Abstract

The primary splenic lymphoma is extremely uncommon, can present with grave complications like hypersplenism and splenic rupture. In view of vague clinical presentation, it is difficult to arrive at the diagnosis. In such circumstances, histopathological diagnosis is very important. A precise diagnosis can only be made on histopathology and confirmed on immunohistochemistry.Emergency splenectomy is preferred as an effective therapeutic and diagnostic tool in cases with giant splenomegaly. Core biopsy is usually not advised due to a high risk of post-core biopsy complications in view of its high vascularity and fragility. Aim behind highlighting the topic is to specify that core biopsy/ fine needle aspiration cytology can be used as an effective diagnostic tool to arrive at correct diagnosis to prevent untoward complications related to disease and treatment. Anticoagulation therapy is vital after splenectomy to avoid portal splenic vein thrombosis.

Keywords: Splenic lymphoma, Biopsy, Immunohistochemistry

Core tip: Primary splenic lymphoma is a rare entity, has vague clinical presentation and can present with grave complications like hypersplenism and splenic rupture. In such circumstances, core biopsy/fine needle aspiration cytology can hit the correct pathological diagnosis. Emergency splenectomy is an effective therapeutic and diagnostic tool in cases with massive splenomegaly with features of hypersplenism.

INTRODUCTION

Primary splenic lymphoma (PSL) is very unusual entities if strict diagnostic criteria are applied[1]. As per previous studies the final diagnosis of PSL should be made only when the disease is limited to spleen or involving hilar lymph nodes without any recurrence after splenectomy[1-4]. In patients with PSL, therapeutic splenectomy is to be done. However, presently ultrasound guided core biopsy is a safe and efficient diagnostic investigation, can be used routinely. Therapeutic splenectomy is to be followed by anticoagulation therapy and chemotherapy[5].

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Incidence

PSL is a rare neoplasm of the spleen, probably comprising less than 2% of all the lymphomas[6,7] and 1% of all the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas[2,8-10].

Types

There are two main types: (1) splenic lymphoma with circulating villous lymphocytes[6]; and (2) marginal zone splenic lymphoma originating from a peculiar splenic B-cell structure separated by the mantle zone.

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS

Nonspecific symptoms

Clinical presentations of nonspecific symptoms are weight loss, weakness, fever, and lower upper quadrant pain or discomfort due to enlarged spleen.

Specific symptoms

Clinical presentations of specific symptoms are mainly due to invasion of lymphoma cells in to adjacent organs stomach, pancreas, diaphragm, colon, or mesentery[11-16].

Hematological parameters

Cytopaenia can also be a presenting feature[7]. The complete blood count and peripheral smear (PS) findings are mostly unremarkable[17]. Elevation of ESR may be noted[7].

Other presentations

PSL presenting as splenic abscess although uncommon, is associated with high morbidity and death rates due to delayed diagnosis and management[18]. Due to vague presentation, the clinical diagnosis is difficult[19]. Splenic lymphomas usually present as space occupying solid lesions and when present as splenic abscesses are usually encountered in patients with underlying disorders, including infections, emboli, trauma, recent surgery, malignant hematologic conditions and immunosuppression[20].

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

The nonspecific clinical presentation of PSL creates the real diagnostic dilemma.

Reference criteria for diagnosis/staging PSL

Dasgupta et al[1] reported that Lymphoma restricted to the spleen and hilar lymph nodes. Further confirmed following a 6-mo relapse-free period following splenectomy. Skarin et al[21] reported that lymphoma with splenic involvement in which splenomegaly is the dominant feature. Dachman et al[14] reported that splenic lesions with hypodensity on contrast enhanced Computed tomography scans or lesions with hypoechogenecity on ultrasound (USG) studies. Ahmann et al[11] reported that stage I refers to disease confined to the spleen; Stage II refers to splenic involvement along with hilar lymph nodes; Stage III refers to extra-splenic nodal or hepatic involvement.

