, Ayaz S, et al. Increased platelet activity in patients with isolated coronary ectasia. Coron Artery Dis. 2007;18:451–54. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3282a30665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magninas A, Cokkinos DV. Coronary artery ectasias: Imaging, functional assesment a clinical implications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1026–31. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao L, Cao Z, Zhang H. Efficacy and safety of thrombectomy combined with intracoronary administration of tirofiban in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:2699–705. doi: 10.12659/MSM.896703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bluemke DA, Achenbach S, Budoff M, Gerber TC. Noninvasive coronary artery imaging: magnetic resonance angiography and multidetector computed tomography angiography. Circulation. 2008;118:586–606. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mavrogeni SI, Manginas A, Papadakis E, et al. Correlation between magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) in ectasic coronary vessels. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2004;6:17–23. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-120027801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]