Abstract

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental health disorders among adults with adverse childhood experiences (ACE). Several studies have well documented the protective role of social support against depression in other populations. However, the impact of perceived social and emotional support (PSES) on current depression in a large community sample of adults with ACE has not been studied yet. This study tests the hypothesis that PSES is a protective factor against current depression among adults with ACE.

Data from the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) involving adults with at least one ACE were used for the purpose of this study (n = 12.487). PSES had three categories: Always, Usually/Sometimes, and Rarely/Never. Current depression, defined based on the responses to the eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) depression scale, was treated as a binary outcome of interest: Present or absent. Logistic regression models were used for the analysis adjusting for all potential confounders.

When compared to individuals who reported that they rarely/never received social and emotional support, individuals who reported that they always received were 87% less likely to report current depression (AOR: 0.13 [95% CI: 0.08–0.21]); and those who reported that they usually/sometimes received social and emotional support were 69% less likely to report current depression (AOR: 0.31 [95% CI: 0.20–0.46]).

The results of this study highlight the importance of social and emotional support as a protective factor against depression in individuals with ACE. Health care providers should routinely screen for ACE to be able to facilitate the necessary social and emotional support.

Keywords: Perceived social and emotional support, Current depression, Adverse childhood experiences, ACE, BRFSS

Highlights

-

•

This study is the first to show PSES protects against depression among adults with ACE.

-

•

Those who ‘always’ received support were 87% less likely to report depression.

-

•

Those who ‘usually/sometimes’ received support were 69% less likely to report depression.

-

•

Implications of study include emphasis on screening and supportive interventions.

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) are defined as incidents of abuse or household dysfunction during the first 18 years of life. They include verbal, physical, or sexual abuse, as well as household dysfunction such as substance-abusing, mentally ill, or incarcerated family member, and parental divorce/separation or witnessing domestic violence (Felitti et al., 1998). According to the ACE Study, collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente's Health Appraisal Clinic in San Diageo, CA, > 60% of the participants reported at least one adverse childhood experience (CDC, 2014). In recent years, research on adults with ACE has received much attention in public health because of its negative impact on health outcomes. Several studies have well documented the negative impact of ACE on adult health and health risk behaviors (Anda et al., 1999, Chapman et al., 2004, Chapman et al., 2007, Dube et al., 2002, Dube et al., 2003, Felitti et al., 1998, Friestad et al., 2012, Gjelsvik et al., 2014, Kelly-Irving et al., 2013).

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental disorders among adults with ACE. One recent study reported that 4 or more ACE predicted a 23.9% point higher probability of ever-diagnosed depression compared with 0 ACE (Font and Maguire-Jack, 2016). Depression has a significant effect on individuals' health and is associated with enormous economic burden (Moussavi et al., 2007, Wang et al., 2003). By the year 2020, depression will become the second leading cause of death in the world (Murray and Lopez, 1996). As depression remains to be a huge public health concern among adults with ACE, particularly among those who had been sexually abused in childhood (Gladstone et al., 1999), research needs to focus on assessing the role of protective factors (e.g., social support) against depression in such populations. This study focused on social and emotional support because it is one of the most commonly sought safety net for and important resources of coping with adverse events in life.

Social support is a multidimensional construct which includes two types: structural and functional support. Structural social support includes quantity of social relationships (e.g., social integration) whereas functional social support includes quality of social relationships (e.g., emotional support) (Reblin and Uchino, 2008, Schwarzer and Knoll, 2007). Furthermore, functional social support is divided into two types: perceived available support and support actually received. Depending on the wording and context, these two could be closely related or unrelated (Schwarzer and Knoll, 2007). Emotional support is the perceived availability of caring, trusting individuals with whom life experiences can be shared. It involves the provision of love, trust, empathy, and caring, and is the most often thought of support protecting persons from potentially adverse effects of stressful events (Cobb, 1976, Cohen and Wills, 1985, House, 1981). Perceived support was found to be a better predictor of mental health than actual received support (McDowell and Serovich, 2007).

