Abstract

Background:

Psychiatric disorders are common in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We conducted this study to investigate the relationship of IBS and their subtypes with some of psychological factors.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was performed among 4763 staff of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in 2011. Modified ROME III questionnaire and Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire were used to evaluate IBS symptoms. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and 12-item General Health Questionnaire were utilized to assess anxiety, depression and psychological distress. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the association of psychological states and IBS in the total subject and both genders.

Results:

About, 4763 participants with mean age 36/58 ± 8/09 were included the 2106 males and 2657 females. Three thousand and seven hundred and seventy-six (81.2%) and 2650 (57.2%) participants were married and graduated respectively. Subtype analysis of IBS and its relationship with anxiety, depression and distress comparing the two genders can be observed that: IBS and clinically-significant IBS have higher anxiety, depression symptoms, and distress than the subject without IBS (P < 0.001). Women with IBS, have higher scores than men (P < 0.001). Compared to other subtypes, mixed IBS subtype has a higher anxiety, depression, and distress score.

Conclusion:

A high prevalence of anxiety, depression symptoms and distress in our subjects emphasize the importance of the psychological evaluation of the patients with IBS, in order to better management of the patients and may also help to reduce the burden of health care costs.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, distress, irritable bowel syndrome, psychiatric problem

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal (GI) disorder with the absence of organic disease and a number of detrimental effects including; leave of absence, seeking for medical treatment, and a poor quality of life.[1,2] The prevalence of IBS is estimated to be in the range of 2.9–11.4% with variations across contexts and diagnostic criteria.[3,4] One study demonstrated that the prevalence of IBS was about 25% and also claimed that IBS was the second most prevalent GI disorder after gastroesophageal reflux disease in outpatients visiting GI clinics.[5] The syndrome is reported to have a higher prevalence in women than in men, and the age of its onset is in the range of 30–50 years.[3] Four subtypes of IBS were recognized; IBS divided into subgroups according to their stool and defecatory patterns; IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), mixed IBS (IBS-M), and Unsubtyped IBS (IBS-U).

Despite the high prevalence of IBS in general population and the personal and economic costs, its etiologic remains unknown; however, various studies have shown that several factors including abnormal motility of intestine, visceral hypersensitivity, inflammation, neurotransmitter imbalance, disturbance of brain-gut interaction, abnormal central processing, autonomic and hormonal events, and genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors may contribute to incidence of IBS.[6] IBS has strong negative effect on quality of life in patients who suffer from it, and it imposes substantial social and economic costs due to medical seeking behavior and absenteeism.[7,8,9]

Several studies have evaluated the relation between IBS and psychiatric disorders.[10] It has been reported that neurosis, anxiety, depression and dysfunctional cognition are more prevalent in patients with IBS.[11,12,13] In a large randomized controlled trial found that 44% of IBS patients had psychiatric co-morbidity which depressive and anxiety disorders were the most common conditions.[14] Depression in patients with IBS is more severe and prevalent than in healthy individuals.[4] In one study, six major GI features including abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloating, constipation, loss of appetite, and vomiting were considered along with the psychiatric state of the patients. Major depression (13.4%), panic disorder (12.5%) and agoraphobia (17.8%) were found to be more common in patients with two or more GI symptom.[15] A most recent study provided further evidence that GI-specific anxiety is an important mediating factor affecting the GI symptom severity and quality of life in IBS patients.[16]

Most studies have examined the relationship between IBS, as a general term, with psychological factors. However, there is depletion in the relationship with subtypes of IBS and psychological factors in recent studies. Since there is not enough literature on the incidence and natural history and relative factors of a subtype of IBS, efforts should focus on developing well-designed studies to investigate the relationship of IBS and their subtypes with psychological factors and ideally, these studies should be community-based.

The main problems with previous studies are the recruitment of a highly selective group of populations, patient-based studies from health institutions, small sample size, and focus on only limited IBS conditions.