Peripheral blood smear evaluation

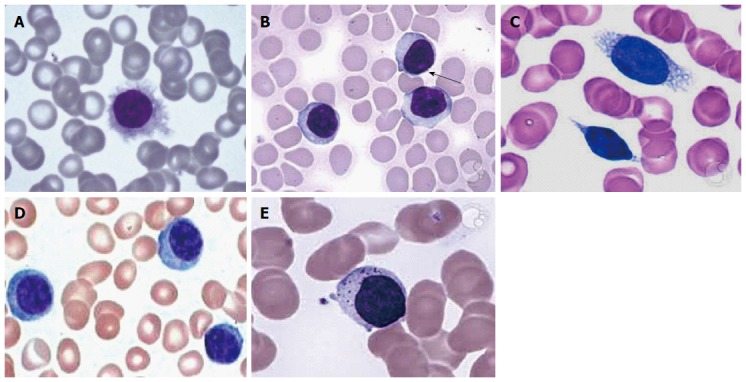

Most of the patients we can reveal neoplastic lymphoid cells on peripheral blood smear, i.e., hairy cells, prolymphocytes, villous lymphocytes, basophilic villous lymphocytes, etc., which may raise the suspicion of neoplastic lymphoid disease in the mind of pathologist (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Peripheral blood smear. A: Hairy cells; B: Prolymphocytes; C: Villous lymphocytes; D: Plasmacytoid lymphocytes; E: Granular lymphocytes.

Biopsy

Core biopsy/fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) are traditionally not recommended in view of high fragility of splenic tissue leading to hemorrhagic complications. However, currently it can be used as a routine diagnostic test[22].

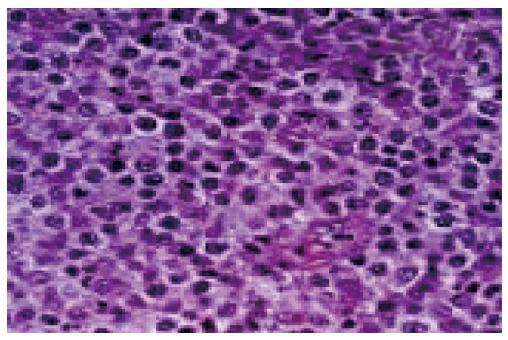

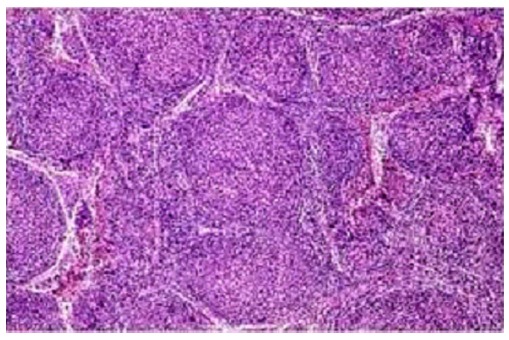

In diffuse large B cell lymphoma: Microscopy predominantly shows monotonous population of large neoplastic lymphoid cells with large areas of necrosis[5].The individual cells essentially demonstrated a large atypical nucleus, irregular nuclear borders with vesicular chromatin and prominent nuclei. Histopathological examination reported as Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma of diffuse large B cell phenotype[5] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma showing monotonous population of large neoplastic lymphoid cells.

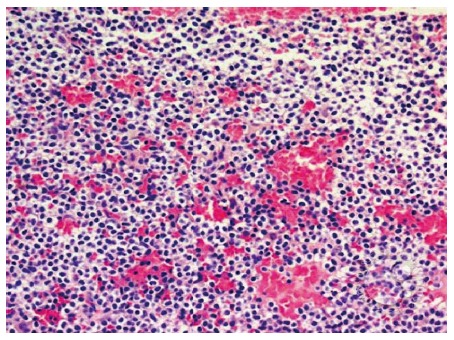

Hairy cell leukemia: Shows the small to medium sized lymphocytic infiltrate more clearly. Round to kidney-shaped with abundant clear cytoplasm are usually revealed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Small to medium sized lymphocytic infiltrate.

