Abstract

Veins used as grafts in heart bypass or as access points in hemodialysis exhibit high failure rates, thereby causing significant morbidity and mortality for patients. Interventional or revisional surgeries required to correct these failures have been met with limited success and exorbitant costs, particularly for the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Vein stenosis or occlusion leading to failure is primarily the result of neointimal hyperplasia. Systemic therapies have achieved little long-term success, indicating the need for more localized, sustained, biomaterial-based solutions. Numerous studies have demonstrated the ability of external stents to reduce neointimal hyperplasia. However, successful results from animal models have failed to translate to the clinic thus far, and no external stent is currently approved for use in the US to prevent vein graft or hemodialysis access failures. This review discusses current progress in the field, design considerations, and future perspectives for biomaterial-based external stents. More comparative studies iteratively modulating biomaterial and biomaterial-drug approaches are critical in addressing mechanistic knowledge gaps associated with external stent application to the arteriovenous environment. Addressing these gaps will ultimately lead to more viable solutions that prevent vein graft and hemodialysis access failures.

Keywords: External stents, biomaterials, biocompatibility, biodegradability, mechanical properties

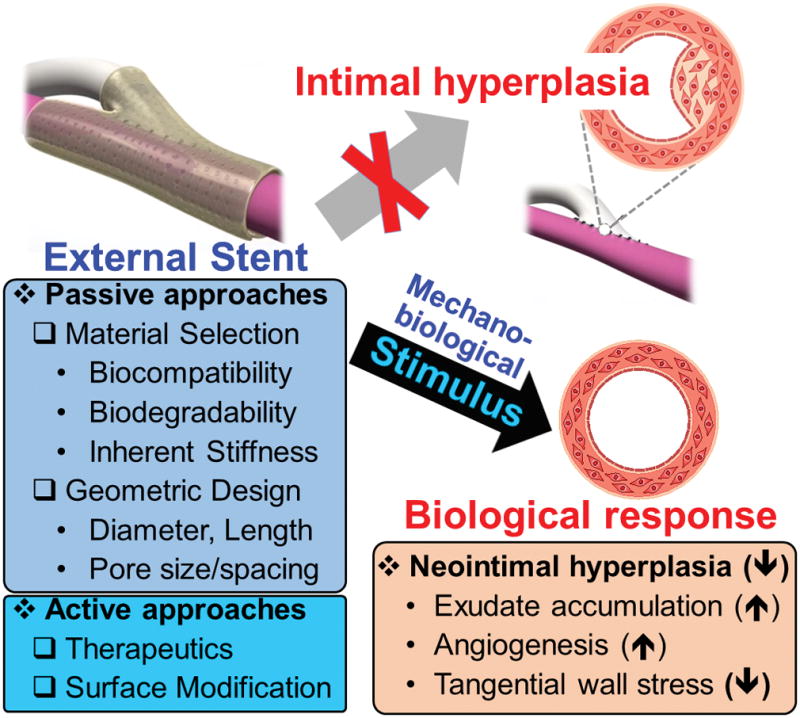

Graphical abstract

External stents provide a promising means to prevent vein graft and hemodialysis access failures. Its ability to do this depends on the material and scaffold design chosen. Physicochemical properties (e.g. chemistry, molecular weight) and scaffold geometry (e.g. diameter, length, pore size and interconnectivity) govern the stent properties (e.g. biodegradation time, mechanical properties) and, ultimately, the biological response that it elicits.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Clinical Problem of Vein Graft and Hemodialysis Access Failure

Vein graft and hemodialysis access failures impose significant morbidity and mortality risks for patients and place a particular financial burden on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as the primary payer for treatments. Autologous saphenous vein grafts (SVGs) are connected to arteries to serve as conduits for bypassing arterial occlusions in approximately 250,000 annual coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and 80,000 peripheral artery bypass grafting (PABG) surgeries, respectively.[1–3] Despite intensive study and some advances in percutaneous techniques such as balloon angioplasty and intraluminal stenting, bypass grafting remains the gold standard for coronary artery disease (CAD) patients and for peripheral artery disease (PAD) patients with severe femoropopliteal lesions.[4] Peripheral artery bypass is also employed in more than 100,000 annual vascular access creation surgeries, where the access site created functions as a portal for hemodialysis in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients.[5] Hemodialysis serves as the primary lifeline for ESRD patients awaiting kidney transplantation. Typically in the arm, a vein-to-artery connection (i.e. arteriovenous fistula (AVF)) effectively creates an access site to the entire bloodstream, allowing a means to filter out toxins in the blood through an external dialyzer. Synthetic expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) arteriovenous grafts (AVGs) are also employed to create access sites in approximately 20% of cases.[5]

Although CABG is considered the gold standard for treating CAD patients with severe occlusions, 10 – 20% of SVGs fail within the first year after surgery, and up to 50% fail within 10 years.[6–10] Similarly, in the lower extremities of PAD patients, 30 – 50% fail within 5 years.[11] The metric for vein graft or hemodialysis access failure is commonly defined as ≥ 70% occlusion of the grafted vessel that necessitates either revision via angioplasty, intraluminal stenting, or other surgical intervention, or replacement due to total graft/access loss.[12, 13] Primary patency is defined as the intervention-free interval following surgery, whereas secondary patency describes the total survival of the graft or access regardless of whether interventional procedures are required to maintain it.[12, 13] Graft failure can lead to disease progression, recurrent angina, myocardial infarction, and death.[5, 14–16] Failures are even more pronounced at hemodialysis access sites. Primary (i.e. intervention-free access survival) and secondary (i.e. access survival until abandonment)[12, 13] patency rates for fistulas are 60% and 71% at 12 months (i.e. 40% failure), and 51% and 64% at 24 months (i.e. 49% failure), respectively. Even worse, PTFE grafts exhibit primary and secondary patency rates of 58% and 76% at 6 months (i.e. 42% failure) and 33% and 55% at 18 months (i.e. 67% failure), respectively.[17–19] This affects the quality and length of life of patients, and also leads to disproportionate financial dispositions for CMS. For example, patients with graft failure are approximately $78,654 more expensive to treat per patient-year, which translates to $1.8 – 2.9 billion in direct costs primarily absorbed by Medicare for the hemodialysis graft population alone.[5]

1.2. Neointimal Hyperplasia

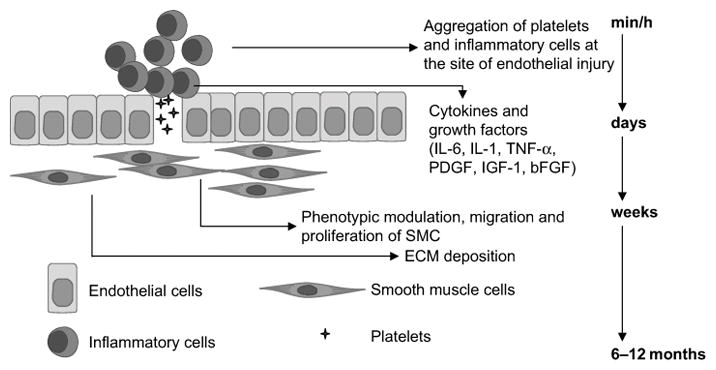

Neointimal hyperplasia (NH), a process in which the intimal layer of the vein wall thickens leading to stenosis and occlusion, is the primary culprit (>70%) for vein graft and hemodialysis access site failures.[1, 20] It is therefore an important process to understand for developing therapies that effectively prevent vein failures. Thrombosis (i.e. clotting) is a typical cause of acute graft failures (within the first 30 days) whereas NH plays a dominant role in early vein failures (1 – 24 months) and contributes to atherosclerosis, the main cause of late-stage graft failures (2 years after surgery). NH is an excessive, pathological venous remodeling process in which myofibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) migrate to the intimal layer and proliferate extensively, subsequently depositing extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins to form a “neointima”.[21] Mitra et al. breaks down NH into five sequential events: 1) platelet activation, 2) inflammation and leukocyte recruitment, 3) coagulation, 4) VSMC migration and 5) proliferation (Figure 1).[22] Transdifferentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, and their subsequent migration and proliferation from the adventitia to the intima, are also involved in NH.[23, 24] Migration and proliferation of VSMCs and myofibroblasts and their deposition of ECM proteins culminates in stenosis of the graft/access that impedes blood flow, leads to disease progression, and increases the risk of adverse cardiac events, other complications, and death.

Figure 1.

Neointimal hyperplasia is triggered by injury at the time of surgery as well as from the high pressure and flow of the arterial environment. Endothelial injury exposes the VSMCs and subendothelial matrix containing tissue factor to the circulating blood, which activates platelets and causes their aggregation. Immune cells such as leukocytes and inflammatory cells are then recruited to the site, and a milieu of cytokines and growth factors are released from these cells. This causes a phenotypic switch in VSMCs that leads to their migration and proliferation into the intima along with myofibroblasts. An excessive amount of extracellular matrix milieu is also deposited into the intima from these migratory cells to form the neointima. Reproduced with permission.[22] Copyright 2006, Nature Publishing Group.