The current study was carried out to record the relationship of IBS and their subtypes with psychological factors in employees of a large university in a central part of Iran and to investigate the relationships between IBS and the psychological states.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

The current study was conducted within part of the Study on the Epidemiology of Psychological Alimentary Health and Nutrition project. This project was a community-based program designed to study the epidemiology of functional GI disorders (FGIDs) in Iran in 2011.[5] Furthermore, the role of different lifestyle, nutritional, and psychological factors in FGIDs symptoms and their severity was investigated. The details of carried out methodology have been explained before.[5]

The project was a cross-sectional study among the staff of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The university had about 20,000 nonacademic employees that working in different centers across Isfahan province. In the current analysis, we used data from 4763 adults who had completed information on personality traits and distress. All of the places (except university teaching hospitals and research centers) were selected as study clusters and subjects were recruited randomly from each cluster. All information was gathered in two separate phases to increase the accuracy of data collection and the response rate. The self-reported questionnaire about psychological factors was applied in the second phase.

Variable assessment

After obtaining written informed consent, data on demographic characteristics, and psychological factors (anxiety, depression, and distress), were collected by standardized self-administered questionnaires.

Demographic factors applied in this study were age, sex as male and female, marital status as unmarried (single, widow, and divorce) and married, educational level as 0–12 years (undergraduate), and >12 years (graduate).

To assess the presence or absence of different symptoms of IBS modified ROME III questionnaire[17,18] and its scoring system. Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaires were used for evaluating the intensity of IBS.[5] Individuals who had IBS symptoms according to ROME III criteria were considered as IBS patient. We defined a group of IBS patient with more frequent symptoms, i.e., those who reported pain or discomfort “often” or “always.” These cases categorized under “clinically-significant IBS” (IBS-S).[17] Subtyping IBS using the predominant stool pattern[19] included: IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-M, and IBS-U.

Distress level was measured by the Iranian validated version of 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). GHQ-12 is a consistent and reliable instrument for using in general population studies. Each item is rated on a four-point scale (less than usual, no more than usual, fairly more than usual, and much more than usual). The system used to score the GHQ-12 questionnaires was the 0-0-1-1 method. Using this method, a participant could have been scored between 0 and 12 points; a score of 4 or more was used to identify a participant with high distress level.[20,21] Cronbach's alpha coefficient has been found to be 0.87.[21]

Anxiety and depression measured by the Iranian validated version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS contains 14 items and consists of two subscales: Anxiety and depression. Each item is rated on a four-point scale, giving maximum scores of 21 for anxiety and depression separately. Scores of 8 or more on either subscale are considered to be a case of psychological morbidity in that area.[22,23] Cronbach's alpha coefficient has been found to be 0.78 for the anxiety subscale and 0.86 for depression sub-scale.[23]

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis of the study population was performed (i.e., mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and frequencies [percentages] for qualitative variables), and differences between groups were analyzed with t-test and Chi-square test.

A binary logistic regression analysis was performed to find the association between anxiety, depression and distress level with IBS (IBS, IBS-S) and its subtypes. The dependent variables were IBS [IBS and clinically-IBS-S][17] and its subtypes [IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-M, and IBS-U] and the independent variables were anxiety, depression, and distress level. Odds ratios (OR) were reported with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

In this study, 4763 participants with mean age 36/58 ± 8/09 were included the 2106 males and 2657 females. Three thousand and seven hundred and seventy-six (81.2%) employers married and 874 (18.8%) subjects were unmarried. One thousand and nine hundred and eighty-six (42.8%) were undergraduate and 2650 (57.2%) subjects were a graduate. Table 1 includes the scoring of anxiety, depression, and distress in IBS and its subtype.