Marginal zone splenic lymphoma: Splenic white pulp reactive germinal centres show small neoplastic lymphoid cells almost replacing the mantle zone with occasional large blast like malignant lymphoid cells. Other points we have to reveal are epithelial histocytes, sinus invasion, and plasmacytic differentiation of proliferating cells[5] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Splenic white pulp are replaced by small neoplastic lymphocytes.

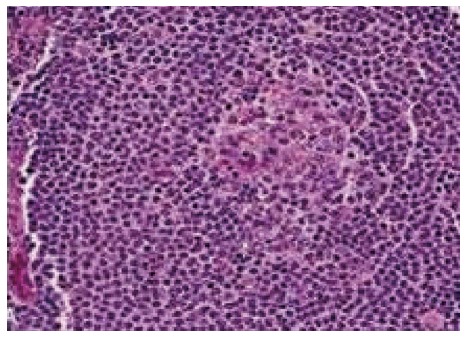

PSL (follicular type): It is neoplastic proliferation of follicle center B-cells, i.e., centrocytes and centroblasts exhibiting follicular pattern (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Neoplastic lymphoid cells arranged predominantly in follicular pattern.

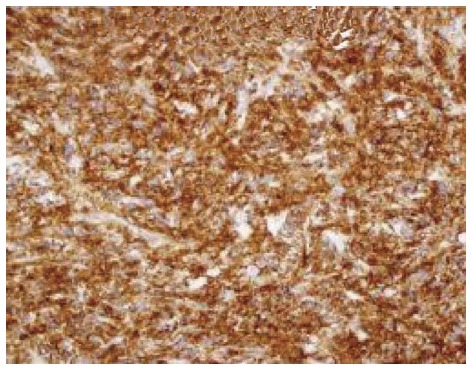

Immunohistochemistry

Histopathology report is to be confirmed by IHC. The tumor cells are immunopositive for B cell markers, e.g., CD 20 and immunonegative for T cell markers (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

CD20 immunopositivity in neoplastic lymphoid B cells.

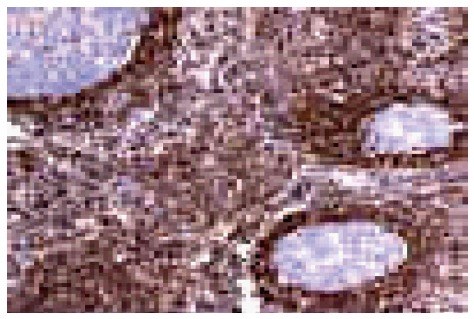

B cell lymphoma: B cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) immunoreactivity is useful to differentiate malignant lymphoma (BCL-2 positive) from reactive (BCL-2 negative) B cells in the marginal zone (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

B cell lymphoma-2 expression in follicular lymphoma.

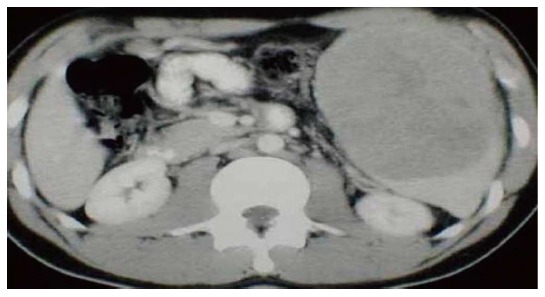

Diagnostic imaging

US imaging of the abdomen and whole-body computed tomography (Figure 8) scan are to be done in each and every case with splenomegaly. The B mode USG determines the actual size of spleen and computed tomography confirms the involvement of hilar lymph nodes[23,24].

Figure 8.

Computed tomography showing massive splenomegaly on ultrasonography.

DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC SPLENECTOMY

The previous workers suggested splenectomy as an effective diagnostic and therapeutic tool[25,26]. It has morbidity and mortality rates accounting for approximately 12% and less than 1%, respectively[27]; Now a days, laparoscopic splenectomy can be used as a safe and efficient method, reducing both the mortality and morbidity significantly[28]. In this the distortion of the samples should be strictly avoided.