Several studies have well documented the protective role of social support in protecting against depression in a general population and non-ACE populations (e.g., adolescents, individuals with myocardial infarctions, cancer, arthritis, HIV, etc.) (Dingfelder et al., 2010, Fleming et al., 1982, Frasure-Smith et al., 2000, Grav et al., 2012, Kovács et al., 2015, Penninx et al., 1997, Prachakul et al., 2007, Stice et al., 2004, Vyavaharkar et al., 2010, Yang et al., 2010). However, to the best of our knowledge, the influence of perceived social and emotional support on current depression in a large community sample of adults with ACE has not been studied yet. Therefore, the objective of this study is to test our hypothesis that perceived social and emotional support would be a protective factor against current depression among adults with ACE. The study objective attempts to validate the stress-buffering model in an ACE population, which is documented in other non-ACE populations (Aro et al., 1989, Yang et al., 2010). Data from the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) were used to test the proposed hypothesis.

Results from this study have important implications for health care providers to design and implement interventions which may help increase social and emotional support for adults with ACE. Providing such a support system to individuals with ACE may help decrease the severe burden of depression. And, reducing depression can potentially improve individuals' overall quality of life (Jia et al., 2004).

2. Methods

2.1. General study design and population

The BRFSS is a federally funded telephone survey designed and conducted annually by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with state health departments in all 50 states, Washington, DC; Puerto Rico; the US Virgin Islands; and Guam. The survey collects data on health conditions, preventive health practices and risk behaviors of the adults' selected. All BRFSS questionnaires, data and reports are available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Data for this study were obtained from 5 states (Hawaii, Nevada, Ohio, Vermont, and Wisconsin) that administered the ‘Adverse Childhood Experience’ and the ‘Anxiety and Depression’ optional modules in the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS). According to the Council of American Survey Research Organization (CASRO) guidelines, the response rates for these states ranged from 49.1% to 60.5%.

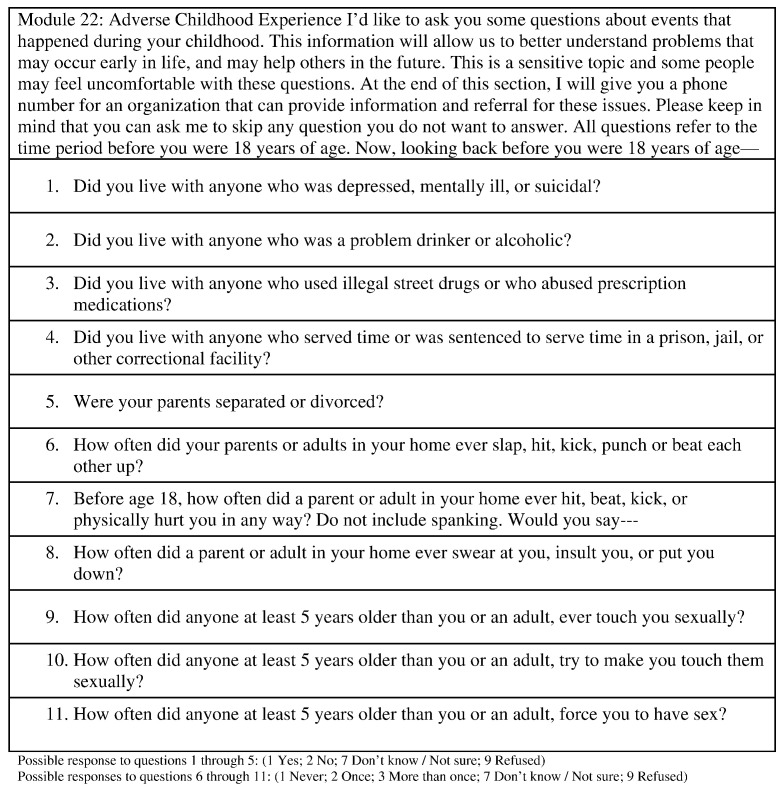

2.2. Adverse childhood experiences (ace): population of interest

The adverse childhood experiences were assessed based on a total of 11 questions in the BRFSS ACE module (Fig. 1.). These 11 questions were grouped into eight categories: i) physical abuse, ii) verbal abuse, iii) sexual abuse, iv) mental illness in a household member, v) substance abuse in a household member, vi) divorce of a household member, vii) incarceration of a household member, and viii) witnessed abuse of a household member. We considered categories i) – iii) as direct ACE and iv) – viii) as indirect ACE. Individuals who experienced at least one of the eight adverse childhood events were considered as the population of interest in this study (n = 13.992).