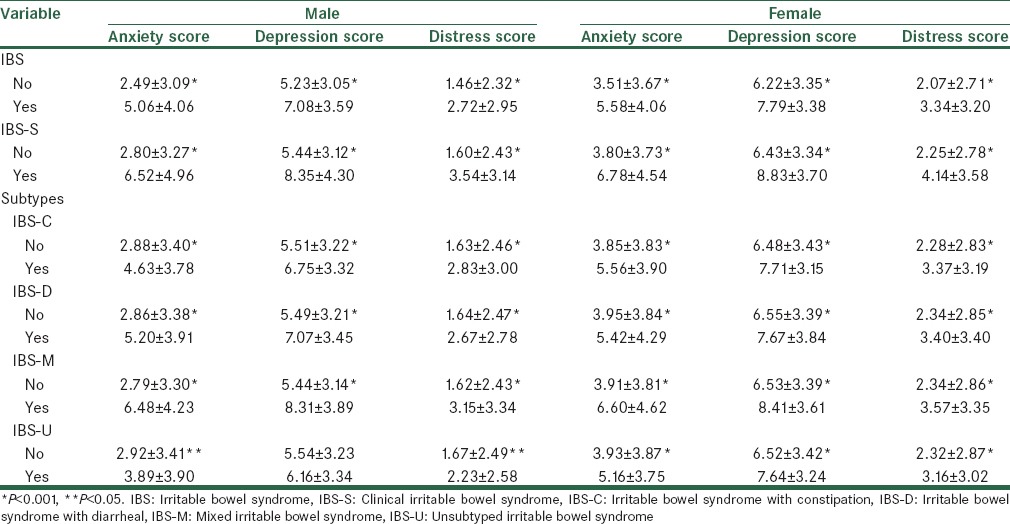

Table 1.

Comparison of anxiety, depression and distress scores in IBS, IBS-S and its subtypes by gender

The subtypes of IBS and its association with anxiety, depression and distress is observed in IBS that anxiety, depression, and distress are significantly higher than the individual without IBS (P < 0.001). Women with IBS have higher scores than males (P < 0.001). The psychiatric problem is more severe in IBS-S [Table 1].

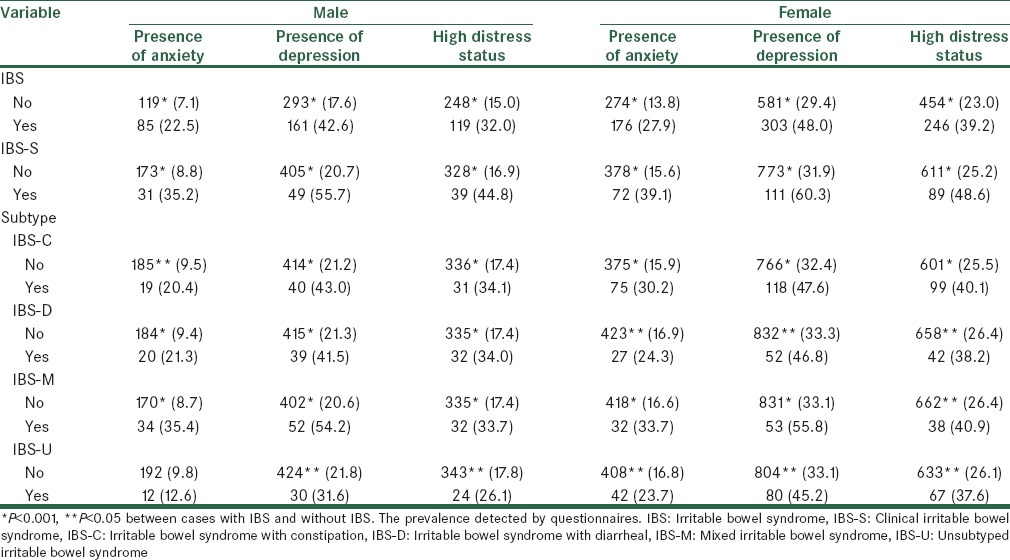

Table 2 shows 1024 employer had IBS within 386 (18.3%) males and 683 (24%) females. 276 individuals had IBS-S within 90 men (4.3%) and 186 women (7%). Among men with IBS-S, 31 (35.2%) people suffering from anxiety, 49 (55.7%) individuals with depression, and 39 (44.8%) employer had psychological distress. Among women, 72 (39.1%) cases of anxiety, and 111 (60.3%) cases of depression, and 89 (48.6%) subjects had psychological distress. Among men with IBS, 85 (22.5%) people had anxiety, 161 (42.6%) depression, and 119 (16.9%) had psychological distress. Among the women, 176 (27.9%) had anxiety, and 303 (48%) had depression, and 246 (39.2) had psychological distress. The levels of significance in Table 2 indicate the percentage differences of anxiety, depression, and high distress among participants with IBS and those without IBS.