NH occurs as a result of intimal, medial, and adventitial damage to the vein graft before, during, and after surgery. In the case of CABG and PABG, significant endothelial and adventitial damage is also incurred from the vein harvesting process – as early as 4 hours after implantation, the endothelium is either denuded or attenuated with infiltrating inflammatory cells, other cells, and protein constituents present.[2, 25–27] Certain genetic factors, pre-existing NH, and medical conditions such as uremia in ESRD patients leave a patient predisposed to NH.[23, 28–31] During surgery, trauma from suturing damages all three layers of the vein wall.[29, 32] Injury and denuding of the protective endothelium exposes VSMCs directly to blood flow as well as procoagulatant and proinflammatory constituents,[22] while damage to the adventitial vasa vasorum leads to hypoxia and subsequent NH development.[33–35] After surgery, exposure of the vein to an order of magnitude increase in pressure and flow in the arterial circulation causes abnormal distention of the vein, resulting in diameter mismatch between vein and artery, high tangential wall stresses, and low fluid shear stresses[36–39]. The vein walls thicken to normalize tangential shear stress regulated by the ratio of luminal radius to wall thickness.[40] Subsequent turbulent flow, especially around the distal (venous) anastomosis, damages the endothelium.[28, 41] In the case of hemodialysis patients, adventitial injury from repeated needling to perform dialysis and immune/inflammatory responses from PTFE implantation are thought to play a role in NH-mediated stenosis.[23, 29] Percutaneous techniques used to correct the ensuing obstructions in blood flow, namely balloon angioplasty and intraluminal stenting, have been shown to further damage the endothelium, adventitia, and perivascular tissue, thus promoting a proliferative and inflammatory response leading to recurrent stenosis.[42, 43] These procedures add pain and suffering to patients and are expensive, with balloon angioplasty alone adding more than $18,000 per patient-year for hemodialysis graft patients.[44] While placing an intraluminal stent has been shown to increase primary patency of AVGs from 23% to 46% over the first 6 months, 2 year patency remains very low at 9.5% compared to 4.5% for angioplasty alone.[45, 46] Poor clinical results such as those using the current standard-of-care, and the large expenses associated with their ineffective use, indicate the need for better therapies to prevent hemodialysis access and vein graft failure.

1.3. Use of Systemic Delivery of Therapeutics to Reduce Vein Failures

Current medical innovations used to sustain vein graft or hemodialysis access integrity have underperformed relative to desired long-term outcomes. Anti-platelet agents such as dipyridamole with aspirin inhibit thrombotic events and may improve early graft/access patency. In a study following angioplasty revision of SVGs in 343 CABG patients one year-post surgery, Chaser et al. revealed that dipyridamole plus aspirin treatments reduced SVG occlusions from 27% in the placebo to 16%.[7] In AVGs, this same treatment produced a modest, statistically significant improvement in one-year patency compared to the placebo, from 23% to 28%.[47] However, Goldman et al. observed no effect on SVG patency 1 – 3 years post-CABG from these treatments,[48] and some studies have observed no benefit for SVGs of PABG patients.[49, 50] Some modest benefits of lipid-lowering agents (e.g. statins) on long-term SVG patency have been observed; a 1351 patient, 7.5 year Post CABG Trial revealed that moderate and aggressive administration of lipid-lowering drug lovastatin reduced revascularization procedures by 24% and 30%, respectively.[51] A 172 patient study demonstrated improved secondary patency of SVGs in PABG after 2 years with statin treatment (97% vs. 87% control),[52] but Pisoni et al. showed no improvement from statins in fistula or graft outcomes in a 601 hemodialysis patient study.[53] Antiplatelet agents and lipid-lowering drugs generally help and are part of the current CABG treatment paradigm,[54] but should not be considered “game-changers” on their own given the significant patency issues still reported with their administration.[36]

Cell cycle regulation is another possible approach to prevent NH. In a large 1,404 patient study, an edifoligide oligonucleotide acting as a transcriptional cell cycle regulator of proliferation exhibited no patency benefit.[55, 56] This lack of efficacy despite drug functionality against a known NH target may suggest that sustained, localized release is required to make an impact. A one-time, localized application to the external surface of AVFs or AVGs with an aqueous solution containing vonapanitase (PRT-201®, Proteon Therapeutics), a recombinant human elastase that degrades elastin fibers to prevent NH, is one approach that has shown some promise to improve hemodialysis access patency and is currently in Phase III clinical trials.[57, 58] A plethora of other gene and drug delivery-based approaches have been investigated on the pre-clinical level and can be reviewed elsewhere.[59] In general, they aim to inhibit inflammatory, hypoxic, fibrotic, proliferative, or migratory processes correlated with NH formation, or they promote vascularization to minimize hypoxia-induced effects. While positive effects have been observed in many of these animal models and in some clinical trials, the fact remains that there is no drug currently used on the market that effectively prevents vein graft or hemodialysis access failures on its own.

2. External Stents

2.1. Seminal Studies of External Stenting

As vein graft disease is also defined by mechanical failures and drugs have not shown a great efficacy in preventing long-term failures, the biomedical community inquired if use of mechanical supports could reduce NH via external stents or sheaths comprised of a variety of materials. Parsonnet et al. became the first to apply external sheaths around vein grafts in 1963; their team observed that external sheaths comprised of knitted monofilament polypropylene fibers prevented over-distention of vein grafts and integrated into the host perivascular tissue in an end-to-end jugular vein-to-common carotid artery canine model.[60] The authors speculated that by preventing over-distention, the diameter of the vein could better match that of the artery and reduce turbulence that leads to thrombosis. Using the same canine model in 1978, Karayannacos et al. became the first to observe that an external mesh around a vein could reduce NH by preventing dilation of the vein graft.[61] Given that the loose-fitting Dacron (poly(ethylene terephthalate)) meshes promoted a higher degree of neovasa vasorum and less intimal-medial thickness than a tightly woven Dacron sheath, the authors deduced that Dacron meshes reduced NH by promoting formation of neovasa vasorum that minimize ischemic conditions inducing VSMC proliferation. Going off of subsequent studies demonstrating the positive effect of constrictive meshes on jugular vein grafts to protect endothelium[62] and reduce cross-sectional wall area, VSMC volume, and matrix deposition compared to loose wraps,[63] Violaris et al. discovered that pig saphenous vein-to-carotid artery grafts constricted with a tight-fitting (4 mm diameter) PTFE graft had lower luminal cross-sectional area and greater NH, with only the media thinner.[64] This implied to the authors that restricting the ability of SVGs to distend may damage the adventitia and ultimately be disadvantageous. Following this result, Angelini et al. applied a nonrestrictive (6 mm diameter), highly porous Dacron stent helically wound with polypropylene in the same pig model.[65] Four weeks after implantation, the authors discovered that the lumen was larger, while the intima and media were almost four-fold thinner than the paired unstented control SVGs. Seeking to determine the ideal fit around the vein grafts, Angelini’s team discovered in the same pig model[66] that the oversized (8 mm diameter) mesh performed better than the nonrestrictive (6 mm) mesh used earlier[65], and both of these sizes were superior to the mildly restrictive (5 mm) mesh in terms of both total wall thickness (in order of reducing diameter: 81%, 66% and 40% reduction compared to untreated control) and neointimal thickness (72%, 62% and 0% reduction for 8 mm, 6 mm, and 5 mm, respectively).[66]

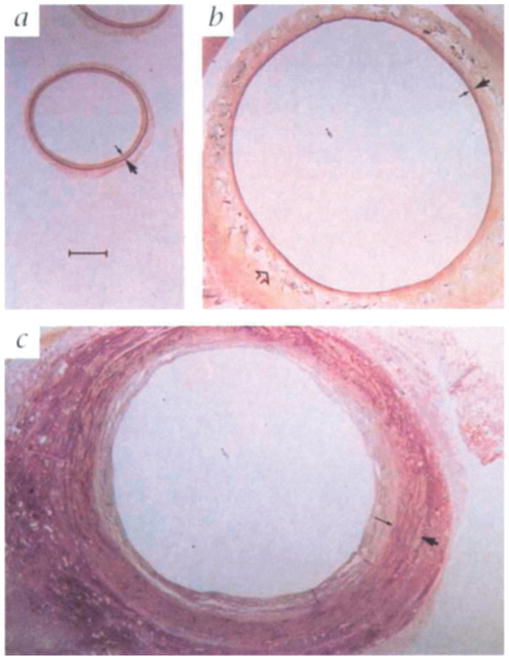

Based on these findings, Mehta et al. applied the 8 mm Dacron mesh design to examine the underlying mechanism and long-term impact of external stent implantation in pigs.[67] Compared to unstented controls, treated SVGs resulted in a significant reduction in intimal (93%) and medial (75%) thickness after 6 months (Figure 2). This correlated with decreases in cell proliferation in the intima and media of the stented grafts, as the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) index of the unstented grafts were 18.7 and 3.9, respectively, compared to zero for both in the stented group (Figure 3A – B). PDGF, a potent mitogenic and chemotactic regulator of VSMCs,[68] was also significantly attenuated by 38 – 50% overall in the stented group at both 1 and 6 months (Figure 3C – F). Positive staining for endothelial cells by Dolichos bifluorus agglutinin (DBA) (Figure 4) and proliferating cells by PCNA (Figure 3A – B) in the adventitia of the stented group after 6 months indicates neovasa vasorum growth that is largely absent in the unstented grafts.

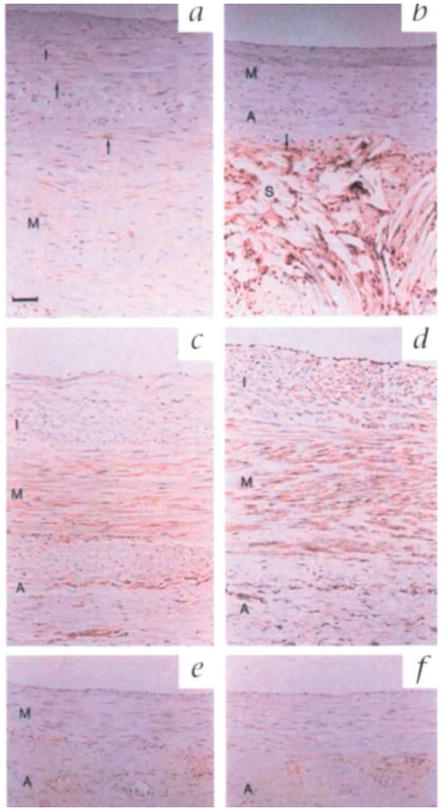

Figure 2.