Fig. 1.

BRFSS Module 22: Adverse Childhood Experience.

Possible response to questions 1 through 5: (1 Yes; 2 No; 7 Don't know/Not sure; 9 Refused).

Possible responses to questions 6 through 11: (1 Never; 2 Once; 3 More than once; 7 Don't know/Not sure; 9 Refused).

2.3. Perceived social and emotional support (PSES): primary exposure of interest

Perceived social and emotional support (PSES) was assessed by asking the question: “How often do you get the social and emotional support you need?” Possible responses were: Always, Usually, Sometimes, Rarely, or Never. In our analysis, we divided these responses into three categories: Always, Usually/Sometimes, and Rarely/Never. Similar classification has been used in other studies (Edwards et al., 2016). Since the actual support received was not measured objectively in this study, responses from the study participants to this question on social and emotional support are considered as perceived rather than received.

2.4. Current depression: primary outcome of interest

Current depression is defined based on the responses to the eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) depression scale. The scores for each item, which ranges from 0 to 3, are summed to produce a total score between 0 and 24 points. Current depression was defined as a PHQ-8 score ≥ 10 (Kroenke et al., 2009). The PHQ-8 consists of eight of the nine DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

2.5. Covariates of interest

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment, general health, exercise, and body mass index were considered as covariates of interest in this study.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All analysis is restricted to adults with at least one adverse childhood experience. Sampling weights provided in the 2010 BRFSS public-use data that adjust for unequal selection probabilities, survey non-response, and oversampling were used to account for the complex sampling design and to obtain population-based estimates which reflect US non-institutionalized individuals with at least one ACE. We first calculated the weighted prevalence estimate and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for current depression and PSES among all individuals with at least one ACE (n = 13.992). In order to describe the characteristics of the study population, weighted prevalence estimates, and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed based on the sample of individuals with complete data on all variables considered in this study (n = 12.487). Association between PSES and current depression was examined using logistic regression models. Since the perception of social support has different consequences for the psychological well-being for men and women (Flaherty and Richman, 1989), to examine gender-specific association between PSES and current depression, we conducted stratified analyses by gender (males, females).

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) using SAS survey procedures (PROC SURVEYFREQ, PROC SURVEYMEANS, PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC) to account for the complex sampling design.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Among individuals with at least one ACE, 13.0% (95% CI: 11.6%–14.5%) reported current depression; 43.2% (95% CI: 41.2%–45.1%) reported that they always received social and emotional support, followed by usually/sometimes [48.2% (95% CI: 46.2%–50.1%)], and rarely/never [7.5% (95% CI: 6.6%–8.5%)]. Table 1 describes the sample characteristics of individuals with complete data. The average age was about 45 years, 49.1% were male, 81.1% were White Non-Hispanic, 60.6% were married, 38.9% had less than high-school education, 61.6% were employed, 84% reported either excellent, very good, or good general health, 29.2% were obese, and 24.4% reported no physical activity. The prevalence of current depression was the lowest among individuals who reported that they always received social and emotional support [6.4% (95% CI: 4.9%–7.9%)], followed by a prevalence of 14.5% (95% CI: 12.3%–16.7%) among those who reported that they usually/sometimes received social and emotional support, and a prevalence of 44.4% (95% CI: 40.0%–51.9%) among those who reported that they rarely/never received social and emotional support.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of adults with adverse childhood experiences, according to perceived social and emotional support.

| Perceived social and emotional support |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 12.487) |