Table 2.

Prevalence of anxiety, depression and distress level in IBS, IBS-S and its subtypes by gender

In subtypes, IBS-M had more anxiety, depression, and distress in comparison with other subtypes of IBS. Conversely, IBS-U had lower scores than the other groups.

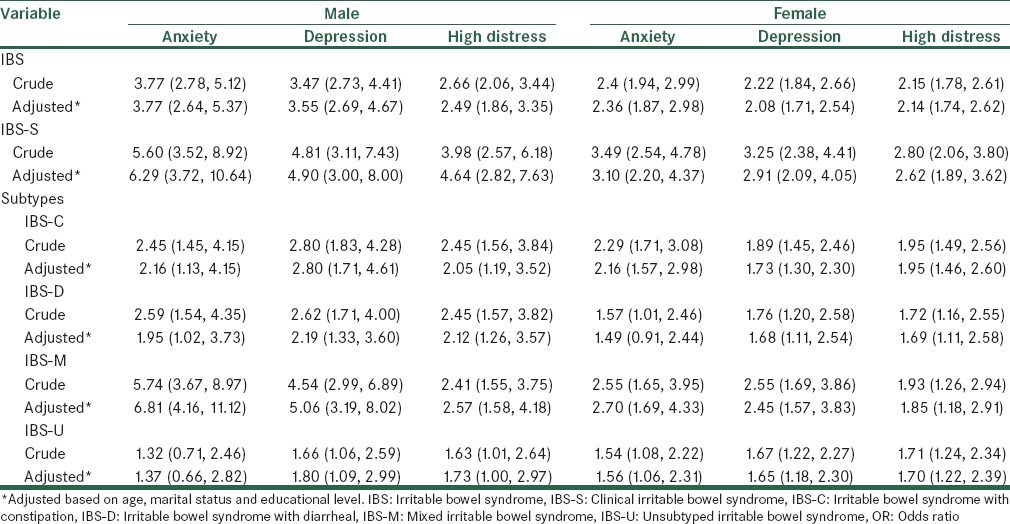

To examine the association of IBS and its subtypes with anxiety, depression, and distress, a multivariate logistic regression was conducted with IBS and its subtypes serving as the dependent variable. The results are shown in Table 3. In crude analysis, anxiety was a risk factor for IBS-S in men with OR, 95% CI: 5.60 (3.52, 8.92) and depression with 4.81 (3.11, 7.43) and distress 3.98 (2.57, 6.18) and in women, anxiety 3.49 (2.54, 4.78), depression 3.25 (2.38, 4.41), and distress 2.80 (2.06, 3.80). In the adjusted model, with affected covariates of demographics characteristics (age, sex, marital status, and educational level) showed sensible changing in OR anxiety and high distress in male with IBS-S. In subtypes, adjusting covariates of demographics characteristics showed sensible changing in OR anxiety in IBS-M.

Table 3.

Curded and adjusted ORs of anxiety, depression, and distress level with IBS, IBS-S and its subtypes by genders

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated whether anxiety and depression and distress occur more frequently in population with IBS; than in healthy subjects. Men with IBS-S are more than 4 times anxiety than in normal individuals, and more than 2 times experience depressive symptoms and distress. It was also observed that women with IBS-S than in normal subjects had more than 2 times of anxiety, depression and distress. This study showed that, the overall prevalence of anxiety, depression symptoms and distress that dedicated by questionnaires in women is higher than men, but the association of psychological disorders in IBS in men more than women. Furthermore, our results support the general hypothesis that subtype of IBS were different on the examined domains; IBS-M individuals had more depression and anxiety and distress than other subtypes of IBS, and was more severe in men. In general, depression, anxiety, and distress scores in IBS-U subtype less than any other subtype.

The high prevalence of anxiety and depression in the local general population (20.8% and 21%, respectively)[24] must be considered as an important factor in the high prevalence of these symptoms in our studied IBS group (24.6% and 45.5%, respectively).