Needle core biopsy is more efficient and safe and can be used in high risk patients also. Previous studies[29,30] concluded that splenic needle biopsy has low complication rates with high diagnostic utility. Recently, laparoscopic splenectomy has often been used for splenic masses because of fewer complications and since it is rather appropriate for moderate splenomegaly[30,31].

Echo-guided splenic biopsy and FNAC are effective in peripherally located lesions[32].

Splenic DLBCLs are clinically aggressive neoplasms. So, line of treatment of such SLs should be same as DLBCLS[33]. Splenic form of the micronodular T-cell/histiocyte-rich DLBCL subtype presents with micronodules in the spleen with involvement of bone marrow or other extranodal sites[34,35].

Gastrosplenic fistula is associated with benign peptic ulcer disease, gastric Crohn’s disease, gastric adenocarcinoma, and primary gastric and splenic lymphomas. There occurs hemorrhage due to erosion by primary splenic lesion in the stomach. Upper intestinal hemorrhage can be successfully treated with splenic artery embolization, followed by splenectomy and gastric resection[35].

To conclude, splenic needle biopsy or core biopsy can be used as an effective diagnostic tool now days to hit the correct histological diagnosis to avoid untoward complications related to disease and treatment in search of accurate pathological diagnosis.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors hereby declare that they have no any conflicts of interests.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: March 14, 2016