Rarely/Never (n = 1000) |

Usually/Sometimes (n = 5977) |

Always (n = 5510) |

|||||

| Unweighted “n” | Mean or Proportion (95% CI) | Mean or Proportion (95% CI) | Mean or Proportion (95% CI) | Mean or Proportion (95% CI) | ||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 5005 | 49.1(47.0, 51.2) | 62.9 | (56.5, 69.3) | 46.7 | (43.6, 49.8) | 49.6 | (46.5, 52.8) |

| Female | 7482 | 50.9(48.8, 53.0) | 37.1 | (30.7, 43.5) | 53.3 | (50.2, 56.4) | 50.4 | (47.2, 53.5) |

| Education | ||||||||

| < High school | 4420 | 38.9(36.8, 40.9) | 56.9 | (49.8, 64.0) | 36.8 | (33.8, 39.8) | 38.3 | (35.3, 41.3) |

| High school | 3648 | 29.3(27.4, 31.1) | 29.1 | (22.9, 35.3) | 29.1 | (26.5, 31.7) | 29.5 | (26.6, 32.4) |

| > High school | 4419 | 31.8(29.9, 33.8) | 14.0 | (9.1, 18.9) | 34.1 | (31.2, 37.0) | 32.2 | (29.2, 35.2) |

| Marriage | ||||||||

| Married | 6800 | 60.6(58.6, 62.7) | 47.3 | (39.9, 54.6) | 58.6 | (55.6, 61.5) | 65.0 | (62.0, 68.0) |

| Previously Marrieda | 3444 | 16.1(14.8, 17.3) | 28.8 | (23.1, 34.4) | 15.9 | (14.1, 17.8) | 14.2 | (12.3, 16.0) |

| Unmarried | 2243 | 23.3(21.4, 25.2) | 24.0 | (17.1, 30.9) | 25.5 | (22.7, 28.3) | 20.8 | (18.1, 23.6) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White Non-Hispanic | 9325 | 81.1(79.6, 82.6) | 76.1 | (70.9, 81.3) | 83.2 | (81.1, 85.3) | 79.6 | (77.2, 82.0) |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 511 | 6.1(5.2, 7.1) | 6.4 | (3.8, 9.0) | 5.2 | (3.9, 6.5) | 7.1 | (5.5, 8.7) |

| Hispanic | 516 | 4.6(3.7, 5.4) | 4.1 | (1.9, 6.3) | 4.5 | (3.3, 5.8) | 4.7 | (3.4, 6.0) |

| Other Non-Hispanicb | 2135 | 8.2(7.2, 9.1) | 13.5 | (9.4, 17.5) | 7.0 | (5.8, 8.2) | 8.6 | (7.0, 10.1) |

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Employed | 7060 | 61.6(59.6, 63.6) | 41.8 | (34.5, 49) | 64.2 | (61.4, 67.1) | 61.7 | (58.8, 64.7) |

| Out of work | 920 | 9.9(8.5, 11.3) | 13.6 | (8.5, 18.7) | 11.9 | (9.4, 14.3) | 7.2 | (5.6, 8.8) |

| Retired | 2759 | 12.7(11.6, 13.7) | 18.1 | (13.7, 22.6) | 9.3 | (8.1, 10.6) | 15.5 | (13.7, 17.2) |

| Unable to work | 822 | 5.7(4.8, 6.6) | 17.9 | (11.2, 24.6) | 4.9 | (3.8, 6.0) | 4.7 | (3.5, 5.9) |

| Homemaker/Student | 926 | 10.1(8.8, 11.4) | 8.6 | (5.1, 12.1) | 9.6 | (8.0, 11.3) | 10.9 | (8.7, 13.0) |

| Outcome of interest | ||||||||

| Current depression | ||||||||

| Depression score < 10 | 11,087 | 87.0(85.5, 88.4) | 55.6 | (48.1, 63.0) | 85.5 | (83.3, 87.7) | 93.6 | (92.1, 95.1) |

| Depression score ≥ 10 | 1400 | 13.0(11.6, 14.5) | 44.4 | (37.0, 51.9) | 14.5 | (12.3, 16.7) | 6.4 | (4.9, 7.9) |

| Other variables of Interest | ||||||||

| General health | ||||||||

| Excellent/Very good | 10,301 | 84.0(82.6, 85.4) | 63.0 | (56.0, 70.0) | 84.0 | (82.0, 86.0) | 87.4 | (85.6, 89.2) |

| Fair/Poor | 2186 | 16.0(14.6, 17.4) | 37.0 | (30.0, 44.0) | 16.0 | (14.0, 18.0) | 12.6 | (10.8, 14.4) |

| Exercise | ||||||||

| No | 2704 | 24.4(22.6, 26.2) | 45.8 | (38.3, 53.2) | 23.4 | (20.9, 25.8) | 22.2 | (19.6, 24.8) |

