Abstract

Background:

Central nervous system (CNS) squash cytology (CSC) has established itself as a technically simple, rapid, inexpensive, fairly accurate, and dependable intraoperative diagnostic tool. It helps neurosurgeons immensely when management is dependent on it.

Aims:

This study aimed at finding out the utility of CSC as an intraoperative diagnostic tool from a neurosurgeon's perspective.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty prospectively registered patients with clinical diagnosis of CNS tumors were enrolled in the study. All the patients were subjected to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Intraoperative CSC was performed and smears were stained with Leishman and rapid Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) stain. The diagnosis of CSC was compared with MRI diagnosis and histopathological diagnosis. The CNS tumors were categorized based on clinical and therapeutic implications. Diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value of MRI and CSC were calculated by using appropriate formulae.

Results and Conclusions:

The age range of the CNS tumors included in the study was 2 to 68 years. There was a slight female preponderance. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of preoperative MRI were 90.47%, 82.76%, 79.17%, and 92.31% respectively. These values of utility parameters for CSC were 100% for each of the clinical and therapeutic implications. It helped neurosurgeons in optimizing surgical procedure in 12 cases of meningioma. It influenced surgical management in 1 case of infratentorial pilocytic astrocytoma, and helped in the diagnosis and management of 9 unexpected tumors missed on MRI.

Keywords: CNS squash cytology, CNS tumors, intraoperative diagnosis

Introduction

First introduced in 1930, central nervous system (CNS) squash cytology (CSC) has now been established as a method of intraoperative diagnosis of CNS tumors. The soft consistency of CNS tissue is best suited for squash cytology, which in fact is a hindrance for frozen section. Moreover, ice crystal artifacts may make morphological interpretation of frozen sectioned tissue difficult.[1,2,3,4]

CSC has been accepted by pathologists as technically simple, rapid, inexpensive, fairly accurate, and dependable intraoperative diagnostic tool.[5] It can help neurosurgeon in optimizing surgical procedures and dealing with an unexpected lesion than that determined on clinical and imaging grounds. Thus intraoperative diagnosis by CSC is of utmost importance to neurosurgeons as management is influenced. Role of CSC has increased with the advent of stereotactic biopsies which provide very tiny tissue. Pathologists should train themselves in cytomorphological interpretation of such scanty material. CNS squash smears can help pathologists in this matter. The present study was undertaken to find out the utility of intraoperative squash cytology from a neurosurgeon's perspective.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining clearance from the institutional ethics committee and informed consent, 50 patients with clinical diagnosis of CNS tumors were enrolled in this study. These patients were evaluated clinically for presentation of increased intracranial tension (ICT), localizing signs, and alteration in consciousness status. They were subjected to preoperative imaging by conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Intraoperative CSC was performed and smears were stained with Leishman and rapid Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) stain. The remaining tissue was processed routinely for paraffin sections. The clinical and MRI findings were taken in consideration while interpreting CSC smears. The diagnosis was intimated to neurosurgeons. The diagnosis of CSC was compared with preoperative MRI diagnosis and histopathological diagnosis.

The CNS tumors were categorized based on clinical and therapeutic implications for deciding sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value. In this manner, meningioma, schwannoma, hemangioblastoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, choroid plexus papilloma, and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, which are treated with surgical removal and follow-up, were considered as tumors with benign behavior. Diffuse astrocytoma, glioblastoma, craniopharyngioma, medulloblastoma, central neurocytoma, and metastasis, which are treated with surgical removal combined with chemotherapy or radiotherapy, were considered as tumors with aggressive or malignant behavior.

Each case was discussed with the neurosurgeon to find out how useful the intraoperative diagnosis was on diagnostic and therapeutic grounds. Diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value of MRI and CSC were calculated by using statistical test for diagnostic accuracy test.