First decision: April 20, 2016

Article in press: October 24, 2016

P- Reviewer: Chan EL, Liu QD S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Dasgupta T, Coombes B, Brasfield rd. primary malignant neoplasms of the spleen. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:947–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavanna L, Artioli F, Vallisa D, Di Donato C, Bertè R, Carapezzi C, Foroni R, Del Vecchio C, Lo Monaco B, Prati R. Primary lymphoma of the spleen. Report of a case with diagnosis by fine-needle guided biopsy. Haematologica. 1995;80:241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris NL, Aisenberg AC, Meyer JE, Ellman L, Elman A. Diffuse large cell (histiocytic) lymphoma of the spleen. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of ten cases. Cancer. 1984;54:2460–2467. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841201)54:11<2460::aid-cncr2820541125>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke JS. Surgical pathology of the spleen: an approach to the differential diagnosis of splenic lymphomas and leukemias. Part II. Diseases of the red pulp. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981;5:681–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingle SB, Ingle CR. Splenic lymphoma with massive splenomegaly: Case report with review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:478–481. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gobbi PG, Grignani GE, Pozzetti U, Bertoloni D, Pieresca C, Montagna G, Ascari E. Primary splenic lymphoma: does it exist? Haematologica. 1994;79:286–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healy NA, Conneely JB, Mahon S, O’Riardon C, McAnena OJ. Primary splenic lymphoma presenting with ascites. Rare Tumors. 2011;3:e25. doi: 10.4081/rt.2011.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraemer BB, Osborne BM, Butler JJ. Primary splenic presentation of malignant lymphoma and related disorders. A study of 49 cases. Cancer. 1984;54:1606–1619. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841015)54:8<1606::aid-cncr2820540823>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kehoe J, Straus DJ. Primary lymphoma of the spleen. Clinical features and outcome after splenectomy. Cancer. 1988;62:1433–1438. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881001)62:7<1433::aid-cncr2820620731>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falk S, Stutte HJ. Primary malignant lymphomas of the spleen. A morphologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer. 1990;66:2612–2619. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901215)66:12<2612::aid-cncr2820661225>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmann DL, Kiely JM, Harrison EG, Payne WS. Malignant lymphoma of the spleen. A review of 49 cases in which the diagnosis was made at splenectomy. Cancer. 1966;19:461–469. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196604)19:4<461::aid-cncr2820190402>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KH, Cho CK, Choo SW, Kim HJ, Kim KS. Primary lymphoma of the spleen- a case report. Korean J Surg. 1997;52:912–917. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn JS, Lee S, Chong SY, Min YH, Ko YW. Eight-year experience of malignant lymphoma--survival and prognostic factors. Yonsei Med J. 1997;38:270–284. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1997.38.5.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dachman AH, Buck JL, Krishnan J, Aguilera NS, Buetow PC. Primary non-Hodgkin’s splenic lymphoma. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(98)80061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiros N, Economopoulos T, Christodoulidis C, Dervenoulas J, Papageorgiou E, Mellou S, Styloyiannis S, Tsirigotis P, Raptis SA. Splenectomy in patients with malignant non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2000;64:145–150. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2000.90079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brox A, Bishinsky JI, Berry G. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the spleen. Am J Hematol. 1991;38:95–100. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830380205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izzo L, Binda B, Boschetto A, Carmanico L, Galati G, Fior E, Marini M, Mele LL, Stasolla A. Primary Splenic Lymphoma; the diagnostic and therapeutic value of splenectomy. Haematologica. 2002:87; ECR 20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal SC, Bharucha MA, Deo A, Velling K. Post surgical diagnosis of primary DLBCL presenting as Splenic abscess. Austral - Asian Journal of Cancer. 2012;11:217–220. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konstantiadou I, Mastoraki A, Papanikolaou IS, Sakorafas G, Safioleas M. Surgical approach of primary splenic lymphoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2009;25:120–124. doi: 10.1007/s12288-009-0025-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thanos L, Dailiana T, Papaioannou G, Nikita A, Koutrouvelis H, Kelekis DA. Percutaneous CT-guided drainage of splenic abscess. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:629–632. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.3.1790629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skarin AT, Davey FR, Moloney WC. Lymphosarcoma of the spleen. Results of diagnostic splenectomy in 11 patients. Arch Intern Med. 1971;127:259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.López JI, Del Cura JL, De Larrinoa AF, Gorriño O, Zabala R, Bilbao FJ. Role of ultrasound-guided core biopsy in the evaluation of spleen pathology. APMIS. 2006;114:492–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamb PM, Lund A, Kanagasabay RR, Martin A, Webb JA, Reznek RH. Spleen size: how well do linear ultrasound measurements correlate with three-dimensional CT volume assessments? Br J Radiol. 2002;75:573–577. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.895.750573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peddu P, Shah M, Sidhu PS. Splenic abnormalities: a comparative review of ultrasound, microbubble-enhanced ultrasound and computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:777–792. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iannitto E, Tripodo C. How I diagnose and treat splenic lymphomas. Blood. 2011;117:2585–2595. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-271437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vander Walt JD. Lymphomas in the bone marrow. Diagn Histopathol. 2010;16:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baccarani U, Terrosu G, Donini A, Zaja F, Bresadola F, Baccarani M. Splenectomy in hematology. Current practice and new perspectives. Haematologica. 1999;84:431–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grahn SW, Alvarez J, Kirkwood K. Trends in laparoscopic splenectomy for massive splenomegaly. Arch Surg. 2006;141:755–761; discussion 761-762. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.8.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tam A, Krishnamurthy S, Pillsbury EP, Ensor JE, Gupta S, Murthy R, Ahrar K, Wallace MJ, Hicks ME, Madoff DC. Percutaneous image-guided splenic biopsy in the oncology patient: an audit of 156 consecutive cases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez-Rubio M, López-Cano A, Rendón P, Muñoz-Benvenuty A, Macías M, Garre C, Segura-Cabral JM. Safety and diagnostic accuracy of percutaneous ultrasound-guided biopsy of the spleen: a multicenter study. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009;37:445–450. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armitage JO. How I treat patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2007;110:29–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-041871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tessier DJ, Pierce RA, Brunt LM, Halpin VJ, Eagon JC, Frisella MM, Czerniejewski S, Matthews BD. Laparoscopic splenectomy for splenic masses. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2062–2066. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9748-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu I, Ichikawa N, Yotsumoto M, Sumi M, Ueno M, Kobayashi H. Asian variant of intravascular lymphoma: aspects of diagnosis and the role of rituximab. Intern Med. 2007;46:1381–1386. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kan E, Levy I, Benharroch D. Splenic micronodular T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: effect of prior corticosteroid therapy. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:337–341. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0830-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bird MA, Amjadi D, Behrns KE. Primary splenic lymphoma complicated by hematemesis and gastric erosion. South Med J. 2002;95:941–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]