Histological sections from a) the ungrafted vein (negative control) compared to vein grafts 6 months after surgery that were either b) wrapped with an 8 mm Dacron external stent or c) unwrapped (positive control). Small arrows point out the internal elastic lamina defining the intimal-medial line, while the large arrow points out the external elastic lamina defining the boundary between medial and adventitial layers. Pronounced intimal and medial thickening in the untreated control is largely absent in the stented graft. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 1998, Nature Publishing Group.[67]

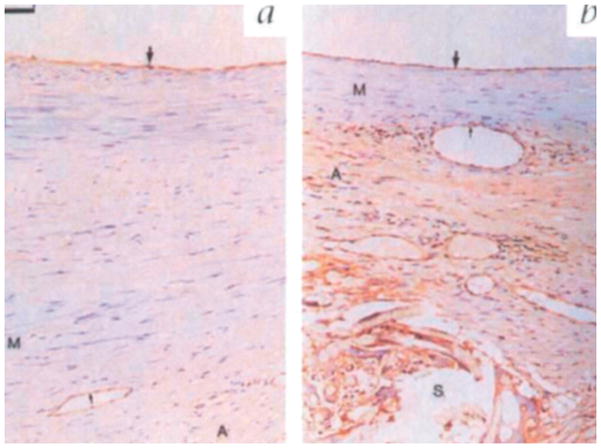

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in a) an unstented and b) a stented graft after 6 months. Marked brown nuclear staining is present in the adventitia but not the media of stented grafts, indicating significant adventitial proliferation forming the neoadventitia. Immunohistochemical staining for total PDGF protein (brown staining) in unstented grafts after c) 1 month and d) 6 months compared to stented grafts at e) 1 month and f) 6 months reveals increased PDGF staining in the untreated group, indicating extensive proliferation in the adventitia of stented grafts. Scale bars in a) and c) apply to the entire panel and represent 50 μm. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 1998, Nature Publishing Group.[67]

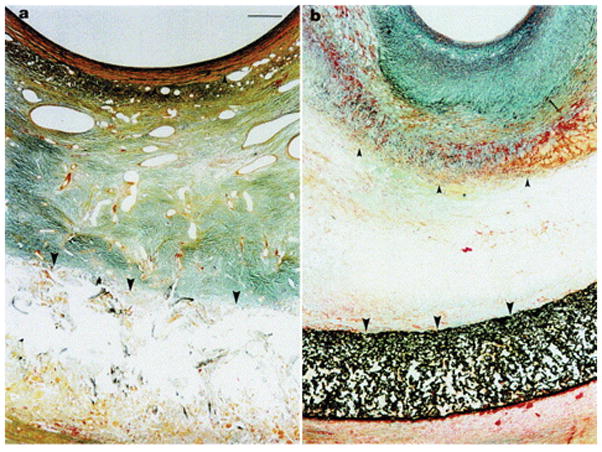

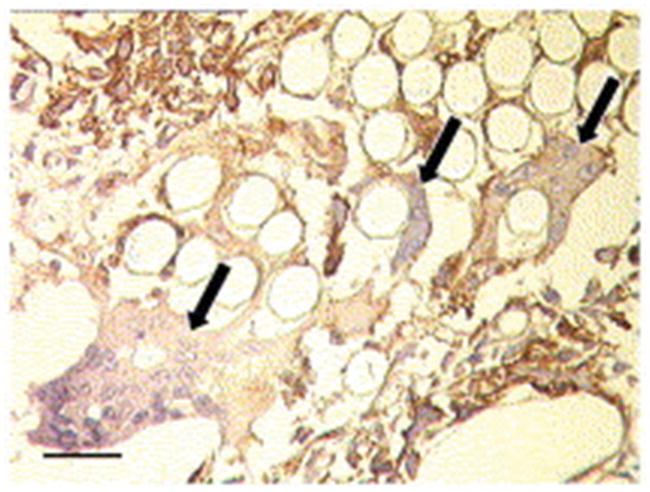

Figure 4.

Dolichos bifluorus agglutinin (DBA) staining demonstrating an intact luminal endothelium (large arrow) in both a) unstented and b) externally stented grafts after 6 months. Pronounced brown cytoplasmic staining in the adventitia of stented grafts indicates the presence of endothelial-lined vessel growth comprising a neoadventitia. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 1998, Nature Publishing Group.[67]

To understand the role of pore size on NH, the 8 mm macroporous Dacron mesh and an 8 mm microporous PTFE were implanted in the same pig model[69]. One month after surgery, pig SVGs treated with the macroporous stents exhibited a greater reduction in NH (Figure 5) that accompanied an increase in adventitial microvessel growth (Figure 6) and a decrease in PDGF expression and cell proliferation, suggesting the need for macroporosity. Further mechanistic insights were gleaned in 2002 from a hypocholesterolemic pig model to better mimic vascular disease conditions.[70] After 3 months, mesh-mediated reductions in SVG NH correlated with significant reductions in graft cholesterol concentrations and atheroma markers, as well as vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) in the absence of atheroma precursor foam cells. This suggested that the macroporous Dacron stent can potentially inhibit both NH and atherosclerosis.

Figure 5.

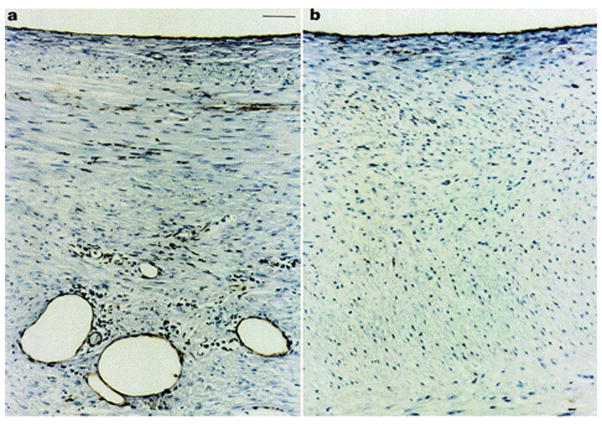

Trichrome staining of porcine SVGs after one month wrapped with a) an 8 mm loos-fitting macroporous Dacron stent and b) an 8 mm loose-fitting microporous PTFE. The internal elastic lamina marked by small arrows and the external elastic lamina marked by large arrows clearly shows a large reduction in NH with the macroporous Dacron stents compared to the PTFE stent. The neointima in the PTFE-wrapped SVGs is highly collagenous, as indicated by the green-blue staining. Orange/brown staining represents VSMCs. There are large, abundant microvessels present in the Dacron-treated grafts, whereas the microvessels in b) are clearly absent, with no large microvessels outside the stent. Scale bare in a) applies to b) as well, and represents 50 mm. Reproduced with permission.[130] Copyright 2001, Elsevier.

Figure 6.

Endothelial staining with lectin A demonstrates a marked increase in microvessels present in the adventitia of a) the macroporous Dacron stent, while b) this is absent in the microporous PTFE stent. Scale bare in a) applies to b) as well, and represents 50 mm. Reproduced with permission.[130] Copyright 2001, Elsevier.

2.2. Disappointing Clinical Trials with Dacron Meshes

Although these results are informative and promising, the first external Dacron stent clinical trial ended tragically, and a subsequent trial in 2011 using a different Dacron stent (ProVena®, B. Braun) (Figure 7) to reinforce varicose or ectatic vein grafts in PABG patients demonstrated no patency benefit 24 months after surgery (Table 1).[71] In the 2007 Extent study, an external Dacron stent reinforced with PTFE ribs spaced 1 cm apart (Extent®, Vascutek Inc.) (Figure 8) was implanted over the SVGs of 20 CABG patients, resulting in thrombosis for every patient within 6 months.[72] The authors were transparent that these failures could be the result of fatal miscalculations in the material selection or scaffold design that render inappropriate mechanical strength (e.g. too rigid or too soft), stent-to-vein spacing (e.g. under or oversizing), or unforeseen complications (e.g. kinking of the graft). It is therefore prudent to consider and understand the function and tradeoffs of each component of the external stent design at the research stage in order to avoid making such costly mistakes in the clinic, beginning with the material selection. Alteration of external stent properties by material selection, mesh type (e.g. knitted, warp-knitted, woven, nonwoven, electrospun, ablated sheets)[73] or geometric design can be considered “passive” approaches to stent design, whereas incorporation of therapeutic agents and/or surface modifications can be described as “active” design approaches (Figure 9). By mastering passive design approaches, first-generation therapies can be created that effectively prevent vein graft or hemodialysis access failure with the possibility of lower regulatory hurdles relative to drug alone or drug-device combination products. The opportunity then exists to improve upon these initial methodologies with later generation products that incorporate active approaches.

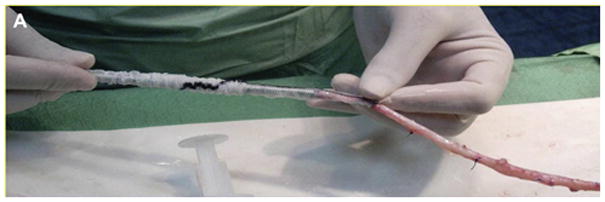

Figure 7.

Wrapping of the saphenous vein to bypass between superficial femoral to posterior tibial artery with ProVena®, a macroporous Dacron mesh. Reproduced with permission.[71] Copyright 2011, Elsevier.

Table 1.