A biopsychosocial model has been suggested to explain the complexity of the pathophysiology of IBS.[3] This includes reciprocal influences and feedback mechanisms between GI changes and psychological factors, and emphasizes the strong relationship between GI symptoms and psychological factors.

Patients with IBS are particularly susceptible to stressful experiences, which produce GI symptoms.[1] Psychiatric disorders are associated with changes in the processing of visceral sensations in patients with IBS, which could elicit the symptoms of IBS. Patients with IBS, who have a concomitant psychiatric diagnosis may also manifest changes in gut-related autonomic nervous system function, affecting gut motility and sensation.[1] In recent years, an appreciation of the modulation of visceral stimuli by the central nervous system has developed, particularly with the growing number of functional neuroimaging studies available.

Anyone with IBS generally has significantly higher psychiatric comorbidity rates than similar groups of general medical patients or patients with organic disorders.[25] The most frequent psychiatric disorder in IBS-S patients is depression, followed by anxiety and somatization disorders. These studies are also aligned with the study conducted by us. As a total, it should be noted that normal population have a higher prevalence of depression.[26]

Based on our study, it seems that IBS subtype was a significant correlate with depression and anxiety, as IBS-M group had the highest scores on depression and anxiety. The reason of high anxiety and depression in mixed groups is not known, but may be due to the simultaneous presence of both diarrhea and constipation digestive problems. In addition, more frequent and nagging symptoms in M-type leading to increase health anxiety, somatic, and social distress. As red flag signs in IBS indicate the need for referral to a gastroenterologist, the high scores on anxiety, depression, and distress, can be seen as a warning sign and reason for referral to gastroenterologists and psychiatric assessment.

From the present study, it seems that IBS-M individuals have a more psychological problem with higher degrees of depression and anxiety but similar distress to other IBS subtypes’. These results varied with was done by Guthrie et al.[14] who documented that high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, and childhood history of sexual abuse in IBS-D patients. Based on our studies, the reason for this difference is not clear but it seems like the sample size of the study was small, and only two type (IBS-C and IBS-D) patients have been examined.

The study from Eriksson and Andre,[27] who investigated the differences in somatic, psychological and biochemical patterns between the subtypes of IBS, showed that IBS-C patients had higher psychological symptoms and higher prolactin values than IBS-D patients. However, the IBS-D group showed dysfunctional body awareness and higher C-peptide values, probably reflecting an altered adrenergic drive. The study concluded that IBS-D patients had the same amount of GI, but less psychological symptoms than IBS-C, suggesting that IBS-D patients differed from the IBS-C group in terms of body awareness, as they were not aware of their dysfunctional state of health, thus coping with preserved quality of life. Moreover, in IBS-D patient's higher levels of C-peptide were found, probably reflecting autonomic nervous system dysfunctions. Several biochemical mechanisms may be involved in the IBS-M type. It seems that, prolactin and C-peptide that are involved in C- and D-type of IBS, both are simultaneous in IBS-M. Furthermore, further biochemical studies are needed to prove the difference between subtypes.

Although etiopathogenetic mechanisms are still not completely clarified, the observed differences in psychopathology between IBS subtypes may be related to alterations of the enteric serotonergic system, as the excess of 5-HT could contribute to diarrhea via 5-HT2B, 3 and 4 receptors,[28] and increased postprandial release of 5-HT in IBS-D patients has been found.[29,30] Conversely, IBS-C subtype may be characterized by an impairment of 5-HT release.[31]

Recently, Zijdenbos et al. suggested that psychological interventions are superior to “care as usual” for improvement of symptoms.[32] In a systematic review and meta-analysis Ford et al. demonstrated a significant benefit of antidepressants over the placebo and psychological therapies over control therapy or a physician's “usual management,” for the treatment of IBS.[33]

A possible limitation of the present study is data are based on a selected group of university staffs and may not be truly representative of the general population. Second different commodity variables could increase the prevalence of mood disorders, more research on wide and complex risk factors such as quality of life, somatization disorders, and sleep quality is needed, and there should be a special focus on the associations between the psychosocial working conditions and IBS. Third, using self-administered questionnaire has some disadvantages such as lack of monitoring and not availability to clarify questions or encourage respondent.