| Yes | 9783 | 75.6(73.8, 77.4) | 54.2 | (46.8, 61.7) | 76.6 | (74.2, 79.1) | 77.8 | (75.2, 80.4) |

| BMI | ||||||||

| Not overweight or obese | 4557 | 35.5(33.5, 37.5) | 26.0 | (20.5, 31.5) | 35.7 | (32.8, 38.7) | 36.6 | (33.6, 39.7) |

| Overweight | 4366 | 35.2(33.3, 37.3) | 39.9 | (32.3, 47.6) | 35.4 | (32.5, 38.3) | 34.4 | (31.4, 37.3) |

| Obese | 3564 | 29.3(27.4, 31.2) | 34.0 | (27.3, 40.7) | 28.9 | (26.2, 31.6) | 29.0 | (26.1, 31.8) |

Previously Married includes those divorced, widowed, or separated.

Other Non-Hispanic includes Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaskan Native, multiracial and other race, non-Hispanic.

3.2. Model based prevalence odds ratios for current depression

Table 2 presents the model based prevalence odds ratios both unadjusted (UOR) and adjusted (AOR), and the corresponding 95% CI, for current depression among individuals with at least one ACE who reported that they always or usually/sometimes received social and emotional support when compared to those who reported that they rarely/never received (reference group). After adjusting for all socio-demographic variables, PSES was negatively associated with current depression. When compared to individuals who reported that they rarely/never received social and emotional support, individuals who reported that they always received were 87% less likely to report current depression (AOR: 0.13 [95% CI: 0.08–0.21]); and those who reported that they usually/sometimes received social and emotional support were 69% less likely to report current depression (AOR: 0.31 [95% CI: 0.20–0.46]). Gender did not significantly modify the association between PSES and current depression.

Table 2.

Association between perceived social and emotional support and prevalence of current depression among all and by gender.

| Current depression among all |

Current depression among males |

Current depression among females |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UOR | AOR | UOR | AOR* | UOR | AOR* | |

| Perceived social and emotional support | ||||||

| Rarely/Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Usually/Sometimes | 0.21 (CI: 0.15–0.30) | 0.31 (CI: 0.20–0.47) | 0.18 (CI: 0.10–0.32) | 0.29 (CI: 0.16–0.54) | 0.21 (CI: 0.14–0.31) | 0.32 (CI: 0.20–0.51) |

| Always | 0.09 (CI: 0.06–0.13) | 0.13 (CI: 0.08–0.21) | 0.08 (CI: 0.04–0.14) | 0.15 (CI: 0.07–0.33) | 0.08 (CI: 0.05–0.13) | 0.13 (CI: 0.07–0.22) |

UOR: Unadjusted Odds Ratio.

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio. Adjusted for type of ACE exposure, Age, Gender, Ethnicity, Education, Marital Status, Employment, General Health, BMI, and Exercise.

AOR*: Adjusted Odds Ratio. Adjusted for type of ACE exposure, Age, Ethnicity, Education, Marital Status, Employment, General Health, BMI, and Exercise.

4. Discussion

4.1. Study overview

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to use nationally representative data that documented the association between PSES and current depression among adults with ACE. The current study found a significant negative association between PSES and current depression after controlling for all potential confounders.

4.2. Main findings

Among adults with ACE, PSES significantly reduced the likelihood to report current depression by at least 53% and as high as 92%. This finding is consistent with the stress-buffering model in which, support when measured as the perceived availability of interpersonal resources that are responsive to the needs elicited by stressful events in life attenuates the impact of stressful life events on psychological distress (Cohen and Wills, 1985, Cohen, 2004, Windle, 1992). The direction of association between PSES and current depression found in this study is consistent with other studies conducted in other populations (Dingfelder et al., 2010, Fleming et al., 1982, Frasure-Smith et al., 2000, Grav et al., 2012, Kovács et al., 2015, Penninx et al., 1997, Prachakul et al., 2007, Stice et al., 2004, Vyavaharkar et al., 2010, Yang et al., 2010). A recent study among American Indian older adults with ACE, found that social support is negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Roh et al., 2015). Our findings validate the protective role of social and emotional support against psychological distress among adults with ACE in the US general population.