Recent Clinical Trials Utilizing External Supports and/or Localized Therapeutics

| Technology | Intended use, Reference (Year) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Dacron reinforced with PTFE ribs spaced 1 cm apart (Extent®, Vascutek Inc.) | Saphenous vein grafts of CABG patients, Murphy et al. (2007).[72] | Thrombosis observed in all 20 CABG patients within 6 months. |

| Dacron mesh with 750 μm pores (ProVena®, B. Braun) | Varicose or ectatic vein grafts utilized in peripheral bypass patients, Carella et al. (2011).[71] | Safety demonstrated in initial trial, but no patency benefit observed in 21 treated patients compared to untreated control group. |

| Nitinol mesh (eSVS Mesh®, Kips Bay Medical) | Saphenous vein grafts in CABG patients, Emery et al. (2015).[119] | Clinical trial terminated in September 2015 due to low patency rates |

| Braided Phynox mesh (Fluent®, Vascular Graft Solutions) | Saphenous vein grafts of CABG patients, Taggart et al. (2015).[114] | Reduced intimal hyperplasia, less ectasia, and more lumen uniformity observed after 1 year in 30 patient trial. |

| Nitinol mesh (VasQ®, Laminate Medical) | Arteriovenous fistula anastomoses, Chemla et al. (2016).[118] | Adequate safety with high maturation and patency rates observed after 6 months in 20 patient trial. |

| Replication-deficient adenoviral vector expressing a VEGF-D gene localized to the anastomosis with a collagen collar (Trinam®, Ark Therapeutics Group) | Arteriovenous graft (PTFE-vein) anastomoses of hemodialysis patients, Fuster et al. (2001).[145] | Phase III trial was terminated due to “strategic reasons” in November 2010. |

| Collagen gel loaded with allogenic endothelial cells (Vascugel®, Shire Pharmaceuticals) | Arteriovenous graft or fistula anastomoses of hemodialysis patients, Conte et al. (2009).[146] | No patency benefit demonstrated in two Phase II clinical trials, one of these studies was terminated in October 2014. No longer an active program at Shire. |

| Nonbiodegradable ethylene vinyl acetate wrap eluting paclitaxel (Vascular Wrap®, Angiotech Pharmaceuticals) | Arteriovenous graft (PTFE-vein) anastomoses in hemodialysis patients. Initially applied to PTFE-vein anastomoses of patients undergoing peripheral bypass surgeries, Mátyás et al. (2008).[147] | Phase III clinical trial terminated in April 2009 due to a higher infection rate in the treated group, with no demonstrated patency benefit. Initial trial in peripheral bypass patients showed lower amputation rates in treated group. |

| Sirolimus-eluting collagen membrane (Coll-R®, Vascular Therapies) | Arteriovenous graft or fistula anastomoses of hemodialysis patients, Paulson et al. (2008).[148] | Safety and technical feasibility demonstrated in Phase I/II trial. Currently recruiting patients for Phase III trial. |

Figure 8.

Extent®, a macroporous Dacron sheath reinforced with PTFE ribs. The flange permitted placement after completion of both anastomoses. Reproduced with permission.[72] Copyright 2007, Elsevier.

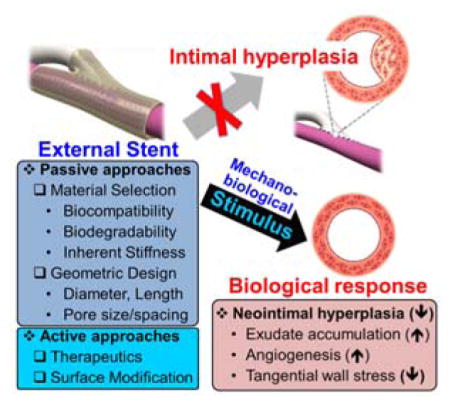

Figure 9.

External stents have demonstrated an ability to reduce neointimal hyperplasia by promoting exudate accumulation in the interstitial space between the graft and stent, promoting adventitial angiogenesis, and reducing tangential wall stress. The external stent design should be carefully considered to maximize vein graft and hemodialysis access patency. Passive design approaches take into account material selection and device geometry. Active approahces incorporate therapeutics and/or modify the surface to change the bioactivity of the external stent.

3. Design Considerations for External Stenting

3.1. Passive Approaches – Material and Geometric Design Considerations

3.1.1. Seminal Studies Shifting from Nondegradable to Biodegradable External Stents

The type of material selected will influence the biodegradability, biocompatibility, and mechanical properties of the device, among other considerations.[74–76] Like the other materials used as external sheaths at the turn of the 21st century such as Nitinol[77–79] and Phynox (a wrought Cobalt-Chromium-Nickel-Molybdenum-Iron Alloy)[80–83] metals or polymers such as polypropylene[60] or ePTFE,[63, 84–88] Dacron is nonbiodegradable. This is of concern because long-term implantation of nondegradable material carries a greater risk of infection, chronic inflammation, and/or compliance mismatches at different interfaces.[89–96] In contrast, hydrolytically degradable polyesters such as polyglactin (PGA) and poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), natural polymers (e.g. collagen or hyaluronic acid), or combinations thereof meet this criterion in addition to exhibiting good biocompatibility.[76] In 2004, Jeremy et al. and Vijayan et al. became the first researchers to employ a biodegradable material for external stenting of SVGs (Figure 10).[91, 92] In two separate studies, they demonstrated the ability of a PGA sheath to prevent neointimal and medial thickness in a bilateral saphenous vein-to-common carotid artery interposition graft model.[91, 92] Not only was there an effect in the one month following surgery when the PGA device was still intact,[91] but also well after its presumed 60 – 90 day degradation period[97, 98] at 6 months.[92] An abundance of inflammatory cells such as macrophages and giant cells, as well as endothelial cells, VSMCs, and microvessels in and around the material, were observed at both 1 and 6 months (Figures 11 – 13). These cells, particularly the macrophages and giant cells, accelerate degradation of the scaffold. The authors also postulated that the battery of chemokines and growth factors released by these cells could help to attract VSMC migration towards the external stent instead of the intima while simultaneously spurring angiogenesis that prevents hypoxia (Figure 14). However, it stands to reason that a careful balance of this phenomena should be reached, as the authors concede that such an intense biological response as that seen at 6 months is partially fibrotic and can lead to encapsulation of the scaffold with fibrotic tissue[92] that could result in complications for a patient.[99, 100] A strong inflammatory response could also trigger NH and/or thicken the vessel enough that hypoxia-induced NH becomes an issue.[34, 35, 59]

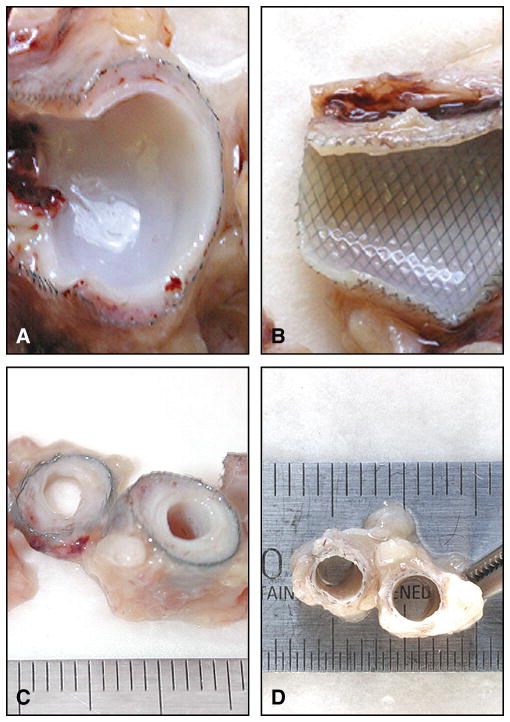

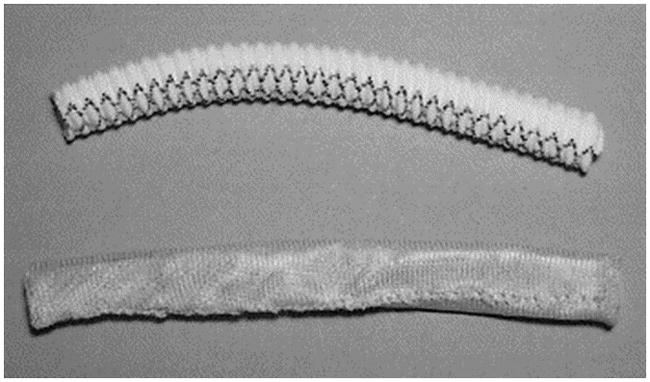

Figure 10.

A Dacron external sheath (top) as compared to polyglactin sheath from Vascutek Ltd (bottom). Both are 8 mm in diameter. Reproduced with permission.[91] Copyright 2004, Elsevier.

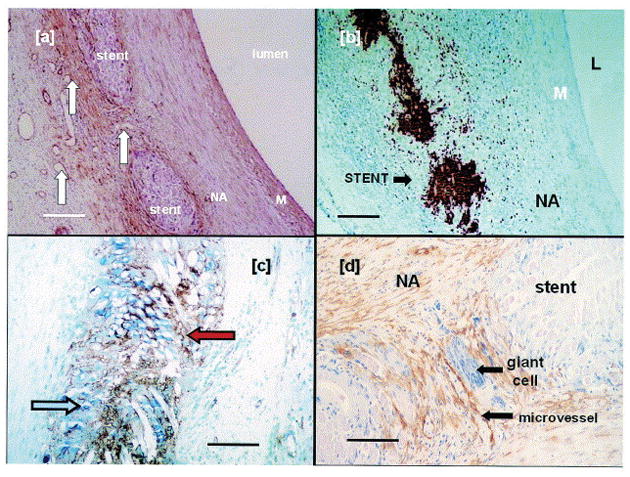

Figure 11.

Photomicrographs of pig SVGs fitted with an 8 mm PGA external stent after one month. In and around the PGA sheath, there is a high density of a) microvessels (white arrows), b) macrophages as revealed by immunostaining for MAC387, c) endothelial cells (blue arrow) and proliferating cells (PCNA positive, red arrow). Immunostaining for d) α-actin (brown) and giant cells (purple) reveals that VSMCs and giant cells have also accumulated in the interstitial space. In contrast, microvessels, macrophages, endothelial cells, and proliferating cells are largely absent in the media of the graft. Scale bar for 100 μm for a) and b), and 50 μm for c) and d). Reproduced with permission.[91] Copyright 2004, Elsevier.

Figure 13.