CONCLUSION

A high prevalence of anxiety-depressive symptoms and distress in our subjects, sex, and subtype of IBS had remarkable distributional differences among studied groups, emphasize the importance of the psychological evaluation of the patients with IBS, in order to better management of the patients and may also help to reduce the burden of health care costs.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by Psychosomatic Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Psychosomatic Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences who supported this work and also all staff of IUMS who participated in our study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–31. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Baldassarre G, Altomare DF, Palasciano G. Pan-enteric dysmotility, impaired quality of life and alexithymia in a large group of patients meeting ROME II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2293–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperber AD, Shvartzman P, Friger M, Fich A. A comparative reappraisal of the Rome II and Rome III diagnostic criteria: Are we getting closer to the ‘true’ prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:441–7. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32801140e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han SH, Lee OY, Bae SC, Lee SH, Chang YK, Yang SY, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Korea: Population-based survey using the Rome II criteria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1687–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adibi P, Keshteli AH, Esmaillzadeh A, Afshar H, Roohafza H, Bagherian-Sararoudi R, et al. The study on the epidemiology of psychological, alimentary health and nutrition (SEPAHAN): Overview of methodology. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(Spec 2):S291–S297. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cremonini F, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome: Epidemiology, natural history, health care seeking and emerging risk factors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talley NJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders as a public health problem. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:121–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1736–41. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyrop KA, Palsson OS, Levy RL, Von Korff M, Feld AD, Turner MJ, et al. Costs of health care for irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation, functional diarrhoea and functional abdominal pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:237–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Does psychological distress modulate functional gastrointestinal symptoms and health care seeking? A prospective, community Cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:789–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonsalkorale WM, Perrey C, Pravica V, Whorwell PJ, Hutchinson IV. Interleukin 10 genotypes in irritable bowel syndrome: Evidence for an inflammatory component? Gut. 2003;52:91–3. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budavari AI, Olden KW. Psychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:477–506. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(03)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, Bradley LA, Francisconi C, Drossman DA, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1447–58. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guthrie E, Creed F, Fernandes L, Ratcliffe J, Van Der Jagt J, Martin J, et al. Cluster analysis of symptoms and health seeking behaviour differentiates subgroups of patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:1616–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.11.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yates WR. Gastrointestinal disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams; 2005. pp. 2117–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jerndal P, Ringström G, Agerforz P, Karpefors M, Akkermans LM, Bayati A, et al. Gastrointestinal-specific anxiety: An important factor for severity of GI symptoms and quality of life in IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:646–e179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: New standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9:139–45. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montazeri A, Harirchi AM, Shariati M, Garmaroudi G, Ebadi M, Fateh A. The 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:66. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Ebrahimi M, Jarvandi S. The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noorbala AA, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Yasamy MT, Mohammad K. Mental health survey of the adult population in Iran. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:70–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:765–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammadi MR, Alavi A, Mahmoodi J, Shahrivar Z, Tehranidoost M, Saadat S. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders amongst adolescents in Tehran. Iran J Psychiatry. 2008;3:100–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eriksson EM, Andrexn KI, Eriksson HT, Kurlberg GK. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes differ in body awareness, psychological symptoms and biochemical stress markers. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4889–96. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiller R. Serotonin and GI clinical disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1072–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkinson W, Lockhart S, Whorwell PJ, Keevil B, Houghton LA. Altered 5-hydroxytryptamine signaling in patients with constipation- and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:34–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunlop SP, Coleman NS, Blackshaw E, Perkins AC, Singh G, Marsden CA, et al. Abnormalities of 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:349–57. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiller R. Serotonin, inflammation, and IBS: Fitting the jigsaw together? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:S115–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812e66da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zijdenbos IL, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Quartero AO. Psychological treatments for the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;21:CD006442. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006442.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, Quigley EM, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58:367–78. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]