In the current study, 7.5% of adults who reported at least one ACE reported that they rarely/never received social and emotional support. Considering the findings of this study which suggest that social and emotional support buffers against the harmful impact of ACE on current depression, it is important to identify the characteristics of such individuals so that they can benefit from strategies designed to target and facilitate the necessary social and emotional support. This study found that those who reported that they rarely/never received social and emotional support were significantly older (50.2 years of age), predominantly male (62.9%), had less than high school education (56.9%), were single (52.7%), currently not employed (59.2%), reported fair/poor general health (37.0%), did not exercise (45.8%), when compared to those who reported that they always or usually/sometimes received social and emotional support (Table 1). The characteristics of these individuals in the study are comparable to the characteristics of individuals in the general US population who reported they rarely/never received social and emotional support (Strine et al., 2008).

4.3. Association between PSES and current depression within each category of ACE and ACE score

In order to examine if the association between PSES and current depression would be altered within each category of ACE, or due to a dose-response as defined by the number of ACE (ACE score), we conducted stratified analyses by ACE category [8 categories: i) physical abuse, ii) verbal abuse, iii) sexual abuse, iv) mental illness in a household member, v) substance abuse in a household member, vi) divorce of a household member, vii) incarceration of a household member, and viii) witnessed abuse of a household member.] and ACE score (1, 2, 3, or ≥ 4). Of the eight categories of ACE, i) - iii) were considered as direct abuse and iv)–viii) were considered as indirect abuse. Each stratum specific ACE category analysis was adjusted for all potential confounders including the other 7 ACE categories.

For each category of ACE and by the ACE score, Table 3, Table 4 present the model based prevalence odds ratios both unadjusted (UOR) and adjusted (AOR), and the corresponding 95% CI, for current depression among individuals who reported PSES. The association between PSES and current depression was not altered by the type of ACE category or the ACE score. This could be because PSES is prospective and pertains to anticipating help in time of need (Schwarzer and Knoll, 2007), rather than support actually received. Future studies should assess the protective role of actual support received against current depression and if it is modified by the type of ACE or ACE score.

Table 3.

Association between perceived social and emotional support and prevalence of current depression based on the type of adverse childhood experience.

| Emotional support |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rarely/Never | Usually/Sometimes | Always | |

| Direct abuse | |||

| Current depression among sexually abused (n = 2618) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.18(0.10–0.34) | 0.06(0.03–0.13) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.25(0.12–0.53) | 0.07(0.03–0.18) |

| Current depression among physically abused (n = 3548) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.22(0.13–0.38) | 0.11(0.06–0.02) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.36(0.18–0.70) | 0.15(0.07–0.33) |

| Current depression among verbally abused (n = 7112) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.18(0.12–0.28) | 0.08(0.05–0.13) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.31(0.18–0.52) | 0.14(0.08–0.26) |

| Indirect abuse | |||

| Current depression among those with mental illness in a household member (n = 3304) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.14(0.08–0.27) | 0.06(0.03–0.12) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.24(0.12–0.47) | 0.13(0.06–0.27) |

| Current Depression among those with substance abuse in a household member (n = 5644) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.21(0.13–0.35) | 0.09(0.05–0.15) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.34(0.18–0.64) | 0.13(0.06–0.28) |

| Current depression among those with parents divorced/separated (n = 4296) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.21(0.11–0.38) | 0.11(0.06–0.21) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.29(0.16–0.53) | 0.17(0.08–0.35) |

| Current depression among those who witnessed abuse (n = 3374) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.23(0.13–0.39) | 0.10(0.06–0.18) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.20(0.10–0.37) | 0.09(0.04–0.18) |

| Current depression among those with incarceration of a household member (n = 946) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.25(0.10–0.62) | 0.13(0.05–0.37) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.22(0.07–0.73) | 0.07(0.02–0.25) |

UOR: Unadjusted Odds Ratio.

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio. Adjusted for the remaining types of ACE exposure, Age, Gender, Ethnicity, Education,

Marital Status, Employment, General Health, BMI, and Exercise.

Table 4.