A PGA external stent fitted around pig SVGs after one month demonstrates multilobed giant cells (arrows) with dark blue nuclei located within the interstitial space. Reproduced with permission.[92] Copyright 2004, Elsevier.

Figure 14.

Schematic illustrating the main events stipulated to be responsible for the ability of external stents to reduce NH. First, an exudate forms in the interstitial space between the graft and sheath. The fibrin-rich exudate may trigger adventitial angiogenesis and promote cell migration. Second, macrophage and giant cell infiltration creates a chemotactic gradient, promoting VSMC migration from the media to the sheath. As endothelial cells are also drawn to the external stent by chemotaxis, they can act as building blocks along with VSMCs to promote neovasa vasorum formation. The neovasa vasorum is then further promoted by the battery of angiogenic factors that are secreted by the infiltration macrophages and giant cells. Reproduced with permission.[129] Copyright 2007, Elsevier.

3.1.2. Bodily Response to Implantation

Like any other implant, implantation of an external stent around the vein results in some degree of injury to the surrounding tissue that perturbs homeostasis and results in a complex wound healing response.[74] As alluded to earlier, the intensity and duration of this inflammatory response may play an important role in the function of the external stent and defines the biocompatibility of the device. Physicochemical and geometric properties of the external stent partially govern this response, which is characterized by the degree of acute inflammation, chronic inflammation, granulation tissue formation, foreign body reaction, and fibrosis.[74] The foreign body reaction, comprised of foreign body giant cells and granulation tissue (i.e. macrophages, fibroblasts, capillaries), is a critical step in the type of biological response elicited and is highly dependent upon the topology and surface chemistry of the implant. These properties mediate the type and quantity of proteins adsorbed on the surface of the substrate, which provide ligands for monocyte or macrophage attachment and may also signal the macrophage fusion process that generates foreign body giant cells.[74]

It is unclear what degree of inflammation and foreign body reaction is ideal for external stenting. However, it has been shown that complement and mast cells migrate onto NH-reducing macroporous polyester sheaths and deposit ECM proteins. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, giant cells, and T-cells were shown to be entrapped by these sheaths,[69] but not with the ineffective microporous ePTFE stents.[61, 101] In general, substrates with higher surface area-to-volume ratios such as porous materials exhibit higher ratios of macrophages and foreign body giant cells, whereas smooth surfaces with low surface area-to-volume ratios exhibit a significant degree of fibrosis. From this perspective, porous substrates may be preferable to nonporous or less porous ones as fibrosis is intrinsically linked to NH,[100] but a balanced response is desired for a normal wound healing process to occur.[73] As meshes tend to be highly porous, comparative studies in the hernia repair environment have shown that the foreign body reaction is fairly uniform regardless of mesh type, but different raw materials affect the extent of the reaction.[73, 102] Studies comparing inflammatory responses between different materials are limited. In one such study, Dacron meshes exhibited the greatest foreign body reaction and chronic inflammatory response compared to ePTFE and polypropylene meshes in a mouse subcutaneous implantation model.[103] Meanwhile, ePTFE meshes were encapsulated with fibrotic tissue, exhibiting a significant amount of fibrosis at 12 weeks. Of the three materials compared, polypropylene exhibited the greatest biocompatibility, with less fibrosis and foreign body reaction. Coating polypropylene with a rapidly degrading material such as polyglactin increased inflammation after 40 days in a rat abdominal wall implantation model,[104] supporting the notion that degradation products elicit inflammatory responses. Of course, the nature of these degradation products and the rate by which the polymer is degraded will influence the type of inflammatory response observed. The nature of degradation products is determined by the material selected, whereas the rate of degradation is also influenced by the polymer’s molecular weight, crystallinity, and porosity.[75, 105] In concert with studies that elucidate optimal inflammatory responses for external stenting, biocompatible, biodegradable materials can be devised that minimize NH and vein failures by promoting some degree of adventitial angiogenesis and meeting other axiomatic criterion.

3.1.3. Choosing Biomaterials Based on Biodegradation Timescale

Fundamentally, implanted materials should not evoke a toxic or sustained inflammatory response and should have a degradation profile and mechanical properties that match the adaptive needs of the vein in the arterial circulation.[76] While the critical adaptive period of vein grafts is not exactly known and may vary depending on the patient, vein wall thickening has been shown to continue for over 12 weeks into arterial exposure in a rabbit jugular vein-to-carotid artery model.[106] Although further study may be required to verify whether wall kinetics in CABG, PABG, and ESRD patients precisely resemble this timeline, this suggests that a sheath should remain relatively intact for at least 3 months. PGA loses its strength when hydrolyzed over 1 – 2 months, as well as polydioxanone (PDX),[75] and therefore may not be ideal materials through the completion of vein remodeling around 3 months. Mechanical integrity is not an issue for nondegradable materials such as Dacron or metals but, as previously discussed, these types of implants carry a greater risk of infection, compliance mismatches, or other complications. Materials that degrade more slowly than PGA may provide a happy medium between biodegradability and mechanical integrity. For example, copolymers of PGA (85/15 poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)) and PDX (50:50 poly(dioxanone-co-cyclohexanone) (PDS)) degrade over 5 – 6 months,[76, 107] which may be a sufficient amount of time to provide mechanical support. On the other hand, PCL degrades very slowly (2 – 3 years), and since some studies suggest degradation can act as a chemoattractant for external migration of VSMCs,[91, 92] it may be desirable to reduce the degradation time. This can be done with a 75/25 poly(ι-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) (P(LA/CL) copolymer that has approximately 95% of its mass remaining 3 months after rat implantation.[108] The potential of these approaches for external stenting has not been extensively explored.[109–111] Recently, Sato et al. examined 6 – 12 month patencies in 24 canine femoral vein-to-femoral artery interposition grafts reinforced with either a loose (8 mm) 75/25 poly(ι-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) (P(LA/CL)) mesh, a nonabsorbable stent, or no stent (control).[111] The 6 – 12 month patencies for the P(LA/CL)-treated grafts (100%) were significantly better than both the nonabsorbable stent group (72.2%) and control groups (63.6%) despite the absorbable and nonabsorbable groups exhibiting equivalent NH reduction relative to control. The authors speculated that the more variable luminal perimeters and intimal-medial thicknesses for the nonabsorbable group may suggest that compliance mismatches played a role in the lower patency rates for this group. Follow-up studies examining potential flow disturbances will be needed to verify this claim.

3.1.4. Type and Amount of Mechanical Support Provided by External Stents

Another important consideration for an external stent is the amount of mechanical support that it provides to the thin, compliant venous walls in the high pressure, high flow arterial environment. Preventing overdistention of the vein was hypothesized in early studies as one way to avert structural collapse by limiting turbulence caused by diameter mismatches between vein and artery.[60–63] Upon examination of several mechanical factors involved in wall thickening in canine autogenous vein grafts, Dobrin et al. observed that intimal and medial thickening associated most with low fluid shear stress and distention, respectively.[40] Likewise, Kohler et al. postulated that external supports preventing distention limit wall thickening because these hyperplastic responses are regulated in part by tangential wall stress - the ratio of luminal radius to wall thickness.[63] However, Violaris et al. showed in a pig SVG model that constrictive 4 mm PTFE external stents lowered the luminal cross-sectional area and increased NH despite medial thinning, which may compromise blood flow through the graft.[64] Comparing pig SVG responses to 4, 6, and 8 mm Dacron sheaths, Izzat et al. demonstrated that loose-fitting Dacron meshes 8 mm in diameter exhibit the greatest attenuation of NH.[66] Since this time, numerous studies have adopted these findings to show the positive effects of loose-fitting external meshes to improve patencies and reduce NH.[67, 69, 70, 91, 92, 111] In these studies, the luminal area of stented grafts tended to increase to areas close to that of the carotid artery that it was replacing. Although some unstented grafts dilated while others did not relative to treated grafts, untreated grafts were consistently far thicker in terms of total wall thickness, with more NH and luminal encroachment. External stents did not suppress or restrict dilation, as the total cross-sectional areas (luminal + wall) were similar between untreated and treated grafts, but did promote interstitial adventitial growth between the graft and stent. Taken together, these observations imply that the adventitial growth promoted by external stenting may absorb some of the wall stresses experienced by the vein. The role of the neoadventitia in reducing wall tension may help explain why both constrictive metal meshes[77–79, 82, 83, 112–114] and loose-fitting polymeric approaches promoting adventitial angiogenesis can reduce NH. Metal based approaches have been shown to reduce wall tension, asymmetric wall thickening, and turbulence without promoting vascularization,[78, 82, 83, 112–117] but may ultimately suffer from fibrotic responses (Figure 15) and tissue buckling or kinking.[77] Although there is some promise with ongoing clinical trials utilizing a braided Phynox mesh (Fluent®, Vascular Graft Solutions)[82, 114] to support vein grafts in CABG and a Nitinol mesh to support fistulas for hemodialysis patients (VasQ®, Laminate Medical),[118] a recent clinical trial reinforcing vein grafts in CABG with a Nitinol mesh (eSVS Mesh®, Kips Bay Medical) was terminated due to lower patency rates. It is possible that this also may have been due in part to tissue buckling or kinking.[119, 120]

Figure 15.

Macroscopic comparison of vein grafts 6-weeks after baboon infrainguinal bypass supported by 6.7 mm meshes (left, a and c) and more constrictive 3.3 mm meshes (right, b and d). Fibrosis and NH are rampant in the less constrictive meshes, while NH is suppressed from the 3.3 mm ones. Reproduced with permission.[77] Copyright 2008, Elsevier.

Superior biocompatibility, biodegradability, and flexibility warrant further studies that examine the mechanical impact of adventitial growth from polymeric external stenting, and how these variables might govern wall remodeling. Moreover, the diameter of the device is not the only factor involved in the type of mechanical support that is provided. The inherent stiffness and biodegradability of the material, type of mesh (e.g. knitted, warp-knitted, woven, nonwoven, electrospun, ablated sheets),[73] thickness,[121, 122] and porosity[123–126] all factor into the mechanical support that it imparts. For example, reducing the thickness and increasing porosity limits stiffness and increases flexibility. Few studies to date have examined the influence of other variables besides device diameter on mechanical support and its ultimate effect on venous responses, hemodynamics, and graft patency.