Results

The age range of patients with CNS tumors included in the study was 2–68 years. Six tumors (12%) were present in children below 12 years of age. Rest of the tumors were seen in adults. There was a slight female preponderance with 26 females and 24 male patients. There were 6 intraspinal, 30 supratentorial, and 14 infratentorial tumors. The age and site-wise distribution of tumors is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

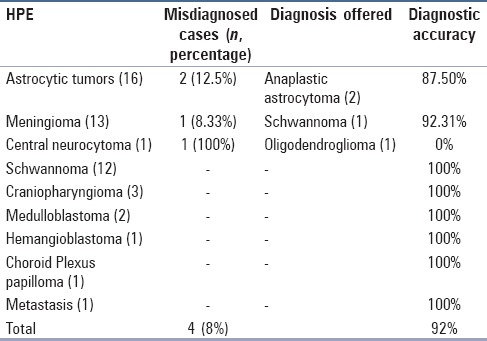

Diagnostic accuracy of central nervous system squash cytology

In children, there were 3 infratentorial tumors with 2 cases of medulloblastoma and 1 case of pilocytic astrocytoma. The supratentorial tumors in children consisted of one case each of glioblastoma, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, and craniopharyngioma. In adults, supratentorial tumors included 11 meningiomas, 7 diffuse astrocytomas, 5 glioblastoma multiformi (GBM), 2 craniopharyngiomas, and 1 case each of choroid plexus papilloma, and central neurocytoma. Infratentorial tumors in adults consisted of 9 schwannomas and 1 case each of meningioma and hemangioblastoma. Three schwannomas, 1 case each of meningioma, diffuse astrocytoma, and metastasis were located in the spine.

Regarding clinical features of these tumors, there was symptomatic overlap. Of various localizing signs, motor deficit was seen in 8 cases, which included 4 spinal, 1 cerebellar, and 3 suprasellar tumors.

Astrocytic tumors, medulloblastomas and choroid plexus papilloma were easy to squash whereas those difficult to squash included meningiomas, schwannomas, craniopharyngiomas, and hemangioblastoma.

Overall diagnostic accuracy of intraoperative CSC is presented in Table 1. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive, value and negative predictive value of preoperative MRI was 90.47%, 82.76%, 79.17%, and 92.31% respectively. These values of utility parameters for intraoperative CSC were 100% for each.

On discussion with the neurosurgeon, intraoperative CSC helped the neurosurgeon in optimizing surgical procedure in 12 out of 13 correctly diagnosed meningioma cases. In infratentorial tumors, surgical management was influenced in 1 case of pilocytic astrocytoma, which was removed along with cyst wall and in 1 case of hemangioblastoma, where the cyst wall was left alone. Intraoperative cytology also helped in the diagnosis and management of 9 unexpected lesions, which were missed on MRI. We have not attempted grading of tumors, and assessment of margins was not demanded in any of our cases of GBM.

Discussion

The overall inability to easily access the cranial cavity contents makes diagnosis and management of CNS tumors difficult than that of other visceral tumors. The advances in neuroimaging have revolutionized the management of such tumors in terms of their diagnosis and treatment. The knowledge of location, clinical presentation, and imaging findings, as well as its correlation with cytological and histological findings is of utmost importance to pathologists. Consideration of clinical presentation, exact location of the lesion being examined, common locations of such tumors, and correlation with radioimaging findings provides reasonably accurate cytological or histological diagnosis in CNS tumors. Moreover, this methodology allows reasonable and realistic differential diagnosis.[6,7]

The advent of stereotactic biopsy or endoscopic approach has made it possible to approach inaccessible lesions. These approaches have increased the responsibility of pathologist who has to play an important role in its evaluation, diagnosis, and management.[6]

The role of intraoperative diagnosis in CNS tumors need not be overemphasized. It can achieve targeting of lesion and provide guidance to the neurosurgeon in modifying and monitoring the surgical approach. It also helps in assessing the margins in obtaining the biopsy or ascertaining the adequacy of stereotactic biopsies as well as in collecting the samples for investigations such as culture.[3,8,9] The choice of method for intraoperative diagnosis depends upon the availability of technology, the type of neurosurgical procedure being carried out (craniotomy or stereotactic biopsy), and the availability of the amount of tissue available thereupon. In case of craniotomy, wherein ample amount of tissue may be available, intraoperative diagnosis can be obtained by frozen sections and squash or smear cytology in combination. However, in case of stereotactic biopsies, a tiny tissue is provided which might necessitate cytological method (squash or imprint).[6]