Association between perceived social and emotional support and prevalence of current depression based on ACE score.

| Emotional Support |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rarely/Never | Usually/Sometimes | Always | |

| Current depression among those with ACE total score = 1 (n = 4604) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.19(0.09–0.42) | 0.09(0.04–0.20) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.25(0.10–0.62) | 0.10(0.04–0.26) |

| Current depression among those with ACE total score = 2 (n = 2723) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.32(0.14–0.70) | 0.10(0.04–0.23) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.47(0.21–1.03) | 0.18(0.07–0.43) |

| Current depression among those with ACE total score = 3 (n = 1732) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.34(0.15–0.75) | 0.17(0.06–0.53) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.33(0.11–0.95) | 0.14(0.04–0.53) |

| Current depression among those with ACE total score ≥ 4 (n = 3428) | |||

| UOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.16(0.10–0.28) | 0.09(0.05–0.15) |

| AOR (%95%CI) | Reference | 0.21(0.12–0.36) | 0.10(0.05–0.21) |

UOR: Unadjusted Odds Ratio.

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio. Adjusted for Age, Gender, Ethnicity, Education, Marital Status, Employment, General Health, BMI, and Exercise.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge this study has several limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the BRFSS data, a conclusion about the causal relationship between PSES and current depression is precluded. BRFSS data are based on self-report and therefore may be subject to recall-bias. However, the validity and reliability of questions on ACE is well established (Dube et al., 2004, Hardt and Rutter, 2004). The question used to assess PSES in the BRFSS was not specific to adults with ACE. Also, it is possible that individuals with current depression may underreport PSES compared to those without current depression. Thus, it is likely that the reported magnitude of the association between PSES and current depression is conservative. It is possible that depression may result in lower PSES, a critical aspect for future research to study the opposite of what is theorized in the current study. Finally, since not all states administered the ACE module and because BRFSS is limited to non-institutionalized individuals and household with a telephone, the results of this study may not have included individuals who are homeless, in prisons, or in shelters, etc., and therefore findings from this study may not be generalizable.

4.5. Conclusions

Using a nationally representative sample, this study is the first to show that self-rated PSES is a protective factor against current depression among adults with ACE. The results of this study highlight the importance of social and emotional support in buffering against current depression and confirm the validity of the stress-buffering model documented in several other studies using different populations (Aro et al., 1989, Yang et al., 2010). Also, findings from the current study highlight the importance for health care providers to routinely screen for ACE so that they can facilitate the necessary social and emotional support as a buffer against psychological distress. Future studies should consider interventions aiming to promote social and emotional support and its effect on decreasing the burden of psychological distress. Reducing psychological distress may improve the overall quality of life.

Funding source

No external funding was secured for this study.

Financial disclosure

Authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Author's contribution

Dr. Cheruvu conceptualized and designed the study, designed the analytic plan, conducted the analyses, drafted, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ms. Brinker designed the analytic plan, conducted the analyses, drafted, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Emily Dames, Joan Hall, Victoria Holbrook, Jordan Williams, and Dominic Zimmerman, for their valuable contributions to this project and discussions for the early versions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . fourth ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Anda R.F., Croft J.B., Felitti V.J. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282(17):1652–1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro H., Hänninen V., Paronen O. Social support, life events and psychosomatic symptoms among 14–16-year-old adolescents. Soc. Sci. Med. 1989;29(9):1051–1056. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/ACEtudy/prevalence.html (Last updated: May 13, 2014. Accessed January 27, 2016)