3.1.5. Role of Pore Parameters on the Effects of External Stenting

Pore size, porosity, and pore spacing (i.e. interconnectivity) clearly impact the mechanical properties of an external stent; greater void space from larger and more interconnected pores means less mechanical force applied to expanded venous tissue unless other properties are simultaneously altered such as mesh type and thickness. Pore parameters also affect the surface area-to-volume ratio and topology of the external stent, and play a large role in the extent of inflammatory reactions observed.[73, 125, 127] As previously discussed, the degree and duration of inflammation influences anti-neointimal angiogenic and chemoattractant responses.[128, 129] The positive effects observed from neoadventitial vascularization and accumulation of chemoattractants within the interstitial space between polymeric supports and venous tissue suggests that pore designs should be implemented that promote these characteristics to some degree. Few studies have directly examined the effect of an external stent’s pore size on neoadventitial growth and NH, and analysis is made difficult by the fact that pore sizes of the meshes used are often unspecified. George et al. observed that external macroporous (presumably 750 μm diameter like ProVena®) Dacron sheaths helically wound with polypropylene significantly reduced NH relative to microporous PTFE stents after one month in a porcine saphenous vein-to-carotid artery interposition graft model.[130] This reduction in NH was accompanied by an increase in adventitial microvessel growth and a decrease in PDGF expression and cell proliferation. However, the analysis from this study is complicated by the fact that two different materials, Dacron and PTFE, were used to compare effects of pore size. These materials bestow different mechanical and immunogenic properties. For example, Dacron exhibits a greater foreign body reaction and more chronic inflammation, while PTFE exhibits a significant amount of fibrosis.[73, 103] Future studies should isolate the effects of pore size by utilizing the same material.

It is difficult to determine what pore sizes are ideal for an external stent’s ability to reduce NH and maintain patency without controlled studies isolating influences of the material and other parameters. It is generally accepted that pores and interconnections must be larger than 50 – 100 μm to promote blood vessel ingrowth, cell invasion, and enhanced biological responses without filling the pores with scar tissue.[73, 131, 132] In general, larger pores exhibit less scarring, inflammatory infiltrate, and connective tissue.[73, 133, 134] However, pore size requirements will differ depending on the material selected as well as the tissue environment where it is applied. For example, polypropylene requires pores larger than 1 mm while pores smaller than 650 μm are adequate for PVDF to obviate scarring between pores in abdominal wall hernias.[135] To enhance bone tissue formation by vascularization, pore sizes greater than 300 μm are recommended.[136, 137] Complicating matters further, when most studies vary one pore variable, another is changed. For example, no significant differences in vascularization or bone tissue ingrowth were detected over 8 weeks for PCL scaffolds (pore sizes of 350, 550, and 800 μm), but Roosa et al. admitted that simultaneous changes in porosity between the groups may have influenced the results.[137] In light of these compounding factors, Bai et al. varied pore size while holding both interconnectivity and porosity constant.[132] In a rabbit model, β-tricalcium phosphate (TCP) cylinders with pores greater than 400 μm (i.e. 415, 557, and 632 μm) implanted into the fascia lumbodarsalis exhibited far more neovascularization than the 337 μm scaffolds.[132] More studies like this are needed with external supports in the venous environment to properly isolate variables and engineer supports that optimize mechanical, biological, and hemodynamic effects.

3.1.6. Localization and Length of External Support

External stents should be designed that properly support veins and grafts in the areas most prone to failure, namely, directly around and adjacent to the distal (venous) anastomosis. Approximately 60% of stenoses in ePTFE hemodialysis grafts occur at or within 1 cm of the venous anastomosis, with another 4 – 29% at the proximal (arterial) anastomosis.[30] Venous injury from surgical trauma, compliance mismatches between the artery, vein, and/or graft,[96] and powerful, pulsatile arterial flow at the irregularly-shaped end-to-side geometry of the anastomoses gives rise to intense wall shear stress gradients and complex turbulent flow conditions (Figure 16).[138] This ultimately leads to significant NH at the shoulder and cushioning regions of the venous anastomosis, [139] which yields more drastic wall shear stress gradients and turbulent flow conditions that cause more NH in a vicious cycle.[140, 141] Few, if any, external stents today have been engineered to stop this vicious turbulence-induced NH cycle by effectively reducing compliance mismatches, tangential wall stresses, and asymmetric wall thickening. Trubel et al. demonstrated that sheep vein grafts wrapped with 8 mm Dacron meshes increased NH at the venous anastomosis with an approximately 2.5-fold increase in NH at this location compared to unstented controls.[142] This indicated to the authors that these meshes should not be applied at the anastomosis, and may be the result of encompassing this region asymmetrically.[129] Similarly, it was advised after poor patency results in clinical trials[120, 143] that the constrictive Nitinol eSVS mesh not be applied to the anastomoses as it could restrict the blood flow through the graft.[144] A different Nitinol design, VasQ®, was devised by Laminate Medical to more easily fit around the venous anastomosis of hemodialysis fistula patients. Early clinical trials demonstrated adequate primary patency of 79% at 6 months for 20 patients[118] compared to historical levels of 60% at 12 months.[18] Although VasQ® still needs to go through significant clinical trials to become available in the US, it highlights how practical considerations related to surgery time, ease of use, and avoidance of injury from surgical implantation should be incorporated in designs to make wrapping around the critical venous anastomosis a more straightforward and beneficial process than in the past. The optimal geometry and length to achieve desirable biological and hemodynamic responses is still unclear and may vary depending on the material selected.

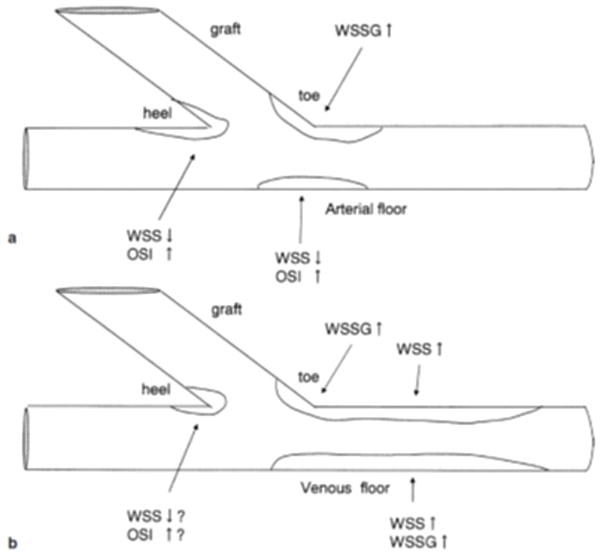

Figure 16.

The spatial distribution of NH a) in SVGs from CABG and b) in AVGs. WSS denotes wall shear stress, WSSG represents the WSS gradient, and OSI is the oscillatory shear index (i.e. the amount of turbulence). Reproduced with permission.[39] Copyright 2003, Springer.

3.2. Active Approaches – Applying Therapeutics to the Adventitia to Reduce Vein Failures

3.2.1. Rationale for Localized, Sustained Delivery of Therapeutics

Incorporation of therapeutic agents into external supports can also be considered to improve vein graft and hemodialysis access patency. Localized, sustained release of a therapeutic with mechanisms that align with or are complimentary to the external stent can result in even greater positive outcomes. However, many of the current approaches employing therapeutics to-date have put more focus on the therapeutic itself without as much consideration on the material choice and stent design. The main strategy behind this methodology is to create a therapeutic depot for longer lasting effects and administer higher localized concentrations of drugs to the outer adventitial layer while minimizing damage to the endothelium.[23]

3.2.2. Clinical Trials for Therapeutic-Eluting External Supports

A handful of such approaches have reached clinical trials for improving hemodialysis access patency, but none have been successfully translated to-date. Two of them employed a collagen hydrogel that degrades within weeks, and therefore largely isolated the effects of the therapeutic without the added benefit of longer-term mechanical support. Both aimed to reduce NH by promoting angiogenesis, one by loading the gel with an adenoviral vector containing the VEGF-D gene (Trinam®, Ark Therapeutics Group)[145], and the other by loading the gel with allogenic endothelial cells (Vascugel®, Shire Pharmaceuticals).[146] Trinam® completed a Phase IIb clinical trial but its Phase III trial was terminated for “strategic reasons”,[145] while Vascugel® completed two clinical trials without showing significant patency benefit, terminated a Phase II study, and is no longer a publically-active program at Shire.[146] A third approach loaded a nonbiodegradable ethylene vinyl acetate wrap with paclitaxel (Vascular Wrap®, Angiotech Pharmaceuticals),[147] but the Phase III clinical trial was terminated due to higher infection rates in the paclitaxel-treated group. Currently, a sirolimus-eluting collagen membrane (Coll-R®, Vascular Therapies) is recruiting patients for Phase III clinical trials after completing a first-in-man study demonstrating safety and technical feasibility.[148] Although Coll-R® is biodegradable, it may still bestow infection risks as the immunosuppressant activity of sirolimus has been shown to increase superficial wound infections and other complications following kidney transplantation.[149, 150] Furthermore, the collagen matrix is unlikely to provide much in the way of beneficial mechanical support as it degrades rapidly. For these reasons, alternative therapeutics such as those mentioned in section 1.3 may ultimately be a better option than sirolimus, and other polymeric delivery platforms may be preferable to collagen.