Frozen section and squash or imprint cytology are complimentary to each other, and when both are available and diagnosis is mismatched, frozen section has an upper hand in final intraoperative diagnosis. Each case, however, needs to be dealt and evaluated on its own merit.[3,8,10] Both these procedures have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Distinct advantage of frozen section lies in its ability to provide both fairly good cytomorphological details and finer histological typing if there is no limitation of tissue availability for diagnosis.[10] However, frozen section procedure needs costly equipments and continuous electric supply. This can be of considerable concern in developing countries such as India.[5,11] In addition, this procedure is technically demanding.[11] The overall soft nature of CNS tissue and CNS tumors is not best suited for frozen sections.[3,4,8,11] In addition, frozen section is faced with ice crystal formation particularly in astrocytomas and the freezing artifacts cause distortion of architecture.[4,5,8] While frozen section is useful for intraoperative diagnosis of more firm CNS tumors such as meningiomas and ependymomas, the distinct advantage of CNS squash smears in intraoperative diagnosis is the ease with which soft CNS tumors can be crushed to obtain a good cellular smear.[3,4,5,8,11]

CSC assures safe handling of tissues by avoiding the use of cryostat machine, which is likely to be contaminated by slow virus disease in the process of frozen section in a pertinent case.[3,8,9]

Accuracy of a cytological diagnosis heavily depends on the consistency of a tissue. The soft and friable tissues obviously are easy to smear and yield good cellularity. This is exhibited by CNS tumors such as gliomas, pituitary adenomas, medulloblastomas, and metastatic carcinomas.[5] We wholeheartedly share this experience. Another advantage of CNS cytology, such as squash cytology, is that it can be done on a tiny tissue, and is of great value when the tissue obtained is limited or one does not want to lose it to frozen section but preserve it for paraffin sections. The CSC not only economizes on tissue but also on time. The intraoperative diagnosis with it can be obtained in as early as 10 min.[9,11,12,13,14] The rapid H and E and Leishman stains used in the present study took 10 min for staining and another few minutes for evaluation.

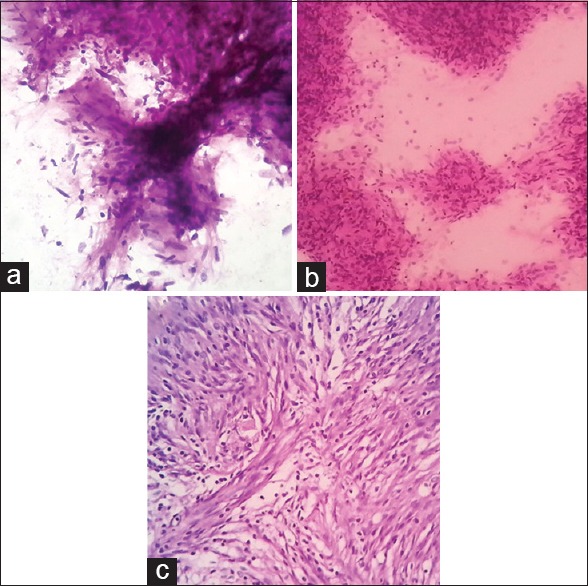

Squash smear cytology provides good cellular details and is far better for appreciating intercellular matrix tissue, inflammatory cells, lymphoma cells, or cells of pituitary adenoma, which are loosely arranged.[4,10,13] As seen in the present study, the architecture and details of tumor cells are well-maintained in the cases of choroid plexus papilloma. Similarly, cellular areas of schwannoma and whorls of meningioma [Figure 1a and b] are also well-appreciated in squash smear cytology.[11] In the present study, papillae were better appreciated with H and E and Leishman stains. Whorls were better appreciated with H and E stain. We also found H and E stain to be best suited for appreciation of fibrillary background. In our air-dried smears, which were subsequently stained with Leishman stain, the cells looked flat and larger than wet-fixed smears. We were more comfortable with wet-fixed smears stained with H and E stain than with air dried smears stained with Leishman stain. Moreover, it was easy to compare the results of wet-fixed H and E stained smears with subsequent paraffin sections [Figure 1b and c].