- Chapman D.P., Whitfield C.L., Felitti V.J., Dube S.R., Edwards V.J., Anda R.F. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J. Affect. Disord. 2004;82(2):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman D.P., Dube S.R., Anda R.F. Adverse Childhood Events as Risk Factors for Negative Health Outcomes. Psychiatr. Ann. 2007;37(5) [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976;38(5):300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am. Psychol. 2004;59(8):676. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Wills T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985;98(2):310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingfelder H.E., Jaffee S.R., Mandell D.S. The impact of social support on depressive symptoms among adolescents in the child welfare system: a propensity score analysis. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2010;32(10):1255–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Anda R.F., Felitti V.J., Edwards V.J., Croft J.B. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict. Behav. 2002;27(5):713–725. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Felitti V.J., Dong M., Giles W.H., Anda R.F. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Prev. Med. 2003;37(3):268–277. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Williamson D.F., Thompson T., Felitti V.J., Anda R.F. Assessing the reliability of retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences among adult HMO members attending a primary care clinic. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(7):729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards V.J., Anderson L.A., Thompson W.W., Deokar A.J. Mental health differences between men and women caregivers, BRFSS 2009. J. Women Aging. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2016.1223916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty J., Richman J. Gender differences in the perception and utilization of social support: theoretical perspectives and an empirical test. Soc. Sci. Med. 1989;28(12):1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R., Baum A., Gisriel M.M., Gatchel R.J. Mediating influences of social support on stress at Three Mile Island. J. Hum. Stress. 1982;8(3):14–23. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1982.9936110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font S.A., Maguire-Jack K. Pathways from childhood abuse and other adversities to adult health risks: the role of adult socioeconomic conditions. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;51:390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N., Lespérance F., Gravel G. Social support, depression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101(16):1919–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friestad C., Åse-Bente R., Kjelsberg E. Adverse childhood experiences among women prisoners: relationships to suicide attempts and drug abuse. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0020764012461235. (p. 0020764012461235) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjelsvik A., Dumont D.M., Nunn A., Rosen D.L. Adverse childhood events: incarceration of household members and health-related quality of life in adulthood. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(3):1169–1182. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone G., Parker G., Wilhelm K., Mitchell P., Austin M.P. Characteristics of depressed patients who report childhood sexual abuse. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1999 doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grav S., Hellzèn O., Romild U., Stordal E. Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012;21(1–2):111–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J., Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J.S. 1981. Work Stress and Social Support. [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Uphold C.R., Wu S., Reid K., Findley K., Duncan P.W. Health-related quality of life among men with HIV infection: effects of social support, coping, and depression. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2004;18(10):594–603. doi: 10.1089/apc.2004.18.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Irving M., Mabile L., Grosclaude P., Lang T., Delpierre C. The embodiment of adverse childhood experiences and cancer development: potential biological mechanisms and pathways across the life course. Int. J. Public Health. 2013;58(1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács P., Pánczél G., Balatoni T. Social support decreases depressogenic effect of low-dose interferon alpha treatment in melanoma patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015;78(6):579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Strine T.W., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.W., Berry J.T., Mokdad A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009;114(173):163. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell T.L., Serovich J.M. The effect of perceived and actual social support on the mental health of HIV-positive persons. AIDS Care. 2007;19(10):1223–1229. doi: 10.1080/09540120701402830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi S., Chatterji S., Verdes E., Tandon A., Patel V., Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J.L., Lopez A.D. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1996. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Penninx B.W., Van Tilburg T., Deeg D.J., Kriegsman D.M., Boeke A.J.P., Van Eijk J.T. Direct and buffer effects of social support and personal coping resources in individuals with arthritis. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997;44(3):393–402. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prachakul W., Grant J.S., Keltner N.L. Relationships among functional social support, HIV-related stigma, social problem solving, and depressive symptoms in people living with HIV: a pilot study. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18(6):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reblin M., Uchino B.N. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2008;21(2):201. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f3ad89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh S., Burnette C.E., Lee K.H., Lee Y.S., Easton S.D., Lawler M.J. Risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms among American Indian older adults: adverse childhood experiences and social support. Aging Ment. Health. 2015 doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.938603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R., Knoll N. Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: a theoretical and empirical overview. Int. J. Psychol. 2007;42(4):243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E., Ragan J., Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004;113(1):155. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strine T.W., Chapman D.P., Balluz L., Mokdad A.H. Health-related quality of life and health behaviors by social and emotional support. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008;43(2):151–159. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0277-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyavaharkar M., Moneyham L., Corwin S., Saunders R., Annang L., Tavakoli A. Relationships between stigma, social support, and depression in HIV-infected African American women living in the rural Southeastern United States. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(2):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.S., Simon G., Kessler R.C. The economic burden of depression and the cost-effectiveness of treatment. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2003;12(1):22–33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. A longitudinal study of stress buffering for adolescent problem behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 1992;28(3):522. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Yao S., Zhu X. The impact of stress on depressive symptoms is moderated by social support in Chinese adolescents with subthreshold depression: a multi-wave longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;127(1):113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.