3.2.3. Improving Localization and Release Duration of Therapeutics

To maximize NH reduction and simultaneously minimize the risk of adverse complications, external supports should be engineered that sustain effective yet non-toxic drug concentrations localized within the vein walls without affecting the surrounding tissue. Several techniques have been investigated that aim to achieve these objectives by creating multi-layered systems, microneedles, altering the crosslinking density, copolymerizing, or combinations thereof.[151–161] For example, biodegradable, elastomeric poly(1,8-octanediolcitrate) copolymer membranes eluting vitamin A derivative all-trans retinoic acid (aTRA) exhibited a reduction in NH and restenosis in a rat carotid artery balloon injury model.[161] In another approach, Sanders et al. created a tunable platform to release drugs unidirectionally towards the adventitia. [154] It involved the creation and iteration of a multi-layer system consisting of a non-porous polymer layer ± a porous polymer layer ± a hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel layer loaded with the model drug sunitinib. The groups without the hydrogel had the drug loaded in the non-porous or porous layers instead of the hydrogel, and both PCL and PLGA were examined. The non-porous PCL layer sustained release 4-fold longer than the porous PCL construct (22 days vs. 5 days), while non-porous PLGA delayed release 3-fold (9 days vs. 3 days). It was demonstrated in an external jugular vein porcine model that the non-porous PLGA bilayer evades drug loss, as significantly more drug was detected in the wrapped vein segment versus the adjacent extravascular muscle; at 1 week, 1048 ng g−1 were detected in the vein segment versus none in the extravascular tissue, while at 4 weeks, the amounts were 1742 and 52 ng g−1, respectively. Unidirectional approaches such as this more effectively localize and sustain release of therapeutics, but the effect of a nonporous layer on NH and angiogenesis was not examined.

3.2.3. Comparing Material- and Therapeutic-Based Effects

Material-based effects on graft/access patency should be thoroughly examined and understood before incorporating a therapeutic. While such combinatorial approaches are lacking, some recent approaches have compared material-independent effects to material-drug combined effects.[153, 158, 160] Skalsky et al. loaded 70/30 P(LA/CL) with the immunosuppressant sirolimus and compared graft responses at 3 – 6 weeks in a rabbit jugular vein-to-common carotid artery model.[160] The group observed a significant reduction in intimal, medial, and intimal-medial thickening with both the mesh only and sirolimus-eluting mesh groups. Both groups exhibited a 73% reduction in intimal thickening after 3 weeks compared to the untreated graft. Levels of intimal thickening were the same compared to the untreated graft after 6 weeks for the sirolimus-eluting mesh, while that of mesh alone was 59% reduced at this timepoint. Medial thickness was relatively unchanged for the stent-alone group compared to the unstented graft, while the sirolimus-eluting mesh’s medial thickness was reduced 65% and 20% at 3 and 6 weeks, respectively. Therefore, the sirolimus-eluting mesh reduced the total wall thickness in comparison to mesh alone by 60% and 13% at 3 and 6 weeks. It stands to reason that through more optimization of stent design and a better understanding of its NH-reducing mechanism, a drug better tailored to the external stent’s effects could be identified to maximize long-term patency.

3.3. Experimental Models

In order to optimize external supports, models that are most relevant to the human physiology and most conducive to attaining mechanistic insights of external stents should be employed. No ideal model directly mimetic of NH and human disease conditions currently exists. However, models chosen should match the conduit caliber, hemodynamics, and thrombogenicity as closely as possible to that of the disease state in humans.[162, 163] Larger native vessel diameters should be chosen to best simulate the low shear stress conditions of the anastomoses encountered clinically. This means that large animals such as nonhuman primates, pigs, canines, and sheep are more appropriate selections than small animals for studying an external support’s effects on NH. Nonhuman primates represent the closest approximation to humans in terms of blood compatibility, thrombosis, and endothelialization of devices, but may not always be an option due to high cost and low availability. Other factors that play a role in experimental relevance of external stent assessment are the type of artery and vein employed, length of implantation, and type of anastomosis used (i.e. end-to-side or end-to-end). An end-to-side anastomosis geometry should be employed whenever possible in order to better mimic clinical flow conditions. A detailed assessment of variables to consider when selecting an animal model and differences between them can be found elsewhere.[162, 163]

Ex vivo and in vitro models are often more appropriate in terms of time, cost, and throughput to optimize and screen design parameters. For example, it may be more efficient to assess mechanical properties of external stents in an ex vivo flow-based model. Such ex vivo flow systems have emerged as a useful tool to study human venous tissue responses to treatments while under the duress of physiologically relevant flow and pressure conditions in the absence of blood components.[164, 165] In one study, Longchamp et al. demonstrated that a 4 mm Dacron mesh with 750 μm, diamond-shaped pores (Provena®, B. Braun Medical SA) could reduce distention and NH in an engineered perfusion system that exposed SVGs to physiological pressures (120/80 mmHg at 1 Hz) for 3 or 7 days. The mesh also reduced VSMC apoptosis and subsequent medial fibrosis, while preventing upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9) responsible for depositing the ECM that comprises the neointima. Endothelial function, as measured by gene expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), was also improved with mesh treatments relative to the unstented veins. The meshes exhibited these effects significantly more while exposed to physiological pressures, indicating that the mechanical support provided by the mesh was important in mitigating NH (at least in a blood component-free system). While such findings ultimately need to be proven in a more physiologically-relevant model, this study provides a preliminary example of how ex vivo models can provide unique insights into external stent design parameters.

4. Future Perspectives

4.1. Modular Iteration of External Supports

While several promising studies have been conducted that clearly demonstrate the ability of external stents to reduce NH, there is still no external stent available for patients. More controlled, comparative studies will need to be conducted to isolate variable effects and garner more mechanistic insights on how external stents function. A variety of materials and copolymers should be explored for these purposes. These materials should be biodegradable so as to avoid infection risks from long-term implantation, macroporous to promote neoadventitial growth, and provide some level of mechanical support to reduce tangential wall stresses, either directly or indirectly, through adventitial angiogenesis. Copolymers are useful tools to examine phenomena such as how degradation profiles influence patency,[166] as numerous systems can be devised with tunable degradability by simple alterations in molar composition or molecular weight,[75, 76] and their effects on NH and graft patency can be observed over time. In the same way, copolymer systems can be used to tune mechanical properties and elucidate the level and timeline of support that is most beneficial towards minimizing NH.[167] The extent and timeframe of support-induced angiogenesis most beneficial for reducing NH should also be studied, perhaps by implanting external supports that have angiogenic and/or inflammatory agonists/antagonists incorporated in them.[168]

4.2. Advances in Active Approaches

Further mechanistic insights into passive external design parameter effects on NH reduction can also inform active design approaches. For example, a sustained inflammatory responses from degradation products of an external support could prove to at first be beneficial in reducing NH, but have the opposite effect at later time points due to fibrosis and/or promotion of a synthetic, proliferative VSMC phenotype. In this case, a drug delivery platform can be incorporated that delays release until a later timepoint. Conversely, iterative modulation of active design approaches can inform the passive external support design. For example, a pro-angiogenic drug eluted from an external support may at first have a positive impact, before leading to an increase in NH later on. In this case, a more biocompatible and/or more slowly degrading polymer may be a more appropriate material selection to couple with this drug to mitigate the negative effects that were observed from an overly active angiogenesis.

In a classical scaffold design where the passive external support also serves as the depot for therapeutic agents, it may be difficult to decouple parameter interdependencies in the design such as amount of drug loaded and stent stiffness. The multi-layer polymer wrap or hydrogel systems previously discussed[151–160] may help to isolate these parameters in the design. Another means to accomplish this besides circumscribing polymer or hydrogel layers is to coat the surface with bioactive compounds. For example, heparin coatings can serve a dual purpose of imparting antithrombotic effects while also serving as a drug depot to deliver cationic therapeutics.[169] A common way to render such a surface is to co-employ highly adhesive polymers such as poly(dopamine)[170] or plasma treat the surface.[171] Although not definitively known in the external stenting context, it may also prove beneficial to improve endothelialization of the device, which could be done by coating or modifying the surface with cell-adhesive proteins or peptides such as fibronectin, collagen, gelatin, laminin, or Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD).[169] The topography of the material surface could also be altered via techniques such as electron beam lithography to influence cell behavior and adhesion.[172, 173]

Advanced drug delivery approaches can also be applied to further improve the localization, specificity, and activity of drugs eluted from external supports, thereby reducing NH. For example, PLGA 90/10 microneedles loaded with paclitaxel were recently demonstrated to reduce NH more than free paclitaxel with two orders of magnitude more efficient delivery to the tunica media and adventitia in a rabbit balloon injury model.[156] In another study, Evans et al. demonstrated that pH-responsive nanopolyplexes enable dramatically more efficient intracellular uptake and activity of a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein (MAPKAP) kinase 2 inhibitory peptide (MK2i), significantly reducing NH in human SVGs ex vivo and in an in vivo rabbit vein graft interposition model.[174] While significant regulatory hurdles remain with such approaches, active external stents designs may evolve in the coming years to incorporate more sophisticated and efficient drug delivery systems such as these.

4.3. Improving or Replacing Grafts

Many other approaches to reducing vein graft and hemodialysis access failure are currently being pursued. One area of intensive research has been to improve the performance of the graft itself by either modifying it or replacing it with an alternative material source. Modifications of ePTFE include approaches such as cross-helical yarn coverings to improve flow dynamics, tapering of size to gradually transition from vein to artery, and surrounding the ePTFE with a cuff to reduce regional turbulence, which can be reviewed elsewhere.[29] Alternative graft materials to replace ePTFE or SVGs include other synthetic polymers,[175–179] combinations of synthetic and natural polymers,[180–188] and tissue-engineered vascular grafts (TEVGs) containing either cellularized synthetic/natural polymers[189–196] or decellularized natural materials.[197–199] [198–203] While none of these alternative grafts have achieved significant adoption, Niklason et al. recently demonstrated safety and functionality of a decellularized TEVG (HUMACYL®, Humacyte Inc.) for hemodialysis patients.[199] HUMACYL is a human acellular vessel (HAV) derived from decellularized human tissue. In the 60-person cohort, secondary patency was 89% at one year and Humacyte is now recruiting patients for a Phase III trial. However, despite this promising development, NH will likely remain an issue with these grafts given that primary patency was only 38% for the 60 patients at one year, which compares closer to the 18 month patency rate (33%) than the 6 month patency rate (45%) from Huber et al.[17] Ultimately, a combination of complimentary approaches serve as hope for improving the quality and length of life of CAD, PAD, and ESRD patients.