Figure 1.

(a) Central nervous system (CNS) squash cytology of schwannoma (H&E stain, ×400); (b) CNS squash cytology [showing whorls of meningioma] of meningioma (H&E stain, ×400); (c) Histopathology of meningioma (H&E stain, ×400)

Although CNS squash smears provide fairly good cytological details and suggest few histological patterns, there are many diagnostic difficulties.[8] This is exemplified in underdiagnosing two cases of GBM as anaplastic astrocytoma. This can be attributed to sampling error resulting in obviation of characteristic necrosis which is important for diagnosis of GBM. Alternatively, it may be due to the fact that necrosis cannot be recognized because it sticks poorly to the slides.[8] The necrosis can also be missed on frozen section, as reported by Mitra et al.,[5] we misdiagnosed one case of meningioma at parietal location as schwannoma. This diagnosis was based on spindle cell morphology and was offered even in the absence of characteristic cellular Antony A areas. The experience is shared by Mitra et al.[5] In this case smears lacked epithelial whorls characteristics of meningioma.[8] We must confess that we failed to consider the fact that parietal location is not a site for schwannoma. We missed a case of central neurocytoma by misdiagnosing it as oligodendroglioma. Both these tumors have similar cytomorphological features with presence of monotonous round nuclei having slightly dense but bland chromatin. Many of these may be devoid of cytoplasm. Perinuclear halo characteristic of oligodendroglioma on histological preparation is a fixation artifact. It is not seen in cytological preparation. One may sometimes detect calcification in smear which facilitates the diagnosis of oligodendroglioma. Presence of mini-gemistocytes, sparse glial fibers, and perineuronal satellitosis also favor its diagnosis. On the other hand, foci or background of finely fibrillary neuropil is a feature characteristic of neurocytoma.[8] We failed to differentiate these nuances, but moreover, we disregarded the central location of this tumor which should have clinched the diagnosis in the given setting of cytomorphology. Similar experience is shared by Savargaonkar.[9] Twice we disregarded the location of tumor thereby offering wrong diagnosis. This experience emphasizes the fact that intraoperative diagnosis is a very crucial exercise which needs to be dealt with extreme care and in correlation with clinical and radioimaging findings. The only solace was that none of these misdiagnoses had a deleterious impact on patient management.

Importance of the investigation of intercellular matrix in the cytological evaluation of CNS tumors needs special mention. The squash smears can highlight the intercellular matrix in the form of astrocytic fibers and neuropil. The importance of neuropil has been dealt with while discussing differentiation of oligodendroglioma from neurocytoma. The well demonstrated course and intricately woven fibrillary background in appropriate cytological setting favors the diagnosis of astrocytoma over that of reactive astrocytosis, which is a very close differential diagnosis of low grade astrocytoma. In reactive astrocytosis, one sees very long robust processes which do not display networking, along with evenly spaced astrocytes.[8] Incidentally, we have not come across a case of reactive astrocytosis in our material.