5. Conclusions

Neointimal hyperplasia is the primary culprit for vein graft failure and hemodialysis access dysfunction. While several promising innovations have been devised, there is still no therapeutic approach currently available to patients to robustly prevent NH. External stents offer a particularly promising therapeutic avenue, as regulatory constraints may be lower for some of these devices, and it also offers the opportunity to combine a synergistic therapeutic payload. In order to translate these approaches to the clinic, a better understanding of NH that is specific to the material selected should be devised. Copolymers and modular iteration of design parameters can ultimately optimize external stent solutions. The effect of material chemistry, biodegradation timeline, mechanical properties, and geometry of the device and pores should all be carefully considered and tested for future devices. In combining biomedical engineering, clinical, and molecular biology insights, better solutions finding success in the clinic can be devised.

Figure 12.

After one month treatment of pig SVGs with the PGA external stent, a notable neoadventitia has formed with endothelial cells lining microvessels and undergoing active angiogenesis. a) Lectin staining (brown) reveals a prominence of adventitial endothelial cells. The black arrow shows blood cells filling microvessels, while some VSMCs surround endothelial cells (white arrow). b) VEGF is also present, indicating active angiogenesis is taking place. Scale bar 50 μm. Reproduced with permission.[92] Copyright 2004, Elsevier.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation (NSF grant AIR-TT 1542996), National Institute of Health (NIH grants ULI TR000445 and 2R01 HL070715), American Heart Association (AHA Pre-doctoral Fellowship 15PRE25610014), and the Faculty Research Assistance Program of Yonsei University College of Medicine for 2000 (6-2016-0031).

Biographies

Timothy Boire is a PhD candidate in Biomedical Engineering at Vanderbilt University. He received his BS in Chemical & Biological Engineering from Tufts University in 2008 and worked for three years in Research & Development at Genzyme Corporation before coming to Vanderbilt. While at Vanderbilt, he has developed a new shape memory polymer library for use in biomedical applications and co-invented an external stent comprised of this material. After leading a team through the NSF I-Corps program and competing in the Rice Business Plan Competition, Tim aims to develop and commercialize technologies such as these that can impact patients.

Daniel Balikov is an MD/PhD student at Vanderbilt University and earning his PhD in Biomedical Engineering. He received his BSE in Bioengineering from the University of Pennsylvania in 2011 and matriculated into the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) that summer. At Vanderbilt, he has studied the structure-functional relationship of material influences on stem cell behavior including synthetic copolymers and monolayer graphene. Dan aims to complete both his PhD and MD training and undergo graduate medical education to practice as a physician scientist by running an independent lab translating engineering solutions to medical problems afflicting the patients he will treat.

Dr. Hak-Joon Sung joined the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Vanderbilt Universing in 2009. His research is primarily focused on identification of the underlying mechanisms by which cells and tissues interact with polymeric materials from nano to organ scales. His group is applying this knowledge to develop the next generation of polymeric biomaterials for regenerative medicine and medical device technologies. He is also a Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Science at Yonsei University College of Medicine in South Korea.

Contributor Information

Timothy C. Boire, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, USA

Daniel A. Balikov, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, USA

Dr. Yunki Lee, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, USA

Dr. Christy M. Guth, Division of Vascular Surgery, Department of Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37235, USA

Dr. Joyce Cheung-Flynn, Division of Vascular Surgery, Department of Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37235, USA

Prof. Hak-Joon Sung, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, USA. Severance Biomedical Science Institute, College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Seoul 120-752, Republic of Korea

References

- 1.Bhasin M, Huang Z, Pradhan-Nabzdyk L, Malek JY, LoGerfo PJ, Contreras M, Guthrie P, Csizmadia E, Andersen N, Kocher O, Ferran C, LoGerfo FW. Plos One. 2012;7:e39123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens CD, Gasper WJ, Rahman AS, Conte MS. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2015;61:203. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taggart DP. Current Opinion in Cardiology. 2014;29:528. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeller T, Rastan A, Macharzina R, Tepe G, Kaspar M, Chavarria J, Beschorner U, Schwarzwälder U, Schwarz T, Noory E. Journal of Endovascular Therapy. 2014;21:359. doi: 10.1583/13-4630MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(suppl 1):S1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourassa M, Fisher L, Campeau L, Gillespie M, McConney M, Lesperance J. Circulation. 1985;72:V71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chesebro JH, Fuster V, Elveback LR, Clements IP, Smith HC, Holmes DRJ, Bardsley WT, Pluth JR, Wallace RB, Puga FJ, Orszulak TA, Piehler JM, Danielson GK, Schaff HV, Frye RL. New England Journal of Medicine. 1984;310:209. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198401263100401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzgibbon GM, Kafka HP, Leach AJ, Keon WJ, Hooper GD, Burton JR. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1996;28:616. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabik JF, III, Lytle BW, Blackstone EH, Houghtaling PL, Cosgrove DM. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2005;79:544. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabik JF. Circulation. 2011;124:273. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conte MS. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2007;45:A74. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harskamp RE, Lopes RD, Baisden CE, de Winter RJ, Alexander JH. Annals of Surgery. 2013;257:824. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288c38d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huijbregts HJT, Bots ML, Wittens CHA, Schrama YC, Moll FL, Blankestijn PJ Cs g on behalf of the. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008;3:714. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02950707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman S, Zadina K, Moritz T, Ovitt T, Sethi G, Copeland JG, Thottapurathu L, Krasnicka B, Ellis N, Anderson RJ, Henderson W. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;44:2149. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung AK, Sarnak MJ, Yan G, Dwyer JT, Heyka RJ, Rocco MV, Teehan BP, Levey AS. Kidney international. 2000;58:353. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray RJ, Horton KM, Dolmatch BL, Rundback JH, Anaise D, Aquino AO, Currier CB, Light JA, Sasaki TM. Radiology. 1995;195:479. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.2.7724770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber TS, Carter JW, Carter RL, Seeger JM. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2003;38:1005. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Jaishi AA, Oliver MJ, Thomas SM, Lok CE, Zhang JC, Garg AX, Kosa SD, Quinn RR, Moist LM. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2014;63:464. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shemesh D, Goldin I, Verstandig A, Berelowitz D, Zaghal I, Olsha O. The journal of vascular access. 2015;16:34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White RA, Hollier LH. Vascular surgery: Basic science and clinical correlations. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newby AC, Zaltsman AB. The Journal of Pathology. 2000;190:300. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<300::AID-PATH596>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitra AK, Gangahar DM, Agrawal DK. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006:84. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee T, Roy-Chaudhury P. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2009;16:329. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi Y, O’Brien JE, Fard A, Mannion JD, Wang D, Zalewski A. Circulation. 1996;94:1655. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.7.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berguer R, Higgins RF, Reddy DJ. Archives of Surgery. 1980;115:332. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1980.01380030078019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharony R, Pintucci G, Saunders PC, Grossi EA, Baumann FG, Galloway AC, Mignatti P. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006;290:H1651. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00530.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox JL, Chiasson DA, Gotlieb AI. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 1991;34:45. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(91)90019-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vijayan V, Smith F, Angelini G, Bulbulia R, Jeremy J. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery: the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2002;24:13. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Terry CM, Shiu Y-TE, Cheung AK. Kidney international. 2008;74:1247. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy-Chaudhury P, Sukhatme VP, Cheung AK. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17:1112. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terry CM, Dember LM. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2013;8:2202. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07360713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thatte HS, Khuri SF. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2001;72:S2245. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGeachie J, Meagher S, Prendergast F. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 1989;59:59. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1989.tb01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chanakira A, Dutta R, Charboneau R, Barke R, Santilli SM, Roy S. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2012;302:H1173. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00411.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Misra S, Fu AA, Misra KD, Shergill UM, Leof EB, Mukhopadhyay D. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2010;21:896. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desai M, Mirzay-Razzaz J, von Delft D, Sarkar S, Hamilton G, Seifalian AM. Vascular Medicine. 2010;15:287. doi: 10.1177/1358863X10366479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motwani JG, Topol EJ. Circulation. 1998;97:916. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.9.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allaire MDE, Clowes MDAW. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1997;63:582. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haruguchi H, Teraoka S. Journal of Artificial Organs. 2003;6:227. doi: 10.1007/s10047-003-0232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dobrin P, Littooy F, Endean E. Surgery. 1989;105:393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muto A, Panitch A, Kim N, Park K, Komalavilas P, Brophy CM, Dardik A. Vascular pharmacology. 2012;56:47. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maiellaro K, Taylor WR. Cardiovascular Research. 2007;75:640. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whittemore AD, Donaldson MC, Polak JF, Mannick JA. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1991;14:340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bizarro P, Coentrão L, Ribeiro C, Neto R, Pestana M. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2011;77:1065. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lok CE, Sontrop JM, Tomlinson G, Rajan D, Cattral M, Oreopoulos G, Harris J, Moist L. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2013;8:810. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00730112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy-Chaudhury P, Kruska L. Seminars in Dialysis. 2015;28:107. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixon BS, Beck GJ, Vazquez MA, Greenberg A, Delmez JA, Allon M, Dember LM, Himmelfarb J, Gassman JJ, Greene T. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:2191. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldman S, Copeland J, Moritz T, Henderson W, Zadina K, Ovitt T, Kern KB, Sethi G, Sharma GV, Khuri S. Circulation. 1994;89:1138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]