In the present study, the intraoperative diagnosis was sought on craniotomy specimens. However, with the advent of stereotactic biopsy which provides an excellent opportunity to access deep-seated CNS lesions, pathologist will have to equip themselves in evaluating very tiny tissues. They will also have to train themselves in relying entirely on cytological features for definitive diagnosis. In CNS stereotactic biopsies, a very limited tissue is available for evaluation and CNS cytology is the best method for checking the adequacy of the procedure.[3] Practicing CNS squash smears in intraoperative diagnosis in open biopsies or craniotomy procedure will provide this opportunity.[5,6,8,11,12,13,14]

The primary aim of this study was to assess the degree to which our intraoperative diagnosis with squash cytology helped the neurosurgeon in management of the patients. This was achieved by discussing each case on its own merit with the neurosurgeon. Our consultation was of help in cases of meningioma, pilocytic astrocytoma, and hemangioblastoma, as well as in tumors where the preoperative MRI diagnosis was not offered or was proved to be wrong. Similarly, neurosurgeons were keen to know intraoperative diagnosis in cases of suprasellar tumors for the obvious fear of causing neurological deficit with overzealous tissue loss.

We relied on classification based on therapeutic measures for categorizing CNS tumors in two groups for calculation of utility parameters such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values. Jaiswal et al. have expressed similar views.[11] Our experience of getting nonspecific or wrong diagnosis in some cases with preoperative imaging is shared by authors such as Mitra et al.[5]

The diagnostic accuracy of CNS squash smear was 92% with 4 misdiagnosed cases. However, because these misdiagnosed cases belonged to the same category of therapeutic measures, the predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity was not compromised. The diagnostic accuracy of the whole sample and of different tumors in our study was comparable with other studies.[5,7,9]

The present study emphasizes the importance of CNS squash smear as a rapid, reliable, and cost-effective method for intraoperative diagnosis. Similar to other authors, it also emphasizes the importance of clinical and imaging correlation and establishing rapport with neurosurgeon for understanding and improving the diagnostic skills.[3,7]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Eisenhardt L, Cushing H. Diagnosis of intracranial tumors by supravital technique. Am J Pathol. 1930;6:541–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma N, MisraV, Singh PA, Gupta SK, Dabnath S, Nautiya A. Comparative efficacy of imprint and squash cytology in diagnostic lesions of the central nervous system. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1693–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ud Din N, Memon A, Idress R, Ahmad Z, Hasan S. Central nervous system lesions: Correlation of intra operative and final diagnoses, six year experience at a referral centre in a Developing Country, Pakistan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1435–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha B, Patel V, Patel K, Agarwal A. Role of squash smear technique in intra operative diagnosis of CNS tumors. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2013;2:889–92. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitra S, Kumar M, Sharma V, Mukhopadhyay D. Squash preparation: A reliable diagnostic tool in the intra operative diagnosis of central nervous system tumors. J Cytol. 2010;27:81–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.71870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell SZ. Intraoperative consultation, cytologic preparations, and frozen section in the central nervous system. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1635–52. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1635-ICCPAF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goel D, Sundaram C, Paul TR, Uppin SG, Prayaga AK, Panigrahi MK, et al. Intraoperative cytology(squash smear) in neurosurgical practice- pitfalls in diagnosis experience based on 3057 samples from a single institution. Cytopathology. 2007;18:300–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma S, Deb P. Intraoperative neurocytology of primary central nervous system neoplasia: A simplified and practical diagnostic approach. J Cytol. 2011;28:147–58. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.86339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savargaonkar P, Farmer PM. Utility of intra-operative consultations for the diagnosis of central nervous system lesions. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2001;31:133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma S K, Kumar R, Srivani J, Arnold J. Diagnostic accuracy of squash preparations in central nervous system tumors. Iran J Pathol. 2013;8:227–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaiswal S, Vij M, Jaiswal AK, Behari S. Intraoperative squash cytology of central nervous system lesions: A single center study of 326 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:104–12. doi: 10.1002/dc.21506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malhotra V, Puri H, Bajaj P. Comparison of smear cytology with histopathology of the CT guided stereotactic brain biopsy. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2007;50:862–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nigam K, Nigam N, Mishra A, Nigam N, Narang A. Diagnostic accuracy of squash smear technique in brain tumors. JARBS. 2013;5:186–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah AB, Muzumdar GA, Chitale AR, Bhagwati SN. Squash preparation and frozen section in intraoperative diagnosis of central nervous system tumors. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:1149–54. doi: 10.1159/000332104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]